Difference between revisions of "Capital punishment" - New World Encyclopedia

(copied from Wikipedia) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (65 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Law]] | [[Category:Law]] | ||

| + | {{Copyedited}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Francisco de Goya y Lucientes 023.jpg|thumb|right|300px|''Executions of the Third of May'' by [[Francisco Goya]]]] | ||

| + | '''Capital punishment''', or the '''death penalty''', is the execution of a convicted criminal by the state as [[punishment]] for the most serious [[crime]]s—known as ''capital crimes''. The word "capital" is derived from the [[Latin]] ''capitalis'', which means "concerning the head"; therefore, to be subjected to capital punishment means (figuratively) to lose one's head. The death penalty when meted out according to [[law]] is quite different from [[murder]], which is committed by individuals for personal ends. Nevertheless, human life has supreme value. Regimes that make prolific use of capital punishment, especially for [[politics|political]] or [[religion|religious]] offenses, violate the most important [[human rights|human right]]—the right to life. | ||

| − | + | The death penalty was historically misused, meted out for minor [[crime]]s, and to suppress political dissent and religious minorities. Such misuse of the death penalty greatly declined in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and today it has been abolished in many countries, particularly in [[Europe]] and [[Latin America]]. In most countries where it is retained, it is reserved as a punishment for only the most serious crimes: premeditated [[murder]], [[espionage]], [[treason]], and in some countries, [[drug trafficking]]. Among some countries, however, use of the death penalty is still common. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Capital punishment remains a contentious issue, even where its use is limited to punishment of only the most serious crimes. Supporters argue that it deters crime, prevents [[recidivism]], and is an appropriate punishment for the crime of murder. Opponents argue that it does not deter criminals more than would life imprisonment, that it violates [[human rights]], and runs the risk of executing some who are wrongfully convicted, particularly minorities and the poor. Punishment that allows criminals to reflect and reform themselves is arguably more appropriate than execution. Yet, in the ideal society, human beings should be able to recognize, based on their own [[conscience]], that crimes deemed serious enough to merit the death penalty or life imprisonment constitute undesirable, unacceptable behavior. | ||

| − | + | == History == | |

| + | Even before there were historical records, [[tribalism|tribal societies]] enforced [[justice]] by the principle of ''[[lex talionis]]'': "an eye for an eye, a life for a life." Thus, death was the appropriate punishment for [[murder]]. The biblical expression of this principle (Exod. 21:24) is understood by modern scholars to be a legal formula to guide judges in imposing the appropriate sentence. However, it hearkens back to tribal society, where it was understood to be the responsibility of the victim's relatives to exact vengeance upon the perpetrator or a member of his [[family]]. The person executed did not have to be an original perpetrator of the [[crime]] because the system was based on tribes, not individuals. This form of justice was common before the emergence of an arbitration system based on the state or organized [[religion]]. Such acts of retaliation established rough justice within the social collective and demonstrated to all that injury to persons or property would not go unpunished. | ||

| − | + | Revenge killings are still accepted legal practice in [[tribe|tribally]]-organized societies, for example in the [[Middle East]] and [[Africa]], surviving alongside more advanced [[legal system]]s. However, when it is not well arbitrated by the tribal authorities, or when the murder and act of revenge cross tribal boundaries, a revenge killing for a single crime can provoke retaliation and escalate into a blood feud, or even a low-level [[war]] of vendetta (as in contemporary [[Iraq]] or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict). | |

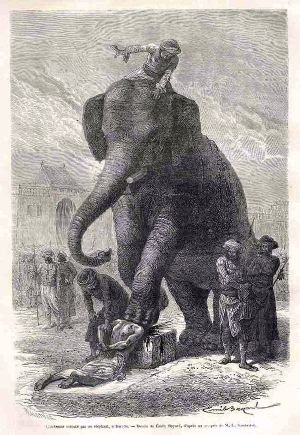

| − | + | [[Image:Le Toru Du MOnde.jpg|right|thumb|[[Crushing by elephant]]]] | |

| + | Compared to revenge killings, use of formal executions by a strong governing authority was a small step forward. The death penalty was authorized in the most ancient written law codes. For example, the [[Code of Hammurabi]] (c. 1800 B.C.E.) set different [[punishment]]s and compensation according to the different class/group of victims and perpetrators. The [[Hebrew Bible]] laid down the death penalty for [[murder]], [[kidnapping]], [[magic]], violation of the [[Sabbath]], [[blasphemy]], and a wide range of [[sexual crime]]s, although evidence suggests that actual executions were rare.<ref>William Schabas, ''The Abolition of the Death Penalty in International Law'' (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 052181491X).</ref> | ||

| − | + | Nevertheless, with the expansion of state power, the death penalty came to be used more frequently as a means to enforce that power. In [[ancient Greece]], the [[Athens|Athenian]] legal system was first written down by [[Draco]] in about 621 B.C.E.; there the death penalty was applied for a particularly wide range of crimes. The word "draconian" derives from Draco's laws. Similarly, in medieval and early modern [[Europe]], the death penalty was also used as a generalized form of punishment. In eighteenth-century [[United Kingdom|Britain]], there were 222 crimes which were punishable by death, including crimes such as cutting down a tree or stealing an animal. Almost invariably, however, sentences of death for property crimes were commuted to transportation to a [[penal colony]] or to a place where the felon worked as an indentured servant.<ref>[http://teacher.deathpenaltyinfo.msu.edu/c/about/history/history.PDF "Death Penalty,"] Michigan State University and Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The emergence of modern [[democracy|democracies]] brought with it the concepts of natural rights and equal [[justice]] for all citizens. At the same time there were religious developments within [[Christianity]] that elevated the value of every human being as a child of God. In the nineteenth century came the movement to reform the [[prison]] system and establish "penitentiaries" where convicts could be reformed into good citizens. These developments made the death penalty seem excessive and increasingly unnecessary as a deterrent for the prevention of minor crimes such as theft. As well, in countries like Britain, [[law enforcement]] officials became alarmed when juries tended to acquit non-violent felons rather than risk a conviction that could result in execution. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | [[ | + | The world wars in the twentieth century entailed massive loss of life, not only in combat, but also by summary executions of enemy combatants. Moreover, authoritarian states—those with [[fascism|fascist]] or [[communism|communist]] governments—employed the death penalty as a means of political oppression. In the [[Soviet Union]], [[Nazism|Nazi]] Germany, and in Communist [[China]], millions of civilians were executed by the state apparatus. In [[Latin America]], tens of thousands of people were rounded up and executed by the military in their counterinsurgency campaigns. Partly as a response to these excesses, civil organizations have increasingly emphasized the securing of human rights and abolition of the death penalty. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ===Methods of execution=== | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[image:chair.jpg|right|thumb|[[Electric chair]] as used for electrocutions. The electric chair was developed in the late 1880s by a dentist with support from [[Thomas Edison]] (who had a financial interest in having direct current used in providing electricity, whereas the electric chair uses alternating current) and is still in use today.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Methods of execution have varied over time, and include: | |

| + | * Burning, especially for religious [[heresy|heretics]] and [[witch]]es, at the stake | ||

| + | * Burial alive (also known as "the pit") | ||

| + | * [[Crucifixion]] | ||

| + | * [[Crushing by elephant]] or a weight | ||

| + | * [[Beheading|Decapitation]] or beheading (as by sword, axe, or [[guillotine]]) | ||

| + | * [[Drawing and quartering]] (Considered by many to be the cruelest of punishments) | ||

| + | * [[Electric chair]] | ||

| + | * [[Gas chamber]] | ||

| + | * [[Hanging]] | ||

| + | * Impalement | ||

| + | * [[Lethal injection]] | ||

| + | * [[Poison]]ing (as in the execution of [[Socrates]]) | ||

| + | * Shooting by firing squad (common for military executions) | ||

| + | * Shooting by a single shooter (performed on a kneeling prisoner, as in [[China]]) | ||

| + | * Stoning | ||

| − | === | + | ===Movements towards "humane" execution=== |

| − | + | [[Image:DrGuillotin.jpg|thumb|100px|right|Dr. Guillotin]] | |

| + | The trend has been to move to less painful, or more "humane" methods of capital punishment. [[France]] at the end of the eighteenth century adopted the [[guillotine]] for this reason. Britain in the early nineteenth century banned [[drawing and quartering]]. [[Hanging]] by turning the victim off a ladder or by dangling him from the back of a moving cart, which causes a slow death by suffocation, was replaced by hanging where the subject is dropped a longer distance to dislocate the neck and sever the spinal cord. In the United States the [[electric chair]] and the [[gas chamber]] were introduced as more humane alternatives to hanging; and these have since been superseded by [[lethal injection]], which subsequently was criticized as being too painful. | ||

| + | <br clear="all"> | ||

| − | + | == The death penalty worldwide == | |

| − | + | At one time capital punishment was used in almost every part of the globe; but in the latter decades of the twentieth century many countries abolished it. In [[China]] serious cases of corruption are still punished by the death penalty. In some [[Islam]]ic countries, sexual [[crime]]s including [[adultery]] and [[sodomy]] carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as [[apostasy]], the formal renunciation of Islam. In times of [[war]] or [[martial law]], even in [[democracy|democracies]], military justice has meted out death sentences for offenses such as cowardice, [[desertion]], insubordination, and [[mutiny]].<ref>[http://www.shotatdawn.org.uk/ "Shot at Dawn: Campaign for Pardons for British and Commonwealth Soldiers Executed in World War I] Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | [[Amnesty International]] classifies countries in four categories. As of 2006, 68 countries still maintained the death penalty in both law and practice. Eight-eight countries had abolished it completely; 11 retained it, but only for crimes committed in exceptional circumstances (such as crimes committed in time of [[war]]). Thirty countries maintain laws permitting capital punishment for serious crimes but allowed it to fall into disuse. Among countries that maintained the death penalty, only seven executed juveniles (under 18). Despite this legal picture, countries may still practice extrajudicial execution sporadically or systematically outside their own formal legal frameworks. | |

| − | + | China performed more than 3,400 executions in 2004, amounting to more than 90 percent of executions worldwide. [[Iran]] performed 159 executions in 2004.<ref>Anne Penketh, "China Leads Death List as Number of Executions Around the World Soars," ''The Independent'' (April 5, 2005).</ref> The [[United States]] performed 60 executions in 2005. [[Texas]] has conducted more executions than any of the other states in the United States that still permit capital punishment, with 370 executions between 1976 and 2006. [[Singapore]] has the highest execution rate per capita, with 70 [[hanging]]s for a population of about four million. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Where the death penalty was widely practiced as a tool of political oppression in poor, undemocratic, and authoritarian states, movements grew strongest to abolish the practice. Abolitionist sentiment was widespread in [[Latin America]] in the 1980s, when democratic governments were replacing authoritarian regimes. Guided by its long history of [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]] and [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] thought, the death penalty was soon abolished throughout most of the continent. Likewise, the fall of [[communism]] in [[Central Europe|Central]] and [[Eastern Europe]] was soon followed by popular aspirations to emulate neighboring [[Western Europe]]. In these countries, public support for the death penalty had decreased. Hence, there was not much objection when the death penalty was abolished as an entry condition for membership in the [[European Union]]. The European Union and the [[Council of Europe]] both strictly require member states not to practice the death penalty. | |

| − | [[ | + | On the other hand, the rapidly [[industrialization|industrializing]] democracies of [[Asia]] did not experience a history of excessive use of the death penalty by governments against their own people. In these countries the death penalty enjoys strong public support, and the matter receives little attention from the government or the [[mass media|media]]. Moreover, in countries where democracy is not well established, such as a number of [[Africa]]n and [[Middle East]]ern countries, support for the death penalty remains high. |

| − | + | The [[United States]] never had a history of excessive capital punishment, yet capital punishment has been banned in several states for decades (the earliest is [[Michigan]]). In other states the death penalty is in active use. The death penalty in the United States remains a contentious issue. The U.S. is one of the few countries where there are contending efforts both to abolish and to retain the death penalty, fueled by active public discussion of its merits. | |

===Juvenile capital punishment=== | ===Juvenile capital punishment=== | ||

| − | The death penalty for [[Adolescence|juvenile]] offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime) has become increasingly rare. The only countries | + | The death penalty for [[Adolescence|juvenile]] offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime) has become increasingly rare. The only countries that have executed juvenile offenders since 1990 include [[People's Republic of China|China]], [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]], [[Iran]], [[Nigeria]], [[Pakistan]], [[Saudi Arabia]], the [[United States|U.S.]] and [[Yemen]].<ref>[http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGACT500152004/ “Stop Child Executions! Ending the death penalty for child offenders,”] Amnesty International (September 15, 2004). Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> |

| − | The United States Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in [[Thompson v. Oklahoma]] (1988), and for all juveniles in [[Roper v. Simmons]] (2005) | + | The United States Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in ''[[Thompson v. Oklahoma]]'' (1988), and for all juveniles in ''[[Roper v. Simmons]]'' (2005). In 2002, the [[United States Supreme Court]] outlawed the execution of individuals with [[mental retardation]].<ref>[http://archives.cnn.com/2002/LAW/06/20/scotus.executions/ “Supreme Court bars executing mentally retarded,"] CNN.com (June 25, 2002). Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | ||

| + | The [[United Nations]] [[Convention on the Rights of the Child]], which forbids capital punishment for juveniles, has been signed and ratified by all countries except for the U.S. and [[Somalia]].<ref>UNICEF, Convention of the Rights of the Child – FAQ.</ref> The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights maintains that the death penalty for juveniles has become contrary to customary [[international law]]. | ||

| − | + | ===Public opinion=== | |

| + | Both in abolitionist and retentionist [[democracy|democracies]], the government's stance often has wide public support and receives little attention by politicians or the [[mass media|media]]. In countries that have abolished the death penalty, debate is sometimes revived by a spike in serious, violent [[crime]]s, such as [[murder]]s or [[terrorism|terrorist]] attacks, prompting some countries (such as [[Sri Lanka]] and [[Jamaica]]) to end their moratoriums on its use. In retentionist countries, the debate is sometimes revived by a miscarriage of justice, though this more often leads to legislative efforts to improve the judicial process rather than to abolish the death penalty. | ||

| − | + | In the [[United States|U.S.]], [[public opinion]] surveys have long shown a majority in favor of capital punishment. An [[ABC|ABC News]] survey in July 2006 found 65 percent in favor of capital punishment, consistent with other polling since 2000.<ref>ABC News, [http://abcnews.go.com/images/Politics/1015a3DeathPenalty.pdf "Capital Punishment, 30 Years On: Support, but Ambivalence as Well,"] (PDF, July 1, 2006). Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> About half the American public says the death penalty is not imposed frequently enough and 60 percent believe it is applied fairly, according to a Gallup poll] in May 2006.<ref>[http://www.pollingreport.com/crime.htm Crime / Law Enforcement,] Polling Report.com. Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> Yet surveys also show the public is more divided when asked to choose between the death penalty and life without parole, or when dealing with juvenile offenders.<ref>[http://www.publicagenda.org/issues/major_proposals_detail.cfm?issue_type=crime&list=3 Crime: Bills and Proposals: Gallup 5/2004,] Public Agenda.org. Retrieved August 8, 2007.</ref><ref>[http://www.publicagenda.org/issues/major_proposals_detail.cfm?issue_type=crime&list=10 Crime: Bills and Proposals: ABC News 12/2003,] Public Agenda.org. Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> Roughly six in ten people told Gallup they don't believe capital punishment deters murder and majorities believe at least one innocent person has been executed in the past five years.<ref>[http://www.publicagenda.org/issues/major_proposals_detail.cfm?issue_type=crime&list=5 Crime: Bills and Proposals: Gallup Organization 5/2004,] Public Agenda.org. Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref><ref>[http://www.publicagenda.org/issues/major_proposals_detail.cfm?issue_type=crime&list=8 Crime: Bills and Proposals: Gallup Organization 5/2003,] Public Agenda.org. Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | == | + | ==The movement toward abolition of the death penalty== |

| − | + | [[File:Cesare Beccaria in Dei delitti crop.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Cesare Beccaria]] | |

| + | Modern opposition to the death penalty stems from the [[Italy|Italian]] philosopher [[Cesare Beccaria]] (1738-1794), who wrote ''Dei Delitti e Delle Pene (On Crimes and Punishments)'' (1764). Beccaria, who preceded [[Jeremy Bentham]] as an exponent of [[utilitarianism]], aimed to demonstrate not only the injustice, but even the futility from the point of view of [[social welfare]], of [[torture]] and the death penalty. Influenced by the book, [[Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor|Grand Duke Leopold II]] of [[Habsburg]], famous monarch of the [[Age of Enlightenment]] and future emperor of [[Austria]], abolished the death penalty in the then-independent [[Tuscany]], the first permanent abolition in modern times. On November 30, 1786, after having ''de facto'' blocked capital executions (the last was in 1769), Leopold promulgated the reform of the [[penal code]] that abolished the death penalty and ordered the destruction of all the instruments for capital execution in his land. In 2000 Tuscany's regional authorities instituted an annual holiday on November 30 to commemorate the event. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first democracy in recorded history to ban capital punishment was the state of [[Michigan]], which did so on March 1, 1847. Its 160-year ban on capital punishment has never been repealed. The first country to ban capital punishment in its constitution was the Roman Republic (later incorporated into [[Italy]]), in 1849. [[Venezuela]] abolished the death penalty in 1863 and [[Portugal]] did so in 1867. The last execution in Portugal had taken place in 1846. | ||

| − | + | Several international organizations have made the abolition of the death penalty a requirement of membership, most notably the [[European Union]] (EU) and the [[Council of Europe]]. The Sixth Protocol (abolition in time of peace) and the Thirteenth Protocol (abolition in all circumstances) to the [[European Convention on Human Rights]] prohibit the death penalty. All countries seeking membership to the EU must abolish the death penalty, and those seeking to join the Council of Europe must either abolish it or at least declare a moratorium on its use. For example, Turkey, in its efforts to gain EU membership, suspended executions in 1984 and ratified the Thirteenth Protocol in 2006. | |

| − | + | Most existing international treaties categorically exempt death penalty from prohibition in case of serious crime, most notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Among non-governmental organizations, [[Amnesty International]] and [[Human Rights Watch]] are noted for their opposition to capital punishment. | |

| − | + | ==Religious views== | |

| − | + | The official teachings of [[Judaism]] approve the death penalty in principle but the standard of proof required for its application is extremely stringent, and in practice it has been abolished by various [[Talmud|Talmudic]] decisions, making the situations in which a death sentence could be passed effectively impossible and hypothetical. | |

| − | + | Some [[Christianity|Christians]] interpret John 8:7, when [[Jesus of Nazareth|Jesus]] rebuked those who were about to stone an [[adultery|adulterous]] woman to death, as condemnation of the death penalty. In that incident Jesus sought instead the woman's repentance, and with that he forgave her and commanded her to start a new life. Preserving her life gave her the opportunity to reform and become a righteous woman—a far better outcome than had her life been cut short by stoning. In Matthew 26:52 Jesus also condemned the ''[[lex talionis]]'', saying that all who take the sword will perish by the sword. | |

| − | + | The most egregious use of the death penalty was to kill the [[saint]]s and [[prophet]]s whom [[God]] sent to bring enlightenment to humanity. Jesus and [[Socrates]] were two outstanding victims of judicial use of the death penalty. Hence, Christians as well as Enlightenment thinkers have sought the abolition of capital punishment. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Mennonites]] and [[Quakers]] have long opposed the death penalty. The [[Lambeth Conference]] of [[Anglicanism|Anglican]] and [[Episcopalian]] [[bishop]]s condemned the death penalty in 1988. Contemporary [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholics]] also oppose the death penalty. The recent encyclicals ''[[Humanae Vitae]]'' and ''[[Evangelium Vitae]]'' set forth a position denouncing capital punishment alongside [[abortion]] and [[euthanasia]] as violations of the right to life. While capital punishment may sometimes be necessary if it is the only way to defend society from an offender, with today's [[penal system]] such a situation requiring an execution is either rare or non-existent.<ref>[http://www.vatican.va/edocs/ENG0141/__PP.HTM ''Evangelium Vitae Ioannes Paulus PP. II'',] Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | On the other hand, the traditional Catholic position was in support of capital punishment, as per the theology of [[Thomas Aquinas]], who accepted the death penalty as a necessary deterrent and prevention method, but not as the means of vengeance. Both [[Martin Luther]] and [[John Calvin]] followed the traditional reasoning in favor of capital punishment, and the [[Augsburg Confession]] explicitly defends it. Some [[Protestantism|Protestant]] groups have cited Genesis 9:6 as the basis for permitting the death penalty. | |

| − | + | [[Islam]]ic law ([[Sharia]]) calls for the death penalty for a variety of offenses. However, the victim or the family of the victim has the right to pardon. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Hinduism|Hindu]] scriptures hold that the authorities have an obligation to punish criminals, even to the point of the death penalty, as a matter of [[Dharma]] and to protect society at large. Based on the doctrine of [[reincarnation]], if the offender is punished for his crimes in this lifetime, he is cleansed and will not have to suffer the effects of that [[karma]] in a future life. | |

| − | + | Indeed, the belief is widespread in most religions that it benefits the guilty criminal to willingly suffer execution in order to purify himself for the next world. For example, this Muslim ''hadith'': | |

| − | + | <blockquote>A man came to the Prophet and confessed four times that he had had illicit intercourse with a woman, while all the while the prophet turned his back to him. The Prophet turned around... and asked him whether he knew what fornication was, and he replied, "Yes, I have done with her unlawfully what a man may lawfully do with his wife." He asked him what he meant by this confession, and the man replied that he wanted him to purify him. So he gave the command and the man was stoned to death. Then God's Prophet heard one of his Companions saying to another, "Look at this man whose fault was concealed by God but who could not leave the matter alone, so that he was stoned like a dog." ... He replied, "By Him in whose hand is my soul, he is now plunging among the rivers of Paradise."<ref>"Hadith of Abu Dawud," in ''World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts'' (New York: Paragon House, 1991, ISBN 0892261293), p. 762.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | On the other hand, these same religions hold that a criminal who confesses with heartfelt repentance deserves the mercy of the court.<ref>"Laws of Manu 8.314-316," ''World Scripture'', 762.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | [[Buddhism]] generally disapproves of capital punishment. The sage [[Nagarjuna]] called for rulers to [[exile|banish]] murderers rather than execute them.<ref>"Precious Garland 331-337," ''World Scripture'', 761.</ref> The [[Dalai Lama]] has called for a worldwide moratorium on use of the death penalty, based on his belief that even the most incorrigible criminal is capable of reform.<ref>[http://www.deathpenaltyreligious.org/education/perspectives/dalailama.html Tenzin Gyatso, The Fourteenth Dalai Lama: Message Supporting the Moratorium on the Death Penalty] Retrieved March 18, 2007.</ref> |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | ==The capital punishment debate== | |

| + | Capital punishment has long been a subject of controversy. Opponents of the death penalty argue that life imprisonment is an effective substitute, that capital punishment may lead to irreversible miscarriages of justice, or that it violates the criminal's [[right to life]]. Supporters insist that the death penalty is justified (at least for [[murder]]ers) by the principle of [[Retributive justice|retribution]], that life imprisonment is not an equally effective deterrent, and that the death penalty affirms society's condemnation of severe [[crime]]s. Some arguments revolve around empirical data, such as whether the death penalty is a more effective deterrent than life imprisonment, while others employ abstract [[morality|moral]] judgments. | ||

| − | + | === Ethical and philosophical positions=== | |

| − | + | From the standpoint of [[philosophy|philosophical]] [[ethics]], the debate over the death penalty can be split into two main philosophical lines of argument: [[deontology|deontological]] (''[[a priori and a posteriori|a priori]]'') arguments based upon either natural rights or virtues, and [[utilitarianism|utilitarian]]/[[consequentialism|consequentialist]] arguments. | |

| − | The | + | The deontological objection to the death penalty asserts that the death penalty is "wrong" by its nature, mostly due to the fact that it amounts to the violation of the right to life, a universal principle. Most anti-death penalty organizations, such as [[Amnesty International]], base their stance on human rights arguments. |

| − | + | Deontic justification of the death penalty is based on justice—also a universal principle—arguing that the death penalty is right by nature because retribution against the violator of another's life or liberty is just. | |

| − | + | [[Virtue]] arguments against the death penalty hold that it is wrong because the process is cruel and inhumane. It brutalizes the society at large and desensitizes and dehumanizes participants of the judicial process. In particular, it extinguishes the possibility of rehabilitation and redemption of the perpetrator(s). | |

| − | + | Proponents counter that without proper retribution, the judicial system further brutalizes the victim or victim's family and friends, which amounts to secondary victimization. Moreover, the judicial process which applies the death penalty reinforces the sense of justice among participants as well as the citizens as a whole, and might even provide incentive for the convicted to own up to their crime. | |

| − | == | + | ===Wrongful convictions=== |

| − | |||

| − | + | The death penalty is often opposed on the grounds that, because every criminal justice system is fallible, innocent people will inevitably be executed by mistake,<ref>Amnesty International, [http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGAMR510691998?open&of=ENG-392/ "Fatal flaws: innocence and the death penalty in the USA"] (November 1998). Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> and the death penalty is both irreversible and more severe than lesser [[punishment]]s. Even a single case of an innocent person being executed is unacceptable. Yet [[statistics]] show that this fate is not rare: Between 1973 and 2006, 123 people in 25 U.S. states were released from death row when new evidence of their innocence emerged.<ref name="fallibility2">Death Penalty Information Center, [http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?did=412&scid=6 Innocence and the Death Penalty.] Retrieved August 9, 2007</ref> | |

| − | + | Some opponents of the death penalty believe that, while it is unacceptable as currently practiced, it would be permissible if criminal justice systems could be improved. However more staunch opponents insist that, as far as capital punishment is concerned, criminal justice is irredeemable. [[United States Supreme Court]] justice [[Harry Blackmun]], for example, famously wrote that it is futile to "tinker with the machinery of death." In addition to simple human fallibility, there are numerous more specific causes of wrongful convictions. Convictions may rely solely on witness statements, which are often unreliable. New [[forensics|forensic]] methods, such as [[DNA]] testing, have brought to light errors in many old convictions.<ref>Barbara McCuen, [http://speakout.com/activism/issue_briefs/1231b-1.html "Does DNA Technology Warrant a Death Penalty Moratorium?"] (May 2000). Retrieved August 9, 2007</ref> Suspects may receive poor legal representation. The [[American Civil Liberties Union]] has argued that "the quality of legal representation [in the U.S.] is a better predictor of whether or not someone will be sentenced to death than the facts of the crime."<ref>[http://www.aclu.org/capital/unequal/10390pub20031008.html "Inadequate Representation,"] American Civil Liberties Union (October 2003). Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | Supporters of the death penalty argue that these criticisms apply equally to life imprisonment, which can also be imposed in error, and that incarceration is also irreversible if the innocent dies in prison. | |

| − | [[ | + | ===Right to life=== |

| + | Critics of the death penalty commonly argue that it is a violation of the [[right to life]] or of the "sanctity of life." They may hold that the right to life is a [[natural right]] that exists independently of laws made by people. The right to life is inviolable; it demands that a life only be taken in exceptional circumstances, such as in [[self-defense]] or as an act of [[war]], and therefore that it violates the right to life of a criminal if she or he is executed. Defenders of the death penalty counter that these critics do not appear to have a problem with depriving offenders of their right to liberty—another natural right—as occurs during incarceration. Thus they are inconsistent in their application of natural rights. | ||

| − | [[ | + | The theory of natural rights, as put forth by the philosopher [[John Locke]], values both the right to life and the right to liberty, and specifically accepts both incarceration and execution as appropriate actions for an offender who has violated the rights of others to life and liberty; in doing so they forfeited their rights to life and liberty. As this theory is the basis for the [[United Nations]] [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]], U.N. [[treaty|treaties]] specifically permit the death penalty for serious criminal offenses. |

| − | + | ===Cruel and unusual punishment=== | |

| − | [[ | + | [[Image:GarroteExecution1901.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Garotte Execution]] |

| + | Opponents of the death penalty often argue that is inhumane, even a form of [[torture]]. While some hold that all forms of execution are inhumane, most arguments deal only with specific methods of execution. Thus the [[electric chair]] and the [[gas chamber]] have been criticized for the pain and suffering they cause the victim. All U.S. jurisdictions that currently use the gas chamber offer [[lethal injection]] as an alternative and, save [[Nebraska]], the same is true of the electric chair. | ||

| − | + | Lethal injection was introduced in the United States in an effort to make the death penalty more humane. However, there are fears that, because the cocktail of drugs used in many executions paralyzes the victim for some minutes before death ensues, victims may endure suffering not apparent to observers. The suffering caused by a method of execution is also often exacerbated in the case of "botched" executions.<ref>Amnesty International, [http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGACT500011998?open&of=ENG-TWN/ "Lethal Injection: The Medical Technology of Execution."] Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | Proponents of the death penalty point out that that incarceration is also inhumane, often producing severe psychological [[depression (psychology)|depression]]. The political writer [[Peter Hitchens]] has argued that the death penalty is more humane than life imprisonment. | |

| − | + | ===Brutalizing effect=== | |

| − | [[ | + | The brutalization hypothesis argues that the death penalty has a coarsening effect upon [[society]] and upon those officials and jurors involved in a criminal justice system which imposes it. It sends a message that it is acceptable to kill in some circumstances, and demonstrates society's disregard for the "sanctity of life." Some insist that the brutalizing effect of the death penalty may even be responsible for increasing the number of [[murder]]s in jurisdictions in which it is practiced. When the state carries out executions, it creates a seeming justification for individuals to commit murder, or as they see it, "justifiable homicide" because, like the state, they feel their action was appropriate.<ref>Jon Sorensen, Robert Wrinkle, Victoria Brewer, and James Marquart, 1999, "Capital punishment and Deterrence: Examining the Effect of Executions on Murder in Texas,", ''Crime and Delinquency'' 45(4): 481-493.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Discrimination=== | |

| + | In the [[United States]], a disproportionate number of African-Americans and Hispanics are on death row. Thus it is argued that the race of the person can affect the likelihood that they receive a death sentence. However, this disproportion may simply be the result of these minorities committing more capital crimes. In the large majority of [[murder]]s the perpetrator and the victim are of the same race. Opponents of the death penalty have not been able to prove any inherent bias in the legal system, or that there is an implicit or explicit policy to persecute minorities. On the other hand, these populations are more likely to suffer [[poverty]] and thus be unable to afford competent legal representation, which would result in more convictions and harsher sentences. The perception of racial bias is widespread; a recent study showed that just 44 percent of black Americans support the death penalty for convicted murderers, compared with 67 percent of the general population.<ref>The Gallup Organization, [http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?scid=23&did=1266 Gallup Poll: Who supports the death penalty?] (November 2004). Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Proponents point out that the debate could easily turn to more equitable application of the death penalty, which may increase the support for death penalty among minorities, who are themselves disproportionately the victims of crimes. They also argue that the problem of [[racism]] applies to the entire penal justice system, and should not be falsely attributed to the validity of death penalty itself. | |

| − | == | + | === Prevention and Deterrence=== |

| − | + | [[Utilitarianism|Utilitarian]] arguments surrounding capital punishment turn on analysis of the number of lives being saved or lost as a result of applying the death penalty. Primarily, execution prevents the perpetrator from committing further [[murder]]s in the future. Furthermore there is the deterrent effect: threat of the death penalty deters potential murders and other serious crimes such as [[drug trafficking]]. In the pre-modern period, when authorities had neither the resources nor the inclination to detain criminals indefinitely, the death penalty was often the only available means of prevention and deterrent. | |

| + | Opponents of the death penalty argue that with today's [[penal system]], prevention and deterrence are equally well served by life imprisonment. Proponents argue that life imprisonment is less effective deterrence than the death penalty. Life imprisonment also does not prevent murder within prison; however, that issue can be dealt with simply by removing the dangerous inmates to solitary confinement. | ||

| + | The question of whether or not the death penalty deters murder usually revolves around [[statistics|statistical]] studies, but such studies have shown no clear result.<ref>Death Penalty Information Center, [http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?scid=12&did=167 Facts about Deterrence and the Death Penalty.] Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> Some studies have shown a correlation between the death penalty and [[murder]] rates—in other words, where the death penalty applies, murder rates are also high.<ref>Joanna M. Shepherd, [http://judiciary.house.gov/media/pdfs/shepherd042104.pdf#search='capital%20punishment%20terrorist' Capital Punishment and the Deterrence of Crime,] (Written Testimony for the House Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security), April 2004. Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> This correlation can be interpreted to mean either that the death penalty increases murder rates by brutalizing society (see above), or that high murder rates cause the state to retain the death penalty. | ||

| − | == | + | ===Economic arguments=== |

| − | + | Economic arguments have been produced from both opponents and supporters of the death penalty.<ref>Martin Kasten, "An Economic Analysis of the Death Penalty," ''University Avenue Undergraduate Journal of Economics'' (1996).</ref><ref>Phil Porter, [http://www.mindspring.com/~phporter/econ.html "The Economics of Capital Punishment"] (1998). Retrieved August 9, 2007.</ref> Opponents of the death penalty point out that capital cases usually cost more than life imprisonment due to the extra court costs, such as appeals and extra supervision. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Proponents counter by pointing out the economic benefits of [[plea-bargaining]], particularly in the U.S., where the accused plead guilty to avoid the death penalty. This plea requires the accused to forfeit any subsequent appeals. Furthermore, the threat of the death penalty encourages accomplices to testify against other defendants and induces criminals to lead investigators to the bodies of victims. Proponents of the death penalty, therefore, argue that the death penalty significantly reduces the cost of the judicial process and criminal investigation. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | While opponents of the death penalty concede the economic argument, especially in terms of plea bargaining, they point out that plea bargaining increases the likelihood of a miscarriage of justice by penalizing the innocent who are unwilling to accept a deal, and this should be counted as a cost. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ==Conclusion== |

| − | + | Given the death penalty's history of abuse as a tool of oppression, its abolition—or at least its restriction to [[punishment]] for only the most serious [[crimes]]—is a sign of humanity's progress. The rarity with which capital punishment has been employed in many societies since the mid-twentieth century is an indication of how much people have come to value the right to life. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In some situations capital punishment has remained a necessary though unfortunate option for preserving justice and the social order. However, since everyone is destined to live on in eternity and bear forever the consequences of their actions, it is better if they have the opportunity in this life to repent and make some form of restitution for their misdeeds. Hence, prevention and deterrence is better managed through the penal system, giving offenders through their years of incarceration the opportunity to reflect on their crimes and reform themselves. Ultimately, though, the most effective and desirable deterrent lies not in the external threat of punishment but within the [[conscience]] of each individual and their desire to live in a peaceful, prosperous society. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Footnotes== | |

| − | + | <div style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> | |

| − | + | {{reflist}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | *Bedau, Hugo Adam and Paul G. Cassell (eds.). 2005. ''Debating the Death Penalty: Should America Have Capital Punishment? The Experts on Both Sides Make Their Case''. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195179804 | ||

| + | *Hanks, Gardner C. 1997. ''Against the Death Penalty: Christian and Secular Arguments Against Capital Punishment''. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. ISBN 0836190750 | ||

| + | *Hitchens, Peter. 2003. ''A Brief History of Crime''. Montgomeryville, PA: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1843541486 | ||

| + | *Schabas, William. 2005. ''The Abolition of the Death Penalty in International Law''. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052181491X | ||

| + | *Wilson, Andrew (ed.) 1991. ''World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts.'' New York: Paragon House. ISBN 0892261293 | ||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 25, 2023. | ||

| + | *[http://usliberals.about.com/od/deathpenalty/i/DeathPenalty.htm Pros & Cons of the Death Penalty and Capital Punishment] – About.com: U.S. Liberals | ||

| + | * [http://www.clarkprosecutor.org/html/links/dplinks.htm 1000+ Death Penalty Links] – Office of the Clark County Prosecuting Attorney, Jeffersonville, Indiana | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credits|Capital_punishment|79982668|Use_of_capital_punishment_worldwide|79601475|Capital_punishment_debate|79693492|List_of_methods_of_capital_punishment|79605975|}} |

Latest revision as of 21:02, 25 November 2023

Capital punishment, or the death penalty, is the execution of a convicted criminal by the state as punishment for the most serious crimes—known as capital crimes. The word "capital" is derived from the Latin capitalis, which means "concerning the head"; therefore, to be subjected to capital punishment means (figuratively) to lose one's head. The death penalty when meted out according to law is quite different from murder, which is committed by individuals for personal ends. Nevertheless, human life has supreme value. Regimes that make prolific use of capital punishment, especially for political or religious offenses, violate the most important human right—the right to life.

The death penalty was historically misused, meted out for minor crimes, and to suppress political dissent and religious minorities. Such misuse of the death penalty greatly declined in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and today it has been abolished in many countries, particularly in Europe and Latin America. In most countries where it is retained, it is reserved as a punishment for only the most serious crimes: premeditated murder, espionage, treason, and in some countries, drug trafficking. Among some countries, however, use of the death penalty is still common.

Capital punishment remains a contentious issue, even where its use is limited to punishment of only the most serious crimes. Supporters argue that it deters crime, prevents recidivism, and is an appropriate punishment for the crime of murder. Opponents argue that it does not deter criminals more than would life imprisonment, that it violates human rights, and runs the risk of executing some who are wrongfully convicted, particularly minorities and the poor. Punishment that allows criminals to reflect and reform themselves is arguably more appropriate than execution. Yet, in the ideal society, human beings should be able to recognize, based on their own conscience, that crimes deemed serious enough to merit the death penalty or life imprisonment constitute undesirable, unacceptable behavior.

History

Even before there were historical records, tribal societies enforced justice by the principle of lex talionis: "an eye for an eye, a life for a life." Thus, death was the appropriate punishment for murder. The biblical expression of this principle (Exod. 21:24) is understood by modern scholars to be a legal formula to guide judges in imposing the appropriate sentence. However, it hearkens back to tribal society, where it was understood to be the responsibility of the victim's relatives to exact vengeance upon the perpetrator or a member of his family. The person executed did not have to be an original perpetrator of the crime because the system was based on tribes, not individuals. This form of justice was common before the emergence of an arbitration system based on the state or organized religion. Such acts of retaliation established rough justice within the social collective and demonstrated to all that injury to persons or property would not go unpunished.

Revenge killings are still accepted legal practice in tribally-organized societies, for example in the Middle East and Africa, surviving alongside more advanced legal systems. However, when it is not well arbitrated by the tribal authorities, or when the murder and act of revenge cross tribal boundaries, a revenge killing for a single crime can provoke retaliation and escalate into a blood feud, or even a low-level war of vendetta (as in contemporary Iraq or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict).

Compared to revenge killings, use of formal executions by a strong governing authority was a small step forward. The death penalty was authorized in the most ancient written law codes. For example, the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1800 B.C.E.) set different punishments and compensation according to the different class/group of victims and perpetrators. The Hebrew Bible laid down the death penalty for murder, kidnapping, magic, violation of the Sabbath, blasphemy, and a wide range of sexual crimes, although evidence suggests that actual executions were rare.[1]

Nevertheless, with the expansion of state power, the death penalty came to be used more frequently as a means to enforce that power. In ancient Greece, the Athenian legal system was first written down by Draco in about 621 B.C.E.; there the death penalty was applied for a particularly wide range of crimes. The word "draconian" derives from Draco's laws. Similarly, in medieval and early modern Europe, the death penalty was also used as a generalized form of punishment. In eighteenth-century Britain, there were 222 crimes which were punishable by death, including crimes such as cutting down a tree or stealing an animal. Almost invariably, however, sentences of death for property crimes were commuted to transportation to a penal colony or to a place where the felon worked as an indentured servant.[2]

The emergence of modern democracies brought with it the concepts of natural rights and equal justice for all citizens. At the same time there were religious developments within Christianity that elevated the value of every human being as a child of God. In the nineteenth century came the movement to reform the prison system and establish "penitentiaries" where convicts could be reformed into good citizens. These developments made the death penalty seem excessive and increasingly unnecessary as a deterrent for the prevention of minor crimes such as theft. As well, in countries like Britain, law enforcement officials became alarmed when juries tended to acquit non-violent felons rather than risk a conviction that could result in execution.

The world wars in the twentieth century entailed massive loss of life, not only in combat, but also by summary executions of enemy combatants. Moreover, authoritarian states—those with fascist or communist governments—employed the death penalty as a means of political oppression. In the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, and in Communist China, millions of civilians were executed by the state apparatus. In Latin America, tens of thousands of people were rounded up and executed by the military in their counterinsurgency campaigns. Partly as a response to these excesses, civil organizations have increasingly emphasized the securing of human rights and abolition of the death penalty.

Methods of execution

Methods of execution have varied over time, and include:

- Burning, especially for religious heretics and witches, at the stake

- Burial alive (also known as "the pit")

- Crucifixion

- Crushing by elephant or a weight

- Decapitation or beheading (as by sword, axe, or guillotine)

- Drawing and quartering (Considered by many to be the cruelest of punishments)

- Electric chair

- Gas chamber

- Hanging

- Impalement

- Lethal injection

- Poisoning (as in the execution of Socrates)

- Shooting by firing squad (common for military executions)

- Shooting by a single shooter (performed on a kneeling prisoner, as in China)

- Stoning

Movements towards "humane" execution

The trend has been to move to less painful, or more "humane" methods of capital punishment. France at the end of the eighteenth century adopted the guillotine for this reason. Britain in the early nineteenth century banned drawing and quartering. Hanging by turning the victim off a ladder or by dangling him from the back of a moving cart, which causes a slow death by suffocation, was replaced by hanging where the subject is dropped a longer distance to dislocate the neck and sever the spinal cord. In the United States the electric chair and the gas chamber were introduced as more humane alternatives to hanging; and these have since been superseded by lethal injection, which subsequently was criticized as being too painful.

The death penalty worldwide

At one time capital punishment was used in almost every part of the globe; but in the latter decades of the twentieth century many countries abolished it. In China serious cases of corruption are still punished by the death penalty. In some Islamic countries, sexual crimes including adultery and sodomy carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as apostasy, the formal renunciation of Islam. In times of war or martial law, even in democracies, military justice has meted out death sentences for offenses such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.[3]

Amnesty International classifies countries in four categories. As of 2006, 68 countries still maintained the death penalty in both law and practice. Eight-eight countries had abolished it completely; 11 retained it, but only for crimes committed in exceptional circumstances (such as crimes committed in time of war). Thirty countries maintain laws permitting capital punishment for serious crimes but allowed it to fall into disuse. Among countries that maintained the death penalty, only seven executed juveniles (under 18). Despite this legal picture, countries may still practice extrajudicial execution sporadically or systematically outside their own formal legal frameworks.

China performed more than 3,400 executions in 2004, amounting to more than 90 percent of executions worldwide. Iran performed 159 executions in 2004.[4] The United States performed 60 executions in 2005. Texas has conducted more executions than any of the other states in the United States that still permit capital punishment, with 370 executions between 1976 and 2006. Singapore has the highest execution rate per capita, with 70 hangings for a population of about four million.

Where the death penalty was widely practiced as a tool of political oppression in poor, undemocratic, and authoritarian states, movements grew strongest to abolish the practice. Abolitionist sentiment was widespread in Latin America in the 1980s, when democratic governments were replacing authoritarian regimes. Guided by its long history of Enlightenment and Catholic thought, the death penalty was soon abolished throughout most of the continent. Likewise, the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe was soon followed by popular aspirations to emulate neighboring Western Europe. In these countries, public support for the death penalty had decreased. Hence, there was not much objection when the death penalty was abolished as an entry condition for membership in the European Union. The European Union and the Council of Europe both strictly require member states not to practice the death penalty.

On the other hand, the rapidly industrializing democracies of Asia did not experience a history of excessive use of the death penalty by governments against their own people. In these countries the death penalty enjoys strong public support, and the matter receives little attention from the government or the media. Moreover, in countries where democracy is not well established, such as a number of African and Middle Eastern countries, support for the death penalty remains high.

The United States never had a history of excessive capital punishment, yet capital punishment has been banned in several states for decades (the earliest is Michigan). In other states the death penalty is in active use. The death penalty in the United States remains a contentious issue. The U.S. is one of the few countries where there are contending efforts both to abolish and to retain the death penalty, fueled by active public discussion of its merits.

Juvenile capital punishment

The death penalty for juvenile offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime) has become increasingly rare. The only countries that have executed juvenile offenders since 1990 include China, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the U.S. and Yemen.[5] The United States Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), and for all juveniles in Roper v. Simmons (2005). In 2002, the United States Supreme Court outlawed the execution of individuals with mental retardation.[6]

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which forbids capital punishment for juveniles, has been signed and ratified by all countries except for the U.S. and Somalia.[7] The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights maintains that the death penalty for juveniles has become contrary to customary international law.

Public opinion

Both in abolitionist and retentionist democracies, the government's stance often has wide public support and receives little attention by politicians or the media. In countries that have abolished the death penalty, debate is sometimes revived by a spike in serious, violent crimes, such as murders or terrorist attacks, prompting some countries (such as Sri Lanka and Jamaica) to end their moratoriums on its use. In retentionist countries, the debate is sometimes revived by a miscarriage of justice, though this more often leads to legislative efforts to improve the judicial process rather than to abolish the death penalty.

In the U.S., public opinion surveys have long shown a majority in favor of capital punishment. An ABC News survey in July 2006 found 65 percent in favor of capital punishment, consistent with other polling since 2000.[8] About half the American public says the death penalty is not imposed frequently enough and 60 percent believe it is applied fairly, according to a Gallup poll] in May 2006.[9] Yet surveys also show the public is more divided when asked to choose between the death penalty and life without parole, or when dealing with juvenile offenders.[10][11] Roughly six in ten people told Gallup they don't believe capital punishment deters murder and majorities believe at least one innocent person has been executed in the past five years.[12][13]

The movement toward abolition of the death penalty

Modern opposition to the death penalty stems from the Italian philosopher Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794), who wrote Dei Delitti e Delle Pene (On Crimes and Punishments) (1764). Beccaria, who preceded Jeremy Bentham as an exponent of utilitarianism, aimed to demonstrate not only the injustice, but even the futility from the point of view of social welfare, of torture and the death penalty. Influenced by the book, Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg, famous monarch of the Age of Enlightenment and future emperor of Austria, abolished the death penalty in the then-independent Tuscany, the first permanent abolition in modern times. On November 30, 1786, after having de facto blocked capital executions (the last was in 1769), Leopold promulgated the reform of the penal code that abolished the death penalty and ordered the destruction of all the instruments for capital execution in his land. In 2000 Tuscany's regional authorities instituted an annual holiday on November 30 to commemorate the event.

The first democracy in recorded history to ban capital punishment was the state of Michigan, which did so on March 1, 1847. Its 160-year ban on capital punishment has never been repealed. The first country to ban capital punishment in its constitution was the Roman Republic (later incorporated into Italy), in 1849. Venezuela abolished the death penalty in 1863 and Portugal did so in 1867. The last execution in Portugal had taken place in 1846.

Several international organizations have made the abolition of the death penalty a requirement of membership, most notably the European Union (EU) and the Council of Europe. The Sixth Protocol (abolition in time of peace) and the Thirteenth Protocol (abolition in all circumstances) to the European Convention on Human Rights prohibit the death penalty. All countries seeking membership to the EU must abolish the death penalty, and those seeking to join the Council of Europe must either abolish it or at least declare a moratorium on its use. For example, Turkey, in its efforts to gain EU membership, suspended executions in 1984 and ratified the Thirteenth Protocol in 2006.

Most existing international treaties categorically exempt death penalty from prohibition in case of serious crime, most notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Among non-governmental organizations, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are noted for their opposition to capital punishment.

Religious views

The official teachings of Judaism approve the death penalty in principle but the standard of proof required for its application is extremely stringent, and in practice it has been abolished by various Talmudic decisions, making the situations in which a death sentence could be passed effectively impossible and hypothetical.

Some Christians interpret John 8:7, when Jesus rebuked those who were about to stone an adulterous woman to death, as condemnation of the death penalty. In that incident Jesus sought instead the woman's repentance, and with that he forgave her and commanded her to start a new life. Preserving her life gave her the opportunity to reform and become a righteous woman—a far better outcome than had her life been cut short by stoning. In Matthew 26:52 Jesus also condemned the lex talionis, saying that all who take the sword will perish by the sword.

The most egregious use of the death penalty was to kill the saints and prophets whom God sent to bring enlightenment to humanity. Jesus and Socrates were two outstanding victims of judicial use of the death penalty. Hence, Christians as well as Enlightenment thinkers have sought the abolition of capital punishment.

Mennonites and Quakers have long opposed the death penalty. The Lambeth Conference of Anglican and Episcopalian bishops condemned the death penalty in 1988. Contemporary Catholics also oppose the death penalty. The recent encyclicals Humanae Vitae and Evangelium Vitae set forth a position denouncing capital punishment alongside abortion and euthanasia as violations of the right to life. While capital punishment may sometimes be necessary if it is the only way to defend society from an offender, with today's penal system such a situation requiring an execution is either rare or non-existent.[14]

On the other hand, the traditional Catholic position was in support of capital punishment, as per the theology of Thomas Aquinas, who accepted the death penalty as a necessary deterrent and prevention method, but not as the means of vengeance. Both Martin Luther and John Calvin followed the traditional reasoning in favor of capital punishment, and the Augsburg Confession explicitly defends it. Some Protestant groups have cited Genesis 9:6 as the basis for permitting the death penalty.

Islamic law (Sharia) calls for the death penalty for a variety of offenses. However, the victim or the family of the victim has the right to pardon.

The Hindu scriptures hold that the authorities have an obligation to punish criminals, even to the point of the death penalty, as a matter of Dharma and to protect society at large. Based on the doctrine of reincarnation, if the offender is punished for his crimes in this lifetime, he is cleansed and will not have to suffer the effects of that karma in a future life.

Indeed, the belief is widespread in most religions that it benefits the guilty criminal to willingly suffer execution in order to purify himself for the next world. For example, this Muslim hadith:

A man came to the Prophet and confessed four times that he had had illicit intercourse with a woman, while all the while the prophet turned his back to him. The Prophet turned around... and asked him whether he knew what fornication was, and he replied, "Yes, I have done with her unlawfully what a man may lawfully do with his wife." He asked him what he meant by this confession, and the man replied that he wanted him to purify him. So he gave the command and the man was stoned to death. Then God's Prophet heard one of his Companions saying to another, "Look at this man whose fault was concealed by God but who could not leave the matter alone, so that he was stoned like a dog." ... He replied, "By Him in whose hand is my soul, he is now plunging among the rivers of Paradise."[15]

On the other hand, these same religions hold that a criminal who confesses with heartfelt repentance deserves the mercy of the court.[16]

Buddhism generally disapproves of capital punishment. The sage Nagarjuna called for rulers to banish murderers rather than execute them.[17] The Dalai Lama has called for a worldwide moratorium on use of the death penalty, based on his belief that even the most incorrigible criminal is capable of reform.[18]

The capital punishment debate

Capital punishment has long been a subject of controversy. Opponents of the death penalty argue that life imprisonment is an effective substitute, that capital punishment may lead to irreversible miscarriages of justice, or that it violates the criminal's right to life. Supporters insist that the death penalty is justified (at least for murderers) by the principle of retribution, that life imprisonment is not an equally effective deterrent, and that the death penalty affirms society's condemnation of severe crimes. Some arguments revolve around empirical data, such as whether the death penalty is a more effective deterrent than life imprisonment, while others employ abstract moral judgments.

Ethical and philosophical positions

From the standpoint of philosophical ethics, the debate over the death penalty can be split into two main philosophical lines of argument: deontological (a priori) arguments based upon either natural rights or virtues, and utilitarian/consequentialist arguments.

The deontological objection to the death penalty asserts that the death penalty is "wrong" by its nature, mostly due to the fact that it amounts to the violation of the right to life, a universal principle. Most anti-death penalty organizations, such as Amnesty International, base their stance on human rights arguments.

Deontic justification of the death penalty is based on justice—also a universal principle—arguing that the death penalty is right by nature because retribution against the violator of another's life or liberty is just.

Virtue arguments against the death penalty hold that it is wrong because the process is cruel and inhumane. It brutalizes the society at large and desensitizes and dehumanizes participants of the judicial process. In particular, it extinguishes the possibility of rehabilitation and redemption of the perpetrator(s).

Proponents counter that without proper retribution, the judicial system further brutalizes the victim or victim's family and friends, which amounts to secondary victimization. Moreover, the judicial process which applies the death penalty reinforces the sense of justice among participants as well as the citizens as a whole, and might even provide incentive for the convicted to own up to their crime.

Wrongful convictions

The death penalty is often opposed on the grounds that, because every criminal justice system is fallible, innocent people will inevitably be executed by mistake,[19] and the death penalty is both irreversible and more severe than lesser punishments. Even a single case of an innocent person being executed is unacceptable. Yet statistics show that this fate is not rare: Between 1973 and 2006, 123 people in 25 U.S. states were released from death row when new evidence of their innocence emerged.[20]

Some opponents of the death penalty believe that, while it is unacceptable as currently practiced, it would be permissible if criminal justice systems could be improved. However more staunch opponents insist that, as far as capital punishment is concerned, criminal justice is irredeemable. United States Supreme Court justice Harry Blackmun, for example, famously wrote that it is futile to "tinker with the machinery of death." In addition to simple human fallibility, there are numerous more specific causes of wrongful convictions. Convictions may rely solely on witness statements, which are often unreliable. New forensic methods, such as DNA testing, have brought to light errors in many old convictions.[21] Suspects may receive poor legal representation. The American Civil Liberties Union has argued that "the quality of legal representation [in the U.S.] is a better predictor of whether or not someone will be sentenced to death than the facts of the crime."[22]

Supporters of the death penalty argue that these criticisms apply equally to life imprisonment, which can also be imposed in error, and that incarceration is also irreversible if the innocent dies in prison.

Right to life

Critics of the death penalty commonly argue that it is a violation of the right to life or of the "sanctity of life." They may hold that the right to life is a natural right that exists independently of laws made by people. The right to life is inviolable; it demands that a life only be taken in exceptional circumstances, such as in self-defense or as an act of war, and therefore that it violates the right to life of a criminal if she or he is executed. Defenders of the death penalty counter that these critics do not appear to have a problem with depriving offenders of their right to liberty—another natural right—as occurs during incarceration. Thus they are inconsistent in their application of natural rights.

The theory of natural rights, as put forth by the philosopher John Locke, values both the right to life and the right to liberty, and specifically accepts both incarceration and execution as appropriate actions for an offender who has violated the rights of others to life and liberty; in doing so they forfeited their rights to life and liberty. As this theory is the basis for the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, U.N. treaties specifically permit the death penalty for serious criminal offenses.

Cruel and unusual punishment

Opponents of the death penalty often argue that is inhumane, even a form of torture. While some hold that all forms of execution are inhumane, most arguments deal only with specific methods of execution. Thus the electric chair and the gas chamber have been criticized for the pain and suffering they cause the victim. All U.S. jurisdictions that currently use the gas chamber offer lethal injection as an alternative and, save Nebraska, the same is true of the electric chair.

Lethal injection was introduced in the United States in an effort to make the death penalty more humane. However, there are fears that, because the cocktail of drugs used in many executions paralyzes the victim for some minutes before death ensues, victims may endure suffering not apparent to observers. The suffering caused by a method of execution is also often exacerbated in the case of "botched" executions.[23]

Proponents of the death penalty point out that that incarceration is also inhumane, often producing severe psychological depression. The political writer Peter Hitchens has argued that the death penalty is more humane than life imprisonment.

Brutalizing effect

The brutalization hypothesis argues that the death penalty has a coarsening effect upon society and upon those officials and jurors involved in a criminal justice system which imposes it. It sends a message that it is acceptable to kill in some circumstances, and demonstrates society's disregard for the "sanctity of life." Some insist that the brutalizing effect of the death penalty may even be responsible for increasing the number of murders in jurisdictions in which it is practiced. When the state carries out executions, it creates a seeming justification for individuals to commit murder, or as they see it, "justifiable homicide" because, like the state, they feel their action was appropriate.[24]

Discrimination

In the United States, a disproportionate number of African-Americans and Hispanics are on death row. Thus it is argued that the race of the person can affect the likelihood that they receive a death sentence. However, this disproportion may simply be the result of these minorities committing more capital crimes. In the large majority of murders the perpetrator and the victim are of the same race. Opponents of the death penalty have not been able to prove any inherent bias in the legal system, or that there is an implicit or explicit policy to persecute minorities. On the other hand, these populations are more likely to suffer poverty and thus be unable to afford competent legal representation, which would result in more convictions and harsher sentences. The perception of racial bias is widespread; a recent study showed that just 44 percent of black Americans support the death penalty for convicted murderers, compared with 67 percent of the general population.[25]

Proponents point out that the debate could easily turn to more equitable application of the death penalty, which may increase the support for death penalty among minorities, who are themselves disproportionately the victims of crimes. They also argue that the problem of racism applies to the entire penal justice system, and should not be falsely attributed to the validity of death penalty itself.

Prevention and Deterrence

Utilitarian arguments surrounding capital punishment turn on analysis of the number of lives being saved or lost as a result of applying the death penalty. Primarily, execution prevents the perpetrator from committing further murders in the future. Furthermore there is the deterrent effect: threat of the death penalty deters potential murders and other serious crimes such as drug trafficking. In the pre-modern period, when authorities had neither the resources nor the inclination to detain criminals indefinitely, the death penalty was often the only available means of prevention and deterrent.

Opponents of the death penalty argue that with today's penal system, prevention and deterrence are equally well served by life imprisonment. Proponents argue that life imprisonment is less effective deterrence than the death penalty. Life imprisonment also does not prevent murder within prison; however, that issue can be dealt with simply by removing the dangerous inmates to solitary confinement.

The question of whether or not the death penalty deters murder usually revolves around statistical studies, but such studies have shown no clear result.[26] Some studies have shown a correlation between the death penalty and murder rates—in other words, where the death penalty applies, murder rates are also high.[27] This correlation can be interpreted to mean either that the death penalty increases murder rates by brutalizing society (see above), or that high murder rates cause the state to retain the death penalty.

Economic arguments

Economic arguments have been produced from both opponents and supporters of the death penalty.[28][29] Opponents of the death penalty point out that capital cases usually cost more than life imprisonment due to the extra court costs, such as appeals and extra supervision.

Proponents counter by pointing out the economic benefits of plea-bargaining, particularly in the U.S., where the accused plead guilty to avoid the death penalty. This plea requires the accused to forfeit any subsequent appeals. Furthermore, the threat of the death penalty encourages accomplices to testify against other defendants and induces criminals to lead investigators to the bodies of victims. Proponents of the death penalty, therefore, argue that the death penalty significantly reduces the cost of the judicial process and criminal investigation.

While opponents of the death penalty concede the economic argument, especially in terms of plea bargaining, they point out that plea bargaining increases the likelihood of a miscarriage of justice by penalizing the innocent who are unwilling to accept a deal, and this should be counted as a cost.

Conclusion

Given the death penalty's history of abuse as a tool of oppression, its abolition—or at least its restriction to punishment for only the most serious crimes—is a sign of humanity's progress. The rarity with which capital punishment has been employed in many societies since the mid-twentieth century is an indication of how much people have come to value the right to life.

In some situations capital punishment has remained a necessary though unfortunate option for preserving justice and the social order. However, since everyone is destined to live on in eternity and bear forever the consequences of their actions, it is better if they have the opportunity in this life to repent and make some form of restitution for their misdeeds. Hence, prevention and deterrence is better managed through the penal system, giving offenders through their years of incarceration the opportunity to reflect on their crimes and reform themselves. Ultimately, though, the most effective and desirable deterrent lies not in the external threat of punishment but within the conscience of each individual and their desire to live in a peaceful, prosperous society.

Footnotes

- ↑ William Schabas, The Abolition of the Death Penalty in International Law (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 052181491X).

- ↑ "Death Penalty," Michigan State University and Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved August 9, 2007.