Difference between revisions of "Palestine" - New World Encyclopedia

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) m |

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 241: | Line 241: | ||

The British government conducted an inquiry and issued the Passfield White Paper, in October 1930, which called for a halt to Jewish immigration, recommended that land be sold only to landless Arabs, and that the question of “economic absorptive capacity” be based on levels of Arab and Jewish unemployment. Palestinian Jews and London Zionists protested, and in February 1931, the British prime minister, [[Ramsay MacDonald]], wrote to Chaim Weizmann nullifying the Passfield White Paper. Arabs saw that recommendations made in Palestine could be annulled by Zionist influence at in London, so in December 1931, a Muslim congress in Jerusalem attended by delegates from 22 countries warned against the danger of Zionism. | The British government conducted an inquiry and issued the Passfield White Paper, in October 1930, which called for a halt to Jewish immigration, recommended that land be sold only to landless Arabs, and that the question of “economic absorptive capacity” be based on levels of Arab and Jewish unemployment. Palestinian Jews and London Zionists protested, and in February 1931, the British prime minister, [[Ramsay MacDonald]], wrote to Chaim Weizmann nullifying the Passfield White Paper. Arabs saw that recommendations made in Palestine could be annulled by Zionist influence at in London, so in December 1931, a Muslim congress in Jerusalem attended by delegates from 22 countries warned against the danger of Zionism. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Arab rebellion==== | ||

| + | The Nazi rise to power in Germany in 1933 and persecution of Jews throughout Europe increased Jewish immigration, which rose to 30,000 in 1933, 42,000 in 1934, and 61,000 in 1935, provoking acts of violence against Jews and the British in 1933 and 1935. The Arab population of Palestine also grew rapidly. A further Arab demand to end Jewish immigration cease, prohibit land transfer, and establish democratic institutions be established led nowhere. Rising nationalism in Egypt and Syria, increasing unemployment in Palestine, and a poor citrus harvest, touched off an Arab revolt, from 1936-39. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In April 1936, two Jews were murdered, violence escalated, and Arab groups started a general strike in Jaffa and Nabulus. The Jerusalem mufti presided over an Arab high committee, that repeated demands for the end of Jewish immigration and land sales, and independence, as well as calling for a general strike, a tax revolt, and closure of government offices. Meanwhile, Arab rebels and volunteers from other countries attacked Jewish settlements. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A British inquiry, the Peel Commission, in July 1937, declared the mandate unworkable, recommended that the region be partitioned, recommended an area much greater than existing Jewish land holdings, and advocated the transfer by force of the Arab population. Horrified, Arabs escalated the revolt, until In September 1937 the British declared martial law. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The revolt left more than 5000 Arabs dead, 15,000 wounded, and 5600 were imprisoned. The general strike encouraged Zionist self-reliance, the revolt united Jewish settlers behind Ben-Gurion, and the Haganah were given permission to arm itself. Traditional Arab leaders were either killed, arrested, or deported, leaving a dispirited, disarmed and divided Arab population. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A subsequent Woodhead Commission report In November 1938 recommended against the Peel Commission's plan and put forward an alternative which drastically reduced the area of the Jewish state and limited the sovereignty of the proposed states. In May 1939, the British government White Paper said that the Jewish national home should be established within an independent Palestinian state, and that Jewish immigration would be limited to 75,000 during the next five years, after which Jewish immigration would be subject to Arab agreement. Both Arabs and Zionists rejected the White Paper, which marked the end of cordial relations between Zionism and the British government. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By 1940, the number of rural Zionist colonies had increased to about 200, Jewish landholdings had risen to 383,500 acres, or one-seventh of the cultivatable land, the Jewish population had reached 467,000, about one-third of a total population of about 1,528,000, and [[Tel Aviv]] was an all-Jewish city of 150,000 inhabitants. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===World War II=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Selection Birkenau ramp.jpg|left|thumb|300px|"Selection" on the ''Judenrampe'', [[Auschwitz concentration camp|Auschwitz]], May/June 1944. To be sent to the right meant slave labor; to the left, the [[gas chamber]]s. This image shows the arrival of Hungarian Jews from [[Carpathian Ruthenia|Carpatho-Ruthenia]], many of them from the [[Berehove|Berehov]] ghetto. It was taken by Ernst Hofmann or Bernhard Walter of the SS. Courtesy of [[Yad Vashem]].<ref name=AuschwitzAlbum>[http://www1.yadvashem.org/exhibitions/album_auschwitz/home_auschwitz_album.html "The Auschwitz Album"], [[Yad Vashem]].</ref>]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Holocaust123.JPG|thumb|300px|right|Corpses in Auschwitz; from [[Yad Vashem]].]] | ||

| + | Between 1939 and 1945 German Nazis killed more than six million Jews in the [[Holocaust]], a horror that gave new impetus to the movement to form a Jewish state. British attempts to prevent Jewish immigration to Palestine in the face of the Holocaust led to the disastrous sinking of two ships carrying Jewishh refugees — the Patria (November 1940) and the Struma (February 1942). In response, the Irgun, led by Menachem Begin, and LEHI (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel), also known as the Stern Gang, launched attacks on the British, culminating in the murder of Lord Moyne, a British minister of state, in Cairo in November 1944. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Arabs in Palestine remained quiet throughout the war. Amin al-Husseini had fled to Germany, from where he tried to rally Arabs in support of the Axis powers against Britain and Zionism. Most supported the Allies— approximately 23,000 Arabs enlisted in the British forces, as did 27,000 Jews. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In August 1945, U.S. President Harry S Truman asked British Prime Minister Clement Attlee to allow 100,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors into Palestine. In October 1944, Arab heads of state issued the Alexandria Protocol, which said that although they regretted the bitter fate inflicted upon European Jewry, solving the problem of European Jewry should not be achieved by inflicting injustice on Palestinian Arabs. The Arab League, formed in March 1945, appointed an Arab Higher Executive for Palestine (the Arab Higher Committee), and later declared a boycott of Zionist goods. | ||

xxx | xxx | ||

Revision as of 07:59, 4 August 2007

- This article is about the geographical area known as Palestine. For other uses of the term, see Palestine (disambiguation).

Palestine (from Latin: Palaestina; Hebrew: ארץ־ישראל Eretz-Yisra'el, formerly also פלשתינה Palestina; Arabic: فلسطين Filasṭīn, Falasṭīn, Filisṭīn) is one of several names for the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River and various adjoining lands.

Different geographic definitions of Palestine have been used over the millennia, and these definitions themselves are politically contentious. In recent times, the broadest definition of Palestine has been that adopted by the British Mandate, and the narrowest is that used in contemporary politics today, called the Palestinian territories, which are the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Other English names for this region include: Canaan, Land of Israel, and Holy Land.

Part of the region is known as the Holy Land and is held sacred among Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Since the early twentieth century it has been subject to conflicting claims of Jewish and Arab national movements, leading to on-going violence.

Etymology

The term "Palestine" derives from the word Philistia, the name given by Greek writers to the land of the Philistines, who in the twelfth century B.C.E. occupied land between modern Tel Aviv and Gaza. The word in Hebrew is פְּלְשְׁתִּים Pelishtim, this word is derived from the word פְּלִישָׁה Pelisha, meaning invasion or incursion.

During the Roman period, the Iudaea Province (including Samaria) covered most of Israel and the Palestinian territories. But following the Bar Kokhba rebellion in the second century, as part of a program of cooptation and forced migration, the Romans tried to erase the Jewish connection to the land of Judea, renaming it Syria Palaestina. The name made its way thence into Arabic, where it has been used to describe the region at least since the early Islamic era.

Geography

The name Palestine has long been used as a general term for a region without precise boundaries. The eastern boundary has been especially imprecise, although frequently regarded as east of the Jordan River, sometime extending to the edge of the Arabian desert. The northern border is between modern Israel and Lebanon, to the west is the Mediterranean Sea, and the south, the Negev, sometimes reaching the Gulf of Aqaba.

History

Human remains found south of Lake Tiberias date back as early as 600,000 B.C.E. The discovery of the "Palestine Man" in the Zuttiyeh Cave in Wadi Al-Amud near Safad in 1925 provided some clues to human development in the area. In the caves of Shuqba in Ramallah and Wadi Khareitun in Bethlehem, stone, wood and animal bone tools were found and attributed to the Natufian culture (12,500 B.C.E. – 10,200 B.C.E.). The Natufians lived in caves, as did their Paleolithic predecessors, and it is possible that they were experimenting in agriculture. Other remains from this era have been found at Tel Abu Hureura, Ein Mallaha, Beidha and Jericho. People between 10,000 B.C.E. and 5000 B.C.E., gradually domesticated animals, cultivated crops, produced pottery, and built towns. Evidence of such settlements were found at Tell es-Sultan, Jericho and include mud-brick rounded and square dwellings, pottery shards, and fragments of woven fabrics.

Ghassulians

The Ghassulian period was an archaeological stage dating to the Middle Chalcolithic Period (Copper Age) in southern Palestine (c. 3800 – 3350 B.C.E.). They are so named because the pottery and flints characterising their settlements were noticed in the excavations of Tulaylat al-Ghassul in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea in modern Jordan in the 1930s. People from this era lived in small hamlet settlements, and migrated southwards from Syria into Palestine. Houses were trapezoid-shaped and built mud-brick, covered with remarkable wall paintings. Their pottery was highly elaborate, including footed bowls and horn-shaped drinking goblets, indicating the cultivation of wine. They buried their dead in stone dolmens. At Beersheba there was a copper-working industry, and also evidence of an ivory-working industry. The Ghassulian phase led to the Canaanite civilization, the economy of which produced fruit and vegetables, grains and cereals, had transhumance and nomadic pastoral systems of animal husbandry, and commercial production of wine and olives.

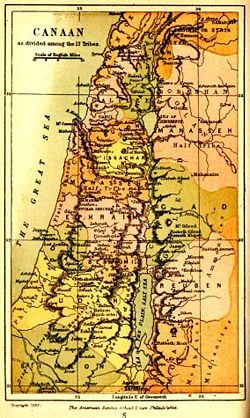

Canaanite city states

The Canaanites were a smaller ethnic group radiating out of modern day Lebanon, who are mentioned in the Bible and Ancient Egyptian texts, and who are only one among many ethnic groups in this area. Most of these ethnic groups assimilated to the same wider culture and are sometimes difficult to distinguish from each other.

By the early Bronze Age (3000 - 2200 B.C.E.) independent Canaanite city-states were established in plains and coastal regions and surrounded by mud-brick defensive walls, and most of these cities relied on nearby agricultural hamlets for food needs. These city-states held trade and diplomatic relations with Egypt and Syria. Parts of the Canaanite urban civilization were destroyed around 2300 B.C.E., though there is no consensus as to why.

In the Middle Bronze Age (2200 - 1500 B.C.E.), Canaan was influenced by the surrounding civilizations of Egpyt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, and Syria. Nomads, came probably from east of the Jordan River, and included the Amorites from the Syrian Desert, who lived in the hill country, as opposed to the Canaanites who lived in the plains and on the coast—areas favourable to agriculture. Diverse commercial ties and an agriculturally based economy led to the development of new pottery forms, the cultivation of grapes, and the extensive use of bronze. Burial customs from this time seemed to be influenced by a belief in the afterlife.

Egyptian conquest

Political, commercial and military events during the Late Bronze Age period (1450 - 1350 B.C.E.) were recorded by ambassadors and Canaanite proxy rulers for Egypt in several hundred cuneiform documents known as the Amarna Letters. Shortly before the death of Ahmose I (1514 B.C.E.), Egyptian armies began to conquer Palestine. The land Syria-Palestine, known to Egyptians as Retenu, was divided into three administrative districts, each under an Egyptian governor. The third district, Canaan, included all of Palestine from the Egyptian border to Byblos. About 1292 B.C.E., the increasingly weak rule of the last pharaohs of the eighteenth dynasty was replaced by the strong arm of the second and third kings of the nineteenth dynasty, Seti I and Rameses II (1279–13 B.C.E.), who consolidated the crumbling Egyptian empire.

Philistines

The historic Philistines (Hebrew פְּלְשְׁתִּים, plishtim; Arabic: فلسطين Filasṭīn, Falasṭīn) were a people who invaded the southern coast of Canaan around the time of the arrival of the Israelites, about 1250 B.C.E., their territory being named Philistia in later contexts. Their origin has been debated among scholars, but modern archaeology has suggested early cultural links with the Mycenean world in mainland Greece.

The Philistines occupied the five cities of Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath, along the coastal strip of southwestern Canaan, that belonged to Egypt up to the closing days of the Nineteenth Dynasty (ended 1185 B.C.E.). The biblical stories of Samson, Samuel, Saul and David include accounts of Philistine-Israelite conflicts. The Philistines long held a monopoly on iron smithing (a skill they possibly acquired during conquests in Anatolia), and the biblical description of Goliath's armor is consistent with this iron-smithing technology.

There was almost perpetual war between the Philistines and Hebrews. They sometimes held the Hebrews, especially the southern tribes, in servitude; at other times they were defeated with great slaughter. According to the Bible, the Philistine cities were ruled by seranim (סְרָנִים, "lords") who acted together for the common good. After their defeat by the Hebrew king David, who originally for a time worked as a mercenary for Achish of Gath, kings replaced the seranim, governing from various cities. Some of these kings were called Abimelech, which was initially a name and later a dynastic title.

Pottery remains found in Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gat, Ekron and Gaza decorated with stylized birds provided the first archaeological evidence for Philistine settlement in the region. The Philistines are credited with introducing iron weapons and chariots, as well as new ways to ferment wine.

Hebrews arrive

Though there is a debate over whether the Hebrews arrived to Canaan from Egypt, or emerged from among the local population existent there at the time, these events are generally dated to between the thirteenth and twelfth centuries B.C.E.

From about the time the Philistines settled, the entire Middle East fell into a "Dark Age" from which it took centuries to recover. The Biblical book of Genesis relates how some of the descendents of Israel became Egyptian slaves. Some Bible commentaries place the birth of Moses around 1300 B.C.E. The Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, led by Moses, and its chronology are much-debated. Some believe that the Exodus took place in the reign of Ramesses II (1279 B.C.E. to 1213 B.C.E.) due to the Egyptian cities named in Exodus (Pithom and Rameses). Evidence for an Israelite presence in Palestine has been found from only six years after the end of the reign of Rameses II, in the Merneptah Stele, documenting military campaigns in Canaan.

The demands of foreign bureaucrats, combined with internal decay, had weakened the Canaanite vassal princes of Palestine. In their initial attacks under Joshua, the Hebrews occupied most of Canaan, which they settled according to traditional family lines derived from the sons of Jacob and Joseph (the "tribes" of Israel). No formal government existed and ad hoc leaders, or the "judges" of the biblical Book of Judges, led in times of crisis. Around 1140 B.C.E., the Canaanite tribes tried to destroy the Israelite tribes of northern and central Canaan, but were defeated.

United kingdom

Wealth returned to the region by the end of the period from the collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and Syria, and the Egyptian Empire in Syria and Palestine, between 1206 and 1150 B.C.E., to the rise of settled Aramaean kingdoms of the mid tenth century B.C.E., and the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Friction between Philistines and Israelites over trade caused the Israelites to unite under one king around 1050 B.C.E. Samuel, one of the last of the judges, anointed Saul ben Kish from the tribe of Benjamin as king. In 1000 B.C.E., Jerusalem made the capital of King David's kingdom and it is believed that the First Temple was constructed in this period by King Solomon. By 930 B.C.E. the kingdom was split into two kingdoms: the northern Kingdom of Israel, and the southern Kingdom of Judah.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the late thirteenth, the twelfth and the early eleventh centuries B.C.E. witnessed the foundation of perhaps hundreds of insignificant, unprotected village settlements, many in the mountains of Palestine. From around the eleventh century B.C.E., there was a reduction in the number of villages, though this was counterbalanced by the rise of certain settlements to the status of fortified townships.

Assyrians and Babylonians

Between 722 and 720 B.C.E., the northern kingdom of Israel was destroyed by the Assyrian Empire and the Hebrew tribes - thereafter known as the (Lost Tribes) - were exiled. In 586 B.C.E., Judah was conquered by the Babylonian Empire and Jerusalem and the First Temple were destroyed. Most of the remaining Hebrews, and much of the other local population, were sent into slavery in Babylonia.

Persian rule

Cyrus II of Persia conquered the Babylonian Empire by 539 B.C.E. and incorporated Judah and Palestine into the Persian Empire. Cyrus organized the empire into provincial administrations called satrapies. The administrators of these provinces, called satraps, had considerable independence from the emperor. The Persians allowed Jews to return to the regions that the Babylonians had exiled them from.

The exiled Jews who returned to the lands they had occupied encountered the Jews that had remained, surrounded by a much larger non-Jewish majority. One group of note (that exists up until this day) were the Samaritans, who adhered to most features of the Jewish rite and claimed to be descendants of the Assyrian Jews. They were not recognized as Jews by the returning exiles for various reasons (at least some of which seem to be political). The return of the exiles from Babylon reinforced the Jewish population, which gradually became more dominant and expanded significantly. Tt was during this period that the Second Temple in Jerusalem was built.

Sabastiye, near Nablus, was the northernmost province of the Persian administration in Palestine, and its southern borders were drawn at Hebron. Some of the local population served as soldiers and lay people in the Persian administration, while others continued to agriculture. In 400 B.C.E., the Nabataeans made inroads into southern Palestine and built a separate civilization in the Negev that lasted until 160 B.C.E.

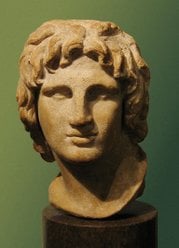

Hellenistic rule

The Persian Empire soon fell under the Greek forces of the Macedonian general Alexander the Great. . After his death, with the absence of heirs, his conquests were divided amongst his generals, while the region of the Jews ("Judah" or Judea as it became known) was first part of the Ptolemaic dynasty and then part of the Seleucid Empire. There were over 30 kings of the Seleucid dynasty from 323 B.C.E. to 60 B.C.E. At its greatest extent, the Empire comprised central Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, Turkmenistan, Pamir and the Indus valley.

The landscape during this period was markedly changed by extensive growth and development that included urban planning and the establishment of well-built fortified cities. Hellenistic pottery was produced that absorbed Philistine traditions. Trade and commerce flourished, particularly in the most Hellenized areas, such as Askalan, Gaza, Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Nablus (Sabastiya, Tel Balata and Jabal Jizrim).

The Jewish population in Judea was allowed limited autonomy in religion and administration. In the second century B.C.E. fascination in Jerusalem for Greek culture resulted in a movement to break down the separation of Jew and Gentile and some people even tried to disguise the marks of their circumcision. Disputes between the leaders of the reform movement, Jason and Menelaus, eventually led to civil war and the intervention of Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

Maccabean revolt

In 167 B.C.E., after Antiochus issued decrees in Judea forbidding Jewish religious practice, a rural Jewish priest, Mattathias the Hasmonean, sparked the revolt against the Seleucid empire by refusing to worship the Greek gods. Mattathias slew a Hellenistic Jew who stepped forward to offer a sacrifice to an idol in Mattathias' place. He and his five sons fled to the wilderness of Judea. After Mattathias' death about one year later, his son Judah Maccabee led an army of Jewish dissidents to victory over the Seleucid dynasty.

The revolt itself involved many individual battles, in which the Maccabean forces gained infamy among the Syrian army for their use of guerrilla tactics. After the victory, the Maccabees entered Jerusalem in triumph and ritually cleansed the Temple, re-establishing traditional Jewish worship there and installing Jonathan Maccabee as high priest. A large Syrian army was sent to quash the revolt, but returned to Syria on the death of Antiochus IV. Its commander Lysias, preoccupied with internal Syrian affairs, agreed to a political compromise that provided religious freedom.

Following the re-dedication of the temple, the supporters of the Maccabees were divided over the question of whether to continue fighting. Those who sought the continuation of the war of national identity were led by Judah Maccabee. On his death in battle in 160 B.C.E., Judah was succeeded as army commander by his younger brother, Jonathan, who was already High Priest. Every year Jews celebrate Hanukkah in commemoration of Judah Maccabee's victory over the Seleucids and subsequent miracles.

Hasmonean Kingdom

On Jonathan's death in 142 B.C.E., Simon Maccabeus, the last remaining son of Mattathias, took power. Simon founded the Hasmonean dynasty, which lasted until 37 b.c.e.. The kingdom was the only independent Jewish state to exist in the four centuries after the Kingdom of Judah was destroyed in 586 B.C.E., and was one of the last before the modern state of Israel. Judah became an independent state in 141 B.C.E., Herod conquered Judah in 37 B.C.E., and rebuilt the Temple in 19 B.C.E.

The Jewish Kingdom of Judea controlled most of the region of Palestine (without the Negev but with the West Bank, Golan, and parts of the Gaza Strip) and parts of eastern Jordan. After approximately a century of independence disputes between the Hasmonean rivals Aristobulus II and Hyrcanus II led to control of the kingdom by the Roman army of Pompey.

Roman occupation

Rome's involvement in the area dated from 63 B.C.E., after the Third Mithridatic War, when Rome made Syria a province. Judea's Hasmonean Kingdom—first a client kingdom of the Roman Empire, after year 6 C.E. the Iudaea Province—were in nearly constant revolt against Roman occupation. The First Jewish-Roman War began in 66 C.E. and resulted in the destruction of Jewish temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E.

Around 40-39 B.C.E., Herod the Great was appointed King of the Jews by the Roman Senate. Prosperity marked his long reign (37–4 B.C.E.). Between 31 and 20, Caesar Augustus restored to Herod the Jewish territories that Pompey had taken, and Herod created an efficient Hellenistic administrative system. With nine wives and a large family, Herod had succession problems, which he tried to solve by having his wife Mariamne and several sons killed. His death in 4 B.C.E. led to a period of rule divided between his three surviving sons, which led to the return of direct Roman government.

Around 4 B.C.E., Jesus and John the Baptist were born. While Pontius Pilate was governor of Iudaea (26-36 C.E.), John the Baptist was beheaded, and Jesus was crucified. Jesus inspired what would eventually evolve, through Paul of Tarsus, into Christianity. Herod Agrippa I, appointed "King of the Jews" by Claudius, ruled from 41-44 C.E., and Herod Agrippa II, who ruled from 48-100 C.E., was the seventh and last of the Herodians.

Iudaea Province was the stage of three major rebellions — the Great Jewish Revolt (66-70 C.E.), the Kitos War (115-117 C.E.), and Bar Kokhba's revolt (132-135 C.E.). The incompetence and anti-Jewish bias of a Roman procurator resulted in the destruction of the Jewish Temple in 70 C.E. The last revolt was sparked when the emperor Hadrian announced plans to build a Roman colony, Aelia Capitolina, on the site of Jerusalem. The revolt was ruthlessly repressed — almost 1000 villages were destroyed and more than half a million people killed. Hadrian expelled most Jews from Judea on the pain of death, leaving large Jewish populations in Samaria and the Galilee. Tiberias became the headquarters of exiled Jewish patriarchs.

In an attempt to erase the historical ties of the Jewish people to the region, and to humiliate the defeated Jews, Hadrian changed the name of the province to Syria Palaestina, after the Philistines, whom the Romans identified as the worst enemies of the Jews. From then on the region was known as Palestine. Hadrian rebuilt Jerusalem as a Greco-Roman city, with a circus, an amphitheatre, baths, a theatre and with streets laid out in a grid pattern. Jews were initially banned, and later allowed for one yearly visit.

Constantine converts

Emperor Constantine's conversion to Christianity around 330 C.E. made Christianity the official religion of Palaestina. After his mother Empress Helena identified the spot she believed to be where Christ was crucified, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was built in Jerusalem. The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Ascension in Jerusalem were also built during Constantine's reign. Palestine thus became a center for pilgrims and ascetic life for men and women from all over the world. Many monasteries were built including the Saint George Monastery in Wadi al-Qilt, Deir Quruntul and Deir Hijle near Jericho, and Deir Mar Saba and Deir Theodosius east of Bethlehem.

In 352, a Jewish revolt against Byzantine/Roman rule in Tiberias and other parts of the Galilee was brutally suppressed by Gallus Caesar. Under Marcian (450–457) and again under Justinian I (527–565), the Samaritans revolted.

Constantine added the southern part of Arabia to the province, but later made the addition a separate province, later called Palaestina Tertia or Salutaris. By the end of the fourth century, Palaestina was further organised into three units: Palaestina Prima, Secunda, and Tertia (First, Second, and Third Palestine).Palaestina Prima consisted of Judea, Samaria, the coast, and Perea (Holy Land) with the governor residing in Caesarea. Palaestina Secunda consisted of the Galilee, the lower Jezreel Valley, the regions east of Galilee, and the western part of the former Decapolis with the seat of government at Scythopolis. Palaestina Tertia included the Negev, southern Jordan — once part of Arabia — and most of Sinai with Petra as the usual residence of the governor. Palestina Tertia was also known as Palaestina Salutaris.

In 536 C.E., Justinian I promoted the governor at Caesarea to proconsul (anthypatos), giving him authority over the two remaining consulars. Justinian believed that the elevation of the governor was appropriate because he was responsible for "the province in which our Lord Jesus Christ... appeared on earth". This was also the principal factor explaining why Palestine prospered under the Christian Empire. The cities of Palestine, such as Caesarea Maritima, Jerusalem, Scythopolis, Neapolis, and Gaza reached their peak population in the late Roman period and produced notable Christian scholars in the disciplines of rhetoric, historiography, Eusebian ecclesiastical history, classicizing history and hagiography.

Byzantine administration of Palestine was temporarily suspended during the Persian occupation of 614–28, and then permanently after the Muslims arrived in 634 C.E., defeating the empire's forces decisively at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636 C.E. Jerusalem capitulated in 638 C.E., and Caesarea between 640 C.E. and 642 C.E.

Covenant with the Caliphate

The Islamic unification of the Arabian Peninsula by the first caliph, Abu Bakr (632–634), led to Arab expansion into southern and south-eastern Syria. His successor, caliph Omar Ibn al-Khattab (634–644) continued the expansion. Jerusalem was the third holiest spot in Islam. In 638 Caliph Umar and Safforonius, the Byzantine governor of Jerusalem, signed Al-Uhda al-'Omariyya (The Umariyya Covenant), an agreement that stipulated the rights and obligations of all non-Muslims in Palestine. Jews were permitted to return to Palestine for the first time since the 500-year ban enacted by the Romans and maintained by Byzantine rulers.

Caliph Umar (634–644) was the first conqueror of Jerusalem to enter the city on foot, and when visiting the site that now houses the Haram al-Sharif, he declared it a sacred place of prayer. Cities that accepted the new rulers, as recorded in registrars from the time, were: Jerusalem, Nablus, Jenin, Acre, Tiberias, Bisan, Caesarea, Lajjun, Lydd, Jaffa, Imwas, Beit Jibrin, Gaza, Rafah, Hebron, Yubna, Haifa, Safad and Askalan.

Umayyad rule

Under Umayyad rule (661-750), the province of ash-Sham (Arabic for Greater Syria), of which Palestine was a part, was divided into five districts. It was one of the main provinces of the empire. Jund Filastin (Arabic جند فلسطين, literally "the army of Palestine") was a region extending from the Sinai to the plain of Acre. Major towns included Rafah, Caesarea, Gaza, Jaffa, Nablus and Jericho. Initially Lod was the capital, but in 717 the newly established city of Ramleh became the capital. Jund al-Urdunn (literally "the army of Jordan") was a region to the north and east of Filastin. Major towns included Legio, Acre, Bisan and Tyre and the capital was at Tiberias. Each jund was administered by an emir assisted by a financial officer. This pattern continued until the time of Ottoman rule.

The Umayyads paid special attention to Palestine – it was important in their struggle against Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula. In 691, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ordered that the Dome of the Rock be built on the site of the Temple of Solomon, where the Prophet Muhammed is believed by Muslims to have begun his nocturnal journey to heaven, on the Temple Mount. Close to the shrine and to the south about a decade afterward, Caliph Al-Walid I had the larger Al-Aqsa Mosque built .

Conversions to Islam, together with immigration, meant the Christian population gradually became predominantly Muslim and Arabic-speaking. During the early years of Muslim control, a small permanent Jewish population returned to Jerusalem after a 500-year absence. It was under Umayyad rule that Christians and Jews were granted the official title of "Peoples of the Book" to underline the common monotheistic roots they shared with Islam.

Abbasid rule

Palestine was not as central to the Abbasid rulers (750-969 ), though the Baghdad-based Abbasid Caliphs did visit the holy shrines and sanctuaries in Jerusalem and continued to build up Ramleh. Enmity between Umayyads and Abbasids became a political factor in Palestine, and pro-Umayyad uprisings were frequent. Coastal areas were settled and fortified to secure it against the Byzantine enemy. Port cities like Acre, Haifa, Caesarea, Arsuf, Jaffa and Ashkelon received monies from the state treasury.

A trade fair took place in Jerusalem every year on September 15 where merchants from Pisa, Genoa, Venice and Marseilles converged to acquire spices, soaps, silks, olive oil, sugar and glassware in exchange for European products. European Christian pilgrims visited and made generous donations to Christian holy places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

Palestine sustained an insurrection in 903–906 of the Qarmatians, an Isma’ili Shi'ite sect. After Abbasid authority was restored, Palestine came under Ikhshidid rule (935–969).

Fatimid rule

From their base in Tunisia, the Fatimids (969 – 1099 C.E.), who claimed to be descendants of the Prophet Muhammed through his daughter Fatima, conquered Palestine by way of Egypt in 969 C.E. The Fatimids established precarious control over Palestine, where they faced opposition from Qarmatians, Seljuks, Byzantines, and Bedouins. Palestine was often reduced to a battlefield, although Jerusalem, Nablus, and Askalan were expanded and renovated under their rule.

Fatimid caliph al-Hakim (996–1021) reactivated discriminatory laws imposed on Christians and Jews and added new ones. In 1009, he ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which was severely damaged as a result.

After the tenth century, the division into Junds began to break down. In 1071, the Isfahan-based Seljuk Turks captured Jerusalem, which prospered as pilgrimages by Jews, Christians, and Muslims increased. The Fatimids recaptured the city in 1098, only to lose it a year later to a new enemy, the Crusaders of western Europe.

Crusader rule

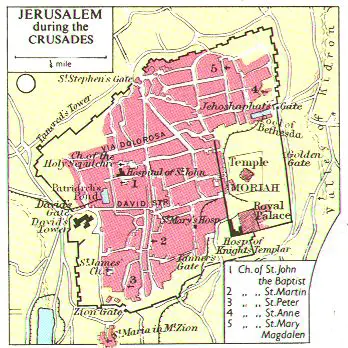

The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem was established on Christmas Day, 1100. This was a Christian kingdom which lasted less than 200 years, until 1291 when the last remaining outpost, Acre, was destroyed by the Mamluks. At first the kingdom was little more than a loose collection of towns and cities captured during the crusade. At its height, the Kingdom roughly encompassed the territory of modern Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip; it extended from modern Lebanon in the north to the Sinai Desert in the south, and into modern Jordan and Syria in the east. There were also attempts to expand the kingdom into Fatimid Egypt. Its kings also held a certain amount of authority over the other crusader states, Tripoli, Antioch, and Edessa.

Under the European rule, fortifications, castles, towers and fortified villages were built, rebuilt and renovated across Palestine largely in rural areas. A notable urban remnant of the Crusader architecture of this era is found in Acre's old city.

At first the Muslim world had little concern for the fledgling kingdom, but as the twelfth century progressed, the notion of jihad was resurrected, and the kingdom's increasingly-united Muslim neighbours vigorously began to recapture lost territory.

In July 1187, the Cairo-based Kurdish General Saladin commanded his troops to victory in the Battle of Hattin. Saladin went on to take Jerusalem. The Ayyubid Sultanate, founded by Saladin, controlled Jerusalem from 1187-1244, and some but not all of the region until 1250, when it was defeated by the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. An agreement granting special status to the Crusaders allowed them to continue to stay in Palestine and in 1229, Frederick II negotiated a 10-year treaty that placed Jerusalem, Nazareth and Bethlehem once again under Crusader rule.

In 1270, Sultan Baibars expelled the Crusaders from most of the country, though they maintained a base at Acre until 1291. Thereafter, any remaining Europeans either went home or merged with the local population.

Mamluk rule

A mamluk was a slave soldier who was converted to Islam and served the Muslim caliphs and the Ayyubid sultans during the Middle Ages. Over time they became a powerful military caste, and on more than one occasion they seized power for themselves, for example, ruling Egypt in the Mamluk Sultanate from 1250-1517. Palestine formed a part of the district of Damascus under the rule of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt (1270–1516), and was divided into three smaller districts with capitals in Jerusalem, Gaza, and Safad. Celebrated by Arab and Muslim writers of the time as the "blessed land of the Prophets and Islam's revered leaders," Muslim sanctuaries were "rediscovered" and received many pilgrims.

While during the first half of the Mamluk era (1270-1382), many schools, lodgings for travellers (khans) were built and mosques neglected or destroyed during the Crusader period were renovated, the second half (1382-1517) was a period of decline as the Mamluks were engaged in battles with the Mongols in areas outside Palestine.

In 1486, hostilities broke out between the Mamluks and the Ottoman Turks in a battle for control over western Asia. The Mamluk armies were eventually defeated by the forces of the Ottoman Sultan, Selim I, and lost control of Palestine after the 1516 battle of Marj Dapiq .

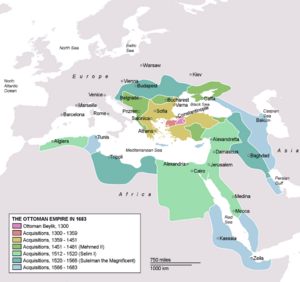

Ottoman rule

Ottoman rule lasted from 1516-1917. In 1516 the Ottoman Turks occupied Palestine, and the country became part of the Ottoman Empire. Constantinople appointed local governors. Public works, including the city walls, were rebuilt in Jerusalem by Suleiman the Magnificent in 1537. An area around Tiberias was given to Don Joseph HaNasi for a Jewish enclave. Following the expulsions from Spain, the Jewish population of Palestine rose to around 25 percent (including non-Ottoman citizens, and excluding Bedouins) and regained its former stronghold of Eastern Galilee. That ended in 1660 when they were massacred at Safed and Jerusalem. During the reign of Dahar al Omar, Pasha of the Galilee, Jews from Ukraine began to resettle Tiberias.

Napoleon of France briefly waged war against the Ottoman Empire (allied then with Great Britain). His forces conquered and occupied cities in Palestine, but they were finally defeated and driven out by 1801. In 1799 Napoleon Napoleon announced a plan to re-establish a Jewish State in Palestine which was mostly to curry favour with Haim Farkhi the Jewish finance minister and advisor to the Pasha of Syria/Palestine. He was later assassinated and his brothers formed an army with Ottoman permission to conquer the Galilee.

Jewish immigration to Palestine, particularly to the "four sacred cities" (Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias and Hebron) which already had significant Jewish communities, increased particularly towards the end of Ottoman rule; Jews of European origin lived mostly off donations from off-country, while many Sephardic Jews found themselves a trade. Many Circassians and Bosnian Muslims were settled in the north of Palestine by the Ottomans in the early nineteenth century. In the 1830s Egypt conquered Palestine and made some minor improvements and many Egyptians, in particular soldiers, settled there. It was however during this period that the Jews of Safed were massacred in 1831 by Druzes. Safed was resettled with Kurds and Algerians. This was followed in 1837 by earthquakes in Safed and Tiberias. In 1838 Palestine was returned to the Turks.

After the Ottoman conquest, the name "Palestine" disappeared as the official name of an administrative unit, as the Turks often called their (sub)provinces after the capital. Since its 1516 incorporation in the Ottoman Empire, it was part of the vilayet (|province) of Damascus-Syria until 1660, next of the vilayet of Sidon (Sidon). Still the old name remained in popular and semi-official use. Many examples of its usage in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have survived. During the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Government employed the term Arz-i Filistin (the 'Land of Palestine') in official correspondence, meaning the area to the west of the River Jordan. Among the educated Arab public, Filastin was a common concept, referring either to the whole of Palestine or to the Jerusalem sanjaq alone, or just to the area around Ramle.

Ottoman rule over the region lasted until the Great War (World War I) when the Ottomans sided with Germany and the Central Powers. During World War I, the Ottomans were driven from much of the area by the United Kingdom during the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

Zionism and Jewish immigration

Theodor Herzl (1860–1904), an Austro-Hungarian Jew, founded the Zionist movement. In 1896, he published Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), in which he called for the establishment of a national Jewish state. The following year he helped convene the first World Zionist Congress. Moses Hess and others called for the "redemption of the soil." The rise of Zionism increased the trend of Jewish immigration. The first big wave of modern Jewish immigration started in 1881 as Jews fled growing persecution in Russia. The Second Aliyah (1904–1914) brought an influx of around 40,000 Jews. Jews bought land from individual Arab landholders.

Towards the end of the nineteenth and in the early years of the twentieth centuries, Palestinian Arabs shared in an Arab renaissance. Palestinian deputies sat in the Ottoman parliaments, and Arabic newspapers appeared, displaying strong Arab nationalism and opposition to Jewish immigration and land purchases. There were 19 Zionist colonies in Palestine in 1900, while in 1918 there were 47. Most were subsidized by the French philanthropist Edmond baron de Rothschild.

World War I

Up to World War I, the word "Palestine" was used informally for a region that extended in the north-south direction typically from Raphia (south-east of Gaza) to the Litani River (now in Lebanon). The western boundary was the sea, and the eastern boundary was the poorly defined place where the Syrian desert began. In various European sources, the eastern boundary was placed anywhere from the Jordan River to slightly east of Amman. The Negev Desert was not included.

In World War I, Turkey sided with Germany. As a result, it was embroiled in a conflict with Great Britain. The British-led Egyptian Expeditionary Force, commanded by Edmund Allenby, captured Jerusalem on December 9, 1917, and occupied the whole of the Levant following the defeat of Turkish forces in Palestine at the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918 and the capitulation of Turkey on October 31. At the subsequent 1919 Paris Peace Conference and Treaty of Versailles, Turkey's loss of its Middle East empire was formalized.

During World War I, the great powers made a number of decisions about Palestine without regard to the people of the region. Palestinian Arabs believed 1915-16 correspondence between the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, and the Emir of Mecca, Hussein ibn Ali, indicated an undertaking to form an Arab state, in return for Arab support against the Ottomans during the war. Yet, the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, envisioned that most of Palestine, when freed from Ottoman control, would become an international zone not under direct French or British colonial control. A further complication came when British foreign minister Arthur Balfour issued the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which laid plans for a Jewish homeland to be established in Palestine eventually, while respecting the rights of the indigenous majority.

At the end of the war, the future of Palestine was a problem. Great Britain had set up a military administration there after capturing Jerusalem. On March 20, 1920, Palestinian delegates at a general Syrian congress at Damascus, passed a resolution rejecting the Balfour Declaration and electing Faisal I, the son of Hussein ibn Ali, who ruled the Hejaz, the king of a united Syria, which included Palestine.

Ottoman territories divided

In April 1920, the Allied Supreme Council meeting at San Remo, Italy, divided the former territories of the defeated Ottoman Empire. Syria and Lebanon were mandated to France, and Palestine was mandated to Britain. The British Mandate of Palestine lasted from 1920 to 1948. In July 1920, the French drove Faisal I of Iraq from Damascus ending his already negligible control over Transjordan, where local chiefs traditionally resisted any central authority. The hope of founding an Arab Palestine within a federated Syrian state collapsed. Palestinian Arabs referred to 1920 as “am al-nakbah”, the “year of catastrophe.”

After Jews established agricultural settlements, tensions erupted between the Jews and Arabs. By 1920, the Jewish population of Palestine had reached 11 percent of the population. In April 1920, anti-Zionist riots broke out in Jerusalem, killing several and injuring many. The British installed a civilian administration in July of that year, and a Zionist Sir Herbert Samuel became the first high commissioner. He proceeded to implement the Balfour Declaration, and announced a quota of 16,500 Jewish immigrants for the first year.

Arab opposition grows

In December 1920, Palestinian Arabs at a congress in Haifa set up the Arab Executive, which declared Palestine was an autonomous Arab entity and rejected any rights of the Jews to Palestine. Meanwhile, Jewish immigration into the region increased — in the third (1919–1923), and fourth (1924–1929) waves. The arrival of more than 18,000 Jewish immigrants between 1919 and 1921 and land purchases in 1921 by the Jewish National Fund, and the eviction of Arab peasants (fellahin), led to anti-Zionist riots in Jaffa, on May 1, 1921, which spread to Petah Tiqwa and other communities. About 100 people were killed.

On April 11, 1921, the British passed administration of the eastern region to the Hashemite Arab dynasty from the Hejaz what later became part of Saudi Arabia as the Emirate of Transjordan and on 15 May 1923 recognized it as a state.

An Arab delegation visited London in late 1921, demanding repudiation of the Balfour Declaration and proposing the creation of a national government with a parliament elected by Muslims, Christians, and Jews. The British government issued a White Paper in June 1922 declaring that while Britain did not intend that all of Palestine should become a Jewish national home, such a home should be founded within Palestine, that immigration would not exceed levels the country could absorb, and that steps would be taken to set up a legislative council. Arabs rejected these proposals.

British Mandate

In July 1922, the League of Nations approved the mandate for Palestine, accepted the preamble incorporating the Balfour Declaration, and affirmed the Jewish historical connection with Palestine.

The British Mandate of Palestine, lasted from 1920 to 1948, and covered terrirories later comprising Jordan, Israel, and territories governed in different degrees of control by the Palestinian Authority. It was originally bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the West, the French Mandate of Lebanon, French Mandate of Syria, and the British Mandate of Mesopotamia to the North, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to the East and South, and the Kingdom of Egypt to the Southwest.

This distinct Palestinian political entity, the first for centuries, created problems for Palestinian Arabs and Zionists alike. The central issues were Jewish immigration and land purchases, conflict over which often escalated into violence.

Formal use of the English word "Palestine" returned with the British Mandate, which enacted English, Hebrew and Arabic as its three official languages. Palestine became the formal name of the entity in English and Arabic while Palestina (Eretz Yisrael) ((פלשתינה (א"י) was the formal name in Hebrew.

Arab administration

Traditional rivalry between two old Jerusalem families, the Husaynis and the Nashashibis, whose members had held government posts in the late Ottoman period, helped fragment Arab leadership. In 1921, the British appointed Amin al-Husseini to be the mufti of Jerusalem, and made him president of the new Supreme Muslim Council, which controlled the Muslim courts and schools and funds raised by religious charities. The anti-British Husseini famil led most Arab groups opposing Jewish immigration.

Jewish administration

The World Zionist Organization was regarded as the “Jewish agency” set out in the mandate. Its president, Chaim Weizmann, worked from London, close to the British government, while Polish-born David Ben-Gurion led an executive in Palestine. The Palestine Jewish community set up its own assembly (Va'ad Leumi), labour movement (Histadrut), schools, courts, taxation system, medical services, industrial enterprises, and a military organization called the Haganah. The Labour Zionists, who believed in cooperation with the British and Arabs, controlled the Jewish Agency. Another group, the Revisionist Zionists, led by Vladimir Jabotinsky, recognized their goal of a Jewish state in all of Palestine clashed with that of Palestinian Arabs, and formed their own military wing, Irgun, which used force against the Arabs.

Riots

Jews bought large tracts of land from often absentee Arab owners. In August 1929, an enlarged Jewish Agency included non-Zionist Jewish sympathizers throughout the world. A dispute in Jerusalem concerning the Western Wall, the only remnant of the Second Temple as well as the site of the Dome of the Rock—sparked fighting in which 250 were killed and 570 wounded.

The British government conducted an inquiry and issued the Passfield White Paper, in October 1930, which called for a halt to Jewish immigration, recommended that land be sold only to landless Arabs, and that the question of “economic absorptive capacity” be based on levels of Arab and Jewish unemployment. Palestinian Jews and London Zionists protested, and in February 1931, the British prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, wrote to Chaim Weizmann nullifying the Passfield White Paper. Arabs saw that recommendations made in Palestine could be annulled by Zionist influence at in London, so in December 1931, a Muslim congress in Jerusalem attended by delegates from 22 countries warned against the danger of Zionism.

Arab rebellion

The Nazi rise to power in Germany in 1933 and persecution of Jews throughout Europe increased Jewish immigration, which rose to 30,000 in 1933, 42,000 in 1934, and 61,000 in 1935, provoking acts of violence against Jews and the British in 1933 and 1935. The Arab population of Palestine also grew rapidly. A further Arab demand to end Jewish immigration cease, prohibit land transfer, and establish democratic institutions be established led nowhere. Rising nationalism in Egypt and Syria, increasing unemployment in Palestine, and a poor citrus harvest, touched off an Arab revolt, from 1936-39.

In April 1936, two Jews were murdered, violence escalated, and Arab groups started a general strike in Jaffa and Nabulus. The Jerusalem mufti presided over an Arab high committee, that repeated demands for the end of Jewish immigration and land sales, and independence, as well as calling for a general strike, a tax revolt, and closure of government offices. Meanwhile, Arab rebels and volunteers from other countries attacked Jewish settlements.

A British inquiry, the Peel Commission, in July 1937, declared the mandate unworkable, recommended that the region be partitioned, recommended an area much greater than existing Jewish land holdings, and advocated the transfer by force of the Arab population. Horrified, Arabs escalated the revolt, until In September 1937 the British declared martial law.

The revolt left more than 5000 Arabs dead, 15,000 wounded, and 5600 were imprisoned. The general strike encouraged Zionist self-reliance, the revolt united Jewish settlers behind Ben-Gurion, and the Haganah were given permission to arm itself. Traditional Arab leaders were either killed, arrested, or deported, leaving a dispirited, disarmed and divided Arab population.

A subsequent Woodhead Commission report In November 1938 recommended against the Peel Commission's plan and put forward an alternative which drastically reduced the area of the Jewish state and limited the sovereignty of the proposed states. In May 1939, the British government White Paper said that the Jewish national home should be established within an independent Palestinian state, and that Jewish immigration would be limited to 75,000 during the next five years, after which Jewish immigration would be subject to Arab agreement. Both Arabs and Zionists rejected the White Paper, which marked the end of cordial relations between Zionism and the British government.

By 1940, the number of rural Zionist colonies had increased to about 200, Jewish landholdings had risen to 383,500 acres, or one-seventh of the cultivatable land, the Jewish population had reached 467,000, about one-third of a total population of about 1,528,000, and Tel Aviv was an all-Jewish city of 150,000 inhabitants.

World War II

Between 1939 and 1945 German Nazis killed more than six million Jews in the Holocaust, a horror that gave new impetus to the movement to form a Jewish state. British attempts to prevent Jewish immigration to Palestine in the face of the Holocaust led to the disastrous sinking of two ships carrying Jewishh refugees — the Patria (November 1940) and the Struma (February 1942). In response, the Irgun, led by Menachem Begin, and LEHI (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel), also known as the Stern Gang, launched attacks on the British, culminating in the murder of Lord Moyne, a British minister of state, in Cairo in November 1944.

Arabs in Palestine remained quiet throughout the war. Amin al-Husseini had fled to Germany, from where he tried to rally Arabs in support of the Axis powers against Britain and Zionism. Most supported the Allies— approximately 23,000 Arabs enlisted in the British forces, as did 27,000 Jews.

In August 1945, U.S. President Harry S Truman asked British Prime Minister Clement Attlee to allow 100,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors into Palestine. In October 1944, Arab heads of state issued the Alexandria Protocol, which said that although they regretted the bitter fate inflicted upon European Jewry, solving the problem of European Jewry should not be achieved by inflicting injustice on Palestinian Arabs. The Arab League, formed in March 1945, appointed an Arab Higher Executive for Palestine (the Arab Higher Committee), and later declared a boycott of Zionist goods.

xxx In the years following World War II, Britain's position in Palestine gradually worsened. This was caused by a combination of factors, including:

- Rapid deterioration due to the incessant attacks by Irgun and Lehi on British officials, armed forces, and strategic installations. This caused severe damage to British morale and prestige, as well as increasing opposition to the mandate in Britain itself, public opinion demanding to "bring the boys home".[2]

- World public opinion turned against Britain as a result of the British policy of preventing the Jewish Zionist Holocaust survivors from reaching Palestine, sending them instead to refugee camps in Cyprus, or even back to Germany, as in the case of Exodus 1947.

- The costs of maintaining an army of over 100,000 men in Palestine weighed heavily on a British economy suffering from post-war depression, and was another cause for British public opinion to demand an end to the Mandate.

Finally in early 1947 the British Government announced their desire to terminate the Mandate, and passed the responsibility over Palestine to the United Nations.

UN partition

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly, with a two-thirds majority international vote, passed the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine (United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181), a plan to resolve the Arab-Jewish conflict by partitioning the territory into separate Jewish and Arab states, with the Greater Jerusalem area (encompassing Bethlehem) coming under international control. Jewish leaders (including the Jewish Agency), accepted the plan, while Palestinian Arab leaders rejected it and refused to negotiate. Neighboring Arab and Muslim states also rejected the partition plan. The Arab community reacted violently after the Arab Higher Committee declared a strike and burned many buildings and shops. As armed skirmishes between Arab and Jewish paramilitary forces in Palestine continued, the British mandate ended on May 15, 1948, the establishment of the State of Israel having been proclaimed the day before (see Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel). The neighboring Arab states and armies (Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Transjordan, Holy War Army, Arab Liberation Army, and local Arabs) immediately attacked Israel following its declaration of independence, and the 1948 Arab-Israeli War ensued. Consequently, the partition plan was never implemented.

Current status

Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and neighboring Arab states eliminated Palestine as a distinct territory. With the establishment of Israel, the remaining lands were divided amongst Egypt, Syria and Jordan.

In addition to the UN-partitioned area it was allotted, Israel captured 26% of the Mandate territory west of the Jordan river. Jordan captured and annexed about 21% of the Mandate territory, known today as the West Bank. Jerusalem was divided, with Jordan taking the eastern parts, including the Old City, and Israel taking the western parts. The Gaza Strip was captured by Egypt.

For a description of the massive population movements, Arab and Jewish, at the time of the 1948 war and over the following decades, see Palestinian exodus and Jewish exodus from Arab lands.

From the 1960s onward, the term "Palestine" was regularly used in political contexts. Various declarations, such as the 15 November 1988 proclamation of a State of Palestine by the PLO referred to a country called Palestine, defining its borders based on the U.N. Resolution 242 and 383 and the principle of Land for Peace. The Green Line was the 1967 border established by many UN resolutions including those mentioned above.

In the course of the Six Day War of June 1967, Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan and Gaza from Egypt.

According to the CIA World Factbook,[3] of the ten million people living between Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea, 49% identify as Palestinian, Arab, Bedouin and/or Druze. One million of those are citizens of Israel. The other four million are stateless residents of the West Bank and Gaza. In the meantime, they live under Palestinian National Authority jurisdiction, subject to conditions imposed by Israel.

In the West Bank, 360,000 Israeli settlers live in a hundred scattered settlements with connecting corridors. The 2.5 million West Bank Palestinians live in four blocks centered in Hebron, Ramallah, Nablus, and Jericho, while Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005.

Demographics

Early demographics

Estimating the population of Palestine in antiquity relies on 2 methods - censuses and writings made at the times, and the scientific method based on excavations and statistical methods that consider the number of settlements at the particular age, area of each settlement, density factor for each settelment.

According to Joseph Jacobs, writing in the Jewish Encyclopedia[4] (1901-1906), the Pentateuch contains a number of statements as to the number of Jews that left Egypt, the descendants of the seventy sons and grandsons of Jacob who took up their residence in that country. Altogether, including Levites, there were 611,730 males over twenty years of age, and therefore capable of bearing arms; this would imply a population of about 3,154,000. The Census of David is said to have recorded 1,300,000 males over twenty years of age, which would imply a population of over 5,000,000. The number of exiles who returned from Babylon is given at 42,360. Tacitus declares that Jerusalem at its fall contained 600,000 persons; Josephus, that there were as many as 1,100,000. According to Israeli archeologist Magen Broshi, "... the population of Palestine in antiquity did not exceed a million persons. It can also be shown, moreover, that this was more or less the size of the population in the peak period—the late Byzantine period, around A.D. 600"[5] Similarly, a study by Yigal Shiloh of The Hebrew University suggests that the population of Palestine in the Iron Age could have never exceeded a million. He writes: "... the population of the country in the Roman-Byzantine period greatly exceeded that in the Iron Age...If we accept Broshi's population estimates, which appear to be confirmed by the results of recent research, it follows that the estimates for the population during the Iron Age must be set at a lower figure."[6]

Shmuel Katz writes: [7]

"When Jewish independence came to an end in the year 70, the population numbered, at a conservative estimate, some 5 million people. (By Josephus' figures, there were nearer 7 million.) Even sixty years after the destruction of the Temple, at the outbreak of the revolt led by Bar Kochba in 132, when large numbers had fled or been deported, the Jewish population of the country must have numbered at least 3 million, according to Dio Cassius' figures. Sixteen centuries later, when the practical possibility of the return to Zion appeared on the horizon, Palestine was a denuded, derelict, and depopulated country. The writings of travellers who visited Palestine in the late eighteenth and throughout the nineteenth century are filled with descriptions of its emptiness, its desolation. In 1738, Thomas Shaw wrote of the absence of people to fill - Palestine's fertile soil. In 1785, Constantine Francois Volney described the "rained" and "desolate" country. He had not seen the worst. Pilgrims and travellers continued to report in heartrending terms on its condition. Almost sixty years later, Alexander Keith, recalling Volney's description, wrote: "In his day the land had not fully reached its last degree of desolation and depopulation."[8]

The table below represents estimates of the first century population of Palestine (as adapted from Byatt, 1973).

| Authority | Jews | Total population1 |

|---|---|---|

| Condor , C R[9] | - | 6 million |

| Juster, J[10] | 5 million | >5 million |

| Mazar, Benjamin[11] | - | >4 million |

| Klausner, Joseph[12] | 3 million | 3.5 million |

| Grant, Michael[13] | 3 million | not given |

| Baron, Salo W[14] | 2-2.5 million | 2.5-3 million |

| Socin, A[15] | - | 2.5-3 million |

| Lowdermilk, W C[16] | - | 3 million |

| Avi-Yonah, M[17] | - | 2.8 million |

| Glueck, N[18] | - | 2.5 million |

| Beloch, K J[19] | 2 million | not given |

| Grant, F C[20] | - | 1.5-2.5 million |

| Byatt, A[21] | - | 2.265 million |

| Daniel-Rops, H[22] | 1.5 million | 2 million |

| Derwacter, F M[23] | 1 million | 1.5 million |

| Pfeiffer, R H[24] | 1 million | not given |

| Harnack, A[25] | 500,000 | not given |

| Jeremias, J[26] | 500,000-600,000 | not given |

| McCown, C C[27] | <500,000 | <1 million |

1. There is no consensus on the population of Palestine in the first century of the Common Era; estimates range from under 1 million to 6 million.

Demographics in the late Ottoman and British Mandate periods

In the middle of the first century of the Ottoman rule, i.e. 1550 C.E., Bernard Lewis in a study of Ottoman registers of the early Ottoman Rule of Palestine reports[28]

From the mass of detail in the registers, it is possible to extract something like a general picture of the economic life of the country in that period. Out of a total population of about 300,000 souls, between a fifth and a quarter lived in the six towns of Jerusalem, Gaza, Safed, Nablus, Ramle, and Hebron. The remainder consisted mainly of peasants, living in villages of varying size, and engaged in agriculture. Their main food-crops were wheat and barley in that order, supplemented by leguminous pulses, olives, fruit, and vegetables. In and around most of the towns there was a considerable number of vineyards, orchards, and vegetable gardens.

By Volney's estimates in 1785, there were no more than 200,000 people in the country.[29]

In his paper 'Demography in Israel/Palestine: Trends, Prospects and Policy Implications'[30] Sergio DellaPergola, drawing on the work of Bachi (1975), provides rough estimates of the population of Palestine west of the River Jordan by religion groups from the first century onwards summarised in the table below.

| Year | Jews | Christians | Muslims | Total1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First half 1st century C.E. | Majority | - | - | ~2,5002 |

| 5th century | Minority | Majority | - | >1st century |

| End 12th century | Minority | Minority | Majority | >225 |

| 14th cent. before Black Death | Minority | Minority | Majority | 225 |

| 14th cent. after Black Death | Minority | Minority | Majority | 150 |

| 1533-1539 | 5 | 6 | 145 | 157 |

| 1690-1691 | 2 | 11 | 219 | 232 |

| 1800 | 7 | 22 | 246 | 275 |

| 1890 | 43 | 57 | 432 | 532 |

| 1914 | 94 | 70 | 525 | 689 |

| 1922 | 84 | 71 | 589 | 752 |

| 1931 | 175 | 89 | 760 | 1,033 |

| 1947 | 630 | 143 | 1,181 | 1,970 |

1. Figures in thousands. The total includes Druzes and other small religious minorities.

2. There is no consensus on the population of Palestine in the first century of the Christian Era; estimates range from under 1 million to 6 million.

According to Alexander Scholch, the population of Palestine in 1850 had about 350,000 inhabitants, 30% of whom lived in 13 towns; roughly 85% were Muslims, 11% were Christians and 4% Jews[31]

| Qazas | Number of Towns and Villages |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muslims | Christians | Jews | Total | |||

| 1 | Jerusalem | |||||

| Jerusalem | 1 | 1,025 | 738 | 630 | 2,393 | |

| Countryside | 116 | 6,118 | 1,202 | 7,320 | ||

| 2 | Hebron | |||||

| Hebron | 1 | 2,800 | 200 | 3,000 | ||

| Countryside | 52 | 2,820 | 2,820 | |||

| 3 | Gaza | |||||

| Gaza | 1 | 2,690 | 65 | 2,755 | ||

| Countryside | 55 | 6,417 | 6,417 | |||

| 3 | Jaffa | |||||

| Jaffa | 3 | 865 | 266 | 1,131 | ||

| Ludd | . | 700 | 207 | 907 | ||

| Ramla | . | 675 | 250 | 925 | ||

| Countryside | 61 | 3,439 | 3,439 | |||

| 4 | Nablus | |||||

| Nablus | 1 | 1,356 | 108 | 14 | 1,478 | |

| Countryside | 176 | 13,022 | 202 | 13,224 | ||

| 5 | Jinin | |||||

| Jinin | 1 | 656 | 16 | 672 | ||

| Countryside | 39 | 2,120 | 17 | 2,137 | ||

| 6 | Ajlun | |||||

| Countryside | 97 | 1,599 | 137 | 1,736 | ||

| 7 | Salt | |||||

| Salt | 1 | 500 | 250 | 750 | ||

| Countryside | 12 | 685 | 685 | |||

| 8 | Akka | |||||

| Gaza | 1 | 547 | 210 | 6 | 763 | |

| Countryside | 34 | 1,768 | 1,021 | 2,789 | ||

| 9 | Haifa | |||||

| Haifa | 1 | 224 | 228 | 8 | 460 | |

| Countryside | 41 | 2,011 | 161 | 2,171 | ||

| 10 | Nazareth | |||||

| Nazareth | 1 | 275 | 1,073 | 1,348 | ||

| Countryside | 38 | 1,606 | 544 | 2,150 | ||

| 11 | Tiberias | |||||

| Tiberias | 1 | 159 | 66 | 400 | 625 | |

| Countryside | 7 | 507 | 507 | |||

| 12 | Safad | |||||

| Safad | 1 | 1,295 | 3 | 1,197 | 2,495 | |

| Countryside | 38 | 1,117 | 616 | 1,733 | ||

Figures from Ben-Arieh, in Scholch 1985, p. 388.

According to Ottoman statistics studied by Justin McCarthy,[32] the population of Palestine in the early 19th century was 350,000, in 1860 it was 411,000 and in 1900 about 600,000 of which 94% were Arabs. In 1914 Palestine had a population of 657,000 Muslim Arabs, 81,000 Christian Arabs, and 59,000 Jews.[33]

According to Howard Sachar, the Arab population of Palestine was about 260,000 in 1882. This number had doubled by 1914 and reached 600,000 by 1920 and 840,000 by 1931. Thus, between 1922 and 1946 the Arab population of Palestine increased by 118 percent, the highest rate of population growth among all Arab lands except Egypt.[34] McCarthy estimates the non-Jewish population of Palestine at 452,789 in 1882, 737,389 in 1914, 725,507 in 1922, 880,746 in 1931 and 1,339,763 in 1946.[35]

Traveller's impressions of Nineteenth Century Palestine

Alphonse de Lamartine visited Palestine in 1835, "Outside the gates of Jerusalem we saw indeed no living object, heard no living sound, we found the same void, the same silence ... as we should have expected before the entombed gates of Pompeii or Herculaneam a complete eternal silence reigns in the town, on the highways, in the country ... the tomb of a whole people.[36]

Mark Twain visited Palestine in 1867 and wrote in chapters 46,49,52 and 56 of Innocents Abroad: "Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies. Palestine is desolate and unlovely — Palestine is no more of this workday world. It is sacred to poetry and tradition, it is dreamland."(Chapter 56)[37] "There was hardly a tree or a shrub anywhere. Even the olive and the cactus, those fast friends of a worthless soil, had almost deserted the country".(Chapter 52)[38]"A desolation is here that not even imagination can grace with the pomp of life and action. We reached Tabor safely. We never saw a human being on the whole route".(Chapter 49) [39] "There is not a solitary village throughout its whole extent – not for thirty miles in either direction. ...One may ride ten miles hereabouts and not see ten human beings." ...these unpeopled deserts, these rusty mounds of barrenness..."(Chapter 46) [40]

Kathleen Christison was critical of Twain and noted that Twain described the Samaritans of Nablus at length without mentioning the large Arab population at all.[41] The Arab population at the time was about 20,000.[42]

During the nineteenth century, many residents and visitors attempted to estimate the population without recourse to official data, and came up with a large number of different values. Estimates that are reasonably reliable are only available for the final third of the century, from which period Ottoman population and taxation registers have been preserved.[43]

After a visit to Palestine in 1891, Ahad Ha'am wrote:

From abroad, we are accustomed to believe that Eretz Israel is presently almost totally desolate, an uncultivated desert, and that anyone wishing to buy land there can come and buy all he wants. But in truth it is not so. In the entire land, it is hard to find tillable land that is not already tilled; only sandy fields or stony hills, suitable at best for planting trees or vines and, even that after considerable work and expense in clearing and preparing them- only these remain unworked. ... Many of our people who came to buy land have been in Eretz Israel for months, and have toured its length and width, without finding what they seek.[44]

Meir Abelson writes: "In 1898, German Kaiser Wilhelm II also visited Palestine. He was appalled at the condition of the country. The Ottomans had stripped the forests for lumber and firewood. The Palestinian Arabs had let an old Roman aqueduct fall into ruin. The ultimate ecological curse was the ubiquitous herds of black goats. For nearly 2,000 years after the dispersion of the Jews, Arabs had allowed their goats to graze unfenced across Palestine. They had eaten the grass down to its roots, and the topsoil had eroded and blown away. The biblical land of milk and honey had become a dust bowl.[45]

However, there are travellers of that period who wrote about a fertile and green Palestine. Lawrence Oliphant, who visited Palestine in 1887, wrote that Palestine's Valley of Esdraelon was "a huge green lake of waving wheat, with its village-crowned mounds rising from it like islands; and it presents one of the most striking pictures of luxuriant fertility which it is possible to conceive."[46]

According to Paul Masson, a French economic historian, "wheat shipments from the Palestinian port of Acre had helped to save southern France from famine on numerous occasions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries."[47]

Walter C. Lowdermilk, Assistant Chief of the United States Soil Conservation Service has compared Palestine favorably to California:

The similarity of Southern California and Palestine is so close in climate, topography, soils and vegetation that the present condition of similarly placed areas in California is a reliable index of the early condition of the land of Palestine. Vegetation varied from desert scrub on lower slopes of the Jordan Valley and Dead Sea, to luxuriant forests of Cedars of Lebanon on the flanks of Mount Hermon, similar to the desert vegetation from Coachella Valley below sea level in Southern California to pine and fir forests on lower slopes of Mt. Baldy (10,000 feet) in the San Gabriel Range. Rainfall favours Palestine, for Jaffa gets more rain 2 1.5 inches) per annum than Los Angeles (15.2 inches), and the Mt. Hermon mountain land mass gets up to 70 inches of rain while Mt. Baldy only 50 inches. Other comparisons are striking. The region of the Jordan River, including Palestine and Trans-Jordan and the maritime slopes, is quite similar to California, but has an added advantage of its limestone country rock. The climates are alike, the natural vegetation, the physiographic features, except for the great limestone springs in Palestine. Similar crops may be grown. Differences are that soils of Palestine were uniformly better, that uplands have been badly eroded from misuse, and that slopes of Palestine favoured tree crops and were terraced where surface rock was ready at hand..".[48]

Official reports

In 1920, the League of Nations' Interim Report on the Civil Administration of Palestine stated that there were 700,000 people living in Palestine:

Of these 235,000 live in the larger towns, 465,000 in the smaller towns and villages. Four-fifths of the whole population are Moslems. A small proportion of these are Bedouin Arabs; the remainder, although they speak Arabic and are termed Arabs, are largely of mixed race. Some 77,000 of the population are Christians, in large majority belonging to the Orthodox Church, and speaking Arabic. The minority are members of the Latin or of the Uniate Greek Catholic Church, or—a small number—are Protestants.

The Jewish element of the population numbers 76,000. Almost all have entered Palestine during the last 40 years. Prior to 1850 there were in the country only a handful of Jews. In the following 30 years a few hundreds came to Palestine. Most of them were animated by religious motives; they came to pray and to die in the Holy Land, and to be buried in its soil. After the persecutions in Russia forty years ago, the movement of the Jews to Palestine assumed larger proportions.[49]

By 1948, the population had risen to 1,900,000, of whom 68% were Arabs, and 32% were Jews (UNSCOP report, including bedouin).

Genetic analyses of regional populations

According to various genetic studies, Jewish and Samaritan populations and various Palestinian populations overlap genetically because they share some of the same Neolithic ancestors.

Geneticists generally agree there was mixing in Middle East populations in prehistoric times. Nebel et al. (2000) doing Y-chromosome haplotype analysis for patrilineal ancestry of Jews and Palestinian Muslims "revealed a common gene pool for a large portion of Y chromosomes, suggesting a relatively recent common ancestry". The two modal haplotypes that comprise the Palestinian Arab clade were very infrequent among Jews, "reflecting divergence and/or admixture from other populations". Nebel et al. regard their findings in good agreement with historical evidence that suggest that "Part, or perhaps the majority, of the Muslim Arabs in this country descended from local inhabitants, mainly Christians and Jews, who had converted after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD... These local inhabitants, in turn, were descendants of the core population that had lived in the area for several centuries, some even since prehistoric times.[50]

A subsequent study aimed at determining the genetic relationship among three Jewish communities (Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Kurdish) by the same group described two Y-chromosomal haplotype groups, Eu9 and Eu10, that represent a major part of Middle East ancestry. Eu9 appears to originate from the northern Fertile Crescent, while Eu10 appears to come from the southern part of it. Jewish and Muslim Kurdish populations have high-frequency of Eu9 but generally lack Eu10, which is prevalent in Palestinian Muslims. The study proposes that

...the Y chromosomes in Palestinian Arabs and Bedouin represent, to a large extent, early lineages derived from the Neolithic inhabitants of the area and additional lineages from more-recent population movements. The early lineages are part of the common chromosome pool shared with Jews. According to our working model, the more-recent migrations were mostly from the Arabian Peninsula, as is seen in the Arab-specific Eu 10 chromosomes that include the modal haplotypes observed in Palestinians and Bedouin... The study demonstrates that the Y chromosome pool of Jews is an integral part of the genetic landscape of the region and, in particular, that Jews exhibit a high degree of genetic affinity to populations living in the north of the Fertile Crescent.[51]

The question of late Arab immigration to Palestine

Whether there was significant Arab immigration into Palestine after the beginning of Jewish settlement there in the late 19th century has been a matter of some controversy.

Howard Sachar estimates the number of Arabs who immigrated to Palestine between 1922 and 1946 at 100,000.[52] He argues that