Saint Dominic

- For other saints named Dominic, see the disambiguation page for Dominic

| Saint Dominic | |

|---|---|

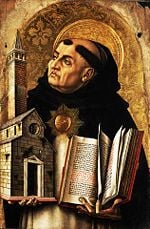

Oldest image of Saint Dominic by an unknown 14th century artist Priory of the Basilica of San Domenico in Bologna, Italy | |

| Confessor | |

| Born | 1170 in Calaruega, Province of Burgos, Kingdom of Castile (now modern-day Castile-Leon, Spain) |

| Died | August 6, 1221 in Bologna, Province of Bologna, Emilia-Romagna, Italy |

| Canonized | 1234 |

| Major shrine | San Domenico, Bologna |

| Feast | August 8 August 4 (Traditional Roman Catholics) |

| Attributes | Confessor; Chaplet, dog, star |

| Patronage | Astronomers; astronomy; Dominican Republic; falsely accused people; Santo Domingo Indian Pueblo; scientists |

Saint Dominic (Spanish: Domingo), also known as Dominic of Osma, often called Dominic de Guzmán and Domingo de Guzmán Garcés (1170 – August 6, 1221) was the founder of the Friars Preachers, popularly called the Dominicans or Order of Preachers (OP), a Catholic religious order. Dominic is the patron saint of astronomers and the Dominican Republic.

Life of St. Dominic

Birth and Parentage

Dominic was born in Caleruega, half-way between Osma and Aranda in Old Castile, Spain. He was named after Saint Dominic of Silos, the patron saint of hopeful mothers and the Benedictine Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos, a few miles north of Caleruega.

In the earliest narrative source, by Jordan of Saxony, Dominic's parents are not named. The story is told that before his birth his mother dreamed that a dog leapt from her womb carrying a torch in its mouth, and "seemed to set the earth on fire." This reference, however is likely to be a later interpolation, as the Latin name of his order, Dominicanus is a pun on "Domini Canus," the "Lord's Hound." (Jordan adds that Dominic was brought up by his parents and a maternal uncle who was an archbishop.[1] The failure to name them is not surprising, since Jordan's work is a history of the early years of the Order rather than a biography of Dominic. A later source, still of the 13th century, gives the names of Dominic's mother and father as Juana de Aza and Felix.[2] Nearly a century after Dominic's birth, a local author asserts that Dominic's father was "vir venerabilis et dives in populo suo" ("an honoured and wealthy man in his village").[3] The earliest statement that Dominic's father belonged to the family de Guzmán, and that his mother belonged to the Aça or Aza family, occurs in the travel narrative of Pero Tafur, written in 1439 or soon after.[4]

Education and early career

Dominic was educated in the schools of Palencia, afterwards a university, where he devoted six years to the arts and four to theology. In 1191, when Spain was desolated by a terrible famine, Dominic was just finishing his theological studies. He gave away his money and sold his clothes, his furniture and even his precious manuscripts, that he might relieve distress. When his companions expressed astonishment that he should sell his books, Dominic replied: "Would you have me study off these dead skins, when men are dying of hunger?" This utterance belongs to the few of Dominic's sayings that have passed to posterity. In 1194, around twenty-five years old, Dominic became a Praemonstratensian canon,[5] in the canonry of Osma, following the rule of Saint Augustine.

In 1203 or 1204 he accompanied Diego de Acebo, the Bishop of Osma, on a diplomatic mission for Alfonso VIII, King of Castile, in order to secure a bride in Denmark for crown prince Ferdinand.[6] The mission made its way to Denmark via the south of France.

When they crossed the Pyrenees, Dominic and Diego encountered the Cathars. They found themselves in an atmosphere of heresy. The country was filled with preachers of strange doctrines, who had become alienated from the Church and had little respect for Dominic, his bishop, or their Roman pontiff. The shocking experiences of this journey inspired in Dominic a desire to aid in the extermination of heresy. He was also deeply impressed by an important and significant observation. Many of these heretical preachers were not ignorant fanatics, but well-trained and cultured men. Entire communities seemed to be possessed by a desire for knowledge and for righteousness. Dominic clearly perceived that only preachers of a high order, capable of advancing reasonable argument, could overthrow the Cathar heresy just as he preached against the Albigensian heresy; and in fact the Inquisition was founded to combat the Albigensian heresy, and many of the early inquisitors were Dominicans. The 14th century Dominican Inquisitor Bernard Gui was also the most influential chronicler of Dominican history: he gave to many stories their definitive form. It seems likely he did not object to a vision in which Dominic figured as an exemplary inquisitor.

Travelling up again to Denmark in 1204 or 1205 and finding that the intended bride had died, Diego and Dominic returned by way of Rome and Citeaux. Dominic then stayed a number of years in the south of France working among the Cathars. In late 1206 or early 1207, with the help of bishop Foulques of Toulouse, and thanks to the generosity of Guillaume and Raymonde Claret, Diego and Dominic were able to set up a first monastic community at Prouille near Carcassonne, intended largely as a refuge for women who had previously lived in Cathar religious houses. Soon afterwards Diego, at the pope's insistence, returned to his diocese. Still in 1207, Dominic took part in the last large scale public debate between Cathars and Catholics, at Pamiers.

Foundation of the Dominicans

In 1208 Dominic encountered the papal legates returning in pomp to Rome, foiled in their attempt to crush the growing sect. To them he administered his famous rebuke: "It is not by the display of power and pomp, cavalcades of retainers, and richly-houseled palfreys, or by gorgeous apparel, that the heretics win proselytes; it is by zealous preaching, by apostolic humility, by austerity, by seeming, it is true, but by seeming holiness. Zeal must be met by zeal, humility by humility, false sanctity by real sanctity, preaching falsehood by preaching truth."

A small group of priests formed around Dominic, but soon left him since the challenge and rigours of a simple lifestyle together with demanding preaching discouraged them. Finally Dominic gathered a number of men who remained faithful to the vision of active witness to the Albigensians as well as a way of preaching which combined intellectual rigour with a popular and approachable style. By departing from accepted church practices and learning from the Albigensians, Dominic laid the ground for what would become a major tenet of the Dominican order over time - to find truth no matter where it may be.

In 1215, Dominic established himself, with six followers, in a house given by Pierre Seila, a rich resident of Toulouse. He subjected himself and his companions to the monastic rules of prayer and penance; and meanwhile bishop Foulques gave them written authority to preach throughout the territory of Toulouse. Thus the scheme of establishing an order of Preaching Friars began to assume definite shape in Dominic's mind. He dreamed of seven stars enlightening the world, which represented himself and his six friends.

The final result of his deliberations was the establishment of his order. In the same year, the year of the Fourth Lateran Council, Dominic and Foulques went to Rome to secure the approval of the Pope, Innocent III. Dominic returned to Rome a year later, and was finally granted written authority in December 1216 and January 1217 by the new pope, Honorius III for an order to be named "The Order of Preachers" ("Ordo Praedicatorum", or "O.P.," popularly known as the Dominican Order).[7] This organization has as its motto "to praise, to bless, to preach" (Latin: Laudare, benedicere, praedicare), taken from the Preface of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Roman Missal.

Dominic's Later life

Dominic now made his headquarters at Rome, although he traveled extensively to maintain contact with his growing brotherhood of monks. It was in the winter of 1216–1217, at the house of Ugolino de' Conti, that he first met William of Montferrat, afterwards a close friend.

When arriving in Bologna in January 1218, he saw immediately that this university city was most convenient as his center of activity. Soon a convent was established at the Mascarella church by the Blessed Reginald of Orléans. Soon afterwards they had to move to the church of San Nicolò of the Vineyards. Dominic settled in this church and held in this church the first two General Chapters of the order. He died there on 6 August 1221 and was moved into a simple sarcophagus in 1233.

The church was later expanded and grew into the Basilica of Saint Dominic, consecrated by Pope Innocent IV in 1251. In 1267 Dominic's remains were moved to the exquisite shrine, made by Nicola Pisano and his workshop, Arnolfo di Cambio and with later additions by Niccolò dell'Arca and the young Michelangelo. At the back of this shrine, the head of Dominic is enshrined in a huge, golden reliquary, a masterpiece of the goldsmith Jacopo Roseto da Bologna (1383).

Throughout his life, Dominic is said to have zealously practiced rigorous self-denial. He wore a hairshirt, and an iron chain around his loins, which he never laid aside, even in sleep. He abstained from meat and observed stated fasts and periods of silence. He selected the worst accommodations and the meanest clothes, and never allowed himself the luxury of a bed. When traveling, he beguiled the journey with spiritual instruction and prayers. As soon as he passed the limits of towns and villages, he took off his shoes, and, however sharp the stones or thorns, he trudged on his way barefooted. Rain and other discomforts elicited from his lips nothing but praises to God.

Death came at the age of fifty-one and found him exhausted with the austerities and labors of his eventful career. He had reached the convent of St Nicholas at Bologna, Italy, weary and sick with a fever. He refused the repose of a bed and made the monks lay him on some sacking stretched upon the ground. The brief time that remained to him was spent in exhorting his followers to have charity, to guard their humility, and to make their treasure out of poverty. He died at noon on 6 August 1221.

Inquisition

What part Dominic personally had in the proceedings of the episcopal Medieval Inquisition has been disputed for many centuries. The historical sources from Dominic's own time period tell us nothing about his involvement in the Inquisition. This is all the more striking when we consider that several early Dominicans, including some of Dominic's first followers, did become inquisitors. In fact, the notion that Dominic had been an inquisitor only began in the 14th century through the writings of a famous Dominican inquisitor, Bernard Gui, who tried to paint his Order's founder as a participant in the Institution. One of the most difficult aspects of Catholic history has been the denial of Church that Dominic not only was a part of the Inquisition, but took an active part in it.

The Colloquy of Montréal in 1207 was the final debate in Pamiers between the Catholics (represented by Dominic Guzmán) and the Cathars (notably Benoît de Termes). Once again the the Roman Church made no progress, and if anything confirmed its role as a figure of fun and reservoir of ignorance and bigotry. When a great noblewoman, the Esclarmonde of Foix (the Count's sister), a Parfaite, tried to speak she was admonished by one of Dominic Guzmán's acolytes (Etienne de Metz): "go to your spinning madam. It is not proper for you to speak in a debate of this sort". Such attitudes voiced in front of a liberal educated audience succeeded only in confirming the extent of the gulf between the Roman Church and the general population of the Languedoc. In any case, even with God's personal help, the Roman Church once again failed to secure mass conversions, or indeed any conversions at all among the Parfaits.

Guzmán was humiliated by his failure. More vigorous action was called for. The great Bernard of Clairvaux (St Bernard) had asserted that "The Christian glories in the death of a pagan, because Christ is thereby glorified". Were not heretics even worse than pagans, even more deserving of death. Speaking on behalf of Christ, Guzmán promised the Cathars slavery and death .

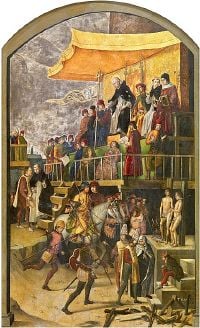

In the 15th century, Dominic would be depicted as presiding at an auto da fé, later offering German Protestant critics of the Catholic Church a convenient publicity weapon against the very Order whose theologically informed preaching had proven to be a formidable opponent in the lands of the Reformation. Thus a 14th century invention soon became a part of the Black Legend.

Rosary

Some histories of the Rosary claim its origin to Saint Dominic through the Blessed Virgin Mary[9]. Our Lady of the Rosary is the title received by the Marian apparition to Saint Dominic in 1208 in the church of Prouille in which the Virgin Mary gave the Rosary to him. However, other sources dispute this attribution and suggest that its roots were in the preaching of Alan de Rupe between 1470-1475, and suggest that Saint Dominic had nothing to do with the Rosary[10]. There are sources trying to seek a middle ground to these two views[11]. Either way, the Rosary has for centuries been at the heart of the Dominican Order. Pope Pius XI stated that: "The Rosary of Mary is the principle and foundation on which the very Order of Saint Dominic rests for making perfect the life of its members and obtaining the salvation of others." [12]

For centuries, Dominicans have been instrumental in spreading the rosary and emphasizing the Catholic belief in the power of the rosary[13].

Patrick Cardinal Hayes of New York provided his imprimatur in support of the fifteen rosary promises attributed to Saint Dominic and Alan de Rupe[14]. In this attribution, based on some Catholic beliefs on the power of prayer the Blessed Virgin Mary reportedly made fifteen specific promises regarding the power of the rosary to Christians who pray the rosary [15]. The fifteen rosary promises range from heavenly protection from misfortune to assurance of sanctification, and to meriting a high degree of glory in heaven [16].

See also

- Santo Domingo

- Vardapet; traveling preachers of the Armenian Church

- Pattern of Urlaur

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Jordan of Saxony, "Libellus de principiis, 4." The dream has been thought to allude to the medieval pun on the name of the Dominicans, Domini canes, "dogs of the Lord"; it has also been argued that the dream suggested the pun.

- ↑ Pedro Ferrando, "Legenda Sancti Dominici, 4." Juana is customarily rendered "Jane" in English.

- ↑ Rodrigo de Cerrato, "Vita S. Dominici"

- ↑ Pero Tafur, Andanças e viajes (tr. Malcolm Letts, p. 31), describing a pilgrimage to Dominic's burial place. Tafur's book is dedicated to a member of the Guzmán family.

- ↑ Canons Regular of Premontre: Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ Jordan of Saxony, "Libellus de principiis" p. 14-20; Gérard de Frachet, "Chronica prima" [MOPH 1.321].

- ↑ See "Religiosam vitam"; "Nos attendentes"

- ↑ *Page of the painting at Prado Museum.

- ↑ Catherine Beebe, St. Dominic and the Rosary ISBN 0898705185

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13184b.htm

- ↑ History of the Rosary http://www.ewtn.com/library/ANSWERS/ROSARYHS.htm

- ↑ Robert Feeney. St. Dominic and the Rosary. Catholic.net. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ History of the Dominicans http://www.domcentral.org/study/ashley/ds02ital2.htm

- ↑ Rosary promises http://www.catholic.org/clife/mary/promises.php

- ↑ Dominican Fathers on the Rosary http://www.rosary-center.org/nconobl.htm

- ↑ Holyrosary.org http://www.theholyrosary.org/power.html

Bibliography

- Alfred Wesley Wishart. A Short History of Monks and Monasteries. 1900. Project Gutenberg etext

- Guy Bedouelle, "The Holy Inquisition: Dominic and the Dominicans," an article on the main Dominican website

- Catholic Encyclopedia: St. Dominic by John B. O'Conner, 1909.

- Simon Tugwell, "Early Dominicans," New York: Paulist Press, 1982.

- M.-H. Vicaire, "Saint Dominic and his Times," transl. by Kathleen Pond, Green Bay, Wisconsin, Alt Publishing, 1964.

- McGonigle, Thomas and Phyllis Zagano "The Dominican Tradition" (Spirituality in History Series) (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press) 2006.

External links

- ORDO PRAEDICATORUM (OP) - The homepage of Dominicans (Black Friars).

- The website of Czech Dominicans.

- Bishop Foulques's authorization of 1215 (French translation)

- Founder Statue in St Peter's Basilica

- Lectures in Dominican History

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.