Strike

Strikes are suspensions of work against an employer, factory, industry, and so forth, performed by workers and maintained until some demand is met by the entity against which they are striking. Most strikes are undertaken by labor unions during collective bargaining, in attempts to improve workplace conditions, increase wages, or obtain better contracts between the union and the company. Strikes are sometimes used to put pressure on governments to change policies. Occasionally, strikes destabilize the rule of a particular political party.

Strikes are generally initiated out of good intentions on the part of the workers, a way of pressuring employers or the government to treat them more fairly for the benefit of all. However, self-centered thinking can cloud the issue. When unions do not take into account the needs of society as a whole but rather seek to obtain benefit only for themselves the results may be harmful to all. In such cases, government must intervene for the good of all its citizens. On the other hand, when government abuses its power, a general strike is an effective, non-violent way of forcing those in power to rethink their position.

History of strikes

The strike tactic has a very long history. Towards the end of the twentieth dynasty, under Pharaoh Ramses III in ancient Egypt in the twelfth century B.C.E., the workers of the royal necropolis organized the first known strike or workers' uprising in history. Much later, in 1768, in support of demonstrations in London, sailors "struck," or removed the top-gallant sails of merchant ships at port, thus crippling the ships.

Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labor became important in factories and mines, and workers were often exploited by their employers.

For example, during the economic panic of 1893, the Pullman Palace Car Company cut wages 28 percent as demands for their train cars plummeted and the company's revenue dropped. When Pullman refused to negotiate, 4,000 Pullman Palace Car Company workers reacted by going on a wildcat strike in Illinois on May 11, 1894, bringing traffic west of Chicago to a halt. The strike was broken up by United States Marshals and some 2,000 United States Army troops, commanded by Nelson Miles, sent in by President Grover Cleveland on the premise that the strike interfered with the delivery of U.S. Mail, ignored a federal injunction, and represented a threat to public safety.

In most countries, strikes were made illegal, as factory owners had far more political power than workers. However, most western countries partially legalized striking in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries.

Categories of strikes

Strikes occur for a number of reasons, the most common being economic issues (wages and hours of work) and workplace conditions. United States labor law draws a distinction, in the case of private sector employers covered by the National Labor Relations Act, between "economic" and "unfair labor practice" strikes. An employer may not fire, but may permanently replace, workers who engage in a strike over economic issues. On the other hand, employers charged with committing unfair labor practices (ULPs) may not replace employees who strike over ULPs, and must fire any strikebreakers they have hired as replacements in order to reinstate the striking workers.

Most strikes are undertaken by labor unions during collective bargaining. The object of collective bargaining is to obtain a contract (an agreement between the union and the company,) and the contract may include a no-strike clause which prevents strikes, or penalizes the union and/or the workers if they walk out while the contract is in force. The strike is typically reserved as a threat of last resort during negotiations between the company and the union, which may occur just before, or immediately after, the contract expires.

Strikes may be specific to a particular workplace, employer, or unit within a workplace, or they may encompass an entire industry, or every worker within a city or nation. Strikes that involve all workers, or a number of large and important groups of workers, in a particular community or region are known as general strikes. Under some circumstances, strikes may take place in order to put pressure on the State or other authorities. A notable example is the GdaĹsk Shipyard strike led by Lech WaĹÄsa. This strike was significant in the struggle for political change in Poland, and was an important mobilized effort that contributed to the fall of governments in communist East Europe.

A strike may consist of workers refusing to attend work or picketing outside the workplace to prevent or dissuade people from working in their place or conducting business with their employer. Less frequently, workers may occupy the workplace, but refuse either to do their jobs or to leave. This is known as a "sit-down strike."

Wildcat strikes

Generally, strikes are rare: According to the News Media Guild, 98 percent of union contracts in the United States are settled each year without a strike. Occasionally, workers decide to strike without the sanction of a labor union, either because the union refuses to endorse such a tactic, or because the workers concerned are not unionized. Such strikes are often described as "unofficial." Strikes without formal union authorization are also known as "wildcat strikes." In many countries, wildcat strikes do not enjoy the same legal protections as recognized union strikes, and may result in penalties for the union members who participate or their union. The same often applies in the case of strikes conducted without an official ballot of the union membership, as is required in some countries such as the United Kingdom.

Italian strike

Another unconventional tactic is work-to-rule (also known as an "Italian strike," in Italian Sciopero bianco), in which workers perform their tasks exactly as they are required to but no better. For example, workers might follow all safety regulations in such a way that it impedes their productivity or they might refuse to work overtime. Such strikes may in some cases be a form of "partial strike" or "slowdown;" while Italian law allows that (no one can be sanctioned for following the safety and/or security rules) such form of strike is "unprotected" in some circumstances under United States labor law, meaning that while the tactic itself is not unlawful, the employer may fire the employees who engage in it.

Green ban

During the development boom of the 1970s, in Australia, the "Green ban" was developed by certain more socially conscious unions. This is a form of strike action taken by a trade union or other organized labor group for environmentalist or conservationist purposes. This developed from the "black ban," strike action taken against a particular job or employer in order to protect the economic interests of the strikers.

Sympathy strike

A sympathy strike is, in a way, a small scale version of a general strike in which one group of workers refuses to cross a picket line established by another as a means of supporting the striking workers. Sympathy strikes, once the norm in the construction industry in the United States, have been made much more difficult to conduct due to decisions of the National Labor Relations Board permitting employers to establish separate or "reserved" gates for particular trades, making it an unlawful secondary boycott for a union to establish a picket line at any gate other than the one reserved for the employer it is picketing. Sympathy strikes may be undertaken by a union as an organization or by individual union members choosing not to cross a picket line. In Britain, sympathy strikes were banned by the Thatcher government in 1980.

Others

A "jurisdictional strike" in United States labor law refers to a concerted refusal to work undertaken by a union to assert its membersâ right to particular job assignments and to protest the assignment of disputed work to members of another union or to unorganized workers.

Employers of labor can also go on strike; either through a lock-out of workers (blocking workers from working normally, resulting in loss of wages) or through an investment strike (refusing to commit funds to maintaining or expanding production).

A "student strike" has the students (sometimes supported by faculty) not attending schools. Unlike other strikes, the target of the protest (the educational institution or the government) does not suffer a direct economical loss but one of public image.

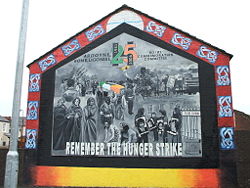

A Hunger strike is the voluntary refusal to eat. Hunger strikes are often used in prisons as a form of political protest. Like student strikes, a hunger strike aims to worsen the public image of the target.

A "sickout," also known as the "Blue flu," is a quasi-legal way for police, firefighters, and air traffic controllers to strike: They call in sick en masse.

A "Japanese strike," on the contrary, has the workers maximizing their output. They are nominally working as usual, but the surplus can break the planning, especially in just-in-time systems.

Legal prohibitions on strikes

The Railway Labor Act bans strikes by United States airline and railroad employees except in narrowly defined circumstances. The National Labor Relations Act generally permits strikes, but provides for a mechanism to enjoin strikes in industries in which a strike would create a national emergency. The federal government invoked these statutory provisions to obtain an injunction against a slowdown by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union in 2002.

Some jurisdictions prohibit all strikes by public employees (under such laws as the "Taylor Law" in New York). Other jurisdictions limit strikes only by certain categories of workers, particularly those regarded as critical to society: Police and firefighters are among the groups commonly barred from striking in these jurisdictions. Some states, such as Iowa or Florida, do not allow teachers in public schools to strike. Workers have sometimes circumvented these restrictions by falsely claiming inability to work due to illnessâthis is sometimes called a "sickout" or "blue flu." The term "red flu" has sometimes been used to describe this action when undertaken by firefighters.

It is also illegal for an employee of the United States Federal Government to strike. Prospective federal employees must sign standard form 61, an affidavit not to strike. President Ronald Reagan terminated air traffic controllers after their refusal to return to work from an illegal strike in 1981.

In Communist regimes, such as the former USSR or the People's Republic of China, striking is illegal and viewed as counter-revolutionary. Since the government in such systems claims to represent the working class, it has been argued that unions and strikes were not necessary.

Most totalitarian systems of the left and right also ban strikes. In some democratic countries, such as Mexico, strikes are legal but subject to close regulation by the state.

"Scabs"

The term "scab" is a highly derogatory term most frequently used to refer to people who continue to work when trade unionists go on strike action. This is also known as "crossing the picket line" and often results in their being shunned or even assaulted.

The terms "strike-breaker," "blackleg," and "scab labor" are also used. Trade unionists also use the epithet "scab" to refer to workers who are willing to accept terms that union workers have rejected and interfere with the strike action. Some say that the word comes from the idea that the "scabs" are covering a wound. However, "scab" was an old-fashioned English insult. An older word is "blackleg" and this is found in the old folk song, "Blackleg Miner," which has been sung by many groups.

The classic example from United Kingdom industrial history is that of the miners from Nottinghamshire, who during the 1984-1985 miners' strike did not support strike action by fellow mineworkers in other parts of the country. Those who supported the strike claimed that this was because they enjoyed more favorable mining conditions and, thus, better wages. However, the Nottinghamshire miners argued that they did not participate because the law required a ballot for a national strike and their area vote had seen around 75 percent vote against a strike.

During "economic" strikes in the U.S., scabs may be hired as permanent replacements.

"Union scabbing"

The concept of "union scabbing" refers to any circumstance in which union workers, who normally might be expected to honor picket lines established by fellow working folk during a strike, are inclined or compelled to cross those picket lines or, in some manner, otherwise engage in workplace activity which may prove injurious to the strike.

Unionized workers are sometimes required to cross the picket lines established by other unions due to their organizations having signed contracts which include no-strike clauses. The no-strike clause typically requires that members of the union not conduct any strike action for the duration of the contract. Members who honor the picket line in spite of the strike frequently face discipline, for their action may be viewed as a violation of provisions of the contract. Therefore, any union conducting a strike action typically seeks to include a provision of amnesty for all who honored the picket line in the agreement that settles the strike.

No strike clauses may also prevent unionized workers from engaging in solidarity actions for other workers even when no picket line is crossed. For example, striking workers in manufacturing or mining produce a product which must be transported. In a situation where the factory or mine owners have replaced the strikers, unionized transport workers may feel inclined to refuse to haul any product that is produced by strikebreakers, yet their own contract obligates them to do so.

Historically the practice of union scabbing has been a contentious issue in the union movement, and a point of contention between adherents of different union philosophies. For example, supporters of industrial unions, which have sought to organize entire workplaces without regard to individual skills, have criticized craft unions for organizing workplaces into separate unions according to skill, a circumstance that makes union scabbing more common. Union scabbing is not, however, unique to craft unions.

Methods used by employers to deal with strikes

Most strikes called by unions are somewhat predictable; they typically occur after the contract has expired. However, not all strikes are called by union organizationsâsome strikes have been called in an effort to pressure employers to recognize unions. Other strikes may be spontaneous actions by working people.

Whatever the cause of the strike, employers are generally motivated to take measures to prevent them, mitigate the impact, or to undermine strikes when they do occur.

Strike preparation

Companies which produce products for sale will frequently increase inventories prior to a strike. Salaried employees may be called upon to take the place of strikers, which may entail advance training. If the company has multiple locations, personnel may be redeployed to meet the needs of reduced staff.

Strike breaking

Some companies negotiate with the union during a strike; other companies may see a strike as an opportunity to eliminate the union. This is sometimes accomplished by the importation of replacement workers, or strike breakers. Historically, strike breaking has often coincided with union busting.

Union busting

One method of inhibiting a strike is elimination of the union that may launch it, which is sometimes accomplished through union busting. Union busting campaigns may be orchestrated by labor relations consultants, and may utilize the services of agencies that engage in intelligence gathering, or that provide asset protection services. Similar services may be engaged during attempts to defeat organizing drives.

Lockout

Another counter to a strike is a lockout, the form of work stoppage in which an employer refuses to allow employees to work. Two of the three employers involved in the Caravan park grocery workers strike of 2003-2004 locked out their employees in response to a strike against the third member of the employer bargaining group. Lockouts are, with certain exceptions, lawful under United States labor law.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Nordlund, Willis. 1998. Silent Skies: The Air Traffic Controllers' Strike. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0275961885

- Silver, Beverly. 2003. Forces of Labor: Workers' Movements and Globalization Since 1870. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521520770

- Smith, Stephanie. 2006. Household Words: Bloomers, Sucker, Bombshell, Scab, Nigger, Cyber. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816645531

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.