Slave trade

Slave trade has been and continues to be an economic commodity based on human life. Currently, this practise is called human trafficking and takes place in an underground market that operates outside of a recognized legal system. In other eras, slave trade was conducted openly and legally. Slavery has been a part of human civilization for thousands of years up to the present. It was practised in ancient Egypt, Pre-Greek and Greek society, the Roman Empire, in the Middle East, Europe and the Americas. In the United States, a bitter Civil War was fought over the issue of slavery and slave trade.

The qualifier for the enterprise of slave trade and human trafficking is found in the huge profits that derive from the use of power over vulnerable and/or weaker populatons of people to meet the demand of the international marketplace. "The economics of human trafficking include a huge demand for low-cost, vulnerable people in settings where the rule of law is felt faintly."(J. Miller, 2006) Such places include brothels, private homes, farms, and factories.

Human Trafficking

Trafficking in human beings is the commercial trade ("smuggling") of human beings, who are subjected to involuntary acts such as begging, sexual exploitation (eg. prostitution and forced marriage), or unfree labour (eg. involuntary servitude or working in sweatshops). Trafficking involves a process of using physical force, fraud, deception, or other forms or coercion or intimidation to obtain, recruit, harbour, and transport people.

African Slave Trade

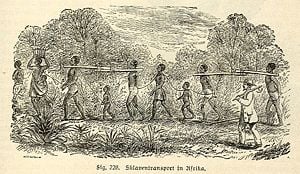

The trading of slaves has been carried on for thousands of years in Africa. The first main line of supply passed through the Sahara, to which during and after the Age of Exploration, added itself the Atlantic slave trade, through which slavery became an institution mainly considered to be one of African-derived slaves and non-African slave owners.

Despite its illegality, the African slave trade continues today in parts of the continent. The contemporary slave trade focuses principally on the theft and sale of children into slavery as child soldiers and sex workers; secondarily, on the forced sale of women into slavery, typically for use in the sex trade.

History

The earliest external slave trade was the trans-Saharan slave trade. Although there had long been some trading up the Nile River and very limited trading across the western desert, the transportation of large numbers of slaves did not become viable until camels were introduced from Arabia in the 10th century. At this point, a trans-Saharan trading network came into being to transport slaves north. There is little hard evidence of numbers, but it has been estimated that from the 10th to the 19th century some 6,000 to 7,000 slaves were transported north each year. Over time this added up to several million people moving north, however the annual numbers were small enough that it is thought by many scholars to have had relatively little demographic impact on either West Africa or the Maghreb. Frequent intermarriages meant that the slaves were quickly assimilated in North Africa. Unlike in the Americas, slaves in North Africa were mainly servants rather than labourers, and an equal or greater number of females than males were taken, who were often employed as chambermaids to women of harems. It was also not uncommon to turn male slaves into eunuchs.[1] Slaves purchased from black slave dealers in West African regions known as the Slave Coast, Gold Coast, and Côte d'Ivoire were sold into slavery as a result of a defeat in black on black tribal warfare. Mighty black kings in the Bight of Biafra near modern-day Senegal and Benin sold their captives internally and then to European slave traders for such things as metal cookware, rum, livestock, and seed grain. Also during this time, the European powers namely Portugal, Spain, France and England, were vying for majority control of the African slave trade, although having little effect on the continual internal black on black, or Arab trading. Great Britain's existing colonies in the Lesser Antilles and their effective naval control of the Mid Atlantic forced other countries to abandon their enterprises due to inefficiency in cost. The English crown provided a charter giving the Royal African Company monopoly over the African slave routes until 1712.[2]

The trade in slaves across the Indian Ocean also has a long history beginning with the control of sea routes by Arab traders in the ninth century. It is estimated that only a few thousand slaves were taken each year from the Red Sea and Indian Ocean coast. They were sold throughout the Middle East and India. This trade accelerated as superior ships led to more trade and greater demand for labour on plantations in the region. Eventually, tens of thousands per year were being taken.[3]

The Atlantic slave trade developed much later, but it would eventually be by far the largest and have the greatest impact. The first Europeans to arrive on the coast of Guinea were the Portuguese; the first European to actually buy slaves in the region was Antão Gonçalves, a Portuguese explorer. Originally interested in trading mainly for gold and spices, they set up colonies on the uninhabited islands of Sao Tome. In the 16th century the Portuguese settlers found that these volcanic islands were ideal for growing sugar. Sugar growing is a laborious undertaking and Portuguese settlers were difficult to attract due to the heat, lack of infrastructure, and hard life. To cultivate the sugar the Portuguese turned to large numbers of African slaves. Elmina Castle on the Gold Coast, originally built by the Portuguese in 1482 to control the gold trade, became an important depot for slaves that were to be transported to the New World.[4]

Increasing penetration of the Americas by the Portuguese created another huge demand for labour in Brazil, for farming, mining, and other tasks. To meet this, a trans-Atlantic slave trade soon developed. Slave-based economies quickly spread to the Caribbean and the southern portion of what is today the United States. These areas all developed an insatiable demand for slaves. From its beginning it is estimated that some 12 million slaves were taken from Africa to the Americas. The result of this trade is one of the largest migrations in history. These numbers are hotly disputed by scholars, precision is quite difficult, yet today the general consensus is that these numbers are fairly reliable. A small number of slaves were also shipped to Europe while some were also transported to other areas of Africa, mostly to South Africa.[5]

Why African slaves?

In the late 15th century, Europeans (Spanish and Portuguese first) began to explore, colonize and conquer the territory in the Americas. Using weapons such as gun power they easily defeated the indigenous people, whom they named "Indians". The European colonists attempted to enslave some of the Indians to perform hard physical labour, but found they were not good workers, with the poor conditions and diseases like smallpox which the Europeans brought in with them, indigenous numbers gradually decreased. The idea of using africans from sub-Saharan Africa as slaves initially came from the existing Arabian and Persian slave trade along East Africa which Portuguese sailors came into contact with in the 15th century. The Europeans had also noted the West African practice of enslaving prisoners of war (a common phenomenon among many peoples on all of the continents). They soon started bartering these captive slaves with their black slave owners for guns, brandy and other goods, that were only produced outside of Africa, and this gave rise to an increasing demand for black tribes to continue capturing ever more Africans for the purpose of selling them into slavery to white Europeans, but trading with Arabs and other internal black tribes still continued. The African slaves were more resistant to European diseases than the Indians and a regular trade was soon established.[1]

Expanding European empires in the New World lacked one major resource: a workforce. In most cases the Native Americans had proved unreliable (most of them were dying from diseases brought over from Europeans), and Europeans were unsuited to the climate and suffered under tropical diseases. This is where the Africans came in. They were excellent workers: they often had experience of agriculture and keeping cattle, they were used to a tropical climate, resistant to tropical diseases, and they could be "worked very hard" on plantations or in mines.[2]

Effects

While, often, no one disputes the harm done to the slaves themselves, the effects of the trade on African societies are much debated due to the apparent massive wealth black Africans were making by selling their own enslaved people to the more profitable Europeans. In the 19th century, European abolitionists slowly began to see slavery as an unmitigated evil. This view continued with scholars into the 1960s and 70s such as Basil Davidson, who conceded it might have had some benefits while still acknowledging its largely negative impact on Africa. Today, however, some scholars assert that slavery did not have a wholly disastrous effect on those left behind in Africa.[6]

These scholars assert that the numbers of slaves exported were large, but so was the population from which they were drawn. At its peak, the Atlantic slave trade took about 90,000 slaves per year out of a total population of around 25 million in just Guinea, where the vast majority originated. This number was significant, yet only a moderate annual growth rate in population was enough to sustain it by replacement. Therefore, the slave trade is unlikely to have caused a decrease in the population of West Africa, even as it may have reduced or even halted population growth in some regions.[7]

All three slave-trading routes tapped into local trading patterns. Europeans or Arabs in Africa very rarely mounted expeditions to capture slaves. It was far easier and more common to make use of existing black African middlemen and slave traders. Slavery has long been present in Africa for millennia, as some say it is still today even with children, though some historians prefer to describe African slavery as feudalism, arguing it was more like the system that controlled the peasantry of Western Europe during the Middle Ages or Russia into the 19th century than slavery as it was practiced in the Americas.[8]

The slaves came from many different sources. About half came from the societies that sold them. These might be criminals, heretics, the mentally ill, the indebted and any others that had fallen out of favour with the rulers. Most came from captured tribes in inter-tribal warfare. Little is known about the details of practices before the arrival of Europeans, and so it is difficult to tell if the number of people considered as undesirables was artificially increased to provide more slaves for export. It is believed that capital punishment and human sacrifice in the region nearly disappeared since prisoners became far too valuable to dispose of in such a way.[9]

Another source of slaves, comprising about half the total, came from military conquests of other states or tribes. It has long been contended that the slave trade greatly increased violence and warfare in the region due to the pursuit of slaves, but many argue that it is very hard to find any evidence to prove this; warfare was certainly common even before slave hunting had added such an extra inducement.[10]

Slaves were an expensive commodity, and the traders and rulers of the African states supposedly received a great deal in exchange for condemning some of their population into slavery. At the peak of the slave trade, it is said that hundreds of thousands of muskets, vast quantities of cloth, gunpowder and metals were being shipped to Guinea. Guinea's trade with Europe at the peak of the slave trade—which also included significant exports of gold and ivory—was some 3.5 million pounds Sterling per year. By contrast, the trade of the United Kingdom, the economic superpower, was about 14 million pounds per year over this same period of the late 18th century. Thus, for those left behind in Africa the standard of living increased substantially and the region became divided into highly centralized and powerful nation states, such as Dahomey and the Ashanti Confederacy. It also created a class of very wealthy and highly Europeanized traders who began to send their children to European universities.[11]

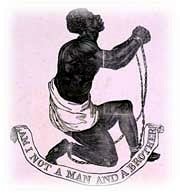

Abolition

Beginning in the late 18th century, reaction against the barbarities of the slave trade led to it being outlawed. France was Europe's first country to abolish slavery, in 1794, but it was revived by Napoleon in 1802, and only banned for good in 1848. In 1807 the British Parliament passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, under which captains of slave ships could be fined for each slave transported. This was later superseded by the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, which freed all slaves in the British Empire. Abolition was then extended to the rest of Europe. The power of the Royal Navy was subsequently used to suppress the slave trade, and while some illegal trade, mostly with Brazil, continued, the Atlantic slave trade would be eradicated by the middle of the 19th century. The Saharan and Indian Ocean trades continued, however, and even increased as new sources of slaves became available. According to Mordechai Abir, with the Russian conquest of the Caucasus, Ethiopia became the primary source to buy slaves for the Muslim world. The slave trade within Africa also increased. The British Navy could suppress much of the trade in the Indian Ocean, but the European powers could do little to affect the intra-continental trade.

The continuing anti-slavery movement in Europe became an excuse, and a trumped up reason, for the European penetration and colonisation of much of the African continent. In the late 19th century, the Scramble for Africa saw the continent rapidly divided between Imperialistic Europeans, and an early but secondary focus of all colonial regimes was the suppression of slavery and the slave trade. In response to this public pressure, Ethiopia officially abolished slavery in 1932. By the end of the colonial period they were mostly successful in this aim, and slavery is still very active in Africa even when it has gradually was moved to a wage economy. Independent nations attempting to westernise or impress Europe sometimes cultivated an image of slavery suppression, even as they, in the case of Egypt, hired European soldiers like Samuel White Baker's expedition up the Nile. Slavery has never been eradicated in Africa, and it commonly appears in states, such as Sudan, in places where law and order have collapsed.[citation needed]

Apologies

At the 2001 World Conference Against Racism in Durban South Africa, African nations demanded a clear apology for the slavery from the former slave-trading countries. Some EU nations were ready to express an apology, but the opposition, mainly from the United Kingdom, Spain, Netherlands, Portugal, and the United States blocked attempts to do so. A fear of monetary compensation was one of the reasons for the opposition.

Atlantic Slave Trade

The Atlantic slave trade was the purchase of people in and transport from West Africa and Central Africa into slavery in the New World. It is sometimes called the Maafa by African and African-American scholars, meaning holocaust or great disaster in kiSwahili. The slaves were one element of a three-part economic cycle—the Triangular Trade and its Middle Passage—which ultimately involved four continents, four centuries and the lives and fortunes of millions of people. Research published in 2006 reports the earliest known presence of African slaves in the New World. [12] A burial ground in Campeche, Mexico, suggests slaves had been brought there not long after Hernán Cortés completed the subjugation of Aztec and Mayan Mexico. Contemporary historians estimate that some 10 to 12 million individuals were taken from Africa to Europe, North, Central and South America and the Caribbean Islands. [citation needed]

Labor and slavery

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade originated as a shortage of labour in the American colonies and later the USA. The first slaves used by European colonizers were Indigenous peoples of the Americas 'Indian' peoples, but they were not numerous enough and were quickly decimated by European diseases, agricultural breakdown and harsh regime. It was also difficult to get Europeans to emigrate to the colonies, despite incentives such as indentured servitude or even distribution of free land (mainly in the English colonies that became the United States). Massive amounts of labour were needed, initially for mining, and soon even more for the plantations in the labor-intensive growing, harvesting and semi-processing of sugar (also for rum and molasses), cotton and other prized tropical crops which could not be grown profitably — in some cases, could not be grown at all — in the colder climate of Europe. It was also cheaper to import these goods from American colonies than from regions within the Ottoman Empire. To meet this demand for labour European traders thus turned to Western Africa (part of which became known as 'the Slave coast') and later Central Africa into a major source of fresh slaves.

Early trading

Starting in 1441, the first slaves were kidnapped from West Africa and brought to Portugal by Europeans as was recorded by Sir John Hawkins who claimed to have acquired captives 'by the sworde'. However, soon nearly all African slaves were sold to Europeans by other Africans involved in a slave trade that had been thriving in Africa for centuries but eagerly provided for the new, greater demand.

Eventually, European states established military bases on the West African coast in order to assist, protect and control local Africans who participated in the mass abductions. There is also evidence that, prior to the European intervention, some West African and Sahel kingdoms had participated in slave trading across the Sahara with North African states. The first slaves to be brought to the New World arrived in 1502 at the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and Dominican Republic).

African slave market

Europeans bought slaves who were captured in wars between African kingdoms and chiefdoms. African slaves were transported from these markets to the coast and sold at European trading forts in exchange for muskets and manufactured goods such as cloth or alcohol.

Europeans did not enter the interior of Africa, due to fear of disease and tribal people. Africans would capture other Africans and bring them to coastal outposts where they would be traded for goods. Enslavement also became a major by-product of war in Africa as nation states expanded through military conflicts. During such periods of rapid state formation or expansion (Asante or Dahomey being good examples), slavery formed an important element of political life long before the coming of Europeans. Conviction of a crime was another way to become a slave. Since most of these nations did not have a prison system, convict slaves were often sold.

The majority of European conquests occurred toward the end or after the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. An exception to this is the conquest of Ndongo and Kongo in Angola where warriors, citizens and even nobility were taken into slavery after the fall of the state.

African versus European slavery

Slavery in the rigid form which existed in Europe and throughout the New World was not practiced in Africa nor in the Islamic Orient. "Slavery", as it is often referred to, in African cultures was generally more like indentured servitude: "slaves" were not made to be chattel of other men, nor enslaved for life. African "slaves" were paid wages and were able to accumulate property. They often bought their own freedom and could then achieve social promotion -just as freedman in ancient Rome- some even rose to the status of kings (e.g. Jaja of Opobo). Similar arguments were used by western slave owners during the time of abolition, for example by John Wedderburn in Wedderburn v. Knight, the case that ended legal recognition of slavery in Scotland in 1776. Regardless of the legal options open to slave owners, rational cost-earning calculation and/or voluntary adoption of moral restraints often tended to mitigate (except with traders, who preferred to weed out the worthless weak individuals) the actual fate of slaves throughout history. This often resulted in a better socio-economic position and survival rate than the poorest freeborn (e.g. in poorhouses), who often also suffered cruelties including physical punishments that many slaves were spared.

African Kingdoms of the era

There were over 173 city-states and kingdoms in the African regions affected by the slave trade between 1502 and 1893, when Brazil became the last Atlantic import nation to outlaw the slave trade. Of those 173, no fewer than 68 could be deemed "nation states" with political and military infrastructures that enabled them to dominate their neighbors. Nearly every present-day nation had a pre-colonial forbear with which European traders had to barter and eventually battle. Below are 38 nation states by country with populations that correspond to African-Americans:

- Mali: Bamana Kingdom, Kenedougou, Mali Empire and Songhai Empire

- Burkina Faso: Gourma Kingdom, Gwiriko and Wagadougou

- Senegal: Jolof Empire, Toucouleur Empire, Khasso and Saalum

- Guinea-Bissau: Kaabu

- Guinea: Fuuta Jalon Kingdom

- Sierra Leone: Koya Temne and Kpaa Mende

- Cote d'Ivoire: Gyaaman and Kong Kingdom

- Ghana: Akuapem, Asante Confederacy and Manya Krobo

- Benin: Dahomey

- Nigeria: Aro Confederacy, Kingdom of Benin, Igala, Nupe and Oyo

- Cameroon Kingdoms: Bamun and Mandara kingdom

- Gabon: Orungu

- Equatorial Guinea: Otcho

- Republic of Congo: Anziku and Loango

- Democratic Republic of Congo: Kuba Kingdom, Luba Empire, Lunda Kingdom and Matamba

- Angola: Kongo Kingdom and Ndongo

There were eight principal areas used by Europeans to buy and ship slaves to the Western Hemisphere.

- Senegambia: Present day Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Guinea

- Sierra Leone: Present day Sierra Leone and Liberia

- The Windward Coast: Present day Cote d'Ivoire)

- The Gold Coast: Present-day Ghana

- The Bight of Benin or the Slave Coast: (Togo, Benin and Nigeria west of the Benue River

- The Bight of Biafra: Nigeria south of the Benue River, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea

- Central Africa (sometimes called Kongo in slave ship logs: Gabon, Democratic Republic of Congo) and Angola

- Southeast Africa (Mozambique and Madagascar).

The number of slaves sold to the new world varied throughout the slave trade. The minimum and least disputed number is 10 million. As for the distribution of slaves from regions of activity, the most widely accepted statistics [citation needed] claim Senegambia provided about 5.8%, Sierra Leone 3.4%, Windward Coast 12.1%, Gold Coast 14.4%, Bight of Benin 14.5%, Bight of Biafra 25%, Central Africa 23% and Southeast Africa 1.8%.

Ethnic groups

The different ethnic groups brought to the Americas closely corresponds to the regions of heaviest activity in the slave trade. Over 45 distinct ethnic groups were taken to the Americas during the trade. Of the 45, the ten most prominent according to slave documentation of the era are listed below.

- The Gbe Speakers of Togo and Benin (Adja, Mina, Ewe, Fon)

- The Mbundu of Angola (includes Ovimbundu)

- The BaKongo of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola

- The Igbo of Nigeria

- The Yoruba of Nigeria

- The Akan of Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire

- The Mande Speakers of Upper Guinea

- The Wolof of Senegal

- The Chamba of Nigeria

- The Makua of Mozambique

Cost in life

It is estimated that the Trans-Atlantic Slave trade involved some 30 million Africans from start to finish. Half of them died in Africa as a result of combat or waiting for months in coastal "factories". The slaves were then loaded into extremely cramped ships and given only minimal amounts of food and water. The horrific Middle Passage as it is called killed 3 million Africans as a result of torture, malnutrition, disease and even in fighting between slaves of warring ethnic groups. Treatment improved little upon reaching their destination; Africans were herded into "Seasoning Camps" located throughout the Caribbean. Jamaica had one of the most brutal of these camps operated by the British. Before being shipped off to the mainland or even local plantations on the islands, the slaves were tortured into submission in an attempt to break the will to resist. Another 2 million died in these camps. By the end of the process, two Africans died for every one that successfully arrived, culminating in a minimum of 20 million dead over 351 years.

New World destinations

African slaves were brought to Europe and the Americas to supply cheap labor. Central America only imported around 200,000. Europe topped this number at 300,000, North America, however, imported 500,000. The Caribbean was the second largest consumer of slave labor at 4 million. South America, with Brazil taking most of the slaves, imported 4.5 million before the end of the slave trade.

European competition

The trade of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic roots in the explorations of Portuguese mariners down the coast of West Africa in 1533. The first Europeans to use African slaves in the New World were the Spaniards who sought auxiliaries for their conquest expeditions and laborers on islands such as Cuba and Hispaniola (mod. Haiti-Dominican Republic) where the alarming decline in the native population had spurred the first royal laws protecting the native population, (Laws of Burgos,1512-1513). After Portugal had succeeded in establishing sugar plantations (enghenos) in northern Brazil ca. 1545, Portuguese merchants on the West African coast began to supply enslaved Africans to the sugar planters there. While at first these planters relied almost exclusively on the native Tupani for slave labor, a titantic shift toward Africans took place after 1570 following a series of epidemics which decimated the already destabilized Tupani communities. By 1630, Africans had replaced the Tupani as the largest contingent of labor on Brazilian sugar plantations, heralding equally the final collapse of the European medieval household tradition of slavery, the rise of Brazil as the largest single destination for enslaved Africans and sugar as the reason that roughly 84% of these Africans were shipped to the New World. As Britain rose in naval power and controlled more of the Americas, they became the leading slave traders, mostly operating out of Liverpool and Bristol. By the late 17th century, one out of every four ships that left Liverpool harbour was a slave trading ship [citation needed]. Other British cities also profited from the slave trade. Birmingham was the largest gun producing city in Britain at the time, and guns were traded for slaves. 75% of all sugar produced in the plantations came to London to supply the highly lucrative coffee houses there.

The slave trade was part of the triangular Atlantic trade, then probably the most important and profitable trading route in the world. Ships from Europe would carry a cargo of manufactured trade goods to Africa. They exchanged the trade goods for slaves which they would transport to the Americas, where they sold the slaves and picked up a cargo of agricultural products, often produced with slave labour, for Europe. The value of this trade route was that a ship could make a substantial profit on each leg of the voyage. The route was also designed to take full advantage of prevailing winds and currents: the trip from the West Indies or the southern U.S. to Europe would be assisted by the Gulf Stream; the outward bound trip from Europe to Africa would not be impeded by the same current.

Even though since the Renaissance some ecclesiastics actively pleaded slavery to be against the Christian teachings, as now generally held, others supported the economically opportune slave trade by church teachings and the introduction of the concept of the black man's and white man's separate roles — black men were expected to labour in exchange for the blessings of European civilization, including Christianity.

Economics of slavery

Slavery was involved in some of the most profitable industries of the time: 70% of the slaves brought to the new world were used to produce sugar, the most labour intensive crop. The rest were employed harvesting coffee, cotton, and tobacco, and in some cases in mining. The West Indian colonies of the European powers were some of their most important possessions, so they went to extremes to protect and retain them. For example, at the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, France agreed to cede the vast territory of New France to the victors in exchange for keeping the minute Antillian island of Guadeloupe (still a French overseas département).

Slave trade profits have been the object of many fantasies. Returns for the investors were not actually absurdly high (around 6% in France in the eighteenth century), but they were higher than domestic alternatives (in the same century, around 5%). Risks — maritime and commercial — were important for individual voyages. Investors mitigated it by buying small shares of many ships at the same time. In that way, they were able to diversify a large part of the risk away. Between voyages, ship shares could be freely sold and bought. All these made slave trade a very interesting investment (Daudin 2004).

By far the most successful West Indian colonies in 1800 belonged to the United Kingdom. After entering the sugar colony business late, British naval supremacy and control over key islands such as Jamaica, Trinidad, and Barbados and the territory of British Guiana gave it an important edge over all competitors; while many British did not make gains, some made enormous fortunes, even by upper class standards. This advantage was reinforced when France lost its most important colony, St. Dominigue (western Hispaniola, now Haiti), to a slave revolt in 1791 and supported revolts against its rival Britain, after the 1793 French revolution in the name of liberty (but in fact opportunistic selectivity). Before 1791, British sugar had to be protected to compete against cheaper French sugar. After 1791, the British islands produced the most sugar, and the British people quickly became the largest consumers of sugar. West Indian sugar became ubiquitous as an additive to Chinese tea. Products of American slave labour soon permeated every level of British society with tobacco, coffee, and especially sugar all becoming indispensable elements of daily life for all classes.

End of the Atlantic slave trade

In Britain and in other parts of Europe, opposition developed against the slave trade. Led by the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and establishment Evangelicals such as William Wilberforce, the movement was joined by many and began to protest against the trade, but they were opposed by the owners of the colonial holdings. Denmark, which had been very active in the slave trade, was the first country to ban the trade through legislation in 1792, which took effect in 1803. Britain banned the slave trade in 1807, imposing stiff fines for any slave found aboard a British ship. That same year the United States banned the importation of slaves. The Royal Navy, which then controlled the world's seas, moved to stop other nations from filling Britain's place in the slave trade and declared that slaving was equal to piracy and was punishable by death.

For the British to end the slave trade, significant obstacles had to be overcome. In the 18th century, the slave trade was an integral part of the Atlantic economy: the economies of the European colonies in the Caribbean, the American colonies, and Brazil required vast amounts of man power to harvest the bountiful agricultural goods. In 1790, the British West Indies islands such as Jamaica and Barbados had a slave population of 524,000 while the French had 643,000 in their West Indian possessions. Other powers such as Spain, the Netherlands, and Denmark had large numbers of slaves in their colonies as well. Despite these high populations more slaves were always required.

Harsh conditions and demographic imbalances left the slave population with well below replacement fertility levels. Between 1600 and 1800, the English imported around 1.7 million slaves to their West Indian possessions. The fact that there were well over a million fewer slaves in the British colonies than had been imported to them illustrates the conditions in which they lived.

Factors

Before the Second World War the abolition movement was primarily studied by British scholars who believed that the anti-slavery movement was probably "among the three or four perfectly virtuous pages ... in the history of nations" (Lecky, cited in Thomas 1997, p.798).

This opinion was controverted in 1944 by the West Indian historian, Eric Williams, who argued that the end of the slave trade was a result of economic transitions totally unconnected to any morality. Williams' thesis was soon brought into question as well, however. Williams based his argument upon the idea that the West Indian colonies were in decline in the early 19th century and were losing their political and economic importance to Britain. This decline turned the slave system into an economic burden that the British were willing stop.

The main difficulty with this argument is that the decline only began to manifest itself after slave trading was banned in 1807. Before then slavery was flourishing economically. The decline in the West Indies is more likely to be an effect of the suppression of the slave trade than the cause. Falling prices for the commodities produced by slave labour such as sugar and coffee can be easily discounted as evidence shows that a fall in price leads to great increases in demand and actually increases total profits for the importers. Profits for the slave trade remained at around ten percent of investment and showed no evidence of being on the decline. Land prices in the West Indies, an important tool for analyzing the economy of the area did not begin to decrease until after the slave trade was discontinued. The sugar colonies were not in decline at all; in fact they were at the peak of their economic influence in 1807.

Williams also had reason to be biased. He was heavily involved in the movements for independence of the Caribbean colonies and had a motive to try to extinguish the idea of such a munificent action by the colonial overlord. A third generation of scholars lead by the likes of Seymour Drescher and Roger Anstey have discounted most of Williams' arguments but still acknowledge that morality had to be combined with the forces of politics and economic theory to bring about the end of the slave trade.

The movements that played the greatest role in actually convincing Westminster to outlaw the slave trade were religious. Evangelical Protestant groups arose who agreed with the Quakers in viewing slavery as a blight upon humanity. These people were certainly a minority but they were fervent with many dedicated individuals. These groups also had a strong parliamentary presence, controlling 35-40 seats at their height. Their numbers were magnified by the precarious position of the government. Known as the "saints," this group was led by William Wilberforce, the most important of the anti-slave campaigners. These parliamentarians were extremely dedicated and often saw their personal battle against slavery as a divinely ordained crusade.

British influence

After the British ended their own slave trade, they felt forced by economics to induce other nations to do the same; otherwise, the British colonies would become uncompetitive with those of other nations. The British campaign against the slave trade by other nations was an unprecedented foreign policy effort. Denmark, a small player in the international slave trade, and the United States banned the trade during the same period as Great Britain. Other small trading nations that did not have a great deal to give up, such as Sweden, quickly followed suit, as did the Dutch, who were also by then a minor player.

Four nations objected strongly to surrendering their rights to trade slaves: Spain, Portugal, Brazil (after its independence), and France. Britain used every tool at its disposal to try to induce these nations to follow its lead. Portugal and Spain, which were indebted to Britain after the Napoleonic Wars, slowly agreed to accept large cash payments to first reduce and then eliminate the slave trade. By 1853, the British government had paid Portugal over three million pounds and Spain over one million pounds in order to end the slave trade. Brazil, however, did not agree to stop trading in slaves until Britain took military action against its coastal areas and threatened a permanent blockade of the nation's ports in 1852.

For France, the British first tried to impose a solution during the negotiations at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, but Russia and Austria did not agree. The French people and government had deep misgivings about conceding to Britain's demands. Britain demanded that other nations ban the slave trade and that they had the right to police the ban. The Royal Navy had to be granted permission to search any suspicious ships and seize any found to be carrying slaves, or equipped for doing so. It is especially these conditions that kept France involved in the slave trade for so long. While France formally agreed to ban the trading of slaves in 1815, they did not allow Britain to police the ban, nor did they do much to enforce it themselves. Thus a large black market in slaves continued for many years. While the French people had originally been as opposed to the slave trade as the British, it became a matter of national pride that they not allow their policies to be dictated to them by Britain. Also such a reformist movement was viewed as tainted by the conservative backlash after the French Revolution. The French slave trade thus did not end until 1848.

Arab Slave Trade

The Arab slave trade refers to the practice of slavery in the Arab world. The term "Arab" is inclusive, and traders were not exclusively Muslim, nor exclusively Arab: Persians, Berbers, Indians, Chinese and black Africans were involved in this to a greater or lesser degree. From a Western point of view, the subject merges with the Oriental slave trade, which followed two main routes in the Middle Ages:

- Overland routes across the Maghreb and Mashreq deserts (Trans-Saharan route)

- Sea routes to the east of Africa through the Red Sea and Indian Ocean (Oriental route)

The slave trade went to different destinations from the transatlantic slave trade, and supplied African slaves to the Islamic world, which at its peak stretched over three continents from the Atlantic (Morocco, Spain) to India and eastern China.

A recent and controversial topic

The history of the slave trade has given rise to numerous debates amongst historians. Firstly, specialists are undecided on the number of Africans taken from their homes; this is difficult to resolve because of a lack of reliable statistics: there was no census system in medieval Africa. Archival material for the transatlantic trade in the 16th to 18th centuries may seem more useful as a source, yet these record books were often falsified. Historians have to use imprecise narrative documents to make estimates which must be treated with caution: Luiz Felipe de Alencastro[13] states that there were 8 million slaves taken from Africa between the 8th and 19th centuries along the Oriental and the Trans-Saharan routes. Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau has put forward a figure of 17 million African people enslaved (in the same period and from the same area) on the basis of Ralph Austen's work.[14] Paul Bairoch suggests a figure of 25 million African people subjected to the Arab slave trade, as against 11 million that arrived in the Americas from the transatlantic slave trade.[15]

Another obstacle to a history of the Arab slave trade is the limitations of extant sources. There exist documents from non-African cultures, written by educated men in Arabic, but these only offer an incomplete and often condescending look at the phenomenon. For some years there has been a huge amount of effort going into historical research on Africa. Thanks to new methods and new perspectives, historians can interconnect contributions from archaeology, numismatics, anthropology, linguistics and demography to compensate for the inadequacy of the written record.

In Africa, slaves taken by African owners were often captured, either through raids or as a result of warfare, and frequently employed in manual labor by the captors. Some slaves were traded for goods or services to other African kingdoms.

The Arab slave trade from East Africa is one of the oldest slave trades, predating the European transatlantic slave trade by hundreds of years.[16]Male slaves were employed as servants, soldiers, or laborers by their owners, while female slaves, mostly from Africa, were long traded to the Middle Eastern countries and kingdoms by Arab and Oriental traders, some as female servants, others as sexual slaves. Arab, African, and Oriental traders were involved in the capture and transport of slaves northward across the Sahara desert and the Indian Ocean region into the Middle East, Persia, and the Indian subcontinent. From approximately 650 C.E. until around 1900 C.E., as many African slaves may have crossed the Sahara Desert, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean as crossed the Atlantic, and perhaps more. The Arab slave trade continued in one form or another into the early 1900s. Historical accounts and references to slave-owning nobility in Arabia, Yemen and elsewhere are frequent into the early 1920s.[17]

For some people, any mention of the slave-trading past of the Islamic world is rejected as an attempt to minimise the transatlantic trade. Yet a slave trade in the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Mediterranean pre-dates the arrival of any significant number of Europeans on the African continent. [18][19]

Historical and geographical context of the Arab slave trade

A brief review of the region and era in which the Oriental and trans-Saharan slave trade took place should be useful here. It is not a detailed study of the Islamic world, nor of Black Africa, but an outline of key points which will help with understanding the slave trade in this part of the world.

The Islamic world

The Muslim religion appeared in the 7th century CE. In the next hundred years it was quickly diffused throughout the Mediterranean area, spread by Arabs who had conquered North Africa after its long occupation by the Berbers; they extended their rule to the Iberian peninsula where they replaced the Visigoth kingdom. Arabs also took control of western Asia from Byzantium and from the Sassanid Persians. These regions therefore had a diverse range of different peoples, and their knowledge of slavery and a trade in African slaves went back to Antiquity. To some extent, these regions were unified by an Islamic culture built on both religious and civic foundations; they used the Arabic language and the dinar (currency) in commercial transactions. Mecca in Arabia, then as now, was the holy city of Islam and pilgrimage centre for all Muslims, whatever their origins. The Qur'ān, the holy book of Islam, seemed to accept slavery, a practice which pre-dated its existence, while setting limits on a master's powers over his slaves. Muslim doctors and sages often encouraged emancipation.

After the fall of the Umayyad dynasty (750), the Muslim world was divided into various political entities (caliphates, emirates, sultanates), often rivals of one another. In the 11th century, the arrival of the Turks from central Asia radically changed the geography of the Near East and of North Africa, with the establishment of the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922).

The framework of Islamic civilisation was a well-developed network of towns and oasis trading centres with the market (souk, bazaar) at its heart. These towns were inter-connected by a system of roads crossing semi-arid regions or deserts. The routes were travelled by convoys, and black slaves formed part of this caravan traffic.

Africa: 8th through 19th centuries

In the 8th century CE, Africa was dominated by Arab-Berbers in the north: Islam moved southwards along the Nile and along the desert trails.

- The Sahara was thinly populated. Nevertheless, since Antiquity there had been cities living on a trade in salt, gold, slaves, cloth, and on agriculture enabled by irrigation: Tahert, Oualata, Sijilmasa, Zaouila, and others. They were ruled by Arab or Berber chiefs (Tuaregs). Their independence was relative and depended on the power of the Maghrebi and Egyptian states.

- In the Middle Ages, sub-Saharan Africa was called Sûdân in Arabic, meaning land of the Blacks. It provided a pool of manual labour for North Africa and Saharan Africa. This region was dominated by certain states: the Ghana Empire, the Empire of Mali, the Kanem-Bornu Empire.

- In eastern Africa, the coasts of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean were controlled by native Muslims, and Arabs were important as traders along the coasts. Nubia had been a "supply zone" for slaves since Antiquity. The Ethiopian coast, particularly the port of Massawa and Dahlak Archipelago, had long been a hub for the exportation of slaves from the interior, even in Aksumite times. The port and most coastal areas were largely Muslim, and the port itself was home to a number of Arab and Indian merchants.[20]

The Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia often exported Nilotic slaves from their western borderland provinces, or from newly conquered or reconquered Muslim provinces. [21] Native muslim Ethiopian sultanates exported slaves as well, such as the sometimes independent sultanate of Adal.[22] On the coast of the Indian Ocean too, slave-trading posts were set up by Arabs and Persians. The archipelago of Zanzibar, along the coast of present-day Tanzania, is undoubtedly the most notorious example of these trading colonies. East Africa and the Indian Ocean continued as an important region for the Oriental slave trade up until the 19th century. Livingstone and Stanley were then the first Europeans to penetrate to the interior of the Congo basin and to discover the scale of slavery there. The Arab Tippo Tip extended his influence and made many people slaves. After Europeans had settled in the Gulf of Guinea, the trans-Saharan slave trade became less important. In Zanzibar, slavery was abolished late, in 1897, under Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed.

- The rest of Africa had no direct contact with Muslim slave-traders.

People playing a part in the Arab slave trade

Black slaves were captured, transported, bought and sold by some very different characters. The trade passed through a series of intermediaries and enriched some sections of the Muslim aristocracy.

Slavery fed on wars between African peoples and states, which gave rise to an internal slave trade. Those conquered owed tribute in the form of men and women reduced to capitivity. Sonni Ali Ber (1464–1492), emperor of Songhai, waged many wars to extend his territory. Even though he was a Muslim (while also retaining some belief in traditional animism), he did not hesitate to enslave other conquered Muslims. The Askia dynasty had the same policy.

In the 8th and 9th centuries, the Caliphs had tried to colonise the African shores of the Indian Ocean for commercial purposes. But these establishments were ephemeral, often founded by exiles or adventurers. The Sultan of Cairo sent slave traffickers on raids against the villages of Darfur. In the face of these attacks, the people formed militias, building towers and outer defences to protect their villages.

Aims of the slave trade and slavery

Economic motives were the most obvious. The trade resulted in large profits for those who were running it. Several cities became rich and prospered thanks to the traffic in slaves, both in the Sûdân region and in East Africa. In the Sahara desert, chiefs launched expeditions against pillagers looting the convoys. The kings of medieval Morocco had fortresses constructed in the desert regions which they ruled, so they could offer protected stopping places for caravans. The Sultan of Oman transferred his capital to Zanzibar, since he had understood the economic potential of the eastward slave trade.

There were also social and cultural reasons for the trade: in sub-Saharan Africa, possession of slaves was a sign of high social status. In Arab-Muslim areas, harems needed a "supply" of women.

Finally, it is impossible to ignore the religious and racist dimension of this trade. Punishing bad Muslims or pagans was held to be an ideological justification for enslavement: the Muslim rulers of North Africa, the Sahara and the Sahel sent raiding parties to persecute infidels: in the Middle Ages, Islamisation was only superficial in rural parts of Africa.

Racist opinions recurred in the works of Arab historians and geographers: so in the 14th century CE Ibn Khaldun could write "...the Negro nations are, as a rule, submissive to slavery, because (Negroes) have little that is (essentially) human and possess attributes that are quite similar to those of dumb animals... "[23] In the same period, the Egyptian scholar Al-Abshibi wrote, "When he (a black man) is hungry, he steals, and when he is sated, he fornicates".[24]

Geography of the slave trade

"Supply" zones

Merchants of slaves for the Orient stocked up in Europe. Danish merchants had bases in the Volga region and dealt in Slavs with Arab merchants. Circassian slaves were conspicuously present in the harems and there were many odalisques from that region in the paintings of Orientalists. Non-Islamic slaves were valued in the harems, for all roles (gate-keeper, servant, odalisque, houri, musician, dancer, court dwarf). In 9th century Baghdad, the Caliph Al-Amin owned about 7000 black eunuchs (who were completely emasculated) and 4000 white eunuchs (who were castrated).[25] In the Ottoman Empire, the last black eunuch, the slave sold in Ethiopia named Hayrettin Effendi, was freed in 1918. The slaves of Slavic origin in Al-Andalus came from the Varangians who had captured them. They were put in the Caliph's guard and gradually took up important posts in the army (they became saqaliba), and even went to take back taifas after the civil war had led to an implosion of the Western Caliphate. Columns of slaves feeding the great harems of Cordoba, Seville and Grenada were organised by Jewish merchants (mercaderes) from Germanic countries and parts of Northern Europe not controlled by the Carolingian Empire. These columns crossed the Rhône valley to reach the lands to the south of the Pyrenees.

- At sea, Barbary pirates joined in this traffic when they could capture people by boarding ships or by incursions into coastal areas.

- Nubia, Ethiopia and Abyssinia were also "exporting" regions: in the 15th century, there were Abyssinian slaves in India where they worked on ships or as soldiers. They eventually rebelled and took power (dynasty of the Habshi Kings in Bengal 1487-1493).

- The Sûdân region and Saharan Africa formed another "export" area, but it is impossible to estimate the scale, since there is a lack of sources with figures.

- Finally, the slave traffic affected eastern Africa, but the distance and local hostility slowed down this section of the Oriental trade.

Routes

Caravan trails, set up in the 9th century, went past the oases of the Sahara; travel was difficult and uncomfortable for reasons of climate and distance. Since Roman times, long convoys had transported slaves as well as all sorts of products to be used for barter. To protect against attacks from desert nomads, slaves were used as an escort. Any who slowed down the progress of the caravan were killed.

Historians know less about the sea routes. From the evidence of illustrated documents, and travellers' tales, it seems that people travelled on dhows or jalbas, Arab ships which were used as transport in the Red Sea. Crossing the Indian Ocean required better organisation and more resources than overland transport. Ships coming from Zanzibar made stops on Socotra or at Aden before heading to the Persian Gulf or to India. Slaves were sold as far away as India, or even China: there was a colony of Arab merchants in Canton. Chinese slave traders bought black slaves (Hei-hsiao-ssu) from Arab intermediaries or "stocked up" directly in coastal areas of present-day Somalia. Serge Bilé cites a 12th century text which tells us that most well-to-do families in Canton had black slaves whom they regarded as savages and demons because of their physical appearance.[26] The 15th century Chinese emperors sent maritime expeditions, led by Zheng He, to eastern Africa. Their aim was to increase their commercial influence.

Barter

Slaves were often bartered for objects of various different kinds: in the Sûdân, they were exchanged for cloth, trinkets and so on. In the Maghreb, they were swapped for horses. In the desert cities, lengths of cloth, pottery, Venetian glass beads, dyestuffs and jewels were used as payment. The trade in black slaves was part of a diverse commercial network. Alongside gold coins, cowrie shells from the Indian Ocean or the Atlantic (Canaries,Luanda) were used as money throughout black Africa (merchandise was paid for with sacks of cowries).

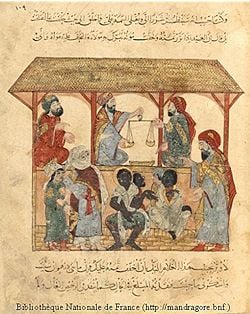

Slave markets and fairs

Black slaves were sold in the towns of the Muslim world. In 1416, al-Makrisi told how pilgrims coming from Takrur (near the Senegal river) had brought 1700 slaves with them to Mecca. In North Africa, the main slave markets were in Morocco, Algiers, Tripoli and Cairo. Sales were held in public places or in souks. Potential buyers made a careful examination of the "merchandise": they checked the state of health of a person who was often standing naked with wrists bound together. In Cairo, transactions involving eunuchs and concubines happened in private houses. Prices varied according to the slave's quality. White women were considered more valuable than other women.

Towns and ports implicated in the slave trade

|

|

Overview

Human trafficking differs from people smuggling. In the latter, people voluntarily request smuggler's service for fees and there is no deception involved in the (illegal) agreement. On arrival at their destination, the smuggled person is either free, or is required to work under a job arranged by the smuggler until the debt is repaid. On the other hand, the trafficking victim is enslaved, or the terms of their debt bondage are fraudulent or highly exploitative. The trafficker takes away the basic human rights of the victim. Victims are sometimes tricked and lured by false promises or physically forced. Some traffickers use coercive and manipulative tactics including deception , intimidation, feigned love, isolation, threat and use of physical force, debt bondage, other abuse, or even force-feeding with drugs to control their victims. [3]

Trafficked persons usually come from the poorer regions of the world, where opportunities are limited and are often from the most vulnerable in society, such as runaways, refugees, or other displaced persons, (especially in post-conflict situations, such as Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina), though they may also come from any social background, class or race. People who are seeking entry to other countries may be picked up by traffickers, and — typically — misled into thinking that they will be free after being smuggled across the border. In some cases, they are captured through slave raiding, although this is increasingly rare. Other cases may involve parents who may sell children to traffickers in order to pay off debts or gain income.

Women, who form the majority of trafficking victims, are particularly at risk from potential kidnappers who exploit lack of opportunities, promise good jobs or opportunities for study, and then force the victims to be prostitutes. Through agents and brokers who arrange the travel and job placements, women are escorted to their destinations and delivered to the employers. Upon reaching their destinations, some women learn that they have been deceived about the nature of the work they will do; most have been lied to about the financial arrangements and conditions of their employment; and all find themselves in coercive and abusive situations from which escape is both difficult and dangerous.

The main motives of a woman (and in some cases an underage girl) to accept an offer from a trafficker is for better financial opportunities for themselves or their family. In many cases traffickers initially offer ‘legitimate’ work. The main types of work offered are in the catering and hotel industry, in bars and clubs, au pair work or to study. Offers of marriage are sometimes used by traffickers as well as threats, intimidation and kidnapping. In the majority of cases, prostitution is where the women end up. Also some (migrating) prostitutes become victims of human trafficking. Some women know they will be working as prostitutes, but they have a too rosy picture of the circumstances and the conditions of the work in the country of destination.[4]

Men are also at risk of being trafficked for unskilled work predominantly involving hard labour. Other forms of trafficking include bonded and sweatshop labour, forced marriage, and domestic servitude. Children are also trafficked for both labour exploitation and sexual exploitation. On a related issue, children are forced to be child soldiers.

Many women are forced into the sex trade after answering false advertisements and others are simply kidnapped. Thousands of children are sold into the global sex trade every year. Oftentimes they are kidnapped or orphaned, and sometimes they are actually sold by their own families. These children often come from Asia, Africa, and South America.

Traffickers mostly target developing nations where the women are desperate for jobs. The women are often so poor that they can not afford things like food and health care. When the women are offered a position as a nanny or waitress, they often jump to the opportunity.

Extent

US State Department data “estimated 600,000 to 800,000 men, women, and children (are) trafficked across international borders each year, approximately 80 percent are women and girls and up to 50 percent are minors. The data also illustrate that the majority of transnational victims are trafficked into commercial sexual exploitation.” [5]. Due to the illegal nature of trafficking and differences in methodology, the exact extent is unknown.

An estimated 14,000 people are trafficked into the United States each year, although again because trafficking is illegal, accurate statistics are difficult. [6] According to the Massachusetts based Trafficking Victims Outreach and Services Networkin Massachusetts alone, there were 55 documented cases of human trafficking in 2005 and the first half of 2006 in Massachusetts. [7] In 2004, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) estimated that 600-800 persons are trafficked into Canada annually and that additional 1,500-2,200 persons are trafficked through Canada into the United States. [8]

In the United Kingdom, 71 women were known to have been trafficked into prostitution in 1998 and the Home Office recognised that the scale is likely greater as the problem is hidden and research estimates that the actual figure could be up to 1,420 women trafficked into the UK during the same peroid. [9] Trafficking in people is increasing in Africa, South Asia and into North America.

Russia is a major source of women trafficked globally for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Russia is also a significant destination and transit country for persons trafficked for sexual and labor exploitation from regional and neighboring countries into Russia, and on to the Gulf states, Europe, Asia, and North America. The ILO estimates that 20 percent of the five million illegal immigrants in Russia are victims of forced labor, which is a form of trafficking. There were reports of trafficking of children and of child sex tourism in Russia. The Government of Russia has made some effort to combat trafficking but has also been criticised for not complying with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking.[10] [11]

The majority of child trafficking cases are in Asia, although it is a global problem. In Thailand, non-governmental organisations (NGO) have estimated that up to a third of prostitutes are children under 18, many trafficked from outside Thailand. [12] In Ukraine, a survey conducted by the NGO “La Strada-Ukraine” in 2001-2003, based on a sample of 106 women being trafficked out of Ukraine found that 3% were under 18, and the US State Department reported in 2004 that incidents of minors being trafficked was increasing.

Trafficking in people has been facilitated by porous borders and advanced communication technologies, it has become increasingly transnational in scope and highly lucrative. Unlike drugs or arms, people can be "sold" several times. The opening up of Asian markets, porous borders, the end of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the former Yugoslavia have contributed to this globalization.

Some causes of trafficking include:

- Profitability

- Growing deprivation and marginalisation of the poor

- Discrimination in employment against women

- Anti-child labor laws eliminating employment for people under the age of 18

- Anti-marriage laws for people under the age of 18, resulting in single motherhood and a desperate need for income

- Restrictive immigration laws that motivate people to take greater risks

- Insufficient penalties against traffickers

International law

In 2000 the United Nations adopted the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, also called the Palermo Convention and two protocols thereto:

- Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children; and

- Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air.

All of these instruments contain elements of the current international law on trafficking in human beings.

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings [13] [14] was adopted by the Council of Europe on 16 May 2005. The aim of the convention is to prevent and combat the trafficking in human beings. Of the 46 members of the Council of Europe, so far 30 have signed the convention and 1 has ratified it. In addition, 1 non-member state has signed the convention (29 June 2006). [15]

United States law

The United States has taken a firm stance against human trafficking both within its borders and beyond. Domestically, human trafficking is prosecuted through the Civil Rights Division, Criminal Section of the United States Department of Justice. Older statutes used to protect 13th Amendment Rights within United States Borders are Title 18 U.S.C., Sections 1581 and 1584. Section 1584 makes it a crime to force a person to work against his will. This compulsion can be effected by use of force, threat of force, threat of legal coercion or by "a climate of fear", that is, an environment wherein individuals believe they may be harmed by leaving or refusing to work. Section 1581 similarly makes it illegal to force a person to work through "debt servitude".

New laws were passed under the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000. The new laws responded to a changing face of trafficking in the United States. It allowed for greater statutory maximum sentences for traffickers, provided resources for protection of and assistance for victims of trafficking and created avenues for interagency cooperation in the field of human trafficking. This law also attempted to encourage efforts to prevent human trafficking internationally, by creating annual country reports on trafficking, as well as by tying financial non-humanitarian assistance to foreign countries to real efforts in addressing human trafficking.

International NPOs, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have called on the United States to improve its measures aimed at reducing trafficking. They recommend that the United States more fully implement the "United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children" and the "United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime" and for immigration officers to improve their awareness of trafficking and support the victims of trafficking. [16][17]

Notes

- ↑ Fage pg. 256

- ↑ http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/africa_caribbean/britain_trade.htm

- ↑ Fage pg. 258

- ↑ Fage pg. 232

- ↑ Fage pg. 255

- ↑ Fage pg. 261

- ↑ Fage pg. 260

- ↑ Fage pg. 268

- ↑ Fage pg. 267

- ↑ Fage pg. 267

- ↑ Fage pg. 274

- ↑ "Skeletons Discovered: First African Slaves in New World". January 31, 2006. LiveScience.com. Accessed September 27, 2006.

- ↑ Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, Traite, in Encyclopædia Universalis (2002), corpus 22, page 902.

- ↑ Ralph Austen, African Economic History (1987)

- ↑ Paul Bairoch, Mythes et paradoxes de l'histoire économique, (1994). See also: Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes (1993)

- ↑ Mintz, S. Digital History Slavery, Facts & Myths

- ↑ Mintz, S. Digital History Slavery, Facts & Myths

- ↑ Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, in Les Collections de l'Histoire (April 2001) says:"la traite vers l'Océan indien et la Méditerranée est bien antérieure à l'irruption des Européens sur le continent"

- ↑ Mintz, S. Digital History Slavery, Facts & Myths

- ↑ Pankhurst, Richard. The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Asmara, Eritrea: The Red Sea, Inc., 1997, pp.416

- ↑ Pankhurst. Ethiopian Borderlands, pp.432

- ↑ Pankhurst. Ethiopian Borderlands, pp.59

- ↑ Ibn Khaldun The Muqaddimah trans. F.Rosenthal ed. N.J.Dawood (Princeton 1967); see also Jacques Heers, Les négriers en terre d'islam, page 177.

- ↑ François Renault, Serge Daget, Les traites négrières en Afrique, Karthala, p.56

- ↑ Bernard Lewis, Race and Color in Islam (1979)

- ↑ Serge Bilé, La légende du sexe surdimmensionné des Noirs, éditions du Rocher, 2005, p.80: "la plupart des familles aisées de Canton possédaient des esclaves noirs [...] qu'elles tenaient néanmoins pour des sauvages et des démons à cause de leur aspect physique"

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anstey, Roger: The Atlantic Slave Trade and British abolition, 1760-1810. London: Macmillan, 1975.

- Clarke, Dr. John Henrik: Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust. Slavery and the Rise of European Capitalism

- Daudin, Guillaume: "Profitability of slave and long distance trading in context : the case of eightheenth century France", Journal of Economic History, 2004.

- Diop, Er. Cheikh Anta: Precolonial Black Africa: A Comparative Study of the Political and Social Systems of Europe and Black Africa

- Drescher, Seymour: From Slavery to Freedom: Comparative Studies in the Rise and Fall of Atlantic Slavery. London: Macmillan Press, 1999.

- Emmer, P.C.: De Nederlandse slavenhandel 1500-1850 [The Dutch Slave Trade 1500-1850]. Amsterdam and Antwerpen: Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers, 2000.

- Fage, J.D. A History of Africa (Routledge, 4th edition, 2001 ISBN 0-415-25247-4)

- Lovejoy, Paul E. Transformations in Slavery 1983

- Franklin, John Hope: From Slavery to Freedom

- Rodney, Walter: How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Howard University Press; Revised edition, 1981.

- Thomas, Hugh: The Slave Trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade 1440 - 1870. London: Picador, 1997.

- Williams, Chancellor: Destruction of Black Civilization

- Williams, Eric: Capitalism & Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Bibliography

Books in English

- Edward A. Alpers, The East African Slave Trade (Berkeley 1967)

- Robert C. Davis, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

- Allan G. B. Fisher, Slavery and Muslim Society in Africa, ed. C. Hurst (London 1970, 2nd edition 2001)

- Murray Gordon, Slavery in the Arab world (New York 1989)

- Bernard Lewis, Race and slavery in the Middle East (OUP 1990)

- Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah trans. F.Rosenthal ed. N.J.Dawood (Princeton 1967)]

- Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa (Cambridge 2000)

- Ronald Segal, Islam's Black Slaves (Atlantic Books, London 2002)

Books and articles in French

- Serge Daget, De la traite à l'esclavage, du Ve au XVIIIe siècle, actes du Colloque international sur la traite des noirs (Nantes, Société française d'histoire d'Outre-Mer, 1985)

- Jacques Heers, Les Négriers en terre d'islam (Perrin, Pour l'histoire collection, Paris, 2003) (ISBN 2-262-01850-2)

- Murray Gordon, L'esclavage dans le monde arabe, du VIIe au XXe siècle (Robert Laffont, Paris, 1987)

- Bernard Lewis, Race et esclavage au Proche-Orient, (Gallimard, Bibliothèque des histoires collection, Paris, 1993) (ISBN 2-07-072740-8)

- Olivier Petré-Grenouilleau, Les Traites oubliée des négrières (la Documentation française, Paris, 2003)

- Jean-Claude Deveau, Esclaves noirs en Méditerranée in Cahiers de la Méditerranée, vol. 65, Sophia-Antipolis

- Olivier Petré-Grenouilleau, La traite oubliée des négriers musulmans in L'Histoire, special number 280 S (October 2003), pages 48-55.

External links

- Africans in America/Part 1/The Middle Passage

- Breaking the Silence: Learning about the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- The Maafa (African Holocaust)

- The Middle Passage

- A Chronology of Slavery, Abolition, and Emancipation

- Understanding Slavery Initiative; The New Site for Teachers on the British part of the transatlantic slave trade

- Set All Free - Act to end slavery - British site commemorating 200 years since the passing of Abolition of the Slave Trade Act

- Wilberforce Central site - American site commemorating 200 years since the passing of Abolition of the Slave Trade Act

- African Holocaust African history of legacy of slavery

- Set All Free - Act to end slavery - British site commemorating 200 years since the passing of Abolition of the Slave Trade Act

- Wilberforce Central site - American site commemorating 200 years since the passing of Abolition of the Slave Trade Act

- The John Newton Project

- [18] Mintz, S., Digital History/Slavery Facts & Myths

Amnesty International

- Amnesty International UK trafficking/forced prostitution

- Amnesty International USA - Human Trafficking

- Amnesty International - Council of Europe: Protect victims of people trafficking

- Amnesty International - concern over trafficking and the World Cup in Germany

- Amnesty International - Kosovo: Trafficked women and girls have human rights

- Amnesty International - Facts and figures on trafficking of women and girls for forced prostitution in Kosovo

- Amnesty International - Serbia and Montenegro: Shameful investigation into sex-trafficking case

Other organisations and campaigns

- The Anti Trafficking Alliance - Tackling Sexual Trafficking, Supporting its Survivors.

- Angel Coalition - Russia/CIS

- "Animus Association" - Bulgaria

- Ansar Burney Trust - Human and Civil Rights Organisation based in Pakistan

- 'Anti Slavery - Trafficking

- Asia Regional Cooperation to Prevent People Trafficking

- Coalition to Abolish Slavery & Trafficking (CAST)

- The Coalition Against Trafficking in Women

- Terre des hommes

- 'The Emancipation Network: Fighting trafficking with economic empowerment'

- ‘End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes’ international NGO

- Face to Face Bulgaria (in Bulgarian) in English

- Fair Fund human rights and development group - trafficking

- Freedom Network (USA): To Empower Trafficked and Enslaved Persons

- Fundación Esperanza - Colombia

- Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women

- Human Trafficking Search Net

- 'Human Rights Watch - Trafficking

- International Organization for Adolescents (IOFA)

- Justice for Children International (JFCI)

- La Strada International Association

- La Strada Ukraine: Preventing trafficking of women in Central and Eastern Europe

- LEFOE - Austria

- 'Maiti Nepal "Crusading for the prevention of girl trafficking, rescue, rehabilitation and reintegration of survivors of trafficking."

- 'MTV anti-trafficking campaign

- The National MultiCultural Institute

- New York City Community Response to Trafficking (NYCRT)

- New York State Anti-Trafficking Coalition

- Operation Day's Work 2005 Norwegian NGO

- The POPPY Project, Eaves – UK based support for trafficking victims

- Coalition against the slavery of women and children in Angeles, Philippines

- Project Constance: Public Service Web Portal on Human Trafficking, Organized Crimes & Violence Against Women

- Transnational AIDS Prevention among Migrant Prostitutes in Europe Project- TAMPEP

- 'Stop Trafficking - Danish NGO'

- "South Texas Coalition Against Human Trafficking/Slavery" - South Texas, USA

- Stop Human Trafficking

- Task Force on Human Trafficking - Israel based NGO

- "Texas Association Against Sexual Assault - Human Trafficking" - Texas, USA

- TIPinAsia Anti Trafficking in Person in Asia Web Portal

- Trafficking Victims Outreach & Services Network - Massachusetts, USA

- 'VietACT: Vietnamese Alliance to Combat Trafficking

- Vital Voices— Global Partnership US based NGO

- Women's Consortuim of Nigeria- WOCON

- World Hope International

- Child Marriage Film www.childmarriage.org - (A film by Neeraj Kumar)

Articles

- 'Slavery in the 21st century - BBC

- 'Asia's sex trade is 'slavery' - BBC

- Asia's child sex victims ignored – BBC

- 'Sex trade's reliance on forced labour - BBC

- 'A modern slave's brutal odyssey - BBC

- Baltic girls forced into sex slavery - BBC

- 'Slaves auctioned' by traffickers - BBC

- 'Child traffic victims 'failed'- BBC

- On the trail of a trafficked child - BBC

- Suspected baby traders arrested - BBC

- Jail for Chinese baby traffickers - BBC

- S Africa's child sex trafficking nightmare - BBC

- 'Tracking Africa's child trafficking - BBC

- Europe warned over trafficking of children - BBC

- 'Balkans urged to curb trafficking - BBC

- Sex Slaves, Revisited - Slate.com

- 'Bosnia: Sex Slave Recounts Her Ordeal - Institute for War & Peace Reporting

- 'Moldova: Young Women From Rural Areas Vulnerable To Human Trafficking

- 'Merchants of Misery: Human Trafficking in Moldova

- People trafficking: upholding rights & understanding vulnerabilities - special issue of Forced Migration Review

- Human trafficking - University of Massachusetts resource

- 'Coalition Against Trafficking in Women Factbook

- International Organization for Migration Data and Research on Human Trafficking 2005

- HumanTrafficking.com is a program of the Polaris Project. The website is a sizeable web-based resource of news articles, journal articles, books and country-specific resources

- HumanTrafficking.org is a government sponsored resource regarding legislation, NGO partners and regional information.

- Prostitution Research

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Human Trafficking

- On The Record Series- GIRLS FOR SALE: THE SCANDAL OF TRAFFICKING FROM NIGERIA

- Blogs from the Frontlines of Trafficking- Nigeria 1

- Blogs from the Frontlines of Trafficking- Nigeria 2

- Blogs from the Frontlines of Trafficking- Italy

- 'International Labour Organization forced labour report (1MB pdf)

- 'Sex Trafficking of Women in the United States: International and Domestic Trends - Coalition Against Trafficking in Women

- Fears of rising child sex trade – The Guardian

- ‘They said I wasn’t human but something that can be bought’ – The Times

- ‘Mine for £1,300: Ileana, the teenage sex slave ready to work in London’ – The Sunday Telegraph

- 'Streets of despair - The Observer

- 'The Protection Project - Johns Hopkins University

- 'Pakistani girls forced into prostitution in ME' - The News

- 'Pakistanis released from Tanzanian slave labour arrive home' - Online

- Sex Slavery and Human Trafficking

- 'Minister accused of human trafficking' - Khaleej Times

- "Trafficked from Pakistan, raped and jailed in Saudi Arabia" - AFP

- 'Woman rescued after resisting prostitution push' - Gulf News

- Kidnapped children sold into slavery as camel racers - The Observer

- Kidnapped children starve as camel jockey slaves - The Sunday Times

- Child camel jockeys find hope - BBC

- Women and Children First: The Economics of Sex Trafficking. Lydersen, Kari. LiP Magazine, April 2002

- Traffic in Children - The Economist

- Robots of Arabia - Wired News Article

- Research based on case studies of victims of trafficking in human beings in 3 EU Member States

- The Miami Declaration of Principles on Human Trafficking (via St. Thomas University School of Law)

- Happy hookers of Eastern Europe

- Human Trafficking, Fourth report of the Dutch National Rapporteur

- Current WTO negotiations threaten to worsen the already precarious lot of migrant workers around the globe

Government and international governmental organisations

- Council of Europe - Slaves at the heart of Europe

- European Union: European Commission - Documentation Centre

- European Union: Eurojust and Human Trafficking