Difference between revisions of "Hieroglyph" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (71 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Archaeology]] | [[Category:Archaeology]] | ||

| Line 4: | Line 5: | ||

[[Category:Linguistics]] | [[Category:Linguistics]] | ||

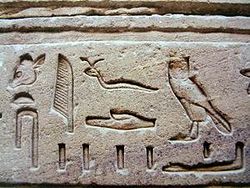

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Egypt Hieroglyphe4.jpg|right|250px|thumb|Egyptian hieroglyphs typical of the Graeco-Roman period, sculpted in Relief.]] |

| + | A '''hieroglyph''' is a character used in a pictorial [[writing system]]. The term derives from the [[Greek language|Greek]] term for “sacred carving,” translated from the Egyptian phrase “the god’s words.” The term originally referred only to the [[Egyptian hieroglyphs]], but was later also applied to ancient [[Crete|Cretan]], [[Anatolia|Luwian]], [[Mayan Civilization|Mayan]] and [[Mi'kmaq]] scripts. However, there is no connection between Egyptian hieroglyphs and other hieroglyphic scripts; they evolved independently of one another. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Hieroglyphs were a significant development in human history, the beginnings of written [[language]]. While spoken language allows [[communication]] among those present, and to some extent to later generations through [[oral tradition]], written language allows communication at a distance both geographically and over time. This allows a [[culture]] to make significant advances in [[knowledge]] both of the physical world through [[science]] and of the inner world of [[mind]] and [[spirit]] through [[philosophy|philosophical]] and [[theology|theological]] inquiry. Contemporary [[alphabet]]s have advantages over hieroglyphs such as ease of [[learning]], the ability to express new ideas without requiring new characters, and they lend themselves to [[typography]] and [[printing]] and thus to mass distribution of written material to the general public. Despite appearing "primitive" in comparison, the various developments of hieroglyphs around the world constituted major advances in the development of humankind. | ||

| − | + | ==Etymology== | |

| + | The word hieroglyph derives from the Greek words ἱερός (hierós "sacred") and γλύφειν (glúphein "to carve" or "to write," as in the term "glyph." This was translated from the Egyptian phrase “the god’s words,” a phrase derived from the Egyptian practice of using hieroglyphic writing predominantly for religious or sacred purposes. | ||

| − | + | The term “hieroglyphics,” used as a noun, was once common, but now denotes more informal usage. In academic circles, the term “hieroglyphs” has replaced “hieroglyphic” to refer to both the language as a whole and the individual characters that compose it. “Hieroglyphic” is still used as an adjective (as in a hieroglyphic writing system). | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | ==Characteristics== | |

| + | Hieroglyphs are characters composed of graphical figures. Often, hieroglyphic [[symbol]]s are readily recognizable as an everyday physical object, such as a person, a [[tool]], the [[sun]], or an [[animal]]. In many cases, symbols stand for the object they represent, but they can also be used to represent a concept associated with the object (such as "day" for "sun") or a phonetic sound associated with the object's name. | ||

| − | + | A single system of hieroglyphic writing can use a combination of [[phonetic]] and [[logographic]] symbols. Many hieroglyphic scripts later evolved into more simplified forms, and may have formed the basis for a number of linear scripts, such as [[Linear A]] and [[Linear B]]. | |

| − | == | + | ==Major hieroglyphic writing systems== |

| + | It should be noted that while these diverse [[writing system]]s are all classified as "hieroglyphs," no connection in their development is implied. Generally, they emerged in different areas of the globe and at different times in human history. Even when a possible connection between the [[culture]]s occurred, suggesting that the concept of [[writing]] might have been borrowed by one from the other, the use of signs in these different hieroglyphic systems shows no evidence of a connection other than the use of certain symbols universally understood (such as a circle for the sun). | ||

===Egyptian hieroglyphs=== | ===Egyptian hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Egyptian hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Egyptian hieroglyphs}} | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:800px-Pyramid Texts Teti I.JPG|thumb|250 px|Pyramid Texts from Pyramid of [[Teti I]] in [[Saqqara]]]] |

| − | + | [[Egyptian hieroglyphs]] are perhaps the most well-known hieroglyphic [[writing system]], and the one from which the term “hieroglyph” originated. | |

| − | + | This formal [[writing system]] used by the [[ancient Egypt]]ians consists of a combination of [[phonetic]] signs, [[ideogram]]s, and [[determinative]]s. Phonetic signs work like letters of an [[alphabet]]: a single sign stands for a letter (or combination of letters). Ideograms are made from signs that are accompanied by a vertical line, which indicates that the sign stands for the object it represents. Determinatives appear, when needed, at the end of a word, and give a clue as to the meaning of a word.<ref>Jim Loy, [http://www.jimloy.com/hiero/types.htm Types of Signs in Egyptian], Jim Loy's Egyptian Hieroglyphics and Egyptology Page, 2002. Retrieved December 8, 2008.</ref> | |

| − | + | Egyptian hieroglyphs were used mainly for formal, religious inscriptions (hence their name, which translates to “the god’s words”). Everyday writing, such as record keeping or letter writing, used the [[Hieratic]] script, a simplified version of hieroglyphic writing. Hieratic script is structurally the same as hieroglyphic writing, but people, animals, and objects are no longer recognizable. | |

| − | + | [[Image:NarmerPalette ROM-gamma.jpg|250px|thumb|[[Obverse|Reverse]] and Obverse Sides of Narmer Palette, this facsimile on display at the [[Royal Ontario Museum]], in [[Toronto]], [[Canada]]]] | |

| − | [[Image: | + | One of the oldest and most famous examples of Egyptian hieroglyphs can be found on the [[Narmer Palette]], a [[shield]] shaped palette that dates to around 3200 B.C.E. The Narmer Palette has been described as "the first historical document in the world".<ref>Bob Brier, ''Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians'' (Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 0313303134), 202.</ref>The palette was discovered in 1898 by [[archaeologist]]s [[James E. Quibell]] and [[Frederick W. Green]] in the ancient city of [[Nekhen]] (currently Hierakonpolis), believed to be the Pre-Dynastic capital of Upper Egypt. The palette is believed to be a gift offering from King [[Narmer]] to the god [[Amun]]. Narmer’s name is written at the top on both the front and back of the palette.<ref> Francesca Jourdan, [http://www.ptahhotep.com/articles/Narmer_palette.html "The Narmer Palette,"] ''InScription, Journal of Ancient Egypt'' (7) (2000). Retrieved December 8, 2008.</ref> |

| − | + | The [[Rosetta Stone]], discovered in 1799, was instrumental in the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. The Rosetta Stone contained three translations of a priestly decree: one in Egyptian hieroglyphic script, one in [[Demotic (Egyptian)|demotic]] (the everyday Egyptian script), and the third in [[Ancient Greek|Greek]]. Knowledge of the meaning of hieroglyphs had long since disappeared, but Greek was a well known language, and translators were able to use this text to reveal the structure and meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphs. | |

| − | + | Egyptian hieroglyphic writing used a core of about 800 hieroglyphs. This number varied; during the [[Greco-Roman]] period, more than 5,000 hieroglyphs were in use.<ref>Antonio Loprieno, ''Ancient Egyptian; A Linguistic Introduction'' (Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0521448492), 12. </ref> Interestingly, hieroglyphic writing did not incorporate vowel sounds. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Cretan hieroglyphs=== | ===Cretan hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Cretan hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Cretan hieroglyphs}} | ||

| − | '''Cretan hieroglyphs''' | + | '''Cretan hieroglyphs''' were discovered by the [[archaeologist]] Sir [[Arthur Evans]], who is perhaps most well known for his excavations of the palace he named [[Knossos]] at [[Crete]], as well as the discovery of the [[Minoan civilization]] that inhabited it. Cretan hieroglyphs are the first of three scripts discovered at Knossos, and are thought to date to around 2000 B.C.E.. The script was found on [[Bronze Age]] [[clay]] tablets and sealstones at Knossos, as well as artifacts from the Minoan Palace at [[Petras]] in eastern Crete. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The Cretan hieroglyphic script contains over 100 pictograms, including representations of a [[lyre]], [[carpentry|carpenter]]’s tools, [[dog]] heads, and [[bee]]s.<ref>Arthur J. Evans, "Writing in Prehistoric Greece," ''The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland'' 30 (1900): 91-93.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Later scripts, known as [[Linear A]] and [[Linear B]], may have evolved from these hieroglyphs. Linear A is thought to date to 1850-1700 B.C.E.; the original [[pictogram]]s present in the hieroglyphic script have been reduced to a more linear form.<ref> Athena Publications, [http://www.athenapub.com/11mnwrit.htm "Bronze Age Writing on Crete: Hieroglyphs, Linear A, and Linear B,"] ''Athena Review'' 3(3) (2003):21. Retrieved January 14, 2009.</ref> | ||

===Anatolian hieroglyphs=== | ===Anatolian hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Anatolian hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Anatolian hieroglyphs}} | ||

[[Image:Troy VIIb hieroglyphic seal reverse.png|thumb|160px|Drawing of the hieroglyphic seal found in the [[Troy VIIb]] layer.]] | [[Image:Troy VIIb hieroglyphic seal reverse.png|thumb|160px|Drawing of the hieroglyphic seal found in the [[Troy VIIb]] layer.]] | ||

| − | '''Anatolian hieroglyphs''' | + | '''Anatolian hieroglyphs''' were used in [[Anatolia]], as well as parts of modern [[Syria]] during the second and third millennia B.C.E. They were once commonly known as [[Hittite]] hieroglyphs, as one of the first discovered uses of the script was on personal seals from the ancient Hittite capital, Hattusha. The language represented is [[Luwian]] (sometimes spelled “Luvian”,) not [[Hittite language|Hittite]], and the term '''Luwian hieroglyphs''' is often used in English publications. It is possible that the hieroglyphs used on Hittite personal [[Seal (device)|seal]]s were used in a symbolic nature and were not intended to represent language, but rather concepts such as names, titles, or good luck symbols.<ref>Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, [http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/Melchert/hluvianscript.pdf The World’s Writing Systems] (Oxford University Press, 1996), 120. Retrieved January 14, 2009.</ref> |

| + | Anatolian hieroglyphs utilize both [[logograph]]ic and [[phonograph]]ic elements, as well as the use of logographic elements that have a phonetic compliment. Most of the signs are pictorial in nature, representing human figures, plants, animals, and everyday objects. Text is most commonly arranged horizontally, beginning in a top corner and working its way down the page in alternating left-to-right/right-to-left registers. This practice was called ''[[boustrophedon]]'' by the [[Ancient Greek|Greeks]], meaning "as the ox turns" (when [[plow]]ing a field). Within each register, signs are arranged vertically in columns. There are no word breaks, although a word divider sign is sometimes found.<ref>Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, [http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/Melchert/hluvianscript.pdf The World’s Writing Systems] (Oxford University Press, 1996), 121-123. Retrieved January 14, 2009.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Dongba script=== | |

| + | {{Main|Dongba script}} | ||

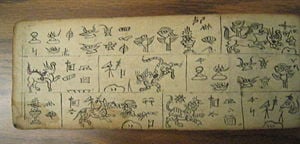

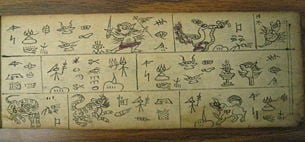

| + | [[Image:Painted Naxi panel.jpeg|thumb|250 px|right|An old Naxi painted storyboard]] | ||

| + | The '''Dongba''' script is a [[pictograph]]ic writing system used by the priests of the [[Naxi people]], an ethnic minority found mainly near the [[Yangtze River]] in [[China]] as well as in [[Tibet]]. The Dongba script is unique in that it is the only living pictographic language in the world; Naxi priests still use the Dongba script to create manuscripts for ceremonies like [[funeral]]s and blessings.<ref>Mi Chu Wiens, [http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/9906/naxi1.html "Living Pictographs:Asian Scholar Unlocks Secrets of the Naxi Manuscripts,"] ''Library of Congress Information Bulletin'' 58(6) (June 1999). Retrieved December 8, 2008.</ref> | ||

| − | The | + | The origin of the Dongba script is a matter of [[legend]] and debate. It is likely that the script has been in use for close to 1,000 years, and was widely used by the tenth century. Both the Naxi language and script were suppressed after the [[Communism|Communist]] victory and during China’s [[Cultural Revolution]] in the 1960s, but efforts have been made to revive interest in the language. |

| + | The Dongba script consists of about 1,400 symbols. Ninety percent of these are pictograms, although some are used to represent phonetic values. The Naxi language is also written using [[Geba script|Geba]] (a script more similar to [[Chinese character]] writing) or a [[Latin alphabet]] writing system based on [[Pinyin]].<ref name=ager>Simon Ager, [http://www.omniglot.com/writing/naxi.htm "Naxi Scripts,"] Omniglot, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2008.</ref> | ||

| − | + | {| | |

| − | + | |+ align=bottom| ''Facing pages of a Naxi manuscript, displaying both pictographic ''dongba'' and smaller syllabic ''geba.'' | |

| − | + | | [[Image:Naxi manuscript (left) 2087.jpg|300px]]||[[Image:Naxi manuscript (right) 2088.jpg|305px]] | |

| − | + | |} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:NaranjoStela10Maler.jpg|160px|right|thumb|An inscription in Maya glyphs from the site of [[Naranjo]], relating to the reign of king ''Itzamnaaj K'awil'', 784-810.]] | |

===Mayan hieroglyphs=== | ===Mayan hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Mayan hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Mayan hieroglyphs}} | ||

| − | The ''' | + | The '''Mayan script''', also known as '''Mayan hieroglyphs''', was the [[writing system]] of the [[pre-Columbian]] [[Mayan civilization]] of [[Mesoamerica]]. It consisted of a highly elaborate set of [[glyph]]s, which were laboriously painted on [[ceramic]]s, walls, or bark-paper [[codex|codices]], carved in wood or stone, or molded in [[stucco]]. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The Mayan script is made up of about 550 [[logogram]]s (representing whole words), 150 syllabic glyphs (representing [[syllable]]s), as well as glyphs for the names of places and gods. Thus, Mayan writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern [[Japanese writing]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | Maya | + | For much of modern history, it was commonly believed that the Mayan script was not a complete writing system, and did not actually represent a language. In the 1950s, however, [[Russia]]n [[ethnology|ethnologist]] [[Yuri Knorozov]] suggested that the script was partly phonetic and represented the Yucatec Mayan language. The [[Yucatán|Yucatec]] Maya had actually used the script up until the sixteenth century. As a result of Knorozov's insight, many Mayan texts can now be interpreted.<ref name=ager/> |

| − | + | While the earliest known Mayan script is dated around 250 B.C.E.., the script may have been developed much earlier. The Mayan civilization itself may have developed as early as 3000 B.C.E.. Until recently it was thought that the Maya may have adopted writing from the [[Olmec]] or [[Epi-Olmec script]].<ref>Linda Schele and David Friedel, ''A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya'' (New York, NY: William Morrow, 1990, ISBN 0688074561).</ref> Other related and nearby Mesoamerican cultures of the period were also heirs to the Olmec writing system, and developed parallel systems which shared key attributes (such as the base-twenty [[numeral system|numerical system]] written with a system of bars and dots). However, it is generally believed that the Maya developed the only complete writing system in [[Mesoamerica]], meaning that they were the only civilization that could write everything they could say. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Olmec hieroglyphs=== | ===Olmec hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Olmec hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Olmec hieroglyphs}} | ||

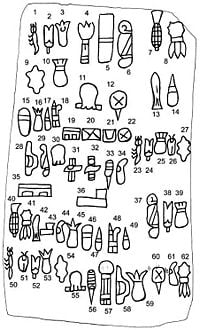

| − | [[Image:Cascajal-text.jpg| | + | [[Image:Cascajal-text.jpg|left||200px|thumb|The 62 glyphs of the Cascajal Block]] |

| − | + | The [[Olmec]] civilization was one of the first complex societies in early [[Mesoamerica]], dating from 1500 B.C.E. through 100 B.C.E., and possibly even later. Although it was known that Olmec culture was full of accomplishments in [[art]], [[mathematics]], and [[engineering]], including [[drainage system]]s and accurate [[calendar]]s, it was not until the [[Cascajal Block]] was discovered in 1999 that there was any evidence of a true Olmec [[writing system]]. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The Cascajal Block was discovered by road builders in a pile of debris near [[Veracruz]] lowlands in the ancient [[Olmec heartland]]. The slab of rock is carved with 62 signs and dates to the early first millennium B.C.E. The block weighs approximately {{convert|26|lb}}, and is {{convert|36|cm}} by {{convert|21|cm}}. The nature of the signs, their sequencing patterns, and consistent reading order are all indications that the tablet is an example of a Olmec writing system. | ||

| + | The symbols on the Cascajal block, some of which resemble plants, such as [[corn]] and [[ananas]], or animals, such as [[insect]]s and [[fish]], are unlike those of any other writing system in Mesoamerica. The Cascajal block is also unusual because the symbols apparently run in horizontal rows and "there is no strong evidence of overall organization. The sequences appear to be conceived as independent units of information."<ref>Joel Skidmore, [http://mesoweb.com/reports/Cascajal.pdf "The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing,"] Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2009. </ref> All other known Mesoamerican scripts typically use vertical rows. | ||

===Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing=== | ===Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing=== | ||

| − | {{Main |Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing}} | + | {{Main|Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing}} |

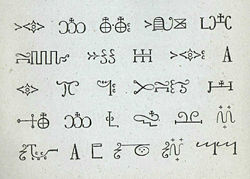

| − | + | [[Image:Mikmaq sample (ave Maria).jpg|thumb|250 px|right|A sample of Mi'kmaq "hieroglyphic" writing, the Ave Maria.]] | |

| + | [[Mí'kmaq hieroglyphic writing]] was used by the [[Mí'kmaq]] [[Native Americans]], native to [[Nova Scotia]] and its surrounding areas. | ||

| − | = | + | The Mi’kmaq script primarily consists of a collection of [[ideogram]]s. The Mi’kmaq had a rich oral tradition, and it has been suggested that hieroglyphs were used as either a [[memory]] aid or for trail marking. Since written language was not a major part of Mi’kmaq life, the ideograms eventually fell out of use, and were eventually replaced by phonetic versions of the Mi’kmaq language using the [[Latin alphabet]].<ref name=mikmaq>[http://www.muiniskw.org/pgCulture4a.htm "About Mi’Kmaw 'Hieroglyphics',"] Mi’kmaq Spirit, 2007. Retrieved January 14, 2008.</ref> |

| − | |||

| + | [[Father le Clercq]], a [[Roman Catholic]] [[missionary]] on the [[Gaspé Peninsula]], noted in 1691 that he had seen some Mí'kmaq children writing with [[charcoal]] [[birch bark document|symbols on birchbark]] while he taught them [[prayer]]s. This and other accounts of writing that pre-date missionary visits serve to refute claims that the Mi’kmaq writing system was developed by missionaries as a way to teach Christian prayers. Missionaries worked to understand and develop the writing system into a fully functional written language in order to translate prayers like ''[[The Lord’s Prayer]]'', adding new ideograms to refer to concepts like [[God]] (a triangle to represent the [[trinity]].<ref name=mikmaq/> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 155: | Line 101: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | *Betro, Maria C. ''Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt'' Abbeville Press, 1996. ISBN 0789202328 | |

| − | * | + | *Harris, John F. and Stephen K. Stearns. ''Understanding Maya Inscriptions: A Hieroglyph Handbook,'' University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1997. ISBN 0924171413 |

| − | * | + | *Loprieno, Antonio. ''Ancient Egyptian; A Linguistic Introduction.'' Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0521448492 |

| − | + | *Mercer, Samuel and Janice Kamrin. ''The Handbook of Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Study of the Ancient Language.'' Hippocrane Books, 1998. ISBN 0781806259 | |

| − | + | *Pool, Christopher. ''Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica.'' Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0521783127 | |

| − | + | *Robinson, Andrew. ''The story of writing with over 350 illustrations, 50 in color.'' New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500281564 | |

| − | * | + | *Schele, Linda, and David Friedel. ''A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya.'' New York, NY: William Morrow, 1990. ISBN 0688074561 |

| − | + | *Schmidt, David L., and Murdena Marshall. 1995. ''Míkmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America's First Indigenous Script.'' Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 1551090694 | |

| − | * | + | *Skidmore, Joel. [http://mesoweb.com/reports/Cascajal.pdf "The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing,"] Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2009. |

| − | + | *Stawell, F. Melian. ''Clue to the Cretan Scripts.'' Kessinger Publishing, LLC., 2003. ISBN 0766128415 | |

| − | * | + | *Wilford, John Noble. [http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2006/09/15/MNGS8L68QT1.DTL "3,000-year-old script on stone found in Mexico,"] ''San Francisco Chronicle'', September 15, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2009. |

| − | + | *Woodard, Roger D. ''The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor.'' Cambridge University Press, 2008. ISBN 052168496X | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved December 24, 2017. | ||

*[http://people.ku.edu/~jyounger/Hiero/ The Cretan Hieroglyphic Texts] | *[http://people.ku.edu/~jyounger/Hiero/ The Cretan Hieroglyphic Texts] | ||

| + | *[http://www.ancientscripts.com/luwian.html Luwian] | ||

| + | *[http://www.evertype.com/gram/olmec.html Analysis of Olmec Hieroglyphs] | ||

| + | *[http://www.christusrex.org/www1/pater/JPN-micmac.html Micmac at ChristusRex.org] – A large collection of scans of prayers in Míkmaq hieroglyphs. | ||

| − | + | {{credits|Hieroglyph|263692965|Cursive_hieroglyphs|241581144|Dongba_script|255768794|Cretan_hieroglyphs|253351258|Anatolian_hieroglyphs|252917179|Maya_script|251426098|Cascajal_Block|255354058|Isthmian_script|249002243|Mi'kmaq_hieroglyphic_writing|233987806}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{credits| | ||

Latest revision as of 15:47, 25 January 2023

A hieroglyph is a character used in a pictorial writing system. The term derives from the Greek term for “sacred carving,” translated from the Egyptian phrase “the god’s words.” The term originally referred only to the Egyptian hieroglyphs, but was later also applied to ancient Cretan, Luwian, Mayan and Mi'kmaq scripts. However, there is no connection between Egyptian hieroglyphs and other hieroglyphic scripts; they evolved independently of one another.

Hieroglyphs were a significant development in human history, the beginnings of written language. While spoken language allows communication among those present, and to some extent to later generations through oral tradition, written language allows communication at a distance both geographically and over time. This allows a culture to make significant advances in knowledge both of the physical world through science and of the inner world of mind and spirit through philosophical and theological inquiry. Contemporary alphabets have advantages over hieroglyphs such as ease of learning, the ability to express new ideas without requiring new characters, and they lend themselves to typography and printing and thus to mass distribution of written material to the general public. Despite appearing "primitive" in comparison, the various developments of hieroglyphs around the world constituted major advances in the development of humankind.

Etymology

The word hieroglyph derives from the Greek words ἱερός (hierós "sacred") and γλύφειν (glúphein "to carve" or "to write," as in the term "glyph." This was translated from the Egyptian phrase “the god’s words,” a phrase derived from the Egyptian practice of using hieroglyphic writing predominantly for religious or sacred purposes.

The term “hieroglyphics,” used as a noun, was once common, but now denotes more informal usage. In academic circles, the term “hieroglyphs” has replaced “hieroglyphic” to refer to both the language as a whole and the individual characters that compose it. “Hieroglyphic” is still used as an adjective (as in a hieroglyphic writing system).

Characteristics

Hieroglyphs are characters composed of graphical figures. Often, hieroglyphic symbols are readily recognizable as an everyday physical object, such as a person, a tool, the sun, or an animal. In many cases, symbols stand for the object they represent, but they can also be used to represent a concept associated with the object (such as "day" for "sun") or a phonetic sound associated with the object's name.

A single system of hieroglyphic writing can use a combination of phonetic and logographic symbols. Many hieroglyphic scripts later evolved into more simplified forms, and may have formed the basis for a number of linear scripts, such as Linear A and Linear B.

Major hieroglyphic writing systems

It should be noted that while these diverse writing systems are all classified as "hieroglyphs," no connection in their development is implied. Generally, they emerged in different areas of the globe and at different times in human history. Even when a possible connection between the cultures occurred, suggesting that the concept of writing might have been borrowed by one from the other, the use of signs in these different hieroglyphic systems shows no evidence of a connection other than the use of certain symbols universally understood (such as a circle for the sun).

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs are perhaps the most well-known hieroglyphic writing system, and the one from which the term “hieroglyph” originated.

This formal writing system used by the ancient Egyptians consists of a combination of phonetic signs, ideograms, and determinatives. Phonetic signs work like letters of an alphabet: a single sign stands for a letter (or combination of letters). Ideograms are made from signs that are accompanied by a vertical line, which indicates that the sign stands for the object it represents. Determinatives appear, when needed, at the end of a word, and give a clue as to the meaning of a word.[1]

Egyptian hieroglyphs were used mainly for formal, religious inscriptions (hence their name, which translates to “the god’s words”). Everyday writing, such as record keeping or letter writing, used the Hieratic script, a simplified version of hieroglyphic writing. Hieratic script is structurally the same as hieroglyphic writing, but people, animals, and objects are no longer recognizable.

One of the oldest and most famous examples of Egyptian hieroglyphs can be found on the Narmer Palette, a shield shaped palette that dates to around 3200 B.C.E. The Narmer Palette has been described as "the first historical document in the world".[2]The palette was discovered in 1898 by archaeologists James E. Quibell and Frederick W. Green in the ancient city of Nekhen (currently Hierakonpolis), believed to be the Pre-Dynastic capital of Upper Egypt. The palette is believed to be a gift offering from King Narmer to the god Amun. Narmer’s name is written at the top on both the front and back of the palette.[3]

The Rosetta Stone, discovered in 1799, was instrumental in the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. The Rosetta Stone contained three translations of a priestly decree: one in Egyptian hieroglyphic script, one in demotic (the everyday Egyptian script), and the third in Greek. Knowledge of the meaning of hieroglyphs had long since disappeared, but Greek was a well known language, and translators were able to use this text to reveal the structure and meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Egyptian hieroglyphic writing used a core of about 800 hieroglyphs. This number varied; during the Greco-Roman period, more than 5,000 hieroglyphs were in use.[4] Interestingly, hieroglyphic writing did not incorporate vowel sounds.

Cretan hieroglyphs

Cretan hieroglyphs were discovered by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, who is perhaps most well known for his excavations of the palace he named Knossos at Crete, as well as the discovery of the Minoan civilization that inhabited it. Cretan hieroglyphs are the first of three scripts discovered at Knossos, and are thought to date to around 2000 B.C.E. The script was found on Bronze Age clay tablets and sealstones at Knossos, as well as artifacts from the Minoan Palace at Petras in eastern Crete.

The Cretan hieroglyphic script contains over 100 pictograms, including representations of a lyre, carpenter’s tools, dog heads, and bees.[5]

Later scripts, known as Linear A and Linear B, may have evolved from these hieroglyphs. Linear A is thought to date to 1850-1700 B.C.E.; the original pictograms present in the hieroglyphic script have been reduced to a more linear form.[6]

Anatolian hieroglyphs

Anatolian hieroglyphs were used in Anatolia, as well as parts of modern Syria during the second and third millennia B.C.E. They were once commonly known as Hittite hieroglyphs, as one of the first discovered uses of the script was on personal seals from the ancient Hittite capital, Hattusha. The language represented is Luwian (sometimes spelled “Luvian”,) not Hittite, and the term Luwian hieroglyphs is often used in English publications. It is possible that the hieroglyphs used on Hittite personal seals were used in a symbolic nature and were not intended to represent language, but rather concepts such as names, titles, or good luck symbols.[7]

Anatolian hieroglyphs utilize both logographic and phonographic elements, as well as the use of logographic elements that have a phonetic compliment. Most of the signs are pictorial in nature, representing human figures, plants, animals, and everyday objects. Text is most commonly arranged horizontally, beginning in a top corner and working its way down the page in alternating left-to-right/right-to-left registers. This practice was called boustrophedon by the Greeks, meaning "as the ox turns" (when plowing a field). Within each register, signs are arranged vertically in columns. There are no word breaks, although a word divider sign is sometimes found.[8]

Dongba script

The Dongba script is a pictographic writing system used by the priests of the Naxi people, an ethnic minority found mainly near the Yangtze River in China as well as in Tibet. The Dongba script is unique in that it is the only living pictographic language in the world; Naxi priests still use the Dongba script to create manuscripts for ceremonies like funerals and blessings.[9]

The origin of the Dongba script is a matter of legend and debate. It is likely that the script has been in use for close to 1,000 years, and was widely used by the tenth century. Both the Naxi language and script were suppressed after the Communist victory and during China’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, but efforts have been made to revive interest in the language.

The Dongba script consists of about 1,400 symbols. Ninety percent of these are pictograms, although some are used to represent phonetic values. The Naxi language is also written using Geba (a script more similar to Chinese character writing) or a Latin alphabet writing system based on Pinyin.[10]

|

|

Mayan hieroglyphs

The Mayan script, also known as Mayan hieroglyphs, was the writing system of the pre-Columbian Mayan civilization of Mesoamerica. It consisted of a highly elaborate set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls, or bark-paper codices, carved in wood or stone, or molded in stucco.

The Mayan script is made up of about 550 logograms (representing whole words), 150 syllabic glyphs (representing syllables), as well as glyphs for the names of places and gods. Thus, Mayan writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing.

For much of modern history, it was commonly believed that the Mayan script was not a complete writing system, and did not actually represent a language. In the 1950s, however, Russian ethnologist Yuri Knorozov suggested that the script was partly phonetic and represented the Yucatec Mayan language. The Yucatec Maya had actually used the script up until the sixteenth century. As a result of Knorozov's insight, many Mayan texts can now be interpreted.[10]

While the earliest known Mayan script is dated around 250 B.C.E., the script may have been developed much earlier. The Mayan civilization itself may have developed as early as 3000 B.C.E. Until recently it was thought that the Maya may have adopted writing from the Olmec or Epi-Olmec script.[11] Other related and nearby Mesoamerican cultures of the period were also heirs to the Olmec writing system, and developed parallel systems which shared key attributes (such as the base-twenty numerical system written with a system of bars and dots). However, it is generally believed that the Maya developed the only complete writing system in Mesoamerica, meaning that they were the only civilization that could write everything they could say.

Olmec hieroglyphs

The Olmec civilization was one of the first complex societies in early Mesoamerica, dating from 1500 B.C.E. through 100 B.C.E., and possibly even later. Although it was known that Olmec culture was full of accomplishments in art, mathematics, and engineering, including drainage systems and accurate calendars, it was not until the Cascajal Block was discovered in 1999 that there was any evidence of a true Olmec writing system.

The Cascajal Block was discovered by road builders in a pile of debris near Veracruz lowlands in the ancient Olmec heartland. The slab of rock is carved with 62 signs and dates to the early first millennium B.C.E. The block weighs approximately 26 pounds (12 kg), and is 36 centimeters (14 in) by 21 centimeters (8.3 in). The nature of the signs, their sequencing patterns, and consistent reading order are all indications that the tablet is an example of a Olmec writing system.

The symbols on the Cascajal block, some of which resemble plants, such as corn and ananas, or animals, such as insects and fish, are unlike those of any other writing system in Mesoamerica. The Cascajal block is also unusual because the symbols apparently run in horizontal rows and "there is no strong evidence of overall organization. The sequences appear to be conceived as independent units of information."[12] All other known Mesoamerican scripts typically use vertical rows.

Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing

Mí'kmaq hieroglyphic writing was used by the Mí'kmaq Native Americans, native to Nova Scotia and its surrounding areas.

The Mi’kmaq script primarily consists of a collection of ideograms. The Mi’kmaq had a rich oral tradition, and it has been suggested that hieroglyphs were used as either a memory aid or for trail marking. Since written language was not a major part of Mi’kmaq life, the ideograms eventually fell out of use, and were eventually replaced by phonetic versions of the Mi’kmaq language using the Latin alphabet.[13]

Father le Clercq, a Roman Catholic missionary on the Gaspé Peninsula, noted in 1691 that he had seen some Mí'kmaq children writing with charcoal symbols on birchbark while he taught them prayers. This and other accounts of writing that pre-date missionary visits serve to refute claims that the Mi’kmaq writing system was developed by missionaries as a way to teach Christian prayers. Missionaries worked to understand and develop the writing system into a fully functional written language in order to translate prayers like The Lord’s Prayer, adding new ideograms to refer to concepts like God (a triangle to represent the trinity.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Jim Loy, Types of Signs in Egyptian, Jim Loy's Egyptian Hieroglyphics and Egyptology Page, 2002. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Bob Brier, Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians (Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 0313303134), 202.

- ↑ Francesca Jourdan, "The Narmer Palette," InScription, Journal of Ancient Egypt (7) (2000). Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian; A Linguistic Introduction (Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0521448492), 12.

- ↑ Arthur J. Evans, "Writing in Prehistoric Greece," The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 30 (1900): 91-93.

- ↑ Athena Publications, "Bronze Age Writing on Crete: Hieroglyphs, Linear A, and Linear B," Athena Review 3(3) (2003):21. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, The World’s Writing Systems (Oxford University Press, 1996), 120. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, The World’s Writing Systems (Oxford University Press, 1996), 121-123. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Mi Chu Wiens, "Living Pictographs:Asian Scholar Unlocks Secrets of the Naxi Manuscripts," Library of Congress Information Bulletin 58(6) (June 1999). Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Simon Ager, "Naxi Scripts," Omniglot, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Linda Schele and David Friedel, A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (New York, NY: William Morrow, 1990, ISBN 0688074561).

- ↑ Joel Skidmore, "The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing," Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "About Mi’Kmaw 'Hieroglyphics'," Mi’kmaq Spirit, 2007. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Betro, Maria C. Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt Abbeville Press, 1996. ISBN 0789202328

- Harris, John F. and Stephen K. Stearns. Understanding Maya Inscriptions: A Hieroglyph Handbook, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1997. ISBN 0924171413

- Loprieno, Antonio. Ancient Egyptian; A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0521448492

- Mercer, Samuel and Janice Kamrin. The Handbook of Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Study of the Ancient Language. Hippocrane Books, 1998. ISBN 0781806259

- Pool, Christopher. Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0521783127

- Robinson, Andrew. The story of writing with over 350 illustrations, 50 in color. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500281564

- Schele, Linda, and David Friedel. A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York, NY: William Morrow, 1990. ISBN 0688074561

- Schmidt, David L., and Murdena Marshall. 1995. Míkmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America's First Indigenous Script. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 1551090694

- Skidmore, Joel. "The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing," Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- Stawell, F. Melian. Clue to the Cretan Scripts. Kessinger Publishing, LLC., 2003. ISBN 0766128415

- Wilford, John Noble. "3,000-year-old script on stone found in Mexico," San Francisco Chronicle, September 15, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- Woodard, Roger D. The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press, 2008. ISBN 052168496X

External links

All links retrieved December 24, 2017.

- The Cretan Hieroglyphic Texts

- Luwian

- Analysis of Olmec Hieroglyphs

- Micmac at ChristusRex.org – A large collection of scans of prayers in Míkmaq hieroglyphs.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Hieroglyph history

- Cursive_hieroglyphs history

- Dongba_script history

- Cretan_hieroglyphs history

- Anatolian_hieroglyphs history

- Maya_script history

- Cascajal_Block history

- Isthmian_script history

- Mi'kmaq_hieroglyphic_writing history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.