Difference between revisions of "Marsupial mole" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Marsupial mole''' is the common name for any of the [[marsupial]] [[mammal]]s belonging to the family '''Notoryctidae''' of the order '''Notoryctemorphia''', as well as for members of the order Notoryctemorphia itself. There are two extant species in this family and order, ''Notoryctes typholops'' (southern marsupial mole) and ''Notoryctes caurinus'' (northern marsupial mole). The extant species are characterized by a tubular body shape, short silky [[fur]], short and stout tails, snouts covered by a horny shield, forefeet with enlarged third and fourth digits with enormous claws, a pouch that opens to the exterior, and fossorial (burrowing) behavior. These small mammals (about 6 to 7 inches in body length) are found in Western [[Australia]]. | + | '''Marsupial mole''' is the common name for any of the [[marsupial]] [[mammal]]s belonging to the family '''Notoryctidae''' of the order '''Notoryctemorphia''', as well as for members of the order Notoryctemorphia itself. There are two extant species in this family and order, ''Notoryctes typholops'' (southern marsupial mole) and ''Notoryctes caurinus'' (northern marsupial mole). The extant species are characterized by a tubular body shape, short silky [[fur]], short and stout tails, functionally blind eyes, snouts covered by a horny shield, forefeet with enlarged third and fourth digits with enormous claws, a pouch that opens to the exterior, and fossorial (burrowing) behavior. These small mammals (about 6 to 7 inches in body length) are found in Western [[Australia]]. |

| + | |||

| + | feed on ant pupae, beetles, beetle and moth larvae, sawfly larvae | ||

==Overview and description== | ==Overview and description== | ||

| + | Marsupial moles are rare and poorly understood burrowing [[mammal]]s of the [[desert]]s of [[Western Australia]]. The most fossorial of all the marsupials, they also are the only Australian mammals specialized for a burrowing lifestyle (ZSL 2014). They spend the majority of time tunneling below the ground's surface, pushing through with their horny noses, but with the tunnels collapsing behind them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Zoological Society of London (ZSL). 2014. [http://www.edgeofexistence.org/mammals/species_info.php?id=31 Marsupial mole, southern marsupial mole (''Notoryctes typhlops'')]. ''Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) website''. Retrieved March 5, 2014. | ||

| − | + | , with an ancestry going back 20 million years or so. Once classified as a [[monotreme]], they are now known to be a [[marsupial]]. Their precise classification was for long a matter for argument, but there are considered to be only two extant species:<ref name=msw3/> | |

* ''[[Notoryctes typhlops]]'' (southern marsupial mole, known as the ''itjaritjari'' by the [[Pitjantjatjara people|Pitjantjatjara]] and [[Yankunytjatjara]] people in Central Australia).<ref>{{cite web | accessdate = 2006-11-09 | title = Mole Patrol | year = 2004 | work = The Marsupial Society | url = http://www.marsupialsociety.org/members/mole_patrol.html}}</ref> | * ''[[Notoryctes typhlops]]'' (southern marsupial mole, known as the ''itjaritjari'' by the [[Pitjantjatjara people|Pitjantjatjara]] and [[Yankunytjatjara]] people in Central Australia).<ref>{{cite web | accessdate = 2006-11-09 | title = Mole Patrol | year = 2004 | work = The Marsupial Society | url = http://www.marsupialsociety.org/members/mole_patrol.html}}</ref> | ||

* ''[[Notoryctes caurinus]]'' (northern marsupial mole, also known as the ''kakarratul'') | * ''[[Notoryctes caurinus]]'' (northern marsupial mole, also known as the ''kakarratul'') | ||

Revision as of 23:42, 5 March 2014

| Marsupial moles[1]

| ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

Marsupial mole is the common name for any of the marsupial mammals belonging to the family Notoryctidae of the order Notoryctemorphia, as well as for members of the order Notoryctemorphia itself. There are two extant species in this family and order, Notoryctes typholops (southern marsupial mole) and Notoryctes caurinus (northern marsupial mole). The extant species are characterized by a tubular body shape, short silky fur, short and stout tails, functionally blind eyes, snouts covered by a horny shield, forefeet with enlarged third and fourth digits with enormous claws, a pouch that opens to the exterior, and fossorial (burrowing) behavior. These small mammals (about 6 to 7 inches in body length) are found in Western Australia.

feed on ant pupae, beetles, beetle and moth larvae, sawfly larvae

Overview and description

Marsupial moles are rare and poorly understood burrowing mammals of the deserts of Western Australia. The most fossorial of all the marsupials, they also are the only Australian mammals specialized for a burrowing lifestyle (ZSL 2014). They spend the majority of time tunneling below the ground's surface, pushing through with their horny noses, but with the tunnels collapsing behind them.

- Zoological Society of London (ZSL). 2014. Marsupial mole, southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops). Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) website. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

, with an ancestry going back 20 million years or so. Once classified as a monotreme, they are now known to be a marsupial. Their precise classification was for long a matter for argument, but there are considered to be only two extant species:[1]

- Notoryctes typhlops (southern marsupial mole, known as the itjaritjari by the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people in Central Australia).[2]

- Notoryctes caurinus (northern marsupial mole, also known as the kakarratul)

The two species of marsupial moles are so similar to one another that they cannot be reliably told apart in the field.

Marsupial moles spend most of their time underground, coming to the surface only occasionally, probably mostly after rains. They are blind, their eyes having become reduced to vestigial lenses under the skin, and they have no external ears, just a pair of tiny holes hidden under thick hair. They do not dig permanent burrows, but fill their tunnels in behind them as they move.

The head is cone-shaped, with a leathery shield over the muzzle, the body is tubular, and the tail is a short, bald stub. They are between 12 and 16 cm long, weigh 40 to 60 grams, and are uniformly covered in fairly short, very fine pale cream to white hair with an iridescent golden sheen. Their pouch has evolved to face backwards so it does not fill with sand, and contains just two teats, so the animal cannot bear more than two young at a time.

The limbs are very short, with reduced digits. The forefeet have two large, flat claws on the third and fourth digits, which are used to excavate soil in front of the animal. The hindfeet are flattened, and bear three small claws; these feet are used to push soil behind the animal as it digs. In a feature unique to this animal, the neck vertebrae are fused to give the head greater rigidity during digging.[3]

Marsupial moles provide a remarkable example of convergent evolution, with moles generally, and with the golden moles of Africa in particular. Although only related to other moles in that they are all mammals, the external similarity is an extraordinary reflection of the similar evolutionary paths they have followed.

They are insectivorous, feeding primarily on beetle larvae and cossid caterpillars.[3] Their teeth have a somewhat simplified structure, but their dental formula is similar to that of other marsupials:

| Dentition |

|---|

| 4.1.2.4 |

| 3.1.3.4 |

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Although the Notoryctidae family is poorly represented in the fossil record there is evidence of at least one distinct genus Yalkaparidon, in the early Miocene sediments in the Riversleigh deposit in northern Australia.[4]

- For many years, their place within the Marsupialia was hotly debated, some workers regarding them as an offshoot of the Diprotodontia (the order to which most living marsupials belong), others noting similarities to a variety of other creatures, and making suggestions that, in hindsight, appear bizarre. A 1989 review of the early literature,[citation needed] slightly paraphrased, states:

- When Stirling (1888) initially was unable to find the epipubic bones in marsupial moles, speculation was rife: the marsupial mole was a monotreme, it was the link between monotremes and marsupials, it had its closest affinities with the (placental) golden moles, it was convergent with edentates, it was a polyprotodont diprotodont, and so on.

- The mystery was not helped by their complete absence in the fossil record. On the basis that marsupial moles have some characteristics in common with almost all other marsupials, they were eventually classified as an entirely separate order: the Notoryctemorphia. Molecular level analysis in the early 1980s showed the marsupial moles are not closely related to any of the living marsupials, and they appear to have followed a separate line of development for a very long time, at least 50 million years. However, some morphological evidence suggests they may be related to bandicoots.

Due to their highly specialized morphology and the fact that notoryctids share many common characteristics with other marsupials, there has been much debate surrounding their phylogeny. However, recent molecular studies indicate that notoryctids are not closely related to any of the other marsupial families and should be placed in an order of their own, Notoryctemorphia.[5][6]

Furthermore, molecular data suggests that Notoryctemorphia separated from other marsupials around 64 million years ago.[7] Although at this time South America, Antarctica and Australia were still joined the order evolved in Australia for at least 40-50 million. The Riversleigh fossil material suggests that Notoryctes was already well adapted for burrowing and probably lived in the rainforest that covered much of Australia at that time. The increase in aridity at the end of Tertiary was likely one of the key contributing factors to the development of the current highly specialized form of marsupial mole.[8] The marsupial mole had been burrowing long before the Australian deserts came into being.[9]

- In 1985, the vast, newly discovered limestone fossil deposits at Riversleigh in northern Queensland yielded a major surprise: a fossil between 15 and 20 million years old named Yalkaparidon coheni with molars like a marsupial mole, diprotodont-like incisors, and a skull base similar to that of the bandicoots. These features were by no means identical to the living species, but clearly related, and possibly even of a direct ancestor. In itself, the discovery of a Miocene marsupial mole (Naraboryctes philcreaseri) presented no great mysteries. Just like the modern forms, it had many of the features that are assumed to be adaptations for a life burrowing in desert sands, in particular the powerful, spade-like forelimbs. The Riversleigh fossil deposits, however, are from an environment that was not remotely desert-like: in the Miocene, the Riversleigh area was a tropical rainforest.

- One suggestion advanced was that the Miocene marsupial mole used its limbs for swimming rather than burrowing, but the mainstream view is that it probably specialised in burrowing through a thick layer of moss, roots, and fallen leaf litter on the rainforest floor, and thus, when the continent began its long, slow desertification, the marsupial moles were already equipped with the basic tools that they now use to burrow in the sand dunes of the Western Australian desert.

Southern marsupial mole

}}

The Southern Marsupial Mole (Notoryctes typhlops) is a mole-like marsupial found in the desert of southwest Australia. It is extremely adapted to a burrowing way of life. It has large, shovel-like forepaws and silky fur, which helps it move easily. The Southern Marsupial Mole also lacks complete eyes as it has little need for them. It feeds on earthworms and larvae.[10]

History of discovery

Although the Southern Marsupial Mole was probably known by aborigines for thousands of years, the first specimen examined by the scientific community was collected in 1888. Stockman W. Coulthard made the discovery on Idracowra Pastoral Lease in the Northern Territory by following some unusual prints that lead him to the animal lying under a tussock.[8] Not knowing what to do with the strange creature, he wrapped it in a kerosene soaked rag, placed it in a revolver cartridge box and forwarded it to E.C. Stirling, the Director of the South Australian Museum. Due to the poor transportation conditions of the time, the specimen reached its destination in a badly decomposed state. Hence, Stirling was unable to find any evidence of the pouch or epipubic bones and decided the creature was not a marsupial.[11]

19th century scientists believed that marsupials and eutherians had evolved from the same primitive ancestor and were looking for a living specimen that would act as the missing link. Because the marsupial mole closely resembled the golden moles of Africa, some scientists concluded that the two were related and that they had found the proof. This is of course not the case, as it became obvious by examining better preserved specimens that had a marsupial pouch.[11]

Morphology

The Southern Marsupial Mole is small in size, with a head and body length varying from 121 to 159 mm, a tail length of 21–26 mm and a weight of 40-70 g. The body is covered with short, dense, silky fur with a pale cream to white color often tinted by the iron oxides from the soil which gives it a reddish chestnut brown tint. It has a light brownish pink nose and mouth and no vibrissae.[12]

The cone shaped head merges directly with the body, and there is no obvious neck region. The limbs are short and powerful, and digits III and IV of the manus have large spade-like claws. The dentition varies with individuals and, because the molars have a root of only one third of the length, it has been assumed that moles cannot deal with hard food substances.[8] The dorsal surface of the rostrum and the back of the tail have no fur and the skin is heavily keratinized. There is no external evidence of the eyes, and the optic nerve is absent. It does have however a pigment layer where the eyes should be, probably a vestige of the retina. Both lachrymal glands and Jacobson's organ are well developed, and it has been suggested that the former plays a role in lubricating the nasal passages and Jacobson's organ.

The external ear openings are covered with fur and do not have a pinnae. The nostrils are small vertical slits right below the shield-like rostrum. Although the brain has been regarded as very primitive and represents the "lowliest marsupial brain", the olfactory bulbs and the rubercula olfactoria are very well developed. This seems to suggest that the olfactory sense plays an important role in the marsupial moles' life, as it would be expected for a creature living in an environment lacking visual stimuli. The middle ear seems to be adapted for the reception of low-frequency sounds.[12]

Adaptations

The Southern Marsupial Mole resembles the Namib Desert Golden Mole and other specialized fossorial animals in having a low and unstable body temperature, ranging between 15-30°C. It does not have an unusually low resting metabolic rate, and the metabolic rate of burrowing is 60 times higher than that of walking or running. Because it lives underground, where the temperature is considerably lower than at the surface, the Southern Marsupial Mole does not seem to have any special adaptations to desert life. It is not known whether it drinks water or not, but due to the infrequence of rain it is assumed that it does not.[9]

Habitat and distribution

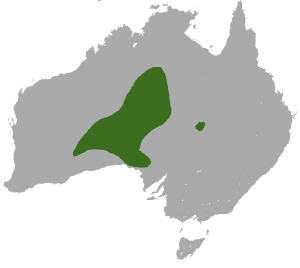

The habitat of the Southern Marsupial Mole is not well known, and is generally based on scattered records. It has been often recorded in sandy dunes or flats, usually where spinifex is present. Its habitat seems to be restricted to areas where the sand is soft, as it cannot tunnel through harder materials.[8] Although little is known about its exact distribution, sightings, aboriginal informants and museum records indicate that it lives in the central sandy desert regions of Western Australia, northern South Australia and the Northern Territory.[13] Recent studies indicate that its habitat also includes Great Victoria and Gibson Deserts.[14]

Behavior

Due to the lack of any field studies regarding the marsupial moles, there is little known about their behavior. Observations of captive animals are limited since most of the moles do not survive more than a little over a month after capture.

Surface behavior

It sometimes wanders above the surface where traces of several animals have been found. While most evidence indicates that it does this seldom and moves just a few meters before burrowing back underground, on some occasions multiple tracks were found suggesting that one or more animals have moved above ground for several hours. According to Aboriginal sources, marsupial moles may surface at any time of day, but seem to prefer to do so after rain and in the cooler season.[8]

Captive animals have been observed to feed above ground and then return underground to sleep. Occasionally it has been recorded to suddenly "faint" on the surface without waking up for several hours until disturbed.[15]

Above the ground it moves in a sinuous fashion, using its powerful forelimbs to haul the body over the surface and its hind limbs to push forward. The forelimbs are extended forward in unison with the opposite hind limb. Moles move about the surface with frantic haste but little speed, as one observer once likened it to a "Volkswagen Beetle heaving its way through the sand".[11]

Burrowing behavior

While burrowing, the Southern Marsupial Mole does not make permanent tunnels, but the sand caves in and tunnels back-fill as the animal moves along. For this reason its burrowing style has been compared to "swimming through the sand”". The only way its tunnels can be identified is as a small oval shape of lose sand. Although it spends most of its active time 20-100 cm below the surface, tunneling horizontally or at shallow angles, it sometimes for no apparent reason turns suddenly and burrows vertically to depths of up to 2.5 meters.[16]

Although most food sources are likely to occur at depths of approximately 50 cm from the surface, the temperature of these environments varies greatly from less than 15°C during winter to over 35°C during summer. While one of the captive moles was observed shivering when the temperature dropped under 16°C, it seems probable that moles can select the temperature of their environment by burrowing at different depths.[8]

Diet

Little is known about the Southern Marsupial Mole's diet, and all information is based on the gut content of preserved animals and on observations made on captive specimens. All evidence seems to suggest that the mole is mainly insectivorous, preferring insect eggs, larvae and pupae to the adults.[17] Based on observations made on captive animals, it seems that one of the favorite food choices was beetle larvae, especially Scarabaeidae.[15] Because burrowing requires high energy expenditure it seems unlikely that the mole searches for its food in this prey impoverished environment, and suggests that it probably feeds within nests. It has been also recorded to eat adult insects, seeds and lizards. Below the desert sands of Australia, the marsupial mole searches for burrowing insects and small reptiles. Instead of building a tunnel, it "swims" through the ground, allowing the sand to collapse behind it.[8]

Social behavior

There is little known about the social and reproductive behavior of these animals, but all evidence seems to suggest that it leads a solitary life. There are no traces of large burrows where more than one individual might meet and communicate. Although it is not known how the male locates the female, it is assumed that they do so using their highly developed olfactory sense.[12]

The fact that the middle ear seems to be morphologically suited for capturing low frequency sounds, and that moles produce high pitched vocalizations when handled, indicates that this kind of sound that propagates more easily underground may be used as a form of communication.[8]

Human interactions

The Southern Marsupial Mole was known for thousands of years to the aborigines and was part of their mythology. It was associated with certain sites and dreaming trails such as Uluru and the Anangu-Pitjantjatjara Lands. Aborigines regarded the creature with sympathy, probably due to its harmless nature, and it was only eaten in hard times. Aboriginal people have good tracking skills and generally cooperate with researchers in teaching them these skills and help finding specimens. Their involvement is instrumental in gathering information about the species’ habitat and behavior.[8]

Historical records suggest that the Southern Marsupial Mole was relatively common in the late 19th century and early 20th century. There was a large trade in marsupial mole skins in the Flike River region between 1900 and 1920. Large numbers of aborigines arrived at the trading post with 5-6 pelts each for sale to trade for food and other commodities. It is estimated that hundreds to several thousand skins were traded at these meetings, and that at the time the mole was relatively common.[11]

Conservation status

So little is known about the Southern Marsupial Mole that it is difficult to assess its exact distribution and how it varied over the last decades. However circumstantial evidence suggests that their numbers are dwindling. Although the decreasing acquisition rate is difficult to interpret due to the chance nature of the findings, there are reasons for concern. About 90% of medium sized marsupials in arid Australia have become threatened due to cat and fox predation. A recent study indicates that remains of marsupial moles have been found in 5% of the cats and foxes faecal pellets examined.[18] Moles are also sensitive to changes in the availability of their food caused by changing fire regimes and the impact of herbivores. The Southern Marsupial Mole is currently listed as endangered by the IUCN.[19] Efforts to protect this unique species focus on advocating for maintaining a healthy population of moles to better understand their biology and behavior, and for conducting field studies to monitor the species distribution and abundance with the help of Aborigines.[8]

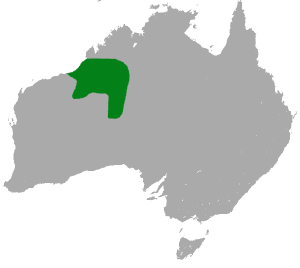

Northern marsupial mole

The Northern Marsupial Mole or Northwestern Marsupial Mole (Notoryctes caurinus) is a species of marsupial in the Notoryctidae family. It is endemic to Australia. Its natural habitat is hot deserts.[19] The Northern Marsupial Mole is yellow in color. Its diet consists of insect pupae and larvae. It lacks eyes and barely has ears.[20]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 C. Groves, "Order Primates," "Order Monotremata," (and select other orders). Page(s) 22 in D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder, eds., Mammal Species of the World, 3rd edition, Johns Hopkins University Press (2005). ISBN 0801882214.

- ↑ Mole Patrol. The Marsupial Society (2004). Retrieved 2006-11-09.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gordon, Greg (1984). in Macdonald, D.: The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ↑ Gott, M. (1988). A Tertiary marsupial mole (Marsupialia: Notoryctidae) from Riversleigh, northeastern Australia and its bearings on notoryctemorphian phylogenetics. Honours Thesis, University of Sydney, NSW.

- ↑ Calaby, J.H. (1974). The Chromosomes and Systematic Position of the Marsupial Mole, Notoryctes typhlops. Australian Journal of Biological Sciences 27 (5): 529–32.

- ↑ Westerman, M. (1991). Phylogenetic Relationships of the Marsupial Mole, Notoryctes typhlops (Marsupialia: Notoryctidae). Australian Journal of Zoology 39 (5): 529–37.

- ↑ Kirsch, J,A.W. (1997). DNA-hybridization studies of marsupials and their implications for metatherian classification. Australian Journal of Zoology 45 (3): 211–80.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 Benshemesh, John; Johnson, Ken (2003). in Jones, Menna; Dickman, Chris; Archer, Mike: Predators with pouches : the biology of carnivorous marsupials. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing, 464–474.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Thompson, Graham (2000). Blind Diggers in the Desert. Nature Australia 26: 26–31.

- ↑ Whitfield, Philip (1998). The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Animals. New York: Marshall Editions Development Limited, 25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Johnson, Ken (1991). The mole who comes from the sun. Wildlife Australia Spring: 8–9.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Johnson, Ken; Walton, Dan (1987). in D.W. Walton: Fauna of Australia v 1B Mammalia. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 591–603.

- ↑ Facts Sheet - Southern Marsupial Mole. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Pearson, David (2000). Marsupial Moles pop up in the Great Victoria and Gibson Deserts. Australian Mammology 22: 115–119.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Howe, D. (1973). Observations on a captive marsupial mole, Notoryctes typhlops. Australian Mammalogy 1 (4): 361–65.

- ↑ K.A. Johnson (1998). in Ronald Strahan: The mammals of Australia. Sydney: New Holland Publishers Pty Ltd, 409–11.

- ↑ Winkel, K. (1988). Diet of the Marsupial Mole, Notoryctes typhlops (Stirling 1889) (Marsupialia: Notoryctidae). Australian Mammology 11: 169–161.

- ↑ Paltridge, Rachel (1999). Occurrence of the Marsupial Mole (Notoryctes typhlops) remains in the faecal pellets of cats, foxes and dingoes in the Tanami Desert, N.T. Australian Mammalogy 20: 427–9.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namediucn - ↑ Northern Marsupial Mole

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2014. Notoryctemorphia Kirsch in Hunsaker, 1977. ITIS Report, Taxonomic Serial No.: 552296." Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- Wasleske, B. 2012. Notoryctes caurinus: Northern marsupial male. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- Glyshaw, P. 2011. Notoryctes typhlops: Southern marsupial male. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- Myers, P. 2001. Notoryctemorphia: Marsupial moles. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Wasleske, B. 2012. Notoryctes caurinus: Northern marsupial male. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

External links

- ARKive - images and movies of the marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops)

- Australian Geographic - The marsupial mole: an enduring enigma

| Mammals |

|---|

| Monotremata (platypus, echidnas) |

|

Marsupialia: | Paucituberculata (shrew opossums) | Didelphimorphia (opossums) | Microbiotheria | Notoryctemorphia (marsupial moles) | Dasyuromorphia (quolls and dunnarts) | Peramelemorphia (bilbies, bandicoots) | Diprotodontia (kangaroos and relatives) |

|

Placentalia: Cingulata (armadillos) | Pilosa (anteaters, sloths) | Afrosoricida (tenrecs, golden moles) | Macroscelidea (elephant shrews) | Tubulidentata (aardvark) | Hyracoidea (hyraxes) | Proboscidea (elephants) | Sirenia (dugongs, manatees) | Soricomorpha (shrews, moles) | Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs and relatives) Chiroptera (bats) | Pholidota (pangolins)| Carnivora | Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) | Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) | Cetacea (whales, dolphins) | Rodentia (rodents) | Lagomorpha (rabbits and relatives) | Scandentia (treeshrews) | Dermoptera (colugos) | Primates | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.