Reconstruction

Reconstruction is the name of the historical period following the American Civil War during which the U.S. government attempted to resolve the divisions of the war, rebuild the southern economy, and integrate former slaves into the political and social life of the country. With the end of the war and the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865, Southern states which had borne the brunt of the war were in ruins. Slavery was abolished first among states in rebellion by the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and later by the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865. Reconstruction addressed the return of the Southern states that had seceded, the status of ex-Confederate leaders, and the Constitutional and legal status of the African-American Freedmen.

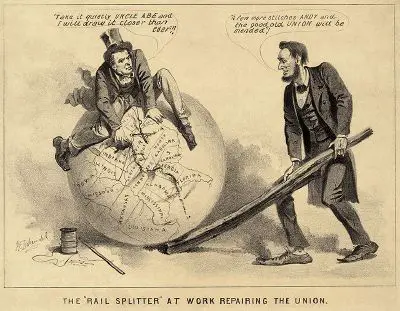

Reconstruction is generally dated from 1865 to 1877, but some historians include a phase of Presidential Reconstruction from 1863 to 1866 during which Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson advanced policies designed to restore U.S. sovereignty over rebellious states. Their moderate programs were opposed by the Radical Republicans, a political faction that gained power after the 1866 elections and began Radical Reconstruction, from 1866-1873, emphasizing civil rights and voting rights for the Freedmen. Violent controversy arose when a Republican coalition of freedmen, northern reformers, and white southern supporters of Reconstruction assumed control of most of the southern states. In the so-called Redemption, 1873-1877, white supremacist Southerners defeated the Republicans and took control of each southern state, marking the end of Reconstruction and the federal attempt to integrate freedmen into the political, economic, and social system of the American South.

President Lincoln's objectives in war, first to preserve the Union and later to eradicate slavery, which he saw as a stain on the nation's ideals, were also the guiding principles of Lincoln's Reconstruction policies. Reconstruction following Lincoln's assassination followed a more radical path. The goal of integrating former slaves into the mainstream of southern life, while well-intentioned, foundered because of coercive military means, pervasive racial prejudices, and political corruption. The faith-driven abolitionist movement also abandoned the cause of social justice for freed slaves, engendering a harsh racial caste system in the American South that would endure until the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Policy issues

Following the surrender of Confederate forces at Appomattox, Virginia, in April 1865, Republican leaders agreed that slavery and the slave power had to be permanently destroyed, and that all forms of Confederate nationalism had to be suppressed. Moderates sought to accomplish this through gradualist approaches, including the partial enfranchisement of freedmen and lenient reinstatement of citizenship rights of former Confederates.

Radicals said that the ex-Confederates could not be trusted. Conservatives (including most white Southerners, Northern Democrats, and some Northern Republicans) opposed black voting. Lincoln took a middle position that would allow some black men to vote, especially army veterans. Lincoln proposed giving the vote to "the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks."[1]

The assassination of President Lincoln, the leader of the moderate Republicans, and the election of 1866 decisively changed the balance of power, giving the Radicals control of Congress and enough votes to overcome the vetoes of President Andrew Johnson, who had assumed office. Johnson was a Tennessee senator who opposed secession yet was a defender of slavery and thus played an anomalous role during Reconstruction. In 1864, while military governor of Tennessee, Johnson supported black enfranchisement, saying, "The better class of [freedmen] will go to work and sustain themselves, and that class ought to be allowed to vote, on the ground that a loyal negro is more worthy than a disloyal white man." As President in 1865, Johnson wrote to the governor of Mississippi, recommending, "If you could extend the elective franchise to all persons of color who can read the Constitution in English and write their names, and to all persons of color who own real estate valued at not less than two hundred and fifty dollars, and pay taxes thereon, you would completely disarm the adversary [Radicals in Congress], and set an example the other states will follow."[2]

Congress impeached Johnson over his dismissal of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. He was acquitted in the Senate by one vote, but he remained almost powerless regarding Reconstruction policy. Radicals used the Army to take over the South and give the vote to black men, and they took the vote away from an estimated 10,000 or 15,000 white men who had been Confederate officials or senior officers. Thaddeus Stevens proposed, unsuccessfully, that all ex-Confederates lose the vote for five years. The compromise that was reached disenfranchised many ex-Confederate civil and military leaders; no one knew how many temporarily lost the vote, but one estimate was 10,000 to 15,000.[3]

Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, leaders of the Radical Republicans, were initially hesitant to enfranchise the largely illiterate ex-slave population. However, Sumner and Stevens finally decided it was necessary for blacks to vote for their own protection; for the protection of white Unionists (scalawags); and for the peace of the country.[4]

The Radicals passed laws allowing all male freedmen to vote, and in 1867, black men voted for the first time. Over the course of Reconstruction, more than 1,500 African Americans held public office in the South. The question of women's suffrage was also debated but was rejected.

The South's postwar white leaders renounced secession and slavery, but they were angered in 1867, when their state governments were ousted by federal military forces and replaced by Republican lawmakers elected by blacks, southern supporters of Reconstruction (Scalawags), and northern Republican Carpetbaggers.

Presidential Reconstruction, 1863-1866

Lincoln's plan

Planning for Reconstruction began as early as 1861, at the onset of secession, with little premonition in the administration of what would prove to be the extent or duration of the Civil War. By 1863, the Union had won some strategic victories, notably by retaking the Mississippi and occupying territories in the Deep South, and Lincoln proposed certain tactical steps of restoration. Motivated by a desire to build a strong Republican Party in the South, by signs of southern disaffection with the war, and by eagerness to end the bitterness engendered by war, on December 8, 1863, he issued a proclamation of amnesty and reconstruction for those areas of the Confederacy occupied by Union armies. The so-called Ten Percent Plan offered pardon, with certain exceptions, to any Confederate who would swear to support the Constitution and the Union. Once a group in any state equal in number to one tenth of that state's total vote in the presidential election of 1860 took the prescribed oath and organized a government that abolished slavery, he would grant that government executive recognition.

Lincoln's 1863 plan aroused the sharp opposition of the radicals in Congress, who believed it would simply restore to power the old planter aristocracy. In July 1864, radical Republicans passed the Wade-Davis Bill, which required 50 percent of a state's male voters to take an "Ironclad Oath" that they had never voluntarily supported the Confederacy. Lincoln's veto kept the Wade-Davis Bill from becoming law, the Radicals lost momentum, and he implemented his own plan. By the end of the war it had been adopted in Union-controlled territory in Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Virginia. Congress, however, refused to seat the senators and representatives elected from those states, and by the time of Lincoln's assassination the President and Congress were at a stalemate.[5]

Observers at the time of the Wade-Davis bill—and historians since—agree that probably no state would have qualified, leaving them under military control indefinitely. By vetoing the bill, Lincoln blocked the Radicals from a dominant role in government, though they rose to power again in 1866. Historian William Gienapp explains Lincoln's veto:

Lincoln, in contrast, shrank from inaugurating a fundamental upheaval in southern society and mores, and by stressing future over past loyalty, he was willing to allow recanting Rebels to dominate the new southern governments. Moreover, Lincoln believed that the best strategy was to introduce black suffrage in the South by degrees in order to accustom southern whites to blacks voting. How far he was willing to go in extending rights to former slaves remained unclear, but his gradualist approach to social change remained intact, just as when he had tried to get the border states in 1862 to adopt gradual emancipation. Finally, the radicals and Lincoln held quite different views of the relationship of Reconstruction to the war effort. By erecting impossibly high standards that no Southern state could meet, the Wade–Davis bill sought to postpone Reconstruction until the war was over. For Lincoln, in contrast, a lenient program of Reconstruction would encourage Southern whites to abandon the Confederacy and thus was integral to his strategy for winning the war.[6]

On March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered his Second Inaugural Address, reaffirming his generous stance toward the reunification of Confederate states: "With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations."

On April 11, 1865, Lincoln delivered his last public address, in which he continued to uphold a lenient reconstruction policy. Insisting as well that there be new rights for the Freedmen, he created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in January 1865, known as the Freedmen's Bureau. In one experiment in the Sea Islands of South Carolina, Freedmen were allowed to farm plantations seized by the Army, although they never received ownership.

Johnson's presidential reconstruction: 1865–1866

Northern anger over the assassination of Lincoln and the immense human cost of the war led to demands for harsh, punitive policies toward the defeated South. Vice President Andrew Johnson had taken a hard line and spoken of hanging rebel Confederates, but when he succeeded Lincoln as President he took a much softer approach, pardoning many Confederate leaders and allowing ex-Confederates to maintain their control of Southern state governments, Southern lands, and, informally, even many former slaves.[7] Confederate President Jefferson Davis was held in prison for two years, but not the other Confederate leaders were imprisoned and there were no treason trials. Only one person—Captain Henry Wirz, the commandant of the infamous prison camp in Andersonville, Georgia—was executed for war crimes.

Black codes

The Johnson government quickly enacted "black codes," giving freedmen more rights than free blacks had before the war, but still limited, second-class civil rights, and no voting rights. Southern plantation owners feared extensive black vagrancy would mean loss of the essential labor force, and many Southern whites rejected the notion of equality with Southern blacks. Two states had full fledged Black Codes—Mississippi and South Carolina. Among other provisions, they stringently limited blacks' ability to control their own employment.[8]

In response to the Black codes, which outraged northern opinion, and worrisome signs of Southern recalcitrance, Radical Republicans blocked the readmission of former Confederate states to the Congress in fall 1865. Congress also renewed the Freedman's Bureau, but Johnson vetoed the Freedmen's Bureau Bill in February 1866. Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, leader of the moderate Republicans, then proposed the first Civil Rights Law. The abolition of slavery was empty, he said, if "laws are to be enacted and enforced depriving persons of African descent of privileges which are essential to freemen…. A law that does not allow a colored person to go from one county to another, and one that does not allow him to hold property, to teach, to preach, are certainly laws in violation of the rights of a freeman…. The purpose of this bill is to destroy all these discriminations."[9]

According to the bill:

All persons born in the United States … are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens of every race and color, without regard to any previous condition of slavery … shall have the same right in every State … to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties and to none other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom to the Contrary notwithstanding.

Congress quickly passed the Civil Rights bill; the Senate on February 2, voted 33–12; the House on March 13, voted 111–38.

Johnson breaks with Radical Republicans

Although strongly urged by moderates in Congress to sign the Civil Rights bill, Johnson broke decisively with them by vetoing it on March 27. His veto message objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the Freedmen at a time when eleven out of thirty-six states were unrepresented and attempted to establish by Federal law "a perfect equality of the white and black races in every State of the Union." Johnson said it was an invasion by Federal authority of the rights of the States, had no warrant in the Constitution, was contrary to all precedents, and was a "stride toward centralization and the concentration of all legislative power in the national government."[10]

The Democratic Party, proclaiming itself the party of white men, north and south, supported Johnson.[7] However, the Republicans in Congress overrode his veto (the Senate by the close vote of 33:15, the House by 122:41) and the Civil Rights bill became law. Congress also passed the Freedmen's Bureau Bill over Johnson's veto.

Constitutional amendments and black officeholders

Three new Constitutional amendments were adopted in succession following the conclusion of the Civil War. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery and was ratified in 1865. The Fourteenth Amendment was designed to put the key provisions of the Civil Rights Act into the Constitution, but it went much further. It extended citizenship to everyone born in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction (excepting visitors and Native Americans on reservations), penalized states that did not give the vote to Freedmen, and most importantly, created new federal civil rights that could be protected by federal courts. It also guaranteed the Federal war debt (and promised the Confederate debt would never be paid by the federal treasury). Johnson used his influence to block the amendment in the states, since three-fourths of the states were required for ratification, although the amendment was soon ratified.

The Fifteenth Amendment passed in 1870, decreeing that the right to vote could not be denied because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The amendment did not declare suffrage an unconditional right and only prohibited specific types of discrimination, while specific electoral policies were determined within each state. Notably, the Fifteenth Amendment did not enfranchise women.

Radical reconstruction: 1866–1873

The moderate effort to compromise with Johnson had failed, and a political fight broke out between the Republicans (both Radical and moderate) on one side, and Johnson and his allies in the Democratic party in the North, and the conservatives (who used different names) in each southern state on the other side.

Following the election of 1866, Republicans took control of all Southern state governorships and state legislatures, leading to the election of numerous African-Americans to state and national offices, as well as to the installation of African-Americans into other positions of power.

Military reconstruction

The South remained defiant in adapting to social changes, and a pervasive insurgency emerged in many regions against free blacks and Union supporters (and in a few cases, Union veterans). As retribution against the violence, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act.

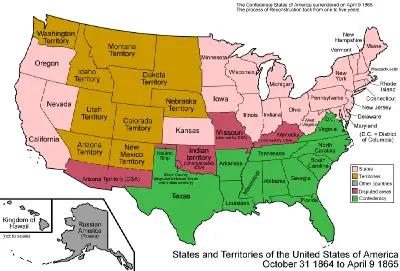

The first Reconstruction Act placed ten former Confederate states under military control, grouping them into five military districts:[11]

- First Military District: Virginia, under General John Schofield

- Second Military District: The Carolinas, under General Daniel Sickles

- Third Military District: Georgia, Alabama, and Florida, under General John Pope

- Fourth Military District: Arkansas and Mississippi, under General Edward Ord

- Fifth Military District: Texas and Louisiana, under Generals Philip Sheridan and Winfield Scott Hancock

Tennessee was not made part of a military district, and therefore federal controls did not apply.

The ten Southern state governments were re-constituted under the direct control of the United States Army. There was little or no fighting, but rather a state of martial law in which the military closely supervised local government and elections, and protected office holders from violence.[12] Blacks were enrolled as voters, while former Confederate leaders were excluded. In some cases whites were rejected or refused to register while blacks were significantly overrepresented as a percent of all voters.

All Southern states were readmitted to the Union by the end of 1870, the last being Georgia. All but 500 top Confederate leaders were pardoned when President Grant signed the Amnesty Act of 1872.

Public schools

As modernizers, the Republicans believed that education was a long-term solution to the poverty and the social disorder of the South. They accordingly created a system of public schools, which were segregated by race everywhere except New Orleans. Most blacks approved the segregated schools because they provided jobs for black teachers and kept their children in a safer learning environment. Teachers were poorly paid, and their pay was often in arrears.[13] Conservatives contended the rural schools were too expensive and unnecessary for a region where the vast majority of people were cotton or tobacco farmers. One historian found that the schools were not very effective because of "poverty, the inability of the states to collect taxes, and inefficiency and corruption in many places prevented successful operation of the schools."[14]

Numerous private academies and colleges for Freedmen were also established by northern missionaries. Every state created state colleges for Freedmen, and in 1890, after Reconstruction ended, black state colleges started receiving federal funds as land grant schools because many fair-minded Democrats supported the liberal education of both races.[15]

Railroad subsidies and payoffs

Every Southern state subsidized railroads, which modernizers felt could haul the region out of isolation and poverty. Despite corruption, in which millions of dollars in bonds and subsidies were fraudulently pocketed, and higher taxes across the South to pay off the railroad bonds and the school costs,[16] thousands of miles of lines were built as the Southern system expanded from 11,000 miles (17,700 km) in 1870 to 29,000 miles (46,700 km) in 1890. Although the lines were owned and directed overwhelmingly by Northerners, railroads helped create a mechanically skilled group of craftsmen and indeed broke the isolation of much of the region. Passengers were few, however, and apart from hauling the cotton crop when it was harvested, the effects of corruption, according to one businessman, "was to drive capital from the State, paralyze industry, and demoralize labor."[17]

The new spending on schools and especially on railroad subsidies, combined with fraudulent spending and collapsing state credit caused by huge deficits, forced the states to dramatically increase tax rates—up to ten times higher—despite the poverty of the region. Angry taxpayers revolted, and the conservatives shifted their focus away from race to taxes.[18]

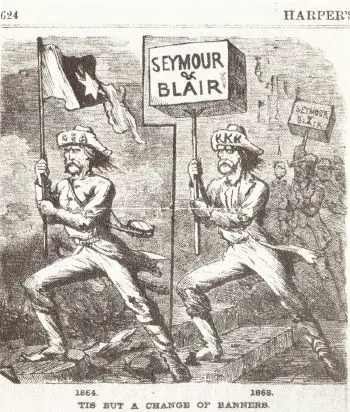

Conservative reaction and creation of the Ku Klux Klan

The white Southerners who lost power reformed themselves into "Conservative" parties that battled the Republicans. The party names varied, but by the late 1870s, they effectively joined the Democrats. Writing in 1907, historian Walter Lynwood Fleming describes mounting anger of Southern whites, noting that "the Negro troops, even at their best, were everywhere considered offensive by the native whites…. The Negro soldier, impudent by reason of his new freedom, his new uniform, and his new gun, was more than Southern temper could tranquilly bear, and race conflicts were frequent."

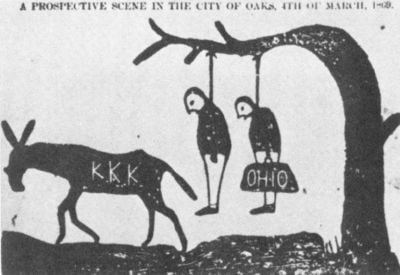

Reaction by conservatives included the formation of violent secret societies, especially the Ku Klux Klan. Founded by six educated, middle-class Confederate veterans at the end of the American Civil War on December 24, 1865, the original Ku Klux Klan sought to limit the political and social advancement of the freed slaves, specifically to curb black education, economic advancement, voting rights, and the right to bear arms. However, although the Klan's focus was mainly African Americans, Southern Republicans also became the target of vicious intimidation tactics.

The Klan soon spread into nearly every southern state, launching a reign of terror against Republican leaders, both black and white. The Klan soon began breaking up black prayer meetings and invading black homes at night to steal firearms. Violence occurred in cities and in the countryside between white former Confederates, Republicans, African-Americans, representatives of the federal government, and Republican-organized and armed Loyal Leagues.

Klan intimidation was often targeted at schoolteachers and operatives of the federal Freedmen's Bureau, many of whom had before the war been abolitionists or active in the underground railroad. Many white southerners believed that blacks were voting for the Republican Party only because they had been hoodwinked by the Loyal Leagues. Black members of the Loyal Leagues were also the frequent targets of Klan raids.

Klansmen killed more than 150 African Americans in a single county in Florida, and hundreds more in other counties.[19]

Although Klan public statements affirmed that the Klan was a peaceful organization, a federal grand jury in 1869 determined that the Klan was a "terrorist organization," and hundreds of indictments for crimes of violence and terrorism were issued. Klan members were prosecuted, and many fled jurisdiction, particularly in South Carolina.[20]

Many non-Klan members found the Klan's uniform to be a convenient way to hide their identities when carrying out acts of violence. However, it was also convenient for the higher levels of the organization to disclaim responsibility for such acts, and the secretive, decentralized nature of the Klan made membership difficult to prove. According to historian Eric Foner, in many ways the Klan was a military force serving the interests of the Democratic Party, the planter class, and those who desired the restoration of white supremacy.[21]

By 1868, only two years after the Klan's creation, its activity was already beginning to decrease and many influential southern Democrats were beginning to see it as a liability, an excuse for the federal government to retain its power over the South. It was effectively dismantled by President Grant's passage and enforcement of the Force Acts of 1870 and 1871, only to be reestablished in 1915.

Redemption 1873-1877

Republicans split nationally: Election of 1872

As early as 1868, Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, a leading Radical during the war, concluded:

Congress was right in not limiting, by its reconstruction acts, the right of suffrage to whites; but wrong in the exclusion from suffrage of certain classes of citizens and all unable to take its prescribed retrospective oath, and wrong also in the establishment of despotic military governments for the States and in authorizing military commissions for the trial of civilians in time of peace. There should have been as little military government as possible; no military commissions; no classes excluded from suffrage; and no oath except one of faithful obedience and support to the Constitution and laws, and of sincere attachment to the constitutional Government of the United States.[22]

In the South, political–racial tensions built up inside the Republican party. In 1868, Georgia Democrats, with support from some Republicans, expelled all 28 black Republican members (arguing blacks were eligible to vote but not to hold office). In several states the more conservative southern white supporters of Reconstruction, knows as scalawags, fought for control with the more radical northern white carpetbaggers and usually lost. Thus, in Mississippi, the conservative faction led by scalawag James Lusk Alcorn was decisively defeated by the radical faction led by carpetbagger Adelbert Ames. The party lost support steadily as many scalawags left it; few new recruits were acquired. Meanwhile, the Freedmen were demanding a much bigger share of the offices and patronage, thus squeezing out their carpetbagger allies.[23] Finally some of the more prosperous Freedmen were joining the Democrats, angered at the failure of the Republicans to help them acquire land.[24] Although some Marxist historians, especially W.E.B. Du Bois, looked for and celebrated a cross-racial coalition of poor whites and poor blacks, such coalition rarely formed. Congressman Lynch explains that,

While the colored men did not look with favor upon a political alliance with the poor whites, it must be admitted that, with very few exceptions, that class of whites did not seek, and did not seem to desire such an alliance.

Lynch explains that poor whites resented the job competition from Freedmen. Furthermore, the poor whites

…with a few exceptions, were less efficient, less capable, and knew less about matters of state and governmental administration than many of the ex-slaves. …As a rule, therefore, the whites that came into the leadership of the Republican party between 1872 and 1875 were representatives of the most substantial families of the land.[15]

Thus, the poor whites became Democrats and bitterly opposed the black Republicans.

Democrats try a "New Departure"

By 1870, the Democratic–Conservative leadership across the South decided it had to end its opposition to Reconstruction as well as to black suffrage in order to survive and move on to new issues. The Grant administration had proven by its crackdown on the Ku Klux Klan that it would use as much federal power as necessary to suppress open anti-black violence. The Democrats in the North concurred. They wanted to fight the GOP on economic grounds rather than race. The New Departure offered the chance for a clean slate without having to refight the Civil War every election. Furthermore, many wealthy landowners thought they could control part of the newly enfranchised black electorate to their own advantage.

Not all Democrats agreed; a hard core element wanted to resist Reconstruction at all costs. Eventually, a group called "Redeemers" took control of the party in the states.[25] They formed coalitions with conservative Republicans, including scalawags and carpetbaggers, emphasizing the need for economic modernization. Railroad building was seen as a panacea since northern capital was needed. The new tactics were a success in Virginia, where William Mahone built a winning coalition. In Tennessee, the Redeemers formed a coalition with Republican governor DeWitt Senter. Across the South, Democrats switched from the race issue to taxes and corruption, charging that Republican governments were corrupt and inefficient, as taxes began squeezing cash-poor farmers who rarely saw $20 in currency a year but had to pay taxes in currency or lose their farm.

By 1872, President Grant had also alienated large numbers of leading Republicans, including many Radicals by the wanton corruption of his administration and his use of federal soldiers to prop up Radical state regimes in the South. The opponents, called "Liberal Republicans," included Republican founders who expressed dismay that the party had succumbed to corruption. Leaders of the new party included editors of some of the nation's most powerful newspapers. Charles Sumner, embittered by the corruption of the Grant administration, joined the new party, which nominated editor Horace Greeley. The badly disorganized Democratic party also supported Greeley.

Grant made up for the defections by new gains among Union veterans, as well as strong support from the "Stalwart" faction of his party (which depended on his patronage), and the Southern Republican parties. Grant won a smashing landslide, as the Liberal Republican party vanished and many former supporters—even ex-abolitionists—abandoned the cause of Reconstruction.[26]

In North Carolina, Republican Governor William Woods Holden used state troops against the Klan, but the prisoners were released by federal judges. Holden became the first governor in American history to be impeached and removed from office. Republican political disputes in Georgia split the party and enabled the Redeemers to take over.[27] Violence was a factor in neutralizing Republican leaders in the Deep South, with its larger black Republican population. In the North, a live-and-let-live attitude made elections more like a sporting contest. But in the Deep South, it affected the lives of the citizens. As an Alabama scalawag explained, "Our contest here is for life, for the right to earn our bread … for a decent and respectful consideration as human beings and members of society."[28]

Panic of 1873 weakens GOP

The Panic of 1873 hit the Southern economy hard and disillusioned many Republicans who had gambled that railroads would pull the South out of its poverty. The price of cotton fell by half; many small landowners, local merchants and cotton factors (wholesalers) went bankrupt. Sharecropping, for both black and white farmers, became more common as a way to spread the risk of owning land. The old abolitionist element in the North was aging away, or had lost interest, and was not replenished. Many carpetbaggers returned to the North or joined the Redeemers. Blacks had an increased voice in the Republican Party, but across the South it was divided by internal bickering and was rapidly losing its cohesion. Many local black leaders started emphasizing individual economic progress in cooperation with white elites, rather than racial political progress in opposition to them, a conservative attitude that foreshadowed Booker T. Washington.[29]

Nationally, President Grant took the blame for the depression; the Republican Party lost 96 seats in all parts of the country in the 1874 elections. The Bourbon Democrats took control of the House and were confident of electing Samuel J. Tilden president in 1876. President Grant was not running for re-election and across the South states fell to the Redeemers, with only four in Republican hands in 1873, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina; Arkansas then fell in 1874. Political violence was endemic in Louisiana, but efforts to seize the state government were repulsed by federal troops who entered the state legislature and hauled away several Democratic legislators.

The violation of tradition embarrassed Grant, and some of his cabinet recommended against further intervention.[30] By now, all Democrats and most northern Republicans agreed that Confederate nationalism and slavery were dead—the war goals were achieved—and further federal military interference was an undemocratic violation of historic Republican values. The victory of Rutherford Hayes in the hotly contested Ohio gubernatorial election of 1875 indicated his "let alone" policy toward the South would become Republican policy, as indeed happened when he won the 1876 GOP nomination for president. The last explosion of violence came in Mississippi's 1875 election, in which Democratic rifle clubs, operating in the open and without disguise, threatened or shot enough Republicans to decide the election for the Redeemers. Republican Governor Adelbert Ames asked Grant for federal troops to fight back; Grant refused, saying public opinion was "tired out" of the perpetual troubles in the South. Ames fled the state as the Democrats took over Mississippi.[31]

1876 election and era of segregation

Reconstruction continued in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida until 1877. After Hayes won the disputed election of 1876, the Compromise of 1877 was reached whereby the white South agreed to accept Hayes's victory if he withdrew the last Federal troops.

The end of Reconstruction marked the beginning of a period, 1877–1900, that saw the steady reduction of many civil and political rights for African-Americans, and ushered in the nadir of American race relations. The process varied by states and towns. In Virginia, the Redeemers gerrymandered cities to minimize Republican seats; reduced the number of polling places in black precincts; made local officials appointees of the state legislature; and did not allow the vote to felons or to people who failed to pay their annual poll tax.

Much of the Reconstruction civil rights legislation was overturned by the United States Supreme Court. Most notably, the court held in the Civil Rights Cases (1883), that the 14th amendment only gave Congress the power to outlaw public, rather than private, discrimination. In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) the court went even further, announcing that state-mandated segregation was legal as long as the law provided for "separate but equal" facilities.

In the decades that followed, blacks suffered increasing hardships as legal protections eroded and racist Jim Crow laws and institutions marginalized blacks.

Legacy and historiography

Interpretations of Reconstruction have varied widely, yet nearly all historians have concluded that the federal effort to resolve the divisions of war and the social integration of freedmen was a failure. In the 1865-1975 period, many saw ex-Confederates as traitors and Johnson their ally, who threatened to undo the Union's Constitutional achievements. In the 1870s and 1880s it was widely argued that Johnson and his allies were not traitors, but rather blundered badly in rejecting the 14th Amendment and setting the stage for Radical Reconstruction.[32]

Among black scholars, Booker T. Washington, who grew up in West Virginia during Reconstruction, concluded that, "the Reconstruction experiment in racial democracy failed because it began at the wrong end, emphasizing political means and civil rights acts rather than economic means and self-determination."[33] His solution was to concentrate on building the economic infrastructure of the black community.

In the 1930s, revisionist disciples of historian Charles A. Beard focused on economics, downplaying politics and constitutional issues. They argued that the Radical rhetoric of equal rights was mostly a smokescreen hiding the true motivation of Reconstruction's real backers. While conceding that a few men like Stevens and Sumner were thoroughly idealistic, Howard Beale argued Reconstruction was primarily a successful attempt by financiers, railroad builders, and industrialists in the Northeast, using the Republican Party, to control the national government for its own selfish economic ends. Those ends were to continue the wartime high protective tariff and the new network of national banks, and to guarantee a "sound" currency. To succeed, the business class had to remove the old ruling agrarian class of Southern planters and Midwestern farmers. This it did through Reconstruction, which made the South Republican. However, historians in the 1950s and 1960s refuted Beale's economic causation by demonstrating that Northern businessmen were widely divergent on monetary or tariff policy, and seldom paid attention to Reconstruction issues.[34]

In the 1960s, neoabolitionist historians emerged, led by John Hope Franklin, Kenneth Stampp, and Eric Foner. Strongly aligned with the Civil Rights Movement, they found a great deal to praise in Radical Reconstruction. Foner, the primary advocate of this view, argued that it was never truly completed, and that a Second Reconstruction was needed in the late twentieth century to complete the goal of full equality for African-Americans. The neoabolitionists followed the revisionists in minimizing the corruption and waste created by Republican state governments, instead emphasizing that poor treatment of Freedmen was a worse scandal and a grave corruption of America's republican ideals. They argued that the real tragedy of Reconstruction was not that it failed because blacks were incapable of governing, but that it failed because the civil rights and equalities granted during this period were but a passing, temporary development. These rights were suspended in the South from the 1880s through 1964, but were restored by the Civil Rights Movement that is sometimes referred to as the "Second Reconstruction."

More recent scholarship has encouraged greater attention to race, religion, and issues of gender while at the same time pushing the "end" of Reconstruction to the end of the nineteenth century, while monographs by other historians have offered new views of the southern "Lost Cause."

Notes

- ↑ William Gienapp, Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America (Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0195151008).

- ↑ John Hope Franklin, Reconstruction after the Civil War (University of Chicago Press, 1961, ISBN 0226260798), 42.

- ↑ Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper & Row 1988, ISBN 9780060158514), 273-276.

- ↑ William E. Gienapp, (ed.), The Civil War and Reconstruction: A Documentary Collection (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, ISBN 978-0393975550).

- ↑ William Harris, The Day of the Carpetbagger: Republican Reconstruction in Mississippi (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979, ISBN 9780807103661).

- ↑ Gienapp 2002, 167.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1989, ISBN 978-0393026733).

- ↑ Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, A History of the United States Since the Civil War: 1865-68. Vol. 1 (Palala Press, 2015 (original 1917), ISBN 1340586940), 128–129.

- ↑ James F. Rhodes, History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley–Bryan Campaign of 1896 Vol 6 (Wentworth Press, 2016 (original 1920), ISBN 978-1363176304), 65-66.

- ↑ Rhodes, 68.

- ↑ Foner, 6.

- ↑ Foner.

- ↑ Foner, 365–368.

- ↑ Franklin, 139.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 John R. Lynch, The Facts of Reconstruction The Neale Publishing Company, 1913. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ↑ Franklin, 141-148.

- ↑ Franklin, 147–148.

- ↑ Foner, 415–416.

- ↑ Michael Newton, The Invisible Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Florida (University Press of Florida, 2001, ISBN 0813021200).

- ↑ Allen W. Trelease, White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction (Praeger, 1979, ISBN 978-0313211683).

- ↑ Foner, 426.

- ↑ J. W. Schuckers, The Life and Public Services of Salmon Portland Chase (Literary Licensing, LLC, 2014 (original 1874), ISBN 978-1497814059).

- ↑ Foner, 537-541.

- ↑ Foner, 374-375.

- ↑ Michael Perman, The Road to Redemption: Southern Politics, 1869–1879 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0807841419).

- ↑ James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (Oxford University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0195055429).

- ↑ Foner.

- ↑ Foner, 443.

- ↑ Foner, 545–547.

- ↑ Foner, 555–556.

- ↑ Foner.

- ↑ Fletcher M. Green, Walter Lynwood Fleming: Historian of Reconstruction The Journal of Southern History 2(4) (Nov, 1936): 497-521.

- ↑ Louis R. Harlan, Booker T. Washington in Perspective (University Press of Mississippi, 2006, ISBN 978-1578069286).

- ↑ Foner.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berlin, Ira, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland (eds.). Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War. New York: The New Press, 1992. ISBN 9781565840157

- Blaine, James Gillespie. Twenty Years of Congress, from Lincoln to Garfield: With a review of the events which led to the political revolution of 1860. Gale, 2010 (original 1884). ISBN 978-1240106127

- Fleming, Walter L. Documentary History of Reconstruction, Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational & Industrial, 1865 to the Present Time. HardPress Publishing, 2013 (original 1906). ISBN 978-1314628685

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: Harper & Row 1988. ISBN 9780060158514

- Franklin, John Hope. Reconstruction after the Civil War. University of Chicago Press, 1961. ISBN 0226260798

- Gienapp, William E. (ed.). The Civil War and Reconstruction: A Documentary Collection. W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 978-0393975550

- Gienapp, William E. Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0195151008

- Harlan, Louis R. Booker T. Washington in Perspective. University Press of Mississippi, 2006. ISBN 978-1578069286

- Harris, William. The Day of the Carpetbagger: Republican Reconstruction in Mississippi. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979. ISBN 9780807103661

- Hyman, Harold Melvin (ed.). The Radical Republicans and Reconstruction, 1861-1870. Bobbs-Merrill, 1969. ISBN 978-0672600708

- Lynch, John R. The Facts of Reconstruction The Neale Publishing Company, 1913. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- McPherson, James M. Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0195055429

- Newton, Michael. The Invisible Empire: The Ku Klux Klan in Florida. University Press of Florida, 2001. ISBN 0813021200

- Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. A History of the United States Since the Civil War: 1865-68. Vol. 1. Palala Press, 2015 (original 1917). ISBN 1340586940

- Perman, Michael. The Road to Redemption: Southern Politics, 1869–1879. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0807841419

- Rhodes, James F. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley–Bryan Campaign of 1896 Vol 6. Wentworth Press, 2016 (original 1920). ISBN 978-1363176304

- Schuckers, J. W. The Life and Public Services of Salmon Portland Chase. Literary Licensing, LLC, 2014 (original 1874). ISBN 978-1497814059

- Sumner, Charles, and Beverly Wilson Palmer. The Selected Letters of Charles Sumner. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1990. ISBN 9781555530785

- Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1989. ISBN 978-0393026733

- Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. Praeger, 1979. ISBN 978-0313211683

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

- Reconstruction Historiography: A Source of Teaching Ideas by Robert P. Green, Jr. (1991)

- After the war: a southern tour, May 1, 1865 to May 1, 1866. (1866) by Whitelaw Reid

- History of the Thirty-ninth Congress of the United States. (1868) by William Horatio Barnes

- Memoirs of W. W. Holden (1911)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.