Philistines

The historic Philistines (Hebrew: ◊§◊ú◊©◊™◊ô◊Ě, plishtim) were a people who inhabited the southern coast of Canaan around the time of the arrival of the Israelites, their territory being named Philistia in later contexts. Their origin has been debated among scholars, but modern archaeology has suggested early cultural links with the Mycenaean world in mainland Greece. Though the Philistines adopted local Canaanite culture and language before leaving any written texts, an Indo-European origin has been suggested for a handful of known Philistine words.

In the Hebrew Bible, the Philistines were usually portrayed as implacable enemies of the Israelites. Their most famous warrior was the gigantic spearman Goliath of Gath. At certain times, however, Israelite tribes allied themselves with the Philistines or paid tribute to them. Philistine civilization disappeared after its cities were conquered by the Assyrian Empire in the late eighth century B.C.E.

History

If the Philistines are to be identified as one of the "Sea Peoples" (see Origins below), then their occupation of Canaan would have to have taken place during the reign of Ramses III of the twentieth dynasty (c. 1180-1150 B.C.E.).

In Ancient Egypt, a people called the Peleset, generally identified with the Philistines, appear in the Medinet Habu inscription of Ramses III[1] where he describes his victory against the Sea Peoples. The Peleset also appear in the Onomastica of Amenope (late twentieth dynasty) and Papyrus Harris I, a summary of Ramses III's reign written during the reign of Ramses IV. Nineteenth-century Bible scholars identified the land of the Philistines (Philistia) with Palastu and Pilista in Assyrian inscriptions, according to Easton's Bible Dictionary (1897).

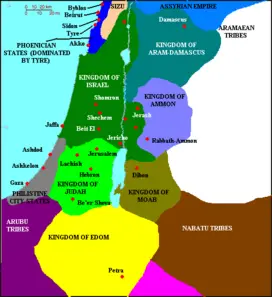

The Philistines occupied the five cities of Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath, along the coastal strip of southwestern Canaan that belonged to Egypt up to the closing days of the nineteenth dynasty (ended 1185 B.C.E.). During some of this time they acted as either agents or vassals of Egyptian powers.

The Philistines enjoyed an apparently strong position in relation to their neighbors (including the Israelites) from the twelfth through tenth centuries B.C.E. In the tenth century, they possessed iron weapons and chariots, while the Israelites had developed no comparable technology. During the reigns of Saul and David, the Philistines were able to raid and sometimes occupy Israelite towns as far east as the Jordan River valley, while their own fortified towns remained secure from counter-attack. Also, the site of Gath has now been identified with Tell es-Safi in central Israel, which would make the actual Philistine territory considerably larger than usually indicated on biblically-based maps, which tend to accept biblical claims regarding borders.

Although their origins were elsewhere, the Philistines seem to have adopted Canaanite religion to a great degree, including some aspects of the religion of the Israelites. As stated in 1 Kings 5:2: "And the Philistines took the ark of God, and brought it into the temple of Dagon, and set it by Dagon." Moreover, several Philistine kings are represented in the Bible as making oaths in the name of the Israelite God. The character of Dagon himself is debated. Many consider him to have been a Semitic fertility deity similar to (Baal)-Hadad. Some scholars, however, believe that Dagon was a type of fish-god (the Semitic word dag meaning "little fish"), consistent with the Philistines as a sea-faring people. References to worship of the goddess Ishtar/Astarte are also evident (1 Sam. 31:10).

Philistine independence, like that of the northern Kingdom of Israel, came to an end as a result of invasion by the Assyrian Empire in the eighth century B.C.E. Babylonian domination in the seventh century seems to have spelled an end to Philistine civilization altogether, and the Philistines cease to be mentioned by this name. References to the land of the Philistines continue for several centuries, however. Alexander the Great conducted a siege of the city of Gaza, and both the Ptolemies and Seleucids fought over Philistine territory. Eventually the land finally came under Roman rule.

Biblical accounts

Much of the history of the Philistines is derived from accounts in the Bible, where they are portrayed as the enemies of both the Israelites and God. In reading these accounts it is important to recall that they are written from the perspective of the biblical authors, in which Israel, not Philistia, is the key nation.

Genesis and Exodus

The Philistines are described in Genesis as already inhabiting Canaan in the time of Abraham. However, most historians and archaeologists consider these references to be anachronistic. The Book of Exodus mentions, more plausibly, that during the time of Moses, the Hebrews did not enter Canaan by "the Way of the Philistines" because God believed that, "If they face war, they might change their minds and return to Egypt" (Exod. 13:17). The Mediterranean Sea is called "the Sea of the Philistines" in Exodus 23:31.

Joshua and Judges

Joshua 13:2 lists the Philistine city-states as among the lands which Joshua was supposed take over, but had yet to conquer. However, Judges 3:1-3 lists these same territories as having been left untaken by God's will in order to "test" the Israelites.

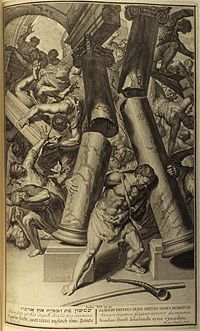

The Bible describes an ebb-and-flow struggle between the Philistines and Israelites particularly in the Book of Judges and the Books of Samuel. The judge Shamgar reportedly killed six hundred Philistines with an oxgoad. However, Judges 10 reports that the Israelites later became vassals of the Philistines and worshiped their gods. The judge Samson (Judges 14-16) himself intermarried with a Philistine woman, spent the night with a prostitute in Gath, and fell in love the Philistine beauty, Delilah.

During this period the tribe of Judah was allied with the Philistines and helped them attempt to capture Samson. In his adventures, Samson reportedly killed several thousand Philistines but did not liberate any Israelite tribe from Philistine rule. From the Samson account we also learn that the Philistines worshiped Dagon. The bible preserves a brief victory hymn sung in honor of Dagon after the capture of Samson:

- Our God has delivered our enemy

- into our hands,

- the one who laid waste our land

- and multiplied our slain. (Judges 16:24)

During the judgeship of Eli, the Philistines won a major victory at the Battle of Ebenezer in which they slew the Israelite tabernacle priests Hophni and Phinehas and captured the Ark of the Covenant (1 Sam. 4). Later rabbinical tradition gives the primary credit for this victory to the mighty Philistine warrior Goliath of Gath. The ark was soon returned to the Israelites after the Philistines came to believe it had brought them bad fortune.

Samuel, Saul and David

About two decades later, the Philistine army suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Mizpah as a result of the leadership of the great judge Samuel. The Bible declares that "the Philistines were subdued and did not invade Israelite territory again." (1 Sam. 7:13) However, the Philistine confederation continued to dominate the Israelite tribes to a significant degree. When Yahweh told Samuel to appoint Saul as Israel's first king (1 Sam. 9), he commanded: "Anoint him leader over my people Israel; he will deliver my people from the hand of the Philistines." A Philistine military outpost is mentioned as being located deep in Israelite territory near the town of Gibeah. (1 Samuel 10:5) Another, located at Geba, was successfully attacked by Jonathan and Saul. After this, the Philistines assembled a major force (reportedly including three thousand chariots) at Micmash to punish this rebellion.

In this account we are told that the Philistines held a monopoly on iron smithing (a skill they possibly acquired during conquests in Anatolia) and that the Israelites were totally dependent on them for the manufacture and repair of modern weapons. Nevertheless, the Israelites were victorious at Micmash through a combination of surprise tactics and divine aid (1 Sam. 14). The Israelites, however, did not press their temporary advantage, and the biblical declaration "Wherever he (Saul) turned, he inflicted punishment on them," (1 Sam. 14:47) hardly seems credible.

By far the most memorable account of a confrontation between the Israelites and Philistines, of course, is the story of the young Hebrew David and the mighty Goliath of Gath while the two armies are assembled at the Valley of Elah. The story, in which David and Goliath meet as champions in single combat, is a precursor to an Israelite rout of the Philistines, who retreat to Gath. Lost in the story is the fact that Gath, a major Philistine stronghold, was located well into the territory normally thought of as belonging to the tribe of Judah.

War continued to rage between Philistia and Israel with the Bible reporting David as Saul's most effective captain. However, Saul became jealous of David, treating him as a rebel and outlaw. Fearing death at Saul's hands, David hid out in Philistine territory for 16 months together with six hundred armed men. King Achish of Gath offered him protection from Saul, in exchange for David becoming his vassal and attacking Achish's enemies (1 Sam. 27).

The Philistines won a major victory against Israelite forces at the Battle of Gilboa, during which both Saul and his heir Jonathan died. In 1 Sam. 31:7, the Philistines occupied the entire Jordan River valley in the aftermath. A lament attributed to David gives a sense of the demoralization faced by the Israelites after the battle:

- Tell it not in Gath,

- proclaim it not in the streets of Ashkelon,

- lest the daughters of the Philistines be glad,

- lest the daughters of the uncircumcised rejoice.

- O mountains of Gilboa,

- may you have neither dew nor rain,

- nor fields that yield offerings of grain... (2 Sam. 1:20-21)

David, meanwhile, had left Achish's service and was soon recognized as king of Judah. Seven years later, he also became king of Israel. Seeing in this development a serious threat, the Philistines marched against him suffering defeat at Baal Perazim. In a reversal of the earlier Battle of Ebenezer, the Israelites succeeded in capturing several Philistine religious symbols. Using a clever encircling tactic, David pressed the advantage and dealt the Philistines an additional blow, driving them out of several Jordan Valley towns they had previously taken (2 Sam. 5).

The Bible describes the Philistines as remaining "subdued" during David's reign, although there is no indication of David's ever taking Gath, which lay in the territory traditionally ascribed to Judah. Several battles are described in 2 Samuel 21, in which Philistine champions, the giant sons of Rapha, fought against Israel. In one encounter, David "became exhausted" and faced death at the hands of the huge spearman Ishbi-Benob. David's lieutenant Abishai came to the king's rescue, after which David would no longer lead his troops in battle. Three other mighty Philistine soldiers are mentioned by name here, all sons of Rapha. And in this version of the saga, it is not David but one of his captains, Elhanan of Bethlehem, who slew the gigantic Philistine warrior Goliath.

Later biblical accounts

The Bible says little of the Philistines after the time of David, although it should not therefore be presumed that territorial disputes between the Israelites and Philistines had been settled. Centuries later, King Uzziah of Judah (mid-eighth century B.C.E.) reportedly defeated the Philistines at Gath after destroying its wall (2 Chron. 26:7). During the reign of Uzziah's successor, Ahaz, the Philistines were more successful, capturing and occupying "Beth Shemesh, Aijalon and Gederoth, Soco, Timnah and Gimzo, with their surrounding villages" (2 Chron. 28:18). King Hezekiah (late eighth century B.C.E.) is described as defeating the Philistines in battles as far west and south as Gaza. These victories, however, were short-lived, as Hezekiah himself lost every major town in Judah, excepting only Jerusalem, to the advancing armies of Sennacharib of Assyria.

The Philistines themselves lost their independence to Tiglath-Pileser III of Assyria by 732 B.C.E., and revolts in following years were all crushed. Later, Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon conquered all of Syria and the Kingdom of Judah, and the former Philistine cities became part of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Jeremiah 47 is a prophecy against the Philistines dealing with an attack against Philistia by Egypt, possibly during this period.

Origin of the Philistines

Most authorities agree that the Philistines did not originate in the regions of Israel/Palestine which the Bible describes them inhabiting. One reason for this is that the Bible repeatedly refers to them as "uncircumcised," unlike the Semitic peoples, such as Canaanites (See 1 Sam. 17:26-36; 2 Sam. 1:20; Judg. 14:3).

A prominent theory is that the Philistines formed part of the great naval confederacy, the "Sea Peoples," who had wandered, at the beginning of the twelfth century B.C.E., from their homeland in Crete and the Aegean islands to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, where they repeatedly attacked Egypt during the later nineteenth dynasty. They were eventually defeated by Ramses III, and he then resettled them, according to the theory, to rebuild the coastal towns in Canaan.

Archaeology

Papyrus Harris I details the achievements of the reign of Ramses III. In the brief description of the outcome of the battles in eight year of Ramses' reign is the description of the fate of the Sea Peoples. Ramses tells us that, having brought the imprisoned Sea Peoples to Egypt, he "settled them in strongholds, bound in my name. Numerous were their classes like hundred-thousands. I taxed them all, in clothing and grain from the storehouses and granaries each year." Some scholars suggest it is likely that these "strongholds" were fortified towns in southern Canaan, which would eventually become the five cities (the Pentapolis) of the Philistines/[2]

The connection between Mycenaean culture and Philistine culture was made clearer by finds at the excavation of Ashdod, Ekron, Ashkelon, and more recently Tell es-Safi (probably Gath), four of the five Philistine cities in Canaan. The fifth city is Gaza. Especially notable is the early Philistine pottery, a locally-made version of the Aegean Mycenaean Late Helladic IIIC pottery, which is decorated in shades of brown and black. This later developed into the distinctive Philistine pottery of the Iron Age I, with black and red decorations on white slip. Also of particular interest is a large, well-constructed building covering 240 square meters, discovered at Ekron. Its walls are broad, designed to support a second story, and its wide, elaborate entrance leads to a large hall, partly covered with a roof supported on a row of columns. In the floor of the hall is a circular hearth paved with pebbles, as is typical in Mycenaean buildings; other unusual architectural features are paved benches and podiums. Among the finds are three small bronze wheels with eight spokes. Such wheels are known to have been used for portable cultic stands in the Aegean region during this period, and it is therefore assumed that this building served cultic functions. Further evidence concerns an inscription in Gath to PYGN or PYTN, which some have suggested refers to "Potnia," the title given to an ancient Mycenaean goddess. Excavations in Ashkelon and Ekron reveal dog and pig bones which show signs of having been butchered, implying that these animals were part of the residents' diet.

Philistine language

There is some limited evidence in favor of the assumption that the Philistines did originally speak some Indo-European language. A number of Philistine-related words found in the Bible are not Semitic, and can in some cases, with reservations, be traced back to Proto-Indo-European roots. For example, the Philistine word for captain, seren, may be related to the Greek word tyrannos (which, however, has not been traced to a PIE root). Some of the Philistine names, such as Goliath, Achish, and Phicol, appear to be of non-Semitic origin, and Indo-European etymologies have been suggested. Recently, an inscription dating to the late tenth/early ninth centuries B.C.E. with two names, very similar to one of the suggested etymologies of the name Goliath (Lydian Alyattes/Wylattes) was found in the excavations at Tell es-Safi. The appearance of additional non-Semitic names in Philistine inscriptions from later stages of the Iron Age is an additional indication of the non-Semitic origins of this group.

One name the Greeks used for the previous inhabitants of Greece and the Aegean was Pelasgians, but no definite connection has been established between this name and that of the Philistines. The theory that the Sea Peoples included Greek-speaking tribes has been developed even further to postulate that the Philistines originated in either western Anatolia or the Greek peninsula.

Statements in the Bible

The Hebrew tradition recorded in Genesis 10:14 states that the "Pelishtim" (◊§◊ú◊©◊™◊ô◊Ě; Standard Hebrew: P…ôliŇ°tim; Tiberian Hebrew: P…ôliŇ°t√ģm) proceeded from the "Patrusim" and the "Casluhim," who descended from Mizraim (Egypt), son of Ham. The Philistines settled Philistia (◊§◊ú◊©◊™; Standard Hebrew: P…ôl√©Ň°et / P…ôl√°Ň°et; Tiberian Hebrew: P…ôl√©Ň°eŠĻĮ / P…ôlńĀŇ°eŠĻĮ) along the eastern Mediterranean coast at about the time when the Israelites settled in the Judean highlands. Biblical references to Philistines living in the area before this, at the time of Abraham or Isaac (Gen. 21:32-34), are generally regarded by modern scholars to be anachronisms.

The Philistines are spoken of in the Book of Amos as originating in Caphtor: "saith the Lord: Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt? and the Philistines from Caphtor, and Aram from Kir?" (Amos 9:7). Later, in the seventh century B.C.E., Jeremiah makes the same association with Caphtor: "For the Lord will spoil the Philistines, the remnant of the country of Caphtor‚ÄĚ (Jer. 47:4). Scholars variously identify the land of Caphtor with Cyprus and Crete and other locations in the eastern Mediterranean.

Critics have also noted a number of anachronistic references to the Philistines in the Bible. Genesis refers to the Philistines being "in the land" already when Abraham arrived, supposed around the second millennium B.C.E. Both he and Isaac reportedly received protection and rewards from a "Philistine" king called Abimelech of Gerar, after allowing their wives to become part of Abimelech's harem. If indeed the Philistines did not arrive in Canaan until around the twelfth century B.C.E., then references to their presence during the time of Abraham and Isaac are out of place.

Footnotes

- ‚ÜĎ Michele MacLaren, Liam McManus, and Megaera Lorenz. The Inscriptions of Medinet Habu: Texts from the Medinet Habu Temple with Reference to the Sea Peoples. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Donald Bruce Redford, 1992, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691000862), p. 289.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dothan, Trude Krakauer, and Moshe Dothan. 1992. People of the Sea: The Search for the Philistines. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0025322615

- Easton, Matthew George. 1897. Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 3rd Edition. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- Gitin, Seymour, Amihai Mazar, and Ephraim Stern (eds.). 1998. Mediterranean Peoples in Transition: Thirteenth to Early Tenth Centuries B.C.E. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Mendenhall, George E. 1971. The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801816543

- Redford, Donald Bruce. 1992. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691000862

External links

All links retrieved November 23, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.