Love

Popularly, Love is any of a number of emotions and experiences related to a sense of strong affection or profound oneness. Depending on context, love can have a wide variety of intended meanings, including sexual attraction. Psychologists and religious teachings, however, define love more precisely, as living for the sake of another, motivated by heart-felt feelings of caring, affection, and responsibility for the other's well-being.

The ancient Greeks described love with a number of different words: Eros was impassioned, romantic attraction; philia was friendship; xenia was kindness to the guest or stranger. Agape love, which the Greeks defined as unconditional giving, became the keystone of Christianity, where it is exemplified in Christ's sacrificial love on the cross. Some notion of transcendental love is a salient feature of all the world's faiths. "Compassion" (karuna) in Buddhism is similar to agape love; it is represented by the bodhisattva, who vows not to enter Nirvana until he has saved all beings. Yet love encompasses all these dimensions, eros as well as agape.

Perhaps the best context in which to develop such love is the family, where the love that is given and received is of various kinds. Closest to agape love is the sacrifice and investment that parents willingly give on behalf of their children. Children, in turn, offer their parents filial devotion and respect that grows more profound with the passing years. Siblings care for and help one another in various ways. The love between spouses is a world in itself. Grandparents bear a profound regard for their grandchildren. All of these types of love have their distinctive features.

Love is universally desired, but love can be fraught with infidelity, deceit, possessiveness, unrealistic expectations, jealousy, and hate. Love, in fact, is at the root of much pain and conflict in the world. Marriages break down when the passion of romance cools. Religions like Buddhism and Roman Catholicism regard family love as incompatible with the higher life. Nevertheless, people still long for "true love," love that never fails. Psychologists and character educators hold that much of the heartbreak of failed love could be avoided by education about the nature of love, and by cultivating the self to be able to love well.

Definitions

Love is notoriously difficult to define. This is partly a difficulty of the English language, which uses the word "love" to cover such a wide variety of things. That is why English borrows heavily fromancient Greek, which employed different terms to characterize different types of affectionate human relationships: Eros for passionate romantic relationships; philia for friendship; xenia for kindness to guests or stranger; and agape for unconditional, sacrificial giving, regardless of any return.

In East Asia, love is expressed through the so-called "Five Relationships:" between parent and child, between husband and wife, between siblings, between friends, and between a ruler and his subjects. This way of thinking suggests that love is manifested differently in different social and interpersonal contexts. Furthermore, even within one of these contextsâsexual loveâlove can take on different qualities, such as infatuation, romantic love, and committed love.

In striving for an accurate definition of love, one can begin by comparing its opposites. As an expression of unique regard, commitment, and special intimacy, "love" is commonly contrasted with "like;" as a romantic relationship that is not primarily sexual but includes commitment and care, "love" is commonly contrasted with "lust;" and as an interpersonal relationship with romantic overtones, "love" is commonly contrasted with friendship.

Philosophers have long sought to define love. The Greek philosopher Empedocles (fourth century B.C.E.) argued that all motion in the universe was caused by the interplay of two forces: Love (philia) and strife (neikos). These two forces were said to intermingle with the classical elementsâearth, water, air, and fireâwith love serving as the binding power that links the various parts of existence harmoniously together. Most philosophers have recognized though that the essential quality of love is that it focuses on the other, not on the self. Thomas Jay Oord defined love as acting intentionally, in sympathetic response to others (including God), to promote overall well-being. Bertrand Russell described love as a condition of absolute value, as opposed to relative value.

Psychologists warn against a common misconception about love: To construe love as a feeling. According to Erich Fromm and M. Scott Peck, the popular usage of the word "love" to mean a fondness or affection felt by one person for another inevitably leads to disappointment, as feelings are fickle and affection can fade. They advocate the view that love is other-centered activity. In his classic, The Art of Loving, Fromm considers love to be an interpersonal and creative capacity of humans rather than an emotion. The key elements of love are "care, responsibility, respect," and "knowledge." Fromm argued that the common idea of "falling in love" was evidence of people's misunderstanding of the concept of love, as the narcissism and mistreatment of the object of such attention which often ensues are hardly creative. Fromm also stated that most people do not truly respect the autonomy of their partner, and are largely unaware of their partner's wants and needs. Genuine love involves concern for the other and the desire to satisfy their needs rather than one's own.[1] M. Scott Peck, in The Road Less Traveled, likewise taught that love is an activity or investment rather than a feeling. Peck even argues that romantic love is a destructive myth, leading to unhealthy dependency. He differentiates between love and instinctive attractions, such as to the opposite sex or to babies. The feelings of affection that these instincts generate are not love, Peck argues; however he admits that a certain amount of affection and romance is necessary to get sufficiently close to be able to truly love.[2]

An active definition of love fits best with popular understandings: In a poll of Chicago residents, the most favored definitions of "love" involve altruism, selflessness, friendship, union, family, and an enduring bond to another human being.[3] Thus, a good working definition of love is "to live for the sake of another, motivated by heart-felt feelings of caring, affection, and responsibility for the other's well-being."

Contexts of Love

Love is to be found in a variety of contexts. Conjugal love, parental love, friendship, compassion, love of self, love of country, love of Godâ"love" or its opposites can be found in all the diverse contexts for human relationships. This article's definitionâto live for the sake of another, motivated by heart-felt feelings of caring, affection, and responsibility for the other's well-beingâdescribes behaviors and attitudes that span all these contexts.

Family love

The family is where most people are introduced to the experience of love. Family love takes different forms, including conjugal love between spouses, parental love for children, children's love for their parents, and sibling relationships.

Children respond to their parents' caring by strongly bonding to their parents; from this early relationship they develop trust, empathy with others, and a sense of self-worth. Children's love includes feelings of respect and admiration for their parents, and is expressed by obedience and the desire to please their parents. Adult children will care for their aged parents and work to complete their parents' unfinished tasks and dreams. In Asia this type of love is called filial piety; yet it is fairly universal.

The opposite of a filial child is a spoiled child, who thinks and acts as though the universe revolves around him; this can be a problem especially in only children. Having siblings helps children shed self-centeredness and learn to share, to give, and to forgive. Parents can help older children become more other-centered by including them in the care of the new baby, activating altruism and rewarding it with praise. Like mentoring relationships in school, sibling love often respects the asymmetry in age between the children, establishing complementary roles between elder and younger siblings. Siblings can be a tremendous source of support, as they are usually close in age and can act as each other's friends and confidants. On the other hand, sibling rivalries sometimes create serious strife between siblings. Parents can often do much to ameliorate sibling rivalries by showing unconditional regard for all their children.

Conjugal love is the natural union between spouses and is the sign of a healthy marriage. This is one area where the sexual expression of love finds its natural place, blossoming and bearing fruit.

Parents' love for their children naturally calls forth investment and sacrifice. This love may be tested as the children grow into adolescents with their own needs, distinctive personalities, and divergent values. Tensions may develop, unless the parents are mature enough to give unconditional love to their children. Early in life, children often do not appreciate the role parents have played in providing support emotionally and materially. This is something the adult child realizes, making for strong bonds of gratitude and obligation in later life. Aristotle wrote that it is impossible for children to ever pay off the debt owed to their parents for raising them.

Grandparents have an innate need to give from their storehouse of knowledge and experience to enrich the younger generation. Opportunities to love grandchildren provide elders with "a higher sense of self."[4] As they watch their grown children shoulder the responsibility of parenthood, most are moved to help as much as they can. They give joyfully and share of their wisdom, knowing that their legacy will live on.

Friendship

Friendship is a close relationship between people. This type of love provides a great support system for those involved. Friends often share interests, backgrounds, or occupations. Friends can act as sources of fun, advice, adventure, monetary support, and self-esteem. Such relationships are usually based on mutual respect and enjoyment, and do not have a sexual component.

Like sibling relationships, friendships offer opportunities to build skills in problem-solving, social communication, cooperation in groups, and conflict resolution. They are forerunners to adult relationships in the workplace and prepare young people for marriageâthe "passionate friendship." According to psychologist Willard Hartrup:

Peer relations contribute substantially to both social and cognitive development and to the effectiveness with which we function as adults. Indeed, the single best childhood predictor of adult adaptation is not school grades, and not classroom behavior, but rather the adequacy with which the child gets along with other children. Children who⊠cannot establish a place for themselves in the peer culture are seriously at risk.[5]

Love in community

Love is also needed in the larger spheres of life beyond family and friends. Community involvement takes many forms, including helping neighbors in need, joining in service activities, watching out for criminal activity, volunteering for duties in local government bodies, helping with disaster relief, and charitable giving. Such ways of love in community increase one's sense of self-worth and widen one's circle of adult friends.

Patriotism at its best is expressed in voluntary sacrifice when one's country is under threat. Traditionally regarded as a virtue, it expresses solidarity with one's fellow-citizens and gratitude for the many benefits gained from one's country, its history, and the ideals it represents. In the modern world where nationalism is criticized for its partiality, people are coming to see themselves as members of a single global community and are expressing their global patriotism by volunteering for international serviceâfor example, the American Peace Corps, supporting Non-Governmental Organizations that serve the needs of the developing world, and charitable giving to help refugees and the victims of war and disaster throughout the world.

Rootedness in a loving family is an important foundation for love in community. Relationships in the family impart internal working models for relationships in the community. Studies of unusual altruismâpeople who rescued Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe, for exampleâindicate that the rescuers had warm relationships with their parents, thus increasing their empathy for others.[6] Children whose parents are of different races or religions are raised to practice tolerance and accept differences. Children who have warm, caring relationships with their parents and grandparents are more likely to be considerate to elderly people in general.

On the other hand, the negative social effects of family breakdown have been well documented.[7] Children of broken families are more likely to grow up to be prone to criminality, violence, and substance abuse. Crime rates have been shown to correlate with divorce and single parenting. Family life helps channel male aggressiveness into the constructive roles of responsible fatherhood. Family dysfunction, on the other hand, leaves mental and emotional scars which can impair relationships with co-workers, neighbors, and authority. The worst sociopathsâAdolf Hitler among themâwere brutally abused as children.

Love of the natural world

The ability to love and care for nature is an essentially human quality. People often develop strong emotional attachments to pets, who may reciprocate with loyalty and dependent appreciation. As the highest form of life on earth, human beings are in a special position to care for all things as loving stewards. Love for nature is encouraged by a sense of dependence and indebtedness to the earth, and gratitude for its provision, which sustains life and health. The natural world inspires us with its beauty and mysteryâthe poet William Blake wrote of seeing âa world in a grain of sand, And a heaven in a wild flower.â[8] Urban life far removed from nature impoverishes the emotions, or as the Lakota express it, âWhen a man moves away from nature his heart becomes hard.â

Hunting, fishing, and other sporting activities in nature promote the love of nature, and sportsmen often have a strong desire to preserve it unspoiled for subsequent generations. Thus it was the great sportsman Theodore Roosevelt who established the U.S. National Parks system. The solution to environmental problems begins by learning how to love the earth, all its wondrous featuresâmountains, rivers, oceans, trees, and so onâand all its living creatures.

Love of the things of the wider world begins with one's home environment and the things one uses: The house and yard, the car, and the spaces in which people live. Daily chores, cleaning, and repairing the things people use, is a way of loving those things. The environment responds to this love; there are numerous anecdotes, for example, about how an owner who loves his automobile can coax even a broken vehicle to run. A clean house and a well-running automobile add comfort and joy to life.

Love in work

"Work is your love made visible," said the poet Kahlil Gibran. The challenges of work can be an opportunity to express love, by appreciating one's given task from a transcendent perspective as one's small part in creating the great Universe. Martin Luther King, Jr. once remarked:

Even if it falls to your lot to be a street sweeper, go out and sweep streets like Michelangelo painted pictures; sweep streets like Handel and Beethoven composed music; sweep streets like Shakespeare wrote poetry; sweep streets so well that all the host of heaven and earth will have to pause and say, "Here lived a great street sweeper who did his job well."[9]

A day of hard work ends with refreshment, relaxation, and peace, all the sweeter if a person has given his or her all to the work of the day. The rewards of work include pride in a job well done, camaraderie with co-workers, respect, learning, gratitude from those for whom the work is performed, expressed in both monetary and non-monetary terms. Work performed with love thus elevates the worker in innumerable ways.

God's love

God's love is widely seen as his benevolence, mercy, and care upon human beings. This belief is not exclusive to those of Christian upbringing, but is held by people across all religions and is supported by holy texts in each. In Islam, the Qur'an describes God as "the Merciful, the Compassionate." The Jewish psalms praise God for his "loving-kindness" (chesed), by which he has preserved and guided his people throughout history. The Buddhist Gandavyuha Sutra says, "The Great Compassionate Heart is the essence of Buddhahood." The Christian Bible states, "God is love" (1 John 4:8). God's love is recognized in Jesus, who gave his life on the cross for human salvation, and through Jesus is seen the character of God the Father, who gave his only begotten Son for the sake of sinners. Many believers of all faiths consider themselves in a deep, personal relationship with God in which they are direct recipients of God's love and blessings, and of God's forgiveness for the sins of their former lives.

St. Augustine argued that God's goodness necessarily overflows into creation. The author of the letters of John wrote, "We love, because he first loved us" (1 John 4:19). People who are inspired by the love of God feel joy to sacrifice themselves for the sake of their beloved; which in the absence of God's love they would not do. The Bhagavad Gita states, "To love is to know Me/My innermost nature/The truth that I am" (18.55). Not only in the human world, but the beauty of nature can be regarded as an expression of God's love.

The Bible commands, "you should love the Lord your God, with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might" (Deuteronomy 6:4). The covenant relationship to God requires humans to respond to God's love by loving God in return. The Christian saints beginning with Paul endured many tribulations in their efforts to love God and do his will by preaching Christ to the unbelieving people. In the Qur'an, the believers are called "God's helpers" (61:14).

God's love is often seen as universal love. The concept that God needs people's help to do his will, which is to bring justice and peace to the earth, implies that there are myriads of opportunities to love God through loving other people and helping them in their distress. The Bible teaches, "If God so loved us, we also ought to love one another" (1 John 4:12). The Buddhist saint Nagarjuna wrote: "Compassion is a mind that savors only mercy and love for all sentient beings" (Precious Garland 437). The Bhagavad Gita describes in lofty terms the state of spiritual union encompassing all beings: "I am ever present in those who have realized Me in every creature. Seeing all life as My manifestation, they are never separated from Me. They worship Me in the hearts of all, and all their actions proceed from Me" (6:30-31).

Self-love

Self-love, depending on how it is construed, can be either the bane of genuine love or a necessary foundation for loving in all contexts. Where self-love is construed as self-centeredness, placing concern for self first, as in narcissism, it can be viewed entirely in the negative. The effort to live for the sake of the other that is genuine love requires giving up territories of self-centeredness at every turn.

Yet, without being able to love oneself, loving others is often difficult. It is hard to love others while hating oneself, and even harder to receive love when feeling unworthy. People need to love themselves enough to care for their health and strive to better themselves. The victories they gain in life give confidence, and confident people do better in life and are generally happier as a result (or vice versa). Self-love creates a positive attitude towards life that helps people deal with the everyday problems, rather than dwelling on negatives.

Loving oneself begins with the childhood experiences of loving parents. Abandoned babies, children raised in institutions or shuttled from foster home to foster home, find it difficult in later years to love deeply and make lasting bonds with other people.[10] Children also need to experience the obligations that loving parents impose, that responsibility and kindness win parental approval. From these experience, they learn to find self-worth in conquering the challenges of life's journey and striving in the realms of love.

Philosopher Thomas Aquinas posed the "problem of love" as whether the desire to do good for another is solely because the lover sees someone worth loving, or if a little self-interest is always present in the desire to do good for another. Aquinas understood that human expressions of love are always based partly on love of self and similitude of being:

Even when a man loves in another what he loves not in himself, there is a certain likeness of proportion: because as the latter is to that which is loved in him, so is the former to that which he loves in himself.[11]

Other thinkers, notably the Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov, have recognized that the essential quality of love is that it focuses on the other, not on the self. In The Meaning of Love, he wrote that love

forces us with all our being to acknowledge for another the same absolute central significance which, because of the power of our egoism, we are conscious of only in our selves.[12]

Personal development of competencies for loving

Love as an act of giving, living for the other, requires a set of competencies that one learns through a lifetime. Thus, Erich Fromm wrote of The Art of Loving.[13] He acknowledged that people seek love desperately, and often inappropriately, which he attributed to the fact that "the desire for interpersonal fusion is the most powerful striving in man." Yet since love is an interpersonal and creative capacity of humans rather than an emotion, the essential elements of loveâincluding empathy, caring, responsibility, and the wisdom to act in a way that will really benefit the otherâare "arts" that must be learned.

The family as the school of love

The family is the primary locus where most people cultivate their character and learn how to love. The family of origin is the context for a child's lessons about love and virtue, as he or she relates to parents and siblings. The challenges of marriage and parenting bring further lessons. Precisely because of this crucial role in character development, family dysfunction is the origin of some of the deepest emotional and psychological scars. Experiences of childhood sexual abuse, parents' divorce, and so forth lead to serious problems later in life.

The family structure provides the basic context for human development, as its members take on successive roles as children, siblings, spouses, parents, and grandparents. As educator Gabriel Moran put it, "The family teaches by its form."[14] These different roles in the family describe a developmental sequence, the later roles building upon the earlier ones. Each role provides opportunities to develop a particular type of love, and carries with it specific norms and duties. For this reason, the family has been called "the school of love."

Even though the family may be unsurpassed as a school of love, it can also convey bias and prejudice when love in the family is not on the proper foundation, cautions the Confucian Doctrine of the Mean. To rectify this problem, one must back up to consider the individual and the training he or she requires to be capable of true love.

Mind-body training to curb self-centeredness

Among the most important tasks in developing the ability to love others is to curb self-centeredness. Self-centeredness and the desires of the body can override the conscience, which naturally directs the mind towards the goodâwhat is best for everyone. Concern with the self can easily override the conscience's promptings to do altruistic deedsâsweep a neighbor's walk, give money to a passing beggar, or stop to help a motorist stuck on the road-side. "I don't have time," or "I need that money for my own kids," becomes a person's self-talk, and the conscience is overridden. Negative peer pressure, motivated by the self's desire to "fit in," can lead to cruel and unloving behavior. Sexual desire can lead to deceit and exploitation, to taking advantage of a friend who deserves better with blandishments of "I love you" for the sake of nothing more than the body's gratification.

To deal with this problem, people need training in self-discipline, the fruit of continuous practice of good deeds by curbing the more body-centered desires to conform to those of the mind. Theodore Roosevelt once said, âWith self-discipline most anything is possible.â Self-discipline is fundamental to character growth, which in turn is fundamental to the capacity to give genuine love. This training begins at a young age:

In a revealing study, preschoolers were given a choice of eating one marshmallow right away or holding out for fifteen minutes in order to get two marshmallows. Some youngsters ate the treat right away. Others distracted themselves to control their bodies from grabbing the treat; they were duly rewarded with two marshmallows. A follow-up study conducted years later when the children graduated from high school found that those who had displayed the ability to delay gratification even at that young age grew up to be more confident, persevering, trustworthy, and had better social skills; while the grabbers were more troubled, resentful, jealous, anxious, and easily upset.[15]

Thus, even a modicum of self-control at an early age sets up a pattern that leads to greater self-mastery.

Many religious teachings focus on ascetic practices to subjugate the desires of the flesh, in order to liberate the higher mind from its slavery to the body. In the Hindu Upanishads, the self is described as a rider, the body as a chariot, the intellect as the charioteer and the mind as the reins. The physical senses are likened to the power of the horses thundering down the mazes of desire (Katha Upanishad 1.3.3-6). This image shows that unless self-discipline is strong, the desires of the flesh enslave a person. Therefore, a person needs to establish self-control as a basis for his or her actions with others. âWho is strong? He who controls his passions,â states the Mishnah (Abot 4.1).[16]

Contemporary societyâs fondness for maximum individual freedom and autonomy presents challenges to those who would discipline themselves, and who would strengthen the moral will of those under their care. On one hand, society imposes far less external controls on individual behavior than it traditionally has; social expectations are quite lax on every matter from etiquette to sexual behavior. This would suggest that the locus of control must reside within the individual as never before. Yet there has probably never been less social support for individual self-control. Western consumer-oriented society exalts comfort and self-indulgence and scorns restraint and discipline. To instill self-control in oneself or others goes against the cultural tide. Yet it is an essential task. To conquer the realm of the body is an awesome responsibility which every person must undertake.

The religious traditions advocate two basic means to mind and body unity. One is to weaken the influence of the body by denying its desires. âOffer your bodies as living sacrifices, holy and pleasing to God,â exhorts St. Paul (Romans 12:1). This is the path of asceticism, which includes such training methods as fasting, reducing the amount of sleep, taking frequent cold showers, and quitting bad habits like smoking. The obedience of military life and living a simple and non-indulgent lifestyle are also recommended. The second path to mind-body unity is to reinforce the strength of the mind through various methods, including prayer, meditation, study of Scripture, mindfulness (becoming aware of one's states of mind and refraining from acting during unstable states like anger and complaint), setting and achieving worthy goals, respect for parents, and other lessons of family life.

To love even when it is difficult: This requires the capability of the mind to assert itself over the demands of the body. Through efforts to reduce the pull of the flesh while enhancing our moral and spiritual strength, the mind and body can be brought into unity. The heart is thus liberated to give of itself freely and unselfishly.

Conjugal Love

Conjugal love, including its sexual expression, is perhaps the most formidable of loves. It is inextricably intermingled not only with the impulse to bond for life but also the creation of life, and the passing down of genes and lineage. The power of sexual love is as deep and elemental as the wind or the sea and just as impossible to tame or even fully comprehend. For this reason, educating for true love necessarily involves imparting insights about sexuality and coaching in directing this marvelous force.

Sex within its rightful place of marriage is an expression of deepest trust and affection, bonding the two partners together in deep communion and joy. Spousesâ physical communion is the origin of families, which in turn are the schools for learning love and what it means to be human. Sex outside of marriage, however, is like a fire outside of its hearth, a threat to all concerned. It is uniquely prone to compulsiveness that overrides the conscience. Psychologist Rollo May differentiated between the impulse for love and the drive for sex, saying, "For human beings, the more powerful need is not sex per se but for relationships, intimacy, acceptance, and affirmation." Hence casual sex is built on the vain hope that satisfying the sexual impulses of the body will somehow satisfy the loneliness of the heart.[17] For these reasons, religious traditions and societies throughout history have provided strong guidelines for sexual expression. âThe moral man,â reads a Confucian text, âfinds the moral law beginning in the relation between man and womanâ (Doctrine of the Mean 12).[18]

The link between sex and love

The sex instinct is the biological counterpart to the spiritual heart impulse to love. Ethicist Lewis B. Smedes describes sexuality as the âhuman impulse towards intimate communion,â[19] which impels one towards a close connection with another person.

The very sex organs themselves give obvious testimony in biology to the principle of living for another and with another. This is at the core of what Pope John Paul II called the ânuptial meaning of the body,â that is, its capacity for union and communion through selfless giving.[20] In this sense, the genital organs symbolize the desire of the heart for conjugal oneness. The sexual parts of the body are the only organs that cannot fulfill their fullest function without their counterpart in a member of the opposite sex; they are almost useless otherwise. It is the same with the spiritual heart; it cannot find fulfillment without the beloved either. Indeed, the heart and the sexual parts are connected. One moves the other; there is a mysterious link of reinforcement between the communion of loversâ hearts and union of their genitals.

Thus, the man offers his body to the woman for her to experience the meaning of her own physical sexuality, and vice versa. This primal, inescapable need draws the two sexes to bridge the divide and lend their strengths and concede their weakness for one another. In this way, the sexual urge embodies the innate push of masculinity and femininity towards oneness, towards greater love and completeness.

This correspondence between the spiritual heart and the physical reproductive organs is the basis for the universal regard for sexual modesty, even among peoples who do not wear clothes. Just as individuals show self-respect by revealing their heart only to special people in their lives, so people honor the sexual parts of the body by hiding them from public view. If the body is the temple of the spirit, then this area represents the innermost sanctuary, the holiest place, the shrine and palace of love. A sense of the sacredness of the genital organs may have been behind the ancient Roman custom of men making oaths with their hand on their private parts. Certainly it helps to explain why Yahweh asked of Hebrew males to be circumcised and bear the mark of their special covenant with Him there.

Sacredness of sexuality

The way that partners utterly lose themselves during physical union has always suggested its transcendent side. This is one of the reasons people have historically posited sex as a spiritually elevating force in itself, heedless of its moral context, and even worshiped it. This perennial fallacy, coupled with the pernicious power of sex in generalânot to mention the ease with which even spiritually based personal relationships can become sexualized and destructiveâhave all contributed to why some of the world religions tend to scrupulously separate sex from matters relating to God.

Thus, although sex and spirituality are not commonly discussed together, it is simply a further reflection of the unique and paradoxical position humans occupy as spiritual yet embodied beings. Sexuality in many ways reflects this most dramatically. The sex urge is an instinctual drive yet it allows participants to co-create with God an eternal being (a child). It is a spiritual impulse towards oneness, even as it craves bodily expression and sensual play.

Likewise, one can surmise that God would be attracted to lovemaking between a fully mature husband and wife, mirroring as it does the fullness of the Divine heart. The couple's self-giving resonates with the self-giving nature of God. The unity of man and woman reflects the unity of masculinity and femininity in the Godhead. The conception of a child invites the presence of God in that moment, the creation of a new spiritual being.

Recognizing the sacredness of sexuality, Judaism teaches that that the Shekhinah (the feminine aspect of God) is present in marital relations, and encourages couples should make love on the Sabbath, the holiest day of the week. Islam has couples consecrating their lovemaking by offering a prayer. Buddhism and Hinduism contain secret Tantric teachings for initiates who have reached the requisite spiritual level to harness the powerful force of sexuality for self-realization.

The holiness of sexuality may be the reason behind many of the religious traditionsâ prohibitions against fornication, adultery, and lesser offenses. This negative emphasis invites charges of sexual repression. Yet one can argue that the purpose of these prohibitions is to highlight the sacredness, the unique importance and beauty of sexuality, and therefore it is a tribute to a fundamentally positive view of sex. In the Bible, even the older man is reminded, âLet your fountain be blessed and may you rejoice in the wife of your youth. A loving doe, a graceful deerâmay her breasts satisfy you always, may you ever be captivated by her loveâ (Proverbs 5.18-19).

Ascertaining the quality of conjugal love

Young people can benefit from a clear-eyed discussion about the nature of love that helps them distinguish between true conjugal love and its myriad of counterfeits. Conjugal love itself involves many elements, including romantic love, sex, deep friendship, and mature commitment to a life-long relationship. Inspiring examples from the culture and oneâs own family and neighbors can illuminate ennobling ties between men and women.

Love vs. infatuation

The most basic distinction is between genuine love and infatuationâthe common feeling of love based mainly on sexual attraction and passion. Infatuation is characteristic of immature, self-centered "love." Couples whose feelings for one another are at the level of infatuation enjoy the passion of sexual love without the volitional aspect of living for the sake of the other in rough times as well as in good times. Their love lacks the integrity to weather the storms that are inevitable in any relationship. Their judgments about love is mainly self-centeredâhow their partner makes them feel lovedârather than judging themselves over how they might give more to their partner. The attraction is largely externalâlooks, income, statusârather than cherishing the other for his or her good heart and character. Infatuations start up quickly and fade over time. They foster self-absorption within the couple to the exclusion of others.

A simple expedient to separate such self-centered infatuation from genuine love is for the couple to abstain from sexual relations. "Ask the partner to wait until marriage for sex," recommends purity educator Mike Long, "and by their response youâll know if he or she loves you."[21] This is an application of the classic Biblical definition: "Love is patient and kind⊠Love does not insist on its own way" (1 Corinthians 13.3-4).

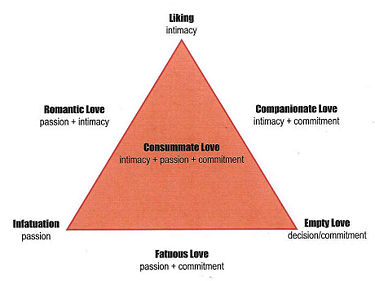

Triangular model of love

A more complete theory of conjugal love has been put forth by psychologist Robert Sternberg, who posits three different components: Intimacy, Passion, and Commitment.

- Intimacyâwhich encompasses the feelings of closeness, connectedness, and bondedness.

- Passionâwhich encompasses the drives that lead to romance, physical attraction, and sexual consummation.

- Commitmentâwhich encompasses, in the short term, the decision that one loves another, and in the long term, the commitment to maintain that love.

Intimacy is a form of love by which two people can share secrets and various details of their personal lives. Intimacy is usually shown in friendships and romantic love affairs. Passion, born of sexual attraction, is shown in infatuation as well as romantic love. Commitment, on the other hand, is the expectation that the relationship is going to last forever.

These three components, pictorially labeled on the vertices of a triangle, interact with each other and with the actions they produce and with the actions that produce them so as to form seven different kinds of love experiences:

intimacy passion commitment Liking or friendship x   Infatuation  x  Empty love   x Romantic love x x  Companionate love x  x Fatuous love  x x Consummate love x x x

The size of the triangle functions to represent the amount of loveâthe bigger the triangle, the greater the love. The shape of the triangle functions to represent the kind of love, which typically varies over the course of the relationship: passion-stage (right-shifted triangle), intimacy-stage (apex-triangle), commitment-stage (left-shifted triangle), typically.

Of the seven varieties of love, consummate love is theorized to be that love associated with the âperfect couple.â Typically, couples will continue to have great sex fifteen years or more into the relationship, they can not imagine themselves happy over the long term with anyone else, they weather their few storms gracefully, and each delight in the relationship with each other.[22]

Biological understandings

Biological models of sexual love support the above psychological theories. Some biologists and anthropologists posit two major drives: Sexual attraction and attachment. Others divide the experience of love into three partly-overlapping stages: Lust, attraction, and attachment. Attraction can be stimulated by the action of pheromones, similar to that found in many species. Attachment between adults is presumed to work on the same principles that lead infants to become attached to their primary caregivers. It involves tolerating the spouse long enough to rear a child.

Studies in neuroscience have indicated that a consistent number of chemicals are present in the brain when people testify to feeling love. More specifically, higher levels of testosterone and estrogen are present during the lustful or sexual phase of a relationship. Dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin are commonly found during the attraction phase of a relationship. Oxytocin and vasopressin seem to be closely linked to long term bonding and relationships characterized by strong attachments.

Lust is the initial passionate sexual desire that promotes mating, and involves the increased release of chemicals such as testosterone and estrogen. These effects rarely last more than a few weeks or months. Attraction is the more individualized and romantic desire for a specific candidate for mating, which develops as commitment to an individual mate forms. As two people fall in love, their brains release chemicals, including dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, which act similar to amphetamines, stimulating the brain's pleasure center and leading to effects such as an increased heart rate, loss of appetite and sleep, and an intense feeling of excitement.[23] The serotonin effects of being in love have a similar chemical appearance to obsessive-compulsive disorder; which could explain why a person in love cannot think of anyone else.[24] Research has indicated that this stage generally lasts from one and a half to three years and studies have found that a protein molecule known as the nerve growth factor (NGF) has high levels when people first fall in love, but these levels return to as they were after one year.[25]

Since the lust and attraction stages are both considered temporary, a third stage is needed to account for long-term relationships. Attachment is the bonding which promotes relationships that last for many years, and even decades. Attachment is generally based on commitments such as marriage and children, or on mutual friendship based on things like shared interests. It has been linked to higher levels of the chemicals oxytocin and vasopressin than short-term relationships have.

The biological perspective views love as an instinctual and physical drive, just like hunger or thirst. Psychological and philosophical perspectives emphasize the mental and spiritual aspects, including feelings and volition. There are elements of truth in all viewsâas the constitution of human physiology works in concert with the mind to make love a holistic and all-encompassing experience.

The myth of "falling in love"

One insidious fallacy pushed upon people from all sides is the myth of âfalling in love:â Only an overwhelming, irresistible attraction springing up spontaneously between two people can lead to true and lasting love between them. The only challenge is to find the right person who arouses this feeling. If later on problems arise and the feeling should wane, this means this was the wrong person after all and the relationship should end.

This misunderstanding neglects the volitional aspect of loving. âWhile it sounds romantic to âfallâ in love, the truth is that we decide who we want to love,â asserts high school relationship educator Charlene Kamper.[26] While it is true that the feeling aspect of loveâas a strong state of likingâis beyond control, the intentional aspectâas a chosen attitude and behaviorâis not. The latter can influence the former. In other words, the decision to love can encourage the feeling of love.[27]

A person of character in a committed relationship will make effort to love whether or not he or she feels loving at the time.[28] This, of course, is the ordinary experience of parents who actively fulfill the duties of love even in the absence of warm feelings, and find their hearts renewed and affection restored. All religious exhortations to love oneâs neighbor and even oneâs adversary are based on the idea of love as a decision. Though everyone wants to be fond of their spouse without effort, just as one would with a friend, the reality is that in both marriage and friendship, love demands a large measure of doing what one does not feel like doing.

Understanding love as involving an act of will brings in the element of choice. This can be a source of freedom and security for youth, who often struggle with fears that certain flaws mean no one can love them or that married love will someday vanish. âIf we fall out of love,â they wonder, âhow can we bring it back?â They can learn it is possible to generate love even when it is not readily flowing. Indeed, if a man and woman have prepared themselves for lasting loveâby the training they received in their own families, by cultivating self-control, and so onâa strong and affectionate connection builds or rebuilds between them that only deepens and strengthens over time.

Since it is not whom one loves that counts as much as how one loves, youth do not have to wait helplessly to bump into the âright person.â They can be getting practice and building confidence in becoming loving persons where they are right now. Furthermore, the notion of love as an active verb helps young people grasp the key difference between maturity and immaturityâthe immature focus on being loved; the mature focus on giving love.

Religious teachings on Love as an ethical and spiritual ideal

Religions lift up those qualities that make for "true love"âlove that helps those experiencing it live fuller lives. These include love for and from God; love within a family, including conjugal love; friendship; love for the community, and general altruism.

In Christianity

The Christian ideal of love is most famously described by Saint Paul:

Love is patient; love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres (1 Corinthians 13:4â7 NIV).

Christianity lifts up the Greek term AgapÄ to describe such love. AgapÄ love is charitable, selfless, altruistic, and unconditional. It is the essence of parental love, ever creating goodness in the world; it is the way God is seen to love humanity. It was because of God's agapÄ love for humanity he sacrificed his Son. John the Apostle wrote, "For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life" (John 3:16 KJV).

Furthermore, agapÄ is the kind of love that Christians aspire to have for others. In the above quote from Saint Paul, he added as the most important virtue of all: "Love never fails" (1 Corinthians 13:8 NIV). Jesus taught, "Love your enemies" (Matthew 5:44, Luke 6:27), in keeping with the character of agapÄ as unconditional love, given without any expectation of return. Loving in this way is incumbent on all Christians, as John the Apostle wrote:

If anyone says, "I love God," and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen, cannot love God whom he has not seen (1 John 4.20).

In Islam

Islam also lifts up the ideal that one should love even one's enemies. A well-known Hadith says, "A man is a true Muslim when no other Muslim has to fear anything from either his tongue or his hand." (Bukhari).

Among the 99 names of God (Allah) are "the Compassionate," "the Merciful," and "the Loving One" (Al-Wadud). God's love is seen as an incentive for sinners to aspire to be as worthy of God's love as they may. All who hold the faith have God's love, but to what degree or effort he has pleased God depends on the individual itself.

This Ishq, or divine love, is a chief emphasis of Sufism. Sufis believe that love is a projection of the essence of God to the universe. God desires to recognize beauty, and as if one looks at a mirror to see oneself, God "looks" at itself within the dynamics of nature. Since everything is a reflection of God, the school of Sufism practices to see the beauty inside the apparently ugly. Sufism is often referred to as the religion of Love. God in Sufism is referred to in three main terms which are the Lover, Loved, and Beloved, with the last of these terms being often seen in Sufi poetry. A common viewpoint of Sufism is that through love, humankind can get back to its inherent purity and grace.

In Judaism

| "And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might." âDeuteronomy 6:5 |

Judaism employs a wide definition of love, both between people and between humans and the Deity. As for the former, the Torah states, "Love your neighbor as yourself" (Leviticus 19:18). As for the latter, one is commanded to love God "with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might" (Deuteronomy 6:5), taken by the Mishnah (a central text of the Jewish oral law) to refer to good deeds, willingness to sacrifice one's life rather than commit certain serious transgressions, willingness to sacrifice all one's possessions, and being grateful to the Lord despite adversity (Berachoth 9:5, Sanhedrin 74a).

The twentieth century rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler is frequently quoted as defining love from the Jewish point of view as "giving without expecting to take" (Michtav me-Eliyahu, vol. I), as can be seen from the Hebrew word for love ahava, as the root of the word is hav, to give.

As for love between marital partners, this is deemed an essential ingredient to life: "See life with the wife you love" (Ecclesiastes 9:9). The Biblical book Song of Songs is a considered a romantically-phrased metaphor of love between God and his people, but in its plain reading reads like a love song. However, romantic love per se has few echoes in Jewish literature.

In Buddhism

Buddhism clearly teaches the rejection of KÄma, sensuous, sexual love. Since it is self-centered, it is an obstacle on the path to enlightenment. Rather, Buddhism advocates these higher forms of love:

- KarunÄ is compassion and mercy, which reduces the suffering of others. It is complementary to wisdom, and is necessary for enlightenment.

- Advesa and maitrī are benevolent love. This love is unconditional and requires considerable self-acceptance. This is quite different from the ordinary love, which is usually about attachment and sex, which rarely occur without self-interest. This ideal of Buddhist love is given from a place of detachment and unselfish interest in others' welfare. The Metta Sutta describes divine love as universal, flowing impartially to all beings:

May all beings be happy and secure, may their hearts be wholesome! Whatever living beings there be: feeble or strong, tall, stout or medium, short, small or large, without exception; seen or unseen, those dwelling far or near, those who are born or those yet unbornâmay all beings be happy!

Let none deceive another, nor despise any person whatsoever in any place. Let him not wish any harm to another out of anger or ill-will. Just as a mother would protect her only child at the risk of her own life, even so, let him cultivate a boundless heart towards all beings. Let his thoughts of boundless love pervade the whole world: above, below, and across without any obstruction, without any hatred, without

any enmity. Whether he stands, walks, sits or lies down, as long as he is awake, he should develop this mindfulness. This, they say, is the noblest living here. (Sutta Nipata 143-151)[29]

- In Tibetan Buddhism, the Bodhisattva ideal involves the complete renunciation of oneself in order to take on the burden of a suffering world. Since even the aspiration for personal salvation can involve a sense of self, the bodhisattva rejects it as an unwholesome state, and instead puts the salvation of others ahead of his own salvation. The strongest motivation to take the path of the Bodhisattva is the limitless sacrificial love of a parent towards her only child, now cultivated to the extent that one can love all beings universally in this way.

In Confucianism

In Confucianism, true love begins with the heart's foundation of benevolence (ren, ä»). The philosopher Zhu Xi regarded ren as a universal principle and the basis for love and harmony among all beings:

Benevolence (ä») is simple undifferentiated gentleness. Its energy is the springtime of the universe, and its principle is the mind of living things in the universe (Zhu Xi).

However, benevolence must be cultivated in actual human relationships. This is lian (æ), the virtuous benevolent love that is cultivated in the family and society. The practice of loving relationships is the sum of the moral life. More than that, it is through participating in these relationships that a person's identity and worth are formed.

The Chinese philosopher Mo-tzu developed a second concept of love, ai (æ), which is universal love towards all beings, not just towards friends or family, and without regard to reciprocation. It is close to the Christian concept of agape love. Confucianism also calls for love for all beings, but sees such social love as an extension of the elements of love learned in the family.

Hinduism

In Hinduism bhakti is a Sanskrit term meaning "loving devotion to the supreme God." Hindu writers, theologians, and philosophers have distinguished nine forms of devotion that they call bhakti. As regards human love, Hinduism distinguishes between kÄma, or sensual, sexual love, with prema, which refers to elevated love. It also speaks of Karuna, compassion and mercy which reduces the suffering of others.

Prema has the ability to melt karma which is also known as the moving force of past actions, intentions, and reactions to experience in life. When people love all things, the force of karma that is in relation to those things, events, or circumstances slowly starts going towards peacefulness, relaxation, and freedom and people find themselves in a "state of love."

Thus, all the major religions agree that the essential characteristic by which true love can be identified is that it focuses not on the needs of the self, but is concerned with those of others. Each adds its unique perspective to this essential truth.

Platonic love

In the fourth century B.C.E., the Greek philosopher Plato posited the view that one would never love a person in that personâs totality, because no person represents goodness or beauty in totality. At a certain level, one does not even love the person at all. Rather, one loves an abstraction or image of the personâs best qualities. Plato never considered that one would love a person for his or her unique qualities, because the ideas are abstractions that do not vary. In love, humanity thus looks for the best embodiment of a universal truth in a person rather than that of an idiosyncratic truth.

Platonic love in its modern popular sense is an affectionate relationship into which the sexual element does not enter, especially in cases where one might easily assume otherwise. A simple example of platonic relationships is a deep, non-sexual friendship between two heterosexual people of the opposite sex.

Ironically, the very eponym of this love, Plato, as well as Socrates and others, belonged to the community of men who engaged in erotic pedagogic friendships with boys. The concept of platonic love thus arose within the context of the debate pitting mundane sexually expressed pederasty against the philosophicâor chasteâpederasty elaborated in Plato's writings. Hence, the modern meaning of Platonic love misunderstands the nature of the Platonic ideal of love, which from its origin was that of a chaste but passionate love, based not on lack of interest but virtuous restraint of sexual desire. This love was meant to bring the lovers closer to wisdom and the Platonic Form of Beauty. It is described in depth in Plato's Phaedrus and Symposium. In the Phaedrus, it is said to be a form of divine madness that is a gift from the gods, and that its proper expression is rewarded by the gods in the afterlife; in the Symposium, the method by which love takes one to the form of beauty and wisdom is detailed.

Plato and his peers did not teach that a man's relationship with a youth should lack an erotic dimension, but rather that the longing for the beauty of the boy is a foundation of the friendship and love between those two. However, having acknowledged that the man's erotic desire for the youth magnetizes and energizes the relationship, they countered that it is wiser for this eros to not be sexually expressed, but instead be redirected into the intellectual and emotional spheres.

Because of its common, modern definition, Platonic love can be seen as paradoxical in light of these philosophers' life experiences and teachings. To resolve this confusion, French scholars found it helpful to distinguish between amour platonique (the concept of non-sexual love) and amour platonicien (love according to Plato). When the term "Platonic love" is used today, it generally does not describe this aspect of Plato's views of love.

Love in culture

Love is one of the most featured themes in all of culture, more than knowledge, money, power, or even life itself. Love is the absolute, eternal desire of all human beings, and as such it is the most popular topic in all the arts. For as long as there have been songs and the written word, there have been works dedicated to love.

The type of love often featured is unrequited love. The first century B.C.E. Roman poet Catullus wrote about his unrequited love for Lesbia (Clodia) in several of his Carmina. Perhaps the most famous example in Western culture of unrequited love is Dante Alighieri for Beatrice. Dante apparently spoke to Beatrice only twice in his life, the first time when he was nine years old and she was eight. Although both went on to marry other people, Dante nevertheless regarded Beatrice as the great love of his life and his "muse." He made her the guide to Heaven in his work, The Divine Comedy. Additionally, all of the examples in Dante's manual for poets, La Vita Nuova, are about his love for Beatrice. The prose which surrounds the examples further tells the story of his lifelong devotion to her.

Shakespeare tackled the topic in his plays, Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Twelfth Night. A more threatening unrequited lover, Roderigo, is shown in Othello.

Unrequited love has been a topic used repeatedly by musicians for decades. Blues artists incorporated it heavily; it is the topic of B.B. King's "Lucille" and "The Thrill is Gone," Ray Charles's "What'd I Say." Eric Clapton's band, Derek and the Dominos devoted a whole album to the topic, Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs. From The Eagles all the way to Led Zeppelin, almost every classic rock band has at least one song on the topic of love.

A theme in much popular music is that of new love, "falling in love:"

- Take my hand, take my whole life too

- For I can't help falling in love with you ("Can't Help Falling in Love" sung by Elvis Presley)

The singers may be anticipating the joy of "endless love" together:

- Two hearts,

- Two hearts that beat as one

- Our lives have just begun. ("Endless Love" by Lionel Ritchie)

These songs reflect the celebration of adolescence in American culture, with its rather shallow and unrealistic view of romantic love. Compared to the tradition of unrequited love, there is little here that speaks to love as a life-long bond, persevering and enduring despite disappointments and hardships.

Notes

- â Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006, ISBN 0061129739).

- â M. Scott Peck, The Road Less Traveled (Simon & Schuster, 1978, ISBN 0671250671).

- â Institute of Human Thermodynamics, Top 150 Definitions of "Love" Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- â Eric H. Erikson, Joan M. Erikson, and Hellen Kivnick, Vital Involvement in Old Age: the Experience of Old Age in Our Time (New York: Norton, 1986), 53.

- â Willard W. Hartup, Having Friends, Making Friends and Keeping Friends: Relationships as Educational Contexts, ERIC Digest, (The Educational Resources Information Center, University of Minnesotaâs Center for Early Education and Development, 1992), 1. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- â Samuel P. Oliner and Pearl M. Oliner, The Altruistic Personality: Rescuers of Jews in Nazi Europe (New York: Free Press, 1988), 171.

- â Linda J. Waite and Maggie Gallagher, The Case for Marriage (New York: Doubleday, 2000).

- â William Blake, âAuguries of Innocence,â from Poems (1863).

- â Martin Luther King, Jr., The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life Delivered at New Covenant Baptist Church, Chicago, Illinois, April 9, 1967. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- â Selma H. Fraiberg, The Magic Years (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1959), 293.

- â Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica (New York: Benziger Bros., 1948).

- â Vladimir Solovyov, The Meaning of Love (Lindisfarne Books, 1995, ISBN 0940262185).

- â Erich Fromm, The Art of Loving (Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006, ISBN 0061129739).

- â Gabriel Moran, Religious Education Development: Images for the Future (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1983), 169.

- â Uichi Shoda, Walter Mischel, and Philip K. Peake, âPredicting Adolescent Cognitive and Self-Regulatory Competencies from Preschool Delay of Gratification,â Developmental Psychology 26/6 (1990): 978-986.

- â R. Travers Herford (ed.), The Ethics of the Talmud: Sayings of the Fathers (New York: Schocken Books, 1925, 1962).

- â Rollo May, Love and Will (New York: Norton, 1969).

- â Lin Yutang, trans., The Wisdom of Confucius (New York: Random House, 1938).

- â Lewis B. Smedes, Sex for Christians (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans), 19.

- â Christopher West, Theology of the Body for Beginners (Wellspring, 2018, ISBN 978-1635820072).

- â Mike Long, âEveryone is NOT Doing It!: Emotional Roller Coaster,â Abstinence Education Video Series, M.L. Productions, 2002.

- â Robert Sternberg, Cupid's Arrow: The Course of Love through Time (Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521478936).

- â Robert Winston, Human (Dorling Kindersley Publishers Ltd., 2004, ISBN 140530233X).

- â Lauren Slater, "Love: The Chemical Reaction," National Geographic (2006).

- â E. Emanuele, P. Polliti, M. Bianchi, P. Minoretti, M. Bertona, and D. Geroldi, Raised plasma nerve growth factor levels associated with early-stage romantic love, Psychoneuroendocrinology, (2005). Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- â Charlene Kamper, Connections: Relationships and Marriage, Teachers Manual (Berkeley, CA: The Dibble Fund for Marital Enhancement, 1996), 35.

- â Lori H. Gordon, Passage to Intimacy (Fireside, 2001, ISBN 978-0671795962).

- â M. Scott Peck, The Road Less Traveled: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values and Spiritual Growth (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 119-120.

- â Andrew Wilson (ed.), True Love World Scripture. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, Roger, Hillar Kilpatrick, and Ed de Moor (eds.). Love and Sexuality in Modern Arabic Literature. London: Saqi Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0863560750

- Bartsch, Shadi, and Thomas Bartscherer (eds). Erotikon: Essays on Eros, Ancient and Modern. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0226038391

- Devine, Tony, Joon Ho Seuk, and Andrew Wilson. Cultivating Heart and Character: Educating for Life's Most Essential Goals. Chapel Hill, NC: Character Development Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1892056151

- Eddy, Baker M. Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. The Christian Science Board of Directors, 2006. ISBN 978-0879523060

- Erikson, Eric H., Joan M. Erikson, and Hellen Kivnick. Vital Involvement in Old Age: the Experience of Old Age in Our Time. W.W. Norton & Company, 1994. ISBN 978-0393312164

- Fisher, Helen. Why We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love. Holt Paperbacks, 2004. ISBN 978-0805077964

- Fraiberg, Selma H. The Magic Years. Scribner, 1996. ISBN 978-0684825502

- Froböse, Gabriele, and Rolf Froböse. Michael Gross (Trans.). Lust and Love: Is it More Than Chemistry? Royal Society of Chemistry, 2006. ISBN 0854048677

- Fromm, Erich. The Art of Loving. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006. ISBN 0061129739

- Gordon, Lori H. Passage to Intimacy. Fireside, 2001. ISBN 978-0671795962

- Herford, R. Travers (ed.). The Ethics of the Talmud: Sayings of the Fathers. Schocken, 1987. ISBN 978-0805200232

- Johnson, Paul. Love, Heterosexuality and Society. Routledge: London, 2005. ISBN 978-0415364850

- Kamper, Charlene. Connections: Relationships and Marriage, Teachers Manual. Berkeley, CA: The Dibble Fund for Marital Enhancement, 1996.

- May, Rollo. Love & Will. W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. ISBN 978-0393330052

- Moran, Gabriel. Religious Education Development: Images for the Future. Winston Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0866836920

- Oliner, Samuel P., and Pearl M. Oliner, The Altruistic Personality: Rescuers of Jews in Nazi Europe. Simon and Schuster, 1992. ISBN 978-0029238295

- Oord, Thomas J. Science of Love: The Wisdom of Well-Being. Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1932031706

- Peck, M. Scott. The Road Less Traveled, 25th Anniversary Edition: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values, and Spiritual Growth. Touchstone, 2003. ISBN 0743243153

- Smedes, Lewis B. Sex for Christians: The Limits and Liberties of Sexual Living. Eerdmans, 1994. ISBN 978-0802807434

- Solovyov, Vladimir. The Meaning of Love. Lindisfarne Books, 1985. ISBN 978-0940262188

- Sternberg, R. J. Cupid's Arrowâthe Course of Love through Time. Cambridge University Press,1998. ISBN 0521478936

- Tennov, Dorothy. Love and Limerence. Scarborough House, 1979. ISBN 0812823281

- Tennov, Dorothy. A Scientist Looks at Romantic Love and Calls It "Limerence": The Collected Works of Dorothy Tennov. Greenwich, CT: The Great American Publishing Society (GRAMPS).

- Waite, Linda J., and Maggie Gallagher. The Case for Marriage. Broadway Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0767906326

- West, Christopher. Theology of the Body for Beginners. Wellspring, 2018. ISBN 978-1635820072

- Winston, Robert. Human : The Definitive Guide to Our Species. Gardners Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1405302333

- Wood, Samuel E., Ellen Green Wood, and Denise Boyd. The World of Psychology. 6th edition. Pearson Education, 2007. ISBN 978-0205499410

External links

All links retrieved March 16, 2025.

- God and Love Beautiful Islam.

- Love: An Anthology Compiled by Yanki Tauber, Chabad.org.

- Unrequited love can be a 'killer' BBC News.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Love history

- Love_(scientific_views)Â history

- Platonic_love history

- Love_(religious_views)Â history

- Love_(cultural_views)Â history

- Unrequited_love history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.