Difference between revisions of "Magic (Sorcery)" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→External links) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (49 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{2Copyedited}}{{copyedited}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Psychology]] | [[Category:Psychology]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Paranormal]] | ||

| + | [[Image:John William Waterhouse - Circe (The Sorceress).JPG|right|300 px|thumb|"The Sorceress" by [[John William Waterhouse]]]][[Image:John Dee evoking a spirit.jpg|right|300px|thumb|[[John Dee]] and [[Edward Kelley]] evoking a spirit: Elizabethans who claimed magical knowledge.]] | ||

| − | + | '''Magic,''' sometimes known as '''sorcery,''' is a [[conceptual system]] that asserts human ability to control [[nature|the natural world]] (including events, objects, people, and physical phenomena) through [[Mysticism|mystical]], [[paranormal]], or [[supernatural]] means. The term can also refer to the practices employed by a person asserting this influence, and to beliefs that explain various events and phenomena in such terms. In many cultures, magic is under pressure from, and in competition with, [[scientific]] and [[religious]] conceptual systems. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Although an effort is sometimes made to differentiate sorcery from [[magic_(Illusion)|magic performed for entertainment value]] by referring to sorcery as "magick," this article will consistently use "magic" in referring to sorcery. | |

| − | + | Magic has been used throughout history, in attempts to heal or harm others, to influence the weather or crops, and as part of [[religion|religious]] practices like [[shamanism]] and [[paganism]]. While magic has been feared and condemned by those of certain [[faith]]s and questioned by [[science|scientists]], it has survived both in belief and practice. Practitioners continue to use it for [[good]] or [[evil]], as magic itself is neither; but only a tool that is used according to the purpose of the one who wields it. The efficacy of magic continues to be debated, as both religious adherents and scientists find difficulty understanding the source of its power. | |

| − | + | Fundamental to magic is unseen connections whereby things act on one another at a distance through invisible links.<ref>David Levi Strauss, [http://brooklynrail.org/2006/07/film/magic-and-images Magic and Images/Images and Magic,] ''The Brooklyn Rail.'' Retrieved June 15, 2007.</ref> Magic is thus distinguished both from [[religion]] and [[science]]: From religion in that magic invokes spiritual powers without presuming any personal relationship with spiritual or divine beings, merely an ability or power to bring about particular results; and from science in that magic offers no empirical justification other than its efficacy, invoking a [[symbol]]ic, rather than actual, cause-effect relationship. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| + | While some deny any form of magic as authentic, those that practice it regard the influencing of events, objects, people, and physical phenomena through [[Mysticism|mystical]], [[paranormal]] or supernatural means as real. The fascination that [[magician]]s hold for the public reflects a longing to understand more than the external, physical aspects of the world and penetrate that which could give deeper meaning, the realm of spirit and magic. | ||

| − | + | == Etymology == | |

| − | + | The word '''magic''' derives from [[Magus]] ([[Old Persian]] ''maguš''), one of the [[Zoroastrian]] [[astrology|astrologer]] priests of the [[Medes]]. In the Hellenistic period, [[Greek language|Greek]] μάγος ''(magos)'' could be used as an adjective, but an adjective μαγικός (''magikos,'' [[Latin]] ''magicus'') is also attested from the first century ([[Plutarchus]]), typically appearing in the feminine, in μαγική τέχνη (''magike techne,'' Latin ''ars magica'') "magical art." The word entered the English language in the late fourteenth century from [[Old French]] ''magique''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The word ''magic'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Likewise, ''sorcery'' was taken in c. 1300 from Old French ''sorcerie,'' which is from [[Vulgar Latin]] ''sortiarius,'' from ''sors'' "fate," apparently meaning "one who influences fate." ''Sorceress'' appears also in the late fourteenth century, while ''sorcerer'' is attested only from 1526. | ||

| + | The Indo-European root of the word means “to be able, to have power”—really a verb of basic action and agency. | ||

== History == | == History == | ||

| − | |||

===Magic and early religion=== | ===Magic and early religion=== | ||

| − | + | The belief that influence can be exerted on supernatural powers through [[sacrifice]] or [[invocation]] goes back to [[prehistory|prehistoric times]]. It is present in the [[ancient Egypt|Egyptian]] [[pyramid texts]] and the [[India]]n ''[[Veda]]s,'' specifically the ''[[Atharvaveda]]'' ("knowledge of magic formulas"), which contains a number of [[charm]]s, sacrifices, hymns, and uses of [[herb]]s. It addresses topics including [[constipation]], [[disease]], [[possession]] by [[demon]]s, and the glorification of the [[sun]].<ref>Maurice Bloomfield, [http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/av.htm Hymns of the Atharva-Veda,] ''Sacred-texts.com.'' Retrieved May 21, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | The belief that influence can be | ||

| − | + | The prototypical "[[magician]]s" were a class of [[priest]]s, the [[Persia]]n [[Magus|Magi]] of [[Zoroastrianism]], who were highly learned and advanced in knowledge and crafts. This knowledge was likely mysterious to others, giving the Magi a reputation for sorcery and [[alchemy]].<ref>Stephan Williamson, [http://www.efn.org/~opal/templeofthemagi.html The Real Magi (Wise Men) and the True Star of Bethlehem.] Retrieved May 21, 2007.</ref> The ancient Greek [[mystery religion]]s had strongly magical components, and in Egypt, a large number of magical [[papyrus|papyri]] have been recovered. Dating as early as the second century B.C.E., the scrolls contain early instances of spells, incantations, and magical words composed of long strings of [[vowel]]s, and self-identification with a deity (the chanting of "I am [deity]," for example.) | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The roots of European magical practice are often claimed to originate in such Greek or Egyptian magic, but other scholars contest this theory, arguing that European magic may have drawn from a generalized magical tradition, but not from Egyptian magic specifically.<ref>Laurel Holmstrom, [http://www.sonoma.edu/users/h/holmstrl/EGmagic.html Self-identification with Deity and Voces Magicae in Ancient Egyptian and Greek Magic.] Retrieved May 21, 2007.</ref> In Europe, the [[Celts]] played a large role in early European magical tradition. Living between 700 B.C.E. and 100 C.E.., Celtics known as [[Druid]]s served as priests, teachers, judges, [[astrology|astrologers]], healers, and more. Rituals were often connected with [[agriculture|agricultural]] events and aspects of nature; [[tree]]s in particular were sacred to the Celts. Over time, the Celtic beliefs and practices grew into what would become known as [[Paganism]], mixed with other Indo-European beliefs, and became part of a set of beliefs and practices that were known collectively as "[[witchcraft]]." These practices included the concoction of [[potion]]s and ointments, [[spell]] casting, as well as other works of magic.<ref>Magikal Melting Pot, [http://www.magickalmeltingpot.com/History History of Magick.] Retrieved May 21, 2007.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Middle Ages === | ===Middle Ages === | ||

| − | + | The [[Middle Ages]] were characterized by the ubiquitousness and power of the [[Catholic Church]]. In the beginning of Europe's conversion to [[Christianity]], religious practices and beliefs were often appropriated and Christianized; for example, Christian rites and formulas were combined with Germanic folk rituals to cure ailments. Christian [[relic]]s replaced [[amulet]]s, and tales were told of the miracles these relics wrought. Churches that housed these relics became places of [[pilgrimage]]. Magic coexisted, often uneasily, with Christian theology for much of the early Middle Ages. | |

| − | + | By the fifteenth century, magicians were persecuted, as magical rites and beliefs were considered [[heresy]], a distortion of Christian rites to do the [[Devil]]'s work. [[Magician]]s were accused of ritualistic baby-killing and of having gained magical powers through pacts with the Devil.<ref>Encyclopedia Britannica Online, Magic.</ref> | |

| − | + | Despite this widespread condemnation of magical practice, a great number of magic formulas and books from the Middle Ages suggest that magic was widely practiced. Charms, amulets, [[divination]], [[astrology]], and the magical use of herbs and animals existed, as well as higher forms of magic such as [[alchemy]], [[necromancy]], [[astral]] magic, and more advanced forms of astrology. Magic also played a role in [[literature]]; most notably in the [[Arthurian romances]], where the magician [[Merlin]] advised [[King Arthur]].<ref>Ibid.</ref> [[Grimoires]], books of magical knowledge, like ''[[The Sworn Book of Honorius]],'' provided instructions on the [[conjuring]] and command of [[demon]]s, among other information. | |

===Renaissance === | ===Renaissance === | ||

| − | + | The [[Renaissance]] saw a resurgence in [[occultism]], which was saturated with the teachings of [[hermeticism]], which, along with [[Gnosticism]] and [[Neo-Platonism]], has formed the basis of most Western occult practices.<ref>Stephan Hoeller, [http://www.gnosis.org/hermes.htm On the Trail of the Winged God: Hermes and Hermeticism Throughout the Ages,] ''Gnosis.org''. Retrieved May 21, 2007.</ref> [[Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa]], a [[Germany|German]] born in 1486, was widely known for his books on magic and occultism. Most famous for his work ''De Occulta Philosophia'' ''(Occult Philosophy)'', Agrippa was an opportunist who mixed with royalty, founded secret societies, and went to debtor's prison. Even before his death, stories circulated about his prowess as a black magician, some of which were used by [[Goethe]] as inspiration for the title character of his play ''Faust''.<ref>''Occultopedia,'' [http://www.occultopedia.com/a/agrippa.htm Agrippa Von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius.] Retrieved July 24, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | [[Renaissance | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Barbara Radziwill ZjawaBarbary 19th century.jpg|left|thumb|250px|[[Pan Twardowski]] summoning the ghost of [[Barbara Radziwiłłówna]] for King [[Sigismund Augustus]], by [[Wojciech Gerson]].]] With the [[Industrial Revolution]], on the other hand, there was the rise of [[scientism]], in such forms as the substitution of [[chemistry]] for [[alchemy]], the dethronement of the [[Ptolemaic theory]] of the universe assumed by [[astrology]], and the development of the [[germ theory]] of [[disease]]. These developments both restricted the scope of applied magic and threatened the belief systems it relied on. Additionally, tensions roused by the [[Protestantism|Protestant]] [[Reformation]] led to an upswing in [[witch-hunt|witch-hunting]], especially in [[Germany]], [[England]], and [[Scotland]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | === Magic in the twentieth century === | + | ===Magic in the twentieth century=== |

| − | + | The twentieth century saw a dramatic revival of magical interest, particularly with the advent of [[neopaganism]]. [[Aleister Crowley]] wrote a number of works on magic and the occult, including the well known ''Book of the Law,'' which introduced Crowley's concept of "[[Thelema]]." The [[philosophy]] of Thelema is centered around one's "True Will;" one attempts to achieve the proper life course or innermost nature through magic. Thelemites follow two main laws: "Do what thou wilt," and "Love is the law, love under will." Crowley also advocated ritual and [[astral travel]], as well as keeping a "magical record," or diary of magical ceremonies.<ref>''Thelemapedia: The Encyclopedia of Thelema and Magick.''</ref> Crowley was also a member of the magical fraternity [[The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn]], an organization that had a great deal of influence on western occultism and ceremonial magic. | |

| − | + | ===The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn=== | |

| + | In 1888, [[freemasonry|freemasons]] William Westcott, William Woodman, and Samuel Mathers founded [[The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn]], a secret organization that was to be highly influential on the western practice of magic. The Golden Dawn was very organized, with [[ritual]]s and defined hierarchy, and attempted to structure a functional system of magic. Members, particularly Mathers, spent a great deal of time translating medieval [[grimoire]]s, writing material that combined [[ancient Egypt|Egyptian]] magic, Greco-Egyptian magic, and [[Jewish]] magic into a single working system. The Order taught [[astral travel]], [[scrying]], alchemy, astrology, the [[Tarot]], and [[geomancy]].<ref>''The Mystica,'' [http://www.themystica.com/mystica/articles/h/hermetic_order_of_the_golden_dawn.html Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.] Retrieved May 21, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Members attempted to develop their [[personality]] through their higher self, with the goal of achieving god-like status, through the manipulation of energies by the will and imagination. As might be expected, the large egos of many members created arguments, schisms, and alleged magical battles between Mathers and the [[Aleister Crowley]]. In 1903, [[William Butler Yeats]] took over leadership, renaming the group "The Holy Order of the Golden Dawn" and giving the group a more [[Christian]]-inspired philosophy. By 1914, however, there was little interest, and the organization was closed down.<ref>''Mysterious Britain,'' [http://www.mysteriousbritain.co.uk/occult/golden_dawn.html The Golden Dawn.] Retrieved July 24, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | [[ | + | ===Witchcraft and the New Age=== |

| + | In 1951, [[England]] repealed the last of the [[Witchcraft Acts]], which had previously made it against the law to practice witchcraft in the country. [[Gerald Gardner]], often referred to as the "father of modern witchcraft," published his first non-fiction book on magic, entitled ''Witchcraft Today,'' in 1954, which claimed modern witchcraft is the surviving remnant of an ancient Pagan religion. Gardner's novel inspired the formation of covens, and "[[Gardnerian Wicca]]" was firmly established.<ref>George Knowles, [http://www.controverscial.com/Gerald%20Brosseau%20Gardner.htm Gerald Brosseau Gardner (1884-1964).] Retrieved May 21, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The atmosphere of the 1960s and 1970s was conducive to the revival of interest in magic; the [[hippie]] [[counterculture]] sparked renewed interest in magic, divination, and other occult practices such as astrology. Various branches of [[Neopaganism]] and other [[Earth religion]]s combined magic with religion, and influenced each other. For instance, [[feminism|feminists]] launched an independent revival of [[goddess worship]], both influencing and being influenced by Gardnerian Wicca. Interest in magic can also be found in the [[New Age]] movement. Traditions and beliefs of different branches of neopaganism tend to vary, even within a particular group. Most focus on the development of the individual practitioner, not a need for strongly defined universal traditions or beliefs. | |

| − | + | ==Magicians== | |

| + | A magician is a person who practices the art of [[magic]], producing desired effects through the use of [[spell]]s, [[charm]]s, and other means. Magicians often claim to be able to manipulate [[supernatural]] entities or the forces of [[nature]]. Magicians have long been a source of fascination, and can be found in literature throughout most of history. | ||

| − | + | ===Magicians in legend and popular culture=== | |

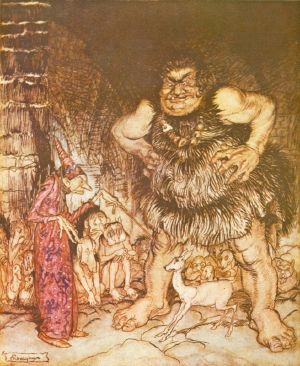

| − | The | + | [[Image:Galligantus - Project Gutenberg eText 17034.jpg|left|thumb|"The giant Galligantua and the wicked old magician transform the duke's daughter into a white hind." by [[Arthur Rackham]]; an evil wizard from the [[fairy tale]] ''Jack the Giant Killer''.]] |

| + | Wizards, magicians, and practitioners of magic by other titles have appeared in [[myth]]s, [[folktale]]s, and [[literature]] throughout recorded history, as well as modern [[fantasy]] and [[role-playing game]]s. They commonly appear as both mentors and villains, and are often portrayed as wielding great power. While some magicians acquired their skills through study or [[apprenticeship]], others were born with magical abilities. | ||

| − | + | Some magicians and wizards now understood to be fictional, such as the figure of [[Merlin]] from the [[Arthurian legend]]s, were once thought of as actual historical figures. While modern audiences often view magicians as wholly fictional, characters such as the witches in [[Shakespeare]]'s ''Macbeth'' and wizards like [[Prospero]] from ''The Tempest,'' were often historically considered to be as real as cooks or kings. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Wizards, who are often depicted with long, flowing white hair and beards, pointy hats, and robes covered with "sigils" (symbols created for a specific magical purpose), are often featured in often featured in fantasy novels and role-playing games. The wizard Gandalf in [[J.R.R. Tolkien]]'s ''Lord of the Rings'' trilogy is a well-known example of a magician who plays the role of mentor, much like the role of the wizard in [[medieval]] chivalric [[Romance (genre)|romance]]. Other witches and magicians can appear as villains, as hostile to the [[hero]] as [[ogre]]s and other monsters.<ref>Northrop Frye, ''Anatomy of Criticism'' (Princeton University Press, 2000). ISBN 0691069999</ref> Wizards and magicians often have specific props, such as a [[wand]], [[staff]], or [[crystal ball]], and may also have a [[familiar animal]] (an animal believed to be possessed of magic powers) living with them. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Ring40.jpg|right|thumb|Illustration by [[Arthur Rackham]] to [[Richard Wagner]]'s ''Siegfried'': [[Wotan]] visiting Mime]] | |

| + | There are significantly fewer female magicians or wizards in fiction. Female practitioners of magic are often called [[witch]]es, a term that generally denotes a lesser degree of schooling and type of magic, and often carries with it a negative connotation. Females who practice high level magic are sometimes referred to as enchantresses, such as [[Morgan le Fay]], half-sister to [[King Arthur]]. In contrast to the dignified, elderly depiction of wizards, enchantresses are often described as young and beautiful, although their youth is generally a magical illusion. | ||

| − | + | ==Types of magical rites== | |

| + | The best-known type of magical practice is the [[spell]], a [[ritual]]istic formula intended to bring about a specific effect. Spells are often spoken or written or physically constructed using a particular set of ingredients. The failure of a spell to work may be attributed to many causes, such as failure to follow the exact formula, general circumstances being unconducive, lack of magical ability, or downright [[fraud]]. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:John William Waterhouse - The Crystal Ball.JPG|right|thumb|"The Crystal Ball" by [[John William Waterhouse]]: using material for magical purposes; besides the crystal, a book and a wand.]] | |

| − | + | Another well-known magical practice is [[divination]], which seeks to reveal information about the past, present, or future. Varieties of divination include: [[Astrology]], [[Cartomancy]], [[Chiromancy]], [[Dowsing]], [[Fortune telling]], [[Geomancy]], [[I Ching]], [[Omen]]s, [[Scrying]], and [[Tarot]]. [[Necromancy]], the practice of summoning the dead, can also be used for divination, as well as an attempt to command the spirits of the dead for one's own purposes. | |

| − | + | Varieties of magic are often organized into categories, based on their technique or objective. British anthropologist [[Sir James Frazer]] described two categories of "sympathetic" magic: contagious and homeopathic. "Homeopathic" or "imitative" magic involves the use of images or physical objects which in some way resemble the person or thing one hopes to influence; attempting to harm a person by harming a [[photograph]] of said person is an example of homeopathic magic. Contagious magic involves the use of physical ingredients which were once in contact with the person or thing the practitioner intends to influence; contagious magic is thought to work on the principle that conjoined parts remain connected on a magical plane, even when separated by long distances. Frazer explained the process: | |

| + | <blockquote>If we analyze the principles of thought on which magic is based, they will probably be found to resolve themselves into two: first, that like produces like, or that an effect resembles its cause; and, second, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed. The former principle may be called the Law of Similarity, the latter the Law of Contact or Contagion. From the first of these principles, namely the Law of Similarity, the magician infers that he can produce any effect he desires merely by imitating it: from the second he infers that whatever he does to a material object will affect equally the person with whom the object was once in contact, whether it formed part of his body or not.<ref>Sir James George Frazer, [http://www.bartleby.com/196/5.html Sympathetic Magic: The Principles of Magic,] ''The Golden Bough.'' Retrieved May 22, 2007.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Contagious magic often uses body parts, such as hair, nail trimmings, and so forth, to work magic spells on a person. Often the two are used in conjunction: [[Voodoo]] dolls, for example, use homeopathic magic, but also often incorporate the hair or nails of a person into the doll. Both types of magic have been used in attempts to harm an enemy, as well as attempts to heal. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Another common set of categories given to magic is that of High and Low Magic. High magic, also called ceremonial magic, has the purpose of bringing the magician closer to the [[divine]]. Low magic, on the other hand, is more practical, and often has purposes involving [[money]], [[love]], and [[health]]. Low magic has often been considered to be more rooted in [[superstition]], and often was linked with [[witchcraft]].<ref>Catherine Beyer, [http://wicca.timerift.net/ceremonial_magic.shtml Definition: Ceremonial Magic,] ''Wicca for the Rest of Us.'' Retrieved May 22, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==The working of magic== | |

| + | Practitioners of magic often have a variety of items that are used for magical purposes. These can range from the staff or wand, which is often used in magical rites, to specific items called for by a certain spell or charm (the stereotypical "eye of newt," for example). Knives, [[symbol]]s like the [[circle]] or [[pentacle]], and [[altar]]s are often used in the performance of magical rites. | ||

| − | + | Depending on the magical tradition, the time of day, position of the [[star]]s, and direction all play a part in the successful working of a spell or rite. Magicians may use techniques to cleanse a space before performing magic, and may incorporate protective charms or [[amulet]]s. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The purpose of magic depends on the type of magic, as well as the individual magician. Some, like [[Aleister Crowley]], used magic to elevate the [[self]] and to join the [[human being|human]] with the [[divinity|divine]]. The use of magic is often connected with a desire for power and the importance of the self, particularly in the case of wizards and [[occultism|occultist]] magicians. Other groups, like [[Wicca]]ns, tend to be more concerned with the relation of the practitioner to the earth and the spiritual and physical worlds around them. | |

| − | == | + | ==Magical beliefs== |

| − | + | Practitioners of magic attribute the workings of magic to a number of different causes. Some believe in an undetectable, magical, natural force that exists in addition to forces like [[gravity]]. Others believe in a [[hierarchy]] of intervening [[spirit]]s, or mystical powers often contained in magical objects. Some believe in manipulation of the elements ([[fire]], [[air]], [[earth]], [[water]]); others believe that the manipulation of [[symbol]]s can alter the reality that the symbols represent. | |

| − | + | Aleister Crowley defined magic (or as he preferred, "magick") as "the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with the will." By this, he included "mundane" acts of will as well as [[ritual magick]], explaining the process: | |

| + | <blockquote>What is a Magical Operation? It may be defined as any event in nature which is brought to pass by Will. We must not exclude potato-growing or banking from our definition. Let us take a very simple example of a Magical Act: that of a man blowing his nose.<ref>Aleister Crowley, ''Magick in Theory and Practice'' (Book Sales, 1992). ISBN 1555217664</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Many, including Crowley, have believed that concentration or [[meditation]] can produce mental or mystical attainment; he likened the effect to that which occurred in "straightforward" [[Yoga]]. In addition to concentration, visualization is often used by practitioners of magic; some spells are cast while the practitioner is in a [[trance]] state. The power of the subconscious mind and the interconnectedness of all things are also concepts often found in magical thinking. | |

| − | + | ==Magical traditions in religion== | |

| + | Viewed from a non-theistic perspective, many [[religion|religious]] [[ritual]]s and beliefs seem similar to, or identical to, [[magical thinking]]. The repetition of [[prayer]] may seem closely related to the repetition of a charm or spell, however there are important differences. Religious beliefs and rituals may involve prayer or even [[sacrifice]] to a [[deity]], where the deity is petitioned to intervene on behalf of the supplicant. In this case, the deity has the choice: To grant or deny the request. Magic, in contrast, is effective in and of itself. In some cases, the magical rite itself contains the power. In others, the strength of the magician's will achieves the desired result, or the ability of the magician to command spiritual beings addressed by his/her spells. The power is contained in the magician or the magical rites, not a deity with a free will. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Pentagram_circumscribed.svg|thumb|left|The [[pentagram]] within a circle; a symbol used by many [[Wicca]]ns.]] | |

| + | While magic has been often practiced in its own right, it has also been a part of various religions. Often, religions like [[Voodoo]], [[Santeria]], and [[Wicca]] are mischaracterized as nothing more than forms of magic or sorcery. Magic is a part of these religions but does not define them, similar to how [[prayer]] and [[fasting]] may be part of other religions. | ||

| − | + | Magic has long been a associated with the practices of [[animism]] and [[shamanism]]. Shamanic contact with the [[spiritual world]] seems to be almost universal in tribal communities, including [[Australian Aborigine|Aboriginal]] tribes in [[Australia]], [[Maori]] tribes in [[New Zealand]], [[rainforest]] tribes in [[South America]], bush tribes in [[Africa]], and ancient [[Paganism|Pagan]] tribal groups in [[Europe]]. Ancient [[cave painting]]s in [[France]] are widely speculated to be early magical formulations, intended to produce successful hunts. Much of the [[Babylon]]ian and [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]]ian pictorial writing characters appear derived from the same sources. | |

| − | + | Traditional or folk magic is handed down from generation to generation. Not officially associated with any religion, folk magic includes practices like the use of [[horseshoe]]s for luck, or [[charm]]s to ward off evil spirits. Folk magic traditions are often associated with specific cultures. [[Hoodoo]], not to be confused with [[Voodoo]], is associated with African Americans, and incorporates the use of herbs and spells. [[Pow-wow]] is folk magic generally practiced by the [[Pennsylvania Dutch]], which includes charms, herbs, and the use of [[hex signs]]. | |

| − | + | While some organized religions embrace magic, others consider any sort of magical practice evil. [[Christianity]] and [[Islam]], for example, both denounce divination and other forms of magic as originating with the [[Devil]]. Contrary to much of magical practice, these religions advocate the submission of the will to a higher power ([[God]]). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Magic in theories of cultural evolution== | |

| + | [[Anthropology|Anthropologists]] have studied belief in magic in relationship to the development of [[culture]]s. The study of magic is often linked to the study of the development of [[religion]] in the hypothesized evolutionary progression from magic to religion to [[science]]. British [[ethnology|ethnologists]] [[Edward Burnett Tylor]] and [[James George Frazer]] proposed that belief in magic preceded religion.<ref>Barthelemy Comoe-Krou, [http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1310/is_1991_May/ai_10840021 Play and the Sacred in Africa—People at Play,] ''UNESCO Courier.'' Retrieved June 15, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | In 1902, [[Marcel Mauss]] published the anthropological classic ''A General Theory of Magic,'' a study of magic throughout various cultures. Mauss declared that, in order to be considered magical, a belief or act must be held by most people in a given society. In his view, magic is essentially traditional and social: “We held that sacred things, involved in sacrifice, did not constitute a system of propagated illusions, but were social, consequently real.”<ref>David Levi Strauss, [http://brooklynrail.org/2006/07/film/magic-and-images Magic and Images/Images and Magic,] ''The Brooklyn Rail.'' Retrieved June 15, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Sigmund Freud]]'s 1913 work, ''Totem and Taboo'', is an application of [[psychoanalysis]] to the fields of [[archaeology]], anthropology, and the study of religion. Freud pointed out striking parallels between the cultural practices of native tribal groups and the behavior patterns of [[neurosis|neurotics]]. In his third essay, entitled "Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts," Freud examined the [[animism]] and [[narcissism|narcissistic]] phase associated with a primitive understanding of the universe and early [[libido|libidinal]] development. According to his account, a belief in magic and sorcery derives from an overvaluation of physical acts whereby the structural conditions of [[mind]] are transposed onto the world. He proposed that this overvaluation survives in both primitive people and neurotics. The animistic mode of thinking is governed by an "omnipotence of thoughts," a [[projection (psychology)|projection]] of inner mental life onto the external world. This imaginary construction of reality is also discernible in [[obsession|obsessive]] thinking, [[delusional disorder]]s and [[phobia]]s. Freud commented that the omnipotence of such thoughts has been retained in the magical realm of [[art]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The well-known anthropologist [[Bronislaw Malinowski]] wrote ''The Role of Magic and Religion'' in 1913, describing the role magic plays in societies. According to Malinowski, magic enables simple societies to enact control over the natural environment; a role that is filled by [[technology]] in more complex and advanced societies. He noted that magic is generally used most often for issues concerning [[health]], and almost never used for domestic activities such as [[fire]] or basket making.<ref>Michael Arbuthnot, [http://www.teamatlantis.com/yucatan_test/research_magic_religion.html Article Review: The Role of Magic and Religion.] Retrieved June 15, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | Cultural anthropologist [[Edward E. Evans-Pritchard]] wrote the well-known ''Witchcraft: Oracles and Magic among the Azande'' in 1937. His approach was very different from that of Malinowski. In 1965, Evans-Pritchard published his seminal work ''Theories of Primitive Religion,'' where he argued that anthropologists should study cultures "from within," entering the minds of the people they studied, trying to understand the background of why people believe something or behave in a certain way. He claimed that believers and non-believers approach the study of religion in vastly different ways. Non-believers, he noted, are quick to come up with [[biology|biological]], [[sociology|sociological]], or [[psychology|psychological]] theories to explain religious experience as illusion, whereas believers are more likely to develop theories explaining religion as a method of conceptualizing and relating to reality. For believers, religion is a special dimension of reality. The same can be said of the study of magic. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Magic as good or evil== | ||

| + | Magic and magicians are often represented as [[evil]] and manipulative. Part of this may have to do with the historical [[demon]]ization of magic and [[witchcraft]], or, more simply, people's fear of what they do not understand. Many make a distinction between "black" magic and "white" magic; black magic being practiced for selfish, evil gains, and white magic for good. Others prefer not to use these terms, as the term "black magic" implies that the magic itself is evil. They note that magic can be compared to a tool, which can be put towards evil purposes by evil men, or beneficial purposes by good people. An axe is simply an axe; it can be used to kill, or it can be used to chop firewood and provide heat for a mother and her child. | ||

| + | While there have been practitioners of magic that have attempted to use magic for selfish gain or to harm others, most practitioners of magic believe in some form of [[karma]]; whatever energy they put out into the world will be returned to them. [[Wicca]]ns, for example, often believe in the [[Rule of Three]]; whatever one sends out into the world will be returned three times. Malicious actions or spells, then, would then hurt the sender more than the recipient. [[Voodoo]] dolls, often represented as a means of hurting or even killing an enemy, are often used for healing and good luck in different areas of one's life. | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | < | + | <references/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Clifton, Dan Salahuddin. 1998. ''Myth Of The Western Magical Tradition''. ISBN 0393001431 | |

| − | + | * Crowley, Aleister. 1991. ''Magick Without Tears''. New Falcon Publications. ISBN 1561840181 | |

| − | + | * Crowley, Aleister. 1989. ''The Holy Books of Thelema''. Weiser Books. ISBN 0877286868 | |

| − | + | * de Givry, Grillot. 1954. ''Witchcraft, Magic, and Alchemy''. Frederick Pub. | |

| − | * | + | * Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1937. ''Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande.'' Clarendon Press. |

| − | + | * Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1965. ''Theories of Primitive Religion.'' Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198231318 | |

| − | + | * Frazer, J. G. 1911. ''The Golden Bough.'' London. | |

| − | + | * Freud, Sigmund. [1913] 2001. ''Totem and Taboo''. Routledge. ISBN 041525387X | |

| − | * | + | * Hutton, Ronald. 2001. ''The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft''. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-285449-6 |

| − | + | * Hutton, Ronald. 2003. ''Witches, Druids, and King Arthur''. Hambledon. ISBN 1-85285-397-2 | |

| − | * | + | * Kampf, Erich. 1894. ''The Plains of Magic.'' Konte Publishing. |

| − | + | * Kiekhefer, Richard. 1998. ''Forbidden Rites: A Necromancer's Manual of the Fifteenth Century''. Pennsylvania State University. ISBN 0-271-01751-1. | |

| − | * Hutton, Ronald | + | * Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1992. ''Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays''. Waveland Press. ISBN 0881336572 |

| − | + | * Mauss, Marcel. [1902] 2001. ''General Theory of Magic''. Routledge. ISBN 0415253969 | |

| − | * Kampf, Erich | + | * Martin, Philip. ''The Writer's Guide to Fantasy Literature: From Dragon's Lair to Hero's Quest''. ISBN 0-87116-195-8 |

| − | + | * Regardie, Israel. 2002. ''Golden Dawn: The Original Account of the Teachings, Rites & Ceremonies of the Hermetic Order''. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 0875426638 | |

| − | * | + | * Ruickbie, Leo. 2004. ''Witchcraft Out of the Shadows''. Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-7567-7 |

| − | + | * Thomas, N. W. 1911. "Magic." ''Encyclopedia Britannica.'' | |

| − | * [ | + | * Wrede, Patricia. "Magic and Magicians." ''Fantasy Worldbuilding Questions'' |

| − | |||

| − | * Thomas, N. W. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 5, 2022. | ||

| + | * [http://skepdic.com/magicalthinking.html "Magical Thinking"] ''The Skeptic's Dictionary'' | ||

| + | * [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11197b.htm "Occult Art, Occultism"] ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' | ||

| + | * [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15674a.htm "Witchcraft"] ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' | ||

| − | + | {{Credits|Magic_(paranormal)|125935766|Magic_(paranormal)|176450609|Magician_(paranormal)|110640950|Magician_(fantasy)|125967066|}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{Credits|Magic_(paranormal)|125935766|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 10:49, 9 March 2023

Magic, sometimes known as sorcery, is a conceptual system that asserts human ability to control the natural world (including events, objects, people, and physical phenomena) through mystical, paranormal, or supernatural means. The term can also refer to the practices employed by a person asserting this influence, and to beliefs that explain various events and phenomena in such terms. In many cultures, magic is under pressure from, and in competition with, scientific and religious conceptual systems.

Although an effort is sometimes made to differentiate sorcery from magic performed for entertainment value by referring to sorcery as "magick," this article will consistently use "magic" in referring to sorcery.

Magic has been used throughout history, in attempts to heal or harm others, to influence the weather or crops, and as part of religious practices like shamanism and paganism. While magic has been feared and condemned by those of certain faiths and questioned by scientists, it has survived both in belief and practice. Practitioners continue to use it for good or evil, as magic itself is neither; but only a tool that is used according to the purpose of the one who wields it. The efficacy of magic continues to be debated, as both religious adherents and scientists find difficulty understanding the source of its power.

Fundamental to magic is unseen connections whereby things act on one another at a distance through invisible links.[1] Magic is thus distinguished both from religion and science: From religion in that magic invokes spiritual powers without presuming any personal relationship with spiritual or divine beings, merely an ability or power to bring about particular results; and from science in that magic offers no empirical justification other than its efficacy, invoking a symbolic, rather than actual, cause-effect relationship.

While some deny any form of magic as authentic, those that practice it regard the influencing of events, objects, people, and physical phenomena through mystical, paranormal or supernatural means as real. The fascination that magicians hold for the public reflects a longing to understand more than the external, physical aspects of the world and penetrate that which could give deeper meaning, the realm of spirit and magic.

Etymology

The word magic derives from Magus (Old Persian maguš), one of the Zoroastrian astrologer priests of the Medes. In the Hellenistic period, Greek μάγος (magos) could be used as an adjective, but an adjective μαγικός (magikos, Latin magicus) is also attested from the first century (Plutarchus), typically appearing in the feminine, in μαγική τέχνη (magike techne, Latin ars magica) "magical art." The word entered the English language in the late fourteenth century from Old French magique.

Likewise, sorcery was taken in c. 1300 from Old French sorcerie, which is from Vulgar Latin sortiarius, from sors "fate," apparently meaning "one who influences fate." Sorceress appears also in the late fourteenth century, while sorcerer is attested only from 1526.

The Indo-European root of the word means “to be able, to have power”—really a verb of basic action and agency.

History

Magic and early religion

The belief that influence can be exerted on supernatural powers through sacrifice or invocation goes back to prehistoric times. It is present in the Egyptian pyramid texts and the Indian Vedas, specifically the Atharvaveda ("knowledge of magic formulas"), which contains a number of charms, sacrifices, hymns, and uses of herbs. It addresses topics including constipation, disease, possession by demons, and the glorification of the sun.[2]

The prototypical "magicians" were a class of priests, the Persian Magi of Zoroastrianism, who were highly learned and advanced in knowledge and crafts. This knowledge was likely mysterious to others, giving the Magi a reputation for sorcery and alchemy.[3] The ancient Greek mystery religions had strongly magical components, and in Egypt, a large number of magical papyri have been recovered. Dating as early as the second century B.C.E., the scrolls contain early instances of spells, incantations, and magical words composed of long strings of vowels, and self-identification with a deity (the chanting of "I am [deity]," for example.)

The roots of European magical practice are often claimed to originate in such Greek or Egyptian magic, but other scholars contest this theory, arguing that European magic may have drawn from a generalized magical tradition, but not from Egyptian magic specifically.[4] In Europe, the Celts played a large role in early European magical tradition. Living between 700 B.C.E. and 100 C.E., Celtics known as Druids served as priests, teachers, judges, astrologers, healers, and more. Rituals were often connected with agricultural events and aspects of nature; trees in particular were sacred to the Celts. Over time, the Celtic beliefs and practices grew into what would become known as Paganism, mixed with other Indo-European beliefs, and became part of a set of beliefs and practices that were known collectively as "witchcraft." These practices included the concoction of potions and ointments, spell casting, as well as other works of magic.[5]

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages were characterized by the ubiquitousness and power of the Catholic Church. In the beginning of Europe's conversion to Christianity, religious practices and beliefs were often appropriated and Christianized; for example, Christian rites and formulas were combined with Germanic folk rituals to cure ailments. Christian relics replaced amulets, and tales were told of the miracles these relics wrought. Churches that housed these relics became places of pilgrimage. Magic coexisted, often uneasily, with Christian theology for much of the early Middle Ages.

By the fifteenth century, magicians were persecuted, as magical rites and beliefs were considered heresy, a distortion of Christian rites to do the Devil's work. Magicians were accused of ritualistic baby-killing and of having gained magical powers through pacts with the Devil.[6]

Despite this widespread condemnation of magical practice, a great number of magic formulas and books from the Middle Ages suggest that magic was widely practiced. Charms, amulets, divination, astrology, and the magical use of herbs and animals existed, as well as higher forms of magic such as alchemy, necromancy, astral magic, and more advanced forms of astrology. Magic also played a role in literature; most notably in the Arthurian romances, where the magician Merlin advised King Arthur.[7] Grimoires, books of magical knowledge, like The Sworn Book of Honorius, provided instructions on the conjuring and command of demons, among other information.

Renaissance

The Renaissance saw a resurgence in occultism, which was saturated with the teachings of hermeticism, which, along with Gnosticism and Neo-Platonism, has formed the basis of most Western occult practices.[8] Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, a German born in 1486, was widely known for his books on magic and occultism. Most famous for his work De Occulta Philosophia (Occult Philosophy), Agrippa was an opportunist who mixed with royalty, founded secret societies, and went to debtor's prison. Even before his death, stories circulated about his prowess as a black magician, some of which were used by Goethe as inspiration for the title character of his play Faust.[9]

With the Industrial Revolution, on the other hand, there was the rise of scientism, in such forms as the substitution of chemistry for alchemy, the dethronement of the Ptolemaic theory of the universe assumed by astrology, and the development of the germ theory of disease. These developments both restricted the scope of applied magic and threatened the belief systems it relied on. Additionally, tensions roused by the Protestant Reformation led to an upswing in witch-hunting, especially in Germany, England, and Scotland.

Magic in the twentieth century

The twentieth century saw a dramatic revival of magical interest, particularly with the advent of neopaganism. Aleister Crowley wrote a number of works on magic and the occult, including the well known Book of the Law, which introduced Crowley's concept of "Thelema." The philosophy of Thelema is centered around one's "True Will;" one attempts to achieve the proper life course or innermost nature through magic. Thelemites follow two main laws: "Do what thou wilt," and "Love is the law, love under will." Crowley also advocated ritual and astral travel, as well as keeping a "magical record," or diary of magical ceremonies.[10] Crowley was also a member of the magical fraternity The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an organization that had a great deal of influence on western occultism and ceremonial magic.

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

In 1888, freemasons William Westcott, William Woodman, and Samuel Mathers founded The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret organization that was to be highly influential on the western practice of magic. The Golden Dawn was very organized, with rituals and defined hierarchy, and attempted to structure a functional system of magic. Members, particularly Mathers, spent a great deal of time translating medieval grimoires, writing material that combined Egyptian magic, Greco-Egyptian magic, and Jewish magic into a single working system. The Order taught astral travel, scrying, alchemy, astrology, the Tarot, and geomancy.[11]

Members attempted to develop their personality through their higher self, with the goal of achieving god-like status, through the manipulation of energies by the will and imagination. As might be expected, the large egos of many members created arguments, schisms, and alleged magical battles between Mathers and the Aleister Crowley. In 1903, William Butler Yeats took over leadership, renaming the group "The Holy Order of the Golden Dawn" and giving the group a more Christian-inspired philosophy. By 1914, however, there was little interest, and the organization was closed down.[12]

Witchcraft and the New Age

In 1951, England repealed the last of the Witchcraft Acts, which had previously made it against the law to practice witchcraft in the country. Gerald Gardner, often referred to as the "father of modern witchcraft," published his first non-fiction book on magic, entitled Witchcraft Today, in 1954, which claimed modern witchcraft is the surviving remnant of an ancient Pagan religion. Gardner's novel inspired the formation of covens, and "Gardnerian Wicca" was firmly established.[13]

The atmosphere of the 1960s and 1970s was conducive to the revival of interest in magic; the hippie counterculture sparked renewed interest in magic, divination, and other occult practices such as astrology. Various branches of Neopaganism and other Earth religions combined magic with religion, and influenced each other. For instance, feminists launched an independent revival of goddess worship, both influencing and being influenced by Gardnerian Wicca. Interest in magic can also be found in the New Age movement. Traditions and beliefs of different branches of neopaganism tend to vary, even within a particular group. Most focus on the development of the individual practitioner, not a need for strongly defined universal traditions or beliefs.

Magicians

A magician is a person who practices the art of magic, producing desired effects through the use of spells, charms, and other means. Magicians often claim to be able to manipulate supernatural entities or the forces of nature. Magicians have long been a source of fascination, and can be found in literature throughout most of history.

Magicians in legend and popular culture

Wizards, magicians, and practitioners of magic by other titles have appeared in myths, folktales, and literature throughout recorded history, as well as modern fantasy and role-playing games. They commonly appear as both mentors and villains, and are often portrayed as wielding great power. While some magicians acquired their skills through study or apprenticeship, others were born with magical abilities.

Some magicians and wizards now understood to be fictional, such as the figure of Merlin from the Arthurian legends, were once thought of as actual historical figures. While modern audiences often view magicians as wholly fictional, characters such as the witches in Shakespeare's Macbeth and wizards like Prospero from The Tempest, were often historically considered to be as real as cooks or kings.

Wizards, who are often depicted with long, flowing white hair and beards, pointy hats, and robes covered with "sigils" (symbols created for a specific magical purpose), are often featured in often featured in fantasy novels and role-playing games. The wizard Gandalf in J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy is a well-known example of a magician who plays the role of mentor, much like the role of the wizard in medieval chivalric romance. Other witches and magicians can appear as villains, as hostile to the hero as ogres and other monsters.[14] Wizards and magicians often have specific props, such as a wand, staff, or crystal ball, and may also have a familiar animal (an animal believed to be possessed of magic powers) living with them.

There are significantly fewer female magicians or wizards in fiction. Female practitioners of magic are often called witches, a term that generally denotes a lesser degree of schooling and type of magic, and often carries with it a negative connotation. Females who practice high level magic are sometimes referred to as enchantresses, such as Morgan le Fay, half-sister to King Arthur. In contrast to the dignified, elderly depiction of wizards, enchantresses are often described as young and beautiful, although their youth is generally a magical illusion.

Types of magical rites

The best-known type of magical practice is the spell, a ritualistic formula intended to bring about a specific effect. Spells are often spoken or written or physically constructed using a particular set of ingredients. The failure of a spell to work may be attributed to many causes, such as failure to follow the exact formula, general circumstances being unconducive, lack of magical ability, or downright fraud.

Another well-known magical practice is divination, which seeks to reveal information about the past, present, or future. Varieties of divination include: Astrology, Cartomancy, Chiromancy, Dowsing, Fortune telling, Geomancy, I Ching, Omens, Scrying, and Tarot. Necromancy, the practice of summoning the dead, can also be used for divination, as well as an attempt to command the spirits of the dead for one's own purposes.

Varieties of magic are often organized into categories, based on their technique or objective. British anthropologist Sir James Frazer described two categories of "sympathetic" magic: contagious and homeopathic. "Homeopathic" or "imitative" magic involves the use of images or physical objects which in some way resemble the person or thing one hopes to influence; attempting to harm a person by harming a photograph of said person is an example of homeopathic magic. Contagious magic involves the use of physical ingredients which were once in contact with the person or thing the practitioner intends to influence; contagious magic is thought to work on the principle that conjoined parts remain connected on a magical plane, even when separated by long distances. Frazer explained the process:

If we analyze the principles of thought on which magic is based, they will probably be found to resolve themselves into two: first, that like produces like, or that an effect resembles its cause; and, second, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed. The former principle may be called the Law of Similarity, the latter the Law of Contact or Contagion. From the first of these principles, namely the Law of Similarity, the magician infers that he can produce any effect he desires merely by imitating it: from the second he infers that whatever he does to a material object will affect equally the person with whom the object was once in contact, whether it formed part of his body or not.[15]

Contagious magic often uses body parts, such as hair, nail trimmings, and so forth, to work magic spells on a person. Often the two are used in conjunction: Voodoo dolls, for example, use homeopathic magic, but also often incorporate the hair or nails of a person into the doll. Both types of magic have been used in attempts to harm an enemy, as well as attempts to heal.

Another common set of categories given to magic is that of High and Low Magic. High magic, also called ceremonial magic, has the purpose of bringing the magician closer to the divine. Low magic, on the other hand, is more practical, and often has purposes involving money, love, and health. Low magic has often been considered to be more rooted in superstition, and often was linked with witchcraft.[16]

The working of magic

Practitioners of magic often have a variety of items that are used for magical purposes. These can range from the staff or wand, which is often used in magical rites, to specific items called for by a certain spell or charm (the stereotypical "eye of newt," for example). Knives, symbols like the circle or pentacle, and altars are often used in the performance of magical rites.

Depending on the magical tradition, the time of day, position of the stars, and direction all play a part in the successful working of a spell or rite. Magicians may use techniques to cleanse a space before performing magic, and may incorporate protective charms or amulets.

The purpose of magic depends on the type of magic, as well as the individual magician. Some, like Aleister Crowley, used magic to elevate the self and to join the human with the divine. The use of magic is often connected with a desire for power and the importance of the self, particularly in the case of wizards and occultist magicians. Other groups, like Wiccans, tend to be more concerned with the relation of the practitioner to the earth and the spiritual and physical worlds around them.

Magical beliefs

Practitioners of magic attribute the workings of magic to a number of different causes. Some believe in an undetectable, magical, natural force that exists in addition to forces like gravity. Others believe in a hierarchy of intervening spirits, or mystical powers often contained in magical objects. Some believe in manipulation of the elements (fire, air, earth, water); others believe that the manipulation of symbols can alter the reality that the symbols represent.

Aleister Crowley defined magic (or as he preferred, "magick") as "the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with the will." By this, he included "mundane" acts of will as well as ritual magick, explaining the process:

What is a Magical Operation? It may be defined as any event in nature which is brought to pass by Will. We must not exclude potato-growing or banking from our definition. Let us take a very simple example of a Magical Act: that of a man blowing his nose.[17]

Many, including Crowley, have believed that concentration or meditation can produce mental or mystical attainment; he likened the effect to that which occurred in "straightforward" Yoga. In addition to concentration, visualization is often used by practitioners of magic; some spells are cast while the practitioner is in a trance state. The power of the subconscious mind and the interconnectedness of all things are also concepts often found in magical thinking.

Magical traditions in religion

Viewed from a non-theistic perspective, many religious rituals and beliefs seem similar to, or identical to, magical thinking. The repetition of prayer may seem closely related to the repetition of a charm or spell, however there are important differences. Religious beliefs and rituals may involve prayer or even sacrifice to a deity, where the deity is petitioned to intervene on behalf of the supplicant. In this case, the deity has the choice: To grant or deny the request. Magic, in contrast, is effective in and of itself. In some cases, the magical rite itself contains the power. In others, the strength of the magician's will achieves the desired result, or the ability of the magician to command spiritual beings addressed by his/her spells. The power is contained in the magician or the magical rites, not a deity with a free will.

While magic has been often practiced in its own right, it has also been a part of various religions. Often, religions like Voodoo, Santeria, and Wicca are mischaracterized as nothing more than forms of magic or sorcery. Magic is a part of these religions but does not define them, similar to how prayer and fasting may be part of other religions.

Magic has long been a associated with the practices of animism and shamanism. Shamanic contact with the spiritual world seems to be almost universal in tribal communities, including Aboriginal tribes in Australia, Maori tribes in New Zealand, rainforest tribes in South America, bush tribes in Africa, and ancient Pagan tribal groups in Europe. Ancient cave paintings in France are widely speculated to be early magical formulations, intended to produce successful hunts. Much of the Babylonian and Egyptian pictorial writing characters appear derived from the same sources.

Traditional or folk magic is handed down from generation to generation. Not officially associated with any religion, folk magic includes practices like the use of horseshoes for luck, or charms to ward off evil spirits. Folk magic traditions are often associated with specific cultures. Hoodoo, not to be confused with Voodoo, is associated with African Americans, and incorporates the use of herbs and spells. Pow-wow is folk magic generally practiced by the Pennsylvania Dutch, which includes charms, herbs, and the use of hex signs.

While some organized religions embrace magic, others consider any sort of magical practice evil. Christianity and Islam, for example, both denounce divination and other forms of magic as originating with the Devil. Contrary to much of magical practice, these religions advocate the submission of the will to a higher power (God).

Magic in theories of cultural evolution

Anthropologists have studied belief in magic in relationship to the development of cultures. The study of magic is often linked to the study of the development of religion in the hypothesized evolutionary progression from magic to religion to science. British ethnologists Edward Burnett Tylor and James George Frazer proposed that belief in magic preceded religion.[18]

In 1902, Marcel Mauss published the anthropological classic A General Theory of Magic, a study of magic throughout various cultures. Mauss declared that, in order to be considered magical, a belief or act must be held by most people in a given society. In his view, magic is essentially traditional and social: “We held that sacred things, involved in sacrifice, did not constitute a system of propagated illusions, but were social, consequently real.”[19]

Sigmund Freud's 1913 work, Totem and Taboo, is an application of psychoanalysis to the fields of archaeology, anthropology, and the study of religion. Freud pointed out striking parallels between the cultural practices of native tribal groups and the behavior patterns of neurotics. In his third essay, entitled "Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts," Freud examined the animism and narcissistic phase associated with a primitive understanding of the universe and early libidinal development. According to his account, a belief in magic and sorcery derives from an overvaluation of physical acts whereby the structural conditions of mind are transposed onto the world. He proposed that this overvaluation survives in both primitive people and neurotics. The animistic mode of thinking is governed by an "omnipotence of thoughts," a projection of inner mental life onto the external world. This imaginary construction of reality is also discernible in obsessive thinking, delusional disorders and phobias. Freud commented that the omnipotence of such thoughts has been retained in the magical realm of art.

The well-known anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski wrote The Role of Magic and Religion in 1913, describing the role magic plays in societies. According to Malinowski, magic enables simple societies to enact control over the natural environment; a role that is filled by technology in more complex and advanced societies. He noted that magic is generally used most often for issues concerning health, and almost never used for domestic activities such as fire or basket making.[20]

Cultural anthropologist Edward E. Evans-Pritchard wrote the well-known Witchcraft: Oracles and Magic among the Azande in 1937. His approach was very different from that of Malinowski. In 1965, Evans-Pritchard published his seminal work Theories of Primitive Religion, where he argued that anthropologists should study cultures "from within," entering the minds of the people they studied, trying to understand the background of why people believe something or behave in a certain way. He claimed that believers and non-believers approach the study of religion in vastly different ways. Non-believers, he noted, are quick to come up with biological, sociological, or psychological theories to explain religious experience as illusion, whereas believers are more likely to develop theories explaining religion as a method of conceptualizing and relating to reality. For believers, religion is a special dimension of reality. The same can be said of the study of magic.

Magic as good or evil

Magic and magicians are often represented as evil and manipulative. Part of this may have to do with the historical demonization of magic and witchcraft, or, more simply, people's fear of what they do not understand. Many make a distinction between "black" magic and "white" magic; black magic being practiced for selfish, evil gains, and white magic for good. Others prefer not to use these terms, as the term "black magic" implies that the magic itself is evil. They note that magic can be compared to a tool, which can be put towards evil purposes by evil men, or beneficial purposes by good people. An axe is simply an axe; it can be used to kill, or it can be used to chop firewood and provide heat for a mother and her child.

While there have been practitioners of magic that have attempted to use magic for selfish gain or to harm others, most practitioners of magic believe in some form of karma; whatever energy they put out into the world will be returned to them. Wiccans, for example, often believe in the Rule of Three; whatever one sends out into the world will be returned three times. Malicious actions or spells, then, would then hurt the sender more than the recipient. Voodoo dolls, often represented as a means of hurting or even killing an enemy, are often used for healing and good luck in different areas of one's life.

Notes

- ↑ David Levi Strauss, Magic and Images/Images and Magic, The Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- ↑ Maurice Bloomfield, Hymns of the Atharva-Veda, Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ↑ Stephan Williamson, The Real Magi (Wise Men) and the True Star of Bethlehem. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ↑ Laurel Holmstrom, Self-identification with Deity and Voces Magicae in Ancient Egyptian and Greek Magic. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ↑ Magikal Melting Pot, History of Magick. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica Online, Magic.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Stephan Hoeller, On the Trail of the Winged God: Hermes and Hermeticism Throughout the Ages, Gnosis.org. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ↑ Occultopedia, Agrippa Von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ↑ Thelemapedia: The Encyclopedia of Thelema and Magick.

- ↑ The Mystica, Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ↑ Mysterious Britain, The Golden Dawn. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ↑ George Knowles, Gerald Brosseau Gardner (1884-1964). Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ↑ Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (Princeton University Press, 2000). ISBN 0691069999

- ↑ Sir James George Frazer, Sympathetic Magic: The Principles of Magic, The Golden Bough. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ↑ Catherine Beyer, Definition: Ceremonial Magic, Wicca for the Rest of Us. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ↑ Aleister Crowley, Magick in Theory and Practice (Book Sales, 1992). ISBN 1555217664

- ↑ Barthelemy Comoe-Krou, Play and the Sacred in Africa—People at Play, UNESCO Courier. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- ↑ David Levi Strauss, Magic and Images/Images and Magic, The Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- ↑ Michael Arbuthnot, Article Review: The Role of Magic and Religion. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Clifton, Dan Salahuddin. 1998. Myth Of The Western Magical Tradition. ISBN 0393001431

- Crowley, Aleister. 1991. Magick Without Tears. New Falcon Publications. ISBN 1561840181

- Crowley, Aleister. 1989. The Holy Books of Thelema. Weiser Books. ISBN 0877286868

- de Givry, Grillot. 1954. Witchcraft, Magic, and Alchemy. Frederick Pub.

- Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1937. Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande. Clarendon Press.

- Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1965. Theories of Primitive Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198231318

- Frazer, J. G. 1911. The Golden Bough. London.

- Freud, Sigmund. [1913] 2001. Totem and Taboo. Routledge. ISBN 041525387X

- Hutton, Ronald. 2001. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-285449-6

- Hutton, Ronald. 2003. Witches, Druids, and King Arthur. Hambledon. ISBN 1-85285-397-2

- Kampf, Erich. 1894. The Plains of Magic. Konte Publishing.

- Kiekhefer, Richard. 1998. Forbidden Rites: A Necromancer's Manual of the Fifteenth Century. Pennsylvania State University. ISBN 0-271-01751-1.

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1992. Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. Waveland Press. ISBN 0881336572

- Mauss, Marcel. [1902] 2001. General Theory of Magic. Routledge. ISBN 0415253969

- Martin, Philip. The Writer's Guide to Fantasy Literature: From Dragon's Lair to Hero's Quest. ISBN 0-87116-195-8

- Regardie, Israel. 2002. Golden Dawn: The Original Account of the Teachings, Rites & Ceremonies of the Hermetic Order. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 0875426638

- Ruickbie, Leo. 2004. Witchcraft Out of the Shadows. Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-7567-7

- Thomas, N. W. 1911. "Magic." Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Wrede, Patricia. "Magic and Magicians." Fantasy Worldbuilding Questions

External links

All links retrieved November 5, 2022.

- "Magical Thinking" The Skeptic's Dictionary

- "Occult Art, Occultism" Catholic Encyclopedia

- "Witchcraft" Catholic Encyclopedia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Magic_(paranormal) history

- Magic_(paranormal) history

- Magician_(paranormal) history

- Magician_(fantasy) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.