Boycott

To boycott is to abstain from using, buying, or dealing with a person or organization as an expression of protest or as a means of economic coercion in order to achieve justice. The boycott serves as a nonviolent tactic to further a cause, and can take on symbolic significance while effecting change. Boycotts were used successfully on many occasions in the twentieth century, furthering the cause of human rights around the world.

Origin of the term

The word boycott entered the English language during the Irish "Land War" and is derived from the name of Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott, the estate agent of an absentee landlord (the Earl Erne) in County Mayo, Ireland.

Boycott became subject to social ostracism organized by the Irish Land League in 1880. In September that year, protesting tenants demanded from Boycott a substantial reduction in their rents. He not only refused, but also ejected them from the land. The Irish Land League proposed that, rather than resorting to violence, everyone in the locality should refuse to deal with him. Despite the short-term economic hardship to those undertaking this action, Boycott soon found himself isolatedâhis workers stopped work in the fields, stables, and house. Local businessmen stopped trading with him, and the local postman refused to deliver him his mail.

The concerted action taken against Boycott rendered him unable to hire anyone to harvest the crops in his charge. Eventually 50 Orangemen from County Cavan and County Monaghan volunteered to complete the harvesting. One thousand policemen and soldiers escorted them to and from Claremorris, despite the fact that Boycott's complete social ostracism meant that he actually faced no danger of being harmed. Moreover, this protection ended up costing far more than the harvest's value. After the harvest, the "boycott" was successfully continued. Within weeks Boycott's name was everywhere.

The Times of London first used it on November 20, 1880 as a term of organized isolation: "The people of New Pallas have resolved to 'boycott' them and refused to supply them with food or drink." According to an account in the book The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland by Michael Davitt, Fr. John O' Malley from County Mayo coined the term to "signify ostracism applied to a landlord or agent like Boycott." The Daily News wrote on December 13, 1880: âAlready the stoutest-hearted are yielding on every side to the dread of being 'Boycotted'.â By January of the following year, reporters began using the word figuratively: "Dame Nature arose....She 'Boycotted' London from Kew to Mile End" (The Spectator, January 22, 1881).

On December 1, 1880 Captain Boycott left his post and withdrew to England with his family.

Applications and uses

The practice of boycotting dates back to at least 1830, when the National Negro Convention encouraged a boycott of slave-produced goods. A boycott is normally considered a one-time affair designed to correct an outstanding single wrong. When extended for a long period of time or as part of an overall program of awareness-raising or reform to laws or regimes, a boycott is part of "moral purchasing," or "ethical purchasing," and those economic or political terms are to be preferred.

Most organized consumer boycotts are focused on long-term change of buying habits and, therefore, fit into part of a larger political program with many techniques that require a longer structural commitment (e.g. reform to commodity markets, or government commitment to moral purchasing such as the longstanding embargo against South African businesses by the United Nations to protest apartheid). Such examples stretch the meaning of "boycott."

While a "primary boycott" involves refusal by employees to purchase goods or services of their employer, a "secondary boycott" is an attempt to convince others (third party) to refuse to purchase from the employer.

Significant boycotts of the twentieth century

- the Indian boycott of British goods organized by M. K. Gandhi

- multiple boycotts by African Americans during the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, including the Montgomery Bus Boycott

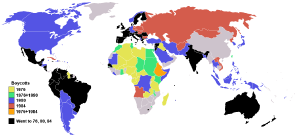

- the Olympic boycotts

- the United Farm Workers union's grape and lettuce boycotts

- the Arab League boycott of Israel and companies trading with Israel

- the Arab countries' crude oil embargo against the West in 1973

- the Nestlé boycott

- the United Nations boycott of Iraq.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a political, social, and economic protest campaign started in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama intended to oppose the city's policy of racial segregation on its public transit system. The ensuing struggle lasted from December 5, 1955 to December 21, 1956, and led to a United States Supreme Court decision that declared the Alabama and Montgomery laws requiring segregated buses unconstitutional.

Rosa Parks, a seamstress by profession, had been formally educated on civil rights and had a history of activism prior to the boycott. Shortly before her arrest in December 1955, she had completed a course in race relations at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Parks also served as secretary for the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP had planned the boycott, which functioned as a test case in challenging segregation on public buses, before Parks' arrest. Community leaders had been waiting for the right person to be arrested, a person who would anger the black community into action, who would agree to test the segregation laws in court, and who, most importantly, was "above reproach." When fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin, a straight-A student, was arrested early in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat, E.D. Nixon of the NAACP thought he had found the perfect person, but he soon found out Colvin was pregnant and unmarried. Nixon later explained, "I had to be sure that I had somebody I could win with." Rosa Parks fit this profile perfectly. [1] She was arrested on Thursday, December 1, 1955 for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger. When found guilty on Monday, December 5, 1955, she was fined $10 plus a court cost of $4, but she appealed. Rosa Parks also helped and supported the ensuing Montgomery Bus Boycott and is now considered one of the pioneering women of the Civil Rights Movement.

On Friday, December 2, 1955, Jo Ann Robinson, president of the Women's Political Council, received a call from Fred Gray, one of the city's two black lawyers, informing her of Parks' arrest. That entire night Robinson worked tirelessly, mimeographing over 35,000 handbills that read:

Another Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down. It is the second time since the Claudette Colvin case that a Negro woman has been arrested for the same thing. This has to be stopped. Negroes have rights, too, for if Negroes did not ride the buses, they could not operate. Three-fourths of the riders are Negroes, yet we are arrested, or have to stand over empty seats. If we do not do something to stop these arrests, they will continue. The next time it may be you, or your daughter, or mother. This woman's case will come up on Monday. We are, therefore, asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial. Don't ride the buses to work, to town, to school, or anywhere on Monday. You can afford to stay out of school for one day if you have no other way to go except by bus. You can also afford to stay out of town for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don't ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off all buses Monday.[2]

The next morning, local activists organized at a church meeting with the new minister in the city, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. They proposed and passed a citywide boycott of public transit as a protest against bus segregation.

The boycott proved extremely effective, with enough riders lost to the city transit system to cause serious economic distress. King later wrote, "A miracle had taken place." Instead of riding buses, boycotters organized a system of carpools, with car owners volunteering their vehicles or themselves driving people to various destinations. Some white housewives also drove their black domestic servants to work, although it is unclear to what extent this was based on sympathy with the boycott versus the simple desire to have their staff present and working.[3] When the city pressured local insurance companies to stop insuring cars used in the carpools, the boycott leaders arranged policies with Lloyd's of London.

Black taxi drivers charged ten cents per ride, a fare equal to the cost to ride the bus, in support of the boycott. When word of this reached city officials on December 8, 1955, the order went out to fine any cab driver who charged a rider less than 45 cents. In addition to using private motor vehicles, some people used non-motorized means to get around, such as bicycling, walking, or even riding mules or driving horse-drawn buggies. Some people also raised their thumbs to hitchhike around. During rush hour, sidewalks were often crowded. As the buses received extremely few, if any, passengers, their officials asked the City Commission to allow stopping service to black communities.[4] Across the nation, black churches raised money to support the boycott and collected new and slightly used shoes to replace the tattered footwear of Montgomery's black citizens, many of whom walked everywhere rather than ride the buses and submit to Jim Crow laws.

In response, opposing members of the white community swelled the ranks of the White Citizens' Council, the membership of which doubled during the course of the boycott. Like the Ku Klux Klan, the Council members sometimes resorted to violence: Martin Luther King's and Ralph Abernathy's houses were firebombed, as were four Baptist churches. These hate groups often physically assaulted boycotters.

Under a 1921 ordinance, 156 protesters were arrested for "hindering" a bus, including King. He was ordered to pay a $500 fine or serve 3,855 days in jail. The move backfired by bringing national attention to the protest. King commented on the arrest by saying: "I was proud of my crime. It was the crime of joining my people in a nonviolent protest against injustice." [5]

The Montgomery Bus Boycott represented one of the first public victories of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and gave Martin Luther King the national attention that would make him one of the prime leaders of the cause. Rosa Parks became known as the "mother of the Civil Rights Movement" and lived a life of activism until her death on October 24, 2005.

United Farm Workers boycotts

The United Farm Workers of America (UFW) labor union evolved from unions founded in 1962 by CĂ©sar ChĂĄvez, Dolores Huerta, Larry Itliong, and Philip Veracruz. This union changed from a workers' rights organization that helped workers obtain unemployment insurance to a union of farm workers almost overnight when the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) went on strike in support of the mostly Filipino farm workers of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). Larry Itliong, who had previously initiated a grape strike on September 8th, 1965, led the fledgling organization's strike in Delano, California. The NFWA and the AWOC, recognizing their common goals and methods and realizing the strengths of coalition formation, jointly formed the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee. This organization eventually became the United Farm Workers and launched a boycott of table grapes that, after five years of struggle, finally won a contract with the major grape growers in California.

The UFW publicly adopted the principles of non-violence championed by Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. ÂĄSĂ, se puede! (Spanish for, "Yes, we can!") served as the official motto, exemplifying the organization's faith in the power of its people. ChĂĄvez used fasts both as means of drawing public attention to the union's cause and to assert control over a potentially unruly union. ChĂĄvez held steadfast to his convictions, maintaining that siding with the right cause would bring eventual victory: "There is enough love and good will in our movement to give energy to our struggle and still have plenty left over to break down and change the climate of hate and fear around us." [6]

The union prepared to launch its next major campaign in the orange fields in 1973 when a deal between the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and the growers nearly destroyed it. The growers signed contracts giving the Teamsters the right to represent the workers who had been members of the UFW. The UFW responded with strikes, lawsuits, and boycotts, including secondary boycotts in the retail grocery industry. The union struggled to regain the members it had lost in the lettuce field; it never fully recovered its strength in grapes, due in some part to incompetent management of the hiring halls it had established that seemed to favor some workers over others.

The battles in the fields sometimes became violent, with a number of UFW members killed on the picket line. In 1975 the violence prompted California to create an administrative agency, the Agricultural Labor Relations Board, to enforce a law modeled on the National Labor Relations Act that would channel these disputes into more peaceful forms. Years of demonstrating made the UFW a force to be reckoned with, and the Agricultural Labor Relations Board's new policies helped temper the actions of opponents.

Nestlé boycott

The Nestlé boycott was launched on July 4, 1977 in the United States against the Swiss-based Nestlé corporation. It soon spread rapidly outside the United States, particularly in Europe. Concern about the company's marketing of breast milk substitutes (infant formula), particularly in Third World countries, prompted the boycott.

Supporters of the boycott accused Nestlé of unethical methods of promoting infant formula over breast milk to poor mothers in Third World countries. Activists lobbied against hospitals' practice of passing out free powdered formula samples to mothers. After leaving the hospital, these mothers could no longer produce milk due to the substitution of formula feeding for breastfeeding. This forced the continued use of formula, which, when used improperly by excessive dilution or use of impure water, can contribute to malnutrition and disease. Additionally, since the formula was no longer free after leaving the hospital, the added expense could put a significant strain on the family's budget.

Nestlé's perceived marketing strategy was first written about in New Internationalist magazine in 1973 and in a booklet called The Baby Killer, published by the British non-governmental organization War On Want in 1974. Nestlé attempted to sue the publisher of a German-language translation (Third World Action Group). After a two-year trial, the court found in favor of Nestlé and fined the group 300 Swiss francs, because Nestlé could not be held responsible for the infant deaths "in terms of criminal law."

In May 1978, the U.S. Senate held a public hearing into the promotion of breast-milk substitutes in developing countries and joined calls for a Marketing Code. This was developed under the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and adopted by the World Health Assembly in 1981, as the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. The Code covers infant formula and other milk products, foods, and beverages, when marketed or otherwise represented to be suitable as a partial or total replacement of breast milk. It bans the promotion of breast milk substitutes and gives health workers the responsibility of advising parents. It limits manufacturing companies to the provision of scientific and factual information to health workers and sets out labeling requirements.

In 1984, boycott coordinators met with NestlĂ© and accepted the company's undertaking that it would abide by the Code, but the coordinators were not satisfied with NestlĂ©'s subsequent action and relaunched the boycott in 1988. Hundreds of European universities, colleges, and schools, including over 200 in the United Kingdom, banned the sale of NestlĂ© products from their shops and vending machines shortly thereafter. While the boycott garnered the most publicity and had the most courtroom victories within its first few years, its continuationâand, most importantly, the precedent it setâmade new generations of mothers aware of the advantages of breast milk over formula.

Olympic boycotts

The Olympic Games have been host to many boycotts, international in scope. The first Olympic boycotts occurred during the 1956 Summer Olympics. The British and French involvement in the Suez Crisis led to the absence of Egypt, Lebanon, and Iraq. Spain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland boycotted in opposition to the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Hungary and the Soviet Union were themselves present, which led to a hotly contested and violent water polo encounter, among others, between the two nations. In total, 45 Hungarians defected to the West after the Olympics. A third boycott came from the People's Republic of China, which protested against the presence of the Republic of China (under the name Formosa).

During a tour of South Africa by the All Blacks rugby team, Congo's official Jean Claude Ganga led a boycott of 28 African nations as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) refused to bar the New Zealand team from the 1976 Summer Olympics. Some of the nations (including Morocco, Cameroon, and Egypt) had already participated, however, so the teams only withdrew after the first day. From Southern and Central Africa, only Senegal and Ivory Coast took part. Both Iraq and Guyana also opted to join the Congolese-led boycott.

The United States (under President Jimmy Carter) boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics, held in Moscow that year, to protest the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan. The retaliatory boycott of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles occurred when the Soviet Union and 14 Eastern bloc countries refused to participate.

American track star Lacey O'Neal coined the term "girlcott" in the context of the protests by African American male athletes during the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. Speaking for black female athletes, she informed reporters that the group would not "girlcott" the Olympic Games as they had yet to be recognized as equals to male Olympians. "Girlcott" appeared in Time magazine in 1970 and later was used by retired tennis player Billie Jean King in The Times in reference to Wimbledon to emphasize her argument regarding equal pay for female players.

Legality and efficacy

While boycotts are generally legal in developed countries, some restrictions may apply. For instance, it may be unlawful for a union to order the boycott of companies that supply items to the organization. Secondary boycotts are illegal in many countries, including many states in the U.S. However, because American farm laborers are exempt, the United Farm Workers union has been able to legally use secondary boycotting of grocery store chains as an aid to their strikes and primary boycotts of California grapes and lettuce.

Sometimes the mere threat of a boycott brings about the intended result in a peaceful and expeditious manner. On the other hand, boycotts can last indefinitely, prompt unnecessary violence, and ultimately fail to achieve the intended goal(s). When analyzed as a means to an end, the efficacy of different boycotts varies immensely. Even though they employed tactics of nonviolent resistance, boycotters in the United Farm Workers Movement and the U.S. Civil Rights Movement suffered violent attacks by their opponents and even law enforcers. Such violence either prompts activists to reconsider their tactics of passive resistance, elevating the protest to a more aggressive form, or ends the boycott altogether.

Capitalism itself can also deter boycotts. Mergers and acquisitions lead to the formation of monopolies and effectively control the supply chain. This produces a plethora of various product names from the same company, where the manufacturer is not immediately obvious and leads to substantial limitations of consumer choice. For example, many restaurants worldwide effectively limit the choice of soft drinks to products of a single corporation, greatly reducing the likelihood of consumers boycotting such companies. Nestlé and its auxiliary companies, for example, have hundreds of products from bottled water to knives to candy bars. Although lists of products from various corporations being boycotted are available, to completely boycott such a company would require the consumer to not only remain up-to-date on product lists but also to do without many common household goods.

While a boycott usually serves as a bargaining tool, the publicity it generates can create momentum for larger movements. For example, the Montgomery Bus Boycottâalthough it had a direct effect on the social, political, and economic climate of Montgomeryâhelped garner national and international recognition for the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Further reading

- Raines, Howell. 1983. My Soul Is Rested, The Story Of The Civil Rights Movement In The Deep South. Penguin (Non-Classics; Reprint edition. ISBN 0140067531

- Branch, Taylor. 1988. Parting The Waters; America In The King Years 1954-63. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671460978

- King, Martin Luther Jr. 1987. Stride Toward Freedom. Harpercollins Childrens Books; Reprint edition. ISBN 0062504908

- Aldon, D. Morris. 1986. The Origins Of The Civil Rights Movement, Black Communities Organizing For Change. Free Press. ISBN 0029221307

- Williams, Juan. Eyes on The Prize, America's Civil Rights Years 1954-1965. ISBN 0140096531

- Ed. Clayborne Carson, David J. Garrow, Gerabld Gill, Vincent Harding, Darlene Clark Hine. Eyes on The Prize Civil Rights Reader, documents, speeches, and first hand accounts from the black freedom struggle. p. 45 - 60. ISBN 0140154035

- Nelson, Eugene. Huelga! The First One Hundred Days of the Delano Grape Strike.

- Gutierrez, David G. 1995. Walls and Mirrors. University of California Press: Berkeley.

- Farmworkers Reap Little as Union Strays From Its Roots, Part I of LA Times|LA Times series. January 8th, 2006

- 1993. "Cesar's Ghost: Rise and Fall of the UFW" in The Nation..

External links

All links retrieved November 20, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Boycott history

- Montgomery_Bus_Boycott history

- United_Farm_Workers history

- Nestlé_boycott history

- 1956_Summer_Olympics history

- 1976_Summer_Olympics history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.