Difference between revisions of "New Testament" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (43 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | + | {{Books of the New Testament}} | |

| + | The '''New Testament''' is the name given to the second and final portion of the [[Christianity|Christian]] [[Bible]]. It is the sacred scripture and central element of the Christian faith. | ||

| − | + | Its original texts were written in Koine [[Greek]] by various authors after c. 45 C.E. and before c. 140. Its 27 books were gradually collected into a single volume over a period of several centuries. They consist of [[Gospel]]s recounting the life of [[Jesus]], an account of the works of the [[apostle]]s called the [[Book of Acts]], letters from [[Saint Paul]] and other early Christian leaders to various churches and individuals, and the remarkable apocalyptic work known as the [[Book of Revelation]]. | |

| + | The term New Testament came into use in the second century during a controversy among Christians over whether or not the [[Hebrew Bible]] should be included with the Christian writings as sacred scripture. Some other works which were widely read by early churches were excluded from the New Testament and relegated to the collections known as the [[Apostolic Fathers]] (generally considered orthodox) and the [[New Testament Apocrypha]] (including both orthodox and heretical works). Most Christians consider the New Testament to be an ''infallible'' source of doctrine, while others go even farther to affirm that it is also ''inerrant,'' or completely correct in historical and factual details as well as theologically. In recent times, however, the authority of the New Testament books has been challenged. The school of [[historical criticism]] has exposed various apparent contradictions within the texts, as well as questions of authorship and dating. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Some Christians, believing that the [[Holy Spirit]]'s revelation to the church is progressive, have questioned some of the New Testament's moral teachings—for example on [[homosexuality]], church [[hierarchy]], [[slavery]], and the role of [[women]]—as outdated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Today, the New Testament remains a central pillar of the Christian faith, and has played a major role in shaping modern Western culture. | ||

| + | [[Image:Bibel-1.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Most editions of the Christian Bible contain both the Old Testament and the New Testament.]] | ||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

The term ''New Testament'' is a translation from the Latin ''Novum Testamentum'' first coined by the second century Christian writer [[Tertullian]]. It is related to the concept expressed by the prophet [[Jeremiah]] (31:33), that translates into English as ''new covenant'': | The term ''New Testament'' is a translation from the Latin ''Novum Testamentum'' first coined by the second century Christian writer [[Tertullian]]. It is related to the concept expressed by the prophet [[Jeremiah]] (31:33), that translates into English as ''new covenant'': | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>'The time is coming," declares the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah… '</blockquote> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | : | + | [[Image:Tertullian.JPG|thumb|right|200px|Tertullian was the first writer to use the term "New Testament."]] |

| − | : | + | This concept of the new covenant is also discussed in the eighth chapter of the [[Letter to the Hebrews]], in which the "old covenant" is portrayed as inferior and even defective (Hebrews 8:7). Indeed, many Christians considered the "old" covenant with the Jews to be obsolete. |

| + | |||

| + | Use of the term ''New Testament'' to describe a collection of first and second-century Christian Greek Scriptures can be traced back to [[Tertullian]] (in ''Against [[Praxeas]]'' 15).<ref>Clifton J. Allen, ''The Broadman Bible Commentary: Volume 8'' (Broadman Press, 1969).</ref> In ''Against [[Marcion]]'', written ''circa'' 208 C.E., he writes of | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | the Divine Word, who is doubly edged with the two testaments of the [[Torah|law]] and the [[gospel]].<ref>Tertullian, [http://earlychristianwritings.com/text/tertullian123.html "Chapter XIV"] ''Against Marcion, Book III''. Retrieved September 24, 2018.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Tertullian's day, some even considered the God of the [[Hebrew Bible]] to be a very different being than the [[Heavenly Father]] of [[Jesus]]. Tertullian took the orthodox position, that the God of the [[Jews]] and the God of the Christians are one and the same. He therefore wrote: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | it is certain that the whole aim at which he [Marcion] has strenuously laboured, even in the drawing up of his [[Antitheses]], centres in this, that he may establish a diversity between the Old and the New Testaments, so that his own [[Christ]] may be separate from the [[Creator God|Creator]], as belonging to this rival god, and as alien from the law and the [[Neviim|prophets]].<ref>Tertullian, [http://earlychristianwritings.com/text/tertullian124.html "Chapter VI"] ''Against Marcion, Book IV''. Retrieved September 24, 2018.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | By the fourth century, the existence—even if not the exact contents—of both an Old and New Testament had been established. [[Lactantius]], a third–fourth century Christian author wrote in his early-fourth-century Latin ''Institutiones Divinae'' (''Divine Institutes''): | |

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| − | + | But all scripture is divided into two Testaments. That which preceded the advent and passion of Christ—that is, the [[Torah|law]] and the [[Neviim|prophets]]—is called the Old; but those things which were written after His resurrection are named the New Testament. The Jews make use of the Old, we of the New: but yet they are not discordant, for the New is the fulfilling of the Old, and in both there is the same testator ...<ref>Lactantius, [http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf07.iii.ii.iv.xx.html "Chapter XX"] ''The Divine Institutes, Book IV''. Retrieved September 24, 2018.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | </blockquote> | + | |

| + | While Christians have thus come to refer to the Hebrew Scriptures as the [[Old Testament]], Jews prefer the term [[Hebrew Bible]], or [[Tanakh]], the latter word being an acronym for its three basic component parts: the [[Torah]] (Book of Moses), [[Nevi'im]] ([[Prophet]]s), and ''[[Ketuvim]]'' (Writings). | ||

==Books== | ==Books== | ||

| − | The majority of Christian denominations have settled on the same | + | The majority of Christian denominations have settled on the same 27-book [[Biblical canon|canon]]. It consists of the four narratives of [[Jesus|Jesus Christ's]] ministry, called "[[Gospel]]s"; a narrative of the [[Twelve Apostles|apostles]]' ministries in the [[Early Christianity|early church]] called the ''[[Book of Acts]]''; 21 early letters, commonly called "[[epistle]]s," written by various authors and consisting mostly of Christian counsel and instruction; and a book of [[Apocalypse|apocalyptic]] [[prophecy]] known as the Book of Revelation. |

===Gospels=== | ===Gospels=== | ||

| − | Each of the | + | [[Image:KellsFol027v4Evang.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The symbols of the four Evangelists are here depicted in the [[Book of Kells]]. Clockwise from top left: [[Matthew the Evangelist|Matthew]], [[Mark the Evangelist|Mark]], [[John the Evangelist|John]], and [[Luke the Evangelist|Luke]].]] |

| − | *The [[Gospel of Matthew]], traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[Matthew the Evangelist|Matthew, son of Alphaeus]] | + | Each of the [[Gospel]]s narrates the ministry of [[Jesus of Nazareth]]. None of the Gospels originally had an author's name associated with it, but each has been an assigned an author according to tradition. Modern scholarship differs on precisely by whom, when, or in what original form the various gospels were written. |

| − | *The [[Gospel of Mark]], traditionally ascribed to [[Mark the Evangelist]], who wrote down the recollections of the Apostle [[Saint Peter|Simon Peter]] | + | *The [[Gospel of Matthew]], traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[Matthew the Evangelist|Matthew, son of Alphaeus]] |

| − | *The [[Gospel of Luke]], traditionally ascribed to [[Luke the Evangelist|Luke]], a physician and companion of [[Paul of Tarsus]] | + | *The [[Gospel of Mark]], traditionally ascribed to [[Mark the Evangelist]], who wrote down the recollections of the Apostle [[Saint Peter|Simon Peter]] |

| − | *The [[Gospel of John]], traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[John the Apostle|John, son of Zebedee]] | + | *The [[Gospel of Luke]], traditionally ascribed to [[Luke the Evangelist|Luke]], a physician and companion of [[Paul of Tarsus]] |

| + | *The [[Gospel of John]], traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[John the Apostle|John, son of Zebedee]] | ||

| − | The first three are commonly classified as the [[ | + | The first three are commonly classified as the [[synoptic Gospels]]. They contain very similar accounts of events in Jesus' life, although differing in some respects. The Gospel of John stands apart for its unique records of several miracles and sayings of Jesus not found elsewhere. Its timeline of Jesus' ministry also differs significantly from the other Gospels, and its theological outlook is also unique. |

===Acts=== | ===Acts=== | ||

| − | The [[Book of Acts]], also occasionally termed Acts of the Apostles or Acts of the Holy Spirit, is a narrative of the | + | The [[Book of Acts]], also occasionally termed ''Acts of the Apostles'' or ''Acts of the Holy Spirit'', is a narrative of the apostles' ministry after Christ's death. It is also a sequel to the third Gospel (of Luke), written by the same author. The book traces the events of the early Christian church—with the apostles Peter and Paul as the main characters—from shortly after Jesus' resurrection, through the church's spread from Jerusalem into the Gentile world, until shortly before the trial and execution of [[Saint Paul]] in [[Rome]]. |

| − | The book traces the events of the early Christian | ||

===Pauline epistles=== | ===Pauline epistles=== | ||

| − | The [[Pauline epistles]] constitute those letters traditionally attributed to [[Paul of Tarsus|Paul]], though his authorship of some of them is disputed. One letter, Hebrews, is nearly universally agreed to be by someone other than Paul. The so-called Pastoral | + | The [[Pauline epistles]] constitute those letters traditionally attributed to [[Paul of Tarsus|Paul]], though his authorship of some of them is disputed. One such letter, ''Hebrews,'' is nearly universally agreed to be by someone other than Paul. The so-called Pastoral Epistles—1 and 2 Timothy and Titus—are thought by many modern scholars to have been written by a later author in Paul's name. |

| − | + | [[File:Paul in prison by Rembrandt.jpg|thumb|225px|The Apostle Paul]] | |

*[[Epistle to the Romans]] | *[[Epistle to the Romans]] | ||

*[[First Epistle to the Corinthians]] | *[[First Epistle to the Corinthians]] | ||

| Line 53: | Line 69: | ||

===General epistles=== | ===General epistles=== | ||

| − | The General or "Catholic" Epistles are those written to the church at large by various writers. (''Catholic'' in this sense simply means ''universal'' | + | The General or "Catholic" Epistles are those written to the church at large by various writers. (''Catholic'' in this sense simply means ''universal.'') |

| − | *[[Epistle of James]], traditionally by [[James the Just|James, the brother of Jesus]] and leader of the Jerusalem church | + | *[[Epistle of James]], traditionally by [[James the Just|James, the brother of Jesus]] and leader of the Jerusalem church |

| − | *[[First Epistle of Peter]], traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[Saint Peter|Saint Peter]] | + | *[[First Epistle of Peter]], traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[Saint Peter|Saint Peter]] |

| − | *[[Second Epistle of Peter]], also traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[Saint Peter|Peter]] | + | *[[Second Epistle of Peter]], also traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[Saint Peter|Peter]] |

| − | *[[First Epistle of John]], traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[John the Apostle|John, son of Zebedee]] | + | *[[First Epistle of John]], traditionally ascribed to the Apostle [[John the Apostle|John, son of Zebedee]] |

| − | *[[Second Epistle of John]], also ascribed to the same [[John the Apostle|John]] | + | *[[Second Epistle of John]], also ascribed to the same [[John the Apostle|John]] |

| − | *[[Third Epistle of John]], similarly ascribed John | + | *[[Third Epistle of John]], similarly ascribed to John |

| − | *[[Epistle of Jude]], traditionally ascribed to [[Jude, brother of Jesus|Jude Thomas, brother of Jesus and James]] | + | *[[Epistle of Jude]], traditionally ascribed to [[Jude, brother of Jesus|Jude Thomas, brother of Jesus and James]] |

The date and authorship of each of these letters are widely debated. | The date and authorship of each of these letters are widely debated. | ||

===The Book of Revelation=== | ===The Book of Revelation=== | ||

| − | The final book of the New Testament is the [[Book of Revelation]], traditionally by the Apostle [[John the Apostle|John, son of Zebedee]] also known as [[John of Patmos]]). The book is also called the ''Apocalypse of John'' | + | The final book of the New Testament is the [[Book of Revelation]], traditionally by the Apostle [[John the Apostle|John, son of Zebedee]] (also known as [[John of Patmos]]). The book is also called the ''Apocalypse of John.'' It consists primarily of a channeled message from Jesus to seven Christian churches, together with John's dramatic vision of the [[Last Days]], the [[Second Coming]] of Christ, and the [[Final Judgment]]. |

===Apocrypha=== | ===Apocrypha=== | ||

| − | In ancient times there were dozens of Christian writings which were considered authoritative by some but not all ancient churches. These were not ultimately included in the 27-book New Testament canon. These works are considered "apocryphal," and are therefore referred to as the [[New Testament Apocrypha]]. | + | In ancient times there were dozens or even hundreds of Christian writings which were considered authoritative by some, but not all, ancient churches. These were not ultimately included in the 27-book New Testament canon. These works are considered "apocryphal," and are therefore referred to as the [[New Testament Apocrypha]]. Some were deemed by the orthodox churches to be heretical, while others were considered spiritually edifying but not early enough to be included, of dubious authorship, or controversial theologically even if not heretical. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Authorship== | ==Authorship== | ||

| − | The New Testament is a collection of works, and as such was written by multiple authors. | + | The New Testament is a collection of works, and as such was written by multiple authors. The traditional view is that all the books were written by [[Twelve apostles|apostles]] (e.g. Matthew, Paul, Peter, John) or disciples of apostles (such as Luke, Mark, etc). These traditional ascriptions have been rejected by some church authorities as early as the second century, however. In modern times, with the rise of rigorous historical inquiry and [[textual criticism]], the apostolic origin of many of the New Testament books has been called into serious question. |

| − | + | ===Paul=== | |

| − | Seven of the epistles of Paul are now generally accepted by most modern scholars as authentic. These undisputed letters include [[Romans]], [[First Corinthians]], [[Second Corinthians]], [[Galatians]], [[Philippians]], [[First Thessalonians]], and [[Philemon]]. Opinion about the [[Epistle to the Colossians]] is divided. Most critical scholars doubt that Paul wrote | + | Seven of the epistles of Paul are now generally accepted by most modern scholars as authentic. These undisputed letters include [[Romans]], [[First Corinthians]], [[Second Corinthians]], [[Galatians]], [[Philippians]], [[First Thessalonians]], and [[Philemon]]. Opinion about the [[Epistle to the Colossians]] and [[Second Thessalonians]] is divided. Most critical scholars doubt that Paul wrote the other letters attributed to him. Modern conservative Christian scholars tend to be more willing to accept the traditional ascriptions. However, few serious scholars, Christian or otherwise, still hold that Paul wrote the [[Letter to the Hebrews]]. |

| − | The authorship of all non-Pauline books | + | The authorship of all non-Pauline New Testament books has been disputed in recent times. Ascriptions are largely polarized between conservative Christian and liberal Christian as well as non-Christian experts, making any sort of scholarly consensus all but impossible. |

===The Gospel writers=== | ===The Gospel writers=== | ||

| − | The Synoptic Gospels, [[Matthew]], [[Mark]] and [[Luke]], unlike the other New Testament works, have a unique documentary relationship. The traditional | + | [[image:Two_source_hypothesis.png|225px|thumb|According to the two-source hypothesis, the sources for Matthew and Luke are the [[Gospel of Mark]] and the [[Q document]]]] |

| + | |||

| + | The Synoptic Gospels, [[Matthew]], [[Mark]] and [[Luke]], unlike the other New Testament works, have a unique documentary relationship. The traditional view—also supported by a minority of critical scholars—supposes that Matthew was written first, and Mark and Luke drew from it. A smaller group of scholars espouse Lukan priority. The dominant view among critical scholars—the [[Two-Source Hypothesis]]—is that the [[Gospel of Mark]] was written first, and both Matthew and Luke drew significantly upon Mark and another common source, known as the [[Q document|"Q Source"]], from ''Quelle,'' the German word for "source." | ||

| − | The Gospel of John is thought by | + | The Gospel of John is thought by traditional Christians to have been written by John, the son of Zebedee. He is also referred to as "the [[Beloved Disciple]]," and is particularly important in the [[Eastern Orthodox]] tradition. Critical scholarship often takes the view that John's Gospel is the product of a community including formerly [[Jewish Christians]] in the late first or early second century, who had been expelled from the Jewish community because of their insistence on the divinity of Jesus and other theological views, which caused them to take an adversarial attitude toward "the Jews." |

===Other writers=== | ===Other writers=== | ||

| − | Views about the authors of the | + | Views about the authors of the other New Testament works—such as the letters purportedly from such figures such as Peter, James, John, and Jude—fall along similar lines. Traditionalists tend to accept the designations as they have been received, while critical scholars often challenge these notions, seeing the works as mistakenly attributed to apostles, or in some case as being "pious forgeries," written in an apostle's name but not actually authored by him. |

==Date of composition== | ==Date of composition== | ||

| − | According to tradition, the earliest of the books were the letters of Paul, and the last books to be written are those attributed to John, who is traditionally said to have lived to a very old age | + | According to tradition, the earliest of the books were the letters of Paul, and the last books to be written are those attributed to John, who is traditionally said to have been the youngest of the apostles and to have lived to a very old age. [[Irenaeus of Lyons]], c. 185, stated that the Gospels of Matthew and Mark were written while Peter and Paul were preaching in Rome, which would be in the 60s, and Luke was written some time later. [[Evangelicalism|Evangelical]] and [[Traditionalism|traditionalist]] scholars generally support this dating. |

| − | Most critical scholars agree that Paul's letters were the earliest to be written. For the Gospels, they tend to date Mark no earlier than 65 and no later than 75. Matthew is dated between 70 and 85. Luke is usually placed within 80 to 95. John's Gospel is the subject of more debate, being | + | Most critical scholars agree that Paul's letters were the earliest to be written, while doubting that some of the "late" Pauline letters such as Ephesians and Timothy were actually written by Paul. For the Gospels, they tend to date Mark no earlier than 65 and no later than 75. Matthew is dated between 70 and 85. Luke is usually placed within 80 to 95. John's Gospel is the subject of more debate, being dated as early as 85 and as late as the early second century. |

A number of variant theories to the above have also been proposed. | A number of variant theories to the above have also been proposed. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Authority== | ==Authority== | ||

| − | All Christian groups respect the New Testament, but they differ in their understanding of the nature, extent, and relevance of its authority. Views of the authoritativeness of the New Testament often depend on the concept of | + | All Christian groups respect the New Testament, but they differ in their understanding of the nature, extent, and relevance of its authority. Views of the authoritativeness of the New Testament often depend on the concept of [[inspiration]], which relates to the role of God in the formation of both the New Testament and the Old [[Testament]]. Generally, the greater the direct role of God in one's doctrine of inspiration—and the less one allows for human perspectives interfering with God's [[revelation]]—the more one accepts the doctrine of Biblical [[inerrancy]] and/or the authoritativeness of the Bible. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *''[[Infallibility]]'' relates to the absolute correctness of the Bible in matters of doctrine. | |

| + | *''[[Inerrancy]]'' relates to the absolute correctness of the Bible in factual assertions (including historical and scientific assertions). | ||

| + | *''Authoritativeness'' relates to the correctness of the Bible in questions of practice in morality. | ||

| − | + | The meaning of all of these concepts depend on the supposition that the text of Bible has been properly interpreted, with consideration for the intention of the text, whether literal history, allegory or poetry, etc. | |

| − | == | + | ==Canonization== |

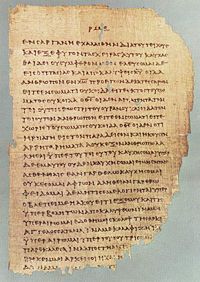

| − | + | [[Image:P46.jpg|thumb|200px|Papyrus 46, one of the earliest New Testament texts, is a fragment of Paul's First Letter to the Corinthians.]] | |

| − | + | Related to the question of authority is the issue of which books were included in the New Testament: ''[[canonization]].'' Here, as with the writing of the texts themselves, the question is related to how directly one believes God or the [[Holy Spirit]] was involved in the canonization process. Contrary to popular misconception, the New Testament canon was not decided primarily by large Church council meetings, but rather developed slowly over several centuries. Formal councils and declarations were also involved, however. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the first three centuries of the Christian church, no New Testament canon was universally recognized. Documents such as some of Paul's letters and various Gospels or [[apocalypse]]s were read publicly in certain churches, while other documents, including some later judged to be forgeries or heretical, were read in others. One of the earliest attempts at solidifying a canon was made by [[Marcion]], c. 140 C.E., who accepted only a modified version of Luke and ten of Paul's letters, while rejecting the [[Old Testament]] entirely. German scholar [[Adolf Harnack]] in ''Origin of the New Testament'' (1914)<ref>Adolf Harnack, [http://www.ccel.org/ccel/harnack/origin_nt.v.vi.html "Appendix VI"] ''Origin of the New Testament''. Retrieved September 24, 2018.</ref> argued that the orthodox Church at this time was largely an Old Testament Church without a New Testament canon and that it was against the challenge of Marcionism that the New Testament canon developed. The [[Muratorian fragment]], usually in the late second century, provides the earliest known New Testament canon attributed to mainstream (that is, not Marcionite) Christianity. It is similar, but not identical, to the modern New Testament canon. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The oldest clear endorsement of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John as being the only legitimate Gospels was written c. 180 C.E. by Bishop [[Irenaeus]] of Lyon in his polemic ''Against the Heresies.'' [[Justin Martyr]], Irenaeus, and [[Tertullian]] (all second century) held the letters of Paul to be on a par with the Hebrew Scriptures as being divinely inspired. Other books were held in high esteem but were gradually relegated to the status of [[New Testament Apocrypha]]. Several works were that were given special honor, but did not rise to the status of Scripture. These became known as the works of the [[Apostolic Fathers]], including such documents as the [[Didache]] (the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles), the epistles of [[Ignatius of Antioch]], the [[Shepherd of Hermas]], the [[Martyrdom of Polycarp]], and the [[Epistle of Barnabas]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Sainta15.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The first New Testament book list identical to the current one was published by Bishop [[Athanasius of Alexandria]] in 367 C.E.]] | |

| − | + | The [[Book of Revelation]] was the most controversial of those books that were finally accepted. Several canon lists by various Church Fathers rejected it. Also, the early church historian [[Eusebius of Caesaria]] relates that the church at Rome rejected the letter to the Hebrews on the grounds that it did not believe it to have been written by Paul (''Ecclesiastical History'' 3.3.5). | |

| − | + | The "final" New Testament canon was first listed by [[Athanasius of Alexandria]]—the leading orthodox figure in the [[Arianism|Arian]] controversy—in 367, in a letter written to his churches in Egypt.<ref> Athanasius, [http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf204.xxv.iii.iii.xxv.html "Festal Letter XXXIX"] ''Select Works and Letters''. Retrieved September 24, 2018.</ref> Also cited is the [[Council of Rome]] of 382 under the authority of [[Pope Damasus I]], but recent scholarship dates the list supposedly associated with this to a century later. Athanasius' list gained increasing recognition until it was accepted at the [[Synods of Carthage|Third Council of Carthage]] in 397. Even this council did not settle the matter, however. Certain books continued to be questioned, especially [[Epistle of James|James]] and [[Book of Revelation|Revelation]]. As late as the sixteenth century, [[Martin Luther]] questioned (but in the end did not reject) the Epistle of James, the [[Epistle of Jude]], the [[Epistle to the Hebrews]] and the [[Book of Revelation]]. | |

| − | + | Due to such challenges by Protestants, the [[Council of Trent]] reaffirmed the ''traditional canon'' as a [[dogma]] of the [[Catholic Church]]. The vote on the issue was not unanimous, however: 24 yea, 15 nay, 16 abstain.<ref>Bruce A. Metzger, ''The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance'' (Oxford University Press, 1997), 246.</ref> Similar affirmations were made by the [[Thirty-Nine Articles]] of 1563 for the [[Church of England]], the [[Westminster Confession of Faith]] of 1647 for [[Calvinism]], and the [[Synod of Jerusalem]] of 1672 for [[Greek Orthodoxy]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Language== | |

| − | + | The common languages spoken by both Jews and Gentiles in the holy land at the time of Jesus were [[Aramaic of Jesus|Aramaic]], [[Koine Greek]], and to a limited extent [[Hebrew]]. The original texts of the New Testament books written mostly or entirely in Koine Greek, the vernacular dialect in first century [[Roman province]]s of the [[Mediterranean|Eastern Mediterranean]]. They were later translated into other languages, most notably [[Latin]], [[Syriac language|Syriac]], and [[Coptic language|Coptic]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the [[Middle Ages]], translation of the New Testament was strongly discouraged by church authorities. The most notable [[Middle English]] translation, [[John Wyclif|Wyclif]]'s Bible (1383) was banned by the Oxford Synod in 1408. A Hungarian [[Hussite]] Bible appeared in the mid-fifteenth century; and in 1478, a Catalan (Spanish) translation appeared in the dialect of [[Valencia]]. In 1521, [[Martin Luther]] translated the New Testament from Greek into German, and this version was published in September 1522. [[William Tyndale]]'s English Bible (1526) met with heavy sanctions, and Tyndale himself was jailed in 1535. The Authorized [[King James Version]] is an English translation of the Christian Bible by the [[Church of England]] begun in 1604 and first published in 1611. The [[Counter-Reformation]] and missionary activity by the Jesuit order led to a large number of sixteenth century Catholic translations into various languages of the [[New World]]. | |

| − | + | Today there are hundreds if not thousands of translations of the New Testament, covering nearly every language currently spoken. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | * Abingdon Press. ''The New Interpreter's Bible: General Articles & Introduction, Commentary, & Reflections for Each Book of the Bible, Including the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books.'' Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0687278145 |

| − | * | + | * Allen, Clifton J. ''The Broadman Bible Commentary: Volume 8''. Broadman Press, 1969. |

| − | * | + | * Brown, Raymond Edward. ''An Introduction to the New Testament.'' The Anchor Bible reference library. New York: Doubleday, 1997. ISBN 0385247672 |

| + | * Ehrman, Bart D. ''Lost Christianities: The Battle for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew.'' Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0195182491 | ||

| + | * Johnson, Luke Timothy. ''Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation.'' Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 1986. ISBN 978-0800618865 | ||

| + | * Mack, Burton L. ''Who Wrote the New Testament?: The Making of the Christian Myth.'' HarperOne, 1996. ISBN 978-0060655181 | ||

| + | * Metzger, Bruce M. ''The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance.'' Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0198269540 | ||

| + | * Pelikan, Jaroslav.'' Whose Bible Is It?: A History of the Scriptures Through the Ages.'' Viking, 2005. ISBN 978-0670033850 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 11, 2022. | ||

| + | *[http://www.biblegateway.com Various versions and translations]. ''www.biblegateway.com'' | ||

| + | *[http://www.ntgateway.com/ Duke University's New Testament Gateway]. ''www.ntgateway.com'' | ||

| + | *[http://www.religioustolerance.org/inerrant.htm Overview of Inerrancy]. ''religioustolerance.org'' | ||

| + | *[http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/ Early Christian Writings]. ''www.earlychristianwritings.com'' | ||

| − | + | {{Books of the Bible}} | |

| − | + | [[Category:Bible]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

{{Credit|157216817}} | {{Credit|157216817}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:33, 11 November 2022

| New Testament |

|---|

The New Testament is the name given to the second and final portion of the Christian Bible. It is the sacred scripture and central element of the Christian faith.

Its original texts were written in Koine Greek by various authors after c. 45 C.E. and before c. 140. Its 27 books were gradually collected into a single volume over a period of several centuries. They consist of Gospels recounting the life of Jesus, an account of the works of the apostles called the Book of Acts, letters from Saint Paul and other early Christian leaders to various churches and individuals, and the remarkable apocalyptic work known as the Book of Revelation.

The term New Testament came into use in the second century during a controversy among Christians over whether or not the Hebrew Bible should be included with the Christian writings as sacred scripture. Some other works which were widely read by early churches were excluded from the New Testament and relegated to the collections known as the Apostolic Fathers (generally considered orthodox) and the New Testament Apocrypha (including both orthodox and heretical works). Most Christians consider the New Testament to be an infallible source of doctrine, while others go even farther to affirm that it is also inerrant, or completely correct in historical and factual details as well as theologically. In recent times, however, the authority of the New Testament books has been challenged. The school of historical criticism has exposed various apparent contradictions within the texts, as well as questions of authorship and dating.

Some Christians, believing that the Holy Spirit's revelation to the church is progressive, have questioned some of the New Testament's moral teachings—for example on homosexuality, church hierarchy, slavery, and the role of women—as outdated.

Today, the New Testament remains a central pillar of the Christian faith, and has played a major role in shaping modern Western culture.

Etymology

The term New Testament is a translation from the Latin Novum Testamentum first coined by the second century Christian writer Tertullian. It is related to the concept expressed by the prophet Jeremiah (31:33), that translates into English as new covenant:

'The time is coming," declares the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah… '

This concept of the new covenant is also discussed in the eighth chapter of the Letter to the Hebrews, in which the "old covenant" is portrayed as inferior and even defective (Hebrews 8:7). Indeed, many Christians considered the "old" covenant with the Jews to be obsolete.

Use of the term New Testament to describe a collection of first and second-century Christian Greek Scriptures can be traced back to Tertullian (in Against Praxeas 15).[1] In Against Marcion, written circa 208 C.E., he writes of

the Divine Word, who is doubly edged with the two testaments of the law and the gospel.[2]

In Tertullian's day, some even considered the God of the Hebrew Bible to be a very different being than the Heavenly Father of Jesus. Tertullian took the orthodox position, that the God of the Jews and the God of the Christians are one and the same. He therefore wrote:

it is certain that the whole aim at which he [Marcion] has strenuously laboured, even in the drawing up of his Antitheses, centres in this, that he may establish a diversity between the Old and the New Testaments, so that his own Christ may be separate from the Creator, as belonging to this rival god, and as alien from the law and the prophets.[3]

By the fourth century, the existence—even if not the exact contents—of both an Old and New Testament had been established. Lactantius, a third–fourth century Christian author wrote in his early-fourth-century Latin Institutiones Divinae (Divine Institutes):

But all scripture is divided into two Testaments. That which preceded the advent and passion of Christ—that is, the law and the prophets—is called the Old; but those things which were written after His resurrection are named the New Testament. The Jews make use of the Old, we of the New: but yet they are not discordant, for the New is the fulfilling of the Old, and in both there is the same testator ...[4]

While Christians have thus come to refer to the Hebrew Scriptures as the Old Testament, Jews prefer the term Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, the latter word being an acronym for its three basic component parts: the Torah (Book of Moses), Nevi'im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings).

Books

The majority of Christian denominations have settled on the same 27-book canon. It consists of the four narratives of Jesus Christ's ministry, called "Gospels"; a narrative of the apostles' ministries in the early church called the Book of Acts; 21 early letters, commonly called "epistles," written by various authors and consisting mostly of Christian counsel and instruction; and a book of apocalyptic prophecy known as the Book of Revelation.

Gospels

Each of the Gospels narrates the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth. None of the Gospels originally had an author's name associated with it, but each has been an assigned an author according to tradition. Modern scholarship differs on precisely by whom, when, or in what original form the various gospels were written.

- The Gospel of Matthew, traditionally ascribed to the Apostle Matthew, son of Alphaeus

- The Gospel of Mark, traditionally ascribed to Mark the Evangelist, who wrote down the recollections of the Apostle Simon Peter

- The Gospel of Luke, traditionally ascribed to Luke, a physician and companion of Paul of Tarsus

- The Gospel of John, traditionally ascribed to the Apostle John, son of Zebedee

The first three are commonly classified as the synoptic Gospels. They contain very similar accounts of events in Jesus' life, although differing in some respects. The Gospel of John stands apart for its unique records of several miracles and sayings of Jesus not found elsewhere. Its timeline of Jesus' ministry also differs significantly from the other Gospels, and its theological outlook is also unique.

Acts

The Book of Acts, also occasionally termed Acts of the Apostles or Acts of the Holy Spirit, is a narrative of the apostles' ministry after Christ's death. It is also a sequel to the third Gospel (of Luke), written by the same author. The book traces the events of the early Christian church—with the apostles Peter and Paul as the main characters—from shortly after Jesus' resurrection, through the church's spread from Jerusalem into the Gentile world, until shortly before the trial and execution of Saint Paul in Rome.

Pauline epistles

The Pauline epistles constitute those letters traditionally attributed to Paul, though his authorship of some of them is disputed. One such letter, Hebrews, is nearly universally agreed to be by someone other than Paul. The so-called Pastoral Epistles—1 and 2 Timothy and Titus—are thought by many modern scholars to have been written by a later author in Paul's name.

- Epistle to the Romans

- First Epistle to the Corinthians

- Second Epistle to the Corinthians

- Epistle to the Galatians

- Epistle to the Ephesians

- Epistle to the Philippians

- Epistle to the Colossians

- First Epistle to the Thessalonians

- Second Epistle to the Thessalonians

- First Epistle to Timothy

- Second Epistle to Timothy

- Epistle to Titus

- Epistle to Philemon

- Epistle to the Hebrews

General epistles

The General or "Catholic" Epistles are those written to the church at large by various writers. (Catholic in this sense simply means universal.)

- Epistle of James, traditionally by James, the brother of Jesus and leader of the Jerusalem church

- First Epistle of Peter, traditionally ascribed to the Apostle Saint Peter

- Second Epistle of Peter, also traditionally ascribed to the Apostle Peter

- First Epistle of John, traditionally ascribed to the Apostle John, son of Zebedee

- Second Epistle of John, also ascribed to the same John

- Third Epistle of John, similarly ascribed to John

- Epistle of Jude, traditionally ascribed to Jude Thomas, brother of Jesus and James

The date and authorship of each of these letters are widely debated.

The Book of Revelation

The final book of the New Testament is the Book of Revelation, traditionally by the Apostle John, son of Zebedee (also known as John of Patmos). The book is also called the Apocalypse of John. It consists primarily of a channeled message from Jesus to seven Christian churches, together with John's dramatic vision of the Last Days, the Second Coming of Christ, and the Final Judgment.

Apocrypha

In ancient times there were dozens or even hundreds of Christian writings which were considered authoritative by some, but not all, ancient churches. These were not ultimately included in the 27-book New Testament canon. These works are considered "apocryphal," and are therefore referred to as the New Testament Apocrypha. Some were deemed by the orthodox churches to be heretical, while others were considered spiritually edifying but not early enough to be included, of dubious authorship, or controversial theologically even if not heretical.

Authorship

The New Testament is a collection of works, and as such was written by multiple authors. The traditional view is that all the books were written by apostles (e.g. Matthew, Paul, Peter, John) or disciples of apostles (such as Luke, Mark, etc). These traditional ascriptions have been rejected by some church authorities as early as the second century, however. In modern times, with the rise of rigorous historical inquiry and textual criticism, the apostolic origin of many of the New Testament books has been called into serious question.

Paul

Seven of the epistles of Paul are now generally accepted by most modern scholars as authentic. These undisputed letters include Romans, First Corinthians, Second Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, First Thessalonians, and Philemon. Opinion about the Epistle to the Colossians and Second Thessalonians is divided. Most critical scholars doubt that Paul wrote the other letters attributed to him. Modern conservative Christian scholars tend to be more willing to accept the traditional ascriptions. However, few serious scholars, Christian or otherwise, still hold that Paul wrote the Letter to the Hebrews.

The authorship of all non-Pauline New Testament books has been disputed in recent times. Ascriptions are largely polarized between conservative Christian and liberal Christian as well as non-Christian experts, making any sort of scholarly consensus all but impossible.

The Gospel writers

The Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, unlike the other New Testament works, have a unique documentary relationship. The traditional view—also supported by a minority of critical scholars—supposes that Matthew was written first, and Mark and Luke drew from it. A smaller group of scholars espouse Lukan priority. The dominant view among critical scholars—the Two-Source Hypothesis—is that the Gospel of Mark was written first, and both Matthew and Luke drew significantly upon Mark and another common source, known as the "Q Source", from Quelle, the German word for "source."

The Gospel of John is thought by traditional Christians to have been written by John, the son of Zebedee. He is also referred to as "the Beloved Disciple," and is particularly important in the Eastern Orthodox tradition. Critical scholarship often takes the view that John's Gospel is the product of a community including formerly Jewish Christians in the late first or early second century, who had been expelled from the Jewish community because of their insistence on the divinity of Jesus and other theological views, which caused them to take an adversarial attitude toward "the Jews."

Other writers

Views about the authors of the other New Testament works—such as the letters purportedly from such figures such as Peter, James, John, and Jude—fall along similar lines. Traditionalists tend to accept the designations as they have been received, while critical scholars often challenge these notions, seeing the works as mistakenly attributed to apostles, or in some case as being "pious forgeries," written in an apostle's name but not actually authored by him.

Date of composition

According to tradition, the earliest of the books were the letters of Paul, and the last books to be written are those attributed to John, who is traditionally said to have been the youngest of the apostles and to have lived to a very old age. Irenaeus of Lyons, c. 185, stated that the Gospels of Matthew and Mark were written while Peter and Paul were preaching in Rome, which would be in the 60s, and Luke was written some time later. Evangelical and traditionalist scholars generally support this dating.

Most critical scholars agree that Paul's letters were the earliest to be written, while doubting that some of the "late" Pauline letters such as Ephesians and Timothy were actually written by Paul. For the Gospels, they tend to date Mark no earlier than 65 and no later than 75. Matthew is dated between 70 and 85. Luke is usually placed within 80 to 95. John's Gospel is the subject of more debate, being dated as early as 85 and as late as the early second century.

A number of variant theories to the above have also been proposed.

Authority

All Christian groups respect the New Testament, but they differ in their understanding of the nature, extent, and relevance of its authority. Views of the authoritativeness of the New Testament often depend on the concept of inspiration, which relates to the role of God in the formation of both the New Testament and the Old Testament. Generally, the greater the direct role of God in one's doctrine of inspiration—and the less one allows for human perspectives interfering with God's revelation—the more one accepts the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy and/or the authoritativeness of the Bible.

- Infallibility relates to the absolute correctness of the Bible in matters of doctrine.

- Inerrancy relates to the absolute correctness of the Bible in factual assertions (including historical and scientific assertions).

- Authoritativeness relates to the correctness of the Bible in questions of practice in morality.

The meaning of all of these concepts depend on the supposition that the text of Bible has been properly interpreted, with consideration for the intention of the text, whether literal history, allegory or poetry, etc.

Canonization

Related to the question of authority is the issue of which books were included in the New Testament: canonization. Here, as with the writing of the texts themselves, the question is related to how directly one believes God or the Holy Spirit was involved in the canonization process. Contrary to popular misconception, the New Testament canon was not decided primarily by large Church council meetings, but rather developed slowly over several centuries. Formal councils and declarations were also involved, however.

In the first three centuries of the Christian church, no New Testament canon was universally recognized. Documents such as some of Paul's letters and various Gospels or apocalypses were read publicly in certain churches, while other documents, including some later judged to be forgeries or heretical, were read in others. One of the earliest attempts at solidifying a canon was made by Marcion, c. 140 C.E., who accepted only a modified version of Luke and ten of Paul's letters, while rejecting the Old Testament entirely. German scholar Adolf Harnack in Origin of the New Testament (1914)[5] argued that the orthodox Church at this time was largely an Old Testament Church without a New Testament canon and that it was against the challenge of Marcionism that the New Testament canon developed. The Muratorian fragment, usually in the late second century, provides the earliest known New Testament canon attributed to mainstream (that is, not Marcionite) Christianity. It is similar, but not identical, to the modern New Testament canon.

The oldest clear endorsement of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John as being the only legitimate Gospels was written c. 180 C.E. by Bishop Irenaeus of Lyon in his polemic Against the Heresies. Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Tertullian (all second century) held the letters of Paul to be on a par with the Hebrew Scriptures as being divinely inspired. Other books were held in high esteem but were gradually relegated to the status of New Testament Apocrypha. Several works were that were given special honor, but did not rise to the status of Scripture. These became known as the works of the Apostolic Fathers, including such documents as the Didache (the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles), the epistles of Ignatius of Antioch, the Shepherd of Hermas, the Martyrdom of Polycarp, and the Epistle of Barnabas.

The Book of Revelation was the most controversial of those books that were finally accepted. Several canon lists by various Church Fathers rejected it. Also, the early church historian Eusebius of Caesaria relates that the church at Rome rejected the letter to the Hebrews on the grounds that it did not believe it to have been written by Paul (Ecclesiastical History 3.3.5).

The "final" New Testament canon was first listed by Athanasius of Alexandria—the leading orthodox figure in the Arian controversy—in 367, in a letter written to his churches in Egypt.[6] Also cited is the Council of Rome of 382 under the authority of Pope Damasus I, but recent scholarship dates the list supposedly associated with this to a century later. Athanasius' list gained increasing recognition until it was accepted at the Third Council of Carthage in 397. Even this council did not settle the matter, however. Certain books continued to be questioned, especially James and Revelation. As late as the sixteenth century, Martin Luther questioned (but in the end did not reject) the Epistle of James, the Epistle of Jude, the Epistle to the Hebrews and the Book of Revelation.

Due to such challenges by Protestants, the Council of Trent reaffirmed the traditional canon as a dogma of the Catholic Church. The vote on the issue was not unanimous, however: 24 yea, 15 nay, 16 abstain.[7] Similar affirmations were made by the Thirty-Nine Articles of 1563 for the Church of England, the Westminster Confession of Faith of 1647 for Calvinism, and the Synod of Jerusalem of 1672 for Greek Orthodoxy.

Language

The common languages spoken by both Jews and Gentiles in the holy land at the time of Jesus were Aramaic, Koine Greek, and to a limited extent Hebrew. The original texts of the New Testament books written mostly or entirely in Koine Greek, the vernacular dialect in first century Roman provinces of the Eastern Mediterranean. They were later translated into other languages, most notably Latin, Syriac, and Coptic.

In the Middle Ages, translation of the New Testament was strongly discouraged by church authorities. The most notable Middle English translation, Wyclif's Bible (1383) was banned by the Oxford Synod in 1408. A Hungarian Hussite Bible appeared in the mid-fifteenth century; and in 1478, a Catalan (Spanish) translation appeared in the dialect of Valencia. In 1521, Martin Luther translated the New Testament from Greek into German, and this version was published in September 1522. William Tyndale's English Bible (1526) met with heavy sanctions, and Tyndale himself was jailed in 1535. The Authorized King James Version is an English translation of the Christian Bible by the Church of England begun in 1604 and first published in 1611. The Counter-Reformation and missionary activity by the Jesuit order led to a large number of sixteenth century Catholic translations into various languages of the New World.

Today there are hundreds if not thousands of translations of the New Testament, covering nearly every language currently spoken.

Notes

- ↑ Clifton J. Allen, The Broadman Bible Commentary: Volume 8 (Broadman Press, 1969).

- ↑ Tertullian, "Chapter XIV" Against Marcion, Book III. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ↑ Tertullian, "Chapter VI" Against Marcion, Book IV. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ↑ Lactantius, "Chapter XX" The Divine Institutes, Book IV. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ↑ Adolf Harnack, "Appendix VI" Origin of the New Testament. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ↑ Athanasius, "Festal Letter XXXIX" Select Works and Letters. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ↑ Bruce A. Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford University Press, 1997), 246.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abingdon Press. The New Interpreter's Bible: General Articles & Introduction, Commentary, & Reflections for Each Book of the Bible, Including the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0687278145

- Allen, Clifton J. The Broadman Bible Commentary: Volume 8. Broadman Press, 1969.

- Brown, Raymond Edward. An Introduction to the New Testament. The Anchor Bible reference library. New York: Doubleday, 1997. ISBN 0385247672

- Ehrman, Bart D. Lost Christianities: The Battle for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0195182491

- Johnson, Luke Timothy. Writings of the New Testament: An Interpretation. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 1986. ISBN 978-0800618865

- Mack, Burton L. Who Wrote the New Testament?: The Making of the Christian Myth. HarperOne, 1996. ISBN 978-0060655181

- Metzger, Bruce M. The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0198269540

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Whose Bible Is It?: A History of the Scriptures Through the Ages. Viking, 2005. ISBN 978-0670033850

External links

All links retrieved November 11, 2022.

- Various versions and translations. www.biblegateway.com

- Duke University's New Testament Gateway. www.ntgateway.com

- Overview of Inerrancy. religioustolerance.org

- Early Christian Writings. www.earlychristianwritings.com

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.