Narcissism

Narcissism is a self-centered personality style characterized as having an excessive preoccupation with oneself and one's own needs, often at the expense of others.

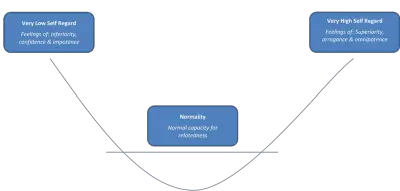

Narcissism can be described as a continuum that ranges from normal to abnormal. A moderate degree of narcissism may be healthy, supporting good self-esteem and feelings of self-worth and thereby the ability to function well in society. However, more extreme forms, such as when people are excessively self-absorbed, or who have a mental illness like narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) where the narcissistic tendency has become pathological, result in functional impairment and psychosocial disability which are detrimental to society.

Historical background

The term narcissism comes from the Roman poet Ovid's Metamorphoses, written in the year 8 B.C.E. Book III of the poem tells the mythical story of a handsome young man, Narcissus, who spurns the advances of many potential lovers. When Narcissus rejects the nymph Echo, who was cursed to only echo the sounds that others made, the gods punish Narcissus by making him fall in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. When Narcissus discovers that the object of his love cannot love him back, he slowly pines away and dies.[1]

The concept of excessive selfishness has been recognized throughout history. Some religious movements such as the Hussites attempted to rectify what they viewed as the shattering and narcissistic cultures of recent centuries.[2]

It was not until the late 1800s that narcissism began to be defined in psychological terms.[3] Since that time, the term has had a significant divergence in meaning in psychology. It has been used to describe:

- a sexual perversion,

- a normal developmental stage,

- a symptom in psychosis, and

- a characteristic in several of the object relations [subtypes].[4]

In 1889, psychiatrists Paul Näcke and Havelock Ellis independently used the term "narcissism" to describe a person who treats their own body in the same way in which the body of a sexual partner is ordinarily treated. Narcissism, in this context, was seen as a perversion that consumed a person's entire sexual life.[3]

In 1911 Otto Rank published the first clinical paper about narcissism, linking it to vanity and self-admiration.[3]

Sigmund Freud (1914) published his theory of narcissism in a lengthy essay titled "On Narcissism: An Introduction." For Freud, narcissism refers to the individual's direction of libidinal energy toward themselves rather than objects and others. He postulated a universal "primary narcissism," that was a phase of sexual development in early infancy ‚Äď a necessary intermediate stage between auto-eroticism and object-love, love for others. Portions of this 'self-love' or ego-libido are, at later stages of development, expressed outwardly, or "given off" toward others. Freud's postulation of a "secondary narcissism" came as a result of his observation of the peculiar nature of the schizophrenic's relation to themselves and the world. He observed that the two fundamental qualities of such patients were megalomania and withdrawal of interest from the real world of people and things: "the libido that has been withdrawn from the external world has been directed to the ego and thus gives rise to an attitude which may be called narcissism."[5] It is a secondary narcissism because it is not a new creation but a magnification of an already existing condition (primary narcissism).

In an essay called "The God-complex," in a collection published in 1923, Ernest Jones described extreme narcissism as a character trait. He described people with the God-complex as being aloof, self-important, overconfident, auto-erotic, inaccessible, self-admiring, and exhibitionistic, with fantasies of omnipotence and omniscience. He observed that these people had a high need for uniqueness.[6]

In 1925, Robert Waelder conceptualized narcissism as a personality trait. His definition described individuals who are condescending, feel superior to others, are preoccupied with admiration, and exhibit a lack of empathy.[7]

In 1939 Karen Horney, a German psychoanalyst of Norwegian and Dutch descent, who was originally a Freudian but later her theories questioned his views, particularly Freud’s theory of human sexuality, postulated that narcissism was on a spectrum that ranged from healthy self-esteem to a pathological state.[8]

Today, narcissism is defined as a self-centered personality style characterized as "excessive self-love or egocentrism" and "in psychoanalytic theory, the taking of one’s own ego or body as a sexual object or focus of the libido or the seeking or choice of another for relational purposes on the basis of his or her similarity to the self." [9] It is also understood as a continuum that ranges from normal to abnormal personality expression.[10]

Characteristics

While many psychologists believe that a moderate degree of narcissism is normal and healthy in humans, there are also more extreme forms, observable particularly in people who are excessively self-absorbed, or who have a mental illness like narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), where the narcissistic tendency has become pathological,[10] leading to functional impairment and psychosocial disability.[11]

Healthy levels

Some psychologists suggest that a moderate level of narcissism is supportive of good psychological health with self-esteem acting as a mediator between narcissism and mental health. Therefore, because of their elevated self-esteem, deriving from self-perceptions of competence and likability, high narcissists are relatively free of worry and gloom.[12] In other words, those who lack self-regard, not experiencing self-love and self-worth, may become dysfunctional in the opposite direction.[3]

Healthy narcissism was first conceptualized by Heinz Kohut, who used the descriptor "normal narcissism" and "normal narcissistic entitlement" to describe children's psychological development. Kohut's research showed that if early narcissistic needs could be adequately met, the individual would move on to what he called a "mature form of positive self-esteem; self-confidence" or healthy narcissism.[13]

In Kohut's tradition, the features of healthy narcissism are:

- Strong self-regard.

- Empathy for others and recognition of their needs.

- Authentic self-concept.

- Self-respect and self-love.

- Courage to abide criticism from others while maintaining positive self-regard.

- Confidence to set and pursue goals and realize one's hopes and dreams.

- Emotional resilience.

- Healthy pride in self and one's accomplishments.

- The ability to admire and be admired.

Anthropologist Ernest Becker, in his Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Denial of Death, argued that healthy narcissism is essential to the sense that a human being has that they have value: "a working level of narcissism is inseparable from self-esteem, from a basic sense of self-worth."[14] In his view:

The child who is well nourished and loved develops, as we said, a sense of magical omnipotence, a sense of his own indestructibility, a feeling of proven power, and secure support. He can imagine himself, deep down, to be eternal. We might say that his repression of the idea of his own death is made easy for him because he is fortified against it in his very narcissistic vitality. ... All too absorbing and relentless to be an aberration; it expresses the heart of the creature: the desire to stand out, to be the one in creation. When you combine natural narcissism with the basic need for self-esteem, you create a creature who has to feel himself an object of primary value: first in the universe, representing in himself all of life.[14]

Destructive levels

While narcissism, in and of itself, can be considered a normal personality trait, high levels of narcissistic behavior can be harmful to both self and others.[13] Destructive narcissism is the constant exhibition of a few of the intense characteristics usually associated with pathological Narcissistic Personality Disorder such as a "pervasive pattern of grandiosity," which is characterized by feelings of entitlement and superiority, arrogant or haughty behaviors, and a generalized lack of empathy and concern for others.[9] On a spectrum, destructive narcissism is more extreme than healthy narcissism but not as extreme as the pathological condition.[15]

Pathological levels

Extremely high levels of narcissistic behavior are considered pathological, a condition termed Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). This pathological condition of narcissism is a magnified, extreme manifestation of healthy narcissism. It is characterized by a life-long pattern of exaggerated feelings of self-importance, an excessive need for admiration, and a diminished ability to empathize with others' feelings, manifesting itself in the inability to love others, emptiness, boredom, and an unremitting need to search for power, while making the person unavailable to others.[13] It is often comorbid with other mental disorders and associated with significant functional impairment and psychosocial disability.[11]

NPD is classified as one of the sub-types of the broader category known as personality disorders.[11][16] Personality disorders are a class of mental disorders characterized by enduring and inflexible maladaptive patterns of behavior, cognition, and inner experience, exhibited across many contexts and deviating from those accepted by any culture. These patterns develop by early adulthood, and are associated with significant distress or impairment.[16][17]

There is no standard treatment for NPD, and its high comorbidity with other mental disorders influences treatment choice and outcomes.[18] Psychotherapeutic treatments generally fall into two categories: psychoanalytic/psychodynamic and Cognitive behavioral therapy, with growing support for integration of both in therapy. However, there is an almost complete lack of studies determining the effectiveness of treatments.[19]

Expressions of narcissism

Primary expressions

Two primary expressions of narcissism have been identified: grandiose ("thick-skinned") and vulnerable ("thin-skinned"). The core of narcissism is posited to be self-centered antagonism (or "entitled self-importance"), namely selfishness, entitlement, lack of empathy, and devaluation of others.[20] Grandiosity and vulnerability are seen as different expressions of this antagonistic core, arising from individual differences in the strength of the approach and avoidance motivational systems.[10]

Grandiose

Narcissistic grandiosity is thought to arise from a combination of the antagonistic core with temperamental boldness‚ÄĒdefined by positive emotionality, social dominance, reward-seeking, and risk-taking. Grandiosity is defined‚ÄĒin addition to antagonism‚ÄĒby a confident, exhibitionistic, and manipulative self-regulatory style:[10]

- High self-esteem and a clear sense of uniqueness and superiority, with fantasies of success and power, and lofty ambitions

- Social potency, marked by exhibitionistic, authoritative, charismatic and self-promoting interpersonal behaviors

- Exploitative, self-serving relational dynamics; short-term relationship transactions defined by manipulation and privileging of personal gain over other benefits of socialization.

Vulnerable

Narcissistic vulnerability is thought to arise from a combination of the antagonistic core with temperamental reactivity‚ÄĒdefined by negative emotionality, social avoidance, passivity and marked proneness to rage. Vulnerability is defined‚ÄĒin addition to antagonism‚ÄĒby a shy, vindictive and needy self-regulatory style:[10]

- Low and contingent self-esteem, unstable and unclear sense of self, and resentment of others' success

- Social withdrawal, resulting from shame, distrust of others' intentions, and concerns over being accepted

- Needy, obsessive relational dynamics; long-term relationship transactions defined by an excessive need for admiration, approval and support, and vengefulness when needs are unmet.

Other expressions

Sexual

Sexual narcissism has been described as an egocentric pattern of sexual behavior that involves an inflated sense of sexual ability or sexual entitlement, sometimes in the form of extramarital affairs. This can be overcompensation for low self-esteem or an inability to sustain true intimacy.[21]

While this behavioral pattern is believed to be more common in men than in women, it occurs in both males and females who compensate for feelings of sexual inadequacy by becoming overly proud or obsessed with their masculinity or femininity.[22]

Parental

Narcissistic parents often see their children as extensions of themselves, and encourage the children to act in ways that support the parents' emotional and self-esteem needs.[23] Due to their vulnerability, children may be significantly affected by this behavior, and to meet their parents' needs they may sacrifice their own wants and feelings.[24] A child subjected to this type of parenting may struggle in adulthood with their intimate relationships. In extreme situations, this parenting style can result in estranged relationships with the children, coupled with feelings of resentment, and in some cases, self-destructive tendencies.[23]

Alternatively, children with narcissistic parents who project an overvalued sense of self-esteem may imitate their behavior and may themselves grow up to be narcissistic.[25]

Workplace

There is a compulsion of some professionals to constantly assert their competence, even when they are wrong. This professional narcissism can lead otherwise capable, and even exceptional, professionals to fall into narcissistic traps:

Most professionals work on cultivating a self that exudes authority, control, knowledge, competence and respectability. It's the narcissist in us all‚ÄĒwe dread appearing stupid or incompetent.[26]

Executives are often provided with potential narcissistic triggers. Inanimate triggers include status symbols like company cars, company-issued smartphone, or prestigious offices with window views; animate triggers include flattery and attention from colleagues and subordinates.[27]

Narcissism has been linked to a range of potential leadership problems ranging from poor motivational skills to risky decision making, and in extreme cases, white-collar crime.[28]

Celebrity

Celebrity narcissism is a form of narcissism that is brought on by wealth, fame, and the other trappings of celebrity. It is triggered and supported by the celebrity-obsessed society. Fans, assistants, and media all play into the idea that the person really is vastly more important than other people, triggering a narcissistic problem that might have been only a tendency, or latent. As a result, they may suffer from unstable relationships, substance abuse, and erratic behavior.

Robert B. Millman, professor of psychiatry at the Weill Cornell Medical College of Cornell University, coined the term "Acquired situational narcissism" to describe this form of narcissism:

What happens to celebrities is that they get so used to people looking at them that they stop looking back at other people. ... The lack of social norms, controls, and of people centering them makes these people believe they're invulnerable.[29]

Normalization

Several commentators have contended that the American populace has become increasingly narcissistic since the end of World War II.[30][31] According to sociologist Charles Derber, people pursue and compete for attention on an unprecedented scale. The profusion of popular literature about "listening" and "managing those who talk constantly about themselves" suggests its pervasiveness in everyday life.[32] The growth of media phenomena such as "reality TV" programs[30] and social media are generating a "new era of public narcissism."[33]

An analysis of popular song lyrics between 1987 and 2007 also supports the contention that American culture has become more narcissistic. There was a growth in the use of first-person singular pronouns, reflecting a greater focus on the self, and also of references to antisocial behavior; during the same period, there was a diminution of words reflecting a focus on others, positive emotions, and social interactions.[34] References to narcissism and self-esteem in American popular print media have experienced vast inflation since the late 1980s. Between 1987 and 2007 direct mentions of self-esteem in leading US newspapers and magazines increased by 4,540 per cent while narcissism, which had been almost non-existent in the press during the 1970s, was referred to over 5,000 times between 2002 and 2007.[35]

Controversies

The term "narcissism" entered the broader social consciousness following the publication of Christopher Lasch's The Culture of Narcissism in 1979.[31] Since then, social media, bloggers, and self-help authors have indiscriminately applied "narcissism" as a label for those who are self-serving and for all domestic abusers.[4][36]

In the professional world as well there has been an increased interest in narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) in recent years. There are areas of substantial debate that surround the subject, including confusions over the classifying of the various types of personality disorder themselves:

It appears that the psychiatric profession can‚Äôt make up its own mind about what disorders exist and how best to treat them. If they were a patient, they would likely be ‚Äúdiagnosed‚ÄĚ with the ‚Äúborderline personality‚ÄĚ label, a disorder noted for its identity confusion, instability, impulsive mood changes, periodic feelings of emptiness, and self-injurious behaviors.[17]

The extent of the controversy was on public display in 2010‚Äď2013 when the committee on personality disorders for the 5th Edition (2013) of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders recommended the removal of Narcissistic Personality from the manual. A contentious three-year debate unfolded in the clinical community with one of the sharpest critics being professor John Gunderson, MD, the person who led the DSM personality disorders committee for the 4th edition of the manual.[37]

Issues which generated greatest controversy include:

- clearly defining the difference between normal and pathological narcissism,

- understanding the role of self-esteem in narcissism,

- reaching a consensus on the classifications and definitions of sub-types such as "grandiose" and "vulnerable dimensions" or variants of these,

- understanding what are the central versus peripheral, primary versus secondary features/characteristics of narcissism,

- determining if there is consensual description,

- agreeing on the etiological factors,

- deciding what field or discipline narcissism should be studied by,

- agreeing on how it should be assessed and measured, and

- agreeing on its representation in textbooks and classification manuals.[38]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Ovid, A.S. Kline (trans.), Metamorphoses Book III Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Thomas A. Fudge, Matthew Spinka, Howard Kaminsky, and the Future of the Medieval Hussites (Lexington Books, 2021, ISBN 978-1793650801).

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Theodore Millon, Carrie M. Millon, Sarah E. Meagher, Seth D. Grossman, and Rowena Ramnath, Personality Disorders in Modern Life (Wiley, 2004, ISBN 978-0471237341).

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (W. W. Norton & Company, 2006, ISBN 978-0393328615).

- ‚ÜĎ Sigmund Freud, On Narcissism: An Introduction (Read & Co. Great Essays, 2014 (original 1914), ISBN 978-1473319899).

- ‚ÜĎ Ernest Jones, Essays In Applied Psycho-Analysis (Hildreth Press, 2007 (original 1923), ISBN 978-1406703382).

- ‚ÜĎ William T. O‚Ä≤Donohue, Katherine A. Fowler, and Scott O. Lilienfeld (eds.), Personality Disorders: Toward the DSM-V (SAGE Publications, Inc, 2007, ISBN 978-1412904223).

- ‚ÜĎ Karen Horney, New Ways in Psychoanalysis (W. W. Norton & Co Inc, 1964 (original 1939), ISBN 0393001326).

- ‚ÜĎ 9.0 9.1 narcissism APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Zlatan Krizan and Anne D. Herlache, The Narcissism Spectrum Model: A Synthetic View of Narcissistic Personality Personality and Social Psychology Review 22(1) (2018): 3‚Äď31. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Eve Caligor, Kenneth N. Levy, and Frank E. Yeomans, Narcissistic personality disorder: diagnostic and clinical challenges The American Journal of Psychiatry 172(5) (2015): 415‚Äď422. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ C. Sedikides, E.A. Rudich, A.P. Gragg, M. Kumashiro, and C.E. Rusbult, Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: self-esteem matters Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87(3) (2004): 400‚Äď416. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Heinz Kohut, The Analysis of the Self: A Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorders (University of Chicago Press, 2009, ISBN 0226450120).

- ‚ÜĎ 14.0 14.1 Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death (Free Press, 1997 (original 1973), ISBN 978-0684832401).

- ‚ÜĎ Nina W. Brown, The Destructive Narcissistic Pattern (Praeger, 1998, ISBN 978-0275960179).

- ‚ÜĎ 16.0 16.1 American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-0890425541).

- ‚ÜĎ 17.0 17.1 Theodore Millon, Disorders of Personality: Introducing a DSM / ICD Spectrum from Normal to Abnormal (Wiley, 2011, ISBN 978-0470040935).

- ‚ÜĎ Paroma Mitra and Dimy Fluyau, Narcissistic Personality Disorder StatPearls (March 13, 2023). Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Ross M. King, Brin F.S. Grenyer, Clint G. Gurtman, and Rita Younan, A clinician's quick guide to evidence-based approaches: Narcissistic personality disorder Clinical Psychologist 24(1) (March 2020): 91-95. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Thomas Widiger (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Personality Disorders (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0199735013)

- ‚ÜĎ D.F. Hurlbert, Sexual narcissism and the abusive male Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 17(4) (1991): 279‚Äď292. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Gerald Schoenewolf, Psychoanalytic Centrism: Collected Papers of a Neoclassical Psychoanalyst (Living Center Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1481155410).

- ‚ÜĎ 23.0 23.1 Alan Rappoport, Co-Narcissism: How We Adapt to Narcissistic Parents The Therapist (2005). Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ James I. Kepner, Body Process: Working With the Body in Psychotherapy (Jossey-Bass Inc Pub, 1993, ISBN 1555425860).

- ‚ÜĎ Eddie Brummelman, Sander Thomaes, Stefanie A. Nelemans, Bram Orobio de Castro, Geertjan Overbeek, and Brad J. Bushman, Origins of narcissism in children Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112(12) (March 2015): 3659‚Äď3662. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ John Banja, Medical Errors and Medical Narcissism (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2004, ISBN 978-0763783617).

- ‚ÜĎ Andrew J. DuBrin, Narcissism in the Workplace: Research, opinion and practice (Edward Elgar Pub, 2012, ISBN 978-1781001356).

- ‚ÜĎ Amy B. Brunell, William A. Gentry, W.K. Campbell, Brian J. Hoffman, Karl W. Kuhnert, and Kenneth G. DeMarree, Leader Emergence: The Case of the Narcissistic Leader Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 34(12) (2008): 1663 - 1676. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Simon Crompton, All About Me: Loving a narcissist (Collins, 2007, ISBN 978-0007247950).

- ‚ÜĎ 30.0 30.1 Polona Curk and Anastasios Gaitanidis (eds.), Narcissism: A Critical Reader (Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-1855754539).

- ‚ÜĎ 31.0 31.1 Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (Warner Books, Incorporated, 1991 (original 1979), ISBN 978-0446321044).

- ‚ÜĎ Charles Derber, The Pursuit of Attention: Power and Ego in Everyday Life (Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0195135490).

- ‚ÜĎ P. David Marshall, Fame's Perpetual Motion M/C Journal 7(5) (November 2004). Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ C. Nathan DeWall, Richard S Pond, Jr., W. Keith Campbell, and Jean M. Twenge, Tuning in to Psychological Change: Linguistic Markers of Psychological Traits and Emotions Over Time in Popular U.S. Song Lyrics Psychology of Aesthetics Creativity and the Arts 5(3) (2011): 200-207. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ W. Keith Campbell and Joshua D. Miller (eds.), The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments (Wiley, 2011, ISBN 978-0470607220).

- ‚ÜĎ Craig Malkin, Why We Need to Stop Throwing the "Narcissist" Label Around Psychology Today (April 12, 2015). Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Charles Zanor, A Fate That Narcissists Will Hate: Being Ignored The New York Times (November 29, 2010). Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Joshua D. Miller, Donald R. Lynam, Courtland S. Hyatt, and W. Keith Campbell, Controversies in Narcissism Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 13 (2017): 291-315. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-0890425541

- Banja, John. Medical Errors and Medical Narcissism. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2004. ISBN 978-0763783617

- Becker, Ernest. The Denial of Death. Free Press, 1997 (original 1973). ISBN 978-0684832401

- Brown, Nina W. The Destructive Narcissistic Pattern. Praeger, 1998. ISBN 978-0275960179

- Campbell, W. Keith, and Joshua D. Miller (eds.). The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments. Wiley, 2011. ISBN 978-0470607220

- Crompton, Simon. All About Me: Loving a narcissist. Collins, 2007. ISBN 978-0007247950

- Curk, Polona, and Anastasios Gaitanidis (eds.). Narcissism: A Critical Reader. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-1855754539

- Derber, Charles. The Pursuit of Attention: Power and Ego in Everyday Life. Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0195135490

- DuBrin, Andrew J. Narcissism in the Workplace: Research, opinion and practice. Edward Elgar Pub, 2012. ISBN 978-1781001356

- Freud, Sigmund. On Narcissism: An Introduction. Read & Co. Great Essays, 2014 (original 1914). ISBN 978-1473319899

- Fudge, Thomas A. Matthew Spinka, Howard Kaminsky, and the Future of the Medieval Hussites. Lexington Books, 2021. ISBN 978-1793650801

- Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. W. W. Norton & Company, 2006. ISBN 978-0393328615

- Horney, Karen. New Ways in Psychoanalysis. (W. W. Norton & Co Inc, 1964 (original 1939). ISBN 0393001326

- Jones, Ernest. Essays In Applied Psycho-Analysis. Hildreth Press, 2007 (original 1923). ISBN 978-1406703382

- Kepner, James I. Body Process: Working With the Body in Psychotherapy. Jossey-Bass Inc Pub, 1993. ISBN 1555425860

- Kohut, Heinz. The Analysis of the Self: A Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorders. University of Chicago Press, 2009. ISBN 0226450120

- Lasch, Christopher. The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. Warner Books, Incorporated, 1991 (original 1979). ISBN 978-0446321044

- Millon, Theodore. Disorders of Personality: Introducing a DSM / ICD Spectrum from Normal to Abnormal. Wiley, 2011. ISBN 978-0470040935

- Millon, Theodore, Carrie M. Millon, Sarah E. Meagher, Seth D. Grossman, and Rowena Ramnath. Personality Disorders in Modern Life. Wiley, 2004. ISBN 978-0471237341

- O′Donohue, William T., Katherine A. Fowler, and Scott O. Lilienfeld (eds.). Personality Disorders: Toward the DSM-V. SAGE Publications, Inc, 2007. ISBN 978-1412904223

- Schoenewolf, Gerald. Psychoanalytic Centrism: Collected Papers of a Neoclassical Psychoanalyst. Living Center Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1481155410

- Widiger, Thomas (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Personality Disorders. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0199735013

External links

All links retrieved June 2, 2025.

- Narcissism Psychology Today

- What the new science of narcissism says about narcissists Psyche

- Narcissism: Symptoms and Signs WebMD

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.