Unemployment

Unemployment is the condition of willing workers lacking jobs or "gainful employment." In economics, unemployment statistics measure the condition and extent of joblessness within an economy. A key measure is the unemployment rate, which is the number of unemployed workers divided by the total civilian labor force.

Unemployment in an economic sense has proved a surprisingly difficult thing to define, let alone "cure." This is because there are many different types of unemployment, which overlap and so confound measurement and analysis. Some economists argue that full employment is the natural and desirable state of any healthy society. Marxists in particular claim that it is capitalism and the greed of the capitalists that causes unemployment to continue. Others have noted that certain types of unemployment are natural, such as seasonal unemployment for those working in fields where the amount of work fluctuates, or when new graduates and those returning to the workforce are seeking jobs.

In the ideal, everyone who wishes to work should be able to work, thus contributing to the larger society as well as receiving compensation that pays for their individual and family needs. This does not mean that every member of society works continuously; naturally some are training for new jobs, while others may have taken a break from the workforce for various reasons, and others are in the process of making a transition from one career or geographical location to a new one. Additionally, on the demand side, there may be times when employers need fewer workers, and so need to lay off some of the workforce temporarily. What is important for the health of society and the well-being of its members is that when people are unemployed that they have sufficient financial support to maintain themselves, and the opportunity to obtain new employment within a reasonable time frame. In an ideal society where all people live for the sake of others not simply for their personal benefit, unemployment problems can be minimized and each person can find the way to make their contribution to society.

Overview

Most economists believe that some unemployment will occur no matter what actions are taken by the government. This can be just because there will likely always someone looking for a job who cannot find one because of lack of skills, lack of availability of desirable positions, or being unwilling to move to a new location among other reasons. Some economists argue that unemployment is even necessary for a fully functioning economy as it is the result of useful re-aligning of priorities within the economy.

Marx and his followers have argued against keeping a "reserve army of the unemployed" based on the belief that unemployment is simply maintained to oppress laborers through needless competition. Many remedies for high rates of unemployment exist. Governments can offer military enlistment, people can engage in volunteer work, training can be given to help people qualify for new jobs, and relocation programs can be provided to assist people in meeting employment needs outside of their present geographical locale.

Types

Economists distinguish between five major kinds of unemployment: cyclical, frictional, structural, classical, and Marxian. Real-world unemployment may combine different types, such that all five might exist at one time. The magnitude of each is difficult to measure, because they overlap and are thus hard to separate from each other.

Cyclical unemployment

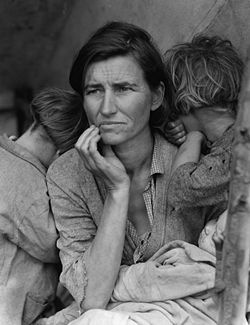

Cyclical unemployment exists due to inadequate effective aggregate demand. Its name is derived from its variation with the business cycle, though it can also be persistent, as during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Such unemployment results when Gross domestic product is not as high as potential output because of demand failure, due to (say) pessimistic business expectations which discourages private fixed investment spending. Low government spending or high taxes, underconsumption, or low exports compared to imports may also have this result.

Some consider this type of unemployment one type of frictional unemployment in which factors causing the friction are partially caused by some cyclical variables. For example, a surprise decrease in the money supply may shock participants in society. Then, we may see recession and cyclical unemployment until expectations adjust to the new conditions.

In this case, the number of unemployed workers exceeds the number of job vacancies, so that if even all open jobs were filled, some workers would remain unemployed. This kind of unemployment coincides with unused industrial capacity (unemployed capital goods). Keynesian economists see it as possibly being solved by government deficit spending or by expansionary monetary policy, which aims to increase non-governmental spending by lowering interest rates.

Classical economists reject the conception of cyclical unemployment as inevitable, seeing the attainment of full employment of resources and potential output as the normal state of affairs.

Frictional unemployment

Frictional unemployment involves people being temporarily between jobs, while searching for new ones; it is compatible with full employment. (It is sometimes called "search unemployment" and is seen as largely voluntary.) It arises because either employers fire workers or workers quit, usually because the individual characteristics of the workers do not fit the particular characteristics of the job (including matters of the employer's personal taste or the employee's inadequate work effort). Sometimes new entrants (such as graduating students) and re-entrants (such as former homemakers) suffer from spells of frictional unemployment.

Some employersâsuch as fast-food restaurants, chain stores, and job providers in secondary labor marketsâuse management strategies that rely on rapid turnover of employees, so that frictional unemployment is normal in these sectors.

This type of unemployment coincides with an equal number of vacancies and cannot be solved using aggregate demand stimulation. The best way to lower this kind of unemployment is to provide more and better information to job-seekers and employers, perhaps through centralized job-banks (as in some countries in Europe). In theory, an economy could also be shifted away from emphasizing jobs that have high turnover, perhaps by using tax incentives or worker-training programs.

But some frictional unemployment is beneficial, since it allows workers to obtain the jobs that best fit their wants and skills and the employers to find employees who promote profit goals the most. It is a small percentage of the unemployment, however, since workers can often search for new jobs while employedâand employers can seek new employees before firing current ones.

One kind of frictional unemployment is called "wait unemployment" and refers to the effects of the existence of some sectors where employed workers are paid more than the market-clearing equilibrium wage. Not only does this restrict the amount of employment in the high-wage sector, but it attracts workers from other sectors who "wait" to try to get jobs there. The main problem with this theory is that such workers will likely "wait" while having jobs, so that they are not counted as unemployed.

Another type of frictional unemployment is "seasonal unemployment" where specific industries or occupations are characterized by seasonal work which may lead to unemployment. Examples include workers employed during farm harvest times or those working winter jobs on the ski slopes or summer jobs such as life-guarding at pools and agricultural labor.

Structural unemployment

Structural unemployment involves a mismatch between the "good" workers looking for jobs and the vacancies available. Even though the number of vacancies may be equal to the number of the unemployed, the unemployed workers lack the skills needed for the jobsâor are in the wrong part of the country or world to take the jobs offered. It is a mismatch of skills and opportunities due to the structure of the economy changing. That is, it is very expensive to unite the workers with jobs. One possible example in the rich countries is the combination of the shortage of nurses with an excess labor supply in information technology. Unemployed programmers cannot easily become nurses, because of the need for new specialized training, the willingness to switch into the available jobs, and the legal requirements of such professions.

Structural unemployment is a result of the dynamic changes such as technological change and the fact that labor markets can never be as fluid as (say) financial markets. Workers are "left behind" due to costs of training and moving (such as the cost of selling one's house in a depressed local economy), plus inefficiencies in the labor markets, including discrimination.

Structural unemployment is hard to separate empirically from frictional unemployment, except to say that it lasts longer. It is also more painful. As with frictional unemployment, simple demand-side stimulus will not work to easily abolish this type of unemployment.

Some sort of direct attack on the problems of the labor marketâsuch as training programs, mobility subsidies, anti-discrimination policies, a Basic Income Guarantee, and/or a Citizen's Dividendâseems required. The latter provide a "cushion" of income which allows a job-seeker to avoid simply taking the first job offered and to find a vacancy which fits the worker's skills and interests. These policies may be reinforced by the maintenance of high aggregate demand, so that the two types of policy are complementary.

Structural unemployment may also be encouraged to rise by persistent cyclical unemployment: if an economy suffers from long-lasting low aggregate demand, it means that many of the unemployed become disheartened, while finding their skills (including job-searching skills) become "rusty" and obsolete. Problems with debt may lead to homelessness and a fall into the vicious circle of poverty. This means that they may not fit the job vacancies that are created when the economy recovers. The implication is that sustained high demand may lower structural unemployment. However, it also may encourage inflation, so some kind of incomes policies (wage and price controls) may be needed, along with the kind of labor-market policies mentioned in the previous paragraph. (This theory of rising structural unemployment has been referred to as an example of path dependence or "hysteresis.")

Much "technological unemployment" (such as due to the replacement of workers by robots) might be counted as structural unemployment. Alternatively, technological unemployment might refer to the way in which steady increases in labor productivity mean that fewer workers are needed to produce the same level of output every year. The fact that aggregate demand can be raised to deal with this problem suggests that this problem is instead one of cyclical unemployment. As indicated by Okun's Law, the demand side must grow sufficiently quickly to absorb not only the growing labor force but also the workers made redundant by increased labor productivity. Otherwise, we see a "jobless recovery" such as those seen in the United States in both the early 1990s and the early 2000s.

Seasonal unemployment might be seen as a kind of structural unemployment, since it is a type of unemployment that is linked to certain kinds of jobs (construction work, migratory farm work). The most-cited official unemployment measures erase this kind of unemployment from the statistics using "seasonal adjustment" techniques.

Classical unemployment

In the case of classical unemployment, like that of cyclical unemployment, the number of job-seekers exceeds the number of vacancies. However, the problem here is not aggregate demand failure. In this situation, real wages are higher than the market-equilibrium wage. In simple terms, institutions such as the minimum wage deter employers from hiring all of the available workers, because the cost would exceed the technologically-determined benefit of hiring them (the marginal product of labor). Some economists theorize that this type of unemployment can be reduced by increasing the flexibility of wages (such as by abolishing minimum wages or by employee protection), to make the labor market more like a financial market. Conversely, making wages more flexible allows employers who are adequately staffed to pay less with no corresponding benefit to job-seekers. If one accepts that people with low incomes spend their money rapidly (out of necessity), more flexible wages may increase unemployment in the short term.

Marxian unemployment

As Karl Marx claimed, some unemploymentâthe "reserve army of the unemployed"âis normally needed in order to maintain work discipline in jobs, keep wages down, and protect business profitability.[1] This point was later emphasized by economist Michal Kalecki.[2] If profitability suffers a sustained depression, capitalists can and will punish people by imposing a recession via their control over investment decisions (a capital strike). (Incidentally, in this section the term "capitalist" is used to refer to a person who owns and controls economic capital, whether or not she or he holds "capitalist" political or ethical views.) To the Marxian school, these strikes are rare, since in normal times the government, responding to pressure from their most important constituencies, will encourage recessions before profits are hurt.

As with cyclical and classical unemployment, with Marxian unemployment, the number of jobless exceeds the availability of vacancies. It is the scarcity of jobs that gives unemployment such a motivational effect. However, simple demand stimulus in the face of the capitalists' refusal to hire or invest simply encourages inflation: if profits are being squeezed, the only way to maintain high production is via rising prices.

To Marxists, this kind of unemployment cannot be abolished without overthrowing capitalism as an economic system and replacing it with democratic socialism.

A similar conception to this was advanced by Stiglitz and Shapiro (1983) when they considered shirking in employment. They concluded that unemployment is required to motivate workers to put effort into their work. This perhaps represents the incorporation of this idea into modern microfounded macroeconomics.

Full employment

In theory, it is possible to abolish cyclical unemployment by increasing the aggregate demand for products and workers. However, eventually the economy hits an "inflation barrier" imposed by the four other (supply-side) kinds of unemployment to the extent that they exist.

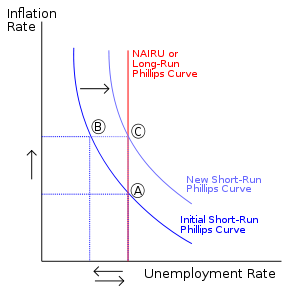

Some economists see the inflation barrier as corresponding to the natural rate of unemployment, where the "natural" rate of unemployment is defined as the rate of unemployment that exists when the labor market is in equilibrium and there is pressure for neither rising inflation rates nor falling inflation rates.[3] More scientifically, this rate is sometimes referred to as the NAIRU or the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment

This means that if the unemployment rate gets "too low," inflation will get worse and worse (accelerate) in the absence of wage and price controls (incomes policies). Others simply see the possibility of inflation rising as the unemployment rate falls. This is the famous Phillips curve.

One of the major problems with the NAIRU theory is that no-one knows exactly what the NAIRU is (while it clearly changes over time). The margin of error can be quite high relative to the actual unemployment rate, making it hard to use the NAIRU in policy-making.

Another, normative, definition of full employment might be called the ideal unemployment rate. It would exclude all types of unemployment that represent forms of inefficiency. This type of "full employment" unemployment would correspond to only frictional unemployment and would thus be very low. However, it would be impossible to attain this full-employment target using only demand-side Keynesian stimulus without getting below the NAIRU and suffering from accelerating inflation (absent incomes policies). Training programs aimed at fighting structural unemployment would help here.

Another problem for full employment is "graduate unemployment" in which all jobs for the educated have been filled, leaving a glut of overqualified people to compete for too few jobs.

Causes

There is considerable debate amongst economists as to what the main causes of unemployment are. Keynesian economics emphasizes unemployment resulting from insufficient effective demand for goods and service in the economy (cyclical unemployment). Others point to structural problems (inefficiencies) inherent in labor markets (structural unemployment). Classical or neoclassical economics tends to reject these explanations, and focuses more on rigidities imposed on the labor market from the outside, such as minimum wage laws, taxes, and other regulations that may discourage the hiring of workers (classical unemployment). Yet others see unemployment as largely due to voluntary choices by the unemployed (frictional unemployment). On the other extreme, Marxists see unemployment as a structural fact helping to preserve business profitability and capitalism (Marxian unemployment).

Though there have been several definitions of "voluntary" (and "involuntary") unemployment in the economics literature, a simple distinction is often applied. Voluntary unemployment is attributed to the individual unemployed workers (and their decisions), whereas involuntary unemployment exists because of the socio-economic environment (including the market structure, government intervention, and the level of aggregate demand) in which individuals operate. In these terms, much or most of frictional unemployment is voluntary, since it reflects individual search behavior. On the other hand, cyclical unemployment, structural unemployment, classical unemployment, and Marxian unemployment are largely involuntary in nature. However, the existence of structural unemployment may reflect choices made by the unemployed in the past, while classical unemployment may result from the legislative and economic choices made by labor unions and/or political parties. So in practice, the distinction between voluntary and involuntary unemployment is hard to draw. The clearest cases of involuntary unemployment are those where there are fewer job vacancies than unemployed workers even when wages are allowed to adjust, so that even if all vacancies were to be filled, there would be unemployed workers. This is the case of cyclical unemployment and Marxian unemployment, for which macroeconomic forces lead to microeconomic unemployment.

Some say that one of the main causes of unemployment in a free market economy is the fact that the law of supply and demand is not really applied to the price to be paid for employing people. In situations of falling demand for products and services the wages of all employees (from president to errand boy) are not automatically reduced by the required percentage to make the business viable. Others say that it is the market that determines the wages based on the desirability of the job. The more people qualified and interested in the job, the lower the wages for that job become. Based on this view, the profitability of the company is not a factor in determining whether or not the work is profitable to the employee. People are laid off, because pay reductions would reduce the number of people willing to work a job. With fewer people interested in a particular job, the employees' bargaining power would actually rise to stabilize the situation, but their employer would be unable to fulfill their wage expectations. In the classical framework, such unemployment is due to the existing legal framework, along with interferences with the market by non-market institutions such as labor unions and government. Others say many of the problems with market adjustment arise from the market itself (Keynes) or from the nature of capitalism (Marx).

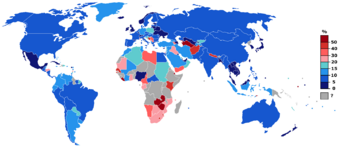

In developing countries, unemployment is often caused by burdensome government regulation. The World Bank's Doing Business project shows how excessive labor regulation increases unemployment among women and youths in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.[4]

Effects

Individual costs

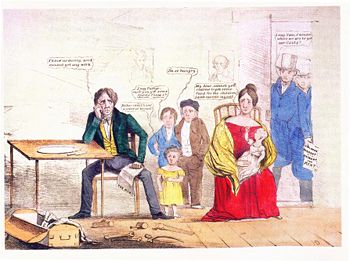

In the absence of a job when a person needs one, it can be difficult to meet financial obligations such as purchasing food to feed oneself and one's family, and paying one's bills; failure to make mortgage payments or to pay rent may lead to homelessness through foreclosure or eviction. Being unemployed, and the financial difficulties and loss of health insurance benefits that come with it, may cause malnutrition and illness, and are major sources of mental stress and loss of self-esteem which may lead to depression, which may have a further negative impact on health.

Lacking a job often means lacking social contact with fellow employees, a purpose for many hours of the day, lack of self-esteem, mental stress and illness, and of course, the inability to pay bills and to purchase both necessities and luxuries. The latter is especially serious for those with family obligations, debts, and/or medical costs, where the availability of health insurance is often linked to holding a job. Rising unemployment increases the crime rate, the suicide rate, and causes a decline in healthiness.[5]

Another cost for the unemployed is that the combination of unemployment, lack of financial resources, and social responsibilities may push unemployed workers to take jobs that do not fit their skills or allow them to use their talents. That is, unemployment can cause underemployment. This is one of the economic arguments in favor of having unemployment insurance.

This feared "cost of job loss" can spur psychological anxiety, weaken labor unions and their members' sense of solidarity, encourage greater work-effort and lower wage demands, and/or abet protectionism. This last means efforts to preserve existing jobs (of the "insiders") via barriers to entry against "outsiders" who want jobs, legal obstacles to immigration, and/or tariffs and similar trade barriers against foreign competitors. The impact of unemployment on the employed is related to the idea of Marxian unemployment. Finally, the existence of significant unemployment raises the oligopsony power of one's employer: that raises the cost of quitting one's job and lowers the probability of finding a new source of livelihood.

Economic benefits of unemployment

Unemployment may have advantages as well as disadvantages for the overall economy. Notably, it may help avert runaway inflation, which negatively affects almost everyone in the affected economy and has serious long-term economic costs. However the historic assumption that full local employment must lead directly to local inflation has been attenuated, as recently expanded international trade has shown itself able to continue to supply low-priced goods even as local employment rates rise closer to full employment.

The inflation-fighting benefits to the entire economy arising from a presumed optimum level of unemployment have been studied extensively. Before current levels of world trade were developed, unemployment was demonstrated to reduce inflation, following the Phillips curve, or to decelerate inflation, following the NAIRU/natural rate of unemployment theory.

Beyond the benefits of controlled inflation, frictional unemployment provides employers a larger applicant pool from which to select employees better suited to the available jobs. The unemployment needed for this purpose may be very small, however, since it is relatively easy to seek a new job without losing one's current one. And when more jobs are available for fewer workers (lower unemployment), it may allow workers to find the jobs that better fit their tastes, talents, and needs.

As in the Marxian theory of unemployment, special interests may also benefit: some employers may expect that employees with no fear of losing their jobs will not work as hard, or will demand increased wages and benefit. According to this theory, unemployment may promote general labor productivity and profitability by increasing employers' monopsony-like power (and profits).

Optimal unemployment has also been defended as an environmental tool to brake the constantly accelerated growth of the GDP to maintain levels sustainable in the context of resource constraints and environmental impacts. However the tool of denying jobs to willing workers seems a blunt instrument for conserving resources and the environmentâit reduces the consumption of the unemployed across the board, and only in the short-term. Full employment of the unemployed workforce, all focused toward the goal of developing more environmentally efficient methods for production and consumption might provide a more significant and lasting cumulative environmental benefit and reduced resource consumption. If so, the future economy and workforce would benefit from the resultant structural increases in the sustainable level of GDP growth.

Aiding the unemployed

The most developed countries have aids for the unemployed as part of the welfare state. These unemployment benefits include unemployment insurance, welfare, unemployment compensation, and subsidies to aid in retraining. The main goal of these programs is to alleviate short-term hardships and, more importantly, to allow workers more time to search for a good job.

In the United States, the New Deal made relief of the unemployed a high priority, with many different programs. The goal of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was to employ most of the unemployed people on relief until the economy recovered.

In the United States today, the unemployment insurance allowance one receives is based solely on previous income (not time worked, family size, or other such factors) and usually compensates for one-third of one's previous income. In cases of highly seasonal industries the system provides income to workers during the off seasons, thus encouraging them to stay attached to the industry.

Notes

- â David L. Prychitko, Marxism Library of Economics & Liberty. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- â Michal Kalecki. New School.

- â Natural Rate of Unemployment Economics Help. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- â Doing Business World Bank. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- â Fact sheet on the impact of unemployment Virginia Tech, Department of Economics. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bix, Amy Sue. 2001. Inventing Ourselves Out of Jobs?: America's Debate over Technological Unemployment, 1929â1981. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801869137

- Crane, David. 1981. Beyond the Monetarists: Post-Keynesian Alternatives to Rampant Inflation, Low Growth and High Unemployment. Lorimer. ISBN 0888625014

- Gallie, Duncan. 2004. Resisting Marginalization: Unemployment Experience and Social Policy in the European Union. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199271844

- Jossa, Bruno. 1998. Inflation, Unemployment and Money: Interpretations of the Phillips Curve. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 1858984572

- Sautter, Udo. 2003. Three Cheers for the Unemployed: Government and Unemployment before the New Deal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521533279

- Vedder, Richard. 1997. Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America. New York University Press. ISBN 0814787924

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.