Aristobulus II

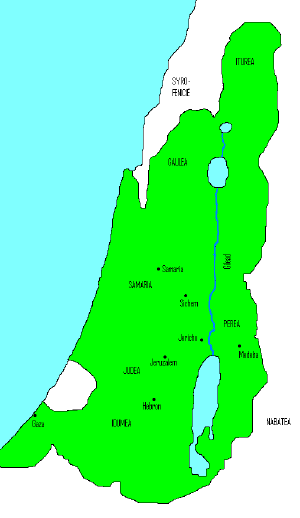

Aristobulus II (100 - 49 B.C.E.) was the Jewish king and high priest of Judea from 66 to 63 B.C.E. His reign brought an end to the independent Jewish state and marked the beginning of Roman rule over the Jews.

A member of the the Hasmonean dynasty, he was the younger son of Alexander Jannaeus, but not his heir or immediate successor. A supporter of the Sadducees, Aristobulus seized the throne from his older brother, Hyrcanus II, following the death of their mother, Alexandra Salome, who had ruled as queen after her husband, Alexander's, death.

A civil war soon followed, and eventually the power of Rome, led by its formidable general Pompey, was brought to bear on the situation. The tragic result was the demise of the Jewish state and the establishment of Roman sovereignty over Jerusalem and Judea. In the aftermath, client kings such as Herod the Great, or governors such as Pontius Pilate, ruled the Jews on behalf of Rome until the Jews were driven out of Jerusalem and its environs after a series of revolts in the first and second centuries C.E.

Background

The early Hasmoneans were seen as heroes for successfully resisting the oppression of the Seleucids and founding the first independent Jewish kingdom since Jerusalem had fallen to Babylonians in the sixth century B.C.E. However, religious Jews tended to believe that the Hasmoneans lacked legitimacy since they were not descended from the Davidic line. Some also viewed the Hasmoneans as worldly, overly concerned with money and military power. The hope of a Messiah, the "son of David," grew ever stronger in tension with the corrupt reality of Hasmonean rule.

Meanwhile, the Sadducees emerged as the party of the priests and the Hasmonean elites, taking their name, Sadducee, from King Solomon's loyal priest, Zadok. Their rivals, the Pharisees, emerged out of the group of scribes and sages who objected to the Hasmonean monopoly on power, hoped for a Messiah, and criticized the growing corruption of the Hasmonean court.

During the Hasmonean period, the Sadducees and Pharisees functioned primarily as political parties. According to Josephus, the Pharisees opposed the Hasmonean war against the Samaritans, as well as the forced conversion of the Idumeans. The political rift between the two parties grew wider under the Hasmonean king, Alexander Jannaeus, who adopted Sadduceean rites in the Temple.

Family

Alexander Jannaeus acted as both king and high priest, and Aristobulus was his younger son. His mother was Alexandra Salome. After the death of Alexander in 79 B.C.E., Alexandra succeeded to the rule of Judea as its queen. She installed her elder son Hyrcanus II as high priest. Unlike his father, Hyrcanus was favorably inclined to the Pharisees. When Salome died in 67 B.C.E., Hyrcanus rose to the kingship as well.

As the younger son, Aristobulus could not rightfully claim the throne. However, he apparently desired the kingship, even during the life of his mother. He courted the nobles by acting as the patron of the Sadducees and bringing their cause before the queen. She is reported to have placed several fortresses at their disposal. Aristoblus' encouragement of her in this may have been one his preparatory moves for his plan to usurp the government.

The queen sought to direct Aristobulus' military zeal outside of Judea. When this undertaking failed, Aristobulus resumed his political intrigues closer to home. He left Jerusalem secretly and conspired with his Sadducean allies with the intention of making war against his aged mother. However, the queen died at the critical moment, and Aristobulus immediately turned his weapons against his brother Hyrcanus, the legitimate heir to the throne.

Hyrcanus advanced against Aristobulus, and the brothers met in battle near Jericho. However, many of Hyrcanus' soldiers went over to Aristobulus, thereby providing the means to victory. Hyrcanus took refuge in the citadel of Jerusalem, but the capture of the Temple by Aristobulus compelled Hyrcanus to surrender. A peace was then concluded. According to the terms of of the agreement, Hyrcanus was to renounce both the throne and the high priesthood, but was allowed to benefit from the revenues of the priestly office. Hyrcanus' reign had lasted only three months.

This agreement, however, did not last, as Hyrcanus feared that Aristobulus was planning his death. Antipater the Idumean, who had been military commander under Alexander Jannaeus, continued to support Hyrcanus. He advised Hyrcanus to put himself under the protection of the Arabian (Nabataean) king Aretas III in Petra. Together with their new allies, the Nabataeans advanced toward Jerusalem with an army of 50,000. The Phariseesâthe most powerful party in Jerusalemâthrew in their lot with Hyrcanus, and Aristobulus was compelled to withdraw to the Temple Mount. Hyrcanus, Antipater, and the Nabataeans besieged the city for several months.

Roman intervention

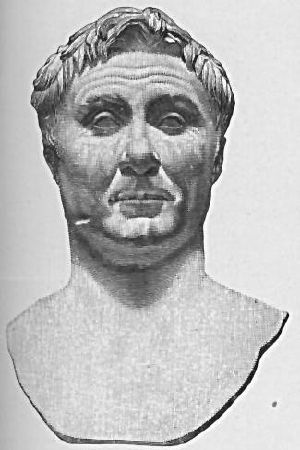

With the siege inconclusive, a third partyâRomeâwas called in to unravel the complicated situation. The effects of this intercession proved not only injurious to the brothers, but in the end brought about the destruction of the Jewish state. At that time (65 B.C.E.) Pompey had already brought nearly the whole of the East under subjugation. He had sent his legate, Scaurus, to Syria, to take possession of the heritage of the Seleucids. Ambassadors from both the Judean parties presented themselves to Scaurus, requesting his assistance.

A bribe of 400 talents from Aristobulus turned the scale in his favor. Aretas was commanded to abandon the siege of the Temple Mount. Aristobulus was thus victorious, and Hyrcanus retained only an insignificant portion of his power. Aristobulus also had the satisfaction of avenging himself upon Aretas. As the Arabian was withdrawing with his forces from Jerusalem, Aristobulus followed and inflicted severe losses upon him.

However, the Romans, to whom he had looked with so much confidence, soon became a factor which worked most detrimentally against Aristobulus. A magnificent golden vine, valued at 500 talents, which Aristobulus presented to Pompeyâand which excited the admiration of the Romans even in later generationsâhad no effect upon him.

In the year 63, the still hostile brothers appeared before Pompey, as did delegates of a third group, which desired the complete abolition of the Hasmonean dynasty. Pompey refused to give any immediate decision. He apparently contemplated the end of Jewish independence from Rome, and Aristobulus saw through the aims of the Roman general. Although powerless to offer effective resistance, his pride did not permit him to yield without a show of opposition. He left Pompey in a burst of indignation, and entrenched himself at the citadel of Alexandrion. Pompey pursued him and demanded the complete surrender of all the forts controlled by Arisobulus' forces. Aristobulus capitulated, but immediately proceeded to Jerusalem to prepare himself for resistance there. However, when he saw that Pompey pressed on against him, his courage failed him. He came to the general's camp, promising both gold and the surrender of Jerusalem if hostilities were suspended.

Pompey detained Aristobulus in the camp and sent his captain, Gabinius, to take possession of the city. The war party in Jerusalem refused to surrender, and Aristobulus was made prisoner by Pompey, who proceeded to besiege the capital. His eventual capture of Jerusalem and of the Temple Mount ended the independence of Judea as well as the reign of Aristobulus. In the triumph celebrated by Pompey in Rome (61 B.C.E.), Aristobulus, the Jewish king and high priest, was compelled to march in front of the chariot of the conqueror.

The Pharisees saw in this circumstance a just punishment for Aristobulus' support of the Sadducees. But an even more severe fate was in store for him. In the year 56, he succeeded in escaping from prison in Rome. Proceeding to Judea, he stirred up a revolt against Rome rule. He was recaptured, however, and again taken to Rome. Then, in 49, he was liberated by Caesar and sent at the head of two legions against Pompey in Syria, but on his way there, he was poisoned, though not fatally, by Pompey's allies. Aristobulus was carried captive to Rome, where he was assassinated.

Hyrcanus, meanwhile, was restored to his position as the high priest, but not to the kingship. Political authority rested with the Romans, and their interests were represented by Antipater, whose second son would be Herod the Great. In 47 B.C.E., Julius Caesar restored some political authority to Hyrcanus by appointing him "ethnarch." This, however, had little practical effect, since Hyrcanus yielded to Antipater in everything.

Aristobulus' son, Antigonus, led a rebellion against Rome 40 B.C.E., but was defeated and killed in the year 37.

Legacy

Aristobulus' machinationsâfirst against his mother, then against his brother, and finally against mighty Romeâbrought an end to the independent state which the Jews had won at such a great price during the Maccabean revolt. Client kings and Roman governors would rule the Jews henceforth, until a new revolt brought about the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 C.E., marking the beginning of the great Jewish diaspora.

The best known character in the aftermath of Aristobulus' career would be the son of his military rival Antipater, namely Herod the Great. The tragedy of Aristobulus, a supporter of the Sadduceean nobility, also paved the war for the rise of the Pharisees not merely as a political party but as a key religious force, leading ultimately to the rabbinical tradition in Judaism. The vacuum left by the demise of the independent Hasmonean kings also gave rise to increasing messianic hopes, leading up to such famous messianic figures as Jesus of Nazareth and Simon Bar Kochba.

| House of Hasmoneus Died: 37 B.C.E. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Hyrcanus II |

King of Judaea 66 B.C.E. â 63 B.C.E. |

Succeeded by: Hyrcanus II |

| High Priest of Judaea 66 B.C.E.â63 B.C.E. | ||

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Efron, Joshua. Studies on the Hasmonean Period. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1987. ISBN 9789004076099.

- Horbury, William, Markus N. A. Bockmuehl, and James Carleton Paget. Redemption and Resistance: The Messianic Hopes of Jews and Christians in Antiquity. London: T&T Clark, 2007. ISBN 9780567030436.

- Margulis, Bonnie. The Queenship of Alexandra Salome: Her Role in the Hasmonean Dynasty, Her Achievements and Her Place in History. Thesis (Rabbinic)âHebrew Union CollegeâJewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, 1992.

- Tomasino, Anthony J. Judaism Before Jesus: The Events and Ideas That Shaped the New Testament World. Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 2003. ISBN 9780851117874.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.