Meditation

Meditation (from the Latin meditatio: "discourse on a subject")[1] describes a large body of psychophysical techniques whose primary aim is the achievement of non-ordinary states of consciousness, typically through the concentration of attention on some object of thought or awareness.[2] Though virtually all religious traditions contain a contemplative element, meditation practice is more often associated with Eastern religions (such as Buddhism, Daoism, and Hinduism), where these practices have been, and continue to be, integral parts of religious life.[3][4][5] As different meditative disciplines encompass a wide range of spiritual and/or psychophysical practices, they tend to engender a variety of responses in practitioners, from profound mental concentration to mental quiescence. The unifying factor, however, at least among religious understandings of the process, is an ever-deepening, intuitive insight into the ultimate nature of reality.[6]

Though meditation is traditionally associated with religious practice (and often with Eastern spirituality), these techniques have become increasingly common in secular Western culture, where the psychiatric and medical establishments are now beginning to acknowledge and explore the beneficial effects of these practices on psychological and physical health.[7] This process can be seen as analogous to the secularization of other religious techniques, such as yoga and tai chi, upon their incorporation into popular culture.

Categories of Meditation Practice

Though there are as many styles of meditation as there are religious and secular traditions that practice them, meditation practices can (in general) be broadly categorized into two groups based upon their respective focal points: those that focus on the gestalt elements of human experience (the "field" or background perception and experience) are referred to as "mindfulness" practices and those that focus on a specific preselected object are called "concentrative" practices. While most techniques can be roughly grouped under one of these rubrics, it should be acknowledged that some practices involve the shifting of focus between the field and an object.[8]

In mindfulness meditation, the meditator sits comfortably and silently, attempting to submerge conscious ideation and maintain an open focus:

â¦shifting freely from one perception to the nextâ¦. No thought, image or sensation is considered an intrusion. The meditator, with a 'no effort' attitude, is asked to remain in the here and now. Using the focus as an 'anchor' ⦠brings the subject constantly back to the present, avoiding cognitive analysis or fantasy regarding the contents of awareness, and increasing tolerance and relaxation of secondary thought processes.[8]

Concentration meditation, on the other hand, requires the participant to hold attention on a particular object (e.g., a repetitive prayer) while minimizing distractions; bringing the mind back to concentrate on the chosen object.

In some traditions, such as Vipassana, mindfulness and concentration are combined.

As meditation primarily entails the creation of a particular mental state, this process can occur with or without additional corporeal activity - including walking meditation, raja yoga, and tantra.[5]

Approaches to Meditation (Religious and Secular)

Bahá'à faith

The Bahá'à Faith teaches that meditation is necessary component of spiritual growth, when practiced alongside obligatory prayer and fasting. To this end, 'Abdu'l-Bahá is quoted as saying:

"Meditation is the key for opening the doors of mysteries to your mind. In that state man abstracts himself: in that state man withdraws himself from all outside objects; in that subjective mood he is immersed in the ocean of spiritual life and can unfold the secrets of things-in-themselves."[9]

Although the Founder of the Faith, Bahá'u'lláh, never specified any particular forms of meditation, some Bahá'à practices are meditative. One of these is the daily repetition of the Arabic phrase Alláhu Abhá (Arabic: اÙÙ٠ابÙÙ) (God is Most Glorious) 95 times preceded by ablutions. Abhá has the same root as Bahá' (Arabic: بÙاءâ "splendor" or "glory"), which Bahá'Ãs consider to be the "Greatest Name of God."

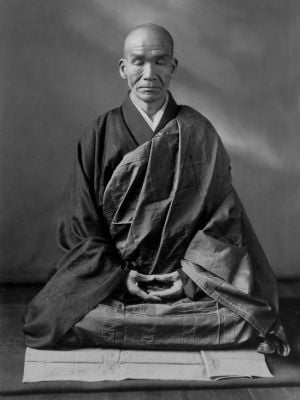

Buddhism

The cultivation of "correct" mental states has always been an important element of Buddhist practice, as canonized in the mental discipline section of the Noble Eightfold Path. The centrality of meditation can be tied to the tradition's founding myth, which describes the historical Buddha attaining enlightenment while meditating under a Bodhi tree. Thus, the majority of early Buddhist teaching revolves around the achievement of particular mystical states as the key to accurate perception of the material world and eventual release from the cycle of samsara (nirvana).

To this end, most forms of Buddhism distinguish between two classes of meditation practices, shamatha and vipassana, both of which were thought to be necessary for attaining enlightenment. The former consists of practices aimed at developing the ability to focus the attention single-pointedly; the latter includes practices aimed at developing insight and wisdom through seeing the true nature of reality. The differentiation between the two types of meditation practices is not always clear cut, which is made obvious when studying practices such as Anapanasati, which could be said to start off as a shamatha practice but that goes through a number of stages and ends up as a vipassana practice.

Theravada Buddhism emphasizes the meditative development of mindfulness (sati)[10] and concentration (samadhi) in the pursuit of Nibbana (Nirvana). Popular subjects in traditional meditation practice include the breath (anapana), objects of repulsion (corpses, excrescences, etc.) and loving-kindness (mettÄ).

In Japanese Mahayana schools, Tendai (Tien-tai), concentration is cultivated through highly structured ritual. Especially in the Chinese Chán Buddhism school (which branched out into the Japanese Zen, and Korean Seon schools), ts'o ch'an meditation and koan meditation practices are understood to allow a practitioner to directly experience the true nature of reality. This focus is even attested to in the names of each of these schools, which are derived from the Sanskrit dhyana, and can thus be translated into "meditation" in their respective languages).

Tibetan Buddhism (Vajrayana) emphasizes the path of tantra for its senior practitioners. Many monks go through their day without "meditating" in a recognizable form, though they are more likely to chant or participate in group liturgy. In this tradition, the purpose of meditation is to awaken the incisive, diamond-like nature of mind and to introduce practitioners to the unchanging, pure awareness that is seen to underlie the whole of life and death.[11]

The gift of learning to meditate is the greatest gift you can give yourself in this life. For it is only through meditation that you can undertake the journey to discover your true nature, and so find the stability and confidence you will need to live, and die, well. Meditation is the road to enlightenment.- Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying.[11]

Though meditation is a vital component of Buddhist practice, it is only one segment of the three types of training required for the attainment of enlightenment, as each adherent is expected to strive for excellence in virtue (sÄ«la), meditation (citta), and wisdom (paññÄ). [12] Thus, meditative prowess alone is not sufficient; it is but one part of the path. In other words, in Buddhism, in tandem with mental cultivation, ethical development and wise understanding are also necessary for the attainment of the highest goal.

Christianity

- See also: Hesychasm

While the world's Christian traditions do contain various practices which might be identified as forms of "meditation," many of them were historically identified as monastic practices. For instance, some types of prayer, such as the rosary and Adoration (focusing on the eucharist) in Roman Catholicism or the hesychasm in Eastern Orthodoxy, may be compared to forms of Eastern meditation that focus on an individual object. Though Christian prayer is often an intellectual (rather than intuitive) exercise, certain practices that encourage the contemplation of the divine mysteries could likewise be seen as meditations. More specifically, the practices recommended in the Philokalia, which stress prayer/meditation as an "attitude of the heart," are more stereotypically meditative, as they involve acquiring an inner stillness and ignoring the physical senses. While these types of (often mystical) meditation were relatively influential during the history of Christianity (as can be seen in the lives and writings of Thomas Merton, Teresa of Avila, and the Quakers, among others), many conservative Christians view meditation with some trepidation, seeing it as an alien and potentially iniquitous force.[13]

Also, Christian sects often use the term meditation in a more intellectual (rather than intuitive) sense to describe the active practice of reflection on some particular theme, such as "meditation on the sufferings of Christ." A similar "intellectualist" understanding of meditation also underlies the evangelical notion of biblical study, one which is often justified by quoting the Book of Joshua:

- Do not let this Book of the Law depart from your mouth; meditate on it day and night, so that you may be careful to do everything written in it, then you will be prosperous and successful (Joshua 1:8).

Daoism

The wide and variegated schools of Daoism include a number of meditative and contemplative traditions. Originally said to have emerged from the I Ching, Dao De Jing, Zhuangzi, and Baopuzi (among other texts), many indigenous Chinese practices have been concerned with the utilization of breath control and physical exercises for the promotion of health, well-being, and longevity. These practices enjoyed a period of fruitful cross-fertilization with Chinese Buddhism, especially the Ch'an (Zen) school.[14]

Such techniques have had significant influence on traditional Chinese medicine and the Chinese, as well as some Japanese martial arts. Most specifically, the Chinese martial art T'ai Chi Ch'uan is based on the Daoist and Neo-Confucian cosmology contained in the Taijitu ("Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate"), which correlates individual actions with their macrocosmic functioning of the universe. Many Daoist martial arts are thought of as "moving meditations," such that the practical ideal is "stillness in movement."

Hinduism

Hinduism is the oldest religion in the world that professes meditation as a spiritual and religious practice. Archaeologists have discovered carved images of figures who appear to be practicing meditation at ancient Indian archaeological sites.

Several forms of meditation have developed in Hinduism, which are closely associated with the practice of Yoga as a means to both physiological and spiritual mastery. Among these types of meditation include Jnana Yoga, Surat shabd yoga, ("sound and light meditation"), Japa Yoga, in (repetition of a mantra), Bhakti Yoga (the yoga of love and devotion), Hatha Yoga, in which postures and meditations are aimed at raising the spiritual energy, and Raja Yoga (Devanagari: यà¥à¤), one of the six schools of Hindu philosophy, focusing on meditation.

Raja Yoga as outlined by Patanjali, which describes eight "limbs" of spiritual practices, half of which might be classified as meditation. Underlying them is the assumption that a yogi should still the fluctuations of his or her mind: Yoga cittavrrti nirodha.

Additionally, the Hindu deities are often depicted as practicing meditation, especially Shiva.

Islam

In Islam, meditation serves as the core element of various mystical traditions (in particular Sufism), though it is also thought to promote healing and creativity in general.[15] The Muslim prophet Muhammad, whose deeds provide a moral example for devout Muslims, spent long periods in meditation and contemplation. Indeed, the tradition holds that it was during one such period of meditation that Muhammad began to receive revelations of the Qur'an.[16]

There are two concepts or schools of meditation in Islam:

- Tafakkur and Tadabbur, which literally refers to "reflection upon the universe." Muslims feel this process, which consists of quiet contemplation and prayer, will allow the reception of divine inspiration that awakens and liberates the human mind. This is consistent with the global teachings of Islam, which view life as a test of the adherent's submission to Allah. This type of meditation is practiced by Muslims during the second stage of the Hajj, during their six to eight hour sojourn at Mount Arafat.[17]

- The second form of meditation is Sufi meditation, which is largely based on mystical exercises. These exercises consist of practices similar to Buddhist meditation, known as Muraqaba or Tamarkozâterms that denote âconcentration,â referring to the âconcentration of abilities.â Consequently, the term "muraqaba" suggests to close attention, and the convergence and consolidation of mental faculties through meditation. Gerhard Böwering provides a clear synopsis of the mystical goal of Sufi meditation:

Through a distinct meditational technique, known as dikr, recollection of God, the mystics return to their primeval origin on the Day of Covenant, when all of humanity (symbolically enshrined in their prophetical ancestors as light particles or seeds) swore an oath of allegiance and witness to Allah as the one and only Lord. Breaking through to eternity, the mystics relive their waqt, their primeval moment with God, here and now, in the instant of ecstasy, even as they anticipate their ultimate destiny. Sufi meditation captures time by drawing eternity from its edges in pre- and post-existence into the moment of mystical experience.[18]

However, it should be noted that the meditation practices enjoined by the Sufis are controversial among Muslim scholars. Though one group of Ulama, most namely Al-Ghazzali, have accepted such practices as spiritually valid, more conservative thinkers (such as Ibn Taymiya) have rejected them as bid'ah (Arabic: بدعةâ) (religious innovation).

Jainism

For Jains, meditation practices are described as samayika, a word in the Prakrit language derived from samay ("time"). The aim of Samayika is to transcend the daily experiences of being a "constantly changing" human being, Jiva, and allow for the identification with the "changeless" reality in the practitioner, the Atma. The practice of samayika begins by achieving a balance in time. If the present moment of time is taken to be a point between the past and the future, Samayika means being fully aware, alert and conscious in that very moment, experiencing one's true nature, Atma, which is considered common to all living beings. In this, samayika can be seen as a "mindfulness" practice par excellence (as described above).

In addition to these commonly accepted meditation techniques, others are accepted only in certain sects. For instance, a practice called preksha meditation is said to have been rediscovered by the 10th Head of Jain Swetamber Terapanth sect Acharya Mahaprajna, which consists of concentration upon the perception of the breath, body, and the psychic centers. It is understood that correct application of these techniques will initiate the process of personal transformation, which aims at attaining and purify the deeper levels of existence.[19]

Judaism

- See also: Baal Shem Tov , Hassidism , Kabbala , and Zohar

Though lacking the central focus on meditation found in some eastern religions, there is evidence that Judaism has a longstanding tradition of meditation and meditative practicesâperhaps hearkening back to the Biblical period.[20] For instance, many rabbinical commentators suggest that, when the patriarch Isaac is described as going "×ש××" (lasuach) in the field, he is actually taking part in some type of meditative practice (Genesis 24:63). Similarly, there are indications throughout the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) that meditation was central to the prophets.[20]

In modern Jewish practice, one of the best known meditative practices is called hitbodedut (×ת×××××ת) or hisbodedus, which is explained in both Kabbalistic and Hassidic philosophy. The word hisbodedut, which is derived from the Hebrew word ×××× ("boded" - the state of being alone), refers to the silent, intuitive, personal contemplation of the Divine. This technique was especially central to the spiritual teachings of Rebbe Nachman.[21]

Kabbala, Judaism's best known mystical tradition, also places considerable emphasis on meditative practices. Kabbalistic meditation is often a deeply visionary process, based on the envisioning of various significant cosmic phenomena (including the emanations of G-d (Sefirot), the ultimate Unity (Ein Sof), and the Divine Chariot (Merkabah)).

New Age

New Age meditations are often ostensibly grounded in Eastern philosophy and mysticism such as Yoga, Hinduism, and Buddhism, though they are typically equally influenced by the social mores and material affluence of Western culture. The popularity of meditation in the mainstream West is largely attributable to the hippie-counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, when many of the day's youth rebelled against traditional belief systems.

Some examples of practices whose popularity can be largely tied to the New Age movement include:

- Kriya Yoga - taught by Paramahansa Yogananda in order to help people achieve "self-realization";

- Passage Meditation - a modern method developed by spiritual teacher Eknath Easwaran, which involves silent, focused repetition of memorized passages from world scripture and the writings of great mystics;

- Transcendental Meditation, a form of meditation taught and promoted by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi;

- FISU (Foundation for International Spiritual Unfoldment) - a movement established by Gururaj Ananda Yogi's prime disciples Rajesh Ananda and Jasmini Ananda.

- Ananda Marga meditation - a teaching propounded by a Mahakaula Guru Shrii Shrii Anandamurtiiji in India, who said that it revived sacred practices taught by SadaShiva and Sri Krs'na. His system of meditation, he said, is based on original Tantra as given by Shiva and has sometimes been referred as "Rajadhiraja Yoga." He revised many yogic and meditative practices and introduced some new techniques.

Secular

In addition to the various forms of religious meditation, the modern era has also seen the development of many "consciousness-expanding" movements, many of which are devoid of mystical content and are singularly devoted to promoting physical and mental well being. Some of these include:

- Jacobson's Progressive Muscle Relaxation, which was developed by American physician Edmund Jacobson in the early 1920s. Jacobson argued that since muscular tension accompanies anxiety, one can reduce anxiety by learning how to dissipate muscular tension.

- Autogenic training, which was developed by the German psychiatrist Johannes Schultz in 1932. Schultz emphasized parallels to techniques in yoga and meditation, though he attempted to guarantee that autogenic training would be devoid of any mystical elements.

- The method of Dr. Ainslie Meares, an Australian psychiatrist who explored the effects of meditation in a groundbreaking work entitled Relief Without Drugs (1970). In this text, he recommended some simple, secular relaxation techniques based on Hindu practices as a means of combating anxiety, stress and chronic physical pain.

- Shambhala Training, which was founded in Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche in 1976. This regimen was a secular program of meditation with a belief in basic goodness, with teachings that stressed the path of bravery and gentleness. The 1984 book Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior contains student-edited versions of Trungpa's lectures and writings.

Sikhism

In Sikhism, the practices of simran and NÄm JapÅ, which enjoin the focusing one's attention on the attributes of God, both encourage quiet meditation. The centrality of meditational practices is highlighted by their place in the Guru Granth Sahib, which states:

- Meditating on the Glories of the Lord, the heart-lotus blossoms radiantly.

- Remembering the Lord in meditation, all fears are dispelled.

- Perfect is that intellect, by which the Glorious Praises of the Lord are sung (GaÂoá¹Ä« mehlÄ 5).[22]

Sikhs believe that there are ten 'gates' to the body, 'gates' is another word for 'chakras' or energy centers. The top most energy level is the called the tenth gate or dasam dwar. It is said that when one reaches this stage through continuous practice meditation becomes a habit that continues whilst walking, talking, eating, awake and even sleeping. There is a distinct taste or flavor when a meditator reaches this lofty stage of meditation, as one experiences absolute peace and tranquility inside and outside the body.

Followers of the Sikh religion also believe that love comes through meditation on the lord's name since meditation only conjures up positive emotions in oneself which are portrayed through our actions. The first Guru of the Sikhs, Guru Nanak Dev Ji preached the equality of all humankind and stressed the importance of living a householders life instead of wandering around jungles meditating, as was popular practice at the time. The Guru preached that we can obtain liberation from life and death by living a totally normal family life and by spreading love amongst every human being regardless of religion.

Clinical Studies and Health-Care Applications

Though western medicine is often characterized by a mechanistic understanding of human bodies and physiological processes, many recent medical advances (in fields as disparate as psychology, neurobiology, and palliative care) are predicated on a more holistic approach to the needs of patients. One major advance has been in the acknowledgment of meditation as an effective technique for modifying mental states, improving outlook, regulating autonomic bodily processes, and managing pain.[23]

Meditation, as it is understood in these studies, refers to any practices that aim to inculcate the following psycho-behavioral components:

- relaxation,

- concentration,

- altered state of awareness,

- suspension of logical thought processes, and

- maintenance of self-observing attitude.[24]

In keeping with this more holistic understanding of the human body, the medical community has supported numerous studies that explore the physiological effects of meditation.[25][26][27] One of the more "high-profile" of these was conducted by Dr. James Austin, a neurophysiologist at the University of Colorado, who discovered that Zen meditation rewires the circuitry of the brain[28] â a seemingly counter-intuitive finding that has since been confirmed using functional MRI imaging.[29]

Likewise, Dr. Herbert Benson of the Mind-Body Medical Institute, which is affiliated with Harvard University and several Boston hospitals, reports that meditation induces a host of biochemical and physical changes in the body collectively referred to as the "relaxation response."[27] The relaxation response includes changes in metabolism, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and brain chemistry. These results have been borne out by extensive research into the positive physiological impact of meditation on various bodily processes, including balance,[30] blood pressure,[31] and metabolism,[32] as well as cardiovascular[33] and respiratory function.[34] For example, in an early study in 1972, Transcendental Meditation was shown to affect the human metabolism by lowering the biochemical byproducts of stress, such as lactic acid, decreasing heart rate and blood pressure, and inducing favorable patterns of brain waves.[35] These physiological effects have also demonstrated the efficacy of meditation as part of a treatment regimen for epilepsy.[36]

Given these findings, meditation has entered the mainstream of health care as a method of stress management and pain reduction.[37] As a method of stress reduction, meditation is often used in hospitals in cases of chronic or terminal illness, as it has been found to reduce complications associated with increased stress, such as a depressed immune system.[38] Similar conclusions have been reached by Jon Kabat-Zinn and his colleagues at the University of Massachusetts, who have studied the beneficial effects of mindfulness meditation on stress and outlook.[39][40]

These programs correspond to a growing consensus in the medical community that mental factors such as stress significantly contribute to a lack of physical health, which has led to a growing movement in mainstream science to fund research in this area (e.g. the National Institutes of Health's establishment of five research centers to explore the mind-body elements of disease.)

Notes

- â As noted in the Online Etymology Dictionary, the use of the term "meditation" to describe the process of quiet contemplation is a later linguistic development (ca. 1400 C.E.), with previous usage pertaining to the discursive exploration of a subject. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- â For instance, some medical researchers, requiring an explicit definition of meditation, described it as follows: "self-regulation of attention, in the service of self-inquiry, in the here and now." A. Maison et al. "Meditation, melatonin and breast/prostate cancer: hypothesis and preliminary data," Medical Hypotheses 44 (1) (1995): 39-46.

- â Ramnarayan (R.N.) Vyas, The Bhagavad-Git' and Jivana Yoga (Abhinav Publications, 2003, ISBN 8170172039).

- â Mikel Burley, Hatha Yoga: Its Context, Theory and Practice (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2000, ISBN 8120817052).

- â 5.0 5.1 Heinrich Dumoulin, James W. Heisig, and Paul F. Knitter, Zen Buddhism: A History (India and China) (World Wisdom, 2005, ISBN 0941532895).

- â It should be noted that this mystical insight tends to be described in similar terms, regardless of whether it is understood theistically (as in Christian and Islamic meditation) or non-theistically (as in Buddhist meditation).

- â C. Tart, "Adapting Eastern spiritual teachings to Western culture." The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 22: 149-166.

- â 8.0 8.1 Alberto Perez-De-Albeniz and Jeremy Holmes, "Meditation: Concepts, Effects And Uses In Therapy." International Journal of Psychotherapy 5(1) (March 2000): 49.

- â `Abdu'l-Bahá, Paris Talks. (Bahá'à Distribution Service, (1912) 1995, ISBN 1870989570), 175.

- â As described in the Satipatthana Sutta. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- â 11.0 11.1 Rinpoche Sogyal, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Patrick Gaffney and Andrew Harvey eds. (New York: Harper Collins, 1994).

- â For instance, from the Pali Canon, see MN 44 (Thanissaro, 1998a) and AN 3:88 (Thanissaro, 1998b). Retrieved July 12, 2021. In Mahayana tradition, the Lotus Sutra lists the Six Perfections (paramita) which echoes the threefold training with the inclusion of virtue (ÅÄ«la), concentration (dhyÄna) and wisdom (prajñÄ).

- â See, for example, the critique and denouncement of yoga and meditation in Douglas Groothius' "Dangerous Meditations," Christianity Today 48:11 (November 2004), which argues that "no amount of chanting, visualizing, or physical contortions will melt away the sin that separates us from the Lord - however "peaceful" these practices may feel." This account stresses both the view of human beings as ontologically "Fallen" and the traditional Christian distrust of all non-intellectual forms of rationality.

- â Livia Kohn and Yoshinobu Sakade, Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1989).

- â Kedar Nath Dwivedi, "Review:Freedom from Self, Sufism, Meditation and Psychotherapy." Group Analysis 22 (4) (December 1989): 434-436.

- â S.A. Nigosian, Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004), 8, 15.

- â Nigosian, 111.

- â Gerhard Böwering, "The Concept of Time in Islam," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 141(1) (March 1997): 55-66.

- â Jain Vishwa Bharati, Preksha Meditation Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- â 20.0 20.1 Rami Shapiro, Brief Introduction to Jewish Meditation Judaism, Meditation and Yoga. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- â Ozer Bergman, Where Earth and Heaven Kiss: A Guide to Rebbe Nachman's Path of Meditation (Breslov Research Institute, 2006, ISBN 978-11928822080).

- â Guru Granth Sahib (English translation) Khalis Foundation. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- â L. Shauna, E. R. Shapiro, Gary Schwartz, Craig Santerre, "Meditation and Positive Psychology" in Handbook of Positive Psychology, edited by C.R. Snyder and Shane J. Lopez, (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 632-645.

- â Alberto Perez-De-Albeniz and Jeremy Holmes, Meditation: concepts, effects and uses in therapy International Journal of Psychotherapy 5(1) (Mar 2000): 49-59. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- â S. Venkatesh, T.R. Raju, Y. Shivani, G. Tompkins, B.L. Meti, "A study of structure of phenomenology of consciousness in meditative and non-meditative states" Indian J Physiol Pharmacol (Apr 1997) 41(2): 149â153.

- â C.K. Peng, et al., "Exaggerated heart rate oscillations during two meditation techniques" Int J Cardiol. 70(2) (Jul 31, 1999): 101â107.

- â 27.0 27.1 S.W. Lazar, et al., "Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation" NeuroReport 11(7) (May 15, 2000): 1581â1585

- â James H. Austin, Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998).

- â Mark Kaufman, Meditation Gives Brain a Charge, Study Finds The Washington Post Company, January 3, 2005. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- â Y. Yang et al., "Effect of combined Taiji and Qigong training on balance mechanisms: a randomized controlled trial of older adults," Medical Science Monitor 13(8) (Aug 2007):CR339-348.

- â J.P. Manikonda et al., "Contemplative meditation reduces ambulatory blood pressure and stress-induced hypertension: a randomized pilot trial," Journal of Human Hypertension (Sep 6, 2007).

- â M.S. Chaya, A.V. Kurpad, H.R. Nagendra, and R. Nagarathna, "The effect of long term combined yoga practice on the basal metabolic rate of healthy adults," BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 6 (Aug 31, 2006):28.

- â M. Hill, R. Weber, and S. Werner, "The heart-mind connection," Behavioral Healthcare 26(9) (Sep 2006):30-32.

- â D. Cysarz and A. Büssing, "Cardiorespiratory synchronization during Zen meditation," European Journal of Applied Physiology 95(1) (Sep 2005):88-95.

- â H. Benson and R.K. Wallace, "The Physiology of Meditation" Scientific American 226(2) (1972): 84-90.

- â N. Yardi, "Yoga for control of epilepsy," Seizure 10(1) (Jan 2001):7-12.

- â N.E. Morone and C.M. Greco, "Mind-body interventions for chronic pain in older adults: a structured review," Pain Medicine 8(4) (May-Jun 2007):359-375.

- â L.E. Carlson, Z. Ursuliak, E. Goodey, M. Angen, and M. Speca, "The effects of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients: 6-month follow-up." Support Care Cancer 9(2) (Mar 2001):112-123.

- â Jon Kabat-Zinn, L. Lipworth, and R. Burney, "The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain." Journal of Behavioral Medicine 8(2) (1985): 163-190.

- â Richard J. Davidson et al., "Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation." Psychosomatic Medicine 65(4) (Jul-Aug 2003): 564-570.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

- Austin, James H. Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. ISBN 0262511096.

- Azeemi, Khawaja Shamsuddin Azeemi. Muraqaba: The Art and Science of Sufi Meditation. Houston: Plato, 2005. ISBN 0975887548.

- Bennett-Goleman, T. Emotional Alchemy: How the Mind Can Heal the Heart. Harmony Books, ISBN 0609607529.

- Benson, Herbert, and Miriam Z. Klipper. The Relaxation Response, Expanded Updated ed. Harper, 2000. ISBN 0380815958.

- Bergman, Ozer. Where Earth and Heaven Kiss: A Guide to Rebbe Nachman's Path of Meditation. Breslov Research Institute, 2006. ISBN 978-1928822080.

- Burley, Mikel. Hatha Yoga: Its Context, Theory and Practice. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2000. ISBN 8120817052.

- Dumoulin, Heinrich, James W. Heisig, and Paul F. Knitter. Zen Buddhism: A History (India and China). World Wisdom, 2005. ISBN 0941532895.

- Hayes, S.C., K.D. Strosahl, and K.G. Wilson. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York: Guilford Press, 1999. ISBN 1572309555.

- Kohn, Livia, ed., and Yoshinobu Sakade. Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1989. ISBN 0892640855.

- Lazar, Sara W. "Mindfulness Research." In: Mindfulness and Psychotherapy. C. Germer, R.D. Siegel, P. Fulton, eds. New York: Guildford Press, 2005.

- Metzner R. "Psychedelic, Psychoactive and Addictive Drugs and States of Consciousness." In Mind-Altering Drugs: The Science of Subjective Experience, Chap. 2. Mitch Earlywine, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0195165314.

- MirAhmadi, As Sayed Nurjan. Healing Power of Sufi Meditation The Healing Power of Sufi Meditation. Islamic Supreme Council of America, 2005. (in English)

- Nigosian, S. A. Islam. Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004. ISBN 0253216273.

- Sogyal, Rinpoche. The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Patrick Gaffney and Andrew Harvey eds. New York: Harper Collins, 1994. ISBN 0062508342.

- Tart, Charles T., ed. Altered States of Consciousness, 3rd ed. Harper, 1990. ISBN 0471845604.

- Trungpa, C. Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism. Boston: Shambhala South Asia Editions, 1973.

- Trungpa, C. Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior. Boston: Shambhala Dragon Editions, 1984.

- Vogel, Erhard. Journey Into Your Center. Nataraja Publications, 2001. ISBN 1892484056.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.