Pangolin

| Pangolins[1]

| ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sunda Pangolin, Manis javanica

| ||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

|

Manis culionensis |

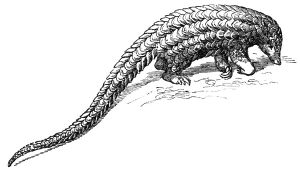

Pangolin, or scaly anteater, is the common name for African and Asian armored mammals comprising the order Pholidota, characterized by a long and narrow snout, no teeth, a long tongue used to capture ants and termites, short and powerful limbs, a long tail, and a unique covering of large, overlapping body scales. There is only one extant family (Manidae) and one genus (Manis) of pangolins, comprising seven or eight species. There are also a number of extinct taxa.

The name "pangolin" derives from the Malay word pengguling ("something that rolls up").

Description

Pangolins are similar in appearance as anteaters in that they have a long and tapered body shape and snout, a very long, worm-like tongue, short and powerful limbs, and no teeth. They likewise are similar in form to armadillos, which have short legs and armor-like jointed plates.

The size of pangolins varies by species, with a head and body length ranging from 30 to 90 centimeters (12 to 35 inches), a tail of from 26 to 88 centimeters (10 to 35 inches), and a weight from about 1 to 35 kilograms (2 to 77 pounds) (Atkins 2004). Females are generally smaller than males. The males may weigh ten to fifty percent more (Atkins 2004).

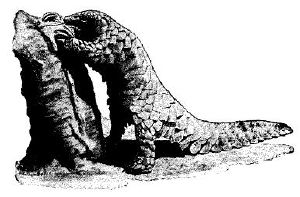

The physical appearance of pangolins is marked by large, hardened, overlapping, plate-like scales covering their skin, making them almost reptilian-looking. The scales, which are soft on newborn pangolins but harden as the animal matures, are made of keratin, the same material of which human fingernails and tetrapod claws are made. Pangolins are distinct among mammals in terms of this unique adaptation of a covering of keratin body scales (Briggs and Briggs 2006; Atkins 2004). (The armor of armadillos is formed by plates of dermal bone covered in small, overlapping epidermal scales.) The pangolin is often compared to a walking pine cone or globe artichoke. It can curl up into a ball when threatened, with its overlapping scales acting as armor and its face tucked under its tail. The scales are sharp-edged, providing extra defense.

The scale color, size, pattern, quantity, and shape varies among the different species and also can differ somewhat among individuals within a species (Atkins 2004). Generally, there are 18 rows of overlapping scales around the body, with scales continuous to the tip of the tail. The African species differ from the Asian by having a double row starting two-thirds of the way to the tip of the tail (Atkins 2004). Coloration can vary from dark brown to yellowish, and include dark olive-brown, pale live, and yellow brown (Atkins 2004). The number of scales remain constant throughout life (Atkins 2004).

Parts of the body without scales (underside of head, sides of face, throat, and neck, stomach, inner sides of limbs, and snout and chin, are thinly covered with hair (Atkins 2004). The Asian species have three or four hairs at the base of each scale, but the African species lack hairs at the base of the scales (Atkins 2004).

The limbs of pangolins are short but powerful and are tipped with sharp, clawed digits; the middle digit is the largest (Atkins 2004). The front claws are large and useful for digging into termite mounds and ant hills. However, the front claws are so long that they are unsuited for walking, and so the animal walks with its fore paws curled over to protect them.

The heads of pangolins are small and tapered, and the eyes are small. Depending on the species, the ears may be rudimentary or absent. The jaw lacks teeth, although embryos have small, temporary, primordial teeth (Atkins 2004).

The tongues of pangolins are extremely elongated, may be round or flattened, and extend into the abdominal cavity. The tongue is unattached from the hyoid bone and extend past the pharynx deep into the thorax, as with the giant anteater and the tube-lipped nectar bat (Chan 1995). This extension lies between the sternum and the trachea. Large pangolins can extend their tongues as much as 40 centimeters (16 inches), with a thickness of only 0.5 centimeters (1/4 inch) (Mondadori 1988). The very large salivary glands coat the tongue with a sticky saliva for capturing insects.

The tail is powerful and mobile, and is fully prehensile in arboreal species, despite being covered with scales (Atkins 2004). The tails of terrestrial species is shorter and more blunt and is not considered fully prehensile (Atkins 2004).

For defensive purposes (in addition to rolling into a ball), pangolins can emit a noxious smelling musky fluid from glands near the anus, similar to the spray of a skunk.

Distribution and habitat

Pangolins have They are found in tropical regions of Africa and Asia.

Behavior and diet

Arboreal pangolins live in hollow trees, whereas the ground dwelling species dig tunnels underground, up to a depth of 3.5 meters (11 feet).[2] Pangolins are also good swimmers.[2]

Pangolins are nocturnal animals, using their well-developed sense of smell to find insects. The long-tailed pangolin is also active by day. Pangolins spend most of the daytime sleeping, curled up into a ball (Mondadori 1988).

In pangolins, the section of the brain that relates to problem solving is highly developed. Although their problem solving ability is primarily used to find food in obscure locations, when kept in captivity pangolins are remarkable escape artists.[citation needed].

Diet

Pangolins lack teeth and the ability to chew. Instead, they tear open anthills or termite mounds with their powerful front claws and probe deep into them with their very long tongues. Pangolins have an enormous salivary gland in their chests to lubricate the tongue with sticky, ant-catching saliva.

Some species, such as the Tree Pangolin, use their strong tails to hang from tree branches and strip away bark from the trunk, exposing insect nests inside.

Reproduction

Gestation is 120-150 days. African pangolin females usually give birth to a single offspring at a time, but the Asiatic species can give birth from one to three.[2] Weight at birth is 80-450 g (3-18 ounces), and the scales are initially soft. The young cling to the mother's tail as she moves about, although, in burrowing species, they remain in the burrow for the first 2-4 weeks of life. Weaning takes place at around three months of age, and pangolins becomes sexually mature at two years.[3]

Threats

Pangolin are hunted and eaten in many parts of Africa and it is one of the more popular types of bush meat. Pangolins are also in great demand in China because their meat is considered a delicacy and some Chinese believe pangolin scales reduce swelling, promote blood circulation and help breast-feeding women produce milk. This, coupled with deforestation, has led to a large decrease in the numbers of Giant Pangolins.

Pangolin populations have suffered from illegal trafficking. In May 2007, for example, Guardian Unlimited reported that 31 pangolins were found aboard an abandoned vessel off the coast of China. The boat contained some 5,000 endangered animals.

The Guardian recently provided a description of the killing and eating of pangolins: "A Guangdong chef interviewed last year in the Beijing Science and Technology Daily described how to cook a pangolin: 'We keep them alive in cages until the customer makes an order. Then we hammer them unconscious, cut their throats and drain the blood. It is a slow death. We then boil them to remove the scales. We cut the meat into small pieces and use it to make a number of dishes, including braised meat and soup. Usually the customers take the blood home with them afterwards.'" [4]

On November 10, 2007, Thai customs officers announced that they had rescued over 100 pangolins as the animals were being smuggled out of the country, en route to China, where they were to be sold for cooking. [5]

Taxonomy

Pangolins are placed in the order Pholidota. They have been classified with various other orders, for example Xenarthra, which includes the ordinary anteaters, sloths, and the similar-looking armadillos. But newer genetic evidence (Murphy et al. 2001), indicates that their closest living relatives are the Carnivora, with which they form a clade, the Ferae (Beck et al. 2006). Some paleontologists have classified the pangolins in the order Cimolesta, together with several extinct groups.

- ORDER PHOLIDOTA

- Family †Epoicotheriidae

- Family †Metacheiromyidae

- Family Manidae

- Subfamily †Eurotamanduinae

- Genus †Eurotamandua

- Subfamily Maninae

- Genus †Cryptomanis

- Genus †Eomanis

- Genus †Necromanis

- Genus †Patriomanis

- Genus Manis

- Subgenus Manis

- Indian Pangolin (M. crassicaudata)

- Chinese Pangolin (M. pentadactyla)

- Subgenus Paramanis

- Sunda Pangolin (M. javanica)

- Philippine Pangolin (M. culionensis)

- Subgenus Smutsia

- Giant Pangolin (M. gigantea)

- Ground Pangolin (M. temmincki)

- Subgenus Phataginus

- Tree Pangolin (M. tricuspis)

- Subgenus Uromanis

- Long-tailed Pangolin (M. tetradactyla)

- Subgenus Manis

- Subfamily †Eurotamanduinae

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Schlitter, D. A. 2005. In D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder, eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd edition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801882214.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMondadori - ↑ Dickman, Christopher R. (1984). in Macdonald, D.: The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File, 780-781. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ↑ Watts, Jonathan (2007-05-26), "'Noah's Ark' of 5,000 rare animals found floating off the coast of China", The Guardian

- ↑ 2007-11-10, Thailand saves pangolins bound for China restaurants, AFP. Retrieved 2007-11-11

- Atkins, W. A. 2004. Pholidota pangolins (Manidae). Pages 107 to 120 in B. Grzimek, D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M. C. McDade (eds.), Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, volume 16. Detroit: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0787657921.

.[1] A higher-level MRP supertree of placental mammals

Beck, R. M. D., O. R. P. Bininda-Emonds, M. Cardillo, F.-G. R. Liu, and A. Purvis. 2006. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2006, 6:93doi:10.1186/1471-2148-6-93

.[3]

External links

- Pangolin: Wildlife summary from the African Wildlife Foundation

- A photograph of a pangolin

- Tree of Life of Pholidota

| Mammals |

|---|

| Monotremata (platypus, echidnas) |

|

Marsupialia: | Paucituberculata (shrew opossums) | Didelphimorphia (opossums) | Microbiotheria | Notoryctemorphia (marsupial moles) | Dasyuromorphia (quolls and dunnarts) | Peramelemorphia (bilbies, bandicoots) | Diprotodontia (kangaroos and relatives) |

|

Placentalia: Cingulata (armadillos) | Pilosa (anteaters, sloths) | Afrosoricida (tenrecs, golden moles) | Macroscelidea (elephant shrews) | Tubulidentata (aardvark) | Hyracoidea (hyraxes) | Proboscidea (elephants) | Sirenia (dugongs, manatees) | Soricomorpha (shrews, moles) | Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs and relatives) Chiroptera (bats) | Pholidota (pangolins)| Carnivora | Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) | Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) | Cetacea (whales, dolphins) | Rodentia (rodents) | Lagomorpha (rabbits and relatives) | Scandentia (treeshrews) | Dermoptera (colugos) | Primates | |

Template:Pholidota

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ BioMed Central | Full text | A higher-level MRP supertree of placental mammals

- ↑ (2006) The Encyclopedia of World Wildlife. Paragon Books, p63.

- ↑ Chan, Lap-Ki (1995). Extrinsic Lingual Musculature of Two Pangolins (Pholidota: Manidae). Journal of Mammalogy 76 (2): 472–480.

- ↑ (1988) in Mondadori, Arnoldo Ed.: Great Book of the Animal Kingdom. New York: Arch Cape Press, p252.

- ↑ Murphy, Willian J., et al (2001-12-14). Resolution of the Early Placental Mammal Radiation Using Bayesian Phylogenetics. Science 294 (5550): 2348–2351.