Hammurabi

| Hammurabi | |

| Born | c. 1795 B.C.E. (middle) |

|---|---|

| Died | c. 1750 B.C.E. (middle) |

| Title | King of Babylon |

| Successor | Samsu-Iluna |

Hammurabi (Akkadian from Amorite ˤAmmurāpi, "the kinsman is a healer," from ˤAmmu, "paternal kinsman," and Rāpi, "healer;" (c. 1795–1750 B.C.E. middle chronology) was the sixth king of Babylon. He became the first king of the Babylonian Empire, extending Babylon's control over Mesopotamia by winning a series of wars against neighboring kingdoms. He was a very efficient ruler, giving the region stability after turbulent times, and transforming what had been an unstable collection of city-states into an empire that spanned the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia.

A great literary revival followed. One of the most important works of this "First Dynasty of Babylon," as the native historians called it, was the compilation of a code of laws. This was made by order of Hammurabi after the expulsion of the Elamites and the settlement of his kingdom. A copy of the Code of Hammurabi was found in 1901 by J. de Morgan at Susa, and is now in the Louvre. This code recognized that kingly power derived from God and that earthly rulers had moral duties, as did their subjects. It laid out Hammurabi's task “to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers” and to fear God. Hammurabi's code was one of the first written codes of law in recorded history. These laws were written on a stone tablet, or stele, standing over six feet tall.

Although his empire controlled all of Mesopotamia at the time of his death, his successors were unable to maintain it.

History

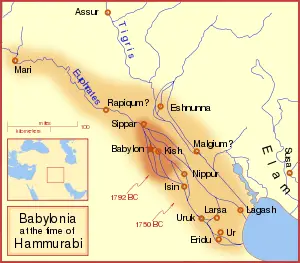

Hammurabi was a First Dynasty king of the city-state of Babylon, and inherited the throne from his father, Sin-muballit, in c. 1792 B.C.E.[1] Babylon was one of the many ancient city-states that dotted the Mesopotamian plain and waged war on each other for control of fertile agricultural land.[2] Though many cultures co-existed in Mesopotamia, Babylonian culture gained a degree of prominence among the literate classes throughout the Middle East.[3] The kings who came before Hammurabi had begun to consolidate rule of central Mesopotamia under Babylonian hegemony and, by the time of his reign, had conquered the city-states of Borsippa, Kish, and Sippar.[3] Thus Hammurabi ascended to the throne as the king of a minor kingdom in the midst of a complex geopolitical situation. The powerful kingdom of Eshnunna controlled the upper Tigris River while Larsa controlled the river delta. To the east lay the kingdom of Elam. To the north, the Shamshi-Adad I was undertaking expansionistic wars,[4] although his untimely death would fragment his newly conquered Semitic empire.[5]

The first few decades of Hammurabi's reign were relatively peaceful. Hammurabi used this time to undertake a series of public works, including heightening the city walls for defensive purposes, and expanding the temples.[6] In c. 1766 B.C.E., the powerful kingdom of Elam, which straddled important trade routes across the Zagros Mountains, invaded the Mesopotamian plain.[7] With allies among the plain states, Elam attacked and destroyed the empire of Eshnunna, destroying a number of cities and imposing its rule on portions of the plain for the first time.[8] In order to consolidate its position, Elam tried to start a war between Hammurabi's Babylonian kingdom and the kingdom of Larsa.[9] Hammurabi and the king of Larsa made an alliance when they discovered this duplicity and were able to crush the Elamites, although Larsa did not contribute greatly to the military effort.[9] Angered by Larsa's failure to come to his aid, Hammurabi turned on that southern power, thus gaining control of the entirety of the lower Mesopotamian plain by ca. 1763 B.C.E.[10]

As Hammurabi was assisted during the war in the south by his allies from the north, the absence of soldiers in the north led to unrest.[10] Continuing his expansion, Hammurabi turned his attention northward, quelling the unrest and soon after crushing Eshnunna.[11] Next, the Babylonian armies conquered the remaining northern states, including Babylon's former ally Mari, although it is possible that the "conquest" of Mari was a surrender without any actual conflict.[12] In just a few years, Hammurabi had succeeded in uniting all of Mesopotamia under his rule.[6] Of the major city-states in the region, only Aleppo and Qatna to the west in Syria maintained their independence.[6] However, one stele of Hammurabi has been found as far north as Diyarbekir, where he claims the title "King of the Amorites."[13]

Vast numbers of contract tablets, dated to the reigns of Hammurabi and his successors, have been discovered, as well as 55 of his own letters.[14] These letters give a glimpse into the daily trials of ruling an empire, from dealing with floods and mandating changes to a flawed calendar, to taking care of Babylon's massive herds of livestock.[15] Hammurabi died and passed the reins of the empire on to his son Samsu-Iluna in ca. 1750 B.C.E.[16]

Code of laws

Hammurabi is best known for the promulgation of a new code of Babylonian law: The Code of Hammurabi. This was written on a stele, a large stone monument, and placed in a public place so that all could see it, although it is thought that few were literate. The stele was later plundered by the Elamites and removed to their capital, Susa; it was rediscovered there in 1901, and is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris.[17] The code of Hammurabi contained 282 laws, written by scribes on 12 tablets. Unlike earlier laws, it was written in Akkadian, the daily language of Babylon, and could therefore be read by any literate person in the city.[18]

The Code consists of rules and punishments if those rules are broken. The structure of the code is very specific, with each offense receiving a specified punishment. It focuses on theft, agriculture (or shepherding), property damage, women's rights, marriage rights, children's rights, slave rights, murder, death, and injury. The punishment varies depending on the class of offenders and victims, with upper classes, who are expected to be more responsible, receiving harsher punishments.

The punishments tended to be harsh by modern standards, with many offenses resulting in death, disfigurement, or the use of the "Eye for eye, tooth for tooth" (Lex Talionis "Law of Retaliation") philosophy. Putting the laws into writing was significant because it suggested that the laws were immutable and above the power of any earthly king to change. The code is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence. However, there is no provision for extenuating circumstances to alter the prescribed punishment.

A carving at the top of the stele portrays Hammurabi receiving the laws from the god Shamash, and the preface states that Hammurabi was chosen by the gods of his people to bring the laws to them. Parallels to this divine inspiration for laws can be seen in the laws given to Moses for the ancient Hebrews. Similar codes of law were created in several nearby civilizations, including the earlier neo-Sumerian example of Ur-Nammu's code, and the later Hittite code of laws.[19]

Legacy

Under the rules of Hammurabi's successors, the Babylonian Empire was weakened by military pressure from the Hittites, who sacked Babylon around 1600 B.C.E.[20] However, it was the Kassites who eventually conquered Babylon and ruled Mesopotamia for 400 years, adopting parts of the Babylonian culture, including Hammurabi's code of laws.

Because of Hammurabi's reputation as a lawgiver, his depiction can be found in several U.S. government buildings. Hammurabi is one of the 23 lawgivers depicted in marble bas-reliefs in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol.[21] An image of Hammurabi receiving the Code of Hammurabi from the Babylonian sun god (probably Shamash) is depicted on the frieze on the south wall of the U.S. Supreme Court building.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Marc Van De Mieroop, King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography (Blackwell Publishing, 2005, ISBN 1405126604), 1.

- ↑ Van De Mieroop, 2005, 1–2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Van De Mieroop, 2005, 3.

- ↑ Van De Mieroop, 2005, 3–4.

- ↑ Van De Mieroop, 2005, 16.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Bill T. Arnold, Who Were the Babylonians? (Brill Publishers, 2005, ISBN 978-9004130715).

- ↑ Van De Mieroop, 2005, 15–16.

- ↑ Van De Mieroop, 2005, 17.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Van De Mieroop, 2005, 18.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Van De Mieroop, 2005, 31.

- ↑ Van De Mieroop, 2005, 40–41.

- ↑ Van De Mieroop, 2005, 54–55.

- ↑ Albert Tobias Clay, The Empire of the Amorites (University of Michigan Library, 1919).

- ↑ James Henry Breasted, Ancient Time or a History of the Early World, Part 1 (Kessinger Publishing, 2003, ISBN 0766149463), 129.

- ↑ Breasted, 2003, 129–130.

- ↑ Arnold, 2005, 42.

- ↑ L.W. King, The Code of Hammurabi (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012, ISBN 978-1470100896).

- ↑ Breasted, 2003, 141.

- ↑ W.W. Davies, Codes of Hammurabi and Moses (Kessinger Publishing, 2003, ISBN 0766131246).

- ↑ Lukas DeBlois, An Introduction to the Ancient World (Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0415127734), 19.

- ↑ Architect of the Capital, Hammurabi. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, Courtroom Friezes. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arnold, Bill T. Who Were the Babylonians? Brill Publishers, 2005. ISBN 978-9004130715.

- Breasted, James H. Ancient Time or a History of the Early World, Part 1. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766149463.

- Clay, Albert T. The Empire of the Amorites. University of Michigan Library, 1919. ASIN B003TSERAE

- Davies, W.W. Codes of Hammurabi and Moses. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766131246.

- DeBlois, Lukas. An Introduction to the Ancient World. Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415127734.

- King, L.W. The Code of Hammurabi. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012. ISBN 978-1470100896.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Blackwell Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1405126604.

External links

All links retrieved June 22, 2024.

| Preceded by: Sin-muballit |

Kings of Babylon |

Succeeded by: Samsu-Iluna |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.