King, Martin Luther, Jr.

| (154 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} |

| − | {{ | + | {{epname|King, Martin Luther, Jr.}} |

| − | {{ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

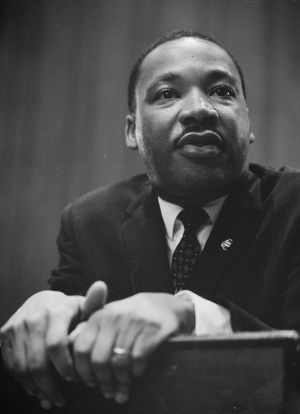

| − | + | [[Image:Martin-Luther-King-1964-leaning-on-a-lectern.jpg|thumb|300px|Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King addressing the press in 1964. "An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind".]] | |

| − | + | The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929–April 4, 1968) was America's foremost civil rights leader and is deemed by many as the greatest American leader of the twentieth century. His leadership was fundamental to ending legal [[segregation]] in the [[United States]] and empowering the African-American community. A moral leader foremost, he espoused [[nonviolent resistance]] as the means to bring about political change, emphasizing that spiritual principles guided by love can triumph over politics driven by hate and fear. He was a superb orator, best known for his "I Have a Dream" speech given at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. King became the youngest person to win the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] in 1964. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | At age 39, he was killed by an assassin's bullet in 1968. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s impact and legacy was not limited to the U.S., but was worldwide, including influencing the struggle against [[apartheid]] in [[South Africa]]. Honored on [[Martin Luther King, Jr. Day]], the third Monday in January close to his birthday, King is only one of three Americans to have a national holiday, and the only African-American. | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| + | Martin Luther King, Jr. combined the qualities that propelled him to world-figure-hero status during the course of his life. No other scholar-activist, except possibly [[Mahatma Gandhi]], did as fine a job of descending from the lofty level of the ivory tower and walking among the masses, meeting them at their level, giving voice to their yearnings, and exemplifying the common touch. Comfortable in his own skin and confident in the righteousness of his cause, King still grappled daily with the doubts, struggles, and temptations that inevitably burden all leaders. Stephen B. Oates tells us that: | ||

| + | <blockquote>Like everybody, King had imperfections: he had hurts and insecurities, conflicts and contradictions, guilts and frailties, a good deal of anger, and he made mistakes. …his achievements… were astounding for a man who was cut down at the age of only 39 and who labored against staggering odds—not only the bastion of segregation that was the American South of his day, but the monstrously complex racial barriers of the urban North, a hateful FBI crusade against him, a lot of jealousy on the part of rival civil-rights leaders and organizations, and finally the Vietnam War and a vengeful [[Lyndon B. Johnson|Lyndon Johnson]]. King was all things to the American Negro movement—advocate, orator, field general, historian, fund raiser, and symbol. Though he longed to be a teacher and scholar on the university level, he became instead a master of direct-action protest, using it in imaginative and unprecedented ways to stimulate powerful federal legislation that radically altered Southern race relations.<ref> Stephen B. Oates, ''Let the Trumpet Sound: Life of Martin Luther King, Jr.'' (New York, NY: HarperPerennial, 1994, ISBN 978-0060924737), x.</ref> </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Despite his flaws, King maintained an attitude of public-minded, self-sacrificial service, which was the hallmark of both his impressively enlightened [[Christianity|Christian]] faith and his lifestyle of [[prayer]], perseverance, and contemplation. | |

| − | + | {{readout||right|250px|Martin Luther King, Jr. received the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] in 1964 for his work to end racial segregation through nonviolent means; at the time he was the award's youngest recipient}} | |

| − | + | Before the end of his life, he had (1) become the third black and the youngest person to ever receive the [[Nobel Peace Prize]]; (2) established himself as the chief architect and premiere spokesperson for the [[African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)|Civil Rights Movement of 1955-1968]]—an authentically religious revival, the socio-political impact of which was unprecedented in human history; (3) been jailed for a total of twenty-nine times, in the name of freedom and justice; (4) witnessed, first hand, the death of the wickedly racist [[Jim Crow Laws|Jim-Crow]] system of legal segregation in the South; and (5) led the Civil Rights struggle on its march toward inspiring the [[United States]] of America to earnestly practice the truths found in the [[Bible]], which stands as the cornerstone of its republican form of government. He was posthumously awarded the [[Presidential Medal of Freedom]] by [[Jimmy Carter]], in 1977, and the [[Congressional Gold Medal]] in 2004. In 1986, during the administration of President [[Ronald Reagan]], [[Martin Luther King, Jr. Day|Martin Luther King Day]] was established in his honor. King's most influential and well-known public address is his world-renowned "I Have A Dream" speech, delivered at the Lincoln Memorial, on August 28, 1963. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Before the end of his life, he had become the third black and the youngest person to ever receive the Nobel Peace Prize; | ||

| − | |||

| − | Through intense study and masterfully systematic thought, King successfully merged his intimate knowledge of the [[Declaration of Independence (United States)|Declaration of Independence]], the [[United States Constitution|U.S. Constitution]], the | + | Through intense study and masterfully systematic thought, King successfully merged his intimate knowledge of the [[Declaration of Independence (United States)|Declaration of Independence]], the [[United States Constitution|U.S. Constitution]], the Mayflower Compact, and other documents, with his strikingly insightful, biblical worldview. As a result, he ultimately forged within himself an undying love for America and a passion for its destiny. That passion fueled his vision and instilled his being with a flaming religious commitment. It was this committed life that made it possible for him to become both a sterling example of sacrificial leadership and a providential instrument of the most noble [[Christianity|Judeo-Christian]] ideals. And it was that model of leadership that fueled the Civil Rights Movement in its nearly successful effort at inciting a Christian Revolution within the borders of the United States. |

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| + | ===Birth, early life, and education=== | ||

| + | '''Martin Luther King, Jr.''' was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, the second child and first son of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr., and Mrs. Alberta Williams King. Reverend King—the boy's father—was pastor of black Atlanta's historical, influential, and prestigious Ebenezer Baptist Church. As such, the Rev. King was likewise a pillar in Atlanta's black middle class. He ruled his household with a fierceness not unlike that of an Old Testament patriarch, and he provided a lifestyle in which his children were disciplined, protected, and very well provided for. By the Reverend King's decree, his son (Martin Luther King, Jr.), during the course of his youth, went by the name "M.L." A strong and healthy newborn, M.L. had been preceded in birth by his sister, Willie Christine, and was followed by his brother, Alfred Daniel, or A.D. Within the context of his rearing, and because he was his father's son, the church was M.L.'s second home. It functioned as the hub around which the wheel of King family life rotated. And the sanctuary was located only three blocks away from the big house on Auburn Avenue. Having been slipped, by his parents, into grade school a year early, and having been bright and gifted enough to skip a number of grades along the way, M.L. entered Booker T. Washington High School in 1942, at the age of 13. Two years later, as an exceptional high school junior, he passed Morehouse College's entrance exam, graduated from Booker T. Washington after the eleventh grade, and, at the age of 15, enrolled in Morehouse. There, he was mentored by the school's president, civil rights veteran [[Benjamin Mays]]. King graduated from Morehouse in 1948, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in [[Sociology]]. He subsequently enrolled at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was elected student-body president, and from where he later graduated as class valedictorian, with a Bachelor of Divinity degree, in 1951.<ref>Frederick L. Downing, ''To See the Promised Land: The Faith Pilgrimage of Martin Luther King, Jr.'' (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0865542075), 150.</ref> | ||

| − | + | In 1955, he received a Doctor of Philosophy in Systematic Theology from [[Boston University]]. Thus, from the age of 15 until 26, King embarked upon a pilgrimage of intellectual discovery. Through it, he systematized a religious and social worldview, characterized by unusually striking insights and by an unshakable adherence to the power of [[nonviolence]] and redemption through unearned [[suffering]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Marriage and family life=== |

| − | + | Following a whirlwind, 16-month courtship, Martin Luther King, Jr., married [[Coretta Scott King|Coretta Scott]], on June 18, 1953. King's father performed the wedding ceremony at the residence of Scott's parents in Marion, Alabama. | |

| − | + | Martin and Coretta Scott King were the parents of four children: | |

| − | + | *Yolanda Denise (b. November 17, 1955, Montgomery, Alabama; d. May 15, 2007) | |

| + | *Martin Luther III (b. October 23, 1957, Montgomery, Alabama) | ||

| + | *Dexter Scott (b. January 30, 1961, Atlanta, Georgia) | ||

| + | *Bernice Albertine (b. March 28, 1963, Atlanta, Georgia) | ||

| − | + | All four children followed in their father's footsteps as civil rights activists, although their opinions differ on a number of controversial issues. Coretta Scott King passed away on January 30, 2006. | |

| − | + | ==Career and civil rights activism== | |

| − | [[ | + | The best way to understand the impact of King's 13-year crusade for freedom and justice is to divide his career into two periods—before the Selma, Alabama campaign and after it. The first period ignited with the [[Montgomery Bus Boycott]] of December 1955 and closed with the successful voting-rights march from Selma to Montgomery, on March 25, 1965. The second period commenced with the January 1966 [[Chicago]] campaign for jobs and slum elimination and ended with the [[assassination]] of King on April 4, 1968, in [[Memphis]]. During the first period, King's belief in divine justice and his vision of a new [[Christian]] social order fueled his sublime oratory and his equally sublime courage. This resulted in a shared commitment to the concept of "'''noncooperation with evil'''," that swept the ranks of [[Civil Rights Movement]] devotees. Through [[nonviolent resistance|nonviolent]], passive resistance, they protested the social evils and injustices of segregation and refused to obey and/or comply with unjust and immoral [[Jim Crow laws]]. The subsequent beatings, jailings, abuses, and violence that were heaped upon these protesters ultimately became the price they paid for unprecedented victories. |

| − | + | ===The Montgomery Bus Boycott=== | |

| + | This campaign lasted from December 2, 1955 until December 21, 1956, and it culminated with the [[Supreme Court of the United States|Supreme Court]]'s declaration that Alabama's system of bus segregation was unconstitutional. On the heels of the courageous stand by Mrs. [[Rosa Parks]] and against the subsequent backlash of white hatred and violence, King's leadership had wrought a stunning triumph, as Montgomery blacks displayed bravery, conviction, solidarity, and noble adherence to Christian principles, and ultimately achieved their goal of desegregating the city's buses. And through this victory, King and his ecclesiastical colleagues elevated to new heights the historic role of the black clergyman as the leader in the quest for [[civil rights]]. | ||

| − | + | ===Birth of the SCLC=== | |

| + | In the aftermath of the victorious Montgomery effort, King recognized the need for a mass movement that would capitalize on the success. The [[Southern Christian Leadership Conference]] (SCLC) was organized on August 7-8, 1959, and King was unanimously elected as president. This was an organization that brought a significantly different focus to the already established mix of the major civil-rights groups. According to Oates: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>SCLC's main goal was to bring the Negro masses into the freedom struggle by expanding the "Montgomery way" across the South....SCLC's initial project was a South-wide voter registration drive called the "Crusade for Citizenship," to commence on Lincoln's birthday, 1958, and to demonstrate once again that "a new Negro," determined to be free, had emerged in America.<ref>Oates, 119.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Stride Toward Freedom=== |

| − | + | Along with his best friend, the Rev. [[Ralph D. Abernathy]], King met with Vice President [[Richard M. Nixon]] on June 13, 1957. A year later, on June 23, 1958, King, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, and Lester Granger met with President [[Dwight D. Eisenhower]]. The SCLC leader was ultimately repulsed by both Nixon and Eisenhower, and King finally gave up on the idea of working with either of them. From 1957-1959, King struggled to (1) keep the ranks of the [[Civil Rights Movement]] unified; (2) raise desperately needed funds; (3) systematize and disseminate the theory and practice of [[nonviolence]]; and (4) establish himself as an incisively competent author. Among other black leaders, there was jealousy of King and his popularity. But this was an issue in which the press did not take much interest. When King's first book, ''Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story,'' hit bookstores, the SCLC leader's prestige skyrocketed as he proclaimed to the world: "To become the instrument of a great idea is a privilege that history gives only occasionally. [[Arnold Toynbee]] says in ''A Study of History,'' that it may be the Negro who will give the new spiritual dynamic to Western civilization that it so desperately needs to survive."<ref> Oates, 129.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | King was extolled by ''Christian Century'' as the leader who had guided his people to unlock "the revolutionary resources of the gospel of Christ."<ref> Oates, 133.</ref> | |

| − | + | Following the September 20, 1958 stabbing attempt on his life by the demented Mrs. Izola Curry, King endeared himself, nationwide, to millions of both black and white Americans, when he forgave the woman and refused to press charges against her. Resigning from the pastorate of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church on November 29, 1959, the SCLC leader spent the next three years watching historic events unfolding in city after city throughout the South. In 1960, he returned to his native city of Atlanta and became co-pastor, with his father, at Ebenezer Baptist Church. From this platform, he sought to advance his SCLC and [[Civil Rights Movement]] agendas, while striving to ensure cooperation and harmony among the SCLC, the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People|NAACP]], and the National Urban League. In the meantime, scores of protesters increasingly joined in uttering the battle cry of "Remember the teachings of [[Jesus of Nazareth|Jesus]], [[Mahatma Gandhi|Gandhi]], and Martin Luther King." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Throughout the year of 1960, King was encouraged by the startlingly pleasant development of student sit-in demonstrations across the South. With black students on numerous campuses now joining in the struggle, the SCLC president was delighted. And as the sit-ins spread, King boldly and unequivocally declared his full-fledged endorsement of their strategic courage in the quest to desegregate eating facilities in Southern cities. When the sit-ins broke out in Atlanta, King lent his voice to the local students' determination, as he penned for the nation at large a defense and an interpretation of the student activism: "A generation of young people has come out of decades of shadows to face naked state power; it has lost its fears, and experienced the majestic dignity of a directed struggle for its own liberation. These young people have connected up with their own history—the slave revolts, the incomplete revolution of the Civil War, the brotherhood of colonial colored men in Africa and Asia. They are an integral part of the history which is reshaping the world, replacing a dying order with a modern democracy."<ref> Oates, 148.</ref> | |

| − | + | On Wednesday, October 19, 1960, King was arrested along with 33 young people who were protesting segregation at the lunch counter of Rich's Snack Bar in an Atlanta department store. Although charges were dropped and the jailed students were all set free, the SCLC leader remained imprisoned. Through trumped-up charges and judicial chicanery, King was convicted of violating his probation regarding a minor traffic offense committed several months earlier, and he was sentenced to four months hard labor in Reidsville State Penitentiary, three hundred miles from Atlanta. The volatile combination of widespread concern for King's safety; public outrage over Georgia's flouting of legal procedure; and the failure of President Dwight Eisenhower to intervene, catapulted the case to national proportions. It was only after the intercession by Democratic presidential candidate [[John F. Kennedy]] that the SCLC leader was released, on October 28. Throughout the black community across the nation, Kennedy's action was so widely publicized that historians generally agree this episode garnered crucial black votes for him and contributed substantially to his slender election victory some eight days later. | |

| − | Throughout | + | Throughout 1961, King witnessed and lauded the development of the method known as Freedom Rides, a technique launched across the South to confront and topple the practice of racially segregated interstate bus facilities. The practice of Freedom Riding proved to be a nightmarishly dangerous and deadly mission that elicited great sacrifice and bloodshed. Yet this was the reason that it was ultimately a spectacular success. "As it turned out, the Freedom Rides dealt a death blow to Jim Crow bus facilities. At (Attorney General) [[Robert Kennedy]]'s request, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), that September, issued regulations ending segregated facilities in interstate bus stations; their regulations were to take effect on November 1, 1961."<ref> Oates, 173.</ref> The victories achieved from the blood, sweat, and tears offered on the altars of sit-ins and Freedom Rides emboldened King to issue his clarion call for all Americans to join these black, white, brown, Jewish, Protestant, and Catholic students in a campaign to forever rid the nation of Jim Crow. Thus, the momentum of the years from 1961-1965 lifted King's influence to its zenith. |

| − | + | Through the Bible-based tactics of applied nonviolence (protest marches, sit-ins, and Freedom Rides), committed allegiance was educed from scores of blacks and sincere whites across the country. Support likewise came from the administrations of Presidents Kennedy and [[Lyndon B. Johnson]]. Advancement took place, despite constant suffering, setbacks, and even notable failures such as at Albany, Georgia (1961-1962), where the movement was utterly and resoundingly defeated in its campaign to desegregate public parks, pools, lunch counters, and other facilities. Taking stock of their failure, King and his lieutenants concluded that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had sided with the Albany segregationists. Despite blacks' repeated complaints regarding the violation of their civil rights, FBI agents had shown absolutely no interest whatsoever. In his statement to the press, the SCLC leader declared: "One of the greatest problems we face with the FBI in the South is that the agents are white Southerners who have been influenced by the mores of their community. To maintain their status, they have to be friendly with the local police and people who are promoting segregation. Every time I saw FBI men in Albany, they were with the local police force."<ref> Oates, 194.</ref> | |

| − | + | Incensed by these remarks, FBI officials—Director [[J. Edgar Hoover]] in particular—angrily determined to make King pay the full price for his "sinister audacity" to criticize them, the accuracy of King's assessment notwithstanding. | |

| − | + | Albany highlighted for King the rigidity and defensiveness of the white South, with regard to the race issue. The SCLC president grew so distressed that he seriously entertained thoughts of quitting the [[Civil Rights Movement]]. A tempting proposal came to him from Sol Hurok's agency, offering him the position of its chief, around-the-world lecturer, with a guaranteed salary of $100,000/year. King grappled with the idea, finally told them no, and, with reawakened resolution, committed himself to the Movement.<ref> Oates, 198.</ref> | |

| − | + | From a procession of speeches and published articles during the late fall and early winter of 1962, King forged a new determination. From his conversations with Alabama's Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth—the head of SCLC's Birmingham auxiliary, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR)—the SCLC leader conceived a strategy whereby a victorious direct-action campaign in Birmingham would make up for the debacle in Albany and would break the back of legal segregation in Birmingham once and for all. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Letter From Birmingham Jail=== |

| − | + | The four-month span from February through May 1963 found King, Shuttlesworth, Abernathy, and others drawing nationwide attention to Birmingham, with their campaign to deracinate the city's stringent segregation policies and expose to the world the viciousness and violence of this community's segregationists. Racism at lunch counters and in hiring practices was ugly enough. Now, added to the humiliation, was the brutality displayed by Police Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor, whose officers unleashed dogs and firehoses upon the peaceful demonstrators. And King was resolved that, in the streets of Birmingham, he and his people would awaken the moral conscience of America. In his own words: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>We must say to our white brothers all over the South who try to keep us down: we will match your capacity to inflict suffering with our capacity to endure suffering. We will match your physical force with soul force. We will not hate you. And yet we cannot, in all good conscience, obey your evil laws. Do to us what you will. Threaten our children and we will still love you…. Say that we're too low, that we're too degraded, yet we will still love you. Bomb our homes and go to our churches early in the morning and bomb them, if you please, and we will still love you. We will wear you down by our capacity to suffer. In winning the victory, we will not only win our freedom. We will so appeal to your heart and your conscience that we will win you in the process.<ref>Oates, 228-229.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | Along with vast numbers of his supporters, including hundreds of schoolchildren, the SCLC leader was arrested and jailed. Notably, among King's supporters, the black clergy of Birmingham were nowhere to be found. And the white clergy had issued a strong statement entreating blacks to not support the demonstrations, and to, instead, press their case in the courts. That statement had been signed by eight white Christian and Jewish clergymen of Alabama. From his Birmingham jail cell, King penned a highly eloquent response that articulated his philosophy of civil disobedience: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>You may well ask, 'Why direct action, why sit-ins, marches, etc.? Isn't negotiation a better path?' You are exactly right in your call for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and establish such creative tension that a community that has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks to so dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored…. History is the long and tragic story of the fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily…. We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.<ref>Richard D. Heffner, ''A Documentary History of the United States'' (New York, NY: Signet, 1991, ISBN 0451207483), 334, 335.</ref><ref name=Letter> Martin Luther King, Jr., [https://www.csuchico.edu/iege/_assets/documents/susi-letter-from-birmingham-jail.pdf Letter from Birmingham Jail] August, 1963. Retrieved January 18, 2023.</ref></blockquote> | |

| + | By mid-May, after three days of around-the-clock negotiations, the demonstrators and the white power structure came to agreements. All of the movement's demands were met. In front of a packed press conference, King and Shuttlesworth stated: "The city of Birmingham has reached an accord with its conscience. Birmingham may well offer for Twentieth Century America an example of progressive racial relations; and for all mankind a dawn of a new day."<ref> Oates, 233.</ref> | ||

| − | King | + | ===Walk To Freedom=== |

| + | Sixty-six days before the famed March on Washington, King was in [[Detroit, Michigan]], at the request of his ecclesiastical colleague, the Rev. C.L. Franklin. Franklin was part of an alliance that included the influential, local black millionaire, James Del Rio, and other members of the Detroit Council for Human Rights. These activists were determined to engineer a huge Kingian breakthrough in the North, and subsequently open up a new Northern front, by orchestrating a massive demonstration of support. As a thriving labor town for blacks, Detroit possessed a solid black middle class that had blossomed from the workforce of its automobile factories. Organized by the esteemed local newspaper journalist, Tony Brown, Detroit's "Walk to Freedom With Martin Luther King, Jr." ensued on June 23, 1963, along the city's Woodward Avenue. Marching in step with the SCLC president, a throng of some 250,000 - 500,000 people moved as one united wave of humanity. The march ended at Covall Hall Auditorium, where King took the stage, and, surrounded by a packed house of listeners, launched into the "I Have A Dream" address that he would also deliver sixty-six days later at the [[Lincoln Memorial]]. The June 29, 1963 edition of ''Business Week'' magazine praised the event as extraordinary. King was lauded as the incarnate messenger of nonviolence. And at the time of the Detroit march, he was ascending daily in his credibility, following the success of the Birmingham campaign. Media coverage of the Detroit march was lavish, once again reiterating the lesson King had learned from the Freedom Rides of the South: attaining authentic success in civil rights efforts mandated doing something dramatic enough to elicit national media attention. Of all the black leaders of his generation, none learned that lesson as well as the SCLC president had. | ||

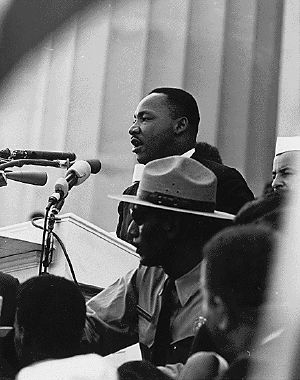

| − | + | [[Image:Martin Luther King - March on Washington.jpg|thumb|right|300px|King is perhaps most famous for his "I Have a Dream" speech, given in front of the [[Lincoln Memorial]] during the August 28, 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.]] | |

| − | Abernathy | + | ===The Dream=== |

| + | Arriving in [[Washington, D.C.]] on August 27, the day before the great march, King and [[Coretta Scott King|Coretta]] entered their suite at the Willard Hotel, and the SCLC president began working on his speech. With support from [[Walter Fauntroy]], [[Andrew Young]], [[Wyatt T. Walker]], and [[Ralph Abernathy]], King toiled throughout the night. According to King biographer, Stephen B. Oates: "Two months ago, in Detroit, he had talked about his dream of a free and just America. But he doubted he could elucidate on that theme in only a few minutes. He elected instead to talk about how America had given the Negro a bad check, and what that meant in light of the [[Emancipation Proclamation]]."<ref> Oates, 249-250.</ref> On August 28, 1963, before a throng of at least 250,000 people, the emotional power and prophetic ring of King's oratory uplifted the crowds, as the rally crescendoed to its conclusion. And he made the point that blacks could wait no longer—that the time of patiently waiting for America to do right by the black man was over: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of ''now''….''Now'' is the time to make real the promises of Democracy. ''Now'' is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. ''Now'' is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. ''Now'' is the time to make justice a reality for all God's children."<ref> Oates, 252.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | The biblical phraseology did its work. Later, when asked about her recollection of the address, Coretta Scott King remarked, "At that moment, it seemed as if the Kingdom of God appeared. But it only lasted for a moment."<ref>James Melvin Washington, ''Testament of Hope: The essential writings and speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr.'' (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991, ISBN 0060646918), 217.</ref> | |

| − | < | ||

| − | + | King's fame and celebrity were now at their peak. To the public, he was the [[symbol]] of a coalition of conscience on the [[civil rights]] issue. But the white racial hostility was not gone, and on Sunday morning, September 15, Birmingham's Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was rocked by a dynamite bomb, that killed four young girls. At a joint funeral service for three of them, King gave the eulogy. Not one single member of Birmingham's white, city officialdom attended the service. The only whites present were a few courageous ministers. Sixty-eight days after the church bombing, on Friday, November 22, President [[John F. Kennedy]] was dead at Dallas' Parkland Hospital, the victim of a sniper's bullet. King joined the rest of the nation in a period of mournful soul searching, stating to Coretta and to Bernard Lee, "This is what is going to happen to me also. I keep telling you, this is a sick nation. And I don't think I can survive either."<ref> Oates, 263.</ref> | |

| − | + | As the year of 1963 came to an end, the SCLC leader was riding the wave of unprecedented fame. He was now the first [[African American|American black]] to ever win the honor of [[TIME Magazine|''TIME'' magazine]]'s "Man of the Year" award. He had displayed exemplary physical courage in the face of danger, and he had been borne to glory on the wings of his "I Have A Dream" speech. Now he was at the center of a rising tide of [[civil rights]] progress that was strongly impacting national and international opinion. The result was the passage of the [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]], a legislative hammer that empowered the national government to outlaw discrimination in publicly-owned facilities and to enforce the desegregation of public accommodations. As the eventful year of 1964 came to a close, King placed the exclamation point at the end of it by becoming the youngest recipient ever of the [[Nobel Peace Prize]], on December 10, in Oslo, Norway. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Selma and Chicago=== | |

| + | The plans for "Project Alabama" were on the table by Christmas time 1964. The goal was the dramatization of the need for a federal voting-rights law that would put legal muscle behind the enfranchisement of blacks in the South. From January until March 1965, the protest marches and demonstrations let Selma know that the SCLC leader and his followers were serious and were playing for keeps. During King's pilotage of the Selma Movement, the city received a visit from [[Malcolm X]], who had flown in, addressed a gathering at Brown Chapel, given Coretta a message for King, and had then departed. Two weeks later, Malcolm X would be assassinated by blacks in New York City. | ||

| − | + | King's imprisonment in Selma, on February 1, 1965, had attracted the national media as well as the attention of the Johnson White House, as blacks struggled to make the right to vote a reality for themselves and all Americans. | |

| − | + | On March 7, a procession from Selma to the State Capitol building in Montgomery commenced. King did not lead it himself, as he was in Atlanta. The marchers encountered state troopers who were armed with tear gas, billy clubs, bullwhips, and rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire. Using these weapons, the troopers attacked the defenseless, nonviolent demonstrators with such viciousness and wrath that by the end of the ordeal, 70 blacks had been hospitalized and an additional 70 treated for injuries. That night, the country was shaken by the news of this brutality in a way that it had never been shaken before, as a film clip of Selma's "Bloody Sunday" interrupted the broadcast of ABC Television's Sunday-night movie, ''Judgment at Nuremburg''. The national outcry was deafening, and public opinion sided with the battered protesters. With a surge of public sympathy now shoring up his Selma Movement, King led a second march on March 9. The procession of 1,500 black and white protesters walked across the Pettus Bridge until it was stopped by a wall of highway patrol officers. The protesters were ordered to abort their march. King objected, but to no avail. The SCLC leader decided at that point to not move forward and force a confrontation. Instead, he led his followers in kneeling to pray and then, surprisingly, turning back. Angered by this decision were many of the young Black Power radicals who already viewed King as being too cautious and overly conservative. These radicals withdrew their moral support. Nevertheless, the nation was now aroused, as events in Selma sparked wide-scale outrage and resulted in the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. On March 25, King and some 25,000 of his followers concluded a four-day, victorious, Selma-to-Montgomery march, escorted by 800 federal troops. Among blacks, the SCLC president now enjoyed the status of a "new [[Moses]]," anointed to lead America on a modern-day Exodus to a new Canaan. | |

| − | + | His moral authority, vision, clout, and credibility notwithstanding, King was unable to allay the impatience blacks now felt at the lack of greater substantive economic and social progress. Such frustration was the root of growing black militancy and the rising popularity of the Black Power Movement. With his Bible-based philosophy of nonviolence under ever-increasing attack, the SCLC leader searched for a way to meet the challenges of the ghetto and its concomitant despair. At the beginning of 1966, King and his forces embarked upon a drive against racial discrimination in Chicago, Illinois. Their chief target was to be segregation in housing. Tremendous media interest was generated by King's entry into Chicago. After a spring and a summer of protest and civil disobedience, the protesters and the city signed an agreement—a document which ultimately turned out to be essentially worthless. The impression remained that King's Chicago campaign ended up null and void, due to the opposition from the city's powerful mayor, Richard J. Daley, as well as due to the poorly understood complexities that characterized Northern racism. | |

| − | King | + | ===Challenges=== |

| + | In the North as well as in the South, [[Black Power]] enthusiasts were challenging and deriding King's thought and his methods. He therefore sought to broaden his appeal by including controversial issues beyond the realm of racial politics that were no less detrimental to black people's progress. These included his irrevocable opposition to the United States' involvement in the [[Vietnam War]] and his vision of a poor people's coalition that would embrace all races and would target economic problems such as [[poverty]] and [[unemployment]]. The SCLC president was hitting one ideological dead end after another, and he was now in search of theories and analyses that would be relevant to the deeper problems he was currently running up against. As he stated to journalist David Halberstam: | ||

| + | <blockquote>For years, …I labored with the idea of reforming the existing institutions of the South, a little change here, a little change there. Now I feel quite differently. I think you've got to have a reconstruction of the entire society—a revolution of values.<ref> Oates, 426.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | This challenge to remain relevant and at the cutting edges of the issues kept King under the relentless bombardment of pressure. The [[Anti-War Movement]] and the [[riot]]s of 1967 only added to the philosophical and spiritual struggles. The SCLC leader sensed, excruciatingly, that "something else had to be found within the arsenal of nonviolence—a new approach that would salvage nonviolence as a tactic, as well as dramatize the need for jobs and economic advancement of the poor."<ref> Oates, 432.</ref> | |

| − | + | Excoriated by critics on the left and the right for his anti-war stance, King strove to keep his sights on the plight of the poor. He was increasingly faced with the limitations of his own worldview, and yet he was committed to elevate and enhance his service to humanity. | |

| − | + | "In a 'Christian Sermon on Peace,' aired over the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation on Christmas Eve 1967 and delivered in person at [[Ebenezer Baptist Church]], King called for a total reconstruction of society for the benefit of white and colored peoples the world over. Human life, he warned, could not survive unless human beings went beyond class, tribe, race, and nation, and developed a world perspective."<ref> Oates, 436.</ref> | |

| − | King | + | Meanwhile, the [[FBI]] stepped up its persecution of King. There were contracts on his life, with assassination threats from the [[Ku Klux Klan]] and other hate groups that had him pinpointed for violence. However, King found the strength to persevere, and he stayed his course. He envisioned a massive Washington, D.C. campaign that would flood the nation's capital with an army of its poor and unemployed. "White America must recognize that justice for black people cannot be changed without radical changes in the structure of our society—changes that would redistribute economic and political power and that would end poverty, racism, and war."<ref> Oates, 446.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Assassination=== | |

| + | King's plans for the [[Poor People's March]] were interrupted in the spring of 1968 by a trip that he made to [[Memphis, Tennessee]] to show support for a [[strike]] by that city's sanitation workers. The SCLC leader's arrival in Memphis on April 3 created a local sensation and attracted a bevy of news reporters and cameramen. That night, two thousand supporters and a large press and television corps turned out at Mason Temple to hear an address by the twentieth century's most peaceful warrior. King had been extremely reluctant to make an appearance, but he finally decided that he would do so for the sake of the people who so dearly loved him. The address that encapsulated and reaffirmed his life that night was destined to become known as his "I've Been To The Mountaintop" speech. By this time, to those who knew him, King had given the impression that his life may be near its end. The next day, April 4, 1968, at 6:01<small>P.M.</small>, as the SCLC leader stood on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel where he was lodging, the loud crack of a high-powered rifle was heard, and a bullet decimated the right side of King's face with such impact that it ferociously knocked him backward. | ||

| + | [[Image:Martin Luther King was shot here Small Web view.jpg|400px|thumb|The Lorraine Motel, where Rev. King was assassinated, now the site of the National Civil Rights Museum]] | ||

| + | [[Image:MLK tomb.JPG|thumb|400px|Martin Luther King's tomb, located on the grounds of the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site (King Center)]] | ||

| + | At 7:05<small>P.M.</small>, lying on an operating table at Saint Joseph's Hospital, Martin Luther King, Jr. was pronounced dead. News of the assassination sparked a nationwide wave of [[riot]]s in more than 110 cities, with the worst damage being wreaked in Washington, D.C. In total, 39 people were killed during the mayhem, and section after section of one blazing city after another looked like a war zone. Ironically, the most egregious outburst of [[looting]], [[theft]], [[arson]], and [[murder]] had been incited by the death of the man who had incessantly taken his stand for nonviolence and peace.<ref> Oates, 475-476.</ref> In honor of the fallen visionary, [[Lyndon Baines Johnson|President Johnson]] declared Sunday, April 7, a national day of mourning. Across the country, flags flew at half mast, and hordes of black and white Americans, together and in unison, marched, prayed, and sang freedom songs in tribute to King. After lying in state at the chapel of Spelman College, King's [[funeral]] was held on April 9 at Ebenezer Baptist Church, with Rev. Abernathy officiating. Finally, with 120 million Americans viewing by television, the special hearse bore the SCLC leader's body to South View Cemetery, where he was buried next to his grandparents. | ||

| − | + | Meanwhile, King's [[assassination]] had sparked one of the biggest manhunts in U.S. history. Two months after the SCLC leader's murder, escaped convict [[James Earl Ray]] was apprehended at [[London]]'s Heathrow Airport, while attempting to leave the [[United Kingdom]], using a false [[Canada|Canadian]] passport, under the name of "Ramon George Sneyd." Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King's assassination, to which he confessed on March 10, 1969. Three days later, he recanted this confession. Subsequently, Ray was sentenced to a 99-year prison term. Since then, there has been seemingly endless [[investigation]], re-investigation, hearing, re-hearing, and speculation regarding Ray's guilt or innocence, the murder weapon and the culpability or non-culpability of the U.S. Government in relation to King's death. Key players have died, confessions have been recanted and altered, and vast [[conspiracy]] has been alleged but never proven. Long believed by many in the [[African-American]] community is the assertion that King's murder was the outcome of an [[FBI]]-led conspiracy. | |

| − | + | In the eyes of many others, by the late 1990s, James Earl Ray had been exonerated, and former Memphis bar owner, [[Lloyd Jowers]], emerged as the obvious culprit. At the time of Ray's death, in April 1998, King's son, Dexter Scott King, had come to believe that Ray was not involved in the assassination plot. In 1999, [[Coretta Scott King]], along with the rest of King's family, won a wrongful death civil trial against Lloyd Jowers and "other unknown co-conspirators." Jowers claimed to have received $100,000 to arrange King's assassination. The jury of six whites and six blacks found Jowers guilty and also found that "governmental agencies were parties" to the assassination plot. William Pepper represented the King family in the trial.<ref>Bill Pepper, [https://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/WFPonMLK.pdf William F. Pepper on the MLK Conspiracy Trial], ''Rat Haus Reality Press'', April 7, 2002. Retrieved January 18, 2023.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In 2000, the Department of Justice completed its investigation into Jowers' claims, but did not find evidence to support the allegations about [[conspiracy]]. The investigation report recommends no further investigation unless some new reliable facts are presented.<ref>[https://www.justice.gov/crt/united-states-department-justice-investigation-allegations-regarding-assassination-dr-martin USDOJ Investigation of Recent Allegations Regarding the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, J"] ''United States Department of Justice'', June 2000. Retrieved January 18, 2023.</ref> | |

| − | The | + | Later, in April 2002, Rev. Ronald Denton Wilson of Keystone Heights, Florida, told ''The New York Times'' that his father, Henry Clay Wilson, and not James Earl Ray, was the assassin of Martin Luther King, Jr. Rev. Wilson contended that his father was the leader of a small group of conspirators; that racism had nothing to do with the murder; Henry Clay Wilson shot King because of the former's belief that the latter was connected with the [[Communist]] movement; and that James Earl Ray was set up to take the fall for the assassination. |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | ===Intellectual Excellence=== | ||

| + | As one of the most widely revered figures in American history, Martin Luther King, Jr. is lauded the world over for his intellectual prowess and for his accomplishments in the moral and socio-political arenas of human affairs. During his lifetime, he was essentially unmatched in his ability to articulate the crucial issues and concerns of humanity from a genuinely prophetic vantage point, using scriptural phraseology and imagery with an adeptness that other clergymen envied. The comprehensiveness of King's Judeo-Christian worldview was astounding, and his trenchant theological and philosophical analysis of the world and its problems customarily left his opponents speechless and at a loss to offer any counterproposal to his assessments. A highly competent intellectual as well as a bona fide revolutionary, he could artfully turn phrases and eloquently paint word pictures that inspired hope, confidence, and courageous commitment within the hearts and minds of his listeners. In this regard, he was a stellar example of what [[W.E.B. Du Bois]] referred to as the black race's Talented Tenth. King's ability to methodically think through and systematize his vast amount of learning and then call upon it to fuel the hearts and minds of millions is worthy of humanity's admiration. | ||

| − | + | ===Lifestyle of Nonviolence=== | |

| − | + | To this day, historians, politicians, sociologists, and religionists are fascinated by the fact that King's words and example actually inspired a generation to adopt the lifestyle of being viciously struck first, only to subsequently rise to victory over those who struck them, while praying for the forgiveness of their attackers. King succeeded in persuading his followers to embrace the idea that '''unearned suffering is redemptive'''—that one can recover one's lost position and/or overtake one's opposition through [[suffering]] that is unjustly inflicted but is accepted, digested, and overcome. By embracing this [[nonviolence|nonviolent]] tradition, King and his followers were consciously imitating the pattern established by [[Jesus]], and the civil-rights victories that were subsequently won loomed as proof that the Living [[God]] was with these protagonists of [[racial integration]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===World Wide Recognition=== | |

| + | During his lifetime, King received hundreds of honors and awards, including the [[Nobel Peace Prize]], and ''TIME'' magazine's "Man Of The Year." With his talents and his advanced degree, he could have earned millions of dollars, had he followed his heart's desire and focused on building his own career—especially after the success he wrought with the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Birmingham Campaign. | ||

| + | [[Image:Westminster Abbey C20th martyrs.jpg|thumb|400px|right|From the Gallery of twentieth century martyrs at [[Westminster Abbey]] (left to right) Grand Duchess [[Elizabeth Fyodorovna]] of Russia, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Archbishop [[Oscar Romero]], Pastor [[Dietrich Bonhoeffer]]]] | ||

| + | One example of King's honored reputation is the fact that a 2005 televised call-in poll identified him as the third greatest American, after [[Ronald Reagan]] and [[Abraham Lincoln]]. Even posthumous revelations of marital infidelity, and alleged academic [[plagiarism]] have not seriously damaged his public reputation, but have actually reinforced the image of a very human hero and leader. It is fair to state that King's movement faltered rather noticeably, during the latter days of his ministry, after the major legislative victories—the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act—had been won by 1965. But even the acrimonious strictures from some of the more militant voices of the [[Black Power]] Movement, and from even such prominent critics as Muslim leader [[Malcolm X]], have not significantly diminished King's stature. | ||

| − | + | On the international scene, King's legacy includes his influence on the luminaries of the Black Consciousness Movement and particularly on the leaders of the Civil Rights Movements in South Africa. In that country, King's work was cited by and served as an inspiration for another black Nobel Peace Prize winner and crusader for racial justice, [[Albert Lutuli]]. | |

| − | + | ===Memorials=== | |

| + | King's legacy and memory live on in numerous ways. In Atlanta, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change was established in 1968 by his widow, Coretta, who served as its president until her death. Coretta made great efforts to follow in her husband's footsteps and to remain on the front line of social and moral issues. King's son, Dexter Scott King, currently serves as the Center's president and CEO. | ||

| − | + | In 1980, King's boyhood home in Atlanta and several other nearby structures were designated as the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site. At the [[White House]] Rose Garden, on November 2, 1983, President Reagan signed a bill creating a [[federal holiday]] to honor King. It was observed for the first time on January 20, 1986. Martin Luther King Day is observed on the third Monday of January each year, around the time of King's birthday. On January 17, 2000, for the first time, Martin Luther King Day was officially observed by name in all 50 American states.<ref> Michael Brindley, https://www.nhpr.org/nh-news/2013-08-27/n-h-s-martin-luther-king-jr-day-didnt-happen-without-a-fight#stream/0 N.H.'s Martin Luther King Jr. Day Didn't Happen Without A Fight] ''NHPR'', August 27, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2023.</ref> This is one of three national holidays dedicated to an individual American, and it is the only one dedicated to an African-American. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In city after city, across the United States, scores of streets, highways, and boulevards are either named or renamed after Martin Luther King, Jr. King County, Washington rededicated its name in honor of King in 1986. The city government center in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania is the only city hall in the United States to be named in honor of King. | |

| − | + | In 1998, Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity was authorized by the United States Congress to establish a foundation to manage the related fundraising for and the design of a Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial. King was a prominent member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established for American blacks. King is the first African-American to be honored with his own memorial in the National Mall area and the second non-president to be commemorated in such a way. Covering four acres, the memorial opened to the public on August 22, 2011, after more than two decades of planning, fund-raising and construction.<ref>Sabrina Tavernise, [https://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/23/us/23mlk.html?_r=1&smid=fb-nytimes&WT.mc_id=US-SM-E-FB-SM-LIN-ADF-082311-NYT-NA&WT.mc_ev=click A Dream Fulfilled, Martin Luther King Memorial Opens] ''New York Times'', August 22, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2023.</ref><ref name=Cooper1>Rachel Cooper, [https://www.tripsavvy.com/martin-luther-king-jr-memorial-in-washington-dc-1039274 Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial in Washington, DC: Building a Memorial Honoring Martin Luther King, Jr.] ''Trip Savvy'', December 13, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2023.</ref> The [[monument|monumental]] memorial is located at the northwest corner of the [[Tidal Basin]] near the [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial]], on a sightline linking the [[Lincoln Memorial]] to the northwest and the [[Jefferson Memorial]] to the southeast. The official address of the monument, 1964 Independence Avenue, S.W., commemorates the year that the [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]] became law. The King Memorial is administered by the [[National Park Service]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | King is | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Authorship Issues== | ==Authorship Issues== | ||

| − | + | Beginning in the 1980s, questions have been raised regarding the authorship of King's dissertation, other papers, and his speeches. Concerns about his doctoral dissertation at [[Boston University]] led to a formal inquiry by university officials, which concluded that approximately a third of it had been [[plagiarism|plagiarized]] from a paper written by an earlier graduate student, but it was decided not to revoke his degree, as the paper still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship." Such uncredited "textual appropriation," as King scholar Clayborne Carson has labeled it, was apparently a habit of King's, begun earlier in his academic career. It is also a feature of many of his speeches, which borrowed heavily from those of other preachers and white radio evangelists. While some have criticized King for [[plagiarism]], Keith Miller has argued that the practice falls within the tradition of African-American folk preaching, and should not necessarily be labeled plagiarism. However, as Theodore Pappas points out in his book ''Plagiarism and the Culture War,'' King in fact took a class on scholarly standards and plagiarism at Boston University <ref>Theodore Pappas, ''Plagiarism and the Culture War'' (Tampa, FL: Hallberg Pub, 1998, ISBN 0873190459).</ref> Far from it being true that other people wrote his speeches, it is evident from his papers, now available for research, that he drafted and redrafted these by his own distinct and very legible handwriting. However, almost all of what is perhaps his most famous speech, "I have a dream" was delivered spontaneously.<ref> [https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/about-papers-project Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project] ''The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University''. Retrieved January 18, 2023.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Quotations== | |

| + | *Human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of men willing to be coworkers with God; and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation.<ref name=Letter/> | ||

| − | + | *The belief that God will do everything for man is as untenable as the belief that man can do everything for himself. It, too, is based on a lack of faith. We must learn that to expect God to do everything while we do nothing is not faith but superstition.<ref> Martin Luther King, Jr., ''Strength to Love'' (NY: Walker & Co, 1984, ISBN 0802724728), 133.</ref> | |

| − | * | + | *A religion true to its nature must also be concerned about man's social conditions. Religion deals with both Earth and Heaven, both time and eternity. Religion operates not only on the vertical plane, but also on the horizontal. It seeks not only to integrate men with God, but to integrate men with men and each man with himself. This means, at bottom, that the Christian gospel is a two-way road. On the one hand, it seeks to change the souls of men and thereby unite them with God; on the other hand, it seeks to change the environmental conditions of men so that the soul will have a chance after it is changed. Any religion that professes to be concerned with the souls of men and is not concerned with the slums that damn them, the economic conditions that strangle them, and the social conditions that cripple them is a dry-as-dust religion. Such a religion is the kind the Marxists like to see—an opiate of the people.<ref>Martin Luther King, Jr., ''Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story'' (NY: Harper, 1987< ISBN 0062504908), 36.</ref> |

| − | + | ==Publications== | |

| − | + | *1958 ''Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story.'' NY: Harper, reprinted 1987. ISBN 0062504908 | |

| − | == | + | *1959 ''The Measure of a Man.'' Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, reprint 2001. ISBN 0800634497 |

| − | *''Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story'' | + | *1963 ''Strength to Love.'' NY: Walker & Co, reprint 1984. ISBN 0802724728 |

| − | *''The Measure of a Man'' | + | *1964 ''Why We Can't Wait.'' NY: New American Library, reprint 2000. ISBN 0451527534 |

| − | *''Strength to Love'' | + | *1967 ''Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?'' Boston, MA: Beacon Press. ISBN 0807005711 |

| − | *''Why We Can't Wait'' | + | *1968 ''The Trumpet of Conscience: The Summing-Up of His Creed, and His Final Testament.'' NY: HarperCollins, 1989. ISBN 0062504924 |

| − | *''Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?'' | + | *1986 ''A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr,'' edited by James Melvin Washington. NY: Harper & Row, 1986. ISBN 0062509314 |

| − | *''The Trumpet of Conscience'' | + | *1998 ''The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.'' by Martin Luther King, Jr. and Clayborne Carson, NY: Intellectual Properties Management in association with Warner Books, 1998. ISBN 0446524123 |

| − | *''A Testament of Hope : The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr | ||

| − | *''The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.'' by Martin Luther King Jr. and Clayborne Carson | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 408: | Line 174: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | * Abernathy, Ralph. ''And the Walls Came Tumbling Down: An Autobiography.'' NY: Harper & Row, 1989. ISBN 0060161922 |

| − | *Beito, David and | + | * Ayton, Mel, ''A Racial Crime: James Earl Ray And The Murder Of Martin Luther King Jr.'' Las Vegas, NV: Archebooks Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1595070753 |

| − | * Branch, Taylor. ''At Canaan's Edge: America In the King Years, 1965-1968.'' | + | * Beito, David and Linda Roystereito. "T.R.M. Howard: Pragmatism over Strict Integrationist Ideology in the Mississippi Delta, 1942-1954." in Glenn Feldman, ed., ''Before Brown: Civil Rights and White Backlash in the Modern South.'' Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004, 68-95. ISBN 0817351345. |

| − | *''Parting the waters : America in the King years, 1954-1963.'' | + | * Branch, Taylor. ''At Canaan's Edge: America In the King Years, 1965-1968.'' NY: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 068485712X |

| − | *''Pillar of fire : America in the King years, 1963-1965.'': Simon & Schuster, 1998. ISBN | + | * Branch, Taylor. ''Parting the waters: America in the King years, 1954-1963.'' NY: Simon & Schuster, 1988. ISBN 0671460978 |

| − | * Chernus, Ira. ''American Nonviolence: The History of an Idea'', | + | * Branch, Taylor. ''Pillar of fire : America in the King years, 1963-1965.'' NY: Simon & Schuster, 1998. ISBN 0684808196 |

| − | * Garrow, David J. ''The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr.'' | + | * Chernus, Ira. ''American Nonviolence: The History of an Idea.'' Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1570755477 |

| − | * Kirk, John A., ''Martin Luther King, Jr.'' London: Pearson Longman, 2005. ISBN | + | * Downing, Frederick L. ''To See the Promised Land: The Faith Pilgrimage of Martin Luther King, Jr.'' Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0865542075 |

| − | * | + | * Garrow, David J. ''The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr.'' NY: Penguin Books, 1981. ISBN 0140064869 |

| + | * Heffner, Richard D. ''A Documentary History of the United States,'' Third ed., NY: Signet, 1991. ISBN 0451207483 | ||

| + | * Kirk, John A., ''Martin Luther King, Jr.'' London: Pearson Longman, 2005. ISBN 0582414318 | ||

| + | * Oates, Stephen B. ''Let the Trumpet Sound: Life of Martin Luther King, Jr.'' NY: HarperPerennial, 1982 (reprinted 1994) ISBN 006092473X | ||

| + | * Pappas, Theodore. ''Plagiarism and the Culture War.'' Tampa, FL: Hallberg Pub, 1998. ISBN 0873190459 | ||

| + | * Washington, James Melvin. ''Testament of Hope: the essential writings and speeches of Martin Luther King, JR.'' San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991. ISBN 0060646918 | ||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 7, 2022. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | * [http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/ The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project] ''Stanford University''. MLK Research and Education Institute. | |

| − | * [http:// | ||

* [http://www.thekingcenter.org/ The King Center] | * [http://www.thekingcenter.org/ The King Center] | ||

* [http://www.civilrightsmuseum.org/ National Civil Rights Museum] | * [http://www.civilrightsmuseum.org/ National Civil Rights Museum] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/mlk/ The Seattle Times: Martin Luther King Jr.] | * [http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/mlk/ The Seattle Times: Martin Luther King Jr.] | ||

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/biographical/ Winner of the 1964 Nobel Prize in Peace] |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.thoughtco.com/men-who-inspired-martin-luther-king-jr-4019032 5 Men Who Inspired Martin Luther King, Jr. to be a Leader] |

| − | * [http://www.writespirit.net/inspirational_talks/political/martin_luther_king_talks/ Speeches of Martin Luther King] | + | * [http://www.writespirit.net/inspirational_talks/political/martin_luther_king_talks/ Speeches of Martin Luther King] ''Write Spirit''. full text "Beyond Vietnam," New York, N.Y., April 4, 1967. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.martin-luther-king-zentrum.de The Martin Luther King Center (German)] | * [http://www.martin-luther-king-zentrum.de The Martin Luther King Center (German)] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.ep.tc/mlk/ 1956 Comic Book: "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story"] | * [http://www.ep.tc/mlk/ 1956 Comic Book: "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story"] | ||

| − | * | + | * [http://www.nps.gov/mlkm/index.htm Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial] National Park Service |

| − | + | * ''Internet Archive'': [http://www.archive.org/movies/movies-details-db.php?collection=open_mind&collectionid=openmind_ep727 The New Negro], King interviewed by J. Waites Waring. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

* [http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm Transcript, Audio, Video of King's "I Have A Dream" speech] | * [http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm Transcript, Audio, Video of King's "I Have A Dream" speech] | ||

* [http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkivebeentothemountaintop.htm Transcript and Audio of King's "I've Been To The Mountaintop" speech] | * [http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkivebeentothemountaintop.htm Transcript and Audio of King's "I've Been To The Mountaintop" speech] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{Template:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates 1951-1975}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Nobel Peace Prize Winners]] | |

| − | + | [[category:biography]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category:Nobel Peace Prize | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|84106061}} | {{Credit|84106061}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:52, 18 January 2023

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929–April 4, 1968) was America's foremost civil rights leader and is deemed by many as the greatest American leader of the twentieth century. His leadership was fundamental to ending legal segregation in the United States and empowering the African-American community. A moral leader foremost, he espoused nonviolent resistance as the means to bring about political change, emphasizing that spiritual principles guided by love can triumph over politics driven by hate and fear. He was a superb orator, best known for his "I Have a Dream" speech given at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. King became the youngest person to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

At age 39, he was killed by an assassin's bullet in 1968. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s impact and legacy was not limited to the U.S., but was worldwide, including influencing the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. Honored on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, the third Monday in January close to his birthday, King is only one of three Americans to have a national holiday, and the only African-American.

Introduction

Martin Luther King, Jr. combined the qualities that propelled him to world-figure-hero status during the course of his life. No other scholar-activist, except possibly Mahatma Gandhi, did as fine a job of descending from the lofty level of the ivory tower and walking among the masses, meeting them at their level, giving voice to their yearnings, and exemplifying the common touch. Comfortable in his own skin and confident in the righteousness of his cause, King still grappled daily with the doubts, struggles, and temptations that inevitably burden all leaders. Stephen B. Oates tells us that:

Like everybody, King had imperfections: he had hurts and insecurities, conflicts and contradictions, guilts and frailties, a good deal of anger, and he made mistakes. …his achievements… were astounding for a man who was cut down at the age of only 39 and who labored against staggering odds—not only the bastion of segregation that was the American South of his day, but the monstrously complex racial barriers of the urban North, a hateful FBI crusade against him, a lot of jealousy on the part of rival civil-rights leaders and organizations, and finally the Vietnam War and a vengeful Lyndon Johnson. King was all things to the American Negro movement—advocate, orator, field general, historian, fund raiser, and symbol. Though he longed to be a teacher and scholar on the university level, he became instead a master of direct-action protest, using it in imaginative and unprecedented ways to stimulate powerful federal legislation that radically altered Southern race relations.[1]

Despite his flaws, King maintained an attitude of public-minded, self-sacrificial service, which was the hallmark of both his impressively enlightened Christian faith and his lifestyle of prayer, perseverance, and contemplation.

Before the end of his life, he had (1) become the third black and the youngest person to ever receive the Nobel Peace Prize; (2) established himself as the chief architect and premiere spokesperson for the Civil Rights Movement of 1955-1968—an authentically religious revival, the socio-political impact of which was unprecedented in human history; (3) been jailed for a total of twenty-nine times, in the name of freedom and justice; (4) witnessed, first hand, the death of the wickedly racist Jim-Crow system of legal segregation in the South; and (5) led the Civil Rights struggle on its march toward inspiring the United States of America to earnestly practice the truths found in the Bible, which stands as the cornerstone of its republican form of government. He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Jimmy Carter, in 1977, and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2004. In 1986, during the administration of President Ronald Reagan, Martin Luther King Day was established in his honor. King's most influential and well-known public address is his world-renowned "I Have A Dream" speech, delivered at the Lincoln Memorial, on August 28, 1963.

Through intense study and masterfully systematic thought, King successfully merged his intimate knowledge of the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Mayflower Compact, and other documents, with his strikingly insightful, biblical worldview. As a result, he ultimately forged within himself an undying love for America and a passion for its destiny. That passion fueled his vision and instilled his being with a flaming religious commitment. It was this committed life that made it possible for him to become both a sterling example of sacrificial leadership and a providential instrument of the most noble Judeo-Christian ideals. And it was that model of leadership that fueled the Civil Rights Movement in its nearly successful effort at inciting a Christian Revolution within the borders of the United States.

Biography

Birth, early life, and education

Martin Luther King, Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, the second child and first son of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr., and Mrs. Alberta Williams King. Reverend King—the boy's father—was pastor of black Atlanta's historical, influential, and prestigious Ebenezer Baptist Church. As such, the Rev. King was likewise a pillar in Atlanta's black middle class. He ruled his household with a fierceness not unlike that of an Old Testament patriarch, and he provided a lifestyle in which his children were disciplined, protected, and very well provided for. By the Reverend King's decree, his son (Martin Luther King, Jr.), during the course of his youth, went by the name "M.L." A strong and healthy newborn, M.L. had been preceded in birth by his sister, Willie Christine, and was followed by his brother, Alfred Daniel, or A.D. Within the context of his rearing, and because he was his father's son, the church was M.L.'s second home. It functioned as the hub around which the wheel of King family life rotated. And the sanctuary was located only three blocks away from the big house on Auburn Avenue. Having been slipped, by his parents, into grade school a year early, and having been bright and gifted enough to skip a number of grades along the way, M.L. entered Booker T. Washington High School in 1942, at the age of 13. Two years later, as an exceptional high school junior, he passed Morehouse College's entrance exam, graduated from Booker T. Washington after the eleventh grade, and, at the age of 15, enrolled in Morehouse. There, he was mentored by the school's president, civil rights veteran Benjamin Mays. King graduated from Morehouse in 1948, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Sociology. He subsequently enrolled at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was elected student-body president, and from where he later graduated as class valedictorian, with a Bachelor of Divinity degree, in 1951.[2]

In 1955, he received a Doctor of Philosophy in Systematic Theology from Boston University. Thus, from the age of 15 until 26, King embarked upon a pilgrimage of intellectual discovery. Through it, he systematized a religious and social worldview, characterized by unusually striking insights and by an unshakable adherence to the power of nonviolence and redemption through unearned suffering.

Marriage and family life

Following a whirlwind, 16-month courtship, Martin Luther King, Jr., married Coretta Scott, on June 18, 1953. King's father performed the wedding ceremony at the residence of Scott's parents in Marion, Alabama.

Martin and Coretta Scott King were the parents of four children:

- Yolanda Denise (b. November 17, 1955, Montgomery, Alabama; d. May 15, 2007)

- Martin Luther III (b. October 23, 1957, Montgomery, Alabama)

- Dexter Scott (b. January 30, 1961, Atlanta, Georgia)

- Bernice Albertine (b. March 28, 1963, Atlanta, Georgia)

All four children followed in their father's footsteps as civil rights activists, although their opinions differ on a number of controversial issues. Coretta Scott King passed away on January 30, 2006.

Career and civil rights activism

The best way to understand the impact of King's 13-year crusade for freedom and justice is to divide his career into two periods—before the Selma, Alabama campaign and after it. The first period ignited with the Montgomery Bus Boycott of December 1955 and closed with the successful voting-rights march from Selma to Montgomery, on March 25, 1965. The second period commenced with the January 1966 Chicago campaign for jobs and slum elimination and ended with the assassination of King on April 4, 1968, in Memphis. During the first period, King's belief in divine justice and his vision of a new Christian social order fueled his sublime oratory and his equally sublime courage. This resulted in a shared commitment to the concept of "noncooperation with evil," that swept the ranks of Civil Rights Movement devotees. Through nonviolent, passive resistance, they protested the social evils and injustices of segregation and refused to obey and/or comply with unjust and immoral Jim Crow laws. The subsequent beatings, jailings, abuses, and violence that were heaped upon these protesters ultimately became the price they paid for unprecedented victories.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott