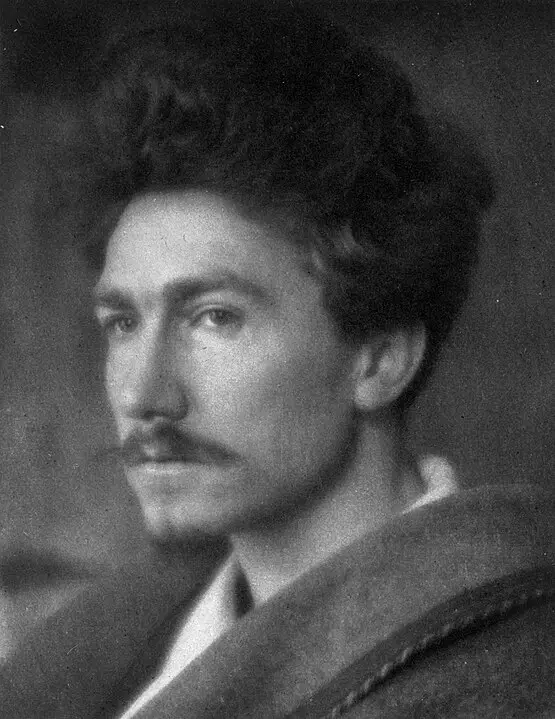

Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (October 30 1885 – November 1 1972) was an American expatriate, poet, musician and critic who, along with T. S. Eliot, was a major figure of the modernist movement in early 20th century poetry. He combined a vast knowledge of existing European traditions with an eye modern experimentalism. Although he is rarely considered the greatest poet of the modern period, he is almost unanimously believed to be the most important teacher and catalyst among the writers and artists of his time.

Early life and contemporaries

Pound was born in Hailey, Idaho, United States. He studied for two years at the University of Pennsylvania and later received his B.A. from Hamilton College in 1905. During studies at Penn, he met and befriended William Carlos Williams, and H.D., to whom he was engaged for a time. He taught at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana for less than a year, and left as the result of a minor scandal. In 1908 he traveled to Europe, settling in London after spending several months in Venice.

Pound and Yeats

Pound's early poetry was inspired by his reading of the pre-Raphaelites and other 19th century poets, as well as medieval Romance literature. He was also deeply influenced by neo-Romanticism and occult/mystical philosophy. When he moved to London, under the influence of Ford Madox Ford and T. E. Hulme, he began to cast off archaic, overtly poetic language and forms in an attempt to remake himself as a poet. He believed W. B. Yeats was the greatest living poet of his time, and befriended him in England, eventually being employed as his secretary.

During this time, Yeats and Pound were instrumental in helping each other modernise English poesy. The two writers lived together at Stone Cottage in Sussex, England, studying Japanese, especially Noh plays. They paid particular attention to the works of Ernest Fenollosa, an American professor in Japan, whose work on Chinese characters was developed by Pound into what he called the Ideogrammic Method.

The Ideogrammic Method

The Ideogrammic Method was a technique expounded by Pound which allowed poetry to deal with abstract content through concrete images. The idea was based on Pound's reading of the work of Fenollosa, and in particular his notes on the Chinese ideogram.

Pound gives a brief account of the idea in his instructional booklet The ABC of Reading. He explains his admiration for the way abstract Chinese characters were formed by drawing pictures of concrete things. He uses the example of the character for 'dawn' (a word which in a non-ideogrammatic language like English is almost always as metaphorical as it is literal.) In Chinese, 'dawn' is represented by the superposition of the characters for 'tree' and 'sun'; that is, a picture of the sun tangled in a tree's branches. Pound found this compression of complex thought through images to be an incredibly useful tool for poets. He suggested how, with such a system, the concept of 'red' might be presented by putting together the pictures of:

| ROSE | CHERRY |

| IRON RUST | FLAMINGO |

This was a key idea in the development of Imagism, because, according to Pound, it allowed for poets to communicate about abstractions and generalities (even something as general as the color red) without losing touch with the real world and the things in it.

Imagism

In the years before the First World War, Pound was largely responsible for the appearance of Imagism and Vorticism, philosophies and art and poetics deeply rooted in the ideogrammatic method he had developed through his study of Chinese and Japanese forms. These two movements, which helped bring to notice the work of poets and artists like James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, William Carlos Williams, H.D., Richard Aldington, Marianne Moore, Rebecca West and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, can be seen as perhaps the central events in the birth of English-language modernism. Pound also edited his friend Eliot's The Waste Land, the poem that was to force the new poetic sensibility into broader public attention.

The war, however, shattered Pound's belief in modern western civilization and he abandoned London soon after for Italy, but not before he published Homage to Sextus Propertius (1919) and Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920). If these poems together form a farewell to Pound's London career, The Cantos, which he began in 1915, pointed his way forward.

In Italy, Pound continued to act as a patron and catalyst to numerous artists. The young sculptor Heinz Henghes came to see Pound, arriving penniless. He was given lodging and marble to carve, and quickly learned to work in stone. The poet James Laughlin, who lodged with Pound, was also inspired at this time to start the publishing company New Directions which would become a vehicle for many new authors. Pound also organised an annual series of concerts in Rapallo where a wide range of classical and contemporary music was performed. In particular this musical activity contributed to the 20th century revival of interest in Vivaldi, who had been neglected since his death. Throughout all of this, Pound continued to work incessantly on The Cantos, an epic poem which would eventually become far and away the poet's most important work, and one of the longest and most influential poems in the English language.

The Cantos

The Cantos consist of a long, incomplete poem in 120 sections. Each of these sections is referred to as a canto, Italian for song. Most of the cantos were written between 1915 and 1962, although much of the early work was abandoned and the early cantos, as finally published, date from 1922 onwards. It is a book-length work, and is widely considered to be one of the most formidable poems in the English language. Strong claims have been made for it as one of the most significant works of poetry in the twentieth century. The poem is, in essence, a sustained philosophical investigation, with particular attention to the themes of economics, governance, and culture and their relation to the creative activity of the poet.

The difficulty of the poem is apparent even to a casual browser; a cursory reader will notice that the poem includes Chinese characters as well as lengthy quotations in European languages other than English. Recourse to scholarly commentaries is almost inevitable for any reader. The range of allusion to historical events is very broad in both time and place: Pound added to his earlier interests in the ancient cultures of the Mediterranean and East Asia by selecting topics ranging from medieval and early modern Italy and Provence to the beginnings of the United States, the state of England in the seventeenth century, and details from African cultures he had obtained from Leo Frobenius. References left without explanation abound.

Structure

As it lacks any plot or definite ending, The Cantos can appear on first reading to be chaotic or structureless. One early critic, R.P. Blackmur, wrote, in his 1934 essay Masks of Ezra Pound (reprinted in Sullivan) "The work of Ezra Pound has been for most people almost as difficult to understand as Soviet Russia; The Cantos are not complex, they are complicated". The issue of incoherence of the work is reflected in the equivocal note sounded in the final two more-or-less completed cantos; according to the William Cookson guide (p.264), they show that Pound has been unable to make his materials cohere, while they insist that the world itself still does cohere.

Nevertheless, there are indications in Pound's other writings that there may have been some formal plan underlying the work. In his 1918 essay A Retrospect, Pound wrote "I think there is a 'fluid' as well as a 'solid' content, that some poems may have form as a tree has form, some as water poured into a vase. That most symmetrical forms have certain uses. That a vast number of subjects cannot be precisely, and therefore not properly rendered in symmetrical forms". Critics like Hugh Kenner who take a more positive view of The Cantos have tended to follow this hint, seeing the poem as a poetic record of Pound's life that sends out new branches as new needs arise, like a tree, displaying a kind of unpredictable inevitability.

Another approach to the structure of the work is based on a letter Pound wrote to his father in the 1920s, in which he stated that his plan was:

- A. A. Live man goes down into world of dead.

- C. B. 'The repeat in history.'

- B. C. The 'magic moment' or moment of metamorphosis, bust through from quotidian into 'divine or permanent world.' Gods, etc.

The poem's symbolic structure also makes use of an opposition between darkness and light. Images of light are used variously, and may represent neoplatonic ideas of divinity, the artistic impulse, love (both sacred and physical) and good governance, amongst other things. The moon is frequently associated in the poem with creativity, while the sun is more often found in relation to the sphere of political and social activity, although there is frequent overlap between the two. From the Rock Drill sequence on, the poem's effort is to merge these two aspects of light into a unified whole.

The Cantos was initially published in the form of separate sections, each containing several cantos that were numbered sequentially using Roman numerals. The original publication dates for the groups of cantos are as given below. The complete collection of cantos was published together in 1987 (including a final short coda or fragment, dated 24 August 1966).

I – XVI

The first canto begins with Pound's translation of a Latin version of Homer's Odyssey by the Renaissance scholar Andreas Divus. Using the meter and syntax of his 1911 version of the Anglo-Saxon poem The Seafarer, Pound made an English version of Divus' rendering of the Nekuia episode in which Odysseus and his companions sail to Hades in order to find out what their future holds. In using this passage to open the poem, Pound introduces a major theme: the excavating of the 'dead' past to illuminate both present and future. He also echoes Dante's opening to The Divine Comedy in which the poet also descends into hell to interrogate the dead. The canto concludes with some fragments from the Second Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, in a Latin version by Georgius Dartona which Pound found in the Divus volume, followed by "So that:", an invitation to read on.

Cantos VIII - XI draw on the story of Sigismondo Malatesta, quattrocento poet, soldier, lord of Rimini and patron of the arts. Quoting extensively from primary sources, including Malatesta's letters, Pound especially focuses on the building of the church of San Francesco, also known as the Tempio Malatestiano. Designed by Leon Battista Alberti and decorated by artists including Piero della Francesca and Agostino di Duccio, this was a landmark Renaissance building, being the first church to use the Roman triumphal arch as part of its structure. For Pound, who spent a good deal of time seeking patrons for himself, Joyce, Eliot and a string of little magazines and small presses, the role of the patron was a crucial cultural question, and Malatesta is the first in a line of ruler-patrons to appear in The Cantos.

The remainder of this section of The Cantos concludes with a vision of capitalism and Hell. Cantos XIV and XV use the convention of the Divine Comedy to present Pound/Dante moving through a hell populated by bankers, newspaper editors, hack writers and other 'perverters of language' and the social order. In Canto XV, Plotinus takes the role of guide played by Virgil in Dante's poem. These visions are followed by a transcript of Lincoln Steffens' account of the Russian Revolution. These two events, the war and revolution, mark a decisive break with the historic past, including the early modernist period when these writers and artists formed a more-or-less coherent movement.

XVII – XXX

Originally, Pound conceived of Cantos XVII - XXVII as a group that would follow the first volume by starting with the Renaissance and ending with the Russian Revolution. He then added a further three cantos and the whole eventually appeared as A Draft of XXX Cantos in an edition of 200 copies. The major locus of these cantos is the city of Venice, and are concerned with the formation of banking and the rise of social decay, a trend which Pound calls 'usury', in medieval Europe.

XXXI – XLI (XI New Cantos)

- Published as Eleven New Cantos XXXI-XLI. New York: Farrar & Rinehart Inc., 1934.

The first four cantos of this volume (Cantos XXXI - XXXVI) use extensive quotations from the letters and other writings of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren and others to deal with the emergence of the fledgling United States and, particularly, the American banking system.

XLII – LI (Fifth Decad, called also Leopoldine Cantos)

- Published as The Fifth Decad of the Cantos XLII-LI. London: Faber & Fber, 1937.

Cantos XLII, XLIII and XLIV move to the Sienese bank of the Monte dei Paschi. Under the rule of the Arch Duke Pietro Leopoldo it represents for Pound a non-capitalist ideal. Canto XLV is a litany against Usura or usury, which Pound defines as a charge on credit regardless of potential or actual production and the creation of wealth ex nihilo by a bank to the benefit of its shareholders. Canto XLVI contrasts what has gone before with the practices of institutions such as the Bank of England that are designed to exploit the issuing of credit to make profits.

The poem returns to the island of Circe and Odysseus about to "sail after knowledge" in Canto XLVII. There follows a long lyrical passage in which a ritual of floating votive candles on the bay at Rapallo near Pound's home merges with the cognate myths of Tammuz and Adonis, agricultural activity set in a calendar based on natural cycles, and fertility rituals.

Canto XLVIII presents more instances of what Pound considers to be usury. The canto then moves via Montsegur to the village of St-Bertrand-de-Comminges. Canto XIL is a poem of tranquil nature derived from a Chinese picturebook. Canto L, which again contains anti-Semitic statements, moves from John Adams to the failure of the Medici bank. The final canto in this sequence returns to the usura litany of Canto XLV, followed by detailed instructions on making flies for fishing, and ends with the first Chinese written characters to appear in the poem, representing the Rectification of Names from the Analects of Confucius

LII – LXI (The China Cantos)

- First published in Cantos LII-LXXI. Norfolk Conn.: New Directions, 1940.

These eleven cantos are based on the first eleven volumes of the twelve-volume Histoire generale de la Chine by Joseph-Anna-Marie de Moyriac de Mailla (volume 12 being an index). De Mailla was a French Jesuit who spent 37 years in Peking and wrote his history there. The work was completed in 1730 but not published until 1777-1783. De Mailla was very much an Enlightenment figure and his view of Chinese history reflects this. He found Confucian political philosophy, with its emphasis on rational order, very much to his liking. He also disliked what he saw as the superstitious pseudo-mysticism promulgated by both Buddhists and Taoists, to the detriment of rational politics. Pound, in turn, fitted de Mailla's take on China into his own views on Christianity, the need for strong leadership to address 20th-century fiscal and cultural problems and his support of Mussolini.

LXII – LXXI (The Adams Cantos)

- First published in Cantos LII-LXXI. Norfolk Conn.: New Directions, 1940.

This section of the cantos is, for the most part, made up of fragmentary citations from the writings of John Adams. Pound's intentions appear to be to show Adams as an example of the rational Enlightenment leader, thereby continuing the primary theme of the preceding China Cantos sequence which these cantos also follow from chronologically. Adams is depicted as a rounded figure; he is a strong leader with interests in political, legal and cultural matters in much the same way that Malatesta and Mussolini are portrayed elsewhere in the poem.

LXXII – LXXIII

- Written between 1940 and 1944.

These two cantos, written in Italian, were not published until their posthumous inclusion in the 1987 revision of the complete text of the poem. They cover much familiar ground; Sigismondo, Dante and Cavalcanti appear, as does Pound's linking of usury and Jews in another anti-Semitic rant aimed at Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden. In contrast with some of his earlier critical writings, Pound praises the Futurist writer Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

LXXIV – LXXXIV (The Pisan Cantos)

- First published as The Pisan Cantos. New York: New Directions, 1948.

Pound was arrested by Italian partisans in April 1945 and was eventually transferred to the American Disciplinary Training Center (DTC) on May 22. Here he was held in a specially reinforced cage, initially sleeping on the ground in the open air. After some time he was given a cot and pup tent. After three months, he had a breakdown that resulted in his being moved to the medical compound. Here, he gained access to a typewriter. For reading matter, he had a regulation-issue Bible along with three books he was allowed to bring in as his own "religious" texts: a Chinese text of Confucius, James Legge's translation of the same, and a Chinese dictionary. The only other thing he brought with him was a eucalyptus pipe. Throughout the Pisan sequence, Pound repeatedly likens the camp to Francesco del Cossa's March fresco depicting men working at a grape arbour.

The Rock-Drill Section: LXXXV – XCV

- Published in 1956 as Section: Rock-Drill, 85-95 de los cantares by New Directions, New York.

Pound was flown from Pisa to Washington to face trial on a charge of treason in 1946. Found unfit to stand trial because of the state of his mental health, he was incarcerated in St. Elizabeth's Hospital, where he was to remain until 1958. Here he began to entertain writers and academics with an interest in his work and to write, working on translations of the Confucian Book of Odes and of Sophocles' play the Women of Trachis as well as two new sections of the cantos; the first of these was Rock Drill.

The two main written sources for the Rock Drill cantos are the Confucian Classic of History, in an edition by the French Jesuit Séraphin Couvreur, which contained the Chinese text and translations into Latin and French under the title Chou King (which Pound uses in the poem), and Senator Thomas Hart Benton's Thirty Years View: Or A History of the American Government for Thirty Years From 1820-1850, which covers the period of the bank wars. In as interview given in 1962, and reprinted by J.P Sullivan (see References), Pound said that the title Rock Drill "was intended to imply the necessary resistance in getting a main thesis across — hammering."

XCVI – CIX (Thrones)

Thrones was the second volume of cantos written while Pound was incarcerated in St. Elizabeth's. In the same 1962 interview, Pound said of this section of the poem: "The thrones in Dante's Paradiso are for the spirits of the people who have been responsible for good government. The thrones in The Cantos are an attempt to move out from egoism and to establish some definition of an order possible or at any rate conceivable on earth… Thrones concerns the states of mind of people responsible for something more than their personal conduct."

Drafts and fragments of Cantos CX - CXVII

- First published as Drafts and Fragments of Cantos CX - CXVII. New York: New Directions, 1969.

In 1958, Pound was declared incurably insane and permanently incapable of standing trial. Consequent on this, he was released from St Elizabeth's on condition that he return to Europe, which he promptly did. At first, he lived with his daughter Mary in the Tyrol, but soon returned to Rapallo. A crisis of belief (In November 1959, Pound wrote to his publisher James Laughlin that he "has forgotten what or which politics he ever had. Certainly has none now."), together with the effects of aging meant that the proposed paradise cantos were slow in coming and turned out to be radically different to anything the poet had envisaged.

Pound was reluctant to publish these late cantos, but the appearance in 1967 of a pirate edition of Cantos 110-116 forced his hand. Laughlin pushed Pound to publish an authorised edition, and the poet responded by supplying the more-or-less abandoned drafts and fragments he had, plus two fragments dating from 1941. The resulting book, therefore, can hardly be described as representing Pound's definitive planned ending to the poem. This situation has been further complicated by the addition of more fragments in editions of the complete poem published after the poet's death. One of these was titled Canto CXX at one point, on no particular authority. This title was later removed.

Although some of Pound's intention to "write a paradise" survives in the text as we have it, especially in images of light and of the natural world, other themes also intruded. These include the poet's coming to terms with a sense of artistic failure, and jealousies and hatreds that must be faced and expiated.

The last canto completed by Pound opens with a passage in which we see the Odysseus/Pound figure's homecoming achieved. However, the home achieved is not the place intended when the poem was begun but is the terzo cielo ("third heaven") of human love. The canto contains the following well-known lines:

- I have brought the great ball of crystal;

- Who can lift it?

- Can you enter the great acorn of light?

- But the beauty is not the madness

- Tho' my errors and wrecks lie about me.

- And I am not a demigod,

- I cannot make it cohere.

This passage has often been taken as an admission of failure on Pound's part, but the reality may be more complex. The crystal image relates back to the Sacred Edict on self-knowledge and the demigod/cohere lines relate directly to Pound's translation of the Women of Trachis. In this, the demigod Herakles cries out "WHAT SPLENDOUR/IT ALL COHERES" as he is dying. These lines read in conjunction with the later "i.e. it coheres all right/even if my notes do not cohere" point towards the conclusion that towards the end of his effort, Pound was coming to accept not only his own "errors" and "madness" but the conclusion that it was beyond him, and possibly beyond poetry, to do justice to the coherence of the universe. Images of light that saturate this canto, culminating in the closing lines: "A little light, like a rushlight / to lead back to splendour". These lines again echo the Noh of Kakitsubata, the "light that does not lead on to darkness" in Pound's version.

Legacy

Despite all the controversy surrounding both poem and poet, The Cantos has been influential in the development of English-language long poems since the appearance of the early sections during the 1920s. Amongst poets of Pound's own generation, both H.D. and William Carlos Williams wrote long poems that show this influence.

Almost all of H.D.'s poetry from 1940 onwards takes the form of long sequences, and her Helen in Egypt, written during the 1950s, covers much of the same Homeric ground as The Cantos, but from a feminist perspective. In the case of Williams, his Paterson (1963) follows Pound in using incidents and documents from the early history of the United States as part of its material. As with Pound, Williams includes Alexander Hamilton as the villain of the piece.

Pound was a major influence on the Objectivist poets, and the impact of The Cantos on Zukofsky's "A" is clearly noticeable. The other major long work by an Objectivist, Charles Reznikoff's Testimony, (1934 – 1978) follows Pound in the direct use of primary source documents as its raw material. In the next generation of American poets, Charles Olson also drew on Pound's example in writing his own unfinished Modernist epic The Maximus Poems.

Pound was also an important figure for the poets of the Beat generation, especially Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg. Snyder's interest in things Chinese and Japanese stemmed from his early reading of Pound's writings and his long poem Mountains and Rivers Without End (1965 – 1996) reflects his reading of The Cantos in many of the formal devices used. In Ginsberg's development, reading Pound was influential in his move away from the long, Whitmanesque lines of his early poetry, including towards the more varied metric and inclusive approach to a variety of subjects in the single poem that is to be found especially in his book-length sequences Planet News (1968) and The Fall of America: Poems of These States (1973).

More generally, The Cantos, with its wide range of references and inclusion of primary sources including prose texts can be seen as prefiguring found poetry. Pound's tacit insistence that this material becomes poetry because of his action in including it in a text he chose to call a poem also prefigures the attitudes and practices that underlie 20th-century Conceptual art.

Pound's Institutionalization and Decline

After the war, Pound was brought back to the United States to face charges of treason relating to his work as a radio broadcaster for Italy during the war. He was found unfit to face trial because of insanity and sent to St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he remained for 12 years from 1946 to 1958. Following his release, he was sent back to Italy, where he remained until his death in 1972.

At St. Elizabeths, Pound was surrounded by poets and other admirers and continued working on The Cantos as well as translating the Confucian classics. Many of the poets and artists who visited Pound would probably have been horrified to learn that another of his most frequent visitors was the then-chairman of the States' Rights Democratic Party, with whom Pound used to discuss strategy and tactics on how best to rally public support for the preservation of racial segregation in the American South.

Pound was finally released after a concerted campaign by many of his fellow poets and artists, particularly Robert Frost. He was still considered incurably insane, but not dangerous to others. On his release, Pound returned to Italy where he continued writing, but his old certainties had deserted him. Although he continued working on The Cantos, he seemed to view them as an artistic failure. He also seemed to regret many of his past actions, and in a 1967 interview with Allen Ginsberg he apologised for "that stupid, suburban prejudice of anti-Semitism", although contemporaneous letters published in recent years indicate that he was still unrepentently anti-semitic. He died in Venice in 1972.

Pound's Importance

Because of his political views, especially his support of Mussolini and his anti-Semitism, Pound continues to attract much criticism. While it is almost impossible to ignore the vital role he played in the modernist revolution in 20th century literature in English, Pound's perceived importance has varied over the years. The location of Pound — as opposed to other writers such as T.S. Eliot — at the center of the Anglo-American Modernist tradition was famously asserted by the critic Hugh Kenner, most fully in his account of the Modernist movement titled The Pound Era. The critic Marjorie Perloff has also insisted upon the centrality of Pound to numerous traditions of "experimental" poetry in the 20th century.

As a poet, Pound was one of the first to successfully employ free verse in extended compositions. Almost every 'experimental' poet in English since the early 20th century has been considered by some to be in his debt.

As a critic, editor and promoter, Pound helped the careers of Yeats, Eliot, Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams, H.D., Marianne Moore, Ernest Hemingway, D. H. Lawrence, Louis Zukofsky, Basil Bunting, George Oppen, Charles Olson and other modernist writers too numerous to mention as well as neglected earlier writers like Walter Savage Landor and Gavin Douglas.

As a translator, although his mastery of languages is open to question, Pound did much to introduce Provençal and Chinese poetry, the Noh, Anglo-Saxon poetry and the Confucian classics to a Western audience. He also translated and championed Greek and Latin classics and helped keep these alive for poets at a time when classical education was in decline.

In the early 1920s in Paris, Pound became interested in music, and was probably the first serious writer in the 20th century to praise the work of the long-neglected Italian composer Antonio Vivaldi and to promote early music generally. He also helped the early career of George Antheil, and collaborated with him on various projects.

The secret to Pound's seemingly bizarre theories and political commitments perhaps lie in his occult and mystical interests, which biographers have only recently begun to document. 'The Birth of Modernism' by Leon Surette is perhaps the best introduction to this aspect of Pound's thought.

Selected works

- 1908 A Lume Spento, poems.

- 1908 A Quinzaine for This Yule, poems.

- 1909 Personae, poems.

- 1909 Exultations, poems.

- 1910 Provenca, poems.

- 1910 The Spirit of Romance, essays.

- 1911 Canzoni, poems.

- 1912 Ripostes of Ezra Pound, poems.

- 1912 Sonnets and ballate of Guido Cavalcanti, translations.

- 1915 Cathay, poems / translations.

- 1916 Certain noble plays of Japan: from the manuscripts of Ernest Fenollosa, chosen and finished by Ezra Pound, with an introduction by William Butler Yeats.

- 1916 "Noh", or, Accomplishment: a study of the classical stage of Japan, by Ernest Fenollosa and Ezra Pound.

- 1917 Lustra of Ezra Pound, poems.

- 1917 Twelve Dialogues of Fontenelle, translations.

- 1918 Quia Pauper Amavi, poems.

- 1918 Pavannes and Divisions, essays.

- 1919 The Fourth Canto, poems.

- 1920 Umbra, poems and translations.

- 1920 Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, poems.

- 1921 Poems, 1918-1921, poems.

- 1922 The Natural Philosophy of Love, by Rémy de Gourmont, translations.

- 1923 Indiscretions, essays.

- 1924 Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony, essays.

- 1925 A Draft of XVI Cantos, poems.

- 1927 Exile, poems

- 1928 A Draft of the Cantos 17-27, poems.

- 1928 Ta hio, the great learning, newly rendered into the American language, translation.

- 1930 Imaginary Letters, essays.

- 1931 How to Read, essays.

- 1933 A Draft of XXX Cantos, poems.

- 1933 ABC of Economics, essays.

- 1934 Homage to Sextus Propertius, poems.

- 1934 Eleven New Cantos: XXXI-XLI, poems.

- 1934 ABC of Reading, essays.

- 1935 Make It New, essays.

- 1936 Chinese written character as a medium for poetry, by Ernest Fenollosa, edited and with a foreword and notes by Ezra Pound.

- 1936 Jefferson and/or Mussolini, essays.

- 1937 The Fifth Decade of Cantos, poems.

- 1937 Polite Essays, essays.

- 1937 Digest of the Analects, by Confucius, translation.

- 1938 Culture, essays.

- 1939 What Is Money For?, essays.

- 1940 Cantos LII-LXXI, poems.

- 1944 L'America, Roosevelt e le Cause della Guerra Presente, essays.

- 1944 Introduzione alla Natura Economica degli S.U.A., prose.

- 1947 Confucius: the Unwobbling pivot & the Great digest, translation.

- 1948 The Pisan Cantos, poems.

- 1950 Seventy Cantos, poems.

- 1951 Confucian analects, translated by Ezra Pound.

- 1956 Section Rock-Drill, 85-95 de los Cantares, poems.

- 1956 Women of Trachis, by Sophocles, translation.

- 1959 Thrones: 96-109 de los Cantares, poems.

- 1968 Drafts and Fragments: Cantos CX-CXVII, poems.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1988). A Serious Character: The Life of Ezra Pound. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Kenner, Hugh (1973). The Pound Era. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bacigalupo, Massimo (1980). The Forméd Trace: The Later Poetry of Ezra Pound. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Longenbach, James (1991). Stone Cottage: Pound, Yeats and Modernism. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oderman, Kevin (1986). Ezra Pound and the Erotic Medium. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

- Redman, Tim (1991). Ezra Pound and Italian Fascism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stock, Noel (1970). Life of Ezra Pound. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

- Surette, Leon (1994). The Birth of Modernism: Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats, and the Occult. McGill-Queen's University Press.

External links

- Pound at Modern American Poetry

- Pound at EPC

- Pound and the Occult

- Fenollosa, Pound and the Chinese Character

- A collection of Pound's poetry

- Works by Ezra Pound. Project Gutenberg

- Ezra Pound: His Metric and Poetry, available for free via Project Gutenberg, by T. S. Eliot

Audio recordings

- Recording of "Usura" Canto XLV, read by Pound (mp3).

- Recording of sections from Hugh Selwyn Mauberley and others, read by Pound (RealAudio).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.