Total war

| War |

| History of war |

| Types of War |

| Civil war · Total war |

| Battlespace |

| Air · Information · Land · Sea · Space |

| Theaters |

| Arctic · Cyberspace · Desert Jungle · Mountain · Urban |

| Weapons |

| Armored · Artillery · Biological · Cavalry Chemical · Electronic · Infantry · Mechanized · Nuclear · Psychological Radiological · Submarine |

| Tactics |

|

Amphibious · Asymmetric · Attrition |

| Organization |

|

Chain of command · Formations |

| Logistics |

|

Equipment · Materiel · Supply line |

| Law |

|

Court-martial · Laws of war · Occupation |

| Government and politics |

|

Conscription · Coup d'état |

| Military studies |

|

Military science · Philosophy of war |

Total war is a military conflict in which nations mobilize all available resources in order to destroy another nation's ability to engage in war. Total war has been practiced for centuries, but outright total warfare was first demonstrated in the nineteenth century and flourished with conflicts in the twentieth century. When one side of a conflict participates in total war, they dedicate not only their military to victory, but the civilian population still at home to working for victory as well. It becomes an ideological state of mind for those involved, and therefore, represents a very dangerous methodology, for the losses are great whether they win or lose.

The threat of total devastation to the earth and humankind through nuclear warfare in the mid-twentieth century caused a change in thinking. Such a war does not require the mobilization of the whole population, although it would result in their destruction. Since that time, therefore, the arena of war has retreated to smaller powers, and major powers have not been involved in a total war scenario. However, this has not necessarily reduced the casualties or the suffering of those involved in wars and the threat of widespread violence remains. Ultimately, humankind must move beyond the age of resolving differences through acts of violence, and establish a world in which war, total or otherwise, no longer exists.

Origin and overview

The concept of total war is often traced back to Carl von Clausewitz and his writings Vom Kriege (On War), but Clausewitz was actually concerned with the related philosophical concept of absolute war, a war free from any political constraints, which Clausewitz held was impossible. The two terms, absolute war and total war, are often confused:

Clausewitz's concept of absolute war is quite distinct from the later concept of "total war." Total war was a prescription for the actual waging of war typified by the ideas of General Erich von Ludendorff, who actually assumed control of the German war effort during World War One. Total war in this sense involved the total subordination of politics to the war effort‚ÄĒan idea Clausewitz emphatically rejected, and the assumption that total victory or total defeat were the only options.[1]

Indeed, it is General Erich von Ludendorff during World War I (and in his 1935 book, Der Totale Krieg‚ÄĒThe Total War) who first reversed the formula of Clausewitz, calling for total war‚ÄĒthe complete mobilization of all resources, including policy and social systems, to the winning of war.

There are several reasons for the changing concept and recognition of total war in the nineteenth century. The main reason is industrialization. As countries' natural and capital resources grew, it became clear that some forms of conflict demanded more resources than others. For example, if the United States was to subdue a Native American tribe in an extended campaign lasting years, it still took much less resources than waging a month of war during the American Civil War. Consequently, the greater cost of warfare became evident. An industrialized nation could distinguish and then choose the intensity of warfare that it wished to engage in.

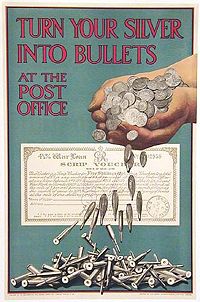

Additionally, this was the time when warfare was becoming more mechanized. A factory and its workers in a city would have greater connection with warfare than before. The factory itself would become a target, because it contributed to the war effort. It follows that the factory's workers would also be targets. Total war also resulted in the mobilization of the home front. Propaganda became a required component of total war in order to boost production and maintain morale. Rationing took place to provide more material for waging war.

There is no single definition of total war, but there is general agreement among historians that the First World War and Second World War were both examples. Thus, definitions do vary, but most hold to the spirit offered by Roger Chickering:

Total war is distinguished by its unprecedented intensity and extent. Theaters of operations span the globe; the scale of battle is practically limitless. Total war is fought heedless of the restraints of morality, custom, or international law, for the combatants are inspired by hatreds born of modern ideologies. Total war requires the mobilization not only of armed forces but also of whole populations. The most crucial determinant of total war is the widespread, indiscriminate, and deliberate inclusion of civilians as legitimate military targets.[2]

Early examples

The first documented total war was the Peloponnesian War, as described by the historian, Thucydides. This war was fought between Athens and Sparta between 431 and 404 B.C.E. Previously, Greek warfare was a limited and ritualized form of conflict. Armies of hoplites would meet on the battlefield and decide the outcome in a single day. During the Peloponnesian War, however, the fighting lasted for years and consumed the economic resources of the participating city-states. Atrocities were committed on a scale never before seen, with entire populations being executed or sold into slavery, as in the case of the city of Melos. The aftermath of the war reshaped the Greek world, left much of the region in poverty, and reduced once influential Athens to a weakened state, from which it never completely recovered.

The Thirty Years War may also be considered a total war.[3] This conflict was fought between 1618 and 1648, primarily on the territory of modern Germany. Virtually all of the major European powers were involved, and the economy of each was based around fighting the war. Civilian populations were devastated. Estimates of civilian casualties are approximately 15-20 percent, with deaths due to a combination of armed conflict, famine, and disease. The size and training of armies also grew dramatically during this period, as did the cost of keeping armies in the field. Plunder was commonly used to pay and feed armies.

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

French Revolution

The French Revolution introduced some of the concepts of total war. The fledgling republic found itself threatened by a powerful coalition of European nations. The only solution, in the eyes of the Jacobin government, was to pour the nation's entire resources into an unprecedented war effort‚ÄĒthis was the advent of the lev√©e en masse. The following decree of the National Convention on August 23, 1793, clearly demonstrates the enormity of the French war effort:

From this moment until such time as its enemies shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the services of the armies. The young men shall fight; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothes and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn linen into lint; the old men shall betake themselves to the public squares in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic.

Taiping Rebellion

During the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) that followed the secession of the T√†ip√≠ng TińĀngu√≥ (Ś§™ŚĻ≥Ś§©Śúč, Wade-Giles T'ai-p'ing t'ien-kuo) (Heavenly Kingdom of Perfect Peace) from the Qing empire, the first instance of total war in modern China can be seen. Almost every citizen of the T√†ip√≠ng TińĀngu√≥ was given military training and conscripted into the army to fight against the imperial forces.

During this conflict, both sides tried to deprive each other of the resources to continue the war and it became standard practice to destroy agricultural areas, butcher the population of cities, and, in general, exact a brutal price from captured enemy lands in order to drastically weaken the opposition's war effort. This war truly was total in that civilians on both sides participated to a significant extent in the war effort and in that armies on both sides waged war on the civilian population as well as military forces. In total, between 20 and 50 million died in the conflict, making it bloodier than the First World War and possibly bloodier than the Second World War as well, if the upper end figures are accurate.

American Civil War

U.S. Army General William Tecumseh Sherman's "March to the Sea" in 1864 during the American Civil War destroyed the resources required for the South to make war. He is considered one of the first military commanders to deliberately and consciously use total war as a military tactic. Also, General Phillip Sheridan's stripping of the Shenandoah Valley was considered "total war." Ulysses S. Grant was the general to initiate the practice in the Civil War.

Twentieth century

World War I

Almost the whole of Europe mobilized to wage World War I. Young men were removed from production jobs and were replaced by women. Rationing occurred on the home fronts.

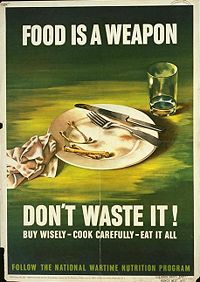

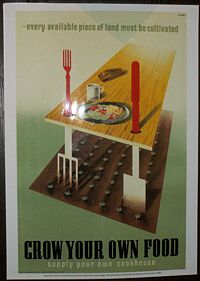

One of the features of total war in Britain was the use of propaganda posters to divert all attention to the war on the home front. Posters were used to influence people's decisions about what to eat and what occupations to take (women were used as nurses and in munitions factories), and to change the attitude of support towards the war effort.

After the failure of the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, the large British offensive in March 1915, the British Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Sir John French claimed that it failed because of a lack of shells. This led to the Shell Crisis of 1915, which brought down the Liberal British government under the Premiership of H.H. Asquith. He formed a new coalition government dominated by Liberals and appointed Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions. It was a recognition that the whole economy would have to be geared for war if the Allies were to prevail on the Western Front.

As young men left the farms for the front, domestic food production in Britain and Germany fell. In Britain, the response was to import more food, which was done despite the German introduction of unrestricted submarine warfare, and to introduce rationing. The Royal Navy's blockade of German ports prevented Germany from importing food, and the Germans failed to introduce food rationing. German capitulation was hastened in 1918, by the worsening food crisis in Germany.

World War II

United Kingdom

Before the onset of the Second World War, the United Kingdom drew on its First World War experience to prepare legislation that would allow immediate mobilization of the economy for war, should future hostilities break out.

Rationing of most goods and services was introduced, not only for consumers but also for manufacturers. This meant that factories manufacturing products that were irrelevant to the war effort had more appropriate tasks imposed. All artificial light was subject to legal blackouts.

Not only were men and women conscripted into the armed forces from the beginning of the war (something which had not happened until the middle of World War I), but women were also conscripted as Land Girls to aid farmers and the Bevin Boys were conscripted to work down in the coal mines.

The Dunkirk evacuation by the British, was the large evacuation of Allied soldiers from May 26 to June 4, 1940, during the Battle of Dunkirk. In nine days, more than three hundred thousand (338,226) soldiers‚ÄĒ218,226 British and 120,000 French‚ÄĒwere rescued from Dunkirk, France, and the surrounding beaches by a hastily assembled fleet of about seven hundred boats. These craft included the famous "Little Ships of Dunkirk," a mixture of merchant marine boats, fishing boats, pleasure craft, and RNLI lifeboats, whose civilian crews were called into service for the emergency. These small craft ferried troops from the beaches to larger ships waiting offshore.

Huge casualties were expected in bombing raids, and so children were evacuated from London and other cities en masse to the countryside for compulsory billeting in households. In the long term, this was one of the most profound and longer lasting social consequences of the whole war for Britain. This is because it mixed up children with the adults of other classes. Not only did the middle and upper classes become familiar with the urban squalor suffered by working class children from the slums, but the children got a chance to see animals and the countryside, often for the first time, and experience rural life.

Germany

In contrast, Germany started the war under the concept of blitzkrieg. It did not accept that it was in a total war until Joseph Goebbels' Sportpalast speech of February 18, 1943. Goebbels demanded from his audience a commitment to total war, the complete mobilization of the German economy and German society for the war effort. For example, women were not conscripted into the armed forces or allowed to work in factories. The Nazi party adhered to the policy that a woman's place was in the home, and did not change this even as its opponents began moving women into important roles in production.

The commitment to the doctrine of the short war was a continuing handicap for the Germans; neither plans nor state of mind were adjusted to the idea of a long war until it was too late. Germany's armament minister, Albert Speer, who assumed office in early 1942, nationalized German war production and eliminated the worst inefficiencies. Under his direction, a threefold increase in armament production occurred and did not reach its peak until late 1944. To do this during the damage caused by the growing strategic Allied bomber offensive is an indication of the degree of industrial under-mobilization in the earlier years. It was because the German economy through most of the war was substantially under-mobilized that it was resilient under air attack. Civilian consumption was high during the early years of the war and inventories both in industry and in consumers' possession were high. These helped cushion the economy from the effects of bombing. Plant and machinery were plentiful and incompletely used, thus it was comparatively easy to substitute unused or partly used machinery for that which was destroyed. Foreign labor, both slave labor and labor from neighboring countries who joined the Anti-Comintern Pact with Germany, was used to augment German industrial labor which was under pressure by conscription into the Wehrmacht (Armed Forces).

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union (USSR) was a command economy which already had an economic and legal system allowing the economy and society to be redirected into fighting a total war. The transportation of factories and whole labor forces east of the Urals as the Germans advanced across the USSR in 1941, was an impressive feat of planning. Only those factories which were useful for war production were moved because of the total war commitment of the Soviet government.

During the battle of Leningrad, newly-built tanks were driven‚ÄĒunpainted because of a paint shortage‚ÄĒfrom the factory floor straight to the front. This came to symbolize the USSR's commitment to the Great Patriotic War and demonstrated the government's total war policy.

To encourage the Russian people to work harder, the communist government encouraged the people's love of the Motherland and even allowed the reopening of Russian Orthodox Churches as it was thought this would help the war effort.

The ruthless movement of national groupings like the Volga German and later the Crimean Tatars (who Stalin thought might be sympathetic to the Germans) was a development of the conventional scorched earth policy. This was a more extreme form of internment, implemented by both the UK government (for Axis aliens and British Nazi sympathizers), as well as the U.S. and Canadian governments (for Japanese-Americans).

Unconditional surrender

After the United States entered World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt declared at Casablanca conference to the other Allies and the press that unconditional surrender was the objective of the war against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan. Prior to this declaration, the individual regimes of the Axis Powers could have negotiated an armistice similar to that at the end of World War I and then a conditional surrender when they perceived that the war was lost.

The unconditional surrender of the major Axis powers caused a legal problem at the post-war Nuremberg Trials, because the trials appeared to be in conflict with Articles 63 and 64 of the Geneva Convention of 1929. Usually if such trials are held, they would be held under the auspices of the defeated power's own legal system as happened with some of the minor Axis powers, for example in the post World War II Romanian People's Tribunals. To circumvent this, the Allies argued that the major war criminals were captured after the end of the war, so they were not prisoners of war and the Geneva Conventions did not cover them. Further, the collapse of the Axis regimes created a legal condition of total defeat (debellatio) so the provisions of the 1907 Hague Conventions over military occupation were not applicable.[4]

Present day

Since the end of World War II, no industrial nations have fought such a large, decisive war, due to the availability of weapons that are so destructive that their use would offset the advantages of victory. With nuclear weapons, the fighting of a war became something that instead of taking years and the full mobilization of a country's resources, such as in World War II, would instead take hours, and the weaponry could be developed and maintained with relatively modest peace time defense budgets. By the end of the 1950s, the super-power rivalry resulted in the development of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), the idea that an attack by one superpower would result in a war of retaliation which could destroy civilization and would result in hundreds of millions of deaths in a world where, in words widely attributed to Nikita Khrushchev, "The living will envy the dead."[5]

As the tensions between industrialized nations have diminished, European continental powers for the first time in 200 years started to question if conscription was still necessary. Many are moving back to the pre-Napoleonic ideas of having small professional armies. This is something which despite the experiences of the first and second world wars is a model which the English speaking nations had never abandoned during peace time, probably because they have never had a common border with a potential enemy with a large standing army. In Admiral Jervis's famous phrase, "I do not say, my Lords, that the French will not come. I say only they will not come by sea."

The restrictions of nuclear and biological weaponry have not led to the end of war involving industrial nations, but a shift back to the limited wars of the type fought between the competing European powers for much of the nineteenth century. During the Cold War, wars between industrialized nations were fought by proxy over national prestige, tactical strategic advantage, or colonial and neocolonial resources. Examples include the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Since the end of the Cold War, some industrialized countries have been involved in a number of small wars with strictly limited strategic objectives which have motives closer to those of the colonial wars of the nineteenth century than those of total war; examples include the Australian-led United Nations intervention in East Timor, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization intervention in Kosovo, the internal Russian conflict with Chechnya, and the American-led coalitions which invaded Afghanistan and twice fought the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein.

Total war, however, is still very much a part of the political landscape. Even with the disarmament of nuclear weapons and biological weapons, total war is still possible. Some consider the genocides in Rwanda and Darfur as acts of total war. The break up of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s also has familiar elements of total war. Civil wars between a nation's own populations can be regarded as total war, especially if both sides are committed wholly to defeating the other side. Total war between industrialized nations is theorized to be non-existent, simply because of the interconnectivity between economies. Two industrialized nations committed in total war would affect much of the world. However, countries in the process of industrializing and countries that have not yet industrialized are still at risk for total war.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Christopher Bassford, Clausewitz in English: The Reception of Clausewitz in Britain and America, 1815-1945 (Oxford University Press, 2002). ISBN 978-0195083835

- ‚ÜĎ Manfred Boemeke, Robert Chickering, Stig Forster, Total War: The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 (1999). ISBN 978-0521622943

- ‚ÜĎ Chris Trueman, Military Developments in the Thirty Years War, History Learning Site. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Ruth Wedgood, Judicial Overreach, Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Nikita Khrushchev, Respectfully Quoted: A Dictionary of Quotations, Columbia Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bassford, Christopher. 2002. Clausewitz in English: The Reception of Clausewitz in Britain and America, 1815-1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195083835

- Bell, David. 2007. The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0618349654

- Boemeke, Manfred, Robert Chickering, and Stig Forster. 1999. Total War: The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914. ISBN 978-0521622943

- Kopf, David and Eric Markusen. 1995. The Holocaust and Strategic Bombing: Genocide and Total War in the Twentieth Century. Westview Press. ISBN 0813375320

- McWhiney, Grady and Daniel Sutherland. 1998. The Emergence of Total War. McWhiney Foundation Press. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- Neely, Mark. 2004. Was the Civil War a Total War? Civil War History. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.