Jericho

Jericho (Arabic أرÙØا, ʼArīḥÄ; Hebrew ×ְרִ×××Ö¹, Standard YÉriḥo Tiberian YÉrîḫô / YÉrîḥô; meaning "fragrant,"[1] Greek ἹεÏιÏÏ = ἹεÏή á¼ ÏÏ, HierÄ ÄchÅ (Holy echo) is a town in the West Bank, Palestine near the Jordan River. The history of Jericho goes back to the end of pre-history and to the beginning of human culture, when a more settled and secure life allowed humans to devote time for art, craft, and even more sophisticated religious ritual.

There is debate among Christian and secular scholars about whether the archeological record confirms the Biblical story of the Battle of Jericho. The archeological record does, however, tell much of the story of human development. Beginning from the earliest settlement when the population lived in pits during the early Neolithic Age, through to the construction of huts in the later Neolithic period, and on through to the first fortification of the city around about 2900 B.C.E. The city continued as an important trading post and stopping point on the journey through the Jordan valley and remains a viable commercial center and a market town for local agricultural products such as dates, citrus fruits, and barley. Its history has seen various populations living and ruling there, such as the Hyksos, or Shepherd Kings (1750â1580 B.C.E.), the Canaanites who, according to the Bible, were conquered by Joshua and the Hebrews and, after the seventh century, by Muslim Arabs.

Recent history

The present city was captured by Israel after the Six-Day War in 1967. It was the first city handed over to Palestinian Authority control in 1994, in accordance with the Oslo accords. After a period of Israeli re-administration, it was returned to the Palestinian Authority on March 16, 2005.

Jericho prison incident

On March 14, 2006, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) took captive six inmates from a Jericho prison following a ten-hour siege. The IDF said the reason for taking the prisoners, who were wanted for participation in the assassination of Israeli tourism minister Rehavam Zeevi, was to keep them from being released. Both sides of the siege were armed and at least two people were killed and 35 wounded in the incident.

Synagogue

An ancient synagogue was discovered in Jericho in 1936. It has been controlled by Israel since the Six-Day War, but after the Oslo Accords and especially the Al Aqsa Intifada, it has been a source of conflict.

Archaeology

Three separate settlements have existed at or near the current location for more than eleven thousand years. The position is on an east-west route north of the Dead Sea.

The first archaeological excavations of the site were made by Charles Warren in 1868. Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzinger excavated Tell es-Sultan and Tulul Abu el-'Alayiq between 1907 and 1909 and again in 1911. John Garstang excavated between 1930 and 1936. Extensive investigations using more modern techniques were made by Kathleen Kenyon between 1952 and 1958. Lorenzo Nigro and Nicolo Marchetti conducted a limited excavation in 1997. Later that same year, Dr. Bryant Wood also made a visit to the site to verify the findings of the earlier 1997 team.

Tell es-Sultan

The earliest settlement was located at the present-day Tell es-Sultan (or Tell Sultan), about a mile and a half from the current city. In Arabic, tell means "mound"âconsecutive layers of habitation built up a mound over time, as is common for ancient settlements in the Middle East and Anatolia. Jericho is the type site of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPN A) and B.

The habitation has been classed into several phases:

Natufian

Epipaleolithicâconstruction at the site apparently began before the invention of agriculture, with construction of the stone structures of the Natufian culture beginning earlier than 9000 B.C.E.

PPN A

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (8350 B.C.E.â7370 B.C.E.) Sometimes it is called Sultanian. The 45,000 square yard settlement is surrounded by a stone wall with a stone tower in the center of one side of the wall. This is so far the oldest wall ever to be discovered, thus suggesting some kind of social organization, even if based on charisma. The town contained round, mud-brick houses, but no street planning. The population of approximately two thousand people used domesticated emmer wheat, barley, and pulses and hunted wild animals.

PPN B

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (7220 B.C.E.â5850 B.C.E.) An expanded range of domesticated plants was created in this period as well as the possible domestication of sheep. There is also evidence pointing to certain cult practices involving the preservation of human skulls, with facial features reconstructed from plaster and eyes set with shells in some cases.

After the PPN A settlement-phase there was a settlement hiatus of several centuries. Then the PPN B settlement was founded on the eroded surface of the tell. The architecture consisted of rectilinear buildings made of mud-bricks on stone foundations. The mud-bricks were loaf-shaped with deep thumb prints to facilitate bounding. No building has been excavated in its entirety. Normally, several rooms cluster around a central courtyard. There is one big room (6.5 x 4 m and 7 x 3 m) with internal divisions. The rest are small, presumably used for storage. The rooms have red or pinkish terrazzo floors made of lime. Some impressions of mats made of reeds or rushes have been preserved. The courtyards have clay floors.

Kathleen Kenyon interpreted one building as a shrine. It contained a niche in the wall. A chipped pillar of volcanic stone that was found nearby might have fit into this niche.

The dead were buried under the floors or in the rubble fill of abandoned buildings. There are several collective burials and not all the skeletons are completely articulated, which may point to a time of exposure before burial. A skull cache contained seven skulls. The jaws were removed, the face covered with plaster, cowries were used for eyes. Ten skulls were found in all. Modeled skulls were found in Tell Ramad and Beisamoun as well.

Other finds

- Flints: arrowheads (tanged or side-notched), finely denticulated sickle-blades, burins, scrapers, a few tranchet axes. One percent obsidian, Ciftlik, and green obsidian from unknown source

- Ground stone: querns, hammerstones, a few ground-stone axes made of greenstone. Dishes and bowls carved from soft limestone. Spindle whorls made of stone and maybe loom weights

- Bone Tools: Spatulas and drills

- Stylized anthropomorphic plaster figures, almost life-size

- Anthropomorphic and theriomorphic clay figurines

- Shell and malachite beads

Pottery Neolithic A and B

Late fourth millennium B.C.E.. Jericho was occupied during Neolithic 2 and the general character of the remains on the site link it culturally with Neolithic 2 sites in the West Syrian and Middle Euphrates groups. There are the rectilinear mud-brick buildings and plaster floors.

Bronze age

Walls of Jericho

The Biblical account of the destruction of Jericho is found in the Book of Joshua. The Bible describes the destruction as having proceeded from the actions of Joshua, Moses' successor. The exodus is usually dated to the thirteenth century B.C.E. (based on Ussherian calculation) according to interpretation of archeological evidence from the Merneptah Stele, followed by new settlements in the next century. At that time fifteenth century B.C.E. according to a prevailing Christian reckoning of biblical chronology, which is synchronized with several ancient calendars with astronomical observation. At that time the pharaoh would be Thutmose III (1490-1430B.C.E.). Neither biblical chronology matches the popular interpretation of the archeological evidence at Jericho.

A destruction of Jericho's walls dates archeologically to around 1550 B.C.E., at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, by a siege or an earthquake in the context of a burn layer, called City IV destruction. Opinions differ as to whether they are the walls referred to in the Bible. According to one biblical chronology, the Israelites destroyed Jericho at the end of the fifteenth century, after its walls had fallen around 1407 B.C.E. Originally, John Garstang's excavation in the 1930s dated Jericho's destruction to around 1400 B.C.E., but like much early biblical archaeologists, he was criticized for using the Bible to interpret the evidence rather than the hard facts on the ground. Kathleen Kenyon's excavation in the 1950s re-dated the fall of the walls to around 1550 B.C.E., a date that most archeologists support.[2][3] In 1990, Bryant Wood critiqued Kenyon's work after her field notes became fully available. Observing ambiguities and relying on the only available carbon dating of the burn layer, which yielded a date of 1410 B.C.E. plus or minus 40 years, Wood dated the destruction to this carbon dating, confirming Garstang and the biblical chronology. Unfortunately, this carbon date was itself the result of faulty calibration. In 1995, Hendrik J. Bruins and Johannes van der Plicht used high-precision radiocarbon dating for 18 samples from Jericho, including six samples of charred cereal grains from the burn layer, and overall dated the destruction to 1562 B.C.E. plus or minus 38 years.[4][5] Kenyon's date of around 1550 B.C.E. is more secure than ever. Notably, many other Canaanite cities were destroyed around this time.

Scholars who link these walls to the biblical account must explain how the Israelites arrived around 1550 B.C.E., but settled four centuries later. They must also devise a new biblical chronology that corresponds. The current opinion of many archaeologists is in stark contradiction to the biblical account.

The widespread destructions of the sixteenth century B.C.E. are often linked with the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt around this time. Interestingly, the first-century historian Josephus, in Against Apion, identified the Exodus of Israelites according to the Bible as the Expulsion of the Hyksos according to the Egyptian texts. Nevertheless, Josephus's historical inaccuracies should be considered and his word not taken as law.

A few scholars follow the controversial new chronology of David Rohl, which postulates that the entire mainstream Egyptian chronology is three hundred years misplaced; therefore, the exodus would be dated to the sixteenth or seventeenth century B.C.E., and the archaeological record on Jericho would be much more aligned with the biblical account. Despite this, a number of literalist Christians, most prominently the respected Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen, have vehemently attacked Rohl's chronology, since it introduces a number of other problems and issues (such as identifying the biblical Shishak as Ramses II, rather than the far more obviously named Shoshenq).

Tulul Abu el-'Alayiq

A later settlement spanned the Hellenistic, New Testament, and Islamic periods, leaving mounds located at Tulul Abu el-'Alayiq, approximately one and a half miles west of modern er-Riha. It is suspected that this settlement was very violent.

Biblical references

Jericho is mentioned in the Jewish Hebrew Bible (the Christian Old Testament), over 70 times. Here are some examples:

- Prior to Moses's death, God is said to have shown him the Promised Land in the Book of Deuteronomy with Jericho as a point of reference: "And Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto mount Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, that is over against Jericho. And the Lord showed him all the land, even Gilead as far as Dan."[6]

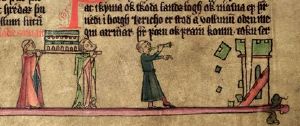

- The Book of Joshua describes the famous siege of Jericho, claiming that it was circled seven times by the ancient Children of Israel until its walls came tumbling down, after which Joshua cursed the city: "And Joshua charged the people with an oath at that time, saying: 'Cursed be the man before the Lord that riseth up and buildeth this city, even Jericho, with the loss of his first-born shall he lay the foundation thereof, and with the loss of his youngest son shall he set up the gates of it'."[7]

- The Book of Jeremiah describes the end of the Judean king Zedekiah when he is captured in the area of Jericho: "But the army of the Chaldeans pursued after them, and overtook Zedekiah in the plains of Jericho; and when they had taken him, they brought him up to Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon to Riblah in the land of Hamath, and he gave judgment upon him."[8]

Notes

- â The HTML Bible, Strong's Bible Dictionary Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- â Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (Free Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0684869124).

- â Matthew Sturgis, It Ain't Necessarily So: Investigating the Truth of the Biblical Past (Headline, 2001, ISBN 978-0747245063).

- â Gerald E. Aardsma, Wood's Jericho Tumbles The Biblical Chronologist 2(3) (1996). Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- â Let the Stones Speak Daylight Atheism. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- â Deuteronomy 34:1 Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- â Joshua 6:26 Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- â Jeremiah 39:5 Retrieved November 10, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bartlett, John R. Jericho: Cities of the Biblical World. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1983. ISBN 0802810330

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Free Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0684869124

- Kenyon, Kathleen. Digging Up Jericho. New York: Praeger, 1957.

- Scheller, William Amazing Archaeologists and Their Finds, Minneapolis, MN: Oliver Press, 1994. ISBN 9781881508175

- Sturgis, Matthew. It Ain't Necessarily So: Investigating the Truth of the Biblical Past. Headline, 2001. ISBN 978-0747245063

External links

All links retrieved December 23, 2024.

- Ancient Jericho (Tell Sultan) The History of the Ancient Near East Electronic Compendium.

- Early Jericho Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- Why Do People Build Walls? The Real Story of Jericho Offers a Surprising Answer TIME, May 30, 2019.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.