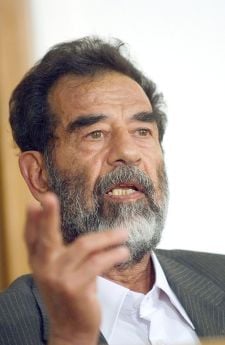

Saddam Hussein

5th President of Iraq | |

| Term┬áof┬áoffice | July 16, 1979┬áÔÇô┬áApril 9, 2003 |

| Preceded by | Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr |

| Succeeded by | Coalition Provisional Authority |

| Date of birth | April 28, 1937 |

| Place of birth | Al-Awja, Iraq |

| Date of death | December 30, 2006 |

| Place of death | Kazimiyah, Iraq |

| Spouse | Sajida Talfah |

| Political party | Ba'ath Arab Socialist Party |

Saddam Hussein Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti[1](ěÁě»ěž┘ů ěşě│┘Ő┘ć ě╣ěĘě» ěž┘ä┘ůěČ┘Őě» ěž┘äě¬┘âě▒┘Őě¬┘Ő); April 28, 1937[2], was the President of Iraq from July 16, 1979, until April 9, 2003.

As vice president under his cousin, General Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, Saddam tightly controlled conflict between the government and the armed forces by creating repressive security forces and cementing his own authority over the apparatus of government.

As president and head of the Baath Party, Saddam espoused secular pan-Arabism, economic modernization, and Arab socialism. Meanwhile, he consolidated one-party rule and maintained power through the Iran-Iraq War (1980ÔÇô1988) and the Gulf War (1991). Saddam repressed movements he deemed threatening to the stability of his rule, particularly those of ethnic or religious groups that sought independence or autonomy, including Iraq's Shi'a Muslim, Kurdish and Iraqi Turkmen populations.

Saddam's government collapsed as a result of the 2003 invasion of Iraq by an international coalition led by the United States, and he was captured by American forces on December 13, 2003. On November 5, 2006, he was convicted of crimes against humanity by the Iraq Special Tribunal and sentenced to death by hanging.

On December 26, 2006, Saddam's appeal was rejected and the death sentence upheld. His execution, at approximately 6:00 A.M. on December 30, 2006 was witnessed by lawyers, officials, and by a physician.

Youth

Saddam Hussein Takrity was born in the town of Al-Awja, 13 km (8 mi) from the Iraqi town of Tikrit to a family of shepherds from the al-Begat tribal group. His mother, Subha Tulfah al-Mussallat, named her newborn son Saddam, which in Arabic means ÔÇťOne who confronts.ÔÇŁ He never knew his father, Hussein 'Abd al-Majid, who disappeared six months before Saddam was born. Shortly afterward, Saddam's 13-year-old brother died of cancer, leaving his mother severely depressed in the final months of the pregnancy. The infant Saddam was sent to the family of his maternal uncle, Khairallah Talfah, until he was three.[3]

His mother remarried. Saddam gained three half-brothers as a result. His stepfather, Ibrahim al-Hassan, treated him harshly. At around ten, Saddam returned to Baghdad to live with his uncle, Kharaillah Tulfah. Tulfah, the father of Saddam's future wife, was a devout Sunni Muslim. Later in his life, relatives from his native Tikrit would become some of his closest advisors and supporters. According to Saddam, he learned many things from his uncle, a militant Iraqi nationalist. Under the guidance of his uncle, he attended a nationalistic secondary school in Baghdad. After secondary school, Saddam studied at Iraq's School of Law for three years. In 1957 at the age of 20 he left before completing his course to join the revolutionary pan-Arab Ba'ath Party, of which his uncle was a supporter. During this time, Saddam apparently supported himself as a secondary school teacher.[4]

Revolutionary sentiment was sweeping Iraq and much of the Middle East at this time. In Iraq, the stranglehold of the old elites (the conservative monarchists, established families, and merchants) was breaking down. The populist pan-Arab nationalism of Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt was also a profound influence on Saddam, whose ambitions were to be wider than Iraq itself. The rise of Nasser foreshadowed a wave of revolutions throughout the Middle East in the 1950s and 1960s, which would see the collapse of the monarchies of Iraq, Egypt, and Libya all of which had been established by the departing colonial powers. Nasser challenged the British and French, nationalized the Suez Canal, and strove to modernize Egypt and unite the Arab world politically.

In 1958, a year after Saddam had joined the Ba'ath party, army officers led by General Abdul Karim Qassim overthrew Faisal II of Iraq. The Ba'athists opposed the new government, and in 1959, Saddam was involved in the attempted United States-backed plot to assassinate Qassim.[5]

Rise to Power

Army officers with ties to the Ba'ath Party overthrew Qassim in a coup in 1963. Ba'athist leaders were appointed to the cabinet and Abdul Salam Arif became president. Arif dismissed and arrested the Ba'athist leaders later that year. Saddam returned to Iraq, but was imprisoned in 1964. Just prior to his imprisonment and until 1968, Saddam held the position of Ba'ath Party secretary. He escaped prison in 1967 and quickly became a leading member of the party. In 1968, Saddam participated in a bloodless coup led by Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr that overthrew Abdul Rahman Arif. Al-Bakr was named president and Saddam was deputy, and Deputy Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council. Saddam soon became the regime's most powerful player. According to biographers, Saddam never forgot the tensions within the first Ba'athist government, which formed the basis for his measures to promote Ba'ath party unity as well as his ruthless resolve to maintain power and programs to ensure social stability.

Soon after becoming deputy to the president, Saddam demanded and received the rank of four-star general despite his lack of military training.

Although Saddam was al-Bakr's deputy, he was a strong behind-the-scenes party politician whose strength was in organizing concealed opposition activity. He was adept at outmaneuveringÔÇöand at times ruthlessly eliminatingÔÇöpolitical opponents. Although al-Bakr was the older and more prestigious of the two, by 1969 Saddam Hussein clearly had become the moving force behind the party.

Modernization program

Saddam consolidated power in a nation riddled with profound tensions. Long before Saddam, Iraq had been split along social, ethnic, religious, and economic fault lines: Sunni versus Shi'ite; Arab versus Kurd; tribal chief versus urban merchant; and nomad versus peasant. Stable rule in a country rife with factionalism required the improvement of living standards. Saddam moved up the ranks in the new government by aiding attempts to strengthen and unify the Ba'ath party and taking a leading role in addressing the country's major domestic problems and expanding the party's following.

Saddam actively fostered the modernization of the Iraqi economy along with the creation of a strong security apparatus to prevent coups within the power structure and insurrections apart from it. Ever concerned with broadening his base of support among the diverse elements of Iraqi society and mobilizing mass support, he closely followed the administration of state welfare and development programs.

At the center of this strategy was Iraq's oil. On June 1, 1972, Saddam oversaw the seizure of international oil interests, which, at the time, had a monopoly on the country's oil. A year later, world oil prices rose dramatically as a result of the 1973 energy crisis, and skyrocketing revenues enabled Saddam to expand his agenda.

Within just a few years, Iraq was providing social services that were unprecedented among Middle Eastern countries. Saddam established and controlled the "National Campaign for the Eradication of Illiteracy" and the campaign for "Compulsory Free Education in Iraq," and largely under his auspices, the government established universal free schooling up to the highest education levels; hundreds of thousands learned to read in the years following the initiation of the program. The government also supported families of soldiers, granted free hospitalization to everyone, and gave subsidies to farmers. Iraq created one of the most modernized public-health systems in the Middle East, earning Saddam an award from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). [6] [7]

To diversify the largely oil-based economy, Saddam implemented a national infrastructure campaign that made great progress in building roads, promoting mining, and developing other industries. The campaign revolutionized Iraq's energy industries. Electricity was brought to nearly every city in Iraq, and many outlying areas.

Before the 1970s, most of Iraq's people lived in the countryside, where Saddam himself was born and raised, and roughly two-thirds were peasants. This number decreased quickly during the 1970s as the country invested much of its oil profits into industrial expansion.

Nevertheless, Saddam focused on fostering loyalty to the Ba'athist government in the rural areas. After nationalizing foreign oil interests, Saddam supervised the modernization of the countryside, mechanizing agriculture on a large scale, and distributing land to peasant farmers.[8] The Ba'athists established farm cooperatives, in which profits were distributed according to the labors of the individual and the unskilled were trained. The government's commitment to agrarian reform was demonstrated by the doubling of expenditures for agricultural development in 1974-1975. Agrarian reform in Iraq did improve the living standard of the peasantry and increased production, though not to the levels Saddam had hoped for.

Saddam became personally associated with Ba'athist welfare and economic development programs in the eyes of many Iraqis, widening his appeal both within his traditional base and among new sectors of the population. These programs were part of a combination of "carrot and stick" tactics to enhance support in the working class, the peasantry, and within the party and the government bureaucracy.

Saddam's organizational prowess was credited with Iraq's rapid pace of development in the 1970s; development went forward at such a fevered pitch that two million persons from other Arab countries and Yugoslavia worked in Iraq to meet the growing demand for labor.

The Presidency

In 1979 al-Bakr started to make treaties with Syria, also under Ba'athist leadership, that would lead to unification between the two countries. Syrian President Hafez al-Assad would become deputy leader in a union, and this would drive Saddam to obscurity. Saddam acted to secure his grip on power. He forced the ailing al-Bakr to resign on July 16, 1979, and formally assumed the presidency.

Shortly afterwards, he convened an assembly of Ba'ath party leaders on July 22, 1979. During the assembly, which he ordered videotaped, Saddam claimed to have found spies and conspirators within the Ba'ath Party and read out the names of 68 members that he alleged to be such fifth columnists. These members were labeled "disloyal" and were removed from the room one by one and taken into custody. After the list was read, Saddam congratulated those still seated in the room for their past and future loyalty. The 68 people arrested at the meeting were subsequently put on trial, and 22 were sentenced to execution for treason.

Saddam Hussein as a secular ruler

Saddam saw himself as a social revolutionary and a modernizer, following the Nasser model. To the consternation of Islamic conservatives, his government gave women added freedoms and offered them high-level government and industry jobs. Saddam also created a Western-style legal system, making Iraq the only country in the Persian Gulf region not ruled according to traditional Islamic law (Sharia). Saddam abolished the Sharia law courts, except for personal injury claims.

Domestic conflict impeded Saddam's modernizing projects. Iraqi society is divided along lines of language, religion and ethnicity; Saddam's government rested on the support of the 20% minority of largely working class, peasant, and lower middle class Sunnis, continuing a pattern that dates back at least to the British Mandate authority's reliance on them as administrators.

The Shi'a majority were long a source of opposition to the government's secular policies, and the Ba'ath Party was increasingly concerned about potential Shi'a Islamist influence following the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The Kurds of northern Iraq (who are Sunni Muslims but not Arabs) were also permanently hostile to the Ba'athist party's pan-Arabism. To maintain his regime Saddam tended either to provide them with benefits so as to co-opt them into the regime, or to take repressive measures against them. The major instruments for accomplishing this control were the paramilitary and police organizations. Beginning in 1974, Taha Yassin Ramadan, a close associate of Saddam, commanded the People's Army, which was responsible for internal security. As the Ba'ath Party's paramilitary, the People's Army acted as a counterweight against any coup attempts by the regular armed forces. In addition to the People's Army, the Department of General Intelligence (Mukhabarat) was the most notorious arm of the state security system, feared for its use of torture and assassination. It was commanded by Barzan Ibrahim al-Tikriti, Saddam's younger half-brother. Since 1982, foreign observers believed that this department operated both at home and abroad in their mission to seek out and eliminate Saddam's perceived opponents.

Saddam justified Iraqi nationalism by claiming a unique role of Iraq in the history of the Arab world. As president, Saddam made frequent references to the Abbasid period, when Baghdad was the political, cultural, and economic capital of the Arab world. He also promoted Iraq's pre-Islamic role as Mesopotamia, the ancient cradle of civilization, alluding to such historical figures as Nebuchadrezzar II and Hammurabi. He devoted resources to archaeological explorations. In effect, Saddam sought to combine pan-Arabism and Iraqi nationalism, by promoting the vision of an Arab world united and led by Iraq.

As a sign of his consolidation of power, Saddam's personality cult pervaded Iraqi society. Thousands of portraits, posters, statues and murals were erected in his honor all over Iraq. His face could be seen on the sides of office buildings, schools, airports, and shops, as well as on Iraqi currency. Saddam's personality cult reflected his efforts to appeal to the various elements in Iraqi society. He appeared in the costumes of the Bedouin, the traditional clothes of the Iraqi peasant (which he essentially wore during his childhood), and even Kurdish clothing, but also appeared in Western suits, projecting the image of an urbane and modern leader. Sometimes he would also be portrayed as a devout Muslim, wearing full headdress and robe, praying toward Mecca.

Foreign Affairs

In foreign affairs, Saddam sought to have Iraq play a leading role in the Middle East. Iraq signed an aid pact with the Soviet Union in 1972, and arms were sent along with several thousand advisers, making Iraq one of the main Soviet allies in the Middle East. However, the 1978 executions of Iraqi Communists, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Soviet hope for increased influence in Iran and a shift of trade toward the West strained Iraqi relations with the Soviet Union, leading to a more Western orientation from then until the Gulf War in 1991.

After the oil crisis of 1973 France had changed to a more pro-Arab policy and was accordingly rewarded by Saddam with closer ties. He made a state visit to France in 1976, cementing close ties with some French business and conservative political circles. Saddam led Arab opposition to the 1979 Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel. In 1975 he negotiated an accord with Iran that contained Iraqi concessions on border disputes. In return, Iran agreed to stop supporting opposition Kurds in Iraq.

Saddam initiated Iraq's nuclear enrichment project in the 1980s, with French assistance. The first Iraqi nuclear reactor was named by the French "Osirak," a portmanteau formed from "Osiris," the name of the French experimental reactor that served as template and "Irak," the French spelling of "Iraq." Osirak was destroyed on June 7, 1981[9] by an Israeli air strike (Operation Opera), because Israel suspected it was going to start producing weapons-grade nuclear material.

At the founding as a modern state in 1920, Churchill had recommended making the Kurds in the northern part of the country independent to protect them from oppression from Baghdad. Iraq had been carved from out of the former Ottoman Empire by the British and French at the end of World War I then mandated to Britain by the League of Nations. Saddam did negotiate an agreement in 1970 with separatist Kurdish leaders, giving them autonomy, but the agreement broke down. The result was brutal fighting between the government and Kurdish groups and even Iraqi bombing of Kurdish villages in Iran, which caused Iraqi relations with Iran to deteriorate. After Saddam had negotiated the 1975 treaty with Iran, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi withdrew support for the Kurds, who suffered a total defeat and a campaign in which 200,000 Kurds were deported followed.

The Iran-Iraq War (1980ÔÇô1988)

In 1979 Iran's Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was overthrown in the Islamic Revolution, thus giving way to an Islamic republic led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The influence of revolutionary Shi'ite Islam grew apace in the region, particularly in countries with large Shi'ite populations, especially Iraq. Saddam feared that radical Islamic ideasÔÇöhostile to his secular ruleÔÇöwere rapidly spreading in southern Iraq among the majority Shi'ite population.

There had also been bitter enmity between Saddam and Khomeini since the 1970s. Khomeini, having been exiled from Iran in 1964, took up residence in Iraq, at the Shi'ite holy city of An Najaf. There he involved himself with Iraqi Shi'ites and developed a strong, worldwide religious and political following. Under pressure from the Shah, who had agreed to a rapprochement between Iraq and Iran in 1975, Saddam agreed to expel Khomeini in 1978.

After Khomeini gained power, skirmishes between Iraq and revolutionary Iran occurred for ten months over the sovereignty of the disputed Arvandrud/Shatt al-Arab waterway, which divides the two countries. During this period, Saddam Hussein continually maintained that it was in Iraq's interest not to engage with Iran, and that it was in the interests of both nations to maintain peaceful relations. However, in a private meeting with Salah Omar Al-Ali, Iraq's permanent ambassador to the United Nations, he revealed that he intended to invade and occupy a large part of Iran within months. Iraq invaded Iran, first attacking Mehrabad Airport of Tehran and then entering the oil-rich Iranian land of Khuzestan, which also has a sizeable Arab minority, on September 22, 1980 and declared it a new province of Iraq. United States policy was to support neither side and discourage other countries from doing so during this time.[10]

In the first days of the war, there was heavy ground fighting around strategic ports as Iraq launched an attack on Khuzestan. After making some initial gains, Iraq's troops began to suffer losses from human wave attacks by Iran. By 1982, Iraq was on the defensive and looking for ways to end the war. At this point, Saddam asked his ministers for candid advice. Health Minister Riyadh Ibrahim suggested that Saddam temporarily step down to promote peace negotiations. IbrahimÔÇÖs chopped up body was delivered to his wife the next day.[11]

Iraq quickly found itself bogged down in one of the longest and most destructive wars of attrition of the twentieth century. During the war, Iraq used chemical weapons against Iranian forces fighting on the southern front and Kurdish separatists who were attempting to open up a northern front in Iraq with the help of Iran. These chemical weapons were developed by Iraq from materials and technology supplied primarily by West German companies.[12]

Saddam reached out to other Arab governments for cash and political support during the war, particularly after Iraq's oil industry severely suffered at the hands of the Iranian navy in the Persian Gulf. Iraq successfully gained some military and financial aid, as well as diplomatic and moral support, from the Soviet Union, China, France, and the United States, which together feared the prospects of the expansion of revolutionary Iran's influence in the region. The Iranians, claiming that the international community should force Iraq to pay war reparations to Iran, refused any suggestions for a cease-fire. They continued the war until 1988, hoping to bring down Saddam's secular regime and instigate a Shi'ite rebellion in Iraq.

On March 16 1988, the Kurdish town of Halabja was attacked with a mix of mustard gas and nerve agents, killing 5,000 civilians, and maiming, disfiguring, or seriously debilitating 10,000 more. [13] The attack occurred in conjunction with the 1988 al-Anfal campaign designed to reassert central control of the mostly Kurdish population of areas of northern Iraq and defeat the Kurdish peshmerga rebel forces. The United States now maintains that Saddam ordered the attack to terrorize the Kurdish population in northern Iraq, but Saddam's regime claimed at the time that Iran was responsible for the attack[14] and US analysts did not definitively reject the claim until several years later.

The bloody eight-year war ended in a stalemate. There were hundreds of thousands of casualties, perhaps upwards of 1.7 million died on both sides. Both economies, previously healthy and expanding, were left in ruins.

Saddam borrowed very large sums of money from other Arab states during the 1980s to fight Iran and was stuck with a war debt of roughly $75 billion. Faced with rebuilding Iraq's infrastructure, Saddam desperately sought out cash once again, this time for postwar reconstruction. The desperate search for foreign credit would eventually humiliate the strongman who had long sought to dominate Arab nationalism throughout the Middle East.

Tensions with Kuwait

The end of the war with Iran served to deepen latent tensions between Iraq and its wealthy neighbor Kuwait. Saddam saw his war with Iran as having spared Kuwait from the imminent threat of Iranian domination. Since the struggle with Iran had been fought for the benefit of the other Gulf Arab states as much as for Iraq, he argued, a share of Iraqi debt should be forgiven. Saddam urged the Kuwaitis to forgive the Iraqi debt accumulated in the war, some $30 billion, but the Kuwaitis refused, claiming that Saddam was responsible to pay off his debts for the war he started.

To raise money for postwar reconstruction, Saddam pushed oil-exporting countries to raise oil prices by cutting back oil production. Kuwait refused to cut production and spearheaded the opposition in OPEC to the cuts that Saddam had requested. Kuwait was pumping large amounts of oil, and thus keeping prices low, when Iraq needed to sell high-priced oil from its wells to pay off its huge debt.

Saddam also showed disdain for the Kuwait-Iraq boundary line. One of the few articles of faith uniting the political scene in a nation rife with sharp social, ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic divides was the belief that Kuwait had no right to even exist in the first place. For at least half a century, Iraqi nationalists had espoused the belief that Kuwait was historically an integral part of Iraq, and that Kuwait had only come into being through the maneuverings of British imperialism.

The colossal extent of Kuwaiti oil reserves intensified tensions in the region. Kuwait's reserves (with a population of a mere 2 million next to Iraq's 25) were roughly equal to those of Iraq. Taken together, Iraq and Kuwait sat on top of some 20% of the world's known oil reserves; Saudi Arabia, by comparison, holds 25%.

Saddam further alleged that the Kuwait slant drilled oil out of wells that Iraq considered to be within its disputed border with Kuwait. Given that at the time Iraq was not regarded as a pariah state, Saddam was able to complain about the alleged slant drilling to the U.S. State Department. Although this had continued for years, Saddam now needed oil money to stem a looming economic crisis. Saddam still had an experienced and well-equipped army, which he used to influence regional affairs. He ordered troops to the Iraq-Kuwait border.

As Iraq-Kuwait relations rapidly deteriorated, Saddam was receiving conflicting information about how the U.S. would respond to the prospects of an invasion. Washington had been trying to cultivate a more constructive relationship with Iraq for roughly a decade and had sent billions of dollars to Saddam to keep him from forming a strong alliance with the Soviets. [15]

U.S. ambassador to Iraq April Glaspie met with Saddam in an emergency meeting on July 25, 1990, where the Iraqi leader stated his intention to continue talks. U.S. officials attempted to maintain a conciliatory line with Iraq, indicating that while President Bush and Secretary of State James Baker did not want force used, they would not take any position on the Iraq-Kuwait boundary dispute and did not want to become involved. The transcript, however, does not show any statement of approval of, acceptance of, or foreknowledge of the invasion. Later, Iraq and Kuwait met for a final negotiation session, which failed. Saddam then sent his troops into Kuwait.

The Gulf War

On August 2, 1990, Saddam invaded and annexed the emirate of Kuwait. U.S. President George H. W. Bush responded cautiously for the first several days after the invasion. On the one hand, Iraq, prior to this point, had been a virulent enemy of Israel and was allied with the Soviet Union implying that they might support him.[16] On the other hand Kuwait was considered an ally. U.S. interests were heavily invested in the region, and the invasion triggered fears that the price of oil, and therefore the world economy, was at stake.[17] The United Kingdom was also concerned. Britain had a close historical relationship with Kuwait, dating back to British colonialism in the region, and also benefited from billions of dollars in Kuwaiti investment. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher underscored the risk the invasion posed to Western interests to Bush in an in-person meeting one day after the invasion, telling him, ÔÇťDon't go wobbly on me, George.ÔÇŁ[18]

Cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union made possible the passage of resolutions in the United Nations Security Council giving Iraq a deadline to leave Kuwait and approving the use of force if Saddam did not comply with the timetable. U.S. officials feared that Iraq would retaliate against oil-rich Saudi Arabia, a close ally of Washington since the 1940s, for the Saudis' opposition to the invasion of Kuwait. Accordingly, the U.S. and a group of allies, including countries as diverse as Egypt, Syria and Czechoslovakia, deployed massive amounts of troops along the Saudi border with Kuwait and Iraq in order to deter the Iraqi army, the largest in the Middle East.

During the period of negotiations and threats following the invasion, Saddam raised the subject of the Palestinian problem by promising to withdraw his forces from Kuwait if Israel would relinquish the occupied territories in the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and the Gaza Strip. Saddam's proposal further split the Arab world, pitting U.S. and Western-supported Arab states against the Palestinians. The allies ultimately rejected any connection between the Kuwait crisis and Palestinian issues.

Saddam ignored the Security Council deadline. With the unanimous consent of the Security Council, a U.S. led coalition launched round-the-clock missile and aerial attacks on Iraq, beginning January 16, 1991. Israel, though subjected to attack by Iraqi missiles, refrained from retaliating in order not to provoke Arab states into leaving the coalition. A ground force comprised largely of U.S. and British armored and infantry divisions ejected Saddam's army from Kuwait in February 1991 and occupied the southern portion of Iraq as far as the Euphrates. Before leaving, Saddam ordered Kuwaiti oil fields set ablaze.

The over-manned and ill-equipped Iraqi army proved unable to compete on the battlefield with the highly mobile coalition land forces and their overpowering air support. 175,000 Iraqis were taken prisoner and casualties were estimated at approximately 20,000 according to U.S. data, with other sources pinning the number as high as 100,000. As part of the cease-fire agreement, Iraq agreed to abandon all chemical and biological weapons and allow UN observers to inspect the sites. UN trade sanctions would remain in effect until Iraq complied with all terms.

In the aftermath of the fighting, social and ethnic unrest among Shi'a Muslims, Kurds, and dissident military units threatened the stability of Saddam's government. Uprisings began in the Kurdish north and Shi'a southern and central parts of Iraq, but were quelled in short order. In 2005 the BBC reported that as many as 30,000 were killed during those 1991 rebellions.[19]

The United States, after urging the Iraqi people to rise up and overthrow Saddam, did nothing to assist those who did. Further playing into the plans of Saddam, the US unwittingly loosened rules on helicopter flights in the no-fly zones allowing Saddam's remaining military force to easily put down the rebellions. U.S. ally Turkey opposed any prospect of Kurdish independence, and the Saudis and other conservative Arab states feared an Iran-style Shi'a revolution. Saddam, having survived the immediate crisis in the wake of defeat and a car crash, which left a small scar in his face and an injury on a finger, according to his now defected personal doctor, was left firmly in control of Iraq, although the country never recovered either economically or militarily from the Persian Gulf War. Saddam routinely trumpeted the survival of his regime as ÔÇťproofÔÇŁ the Iraq had won the war against America. This message earned Saddam a great deal of popularity in many sectors of the Arab world.

Saddam increasingly portrayed himself as a devout Muslim, in an effort to co-opt the conservative religious segments of society. Elements of Sharia law were re-introduced, such as the 2001 edict imposing the executions for sodomy, rape, and prostitution, the legalization of honor killings, and the ritual phrase Allahu Akbar (God is greatest), was added to the Iraq national flag in Saddam Hussein's handwriting.

1991ÔÇô2003

Relations between the United States and Iraq remained tense following the Gulf War. In April 1993, the Iraqi Intelligence Service allegedly attempted to assassinate former President George H. W. Bush during a visit to Kuwait. Kuwaiti security forces apprehended a group of Iraqis at the scene of an alleged bombing attempt. With Bill Clinton in the White House, on June 26, 1993, the U.S. launched a missile attack targeting Baghdad intelligence headquarters in retaliation for the alleged attempt to attack former President Bush.[20] [21]

The UN sanctions placed upon Iraq when it invaded Kuwait were not lifted, blocking Iraqi oil exports. This caused immense hardship in Iraq and virtually destroyed the Iraqi economy and state infrastructure. Only smuggling across the Syrian border and humanitarian aid (the UN Oil-for-Food Programme) ameliorated the humanitarian crisis. Limited amounts of income from the United Nations started flowing into Iraq through the UN Oil-for-Food Programme.

U.S. officials continued to accuse Saddam Hussein of violating the terms of the Gulf War's cease fire, by developing weapons of mass destruction and other banned weaponry, refusing to give out adequate information on these weapons, and violating the UN-imposed sanctions and no-fly zones. Isolated military strikes by U.S. and British forces continued on Iraq sporadically, the largest being Operation Desert Fox in 1998. Charges of Iraqi impediment to UN inspection of sites thought to contain illegal weapons were claimed as the reasons for crises between 1997 and 1998, culminating in intensive U.S. and British missile strikes on Iraq, December 16-19, 1998. After two years of intermittent activity, U.S. and British warplanes struck harder at sites near Baghdad in February, 2001.

Saddam's support base of Tikriti tribesmen, family members, and other supporters were divided after the war. In the following years, this contributed to the government's increasingly repressive and arbitrary nature. Domestic repression inside Iraq grew worse, and Saddam's sons, Uday Hussein and Qusay Hussein, became increasingly powerful and carried out a private reign of terror. They likely had a leading hand when, in August 1995, two of Saddam Hussein's sons-in-law (Hussein Kamel and Saddam Kamel), who held high positions in the Iraqi military, defected to Jordan. Both were killed after returning to Iraq the following February.

Iraqi cooperation with UN weapons inspection teams was questioned on several occasions during the 1990s and UNSCOM chief weapons inspector Richard Butler withdrew his team from Iraq in November 1998 citing Iraqi non-cooperation, without the permission of the UN, although a UN spokesman subsequently stated that "the bulk of" the Security Council supported the move.[22] Iraq accused Butler and other UNSCOM officials of acting as spies for the United States. This was supported by reports in the Washington Post and the Boston Globe, citing anonymous sources, which said that Butler had known of and co-operated with a US electronic eavesdropping operation that allowed intelligence agents to monitor military communications in Iraq. After a crisis ensued and the U.S. contemplated military action against Iraq, Saddam resumed cooperation.[23] The inspectors returned, but were withdrawn again on 16 December [24]. Butler had given a report the UN Security Council on 15 December in which he expressed dissatisfaction with the level of compliance. Three out of five of the Permanent Members of the U.N. Security Council subsequently objected to Butler's withdrawal. Butler reported in his biography that U.S. Ambassador Peter Burleigh, acting on instructions from Washington, suggested he pull his team from Iraq in order to protect them from the forthcoming U.S. and British airstrikes.

Saddam continued to loom large in American consciousness as a major threat to Western allies such as Israel and oil-rich Saudi Arabia, to Western oil supplies from the Gulf States, and to Middle East stability generally. U.S. President Bill Clinton maintained economic sanctions, as well as air patrols in the "Iraqi no-fly zones." In October 1998, President Clinton signed the Iraq Liberation Act.[25] The act called for "regime change" in Iraq and authorizes the funding of opposition groups. Following the issuance of a UN report detailing Iraq's failure to cooperate with inspections, Clinton authorized Operation Desert Fox, a three-day air-strike to hamper Saddam's weapons-production facilities and hit sites related to weapons of mass destruction.

Several journalists have reported on Saddam's ties to anti-Israeli and Islamic terrorism prior to 2000. Saddam was also known to have had contacts with Palestinian terrorist groups. Early in 2002, Saddam told Faroq al-Kaddoumi, head of the Palestinian political office, he would raise the sum granted to each family of Palestinians who die as suicide bombers in the uprising against Israel to US$25,000 instead of US$10,000.[26][27] Some news reports detailed links to terrorists, including Carlos the Jackal, Abu Nidal, Abu Abbas and Osama bin Laden.[28] However, no conclusive evidence of any kind, linking Saddam and bin Laden's al-Qaeda organization has ever been produced by any US government official. It is the official assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community that contacts between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda over the years did not lead to a collaborative relationship. The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence was able to find evidence of only one such meeting, as well as evidence of two occasions "not reported prior to the war, in which Saddam Hussein rebuffed meeting requests from an al-Qa'eda operative. The Intelligence Community has found no other evidence of meetings between al-Qa'eda and Iraq." The Senate Committee concluded that while there was no evidence of any Iraqi support of al-Qaeda, there was convincing evidence of hostility between the two entities.

2003 invasion of Iraq

The U.S. political atmosphere following the September 11, 2001 attacks, bolstering the influence of the neo-conservative faction in the White House, on Capitol Hill and throughout the Washington landscape. In his January 2002 State of the Union message to Congress, U.S. president George Bush raised the spectre of an ÔÇťaxis of evilÔÇŁ comprising Iran, North Korea, and Iraq, further charging the Iraqi regime with plotting to ÔÇťdevelop anthrax, and nerve gas, and nuclear weapons for over a decade,ÔÇŁ and continuing to ÔÇťflaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror.ÔÇŁ The United Nations Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1441 on November 8, 2002. The resolution urged Iraq to disarm or face "serious consequences."

As the prospect of war loomed, on February 24, 2003, Saddam gave an interview to CBS News anchor Dan RatherÔÇöhis first interview with a U.S. reporter in more than a decade.[29] CBS aired the taped three-hour interview on February 26.

With the intent to avoid an all out war, the United States made at least two attempts to kill Saddam using targeted air strikes with smart bombs; however, the strikes were based on faulty intelligence. Saddam appeared on television the next day, confirming that he was still alive. This notwithstanding, Iraqi military and government completely collapsed within three weeks of the March 20 beginning of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and by early April, Coalition forces led by the United States occupied much of Iraq. With resistance to invading forces largely neutralized, it was apparent Saddam's control over Iraq was lost. When Baghdad fell to the coalition forces on April 9, he was still seen in videos purportedly in the Baghdad suburbs surrounded by supporters.

Escape and capture

Escape

As the US forces were occupying the Republican Palace and other central landmarks and ministries on April 9, Saddam Hussein emerged from his command bunker beneath the Al A'Zamiyah district of northern Baghdad and greeted excited members of the local public. In the BBC Panorama programme Saddam on the Run witnesses were found for these and other later events. The walkabout was captured on film and broadcast several days after the event on Al-Arabiya Television and was also witnessed by ordinary people who corroborated the date afterwards. He was accompanied by bodyguards and other loyal supporters including at least one of his sons and his personal secretary.

After the walkabout, Saddam returned to his bunker and made preparations for his family. According to his eldest daughter Raghad Hussein he was, by this point, aware of the "betrayal" of a number of key figures involved in the defense of Baghdad. There was a lot of confusion between Iraqi commanders in different sectors of the capital and communication between them and Saddam and between Saddam and his family were becoming increasingly difficult. This version of events is supported by Muhammad Saeed al-Sahhaf, the former Information Minister who struggled to know what was happening after the US captured Baghdad International Airport.

The Americans had meanwhile started receiving rumours that Saddam was in Al A'Zamiyah and at dawn on April 10 they dispatched three companies of US Marines to capture or kill him. As the Americans closed in, and realising that Baghdad was lost, Saddam arranged for cars to collect his eldest daughters, Raghad and Rana, and drive them to Syria. His wife Sajida Talfah and youngest daughter Hala had already left Iraq several weeks prior. Raghad Hussein stated in an interview for Panorama:

After about midday my Dad sent cars from his private collection for us. We were told to get in. We had almost lost contact with my father and brothers because things had got out of hand. I saw with my own eyes the [Iraqi] army withdrawing and the terrified faces of the Iraqi soldiers who, unfortunately, were running away and looking around them. Missiles were falling on my left and my right - they were not more than fifty or one hundred meters away. We moved in small cars. I had a gun between my feet just in case. Attributed to Raghad Hussein

Then according to the testimony of a former bodyguard Saddam Hussein dismissed almost his entire staff:

The last time I saw him he said: My sons, each of you go to your homes. We said: Sir, we want to stay with you. Why should we go? But he insisted. Even his son, Qusay, was crying a little. He [Saddam] was trying not to show his feelings. He was stressed but he didn't want to destroy the morale of the people who were watching him, but inside, he was definitely broken. Attributed to an anonymous former bodyguard

After this he changed out of his uniform and with only two bodyguards to guard him, left Baghdad in a plain white Oldsmobile and made his way to a specially prepared bunker in Dialah on the northern outskirts of the city.

Ayad Allawi in interview stated that Saddam stayed in the Dialah bunker for three weeks as Baghdad and the rest of Iraq were occupied by US forces. Initially he and his entourage used satellite telephones to communicate with each other. As this became more risky they resorted to sending couriers with written messages. One of these couriers was reported to have been his own nephew. However, their cover was given away when one of the couriers was captured and Saddam was forced to evacuate the Dialah bunker and resorted to changing location every few hours. There were numerous sightings of him in Beiji, Baquba and Tikrit to the north of Baghdad over the next few months as he shuttled between safe houses disguised as a shepherd in a plain taxi. How close he came to being captured during this period may never be made public. Sometime in the middle of May he moved to the countryside around his home town of Tikrit.

A series of audio tapes claiming to be from Saddam were released at various times, although the authenticity of these tapes remains uncertain.

Saddam Hussein was at the top of the United States list of most-wanted Iraqis, and many of the other leaders of the Iraqi government were arrested, but extensive efforts to find him had little effect. In June in a joint raid by special operations forces and the 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment of 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, the former president's personal secretary Abid Hamid Mahmud, Ace of Diamonds and number 4 after Saddam and his sons Uday and Qusay, was captured. Documents discovered with him enabled intelligence officers to work out who was who in Saddam's circle. Manhunts were launched nightly throughout the Sunni triangle. Safe houses and family homes were raided as soon as any tip came in that someone in Saddam's circle might be in the area.

In July 2003 in an engagement with U.S. forces after a tip-off from an Iraqi informant Saddam's sons were cornered in a house in Mosul and shot to death in a firefight.

According to one of Saddam's bodyguards, the former president actually went to the grave himself on the evening of the funeral:

After the funeral people saw Saddam Hussein visiting the graves with a group of his protectors. No one recognized them and even the car they came in wasn't spotted. At the grave Saddam read a verse from the Koran and cried. There were flags on the grave. After he finished reading, he took the flags and left. He cried for his sons. Anonymous reporter

This story, however, likely resulted to explain the missing flags. The commander of the 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment in Tikrit and Auja, where the sons were buried, had the cemetery heavily guarded. The flags were removed by United States forces to prevent his sons being honored as martyrs. These flags now reside at the US National Infantry Museum at Fort Benning, Georgia.

The raids and arrests of people known to be close to the former President drove him deeper underground. Once more the trail was growing colder. In August the US military released photofits of how Saddam might be disguising himself in traditional garb, even without his signature mustache. By the early autumn the Pentagon had also formed a secret unit ÔÇô Taskforce 121. Using electronic surveillance and undercover agents, the CIA and Special Forces scoured Iraq for clues.

By the beginning of November, 2005 Saddam was under siege. His home town and powerbase were surrounded and his faithful bodyguards targeted and then arrested one by one by the Americans. Protests erupted in several towns in the Sunni triangle. Meanwhile some Sunni Muslims showed their support for Saddam.

On December 12 Mohamed Ibrahim Omar al-Musslit was unexpectedly captured in Baghdad. Mohamed had been a key figure in the President's special security organization. His cousin Adnan had been captured in July by the 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment in Tikrit. It appeared that Mohamed had taken control of Saddam on the run, the only person who knew where he was from hour to hour and who was with him. According to US sources it took just a few hours of interrogation for him to crack and betray Saddam.

Within hours Colonel James Hickey (1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division) together with US Special Operations Forces launched Operation Red Dawn and under cover of darkness made for the village of Ad-Dawr on the outskirts of Tikrit. The informer had told US forces the former president would be in one of two groups of buildings on a farm codenamed Wolverine 1 and Wolverine 2.

Capture

On December 13, 2003, citing Kurdish leader Jalal Talabani, the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) of Iran was first to report the apprehension and arrest of Saddam Hussein. These reports were soon confirmed by other members of the Iraq Interim Governing Council, U.S. military sources, and by British prime minister Tony Blair. In a Baghdad press conference with the U.S. civil administrator in Iraq, Paul Bremer, Saddam's capture was formally announced, leading with, "Ladies and gentlemen, we got him!" Bremer went on to report the time as approximately 8:30 P.M. local (23:30 UTC), on December 13, in an underground "spider hole" at a farmhouse in ad-Dawr near his home town Tikrit, in what was called Operation Red Dawn.[30]

During his arrest, Saddam reportedly declared, "I am the President of Iraq," to which an American soldier is said to have replied, "President Bush sends his regards." [31]

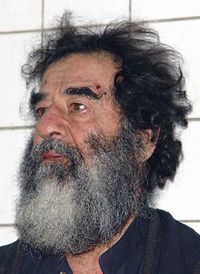

The video footage presented by Bremer showed Hussein in full beard with longer than usual, disheveled hair. He was described as being in good health, "talkative and co-operative." DNA testing was used to further confirm the captive's identity. Members of the Governing Council visiting with Hussein following his capture reported him as unrepentant and believing of himself as having been a "firm, but just ruler." It later emerged that the information leading to his capture was obtained from a detainee under interrogation.

Incarceration

According to US military sources, immediately following Saddam's December 13th capture, he was hooded, his hands bound and he was taken by a military HMMWV vehicle to an awaiting helicopter and flown to the US base adjacent to one of his former palaces in Tikrit. He was then loaded onto again to a helicopter and flown to the main US base at Baghdad International Airport where he was transferred to the Camp Cropper facility. He was then officially photographed and received medical attention and was groomed. The following day he was visited in his cell by members of the Iraqi Governing Council with Ahmed Chalabi and Adnan Pachachi among them. It is believed he remained there in high security during most of the time of his detention. Details of his interrogations are unknown.

After Saddam's death, reports emerged from the nurse charged with his care at Camp Cropper from 2004 until 2005. US Army Master Sergeant Robert Ellis, told his home town newspaper the St Louis Post-Dispatch that Saddam was held in a 1.8m x 2.4m (6 ft x 8 ft) cell furnished with a cot, table, two plastic chairs and two wash basins. When he was allowed to go outside, Hussein saved bread crumbs from his meals to feed the birds, he watered the weeds in a jail garden and had coffee with his cigars for his blood pressure.[32] Ellis also said of Hussein, "When he was with me, he was in a different environment. I posed no threat. In fact, I was there to help him, and he respected that."

Trial

Held in custody by U.S. forces at Camp Cropper in Baghdad, on June 30, 2004, Saddam Hussein and 11 senior Ba'athist officials were handed over legally (though not physically) to the interim Iraqi government to stand trial for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. A few weeks later, he was charged by the Special Tribunal with crimes committed against the inhabitants of Dujail in 1982, following a failed assassination attempt against him. Specific charges included the murder of 148 people, torture of women and children and the illegal arrest of 399 others.[33] Among the many challenges of the trial were:

- Hussein and his lawyersÔÇÖ contesting the court's authority and maintaining that he was yet the President of Iraq.[34]

- The assassinations and attempts on the lives of several of Hussein's lawyers.

- Midway through the trial, the chief presiding judge was replaced after accusations of bias were leveled.

On November 5, 2006, Saddam Hussein was found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to death by hanging. Hussein's half brother, Barzan Ibrahim, and Awad Hamed al-Bandar, head of Iraq's Revolutionary Court in 1982, were convicted of similar charges as well. Verdict and sentencing were both appealed but subsequently affirmed by Iraq's Supreme Court of Appeals. The sentence was carried out 25 days later with Hussein being executed by hanging on December 30, 2006.

Execution

Saddam was hanged on the first day of Eid ul-Adha, December 30, 2006 at approximately 6:00 A.M. local time (03:00 UTC). The execution was carried out at "Camp Justice," an Iraqi army base in Kadhimiya, a neighborhood of northeast Baghdad. Camp Justice was previously used by Saddam as his military intelligence headquarters, then known as Camp Banzai, where Iraqi civilians were taken to be tortured and executed on the same gallows where Saddam was hanged. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki launched an investigation to determine who leaked a video recorded on the mobile telephone of a witness to the execution in which he was taunted moments before his death.

Saddam was buried at his birthplace of Al-Awja in Tikrit, Iraq, 3 km (2 mi) from his sons Uday and Qusay Hussein, on December 31, 2006, at 4:00 A.M. local time (01:00 UTC).[35]

Government positions held by Saddam Hussein

- Head of Security (Iraqi Intelligence Service), 1963

- Vice President of the Republic of Iraq, 1968 ÔÇô 1979

- President of the Republic of Iraq, 1979 ÔÇô 2003

- Prime Minister of the Republic of Iraq, (various non-continuous dates)

- Head of the Revolutionary Command Council, 1979 ÔÇô 2003

Marriage and family relationships

Saddam married his cousin Sajida Talfah in 1963. Sajida is the daughter of Khairallah Talfah, Hussein's uncle and mentor. Their marriage was arranged for Hussein at age five when Sajida was seven; however, the two never met until their wedding in Egypt during his exile. Together they had two sons, Uday and Qusay, and three daughters, Rana, Raghad and Hala. Uday controlled the media, and was named "Journalist of the Century" by the Iraqi Union of Journalists. Qusay ran the elite Republican Guard, and was considered Heir Presumptive. Both brothers are said to have made fortunes for themselves smuggling oil. Sajida, Raghad, and Rana were all placed under house arrest due to suspicions of their involvement in Uday's assassination attempt on December 12, 1996. General Adnan Khairallah Tuffah, Sajida's brother and childhood friend of Hussein, was allegedly executed due to his growing popularity. Hussein's two sons Uday and Qusay were both killed in a violent six-hour gun battle against U.S. forces on July 22, 2003. Still photos of their badly shot-up bodies were taken and widely distributed ÔÇťin an effort to convince any skeptical Iraqis that Uday, 39, and Qusay, 37, are really dead.ÔÇŁ[36] His grandson Mustapha was the last one to die.

Hussein also married two other women: Samira Shahbandar (rumored to have been his favorite), whom he married in 1986 after forcing her husband to divorce her[37], and Nidal al-Hamdani, the general manager of the Solar Energy Research Center in the Council of Scientific Research, whose husband was also persuaded to divorce his wife.[38] There have apparently been no political issues from these latter two marriages. Hussein's third son, Ali, is from Samira.

In August 1995, Rana and her husband Hussein Kamel al-Majid and Raghad and her husband, Saddam Kamel al-Majid, defected to Jordan, taking their children with them. They returned to Iraq when they received assurances that Saddam would pardon them. Within three days of their return in February 1996, both of the Majid brothers were attacked and killed in a gunfight with other clan members who considered them traitors. Saddam had made it clear that although pardoned, they would lose all status and would not receive any protection.

Hussein's daughter Hala is married to Jamal Mustafa Sultan al-Tikriti, the deputy head of Iraq's Tribal Affairs Office. Neither has been known to be involved in politics. Jamal surrendered to U.S. troops in April 2003. Another cousin, Ali Hassan al-Majid, infamously known as ÔÇťChemical Ali,ÔÇŁ was accused of ordering the use of poison gas in 1988, and is now in U.S. custody.

See also

Notes

- ÔćĹ Saddam, pronounced [s╦ü╔Ĺd'd├Ž╦Ém], is his personal name, means the stubborn one or he who confronts in Arabic (in Iraq also a term for a car's bumper). Hussein (Sometimes also transliterated as Hussayn or Hussain) is not a surname in the Western sense but a patronymic, his father's given personal name; Abd al-Majid his grandfather's; al-Tikriti means he was born and raised in (or near) Tikrit. He was commonly referred to as Saddam Hussein, or Saddam for short. The observation that referring to the deposed Iraqi president as only Saddam may be derogatory or inappropriate is based on the mistaken assumption that Hussein is a family name: thus, the New York Times incorrectly refers to him as "Mr. Hussein" [1], while Encyclop├Ždia Britannica prefers simply to use Saddam.

- ÔćĹ Under his government, this date was his official date of birth. His real date of birth was never recorded, but it is believed to be a date between 1935 and 1939. From Con Coughlin. Saddam The Secret Life. (London: Pan Books, 2003. ISBN 0330393103).

- ÔćĹ Elizabeth Bulmiller, "Was a Tyrant Prefigured by Baby Saddam?" New York Times, 2004-05-15. retrieved 2007-01-02

- ÔćĹ Hanna Batatu. The Old Social Classes & The Revolutionary Movement In Iraq. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979. ISBN 0691052417)

- ÔćĹ United Press International (2003), Saddam Key in Early CIA Plot, via NewsMax.com, April 11.

- ÔćĹ Saddam Hussein, CBC News, December 29, 2006 retrieved 23-02-2007

- ÔćĹ Jessica Moore, The Iraq War player profile: Saddam Hussein's Rise to Power, PBS Online Newshour. retrieved 22-02-2007

- ÔćĹ Majid Khadduri. Socialist Iraq. (Washington, DC: The Middle East Institute, 1978. ISBN 9780916808167)

- ÔćĹ BBC "On This Day" June 7, 1981, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/june/7/newsid_3014000/3014623.stm " 1981: Israel bombs Baghdad nuclear reactor"], retrieved 22-02-2007

- ÔćĹ George Washington University, National Security Archives, [2] retrieved 23-02-2007

- ÔćĹ Kevin Woods, James Lacey, and Murray Williamson,"Saddam's Delusions: The View From the Inside", Foreign Affairs, (May/June 2006) retrieved 22-02-2007

- ÔćĹ Al Isa, Dr Khalil Ibrahim Iraqi Scientist Reports on German, Other Help for Iraq Chemical Weapons Program, Al Zaman (London), December 1, 2003 retrieved 23-02-2007

- ÔćĹ US Department of StateSaddam's Chemical Weapons Campaign: Halabja, March 16, 1988 retrieved 23-02-2007 - Bureau of Public Affairs

- ÔćĹ Stephen C. Pelletiere, OPINION, January 31, 2003, "A War Crime or an Act of War?" New York Times, Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ÔćĹ A free-access on-line archive relating to U.S.-Iraq relations in the 1980s is offered by The National Security Archive of the George Washington University. It can be read on line at [3]. The Mount Holyoke International Relations Program also provides a free-access document briefing on U.S.-Iraq relations (1904 - present); this can be accessed on line at [4]. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ÔćĹ Malcolm Byrne, (ed.), 2003-12-18, Saddam Hussein: More Secret History. The GWU National Security Archive. accessdate 2007-01-02 [5] Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ÔćĹ Malcolm Byrne, (ed.), 1991-01-15, Responding to Iraqi Aggression in the Gulf. The GWU National Security Archive. accessdate=2007-01-02 [6] Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ÔćĹ Ruth Marcus, 2006-03-21 Man Overboard. The Washington Post, quote "Don't go wobbly on me, George." accessdate 2007-01-02

- ÔćĹ Mass grave unearthed in Iraq city. BBC News, 2005-12-27 accessdate 2007-01-02

- ÔćĹ Remarks by the President in address to the Nation, Clinton Foundation, June 26, 1993

- ÔćĹ U.S. Strikes Iraq for Plot to Kill Bush, Washington Post, June 27, 1993, Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ÔćĹ U.N. asks why its weapons inspectors abandoned Iraq, CNN.com, November 11, 1998 retrieved 23-02-2007

- ÔćĹ U.N. asks why its weapons inspectors abandoned Iraq, CNN.com, November 11, 1998 retrieved 23-02-2007

- ÔćĹ Richard Butler. Saddam Defiant. (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000. ISBN 9780297646006), 224

- ÔćĹ William J. Clinton, The Iraq Liberation Act, Statement by the President, October 31, 1998. retrieved 23-02-2007

- ÔćĹ Palestinians get Saddam funds. BBC News, 2003-03-13. accessdate 2006-12-31

- ÔćĹ Saddam Pays 25K for Palestinian Bombers. Fox News, 2002-03-26. accessdate 2006-12-31

- ÔćĹ Nets Pounce on No bin Laden-Saddam Link, But Bush Believed Media. Media Research Center, June 17, 2004. [7] mediaresearch.org. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ÔćĹ Behind The Scenes With Saddam. CBS News, 2003-02-24.

- ÔćĹ Saddam 'caught like a rat' in a hole. CNN.com. 2003-12-15.

- ÔćĹ Saddam pressed about insurgency. CNN.com 2003-12-16. accessdate 2007-01-02

- ÔćĹ Nurse tells of 'gardener' Saddam. BBC News, 2007-01-01. accessdate 2007-01-02

- ÔćĹ "Saddam Formally Charged" Softpedia, 2006-05-15. retrieved 2007-01-02

- ÔćĹ Fox News, 2006-03-15, "Judge Closes Trial During Saddam Testimony". retrieved 2006-12-31

- ÔćĹ Iraqis gather in Saddam hometown after burial. Reuters 2006-12-30 MSNB.com. Retrieved 2006-12-30

- ÔćĹ CNN News, 2003-07-22, "Pentagon: Saddam's sons killed in raid" retrieved 2006-12-31

- ÔćĹ Martha Sherrill, Jan. 25, 1991, "Bride of Saddam, Matched Since Childhood" The Washington Post, retrieved 2007-01-06

- ÔćĹ Michael Harvey, "Saddam's Billions", The Herald Sun Jan 2, 2007 retrieved 2007-01-06

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Balaghi, Shiva. Saddam Hussein: a biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006. ISBN 9780313330773.

- Batatu, Hanna. The Old Social Classes & The Revolutionary Movement In Iraq. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979. ISBN 0691052417.

- Butler, Richard. Saddam Defiant. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000. ISBN 9780297646006.

- Coughlin, Con. Saddam: The Secret Life. London: Pan Books, 2003. ISBN 0330393103.

- Kaplan, Lawrence, and William Kristol. The war over Iraq: Saddam's tyranny and America's mission. San Francisco, CA: Encounter Books, 2003. ISBN 9781893554696.

- Karsh, Efraim and Inari Hussein Rautsi. Saddam Hussein: a political biography. Toronto: Maxwell Macmillan Canada, 1991. ISBN 9780029170632.

- Khadduri, Majid. Socialist Iraq. Washington, DC: The Middle East Institute, 1978. ISBN 9780916808167.

- Mackey, Sandra. The reckoning: Iraq and the legacy of Saddam Hussein. NY: Norton, 2002. ISBN 9780393051414.

- Miller, Judith, and Laurie Mylroie. Saddam Hussein and the crisis in the Gulf. NY: Times Books, 1990. ISBN 9780812919219.

- Munthe, Turi, ED. The Saddam Hussein Reader: Selections from Leading Writers on Iraq. NY: Thunder's Mouth Press, 2002. ISBN 9781560254287.

- Sciolino, Elaine. The outlaw state: Saddam Hussein's quest for power and the Gulf crisis. NY: Wiley, 1991. ISBN 9780471542995.

- Woods, Kevin, James Lacey, and Murray Williamson,"Saddam's Delusions: The View From the Inside", Foreign Affairs, (May/June 2006) retrieved 22-02-2007

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Saddam Hussein profile BBC News

- The Saddam Hussein Sourcebook National Security Archive

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.