Polygamy

|

| Family law |

|---|

| Entering into marriage |

| Marriage |

| Common-law marriage |

| Dissolution of marriage |

| Annulment |

| Divorce |

| Alimony |

| Issues affecting children |

| Illegitimacy |

| Adoption |

| Child support |

| Foster care |

| Areas of possible legal concern |

| Domestic violence |

| Child abuse |

| Adultery |

| Polygamy |

| Incest |

The term polygamy (literally many marriages in late Greek) is used in related ways in social anthropology and sociobiology. In social anthropology, polygamy is the practice of marriage to more than one spouse simultaneously (as opposed to monogamy where each person has only one spouse at a time). Like monogamy, the term is often used in a de facto sense, applying regardless of whether the relationships are recognized by the state. In sociobiology, polygamy is used in a broad sense to mean any form of multiple mating. Polygamy is condemned or restricted by the majority of the world's religions. Anthropologists have observed that, while many societies have permitted polygamy, the majority of human partnerships are in fact monogamous.

Historically, human beings have been immature, failing to fulfill their unique potential as individuals, and consequently failing to achieve successful partnerships and families based on true love. The solution to happiness and fulfillment on the individual, family, societal, and world levels is not to be found in polygamy, but rather in individuals who grow to maturity and then commit to an exclusive partnership with another mature individual, each fulfilling the other's needs and hopes in a relationship of true love.

Forms of polygamy

Human polygamy exists in three specific forms, including polygyny (one man having multiple wives), polyandry (one woman having multiple husbands), and group marriage (some combination of polygyny and polyandry). Historically, all three practices have been found, but polygyny is by far the most common.

A notable example of polyandry occurs in Hindu culture in the Mahabharata, where the Pandavas are married to one common wife, Draupadi. Today it is almost exclusively observed in the Toda tribe of India, where it is sometimes the custom for several brothers to share one wife. In this context, the practice is intended to keep land (a precious resource in a populous country like India) from being split up amongst male heirs. Polyandry was also traditionally practiced among nomadic Tibetans, where it meant two poor brothers sharing a wife.

Group marriage, or "circle marriage," may exist in a number of forms, such as where more than one man and more than one woman form a single family unit, and all members of the marriage share parental responsibility for any children arising from the marriage. Another possible arrangement, which may occur only in science fiction, is the long-lived "line marriage" in which deceased or departing spouses in the group are continually replaced by others, so that family property remains in the lineage through inheritance.

A related term is "bigamy," which refers to someone who has two spouses at the same time. Many countries have specific statutes outlawing bigamy, making any secondary marriage a crime. "Trigamy" refers to someone who has three spouses at the same time. From the legal perspective, this is defined as two counts of bigamy.

In countries where polygamy is recognized, usually the law stipulates that they must declare whether the marriage is monogamous or polygamous at the start. However, laws are not limited to cases of traditional polygamy, where there is some tradition of polygamy and spouses may know about each other. Bigamy also covers cases where a man is married, and without divorcing his wife, marries another woman. It even covers the occasional case of a man who sets up a second family with a second wife, keeping his dual marriage a secret from one or both of them. In both of these cases, the effect of these laws is to protect people from being married under false pretenses. In many countries and some states within the United States, there is some reluctance to prosecute bigamy cases and the laws remain unenforced.

Within the animal kingdom, many species have multiple pairings. A common pattern is one "alpha" male mating with several females, and one female who leads the female grouping. Together they may be referred to as the alpha pair. Lions, chimpanzees, and canines, including wolves, are among many others that follow this pattern. Other males in the social group usually must fend for themselves and may not have mating privileges.

Polygamy worldwide

According to the Ethnographic Atlas Codebook derived from George Peter Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas (1981), which recorded the marital composition of 1231 societies, from 1960-1980, 186 societies were monogamous, 453 had occasional polygyny, 588 had more frequent polygyny, and seven had polyandry. The distribution of polygamous relationships within the world is rarer than these data may suggest.

Even within societies which allow polygamy, in actual practice it generally occurs only rarely. To take on more than one wife often requires considerable resources: this may put polygyny beyond the means of the vast majority of people within those societies. Such appears the case in many traditional Islamic societies and historically within Imperial China. India has an occurrence of polygamy about four percent of the Hindu population and about three percent within the Islamic population. The practice of polygamy within the various cultures of Africa is traditional, with either Islamic (supportive) or Christian (prohibitive) colonial influences. However, even within those countries with both Islamic and traditional support for polygamy, the majority of the population never practice such relationships.

There are basically three factors that influence the occurrence of polygynous polygamy. Some societies, particularly in tropical regions, have a long post-partum sex taboo. Infants are particularly susceptible to certain tropical diseases, and nursing provides some protection. To keep her milk, a woman may refrain from sexual activity for up to two years, at which point the infant is stronger. Often the women feel that in such a long time her partner will seek other sexual partners. To know about another wife may be preferable to an unknown other woman.

Another factor that seems to promote polygyny is an imbalance of men to women. Statistics indicate that societies with a high male mortality rate have a higher incidence of polygyny. The imbalance in such societies is often due to warfare.

The third factor increasing the incidence of polygyny is men marrying later in life, although the factors leading to men marrying late are unclear.

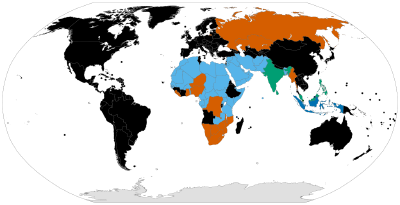

██ Polygamy is legal only for Muslims ██ Polygamy is legal ██ Polygamy is legal in some regions (Indonesia) ██ Polygamy is illegal, but practice is not criminalized ██ Polygamy is illegal and practice criminalized ██ Legal status unknown

In Nigeria and South Africa, polygamous marriages under customary law and for Muslims are legally recognized.

Within some polygynous societies, multiple wives become a status symbol denoting wealth and power. Sometimes this is actually a by-product of how the women care for agriculture, as in the Siwai society in the South Pacific. There, social status depends on pigs and since women care for the pigs, having multiple wives increases a man's the ability to have more pigs. Some wives may want helpers with the work and childcare that comes from other wives. This concurs with the occurrence of polygyny primarily in rural areas where additional helpers are particularly useful in agricultural settings.

There is much reported about jealousy and fighting within some polygynous societies. Yet this does not occur as frequently in some societies as in others. Factors that create less tension include societies where co-wives are sisters, known as "sororal" polygyny. In such societies, such wives may share a residence. Clarity and societal enforcement of rules of conduct also decrease tension. Some societal rules enforce the man's frequency of co-habitation, and consider it an act of adultery if the rules are not followed. The Tanala of Madagascar allow a woman slighted in this way to sue for divorce and up to one third of her husband's assets. In societies where the first wife is given seniority rights in all household judgments, such as in Tonga, there also seems to be less stress.

Polygamy and religion

Confucianism

Since the Han Dynasty, technically, Chinese men could have only one wife. However throughout Chinese history, it was common for rich Chinese men to have a wife and various concubines. Although these women were concubines, they had certain marginal legal rights and the children were given a status, although much lower than those from the "first" wife. They were subservient to the "first" wife who ran the household. This polygyny was a by-product of the tradition of emphasis on procreation and the continuity of the father's family name. Before the establishment of the People's Republic of China, it was lawful to have a wife and multiple concubines. Emperors, government officials, and rich merchants had up to hundreds of concubines after marrying their first wives.

In Confucianism, the ability of a man to manage a family, which usually meant more than one wife and set of children, was emphasized as part of the steps of learning for personal growth. The Chinese culture of Confucianism and thus the practice of polygyny spread from China to the areas that are now Korea and Japan.

Islam

According to traditional Islamic law, a man may take up to four wives, and each of those wives must have her own property, assets, and dowry. The Qur'an also stipulates that a husband must be able to love them equally. The Qur'an in verse 4:3 states (English translation by Muhammad Taqi-ul-Din Al Hilali and Muhammad Muhsin Khan):

And if you fear you shall not be able to deal justly with the orphan girls, then marry (other) women of your choice; 2, 3 or 4, but if you fear you may not be able to deal justly (with them) then only one.

This verse is linked to the preceding verse which describes a man taking an orphaned girl as his wife. The caregivers of these orphan girls have an unfair advantage (especially during the time during which the Qur'an was revealed) over them if they wish to marry them. As their guardians, they may be tempted to marry them without paying them their full dowries or in order to confiscate their inheritance. This verse tell such men that if they fear that they cannot deal justly with the orphans whom they wish to marry, then they should marry other women (not orphaned women but free women with guardians and families who can look over and protect their rights). However, the verse could also have another meaning, such as if a person is worried about not treating orphan(s) under his care fairly, he could have a wife or wives to delegate the tasks of taking care of them.

It is important to note the context within which the term "orphan girls" is being used. Orphaned girls (that is, orphaned of both mother and father as well as any immediate family to look after them) at the time when the Qur'an was revealed had very low status in society and virtually no recognizable rights, unless a caregiver chose to take them in. The relationship of the caregiver to the orphaned girl would have to satisfy the criteria set out in the Qur'an verses 4:23 and 4:24 as to which women a man is permitted to marry under Islamic law in order for verse 4:3 to be valid.

Some Muslims, however, believe that polygamy is restricted. They quote the following verse 4:129, (translation by Yusuf Ali):

Ye are never able to be fair and just as between women, even if it is your ardent desire: But turn not away (from a woman) altogether, so as to leave her (as it were) hanging (in the air). If ye come to a friendly understanding, and practice self-restraint, Allah is Oft-forgiving, Most Merciful.

This, combined with the requirement for fairness stated in 4:3 and arguments based on its context, has led to the conclusion that polygamy is only sanctioned in exceptional circumstances, such as when there is a shortage of male adults after a war, and that monogamy is generally preferable. Opponents of this view believe that verse 4:129 does not seek to discourage polygamy, but instead guides the husband on how to treat all of his wives fairly in practice, even though he may not be able to love them equally.

Islamic polygamists point out that an imbalance of the ratio of men to women means that polygamy serves to help women maintain a respectable presence. In their defense, they cite cases in supposedly monogamous societies where women may become mistresses to men with a legal wife, and be in a forbidden, shameful relationship. Also, the practice within monogamy of simply taking one wife after another leaves the first woman abandoned and in a more shameful and un-protected state. As a co-wife, they have legal rights and status.

Usually wives have little to no contact with each other and lead separate, individual lives in their own houses, and sometimes in different cities, though they all share the same husband. Thus, polygamy is traditionally restricted to men who can manage things efficiently. In West Africa the education of men increases the incidence of polygamy, but the education of women decreases their participation in such relationships.

Hinduism

Both polygamy and polyandry were practiced in ancient times among certain sections of the Hindu society. Except for Brahmins, Hinduism does not prohibit polygamy, nor encourage it. Brahmins have never been allowed to marry more than once. The elective nature of marriage within Hinduism in general is because it is expensive to have more than one wife and many children, and hard to dedicate the time required to raise the family well. Historically, only kings, in practice, were polygamous, and this in part because they could afford it. For example, the Vijaynagara emperor, Krishnadevaraya had multiple wives. Hinduism, and other religions such as Buddhism and Jainism, actually consent for a man or woman to marry more than one person. Polyandry, where a woman has more than one husband, has never been popular and is a rare, exceptional case.

Marriage laws in India are dependent upon the religion of the subject in question; the law only recognizes polygamous marriages for the Muslim population. Thus, Indian law prohibits Hindus from having more than one marriage partner while Islamic people in India are allowed to have multiple wives. There have been efforts to propose a uniform marital law that would treat all Indians the same, irrespective of religion.

Judaism

Although classical Jewish literature indicates that polygamy was permitted at an earlier time, it was later outlawed. Scriptural evidence indicates that polygamy, though not extremely common, was not particularly unusual among the ancient Hebrews, and certainly not prohibited or discouraged. One source of polygamy was the practice wherein a man was required to marry and support his deceased brother's widow. The Hebrew Scriptures tell of approximately 40 polygamists, including prominent figures such as Abraham, Moses, Jacob, Esau, and David, with little or no further remark on their polygamy as such. The Torah (the first five books of the Christians Old Testament) includes a few specific regulations on the practice of polygamy. Exodus 21:10 states that multiple marriages are not to diminish the status of the first wife; Deuteronomy 21:15-17 states that a man must award the inheritance due to a first-born son to the son who was actually born first, even if he hates that son's mother and likes another wife more; and Deuteronomy 17:17 states that the king shall not have too many wives.

Polygamy has now been outlawed by rabbinic Judaism. First was Ashkenazi Jewry, which followed Rabbenu Gershom's ban since the eleventh century. Some Sephardi and Mizrahi groups discontinued polygamy much later, to the point that Israel had to make provisions for polygamous families immigrating after its 1948 creation. Many Jewish families from countries such as Iran and Yemen were assimilated to the general cultural norm of a family made up of a man, two or more wives, and their children. New polygamous marriages are, however, forbidden in Israel.

Christianity

Saint Augustine saw a conflict with Old Testament polygamy, and wrote about it in The Good of Marriage (chapter 15, paragraph 17), where he stated that though it "was lawful among the ancient fathers: whether it be lawful now also, I would not hastily pronounce. For there is not now necessity of begetting children, as there then was, when, even when wives bear children, it was allowed, in order to a more numerous posterity, to marry other wives in addition, which now is certainly not lawful." He declined to judge the patriarchs, but did not deduce from their practice the ongoing acceptability of polygamy. In another place, he wrote, "Now indeed in our time, and in keeping with Roman custom, it is no longer allowed to take another wife, so as to have more than one wife living [emphasis added]."

The Catholic Church clearly condemns polygamy in their canon. The Catechism of the Catholic Church in paragraph 2387 under the head "Other offenses against the dignity of marriage" states that it "is not in accord with the moral law." Also paragraph 1645 under the head "The Goods and Requirements of Conjugal Love" states "The unity of marriage, distinctly recognized by our Lord, is made clear in the equal personal dignity which must be accorded to man and wife in mutual and unreserved affection. Polygamy is contrary to conjugal love which is undivided and exclusive."

Periodically, Christian reform movements that have aimed at rebuilding Christian doctrine based on the Bible alone (sola scriptura) have at least temporarily accepted polygamy as a Biblical practice. During the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther advised Philip of Hesse that although he found nothing un-biblical about polygamy, he should keep his second marriage a secret to avoid public scandal (Mozley 1878). The radical Anabaptists of Münster also practiced polygamy, but they had little influence after the defeat of the Münster Rebellion in 1535. However, other Protestant leaders including John Calvin condemned polygamy. Sanctioned polygamy did not survive long within Protestantism, with modern Protestants believing that all forms of polygamy are condemned by the Bible, citing verses such as 1 Timothy 3:2. Saint Paul wrote "submit to the authorities, not only because of possible punishment but also because of conscience" (Romans 13:5), for "the authorities that exist have been established by God." (Romans 13:1) Saint Peter concurred when he said to "submit yourselves for the Lord's sake to every authority instituted among men: whether to the king, as the supreme authority, or to governors, who are sent by him to punish those who do wrong and to commend those who do right." (1 Peter 2:13,14)

Temporary exceptions to this doctrine have been found, however, under extreme circumstances, such as the loss of men due to extended warfare. Such a situation was reported by Jensen (1980), following the Thirty Years War:

On February 14, 1650, the parliament at Nürnberg decreed that because so many men were killed during the Thirty Years’ War, the churches for the following ten years could not admit any man under the age of 60 into a monastery. Priests and ministers not bound by any monastery were allowed to marry. Lastly, the decree stated that every man was allowed to marry up to ten women. The men were admonished to behave honorably, provide for their wives properly, and prevent animosity among them.

Mormonism

Although polygamy was not an original part of the Mormon doctrine, early in its history The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints allowed it. Their doctrine states that it is spiritually necessary to be married, and that marriage will be in the afterlife as well as our life on earth. Founder Joseph Smith Jr. received a revelation apparently recommending polygamy, recorded in 1843. This was referred to it as "plural marriage."

The revelation was supposedly dictated by Smith to his scribe William Clayton, and was shared with Smith's wife Emma later that day. Clayton wrote in his journal:

Wednesday 12th This A.M, I wrote a Revelation consisting of 10 pages on the order of the priesthood, showing the designs in Moses, Abraham, David and Solomon having many wives & concubines &c. After it was wrote Prests. Joseph & Hyrum presented it and read it to [Emma] who said she did not believe a word of it and appeared very rebellious. [Joseph]...appears much troubled about [Emma.]

The public revelation of the Church's practice of polygamy, however, led to escalated persecution. Many novelists began to write books and pamphlets condemning polygamy, portraying it as a legalized form of slavery. The outcry against polygamy eventually led to the federal government's involvement and the enacting of anti-polygamy laws. Although Latter-day Saints believed that their religiously-based practice of plural marriage was protected by the United States Constitution, opponents used it to delay Utah statehood until 1896. Increasingly harsh anti-polygamy legislation penalized Church members, unincorporated the Church, and permitted the seizure of Church property until the Church ordered the discontinuance of the practice in 1890. A "Second Manifesto" against polygamy was issued in 1904 that clarified that all members of the LDS Church were prohibited from performing or entering into polygamous marriages, no matter what the legal status of such unions was in their respective countries of residence. Since that time, it has been Church policy to excommunicate any member either practicing or openly advocating the practice of polygamy.

The ban on polygamy resulted in a schism within the Church, with various splinter groups leaving the Church. Mormon fundamentalists (who are not associated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) continue to practice polygamy, more than 100 years after the LDS Church discontinued the practice. These fundamentalists practice polygamy by tending to aggregate in communities where they all commonly share their own specific religious basis for polygamy. Notable polygamous communities (with over 500 residents) are located in Bountiful, British Columbia; Centennial Park, Arizona; Colorado City, Arizona; Hilldale, Utah; Ozumba, Mexico; Pinesdale, Montana; and Rocky Ridge, Utah.

Legality

Secular law in most countries with large Jewish and Christian populations does not recognize polygamous marriages. However, few such countries have any laws against living a polygamous lifestyle: they simply refuse to give it any official recognition. Parts of the United States, however, criminalize even the polygamous lifestyle; these laws originated as anti-Mormon legislation, although they are rarely enforced.

Muslim polygamy, in practice and law, differs greatly throughout the Islamic world. Polygamy is most widely practiced by Muslims in Africa (where it is also widely practiced by non-Muslims), as well as in certain traditionalist Arabian states such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In cultures where polygamy is still commonplace and legal, Muslim polygamists do not separate themselves from the society at large, since there would be no need as each spouse leads a separate life from the others. Polygamy is rare in the secular Arab states like Lebanon. In the non-Arab Muslim countries, such as Turkey and Malaysia, it is either extremely rare or even banned outright.

In Muslim countries where polygamy does occur, there are certain core fundamentals found in common among most of them. Often secular law confirms Sharia, or Islamic law, by which a man may marry only as many wives as he can afford to take care of properly, up to four in total. In many cultures, previous to Islam, some men would marry innumerable wives, and often there was much difficulty arising from these circumstances. From this perspective, Islam has often served to help and protect women and children who may have not been given rights without Sharia.

Many areas in Africa are heavily influenced by Sharia, even when Islamic people are not in a majority. The countries in Africa have multiple cultural and religious influences, and often the law reflects this diversity. The enforcement of law, however, is often done through local ethnic and religious affiliations and leadership. In North Africa, there is a very strong influence of Sharia. Although moderated by local customs, generally the Islamic view is followed. In West Africa, it becomes more diverse in application. Some Muslim and Christian areas have strict monogamy, and some are legally polygamous. In some Christian areas, polygamy is allowed within the law of the church for clergy who are currently within a polygamous marriage or, although it may be formally disapproved, it is simply ignored. South Africa is also diverse in application.

In India, the law depends on one's religious affiliation. Hindus are forbidden polygamy, while Islamic men are allowed up to four wives.

China had legal polygamy until the Communist government ruled that this was injurious to women who were equal workers with men. The State took over all legal aspects of marriage.

Justice for women and children

In Africa, a growing problem of justice for children and women within polygamy is challenging the con-flux of the various legal domains of Sharia, national, and tribal law. In many cases, although laws may have been enacted, they are not necessarily enforced. Christian groups basically support monogamy and individual rights that could help women and children, but some groups ignore the polygamous within their midst and may even have polygamous clergy. Questions of polygamy are often ignored in an effort to avoid conflicts of power between various domains of national, religious, or local authority. Many politicians believe they cannot lose the support of local leaders, and do not challenge practices that may be hurtful to women and children.

Recent polygamy cases

Polygamy within the United States presents interesting legal challenges. Without evidence, they are merely subject to the laws against adultery or unlawful cohabitation. These laws are not commonly enforced because they also criminalize other behavior that is otherwise socially sanctioned. However, some "Fundamentalist" polygamists marry women prior to the age of consent or commit fraud to obtain welfare and other public assistance.

In 2001, the state of Utah convicted Thomas Arthur Green of criminal non-support and four counts of bigamy for having five serially monogamous marriages, while living with his previous legally divorced wives. His cohabitation was considered evidence of a common-law marriage to the wives he had divorced while still living with them. That premise was subsequently affirmed by the Utah Supreme Court in State of Utah v. Green, as applicable only in the state of Utah. Green was also convicted of child rape and criminal non-support. In 2005, the state attorneys general of Utah and Arizona issued a primer on helping victims of domestic violence and child abuse in polygamous communities.

Polygamy in fiction

A number of writers have expressed their views on polygamy by writing about a fictional world in which it is the most common type of relationship. These worlds tend to be utopian or dystopian in nature. For instance, Robert A. Heinlein used this theme in a number of novels, such as Stranger in a Strange Land.

Polygamy is practiced by the Fremen in Frank Herbert's Dune as a means to pinpoint male infertility. It is socially accepted as long as the man provides for all wives equally. Cultures described within the Dune novel series have intentional similarities to Islamic, Arabic, and other cultures.

Arguments for and against polygamy

Polygamy has continued to be practiced in large numbers in the world into the beginning of the twenty-first century, primarily in Africa and some Islamic countries. In these countries, tradition and religion usually mix to form a confusion of law and application of law, creating problems of clear jurisdiction and/or officials who hesitate to enforce laws that may conflict with another's jurisdiction.

Typical abuses encountered in polygamous relationships involve the woman not even being aware of any other wives, as they have separate residences, with the result that the woman must effectively care for her children and the house alone. There are efforts to create and enforce local laws that would provide for responsibility from such husbands. Other abuses occur because the women may have little access or ability to make any income, and they become trapped in the marriage. Many are from traditional societies that would completely ostracize them if they left their marriage.

The Libertarian Party in the United States supports complete decriminalization of polygamy as part of a general belief that the government should not regulate marriage. The argument that polygamy tends to benefit most women and disadvantage most men has been used to support the legalization of polygamy (Friedman 1990).

The sexual partnering of a man and a woman is a complex relationship that impacts all aspects of their lives and continues over an extended period of time. The physical level of sexual activity involves personal health, with many diseases being sexually transmitted, as well as the potential for pregnancy, which leads to the responsibility of giving birth to a child. On the psychological level, entering into the most intimate of relationships has intense emotional consequences. The phrase, "broke my heart" reflects the depth of pain that follows termination of this relationship. Socially, when a large number of men and women in a society do not have stable partnerships, the society suffers as jealousy and other emotions disrupt the harmony of interpersonal relationships. A wife is not like a machine, or a vehicle, that can be "traded in" or put into storage when a newer, more exciting model becomes available. As the Qur’an states, a man should only have more than one wife if he is capable of loving and caring for them. When children are added into the picture, it is a great man indeed who can successfully love and care for multiple families.

The purpose of marriage is, ultimately, the next generation, children, and the continuation of one's lineage. The conjugal relationship of husband and wife is the emotional and physical foundation for building a family, in which children, produced through the love of man and woman, are nurtured and protected until they reach maturity, and embark on their own lives, which also involve the continuation of the lineage.

Childrearing is a major responsibility for human beings. Unlike most species in nature, the time period required to raise a human child extends far beyond the period of physical recovery from childbirth, and usually several siblings are born while the first child is still at home. The parenting process requires more than temporary bonding between adults, and is best carried out by a stable husband and wife couple, the biological parents of the children. Children naturally inherit not only physical characteristics and physical and material wealth, they also receive their social heritage from their parents. Beyond the benefit received through these types of inheritance, children raised in a stable family by their married parents, have been found, on average, to be "physically and mentally healthier, better educated, and later in life, enjoy more career success than children in other family settings" (Waite & Gallagher 2000, 124). On the other hand, children of divorce, single-parent families, and step-families are considerably more likely to have emotional and behavioral problems—they sometimes fail to graduate high school, abuse drugs and alcohol, engage in sexual activity as teenagers, suffer unwanted pregnancies, are involved in violence and crime, avoid marriage and child-bearing, get divorced, and commit suicide at higher rates than those raised by two married parents.

Generally, the world's religions condemn polygamy, or at least have restricted its practice, reflecting their concern with the spiritual implications of sexual partnership and the consequent birth of children. Anthropological surveys have reported that the most common form of marriage relationship in human society is monogamy, although the practice is often not strict monogamy, as individuals form temporary extra-marital relationships, or practice serial monogamy moving from one exclusive partnership to another. Such activities, however, tend to destabilize society causing pain to the individuals, and traumatic injury to any children involved. Sharing one's husband (polygyny) or wife (polyandry) with others is generally the cause of great emotional pain.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- 2004. State v. Green. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- 2005. "Chinese 'descendants of one man' " in BBC News online. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- Cairncross, John. 1974. After Polygamy Was Made a Sin: The Social History of Christian Polygamy. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710077300

- Campbell, James. 2005 (original 1869). TruthBearer.org The History and Philosophy of Marriage. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- Chapman, Samuel A. 2001. Polygamy, Bigamy and Human Rights Law. Xlibris Corp. ISBN 1401012442

- Ember, Carol R. and Melvin Ember. 2004. Cultural Anthropology. New Jersey: Pearson, Prentis Hall. ISBN 0131116363

- Friedman, David D. 1990. "The Economics of Love and Marriage" in Price Theory: An Intermediate Text. South-Western Publishing Co. ISBN 0538805641

- Hillman, Eugene. 1975. Polygamy Reconsidered: African Plural Marriage and the Christian Churches. New York: Orbis Books ISBN 0883443910

- Mozley, James Bowling. 1878. Essays, Historical and Theological. Vol 1, 403-404. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- Murdock, G. P. 1981. Atlas of World Cultures. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0822934329

- Smith, George D. 1995. An Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. ISBN 1560850221

- Waite, Linda J. and Maggie Gallagher. 2000. The Case for Marriage. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0767906322

- Wilson, E. O. 2000. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674002350

- Van Wagoner, Richard S. 1992 (original 1975). Mormon Polygamy: A History. Utah: Signature Books. ISBN 0941214796

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2023.

- polygamy Legal Information Institute (LII)

- Polygamy: What It Is and The Impact on Relationships Psycom

- What Is Polygamy? Very Well Mind

- Anti-Polygamy.org - A pro-polygamy website that analyzes anti-polygamy rhetoric and arguments.

- Pro-Polygamy.com - Provides op-eds and press releases on polygamy-related current events for the secular mass media

- Biblical Polygamy - Presents biblical exegesis of arguments to support polygamy and lists all the polygamists in the Bible

- Christian Polygamy Info - The definitive resource for general information about Christian Polygamy

- Truth Bearer Organization for Christian polygamy

- Polygamy The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints

- When is polygamy allowed in Islam?

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.