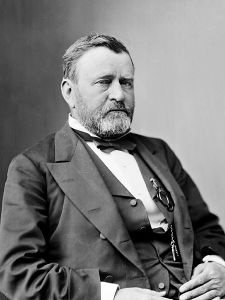

Grant, Ulysses S.

Eric Olsen (talk | contribs) (→Legacy) |

Eric Olsen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

Grant married [[Julia Boggs Dent]] (1826–1902) on August 22, 1848. They had four children: [[Frederick Dent Grant]], [[Ulysses S. (Buck) Grant, Jr.]], [[Ellen (Nellie) Grant]], and [[Jesse Root Grant]]. | Grant married [[Julia Boggs Dent]] (1826–1902) on August 22, 1848. They had four children: [[Frederick Dent Grant]], [[Ulysses S. (Buck) Grant, Jr.]], [[Ellen (Nellie) Grant]], and [[Jesse Root Grant]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Grant was an uncommonly responsible and devoted father and husband, by some estimates "the most ethical and moral family man and U. S. President that we ever had."<ref></ref> He was extremely loving and kind towards his wife and children and was always considered a hero in the eyes of his family. Perhaps General Grant was the . The recollection that his wife, children and grandchildren had of him was of the highest caliber. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Grant was an uncommonly devoted parent and expressed his affection for his children in his letters and in his actions. In an era when most fathers physically manhandled their children, he was lenient to a fault. He particularly spoiled his two youngest children, Nellie and Jesse, and they were his special favorites. Horace Porter, one of Grant's staff officers, recalled, "the children often romped with him and he joined in their frolics as if they were all playmates together. The younger ones would hang around his neck while he was writing, make a terrible mess of the papers, and turn everything in his tent into a toy." | ||

| + | |||

| + | The General's wife, Julia, had no illusions about who was the true disciplinarian in the family. She recalled, "The General had no idea of the government of the children. He would have allowed them to do pretty much as they pleased (hunt, fish, swim, etc.) provided it did not interfere with any duty, but his word was law always. Whenever they were inclined to disobey or question my authority, I would ask the General to speak to them. He would, smiling at me, and say to them, 'Come, come Fred, or Nell, you must not quarrel with Mama. She knows what is best for you and you must always obey her.'" | ||

==Military career== | ==Military career== | ||

Revision as of 17:02, 3 July 2008

| Term of office | March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1877 |

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Date of birth | April 27, 1822 |

| Place of birth | Point Pleasant, Ohio |

| Date of death | July 23, 1885 |

| Place of death | Mount McGregor, New York |

| Spouse | Julia Grant |

| Political party | Republican |

Ulysses S. Grant (April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885) was the commanding general of the combined Union armies during the American Civil War and the eighteenth President of the United States. Grant has been described by military historian J. F. C. Fuller as "the greatest general of his age and one of the greatest strategists of any age." He won many important battles in the western theater, including Vicksburg and Shiloh, and is credited with defeating the Confederacy through a campaign of attrition.

Grant's tenacity in war was matched by his magnanimity in victory. Called to Washington to assume command of the Union armies after his spectacular campaign at Vicksburg in 1863, Grant was hailed as a hero and urged to run for president in in the 1864 election. But Grant summarily turned aside these appeals and affirmed his commitment to President Abraham Lincoln's leadership and military objectives.

Trusted by Lincoln, who suffered through a series of inept and insubordinate generals, Grant shared the president's hatred of slavery; his determination to preserve the Union and, in the process, extirpate slavery; and, importantly, his commitment to reconcile North and South without punitive measures after the fratricidal war. Forever contrasted with aristocratic Confederate General Robert E. Lee, the slovenly dressed, cigar-chomping Grant offered generous terms to his nemesis at the surrender of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, Virginia, in April 1865—allowing Confederate soldiers to return home after swearing allegiance to the United States.

As president, many historians consider him less successful: he led an Administration plagued by scandal, although Grant was not personally tainted by charges of corruption. At the same time Grant governed during the contentious period of Reconstruction of the South, struggled to preserve the Reconstruction, and took an unpopular stand in favor of the legal and voting rights of former slaves.

Grant was respected during his lifetime both in the North and South, and he avoided all perception of retribution upon the Southern states. Historians agree that Grant's leadership as president, although flawed, led the Federal government on a path that might otherwise have provoked an insurgency. Grant's memoirs, composed during terminal illness and under financial necessity, are regarded as among the most eloquent and illuminating writings of a military leader.

Birth and early years

Grant was born Hiram Ulysses Grant in Point Pleasant, Clermont County, Ohio to Jesse Root Grant and Hannah Simpson. In the fall of 1823 they moved to the village of Georgetown in Brown County, Ohio, where Grant spent most of his time until he was 17 years old.

When he was 17 years old, and having barely passed West Point's height requirement for entrance, Grant received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, through his Congressman, Thomas L. Hamer. Hamer erroneously nominated him as Ulysses Simpson Grant, and although Grant protested the change, he bent to the bureaucracy. Upon graduation, Grant adopted the form of his new name using the middle initial only, never acknowledging that the "S" stood for Simpson. He graduated from West Point in 1843, ranking 21st in a class of 39. At the academy, he established a reputation as a fearless and expert horseman. Grant became well known for his use of distilled liquor and, during the American Civil War, began smoking great numbers of cigars (one report is he went through more than 10,000 cigars over the course of five years) which well may have contributed to his developing throat cancer.

Grant married Julia Boggs Dent (1826–1902) on August 22, 1848. They had four children: Frederick Dent Grant, Ulysses S. (Buck) Grant, Jr., Ellen (Nellie) Grant, and Jesse Root Grant.

Grant was an uncommonly responsible and devoted father and husband, by some estimates "the most ethical and moral family man and U. S. President that we ever had."Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; refs with no name must have content He was extremely loving and kind towards his wife and children and was always considered a hero in the eyes of his family. Perhaps General Grant was the . The recollection that his wife, children and grandchildren had of him was of the highest caliber.

Grant was an uncommonly devoted parent and expressed his affection for his children in his letters and in his actions. In an era when most fathers physically manhandled their children, he was lenient to a fault. He particularly spoiled his two youngest children, Nellie and Jesse, and they were his special favorites. Horace Porter, one of Grant's staff officers, recalled, "the children often romped with him and he joined in their frolics as if they were all playmates together. The younger ones would hang around his neck while he was writing, make a terrible mess of the papers, and turn everything in his tent into a toy."

The General's wife, Julia, had no illusions about who was the true disciplinarian in the family. She recalled, "The General had no idea of the government of the children. He would have allowed them to do pretty much as they pleased (hunt, fish, swim, etc.) provided it did not interfere with any duty, but his word was law always. Whenever they were inclined to disobey or question my authority, I would ask the General to speak to them. He would, smiling at me, and say to them, 'Come, come Fred, or Nell, you must not quarrel with Mama. She knows what is best for you and you must always obey her.'"

Military career

Mexican War

Grant served in the Mexican-American War (1846–48) under Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, taking part in the battles of Resaca de la Palma, Palo Alto, Monterrey, and Veracruz. He was twice brevetted for bravery: at Molino del Rey and Chapultepec.

Between the Wars

When the Mexican war ended in 1848, Grant remained in the army and was assigned in turn to several different posts. He was sent to Fort Vancouver in the Washington Territory in 1853, where he served as regimental quartermaster of the 4th U.S. Infantry. His wife could not accompany him because his lieutenant's salary did not support a family on the frontier. Also Julia Grant was then eight months pregnant with their second child. The next year, 1854, he was promoted to captain and assigned to command Company F, 4th Infantry, at Fort Humboldt, California. Despite the increase in pay, he still could not afford to bring his family West. He tried some business ventures while in California to supplement his income, but they all failed. He started drinking heavily because of money woes and missing his wife. Because his drinking was having an effect on his military duties, he was given a choice by his superiors: resign his commission or face trial. He resigned on July 31, 1854. Seven years of civilian life followed, during which time he worked first as a farmer, then as a real estate agent in St. Louis, and finally an assistant in the leather shop owned by his father and brother in Galena, Illinois. He went deeply into debt during this time, but remained a devoted father and husband. He once sold his gold pocket watch to get Christmas presents for his family.

Western Theater of the Civil War

Shortly after hostilities broke out on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln put out a call for 75,000 volunteers. When word of his plea reached Galena, Grant made up his mind to get into the war. He helped recruit a company of volunteers, and despite declining the unit's captaincy, he accompanied it to Springfield, Illinois the state capital.

There, Grant met the governor, who offered him a position recruiting volunteers, which Grant accepted. What he really wanted though was a field officer's commission. After numerous failures on his own to attain one, the governor, recognizing that Grant was a West Point graduate, appointed him Colonel of the 21st Illinois Infantry as off June 17, 1861.

With sentiments in Missouri divided, opposing forces began gathering in the state. Shortly after assuming command, Grant's regiment was ordered there, and upon arriving, he concentrated on drilling his men and establishing discipline. Before ever engaging with the enemy, on August 7, he was appointed brigadier general of volunteers. After first serving in a couple of lesser commands, at the end of the month, Grant was assigned command of the critical district of south-east Missouri.

In February 1862, Grant gave the Union cause its first major victory of the war by capturing Forts Henry and Donleson in Tennessee. Grant not only captured the forts' garrisons, but electrified the Northern states with his famous demand at Donelson, "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works."

In early April 1862, he was surprised by Generals Albert Sidney Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard at the Battle of Shiloh. The sheer violence of the Confederate attack sent the Union forces reeling. Grant steadfastly refused to retreat. With grim determination, he stabilized his line. Then, on the second day, with the help of timely reinforcements, Grant counterattacked, turning a serious reverse into a victory.

Despite Shiloh being a Union victory, it came at a high price; it was the bloodiest battle in United States history up until then, with more than 23,000 casualties. Henry W. Halleck, Grant's theater commander, was unhappy by Grant being taken by surprise and by the disorganized nature of the fighting. In response, Halleck took command of the Army in the field himself. Removed from planning strategy, Grant decided to resign. Only by the intervention of his subordinate and good friend, William T. Sherman, did he remain. When Halleck was promoted to general-in-chief of the Union Army, Grant resumed his position as commander of the Army of West Tennessee.

In the campaign to capture the Mississippi River fortress at Vicksburg, Mississippi, Grant spent the winter of 1862–63 conducting a series of operations, attempting to gain access to the city, through the region's bayous. These attempts failed. Grant launched a new plan in the Spring of 1863 and the subsequent operation is considered one of the most masterful in military history.

Grant marched his troops down the west bank of the Mississippi River and crossed the river by using United States Navy ships that had run past the guns at Vicksburg. This resulted in the largest amphibious operation in American military history since the Battle of Vera Cruz in the Mexican American War and would hold that record until the Battle of Normandy in World War II.) There, Grant moved his army inland and, in a daring move defying conventional military principles, cut loose from most of his supply lines[1]. Operating in enemy territory, Grant moved swiftly, never giving the Confederates, under the command of John C. Pemberton, an opportunity to concentrate their forces against him. Grant's army went eastward, captured the city of Jackson, Mississippi, and severed the rail line to Vicksburg.

Knowing that the Confederates could no longer send reinforcements to the Vicksburg garrison, Grant turned west and won at Battle of Champion Hill. The defeated Confederates retreated inside their fortifications at Vicksburg, and Grant promptly surrounded the city. Finding that assaults against the impregnable breastworks were futile, he settled in for a six-week siege which became the Battle of Vicksburg. Cut off and with no possibility of relief, Pemberton surrendered to Grant on July 4, 1863. It was a devastating defeat for the Southern cause, effectively splitting the Confederacy in two, and, in conjunction with the Union victory at Battle of Gettysburg the previous day, is widely considered the turning point of the American Civil War.

In September 1863, the Confederates won the Battle of Chickamauga. Afterwards, the defeated Union forces under William S. Rosecrans retreated to the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee. The victorious Confederate forces, led by Braxton Bragg, followed closely behind. They took up positions on the hillsides, overlooking the city and surrounding the Federals.

On October 17, Grant was placed in overall charge of the besieged forces. He immediately relieved Rosecrans and replaced him with George H. Thomas. Devising a plan known as the "Cracker Line," Grant's chief engineer, William F. "Baldy" Smith, launched the Battle of Wauhatchie (October 28–October 29, 1863) to open the Tennessee River, allowing supplies and reinforcements to flow into Chattanooga, greatly increasing the chances for Grant's forces.

Upon re-provisioning and reinforcing, the morale of Union troops lifted. In late November, 1863 Grant went on the offensive. The Battle of Chattanooga started out with Sherman's failed attack on the Confederate right. Sherman committed tactical errors. He not only attacked the wrong mountain, but committed his troops piecemeal, allowing them to be defeated by a solitary Confederate division. In response, Grant ordered Thomas to launch a demonstration on the center, which could draw defenders away from Sherman. Thomas waited until he was certain that Hooker, with reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac, was engaged on the Confederate left before he launched the Army of the Cumberland at the center of the Confederate line. Despite the delay, Hooker's men broke the Confederate left, while Thomas's division made an unexpected, but spectacular, charge straight up Missionary Ridge and broke the fortified center of the Confederate line. Lt. Arthur MacArthur, father to General Douglas MacArthur, won the Congressional Medal of Honor for taking up and charging forward with his unit's colors. Grant was initially angry at Thomas that his orders for a demonstration were at first delayed and then exceeded, but the assaulting wave sent the Confederates into a head-long retreat, opening the way for the Union to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy.

Grant's willingness to fight and ability to win impressed President Abraham Lincoln, who appointed him lieutenant general—a rank newly authorized by the United States Congress with Grant in mind—on March 2, 1864. On March 12, Grant became general-in-chief of all the armies of the United States.

General-in-chief and strategy for victory

Grant's fighting style was what one fellow general called "that of a bulldog." Although a master of combat by out-maneuvering his opponent (such as at Vicksburg and in the Overland Campaign against Robert E. Lee), Grant was not afraid to order direct assaults or tight sieges against Confederate forces, often when the Confederates were themselves launching offensives against him. Once an offensive or a siege began, Grant refused to stop the attack until the enemy surrendered or was driven from the field. Such tactics often resulted in heavy casualties for Grant's men, but they wore down the Confederate forces proportionately even more and inflicted irreplaceable losses. Grant has been described as a "butcher" for his strategy, particularly in 1864, but he was able to achieve objectives that his predecessor generals had not, even though they suffered similar casualties over time.

In March 1864, Grant put Major General William T. Sherman in immediate command of all forces in the West and moved his headquarters to Virginia where he turned his attention to the long-frustrated Union effort to destroy the army of Lee; his secondary objective was to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, but Grant knew that the latter would happen automatically once the former was accomplished. He devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of the Confederacy from multiple directions: Grant, George G. Meade, and Benjamin Franklin Butler against Lee near Richmond; Franz Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley; Sherman to invade Georgia, defeat Joseph E. Johnston, and capture Atlanta; George Crook and William W. Averell to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; Nathaniel Banks to capture Mobile, Alabama. Grant was the first general to attempt such a coordinated strategy in the war and the first to understand the concepts of total war, in which the destruction of an enemy's economic infrastructure that supplied its armies was as important as tactical victories on the battlefield.

Overland Campaign, Petersburg, and Appomattox

The Overland Campaign was the military thrust needed by the Union to defeat the Confederacy. It pitted Grant against the great commander Robert E. Lee in an epic contest. It began on May 4, 1864, when the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River, marching into an area of scrubby undergrowth and second growth trees known as the Wilderness. It was a terrible place to fight, but Lee sent in his Army of Northern Virginia anyway because he recognized the close confines would prevent Grant from fully exploiting his numerical advantage.

The Battle of the Wilderness was a stubborn, bloody two-day fight. It was an inauspicious start for the Union. Grant was leading a campaign that, in order to win the war, had to destroy the Confederacy's main battle armies. On May 7, with a pause in the fighting, there came one of those rare moments when the course of history fell upon the decision of a single man. Lee backed off, permitting Grant to do what all of his predecessors, as commanders of the Army of the Potomac, had done in this situation, and that was retreat. Grant, ignoring the setback, ordered an advance around Lee's flank to the southeast, lifting the morale of his army.

Siegel's Shenandoah campaign and Butler's James River campaign both failed. Lee was able to reinforce with troops used to defend against these assaults.

The campaign continued, but Lee, anticipating Grant's move, beat him to Spotsylvania, Virginia, where, on May 8, the fighting resumed. The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House lasted 14 days. On May 11, Grant wrote a famous dispatch containing the line "I propose to fight it out along this line if it takes all summer." These words summed up his attitude about the fighting, and the very next day, May 12, he ordered a massive assault that nearly broke Lee's lines.

In spite of mounting Union casualties, the contest's dynamics changed in Grant's favor. Most of Lee's great victories had been won on the offensive, employing surprise movements and fierce assaults. Now, he was forced to continually fight on the defensive. Even after suffering horrific casualties at the Battle of Cold Harbor, Grant kept up the pressure. He stole a march on Lee, slipping his troops across the James River.

Arriving at Petersburg, Virginia, first, Grant should have captured the rail junction city, but he failed because of the overly cautious actions of his subordinate, William F. "Baldy" Smith. Over the next three days, a number of Union assaults were launched, attempting to take the city. But all failed, and finally on June 18, Lee's veterans arrived. Faced with fully manned trenches in his front, Grant was left with no alternative but to settle down to a siege.

Grant approved an innovative plan by Ambrose Burnside's corps to break the stalemate. Before dawn on July 30, they exploded a mine under the Confederate works. But due to last-minute changes in the plan, involving the reluctance of Meade and Grant to allow a division of African-American troops to lead the attack, the ensuing assault was poorly coordinated and lacked vigor. Given an opportunity to regroup, the Confederates took advantage of the situation and counterattacked, winning the Battle of the Crater, and the Federals lost another opportunity to hasten the end of the war.

As the summer drew on and with Grant's and Sherman's armies stalled, respectively in Virginia and Georgia, politics took center stage. There was a presidential election in the fall, and the citizens of the North had difficulty seeing any progress in the war effort. To make matters worse for Abraham Lincoln, Lee detached a small army under the command of Major General Jubal A. Early, hoping it would force Grant to disengage forces to pursue him. Early invaded north through the Shenandoah Valley and reached the outskirts of Washington, D.C.. Although unable to take the city, by simply threatening its inhabitants, Early embarrassed the Administration, making Lincoln's reelection prospects even bleaker.

In early September the efforts of Grant's coordinated strategy finally bore fruit. First, Sherman took Atlanta. Then, Grant dispatched Philip Sheridan to the Shenandoah Valley to deal with Early. It became clear to the people of the North that the war was being won, and Lincoln was reelected by a wide margin. Later in November, Sherman began his March to the Sea. Sheridan and Sherman both followed Grant's strategy of total war by destroying the economic infrastructures of the Valley and a large swath of Georgia and the Carolinas.

At the beginning of April 1865, Grant's relentless pressure finally forced Lee to evacuate Richmond and after a nine-day retreat, Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. There, Grant offered generous terms that did much to ease the tensions between the armies and preserve some semblance of Southern pride, which would be needed to reconcile the warring sides. In his terms of surrender Grant wrote to General Robert E. Lee:

APPOMATTOX COURT-HOUSE, VA.

April 9, 1865

GENERAL: In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th instant, I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate, one copy to be given to an officer to be designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged; and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery, and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officers appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to his home, not to be disturbed by U. S. authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.

U.S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General.

Within a few weeks, the American Civil War was effectively over, although minor actions would continue until Kirby Smith surrendered his forces in the Trans-Mississippi Department on June 2, 1865. The final surrender of Confederate forces happened on June 23 in Indian Territory, when General Stand Watie surrendered his Cherokee troopers to Union Lt. Col. A.C. Matthews. The last Confederate raider, the 'CSS Shenandoah', did not lower its flag until November in Liverpool, England.

Immediately after Lee's surrender, Grant had the sad honor of serving as a pallbearer at the funeral of his greatest champion, Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln had been quoted after the massive losses at Shiloh, "I can't spare this general. He fights." It was a two-sentence description that completely caught the essence of Ulysses S. Grant.

After the war, Congress authorized Grant the newly created rank of General of the Army (the equivalent of a four-star, "full" general rank in the modern Army). He was appointed as such by President Andrew Johnson on July 25, 1866.

Presidency

Grant was the 18th President of the United States and served two terms from March 4, 1869 to March 3, 1877. He was chosen as the Republican presidential candidate at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Illinois on May 20, 1868, with no serious opposition. In the general election that year, he won with a majority of 3,012,833 out of a total of 5,716,082 votes cast or nearly 53 percent of the popular vote.

Grant's presidency was plagued with scandals, such as the Sanborn Incident at the Treasury and problems with U.S. Attorney Cyrus I. Scofield. The most famous scandal was the Whiskey Ring fraud in which more than $3 million in taxes were taken from the federal government. Orville E. Babcock, the private secretary to the President, was indicted as a member of the ring and escaped prison only because of Grant's presidential pardon. After the Whiskey Ring, another federal investigation revealed that Grant's Secretary of War, William W. Belknap, was involved with taking bribes in exchange for the outright sale of Native American trading posts.

Although there is no evidence that Grant himself profited from corruption among his subordinates, he did not take a firm stance against malefactors and failed to react strongly even after their guilt was established. His weakness lay in his selection of subordinates. He alienated party leaders, giving many posts to friends and political contributors, rather than listen to their recommendations. His failure to establish adequate political allies was a large factor behind the scandals getting out of control and becoming newspaper fodder.

Despite all the scandals, Grant's administration presided over significant events in United States history. The most tumultuous was the continuing process of Reconstruction. Grant staunchly favored a limited number of troops stationed in the South. He allowed sufficient numbers to protect rights of southern blacks and suppress the violent tactics of the Ku Klux Klan, but not so many that would harbor resentment in the general population. In 1869 and 1871, Grant signed bills promoting voting rights and prosecuting Klan leaders. The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, establishing voting rights, was ratified during his first term in 1870.

Government affairs

A number of government agencies that remain to the present were instituted during the Grant administration:

- Department of Justice (1870)

- Post Office Department (1872)

- Office of the Solicitor General (1870)

- "Advisory Board on Civil Service" (1871); after it expired in 1873, it became the role model for the Civil Service Commission instituted in 1883 by President Chester A. Arthur, a Grant faithful. Today it is known as the Office of Personnel Management.

- Office of the Surgeon General (1871)

In foreign affairs the greatest achievement of the Grant administration was the Treaty of Washington negotiated by Grant's Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish, in 1871. The treaty was between the United Kingdom and the United States for settling various differences between the two governments, but chiefly those with regard to the Alabama claims. On the domestic side, Grant is remembered for being president when Colorado, the 38th state, was admitted into the Union on August 1, 1876. In November 1876, Grant helped to calm the nation over controversial presidential election dispute between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden. Grant helped quiet the dissent by appointing a federal commission that helped to settle the election in favor of Hayes.

Grant often visited the Willard Hotel, two blocks from the White House to escape the stresses of high office. He referred to the people who approached him in the lobby of the Willard as "those damn lobbyists," possibly giving rise to the modern term lobbyist.

Supreme Court appointments

Grant appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- William Strong – 1870

- Joseph P. Bradley – 1870

- Ward Hunt – 1873

- Morrison Remick Waite (Chief Justice) – 1874

States admitted to the Union

- Colorado – August 1, 1876

Later life

Following his second term, Grant spent two years traveling around the world. He visited Sunderland England, where he opened the country's first free municipal public library. Grant also visited Japan. In the Shibakoen section of Tokyo, a tree Grant planted during his stay grows there still.

In 1879, the Meiji government of Japan announced the annexation of the Ryukyu Islands. China protested, and Grant was invited to arbitrate the matter. He decided that Japan held the stronger claim to the islands and ruled in Japan's favor.

In 1880 Grant contemplated a return to politics and sought the Republican nomination once more. However he failed to gain sufficient support at the Republican party convention that year, which instead went to James Garfield as the nominee.

Grant placed almost all of his financial assets into an investment banking partnership with Ferdinand Ward, during 1881, as suggested by Grant's son Buck (Ulysses, Jr.), who was enjoying great success on Wall Street. Ward was known as the "Young Napoleon of corporate finance." Grant might have taken the use of that appelation more seriously as he had with the other Young Napoleon, George B. McClellan. Failure awaited. In this case, Ward swindled Grant in 1884, bankrupted the company known as Grant and Ward, and fled. And to make matters worse, Ulysses Grant found out at the same time he had developed throat cancer. Grant and his family were left nearly destitute (this was before the era in which retired U.S. Presidents were given pensions).

In one of the most ironic twists in all history, Ward's treachery led directly to a great gift to posterity. Grant's Memoirs are considered a masterpiece, both for their writing style and their historical content, and until Grant bankrupted, he steadfastly refused to write them. Only upon his family's future financial independence becoming in doubt, did he agree to write anything at all.

He first wrote two articles for The Century magazine, which were well received. Afterward, the publishers of The Century made Grant an offer to write his memoirs. It was a standard contract, one which they commonly issued to new writers. Independently from the magazine publishers, the famous author, Mark Twain, approached Grant. Twain, who harbored well-noted suspicions of publishers in general, expressed disdain at the magazine's offer. Twain astutely realized Grant was, at that time, the most significant American alive. He offered Grant a generous contract, including 75 percent of the book's sales as royalties. Grant accepted Twain's offer.

Now terminally ill and in his greatest personal struggle, Grant fought to finish his memoirs. Although wracked with pain and unable to speak at the end, he triumphed, finishing them just a few days before his death. The memoirs succeeded, selling more than 300,000 copies and earning Grant's family more than $450,000 ($9,500,000 in 2005 dollars). Twain heralded the memoirs, terming them "the most remarkable work of its kind since the Commentaries of Julius Caesar." They are widely regarded as among the finest memoirs ever written.

Ulysses S. Grant died at 8:06 a.m. on Thursday July 23, 1885, at Mount McGregor, in Saratoga County, New York. His body lies in New York City, beside that of his wife, in Grant's Tomb, the largest mausoleum in North America.

Legacy

After a listless, mostly unsuccessful series of employments and beset by periods of emotional instability, Ulysses S. Grant emerged from obscurity to play a central role in history for which he was uniquely suited. As a Civil War general, Grant possessed the rare combination of dogged will, strategic vision, humility, and empathetic leadership to command the Union armies in an exhausting campaign against fellow Americans.

Grant shared the military objectives of the commander in chief, President Abraham Lincoln, but more importantly, shared Lincoln's moral vision of a nation freed from the stain of slavery and united as one people based on the nation's founding ideals. The relationship of trust and respect between Lincoln and Grant enabled the war to be prosecuted relentlessly, yet ever with the objective of a people reconciled and at peace. Grant's generous peace terms at Appomattox and Lincoln's eloquent reminders of the "mystic chords of memory" that bound all American together, that northerners and southerners were "not enemies, but friends," were the foundation of the period of southern Reconstruction.

A grateful nation twice elected Grant to the presidency, but his military skills were poorly suited to civilian leadership. Grant's reputation suffered as a result of scandals in his administration. although he was not personally implicated.

In World War II, the British Army produced an armored vehicle known as the Grant tank (a version of the American M3 model, which was ironically nicknamed "Lee").

Grant's portrait appears on the U.S. fifty-dollar bill.

The Ulysses S. Grant Memorial, located on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., honors Grant.

There is a U.S. Grant Bridge over the Ohio River at Portsmouth, Ohio.

Counties in ten U.S. states are named after Grant: Arkansas, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

| Preceded by: (none) |

Commander of the Army of the Tennessee 1862-1863 |

Succeeded by: William T. Sherman |

| Preceded by: (none) |

Commander of Union Armies in the West 1863-1864 |

Succeeded by: William T. Sherman |

| Preceded by: Henry W. Halleck |

Commanding General of the United States Army 1864-1869 |

Succeeded by: William T. Sherman |

| Preceded by: Abraham Lincoln |

Republican Party presidential candidate 1868 (won), 1872 (won) |

Succeeded by: Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Preceded by: Andrew Johnson |

President of the United States March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1877 |

Succeeded by: Rutherford B. Hayes |

| |||||||

| |||||

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. 2001. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780804736411.

- Fuller, J.F.C. 1957. Grant and Lee, A Study in Personality and Generalship. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253134005.

- Smith, Jean Edward. 2001. Grant. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684849263.

- Catton, Bruce. 1990. Grant Takes Command. Boston, MA: Little, Brown. ISBN 9780316132404.

External links

- First Inaugural Address. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- Second Inaugural Address. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- White House Biography. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- Works by Ulysses S. Grant. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.