Difference between revisions of "Slovakia" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (69 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}} |

| − | + | {{Infobox Country | |

| − | + | | native_name = {{native name|sk|Slovenská republika|}} | |

| − | {{Infobox Country | + | | conventional_long_name = Slovak Republic |

| − | |native_name | + | | common_name = Slovakia |

| − | |conventional_long_name | + | | image_flag = Flag of Slovakia.svg |

| − | |common_name | + | | image_coat = Coat of Arms of Slovakia.svg |

| − | |image_flag | + | | image_map = EU_location_SVK.png |

| − | |image_coat | + | | map_caption =Map showing the location of Slovakia (dark orange) within the EU |

| − | |image_map | + | | national_anthem = ''[[Nad Tatrou sa blýska]]''<small><br/>"Lightning Over the Tatras"</small><br> |

| − | |map_caption | + | | official_languages = [[Slovak language|Slovak]] |

| − | |national_anthem | + | | unofficial_languages = |

| − | |official_languages | + | | ethnic_groups = 80.7% [[Slovaks]]<br>8.5% [[Hungarians in Slovakia|Hungarians]]<br>2.0% [[Roma in Slovakia|Roma]]<br>0.6% [[Czechs]]<br>0.6% [[Rusyns]]<br>0.1% [[Ukrainians]]<br>0.1% [[Germans]]<br>0.1% [[Poles]]<br>0.1% [[Moravians]]<br>7.2% unspecified<ref>{{cite web |url=https://slovak.statistics.sk/wps/wcm/connect/1f62189f-cc70-454d-9eab-17bdf5e1dc4a/Tab_10_Obyvatelstvo_SR_podla_narodnosti_scitanie_2011_2001_1991.pdf?MOD=AJPERES |title=Tab. 10 Obyvateľstvo SR podľa národnosti – sčítanie 2011, 2001, 1991 |publisher=Portal.statistics.sk |accessdate=October 18, 2019}}</ref> |

| − | | | + | | ethnic_groups_year = 2011 |

| − | | | + | | capital = [[Bratislava]] |

| − | |largest_city | + | | largest_city = capital |

| − | |government_type | + | | government_type = [[Parliamentary republic]] |

| − | |leader_title1 | + | | leader_title1 = [[List of Presidents of Slovakia|President]] |

| − | |leader_title2 | + | | leader_title2 = [[Prime Minister of Slovakia|Prime Minister]] |

| − | |leader_name1 | + | | leader_name1 = [[Zuzana Čaputová]] |

| − | |leader_name2 | + | | leader_name2 = [[Igor Matovič]] |

| − | |accessionEUdate | + | | accessionEUdate = 1 May 2004<ref name=cia>CIA, Slovakia ''The World Factbook''. </ref> |

| − | |area_rank | + | | area_rank = 129th |

| − | |area_magnitude | + | | area_magnitude = 1 E10 |

| − | | | + | | area_km2 = 49,035 |

| − | | | + | | area_sq_mi = 18,932 |

| − | |percent_water | + | | percent_water = negligible |

| − | |population_estimate | + | | population_estimate = {{increase}} 5,458,003<ref>[http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/slovakia-population/ Slovakia Population 2019] ''World Population Review''. Retrieved October 18, 2019.</ref> |

| − | |population_estimate_rank = | + | | population_estimate_rank = 117th |

| − | |population_estimate_year = | + | | population_estimate_year = 2019 |

| − | |population_census | + | | population_census = 5,397,036 |

| − | |population_census_year | + | | population_census_year = 2011 |

| − | | | + | | population_census_rank = |

| − | | | + | | population_density_km2 = 111 |

| − | |population_density_rank | + | | population_density_sq_mi = 287 |

| − | |GDP_PPP | + | | population_density_rank = 88th |

| − | |GDP_PPP_rank | + | | GDP_PPP = $201.799 billion<ref name="IMFWEOSK">[https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2017&ey=2020&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&pr1.x=42&pr1.y=18&c=936&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPPC&grp=0&a= World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019] ''International Monetary Fund''. Retrieved October 18, 2019.</ref> |

| − | |GDP_PPP_year | + | | GDP_PPP_rank = 68th |

| − | |GDP_PPP_per_capita | + | | GDP_PPP_year = 2019 |

| − | |GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank | + | | GDP_PPP_per_capita = $37,021<ref name="IMFWEOSK"/> |

| − | |sovereignty_type | + | | GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 37th |

| − | | | + | | GDP_nominal = $109.863 billion<ref name="IMFWEOSK"/> |

| − | | | + | | GDP_nominal_rank = 61st |

| − | | | + | | GDP_nominal_year = 2019 |

| − | | | + | | GDP_nominal_per_capita = $20,155<ref name="IMFWEOSK"/> |

| − | | | + | | GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 41st |

| − | | | + | | sovereignty_type = [[Independence]] |

| − | + | | established_event1 = {{nowrap|from [[Austria–Hungary]]}}<br><small>as [[First Czechoslovak Republic|Czechoslovakia]]</small> | |

| − | |currency | + | | established_date1 = 28 October 1918 |

| − | |currency_code | + | | established_event2 = {{nowrap|[[Dissolution of Czechoslovakia|from]] [[Czech and Slovak Federal Republic|Czechoslovakia]]}} |

| − | |country_code | + | | established_date2 = 1 January 1993<sup>1</sup> |

| − | |time_zone | + | | Gini_year = 2017 |

| − | |utc_offset | + | | Gini_change = decrease <!--increase/decrease/steady—> |

| − | |time_zone_DST | + | | Gini = 23.2<ref name=eurogini>[https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tessi190&plugin=1 Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey] ''Eurostat''. Retrieved October 18, 2019.</ref> <!--number only—> |

| − | |utc_offset_DST | + | | currency = Euro ([[Euro sign|€]])<sup>2</sup> |

| − | |cctld | + | | currency_code = |

| − | |calling_code | + | | country_code = |

| − | |footnotes | + | | time_zone = [[Central European Time|CET]] |

| − | <sup>1</sup> [[Czechoslovakia]] split into the | + | | utc_offset = +1 |

| − | <sup>2</sup> Also [[.eu]], shared with other | + | | time_zone_DST = [[Central European Summer Time|CEST]] |

| − | <sup> | + | | utc_offset_DST = +2 |

| + | | demonym = [[Slovaks|Slovak]] | ||

| + | | drives_on = right | ||

| + | | cctld = [[.sk]]<sup>3</sup> | ||

| + | | calling_code = [[Telephone numbers in Slovakia|+421]]<sup>4</sup> | ||

| + | | footnotes = <sup>1</sup> [[Czechoslovakia]] split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia; see [[Dissolution of Czechoslovakia|Velvet Divorce]].<br/><sup>2</sup> Before 2009: [[Slovak koruna|Slovak Koruna]] <br/><sup>3</sup> Also [[.eu]], shared with other European Union member states.<br/><sup>4</sup> Shared code 42 with Czech Republic until 1997. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Slovakia''' (''Slovensko'') is a landlocked country in Central [[Europe]] with a population of over five million, bordering the [[Czech Republic]] and [[Austria]] in the West, [[Poland]] in the North, the [[Ukraine]] in the East, and [[Hungary]] in the South. Its origins date to [[Celts|Celtic]] settlements in the fifth century. It has a rich ethnic makeup, including [[Roman Empire|Romans]], Germanic tribes, Slavs, Hungarians, [[Mongol Empire|Mongols]], [[Jew]]s, and [[Turkish people|Turks]]. The glorious moments in its history occurred during King [[Samo]]'s Empire, when the Slavs stopped invading neighboring tribes in favor of developing an [[agriculture|agricultural]] society and formed the first state; the Great Moravian Empire, when [[Christianity]] and the first script were introduced, and the National Revival Movement. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| + | The eight hundred years of Hungarian oppression was openly confronted during the [[Revolutions and Revivals of 1848|Revolutions of 1848]] in Europe, albeit unsuccessfully. Historical similarities with the [[Czech Republic]] drew the two countries together in the wake of escalated [[Hungary|Magyarization]] in the second half of the nineteenth century, and, ultimately, toward a joint state. Slovakia chose autonomy and aligned itself with the [[Fascism|fascist]] [[Germany]] during [[World War II]], as an alternative to a direct German control within the Protectorate of [[Bohemia]] and [[Moravia]]. The fall of [[communism]] in 1989 precipitated the unresolved issues between Czechs and Slovaks, and Slovakia declared independence in 1993. It was admitted to the [[European Union]] in 2004. The largest city is its capital, [[Bratislava]]. | ||

| + | == History == | ||

| + | Beginning around 450 B.C.E., Slovakia was settled by [[Celts]], who built powerful settlements in [[Bratislava]] and Liptov. [[Silver]] coins bearing the names of Celtic kings are the source of the first archaeologically proven use of an alphabet. Around 6 C.E., the expanding [[Roman Empire]] began establishing and maintaining a chain of outposts around the [[Danube]]. The [[barbarian]] Kingdom of Vannius, founded by the Germanic tribe of Quadi, existed in western and central Slovakia between 20 to 50 C.E. | ||

| − | + | The Slavic tribes settled in Slovakia in the fifth century, with the most glorious periods being those of the King [[Samo]]’s Empire and the Principality of Nitra. The latter became part of the Great Moravian Empire. | |

| − | The | ||

| + | === King Samo’s Empire (623-658) === | ||

| + | Slavs inhabiting Slovakia were under the constant threat of [[nomad]]ic Avars until their defeat in 623, due in part to the Frankish merchant Samo. Being a wealthy man operating in the territory of Central and [[Eastern Europe]], Samo realized that the Slavs, given to feuds and animosity, would benefit greatly from a shipment of weapons, so he armed them and led them to the war against the Avars. The Slavs responded by electing him their king. Samo’s Empire was the first known organized community of Slavs, operating as a confederation of more or less independent principalities in the fashion of the Franks. Samo is credited for spearheading the process of the pacification of Slavic tribes, who were thus able to refocus their energies on [[agriculture]] and gave up looting expeditions. After his death, the empire dissolved into principalities, which were later consolidated within the Great Moravian Empire. | ||

| − | === | + | === The Great Moravian Empire (833-906) === |

| − | + | A proto-Slovak state, the Principality of Nitra, rose in the eighth century. Its ruler, Pribina, ordered consecration of the first [[Christianity|Christian]] church in Slovakia in 828. Together with neighboring [[Moravia]], the principality formed the core of the Great Moravian Empire from 833, when the first documented prince of Great Moravia, Mojmír I (830-846), conquered the Principality of Nitra and unseated Pribina. | |

| − | + | The empire was booming under [[Rastislav|Prince Rastislav]] (846-870), who, aware of the importance of [[Christianity]] to the strengthening of his rule, acceptance by the advanced [[Europea]]n countries, and political backing by the [[Byzantine Empire]], asked the Byzantine emperor to send a bishop that would spread Christianity in the language understandable to local Slavs. Brothers [[Cyril and Methodius]], Greek by nationality, were dispatched in 863, but before they arrived, the extremely-learned Cyril put together a Slavic alphabet, Glagolitic, and began translating the Scriptures. The language they used was known as Old Slavonic; it resembled the vernacular used in Great Moravia and became the language of worship. The brothers taught their disciples the new language and the alphabet, giving rise to the first works of Slavonic literature. However, Bavarian bishops found their work disrupting and accused them of spreading heresy in a language that was not [[Latin]], prompting the brothers to go to Rome to defend themselves to the [[pope]], who was forced to allow the usage of the language. It played a great role in the history of Slavic languages and eventually evolved into [[Old Church Slavonic]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | Under Svatopluk (870-894), the empire occupied the areas of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, southwestern Poland, southeastern Germany, Hungary, northern and eastern Austria, and western Romania, totaling 350,000 square kilometers with an estimated population of 1.5 million. It was the first joint (proto-)state of Czechs and Slovaks. A crossroads of major European trading routes, it was on par with the neighboring Frankish Empire, with a developed judicial system. It assimilated cultures of the West, penetrating from Western Europe, and the East, symbolized by Christianity spreading from the | + | Under [[Svatopluk]] (870-894), the empire occupied the areas of the [[Czech Republic]], Slovakia, southwestern [[Poland]], southeastern [[Germany]], [[Hungary]], northern and eastern [[Austria]], and western [[Romania]], totaling 350,000 square kilometers with an estimated population of 1.5 million. It was the first joint (proto-)state of Czechs and Slovaks. A crossroads of major European trading routes, it was on par with the neighboring Frankish Empire, with a developed judicial system. It assimilated cultures of the West, penetrating from Western Europe, and the East, symbolized by Christianity spreading from the [[Byzantine Empire]]. The cities Nitra and [[Bratislava]] were among its major centers. |

| − | + | Svätopluk’s successor Mojmír II (894-906) faced attacks from both the Franks and nomadic Hungarian tribes, and in 906, the Hungarians conquered it, which some historians attribute to the uncontrolled population growth of Hungarians in the southern parts of the empire without safeguarding the same for the Slavic citizens. The Slavs purportedly hoped that the Hungarians would assimilate into the Slavic state. Czechs and Slovaks were to be disjoined for a thousand years, until 1918, when the federal [[Czechoslovakia]] would be established. | |

| + | == Kingdom of Hungary == | ||

| + | [[Image:TrencinCastle.JPG|250px|right|thumb|Trenčín Castle]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Slovakia Oravsky Podzamok.jpg|250px|right|thumb|Orava Castle]] | ||

| + | [[File:Castle Bojnice SK.jpg|250px|thumb|Bojnice Castle, the only one of its design in Central Europe]] | ||

| − | + | The [[Hungary|Magyars]] gradually occupied Slovakia, which, nevertheless, retained its privileges in this new state because of its high level of economic and cultural development. For almost two centuries, Slovakia was ruled autonomously as the Principality of Nitra within the Kingdom of Hungary. Slovak settlements extended to the northern half of present-day Hungary, while Hungarians later settled down in the southern part of Slovakia. The ethnic composition became more diverse with the arrival of the Carpathian Germans in the thirteenth century, [[Vlachs]] in the fourteenth century, and [[Jew]]s. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | A huge population loss resulted from the invasion of the [[Mongol Empire|Mongols]] in 1241 and the subsequent [[famine]]. However, medieval Slovakia was characterized rather by burgeoning towns, construction of numerous stone [[castle]]s, and the development of [[art]]s. In 1467, [[Matthias Corvinus I|King Matthias Corvinus]] established the first [[university]] in [[Bratislava]], although the institution was short-lived. | ||

| − | After the [[Ottoman Empire]] | + | After the [[Ottoman Empire]] began expanding into Hungary and invaded [[Budapest]] in the early sixteenth century, the center of the Kingdom of Hungary shifted toward Slovakia, and [[Bratislava]] (''Pressburg'', ''Pressporek'', ''Pozsonium'' or ''Pozsony'') became the capital in 1536. The Ottoman wars and frequent insurrections against the [[Habsburg]] Monarchy inflicted a great deal of destruction, especially in rural areas. |

| − | + | As the Turks retreated from Hungary in the eighteenth century, Slovakia's standing within the kingdom decreased, although Bratislava retained its position of the capital city of Hungary until 1848, when the capital was moved back to Budapest. | |

| − | |||

| + | === National Revival Movement === | ||

| + | The first attempt to enact the literary Slovak language (based on the western Slovakian dialect) came in 1787 by Anton Bernolák, but it was not accepted by Slovak Protestants. Only the 1843 version of the language, authored by Štúr, Hurban, and Hodža and based on the central Slovakian dialect, won the support of general public. Lacking a state structure of its own, Slovakia was forced to enlist assistance with the revival cause from similar ideological movements in Hungary. However, Hungary in the 1840s changed course toward a quest for a unified state independent of [[Austria]], which was not to be endorsed by Slovaks, who had been suppressed by Hungarians since the outset of the Kingdom of Hungary. | ||

| + | In May 1848, ''Requests of the Slovak Nation'' were drafted calling for the use of the Slovak language in schools and public offices, but neither Hungary nor Austria took them seriously. Nor did the European [[Revolutions and Revivals of 1848|Revolutions of 1848]] bring about a turnaround, as Hungary stepped up repressions of non-Hungarian nationalities, particularly after the forming of the Dual Monarchy, whereby Hungary became independent of [[Vienna]]. In the 1870s, Magyars closed down Slovak [[high school]]s and the national institute for the promotion of Slovak culture (Matica slovenská) as [[Hungary|Magyarization]] was forced on Slovaks in all aspects of life. This continued until the emergence of [[Czechoslovakia]] in 1918. Still, this was an important period in the life of the nation, as it accelerated the breakdown of [[feudalism]] and foreshadowed the emergence of an independent Slovak state later on. It was carried out by intelligentsia, mostly of non-aristocratic background, and as such, the movement was thus more [[democracy|democratic]] by nature. | ||

| − | + | Czechs, on the other hand, had to deal with Germanization, which ultimately brought the two nations together. This was also fueled by Slovakia's disappointment with Hungarian reformists who were increasingly unwilling to fit the Slovak agenda within their own, and later crystallized into the idea of a joint state of Czechs and Slovaks, promulgated by [[Milan Rastislav Štefánik]], [[Tomas Garrigue Masaryk]], and [[Eduard Beneš]]. However, the multi-ethnic makeup of the [[Austria-Hungary|Austro-Hungarian Empire]] did not allow for a free pursuit of these goals; therefore, sympathies of the outside world had to be secured—Czechoslovak Legions as well as the Czechoslovak National Council (1916) were formed, and ties were made with [[Europe]]an statesmen. In 1915, the Cleveland Agreement laid out an equal position of both countries within the future Czecho-Slovak federal republic. | |

| + | ==Twentieth century== | ||

===Czechoslovak Republic=== | ===Czechoslovak Republic=== | ||

| − | In 1918, Slovakia joined the regions of [[Bohemia]] and | + | [[Image:Bratislava View From Petrzalka Old City Part.jpg|240px|thumb|Bratislava Old Town]] |

| + | In 1918, Slovakia joined the regions of [[Bohemia]] and neighboring [[Moravia]] to form [[Czechoslovakia]]. During the chaos following the breakup of [[Austria-Hungary|Austro-Hungarian Empire]], it was attacked in 1919 by the provisional Hungarian Soviet Republic and one-third of its territory temporarily became the Slovak Soviet Republic. | ||

| − | Although the Constitution of the Czechoslovak Republic | + | Although the 1920 Constitution of the Czechoslovak Republic guaranteed certain country-specific rights and privileges to Slovakia, they were not fully respected, in contradiction with the Pittsburgh Agreement of 1918 that stipulated autonomous rights for Slovaks, including the right to the Slovak language as the official language of Slovakia. The policy was based on Czechoslovakism, a doctrine that originated during [[World War I]] in an effort to create a joint state of Czechs and Slovaks by means of unification, especially of the two languages. A large number of Czechs came to alleviate Slovakia’s shortage of managers and civil servants, although this became a source of controversy during time when the Czechs continued to control the lucrative posts even after the Slovak intelligentsia was brought up. Frustration gave in to an anti-government demonstration staged by [[Andrej Hlinka]], who formed Hlinka’s Slovak People’s Party (HSĽS) as a platform to enforce demands for a separate parliament, administrative bodies, judiciary, and the official language. His party played a major role in the subsequent Slovak State. Nevertheless, historians agree that the existence of Czechoslovakia has benefited Slovakia greatly in that it allowed it to almost close the economic and cultural gap with its western neighbor. |

| − | + | Between [[World War I]] and [[World War II]], the existence of the democratic and prosperous [[Czechoslovakia]] was jeopardized by revisionist governments of [[Germany]] and [[Hungary]], until it was finally split by the [[Munich Agreement]] of 1938. | |

| − | === | + | ===Slovak State=== |

| − | + | The infamous Munich Treaty of September 1938 resulted in the unification of most political parties around the Party of Slovak National Unity (HSĽS)-sponsored demand for the political autonomy of Slovakia and thus the decentralization of the executive and legislative power of [[Czechoslovakia]]. The [[Prague]] government of General Jan Syrovy did not oppose these demands, and the acting head of the HSĽS, [[Jozef Tiso]], was appointed as minister for the administration of Slovakia. On November 22, 1938, Slovakia’s political autonomy was signed into law, although part of its territory was taken over by Hungary, and Germany occupied portions of Bratislava. Democratic reforms quickly gave in to an authoritarian rule marked by political censorship and a forceful unification of political parties and social organizations. The HSĽS leadership was gradually overpowered by its radical wing vying for no less than absolute independence of the country, to which the Czechoslovak government responded with intervention and internment of 250 Slovak radicals. To Slovakia, this felt as an attack on its autonomy. | |

| − | + | In the meantime, [[Adolf Hitler|Hitler]] took advantage of Slovakia's aspirations and invited Tiso to [[Berlin]] to coerce him into the secession of Slovakia and thus the liquidation of Czechoslovakia. Should Tiso disagree, Slovakia would be given to [[Hungary]]. On March 14, 1939, the Slovak Parliament gave a green light to the Slovak State, with the new government headed by Tiso. However, Czechoslovakia did not cease to exist; it continued its existence via an exiled government and armed forces as well as foreign embassies. At the same time, the independent Slovakia had its hands tied by agreements with Germany and generally had no choice but to align its economy with Hitler's plans, who found it all too easy to control the country headed by the [[corruption|corrupt]] leadership backed by the [[Roman Catholic Church]]. Slovakia even had its own currency, but because Germany did not honor the economic agreements and, paradoxically, incurred a large debt, the Slovak government resorted to anti-[[Jew|Jewish]] measures to replenish its coffers. In September 1940, the government ordered registration of the Jewish property, which was then confiscated, totaling 3,187,657 Slovak crowns. | |

| − | + | Despite plundering by Germany, Slovakia boasted one of the most stable economies among neighboring countries. This was reinforced by the statement used by state officials that Slovakia remains to be an “oasis of affluence amid starving and bleeding Europe.”<ref>Dušan Mihálik, [http://www.prave-spektrum.sk/article.php?529 "Slovenský štát – ekonomický zázrak?"] ''Prave Spektrum Magazine'', February 26, 2007. Retrieved October 18, 2019.</ref> The tendency was toward [[centralization]], mergers of businesses and their subsequent state control, and [[nationalization]] of natural resources. Employment was at its highest, mostly as a consequence of the resettlement of 20,000 Czech civil servants and the elimination of Jews from the economic life and later on their transport to [[Nazism|Nazi]] [[concentration camp]]s. Education, science, and arts underwent revitalization. | |

| − | + | The plight of Slovak Jews under the Slovak state continues to haunt Slovakia’s past, and the anti-Jewish laws of 1940, mandating Aryanization, prove that [[anti-Semitism]] ran amok prior to deportations. Jews were prohibited from the acquisition of businesses, were allowed to lease and handle immovables and movables only with a prior written permission, and their trade licenses were revised and businesses marked as Jewish. In the next batch of legislation, the government assigned itself the right to adopt all measures required to exclude Jews from the Slovak economic and social life and transfer Jewish ownership to Christians, and, finally, to deport them, to be paid with the proceeds from the confiscated Jewish property. These laws had an impact on Slovakia’s economy, as many people, especially the executors of the Aryanization laws, pocketed the Jewish wealth and occupied their vacated apartments. | |

| − | + | ===Slovak National Uprising=== | |

| + | In 1943, the Slovak state began experiencing severe problems with supply amid rampant [[corruption]] and [[usury]]. The “Oasis of Affluence” was losing its luster, and even the fact that [[Germany]] and other neighboring countries were under greater deprivation could not stem the growing discontent. Politicians with anti-German leanings publicly acknowledged the existence of [[Czechoslovakia]] in the Christmas Agreement and proclaimed allegiance to the joint state of Czechs and Slovaks against Hitler’s Germany. Crucial to the agreement was the preparation of an armed conflict and removal of the HSĽS from power. | ||

| − | + | Pro-[[democracy|democratic]] citizens began participating in the resistance movement, and two-thirds of the Slovak currency was made available to the cause. Weaponry, which at one time came in handy to the fascist Germany, was transferred surreptitiously to the designated centers of the uprising. In August 1944, the [[United States|U.S.]] Air Force bombed a state-owned refinery in Central Slovakia despite multiple warnings sent to the exiled Czechoslovak government in [[London]] that the refinery was crucial to the uprising-in-the-works. | |

| − | + | The Slovak National Uprising broke out on August 29, 1944, and a few days later the joint state of Czechs and Slovaks was to be restored as a federal structure. [[Black market]] practices and corruption that had been tolerated by the government and paramilitary Hlinka's Guard (''Hlinkova Garda'') were being reversed. The final stage of the uprising was in the spirit of partisan activities rather than open resistance. | |

| − | + | ===After World War II=== | |

| + | After [[World War II]], Slovakia became part of [[Czechoslovakia]] as a satellite of the [[Communism|communist]] [[Soviet Union]] and its [[Warsaw Pact]]. In 1968, Czechoslovakia courted liberation from the communist grip in the events referred to as the [[Prague Spring]], when it made an attempt to reform the regime from within and embark on the path toward liberalization and a multi-party system. Slovak-born [[Alexander Dubcek]] became a symbol of these developments. However, the Warsaw Pact armies invaded and crushed Czechoslovakia's hopes under the tanks as the Western world watched. In 1969, Czechoslovakia was reorganized as a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic. | ||

| − | + | The end of the infamous 40 years finally came in 1989, during the peaceful Velvet Revolution. Four years later, on January 1, 1993, the country was dissolved once again into two successor states. Slovakia and the Czech Republic went their own ways after the Velvet Divorce but have remained close partners. Slovakia joined the [[European Union]] in May 2004. | |

| − | + | ==Geography== | |

| + | [[Image:Slovakia_topo.jpg|250px|right|thumb|Relief of Slovakia]] | ||

| + | [[Image:STRBSKE PLESO.jpg|thumb|500px|righ|High Tatras]] | ||

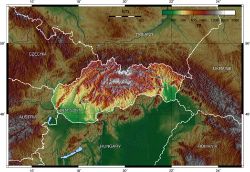

| + | Located at the heart of Europe, Slovakia shares borders with [[Poland]] to the north, the [[Czech Republic]] in the northwest, [[Austria]] in the southwest, [[Hungary]] to the south, and the [[Ukraine]] to the east. It is a mountainous country with almost 80 percent of its total area above 2,460 feet (750 meters). It encompasses 48,845 square kilometers; 48,800 being land and the remaining 45 square kilometers of water. This makes it approximately twice the size of the [[United States|U.S.]] state of [[New Hampshire]]. | ||

| − | + | The Slovak landscape is crowned by the [[Carpathian Mountains]] extending across most of the northern half of the country. The most notable range is the Tatras, home to scenic lakes and valleys as well as the highest peak, the Gerlachovský štít (2,655 meters/8,711 feet). South of the Low Tatras the land drops to a fertile plain stretching to the [[Danube River]]. | |

| − | + | [[Forest]]s, especially of beech and spruce, cover 40 percent of the country. Wildlife is abundant in the valleys of the High Tatra and includes [[bear]]s, [[wolf|wolves]], [[lynx]]es, [[marmot]]s, [[chamois]], [[deer]], mink]] and otter. Birdlife includes [[eagle]]s, [[hawk]]s, [[vulture]]s, [[pheasant]]s, [[partridge]]s, [[duck]]s, wild [[goose|geese]], [[stork]]s, and [[grouse]]. | |

| − | + | The [[Danube]], Váh, and Hron are the largest [[river]]s. The [[climate]] is temperate, with relatively warm summers and cold, cloudy and humid winters. | |

| − | + | ==Demographics== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Kosice (Slovakia) - St. Elizabeth's Catedral 1.jpg|250px|right|thumb|St. Elizabeth’s Cathedral]] | |

| − | + | Slovaks form the majority of the population, with Hungarians being the largest ethnic minority, concentrated in the southern and eastern regions of the country. Several municipalities, such as Dunajská Streda, Komárno, Šahy, and Želiezovce, are majority Hungarian. Other ethnic groups include [[Roma]], Czechs, Ruthenians, [[Ukraine|Ukrainians]] and Germans. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The majority of Slovaks identify themselves with [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholicism]], followed by [[Protestant|Lutheranism]] and Greek Catholicism. Only around 2,000 [[Jew]]s remain of the 120,000-strong pre-[[Holocaust]] population. | |

| − | + | The official language is Slovak, a member of the Slavic language family, but Hungarian is widely spoken in the south and enjoys the same status as does Slovak language in some regions. | |

| − | + | == Society and culture == | |

| + | The development of Slovak culture reflects the country’s rich folk tradition, in addition to the influence of broader [[Europe]]an trends. The impact of centuries of cultural repression and control by foreign governments is also evident in much of Slovakia’s art, literature, and music. | ||

| − | + | A national movement began in the late eighteenth century aimed at fostering Slovak culture and identity. One of its leaders was Anton Bernolk, a [[Society of Jesus|Jesuit]] priest who codified a Slovak literary language based on dialects used in western Slovakia. In the nineteenth century, [[Protestantism|Protestant]] leaders [[Jan Kollar]] and [[Pavel Josef Šafařík|Pavel Safarik]] developed a form of written Slovak that combined the dialects used in central Slovakia and the Czech lands. | |

| − | + | [[Poetry]] remained an important literary form into the twentieth century, and was used by some Slovak writers to address the experience of [[World War II]] and the rise of [[communism]]. During the communist period, Slovak literary culture suffered from heavy governmental control. | |

| − | + | An important aspect of cultural life in Slovakia is its music. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a national musical tradition began to develop around Slovakia’s impressive folk heritage. Modern Slovak music draws from both classical and folk styles. Traditional Slovakian music is one of the most original of Slavic and European [[folklore]]. National Slovakian music was heavily influenced by liturgical and chamber music. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Politics== | ==Politics== | ||

| + | Slovakia is a parliamentary democratic republic with a multi-party system. The head of state is the president, elected in a direct popular vote for a five-year term. Executive power is concentrated in the hands of the prime minister, who is most frequently the leader of the winning party and has to form a majority coalition in the parliament. The prime minister is appointed by the president. The remainder of the cabinet is appointed by the president on the recommendation of the prime minister. | ||

| − | + | The highest legislative body is the 150-seat unicameral National Council of the Slovak Republic (''Národná rada Slovenskej republiky''). Delegates are elected for a four-year term on the basis of a proportional representation. The Constitutional Court (''Ústavný súd'') is the highest judicial body; its 13 members are appointed by the president. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Slovakia | + | Slovakia joined the [[European Union]] on May 1, 2004, and [[NATO]] on March 29, 2004. As a member of the [[United Nations]] since 1993, it was elected for the first time to a two-year term on the [[United Nations Security Council]] on October 10, 2005. |

==Administrative divisions== | ==Administrative divisions== | ||

| − | + | Slovakia is subdivided into eight regions/countries (''kraje'') named after their respective principal cities. The regions enjoy a degree of autonomy. | |

[[Image:Slovakiakrajenumbers.png|right|350px]] | [[Image:Slovakiakrajenumbers.png|right|350px]] | ||

| − | # Bratislava Region | + | # Bratislava Region ''(Bratislavský kraj)'' (capital [[Bratislava]]) |

| − | # Trnava Region | + | # Trnava Region ''(Trnavský kraj)'' (capital Trnava) |

| − | # Trenčín Region | + | # Trenčín Region ''(Trenčiansky kraj)'' (capital Trenčín) |

| − | # Nitra Region | + | # Nitra Region ''(Nitriansky kraj)'' (capital Nitra) |

| − | # Žilina Region | + | # Žilina Region ''(Žilinský kraj)'' (capital Žilina) |

| − | # Banská Bystrica Region | + | # Banská Bystrica Region ''(Banskobystrický kraj)'' (capital Banská Bystrica) |

| − | # Prešov Region | + | # Prešov Region ''(Prešovský kraj)'' (capital Prešov) |

| − | # Košice Region | + | # Košice Region ''(Košický kraj)'' (capital Košice) |

(the word ''kraj'' can be replaced by ''samosprávny kraj'' or by ''VÚC'' in each case) | (the word ''kraj'' can be replaced by ''samosprávny kraj'' or by ''VÚC'' in each case) | ||

| − | The | + | The regions are further subdivided into 79 districts (''okresy''). |

| − | In terms of | + | In terms of economy and unemployment rate, the western regions fare better than the eastern regions. |

==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

| + | Slovakia has transitioned from the centrally planned economy to a modern market economy. Major privatizations are completed, the banking sector is almost completely in private hands, and foreign investment has risen. It now has a developed, high-income economy, although the country has difficulties addressing regional imbalances in wealth and employment. The country adopted the [[Euro]] currency in 2009. | ||

| − | + | The Slovak government encourages foreign investment, since it is one of the driving forces of the economy. Slovakia is an attractive country for foreign investors mainly because of its low wages, low tax rates, well educated labor force, favorable geographic location in the heart of Central Europe, strong political stability, and good international relations reinforced by the country's accession to the European Union. Some regions, mostly at the east of Slovakia have failed to attract major investment, which has aggravated regional disparities in many economic and social areas. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Slovakia is | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * Axworthy, Mark. ''Axis Slovakia: Hitler's Slavic Wedge, 1938-1945''. Bayside, NY: Axis Europa Books, 2002. ISBN 1891227416 | ||

| + | * Bartl, Július. ''Slovak History: Chronology and Lexicon''. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0865164444 | ||

| + | * Downs, Jim, ''World War II: OSS Tragedy in Slovakia''. Oceanside, CA: Liefrinck, 2002. ISBN 0971748209 | ||

| + | * Drobná, Ol̕ga, Eduard Drobný and Magdalena Gocnikova. ''Slovakia: The Heart of Europe''. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0865163197 | ||

| + | * Goldman, Minton F. ''Slovakia Since Independence: A Struggle for Democracy''. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1999. ISBN 0275961893 | ||

| + | * Horn, Alfred. ''Czech & Slovak Republics''. Hong Kong: APA Publications; Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993. ISBN 0395659876 | ||

| + | * Humphreys, Rob, and Slawomir Adamczak. ''The Rough Guide to the Czech and Slovak Republics''. New York: Rough Guides, 2006. ISBN 1843535254 | ||

| + | * Jacobs, Michael. ''Czech & Slovak Republics''. London: A & C Black, 1999. ISBN 071364429X | ||

| + | * Junas, Lil. ''My Slovakia: An American's View''. Matice Slovenskej, 2001. ISBN 8070906227 | ||

| + | * Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. ''A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival''. New York, St. Martin's Press, 1995. ISBN 0312104030 | ||

| + | * Lazišt̕an, Eugen, Fedor Mikovič, and Ivan Kučma. ''Slovakia: A Photographic Odyssey''. Wauconda, IL, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2001. ISBN 0865165173 | ||

| + | * Schuster, Rudolf, and M. Mark Stolarik. ''The Slovak Republic: A Decade of Independence, 1993-2002''. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2003. ISBN 0865165688 | ||

| + | * Wilson, Neil, and Richard Nebeský. ''Czech & Slovak Republics''. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet, 2001. ISBN 1864502126 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 30, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | * [http://www.nrsr.sk/default.aspx?lang=en National Council of the Slovak Republic] | ||

| + | * [http://www.prezident.sk Slovak Presidential Office] | ||

| + | * [http://www.slovakia.org Slovakia.org: Guide to the Slovak Republic] | ||

| + | * [http://www.discoverslovakia.info/en-index.php Discover Slovakia] | ||

| + | * [https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/slovakia-visa/ Slovakia Visa Application Requirements] | ||

| + | * [https://tripedia.info/location/europe/slovakia/ Slovakia Travel Guide] | ||

{{Countries of Europe}} | {{Countries of Europe}} | ||

{{EU members}} | {{EU members}} | ||

| − | |||

{{NATO}} | {{NATO}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {{credit|104736234}} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Europe]] | |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Geography]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Countries]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 14:57, 27 April 2023

| Slovenská republika Slovak Republic |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Nad Tatrou sa blýska "Lightning Over the Tatras" |

||||||

| Map showing the location of Slovakia (dark orange) within the EU

|

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Bratislava | |||||

| Official languages | Slovak | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2011) | 80.7% Slovaks 8.5% Hungarians 2.0% Roma 0.6% Czechs 0.6% Rusyns 0.1% Ukrainians 0.1% Germans 0.1% Poles 0.1% Moravians 7.2% unspecified[1] |

|||||

| Demonym | Slovak | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| - | President | Zuzana Čaputová | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Igor Matovič | ||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | from Austria–Hungary as Czechoslovakia |

28 October 1918 | ||||

| - | from Czechoslovakia | 1 January 19931 | ||||

| EU accession | 1 May 2004[2] | |||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 49,035 km² (129th) 18,932 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | negligible | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2019 estimate | |||||

| - | 2011 census | 5,397,036 | ||||

| - | Density | 111/km² (88th) 287/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $201.799 billion[4] (68th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $37,021[4] (37th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $109.863 billion[4] (61st) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $20,155[4] (41st) | ||||

| Gini (2017) | 23.2[5] | |||||

| Currency | Euro (€)2 | |||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .sk3 | |||||

| Calling code | [[++4214]] | |||||

| 1 Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia; see Velvet Divorce. 2 Before 2009: Slovak Koruna 3 Also .eu, shared with other European Union member states. 4 Shared code 42 with Czech Republic until 1997. |

||||||

Slovakia (Slovensko) is a landlocked country in Central Europe with a population of over five million, bordering the Czech Republic and Austria in the West, Poland in the North, the Ukraine in the East, and Hungary in the South. Its origins date to Celtic settlements in the fifth century. It has a rich ethnic makeup, including Romans, Germanic tribes, Slavs, Hungarians, Mongols, Jews, and Turks. The glorious moments in its history occurred during King Samo's Empire, when the Slavs stopped invading neighboring tribes in favor of developing an agricultural society and formed the first state; the Great Moravian Empire, when Christianity and the first script were introduced, and the National Revival Movement.

The eight hundred years of Hungarian oppression was openly confronted during the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe, albeit unsuccessfully. Historical similarities with the Czech Republic drew the two countries together in the wake of escalated Magyarization in the second half of the nineteenth century, and, ultimately, toward a joint state. Slovakia chose autonomy and aligned itself with the fascist Germany during World War II, as an alternative to a direct German control within the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The fall of communism in 1989 precipitated the unresolved issues between Czechs and Slovaks, and Slovakia declared independence in 1993. It was admitted to the European Union in 2004. The largest city is its capital, Bratislava.

History

Beginning around 450 B.C.E., Slovakia was settled by Celts, who built powerful settlements in Bratislava and Liptov. Silver coins bearing the names of Celtic kings are the source of the first archaeologically proven use of an alphabet. Around 6 C.E., the expanding Roman Empire began establishing and maintaining a chain of outposts around the Danube. The barbarian Kingdom of Vannius, founded by the Germanic tribe of Quadi, existed in western and central Slovakia between 20 to 50 C.E.

The Slavic tribes settled in Slovakia in the fifth century, with the most glorious periods being those of the King Samo’s Empire and the Principality of Nitra. The latter became part of the Great Moravian Empire.

King Samo’s Empire (623-658)

Slavs inhabiting Slovakia were under the constant threat of nomadic Avars until their defeat in 623, due in part to the Frankish merchant Samo. Being a wealthy man operating in the territory of Central and Eastern Europe, Samo realized that the Slavs, given to feuds and animosity, would benefit greatly from a shipment of weapons, so he armed them and led them to the war against the Avars. The Slavs responded by electing him their king. Samo’s Empire was the first known organized community of Slavs, operating as a confederation of more or less independent principalities in the fashion of the Franks. Samo is credited for spearheading the process of the pacification of Slavic tribes, who were thus able to refocus their energies on agriculture and gave up looting expeditions. After his death, the empire dissolved into principalities, which were later consolidated within the Great Moravian Empire.

The Great Moravian Empire (833-906)

A proto-Slovak state, the Principality of Nitra, rose in the eighth century. Its ruler, Pribina, ordered consecration of the first Christian church in Slovakia in 828. Together with neighboring Moravia, the principality formed the core of the Great Moravian Empire from 833, when the first documented prince of Great Moravia, Mojmír I (830-846), conquered the Principality of Nitra and unseated Pribina.

The empire was booming under Prince Rastislav (846-870), who, aware of the importance of Christianity to the strengthening of his rule, acceptance by the advanced European countries, and political backing by the Byzantine Empire, asked the Byzantine emperor to send a bishop that would spread Christianity in the language understandable to local Slavs. Brothers Cyril and Methodius, Greek by nationality, were dispatched in 863, but before they arrived, the extremely-learned Cyril put together a Slavic alphabet, Glagolitic, and began translating the Scriptures. The language they used was known as Old Slavonic; it resembled the vernacular used in Great Moravia and became the language of worship. The brothers taught their disciples the new language and the alphabet, giving rise to the first works of Slavonic literature. However, Bavarian bishops found their work disrupting and accused them of spreading heresy in a language that was not Latin, prompting the brothers to go to Rome to defend themselves to the pope, who was forced to allow the usage of the language. It played a great role in the history of Slavic languages and eventually evolved into Old Church Slavonic.

Under Svatopluk (870-894), the empire occupied the areas of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, southwestern Poland, southeastern Germany, Hungary, northern and eastern Austria, and western Romania, totaling 350,000 square kilometers with an estimated population of 1.5 million. It was the first joint (proto-)state of Czechs and Slovaks. A crossroads of major European trading routes, it was on par with the neighboring Frankish Empire, with a developed judicial system. It assimilated cultures of the West, penetrating from Western Europe, and the East, symbolized by Christianity spreading from the Byzantine Empire. The cities Nitra and Bratislava were among its major centers.

Svätopluk’s successor Mojmír II (894-906) faced attacks from both the Franks and nomadic Hungarian tribes, and in 906, the Hungarians conquered it, which some historians attribute to the uncontrolled population growth of Hungarians in the southern parts of the empire without safeguarding the same for the Slavic citizens. The Slavs purportedly hoped that the Hungarians would assimilate into the Slavic state. Czechs and Slovaks were to be disjoined for a thousand years, until 1918, when the federal Czechoslovakia would be established.

Kingdom of Hungary

The Magyars gradually occupied Slovakia, which, nevertheless, retained its privileges in this new state because of its high level of economic and cultural development. For almost two centuries, Slovakia was ruled autonomously as the Principality of Nitra within the Kingdom of Hungary. Slovak settlements extended to the northern half of present-day Hungary, while Hungarians later settled down in the southern part of Slovakia. The ethnic composition became more diverse with the arrival of the Carpathian Germans in the thirteenth century, Vlachs in the fourteenth century, and Jews.

A huge population loss resulted from the invasion of the Mongols in 1241 and the subsequent famine. However, medieval Slovakia was characterized rather by burgeoning towns, construction of numerous stone castles, and the development of arts. In 1467, King Matthias Corvinus established the first university in Bratislava, although the institution was short-lived.

After the Ottoman Empire began expanding into Hungary and invaded Budapest in the early sixteenth century, the center of the Kingdom of Hungary shifted toward Slovakia, and Bratislava (Pressburg, Pressporek, Pozsonium or Pozsony) became the capital in 1536. The Ottoman wars and frequent insurrections against the Habsburg Monarchy inflicted a great deal of destruction, especially in rural areas.

As the Turks retreated from Hungary in the eighteenth century, Slovakia's standing within the kingdom decreased, although Bratislava retained its position of the capital city of Hungary until 1848, when the capital was moved back to Budapest.

National Revival Movement

The first attempt to enact the literary Slovak language (based on the western Slovakian dialect) came in 1787 by Anton Bernolák, but it was not accepted by Slovak Protestants. Only the 1843 version of the language, authored by Štúr, Hurban, and Hodža and based on the central Slovakian dialect, won the support of general public. Lacking a state structure of its own, Slovakia was forced to enlist assistance with the revival cause from similar ideological movements in Hungary. However, Hungary in the 1840s changed course toward a quest for a unified state independent of Austria, which was not to be endorsed by Slovaks, who had been suppressed by Hungarians since the outset of the Kingdom of Hungary.

In May 1848, Requests of the Slovak Nation were drafted calling for the use of the Slovak language in schools and public offices, but neither Hungary nor Austria took them seriously. Nor did the European Revolutions of 1848 bring about a turnaround, as Hungary stepped up repressions of non-Hungarian nationalities, particularly after the forming of the Dual Monarchy, whereby Hungary became independent of Vienna. In the 1870s, Magyars closed down Slovak high schools and the national institute for the promotion of Slovak culture (Matica slovenská) as Magyarization was forced on Slovaks in all aspects of life. This continued until the emergence of Czechoslovakia in 1918. Still, this was an important period in the life of the nation, as it accelerated the breakdown of feudalism and foreshadowed the emergence of an independent Slovak state later on. It was carried out by intelligentsia, mostly of non-aristocratic background, and as such, the movement was thus more democratic by nature.

Czechs, on the other hand, had to deal with Germanization, which ultimately brought the two nations together. This was also fueled by Slovakia's disappointment with Hungarian reformists who were increasingly unwilling to fit the Slovak agenda within their own, and later crystallized into the idea of a joint state of Czechs and Slovaks, promulgated by Milan Rastislav Štefánik, Tomas Garrigue Masaryk, and Eduard Beneš. However, the multi-ethnic makeup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire did not allow for a free pursuit of these goals; therefore, sympathies of the outside world had to be secured—Czechoslovak Legions as well as the Czechoslovak National Council (1916) were formed, and ties were made with European statesmen. In 1915, the Cleveland Agreement laid out an equal position of both countries within the future Czecho-Slovak federal republic.

Twentieth century

Czechoslovak Republic

In 1918, Slovakia joined the regions of Bohemia and neighboring Moravia to form Czechoslovakia. During the chaos following the breakup of Austro-Hungarian Empire, it was attacked in 1919 by the provisional Hungarian Soviet Republic and one-third of its territory temporarily became the Slovak Soviet Republic.

Although the 1920 Constitution of the Czechoslovak Republic guaranteed certain country-specific rights and privileges to Slovakia, they were not fully respected, in contradiction with the Pittsburgh Agreement of 1918 that stipulated autonomous rights for Slovaks, including the right to the Slovak language as the official language of Slovakia. The policy was based on Czechoslovakism, a doctrine that originated during World War I in an effort to create a joint state of Czechs and Slovaks by means of unification, especially of the two languages. A large number of Czechs came to alleviate Slovakia’s shortage of managers and civil servants, although this became a source of controversy during time when the Czechs continued to control the lucrative posts even after the Slovak intelligentsia was brought up. Frustration gave in to an anti-government demonstration staged by Andrej Hlinka, who formed Hlinka’s Slovak People’s Party (HSĽS) as a platform to enforce demands for a separate parliament, administrative bodies, judiciary, and the official language. His party played a major role in the subsequent Slovak State. Nevertheless, historians agree that the existence of Czechoslovakia has benefited Slovakia greatly in that it allowed it to almost close the economic and cultural gap with its western neighbor.

Between World War I and World War II, the existence of the democratic and prosperous Czechoslovakia was jeopardized by revisionist governments of Germany and Hungary, until it was finally split by the Munich Agreement of 1938.

Slovak State

The infamous Munich Treaty of September 1938 resulted in the unification of most political parties around the Party of Slovak National Unity (HSĽS)-sponsored demand for the political autonomy of Slovakia and thus the decentralization of the executive and legislative power of Czechoslovakia. The Prague government of General Jan Syrovy did not oppose these demands, and the acting head of the HSĽS, Jozef Tiso, was appointed as minister for the administration of Slovakia. On November 22, 1938, Slovakia’s political autonomy was signed into law, although part of its territory was taken over by Hungary, and Germany occupied portions of Bratislava. Democratic reforms quickly gave in to an authoritarian rule marked by political censorship and a forceful unification of political parties and social organizations. The HSĽS leadership was gradually overpowered by its radical wing vying for no less than absolute independence of the country, to which the Czechoslovak government responded with intervention and internment of 250 Slovak radicals. To Slovakia, this felt as an attack on its autonomy.

In the meantime, Hitler took advantage of Slovakia's aspirations and invited Tiso to Berlin to coerce him into the secession of Slovakia and thus the liquidation of Czechoslovakia. Should Tiso disagree, Slovakia would be given to Hungary. On March 14, 1939, the Slovak Parliament gave a green light to the Slovak State, with the new government headed by Tiso. However, Czechoslovakia did not cease to exist; it continued its existence via an exiled government and armed forces as well as foreign embassies. At the same time, the independent Slovakia had its hands tied by agreements with Germany and generally had no choice but to align its economy with Hitler's plans, who found it all too easy to control the country headed by the corrupt leadership backed by the Roman Catholic Church. Slovakia even had its own currency, but because Germany did not honor the economic agreements and, paradoxically, incurred a large debt, the Slovak government resorted to anti-Jewish measures to replenish its coffers. In September 1940, the government ordered registration of the Jewish property, which was then confiscated, totaling 3,187,657 Slovak crowns.

Despite plundering by Germany, Slovakia boasted one of the most stable economies among neighboring countries. This was reinforced by the statement used by state officials that Slovakia remains to be an “oasis of affluence amid starving and bleeding Europe.”[6] The tendency was toward centralization, mergers of businesses and their subsequent state control, and nationalization of natural resources. Employment was at its highest, mostly as a consequence of the resettlement of 20,000 Czech civil servants and the elimination of Jews from the economic life and later on their transport to Nazi concentration camps. Education, science, and arts underwent revitalization.

The plight of Slovak Jews under the Slovak state continues to haunt Slovakia’s past, and the anti-Jewish laws of 1940, mandating Aryanization, prove that anti-Semitism ran amok prior to deportations. Jews were prohibited from the acquisition of businesses, were allowed to lease and handle immovables and movables only with a prior written permission, and their trade licenses were revised and businesses marked as Jewish. In the next batch of legislation, the government assigned itself the right to adopt all measures required to exclude Jews from the Slovak economic and social life and transfer Jewish ownership to Christians, and, finally, to deport them, to be paid with the proceeds from the confiscated Jewish property. These laws had an impact on Slovakia’s economy, as many people, especially the executors of the Aryanization laws, pocketed the Jewish wealth and occupied their vacated apartments.

Slovak National Uprising

In 1943, the Slovak state began experiencing severe problems with supply amid rampant corruption and usury. The “Oasis of Affluence” was losing its luster, and even the fact that Germany and other neighboring countries were under greater deprivation could not stem the growing discontent. Politicians with anti-German leanings publicly acknowledged the existence of Czechoslovakia in the Christmas Agreement and proclaimed allegiance to the joint state of Czechs and Slovaks against Hitler’s Germany. Crucial to the agreement was the preparation of an armed conflict and removal of the HSĽS from power.

Pro-democratic citizens began participating in the resistance movement, and two-thirds of the Slovak currency was made available to the cause. Weaponry, which at one time came in handy to the fascist Germany, was transferred surreptitiously to the designated centers of the uprising. In August 1944, the U.S. Air Force bombed a state-owned refinery in Central Slovakia despite multiple warnings sent to the exiled Czechoslovak government in London that the refinery was crucial to the uprising-in-the-works.

The Slovak National Uprising broke out on August 29, 1944, and a few days later the joint state of Czechs and Slovaks was to be restored as a federal structure. Black market practices and corruption that had been tolerated by the government and paramilitary Hlinka's Guard (Hlinkova Garda) were being reversed. The final stage of the uprising was in the spirit of partisan activities rather than open resistance.

After World War II

After World War II, Slovakia became part of Czechoslovakia as a satellite of the communist Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact. In 1968, Czechoslovakia courted liberation from the communist grip in the events referred to as the Prague Spring, when it made an attempt to reform the regime from within and embark on the path toward liberalization and a multi-party system. Slovak-born Alexander Dubcek became a symbol of these developments. However, the Warsaw Pact armies invaded and crushed Czechoslovakia's hopes under the tanks as the Western world watched. In 1969, Czechoslovakia was reorganized as a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic.

The end of the infamous 40 years finally came in 1989, during the peaceful Velvet Revolution. Four years later, on January 1, 1993, the country was dissolved once again into two successor states. Slovakia and the Czech Republic went their own ways after the Velvet Divorce but have remained close partners. Slovakia joined the European Union in May 2004.

Geography

Located at the heart of Europe, Slovakia shares borders with Poland to the north, the Czech Republic in the northwest, Austria in the southwest, Hungary to the south, and the Ukraine to the east. It is a mountainous country with almost 80 percent of its total area above 2,460 feet (750 meters). It encompasses 48,845 square kilometers; 48,800 being land and the remaining 45 square kilometers of water. This makes it approximately twice the size of the U.S. state of New Hampshire.

The Slovak landscape is crowned by the Carpathian Mountains extending across most of the northern half of the country. The most notable range is the Tatras, home to scenic lakes and valleys as well as the highest peak, the Gerlachovský štít (2,655 meters/8,711 feet). South of the Low Tatras the land drops to a fertile plain stretching to the Danube River.

Forests, especially of beech and spruce, cover 40 percent of the country. Wildlife is abundant in the valleys of the High Tatra and includes bears, wolves, lynxes, marmots, chamois, deer, mink]] and otter. Birdlife includes eagles, hawks, vultures, pheasants, partridges, ducks, wild geese, storks, and grouse.

The Danube, Váh, and Hron are the largest rivers. The climate is temperate, with relatively warm summers and cold, cloudy and humid winters.

Demographics

Slovaks form the majority of the population, with Hungarians being the largest ethnic minority, concentrated in the southern and eastern regions of the country. Several municipalities, such as Dunajská Streda, Komárno, Šahy, and Želiezovce, are majority Hungarian. Other ethnic groups include Roma, Czechs, Ruthenians, Ukrainians and Germans.

The majority of Slovaks identify themselves with Roman Catholicism, followed by Lutheranism and Greek Catholicism. Only around 2,000 Jews remain of the 120,000-strong pre-Holocaust population.

The official language is Slovak, a member of the Slavic language family, but Hungarian is widely spoken in the south and enjoys the same status as does Slovak language in some regions.

Society and culture

The development of Slovak culture reflects the country’s rich folk tradition, in addition to the influence of broader European trends. The impact of centuries of cultural repression and control by foreign governments is also evident in much of Slovakia’s art, literature, and music.

A national movement began in the late eighteenth century aimed at fostering Slovak culture and identity. One of its leaders was Anton Bernolk, a Jesuit priest who codified a Slovak literary language based on dialects used in western Slovakia. In the nineteenth century, Protestant leaders Jan Kollar and Pavel Safarik developed a form of written Slovak that combined the dialects used in central Slovakia and the Czech lands.

Poetry remained an important literary form into the twentieth century, and was used by some Slovak writers to address the experience of World War II and the rise of communism. During the communist period, Slovak literary culture suffered from heavy governmental control.

An important aspect of cultural life in Slovakia is its music. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a national musical tradition began to develop around Slovakia’s impressive folk heritage. Modern Slovak music draws from both classical and folk styles. Traditional Slovakian music is one of the most original of Slavic and European folklore. National Slovakian music was heavily influenced by liturgical and chamber music.

Politics

Slovakia is a parliamentary democratic republic with a multi-party system. The head of state is the president, elected in a direct popular vote for a five-year term. Executive power is concentrated in the hands of the prime minister, who is most frequently the leader of the winning party and has to form a majority coalition in the parliament. The prime minister is appointed by the president. The remainder of the cabinet is appointed by the president on the recommendation of the prime minister.

The highest legislative body is the 150-seat unicameral National Council of the Slovak Republic (Národná rada Slovenskej republiky). Delegates are elected for a four-year term on the basis of a proportional representation. The Constitutional Court (Ústavný súd) is the highest judicial body; its 13 members are appointed by the president.

Slovakia joined the European Union on May 1, 2004, and NATO on March 29, 2004. As a member of the United Nations since 1993, it was elected for the first time to a two-year term on the United Nations Security Council on October 10, 2005.

Administrative divisions

Slovakia is subdivided into eight regions/countries (kraje) named after their respective principal cities. The regions enjoy a degree of autonomy.

- Bratislava Region (Bratislavský kraj) (capital Bratislava)

- Trnava Region (Trnavský kraj) (capital Trnava)

- Trenčín Region (Trenčiansky kraj) (capital Trenčín)

- Nitra Region (Nitriansky kraj) (capital Nitra)

- Žilina Region (Žilinský kraj) (capital Žilina)

- Banská Bystrica Region (Banskobystrický kraj) (capital Banská Bystrica)

- Prešov Region (Prešovský kraj) (capital Prešov)

- Košice Region (Košický kraj) (capital Košice)

(the word kraj can be replaced by samosprávny kraj or by VÚC in each case)

The regions are further subdivided into 79 districts (okresy).

In terms of economy and unemployment rate, the western regions fare better than the eastern regions.

Economy

Slovakia has transitioned from the centrally planned economy to a modern market economy. Major privatizations are completed, the banking sector is almost completely in private hands, and foreign investment has risen. It now has a developed, high-income economy, although the country has difficulties addressing regional imbalances in wealth and employment. The country adopted the Euro currency in 2009.

The Slovak government encourages foreign investment, since it is one of the driving forces of the economy. Slovakia is an attractive country for foreign investors mainly because of its low wages, low tax rates, well educated labor force, favorable geographic location in the heart of Central Europe, strong political stability, and good international relations reinforced by the country's accession to the European Union. Some regions, mostly at the east of Slovakia have failed to attract major investment, which has aggravated regional disparities in many economic and social areas.

Notes

- ↑ Tab. 10 Obyvateľstvo SR podľa národnosti – sčítanie 2011, 2001, 1991. Portal.statistics.sk. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ↑ CIA, Slovakia The World Factbook.

- ↑ Slovakia Population 2019 World Population Review. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019 International Monetary Fund. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ↑ Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey Eurostat. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ↑ Dušan Mihálik, "Slovenský štát – ekonomický zázrak?" Prave Spektrum Magazine, February 26, 2007. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Axworthy, Mark. Axis Slovakia: Hitler's Slavic Wedge, 1938-1945. Bayside, NY: Axis Europa Books, 2002. ISBN 1891227416

- Bartl, Július. Slovak History: Chronology and Lexicon. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0865164444

- Downs, Jim, World War II: OSS Tragedy in Slovakia. Oceanside, CA: Liefrinck, 2002. ISBN 0971748209

- Drobná, Ol̕ga, Eduard Drobný and Magdalena Gocnikova. Slovakia: The Heart of Europe. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0865163197

- Goldman, Minton F. Slovakia Since Independence: A Struggle for Democracy. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1999. ISBN 0275961893

- Horn, Alfred. Czech & Slovak Republics. Hong Kong: APA Publications; Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993. ISBN 0395659876

- Humphreys, Rob, and Slawomir Adamczak. The Rough Guide to the Czech and Slovak Republics. New York: Rough Guides, 2006. ISBN 1843535254

- Jacobs, Michael. Czech & Slovak Republics. London: A & C Black, 1999. ISBN 071364429X

- Junas, Lil. My Slovakia: An American's View. Matice Slovenskej, 2001. ISBN 8070906227

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. New York, St. Martin's Press, 1995. ISBN 0312104030

- Lazišt̕an, Eugen, Fedor Mikovič, and Ivan Kučma. Slovakia: A Photographic Odyssey. Wauconda, IL, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2001. ISBN 0865165173

- Schuster, Rudolf, and M. Mark Stolarik. The Slovak Republic: A Decade of Independence, 1993-2002. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2003. ISBN 0865165688

- Wilson, Neil, and Richard Nebeský. Czech & Slovak Republics. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet, 2001. ISBN 1864502126

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2023.

- National Council of the Slovak Republic

- Slovak Presidential Office

- Slovakia.org: Guide to the Slovak Republic

- Discover Slovakia

- Slovakia Visa Application Requirements

- Slovakia Travel Guide

Albania · Andorra · Armenia2 · Austria · Azerbaijan1 · Belarus · Belgium · Bosnia and Herzegovina · Bulgaria · Croatia · Cyprus2 · Czech Republic · Denmark3 · Estonia · Finland · France3 · Georgia1 · Germany · Greece · Hungary · Iceland · Ireland · Italy · Kazakhstan1 · Latvia · Liechtenstein · Lithuania · Luxembourg · Republic of Macedonia · Malta · Moldova · Monaco · Montenegro · Netherlands3 · Norway3 · Poland · Portugal · Romania · Russia1 · San Marino · Serbia · Slovakia · Slovenia · Spain3 · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey1 · Ukraine · United Kingdom3 · Vatican City

1 Has majority of its territory in Asia. 2 Entirely in Asia but having socio-political connections with Europe. 3 Has dependencies or similar territories outside Europe.

| North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) | |

|---|---|

| Belgium | Bulgaria | Canada | Czech Republic | Denmark | Estonia | France | Germany | Greece | Hungary | Iceland | Italy | Latvia | Lithuania | Luxembourg | The Netherlands | Norway | Poland | Portugal | Romania | Slovakia | Slovenia | Spain | Turkey | United Kingdom | United States of America | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.