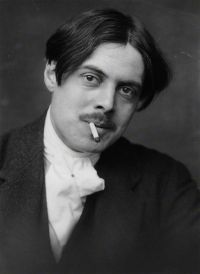

Wyndham Lewis

Percy Wyndham Lewis (November 18, 1882 – March 7, 1957) was a Canadian-born British painter and author. He was a co-founder of the Vorticist movement in art, and edited the Vorticists' journal, BLAST (two numbers, 1914-15). Vorticism was a short lived British art movement of the early twentieth century. It is considered to be the only significant British movement of the early twentieth century, but lasted less than three years.[1]

The name Vorticism was given to the movement by Ezra Pound in 1913, although Lewis, usually seen as the central figure in the movement, had been producing paintings in the same style for a year or so previously.[2]

The journal, BLAST, contained work by Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, as well as by the Vorticists themselves. Its typographical adventurousness was cited by El Lissitzky as one of the major forerunners of the revolution in graphic design in the 1920s and 1930s.

His novels include his pre-World War I era novel, Tarr (set in Paris), and The Human Age, a trilogy comprising The Childermass (1928), Monstre Gai, and Malign Fiesta (both 1955), set in the afterworld. A fourth volume of The Human Age, The Trial of Man, was begun by Lewis but left in a fragmentary state at the time of his death.

Biography

Early life

Lewis was born on his father's yacht off the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.[3] His British mother and American father separated about 1893. His mother subsequently returned to England, where Lewis was educated, first at Rugby School, then at the Slade School of Art in London, before spending most of the 1900s traveling around Europe and studying art in Paris.

Early career and Vorticism

Mainly residing in England from 1908, Lewis published his first work (accounts of his travels in Brittany) in Ford Madox Ford's The English Review in 1909. He was an unlikely founder-member of the Camden Town Group in 1911. In 1912 he exhibited his Cubo-Futurist illustrations to Timon of Athens (later issued as a portfolio, the proposed edition of William Shakespeare's play never materializing) and three major oil-paintings at the second Post-Impressionist exhibition. This brought him into close contact with the Bloomsbury Group, particularly Roger Fry and Clive Bell, with whom he soon fell out.

In 1912, he was commissioned to produce a decorative mural, a drop curtain, and more designs for The Cave of Golden Calf, an avant-garde cabaret and nightclub on London's Heddon Street.[4]

It was in the years 1913-15, that he found the style of geometric abstraction for which he is best known today, a style which his friend Ezra Pound dubbed "Vorticism." Lewis found the strong structure of Cubist painting appealing, but said it did not seem "alive" compared to Futurist art, which, conversely, lacked structure. Vorticism combined the two movements in a strikingly dramatic critique of modernity. In a Vorticist painting, modern life is shown as an array of bold lines and harsh colors, drawing the viewer's eye into the center of the canvas.

In his early works, particularly versions of village life in Brittany, showing dancers (c. 1910-12), Lewis may have been influenced by the process philosophy of Henri Bergson, whose lectures he attended in Paris. Though he was later savagely critical of Bergson, he admitted in a letter to Theodore Weiss (dated April 19, 1949) that he "began by embracing his evolutionary system." Friedrich Nietzsche was an equally important influence.

After a brief tenure at the Omega Workshops, Lewis disagreed with the founder, Roger Fry, and left with several Omega artists to start a competing workshop called the Rebel Art Center. The Center operated for only four months, but it gave birth to the Vorticism group and the publication, BLAST.[5] In BLAST, Lewis wrote the group's manifesto, contributed art, and wrote articles.

World War I: Artillery officer and war artist

After the Vorticists' only exhibition in 1915, the movement broke up, largely as a result of World War I. Lewis was posted to the western front, and served as a second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery. After the Battle of Ypres in 1917, he was appointed as an official war artist for both the Canadian and British governments, beginning work in December 1917.

For the Canadians he painted A Canadian Gun-Pit (1918, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa) from sketches made on Vimy Ridge. For the British, he painted one of his best known works, A Battery Shelled (1919, Imperial War Museum), drawing on his own experience in charge of a 6-inch howitzer at Passchendaele. Lewis exhibited his war drawings and some other paintings of the war in an exhibition, Guns, in 1918.

His first novel, Tarr, was also published as a single volume in 1918, after it had been serialized in The Egoist during 1916-17. It is widely regarded as one of the key modernist texts. Lewis later documented his experiences and opinions of this period of his life in the autobiographical Blasting and Bombardiering (1937), which also covered his post-war art.

The 1920s: Modernist painter and The Enemy

After the war, Lewis resumed his career as a painter, with a major exhibition, Tyros and Portraits, at the Leicester Galleries in 1921. "Tyros" were satirical caricature figures intended by Lewis to comment on the culture of the "new epoch" that succeeded the First World War. A Reading of Ovid and Mr Wyndham Lewis as a Tyro are the only surviving oil paintings from this series. As part of the same project, Lewis also launched his second magazine, The Tyro, of which there were only two issues. The second (1922) contained an important statement of Lewis's visual aesthetic: "An Essay on the Objective of Plastic Art in our Time."[6] It was during the early 1920s that he perfected his incisive draughtsmanship.

By the late 1920s, he cut back on his painting, instead concentrating on his writing. He launched yet another magazine, The Enemy (three issues, 1927-29), largely written by himself and declaring its belligerent critical stance in its title. The magazine, and the theoretical and critical works he published between 1926 and 1929, mark his deliberate separation from the avant-garde and his previous associates. Their work, he believed, failed to show sufficient critical awareness of those ideologies that worked against truly revolutionary change in the West. As a result, their work became a vehicle for these pernicious ideologies. His major theoretical and cultural statement from this period is The Art of Being Ruled (1926). Time and Western Man (1927) is a cultural and philosophical discussion that includes penetrating critiques of James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound that are still read. Philosophically, Lewis attacked the "time philosophy" (that is, process philosophy) of Bergson, Samuel Alexander, Alfred North Whitehead, and others.

The 1930s

Politics and fiction

In The Apes of God (1930), Lewis wrote a biting satirical attack on the London literary scene, including a long chapter caricaturing the Sitwell family, which did not help his position in the literary world. His book, Hitler (1931), which presented Adolf Hitler as a "man of peace" whose party members were threatened by communist street violence, confirmed his unpopularity among liberals and anti-fascists, especially after Hitler came to power in 1933. He later wrote The Hitler Cult (1939), a book which firmly revoked his earlier willingness to entertain Hitler, but politically, Lewis remained an isolated figure in the 1930s. In Letter to Lord Byron, Auden called him "that lonely old volcano of the Right." Lewis thought there was what he called a "left-wing orthodoxy" in Britain in the '30s. He believed it was not in Britain's interest to ally itself with Soviet Russia, "which the newspapers most of us read tell us has slaughtered out-of-hand, only a few years ago, millions of its better fed citizens, as well as its whole imperial family" (Time and Tide, March 2, 1935, p. 306).

Lewis's novels are known among some critics for their satirical and hostile portrayals of Jews and other minorities, as well as homosexuals. The 1918 novel, Tarr, was revised and republished in 1928. In an expanded incident, a new Jewish character is given a key role in making sure a duel is fought. This has been interpreted as an allegorical representation of a supposed Zionist conspiracy against the West.[7] The Apes of God (1930) has been interpreted similarly, because many of the characters satirized are Jewish, including the modernist author and editor, Julius Ratner, a portrait which blends antisemitic stereotype with historical literary figures (John Rodker and James Joyce, though the Joyce element consists solely in the use of the word "epiphany" in the parody of Rodker Lewis includes).

A key feature of these interpretations is that Lewis is held to have kept his conspiracy theories hidden and marginalized. Since the publication of Anthony Julius's T. S. Eliot, Anti-Semitism, and Literary Form (1995, revised 2003), in which Lewis's antisemitism is described as "essentially trivial," this view is no longer taken seriously. Still, when he somewhat belatedly recognized the reality of Nazi treatment of Jews after a visit to Berlin in 1937, he wrote an attack on antisemitism: The Jews, Are They Human? (published early in 1939; the title is modeled on a contemporary bestseller, The English, Are They Human?). The book was favorably reviewed in The Jewish Chronicle.

During the years 1934-37, Lewis wrote The Revenge for Love (1937). Set in the period leading up to the Spanish Civil War, it is regarded by many as his best novel. It is strongly critical of communist activity in Spain, and presents English intellectual fellow-travelers as deluded.

Lewis' interests and activities in the 1930s, were by no means exclusively political. Despite serious illness necessitating several operations, he was very productive as a critic and painter, and produced a book of poems, One-Way Song, in 1933. He also produced a revised version of Enemy of the Stars, first published in BLAST in 1914, as an example to his literary colleagues of how Vorticist literature should be written. It is a proto-absurdist, Expressionist drama, and some critics have identified it as a precursor to the plays of Samuel Beckett. An important book of critical essays also belongs to this period: Men without Art (1934). It grew out of a defense of Lewis's own satirical practice in The Apes of God, and puts forward a theory of "non-moral," or metaphysical, satire. But the book is probably best remembered for one of the first commentaries on Faulkner, and a famous essay on Hemingway.

Return to painting

After becoming better known for his writing than his painting in the 1920s and early '30s, he returned to more concentrated work on visual art, and paintings from the 1930s and 1940s constitute some of his best-known work. The Surrender of Barcelona (1936-37) makes a significant statement about the Spanish Civil War. It was included in an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1937, that Lewis hoped would re-establish his reputation as a painter. After the publication in The Times of a letter of support for the exhibition, asking that something from the show be purchased for the national collection (signed by, among others, Stephen Spender, W. H. Auden, Geoffrey Grigson, Rebecca West, Naomi Mitchison, Henry Moore, and Eric Gill) the Tate Gallery bought the painting, Red Scene. Like others from the exhibition, it shows an influence from Surrealism and de Chirico's Metaphysical Painting. Lewis was highly critical of the ideology of Surrealism, but admired the visual qualities of some Surrealist art.

Lewis then also produced many of the portraits for which he is well-known, including pictures of Edith Sitwell (1923-36), T.S. Eliot (1938 and again in 1949), and Ezra Pound (1939). The rejection of the 1938 portrait of Eliot by the selection committee of the Royal Academy for their annual exhibition caused a furor, with front-page headlines prompted by the resignation of Augustus John in protest.

The 1940s and after

Lewis spent World War II in the United States and Canada. Artistically, the period is mainly important for the series of watercolor fantasies around the theme of creation that he produced in Toronto in 1941-2. He returned to England in 1945. By 1951, he was completely blind. In 1950, he published the autobiographical Rude Assignment, and in 1952, a book of essays on writers such as George Orwell, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Andre Malraux, entitled The Writer and the Absolute. This was followed by the semi-autobiograpical novel Self Condemned (1954), a major late statement.

The Human Age and retrospective exhibition

The BBC commissioned him to complete the 1928 The Childermass, to be broadcast in a dramatization by D.G. Bridson on the Third Programme and published as The Human Age. The 1928 volume was set in the afterworld, "outside Heaven" and dramatized in fantastic form the cultural critique Lewis had developed in his polemical works of the period. The continuations take the protagonist, James Pullman (a writer), to a modern Purgatory and then to Hell, where Dantesque punishment is inflicted on sinners by means of modern industrial techniques. Pullman becomes chief adviser to Satan (there known as Sammael) in his scheme to undermine the divine and institute a "Human Age." The work has been read as continuing the self-assessment begun by Lewis in Self Condemned. But Pullman is not merely autobiographical; the character is a composite intellectual, intended to have wider representative significance.

In 1956, the Tate Gallery held a major exhibition of his work—Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism. Lewis died in 1957. Always interested in Roman Catholicism, he nevertheless never converted.

Other works include Mrs. Duke's Millions (written around 1908-9 but not published until 1977); Snooty Baronet (a satire on behaviorism, 1932); The Red Priest (his last novel, 1956); Rotting Hill (short stories depicting life in England during the post-war period of "austerity"); and The Demon of Progress in the Arts (on extremism in the visual arts, 1954).

In recent years, there has been a renewal of critical and biographical interest in Lewis and his work, and he is now regarded as a major British artist and writer of the twentieth century.

Notes

- ↑ Shearer West, ed., The Bullfinch Guide to Art History(United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 1996.) ISBN 0-8212-2137-X

- ↑ Twentieth Century London, Program and menu from The Cave of the Golden Calf, Cabaret and Theatre Club, Heddon Street. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ Richard Cork, "Lewis, (Percy) Wyndham (1882-1857)," in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- ↑ Twentieth Century London, Program and menu from The Cave of the Golden Calf, Cabaret and Theatre Club, Heddon Street. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ FluxEuropa, The Art and Ideas of Wyndham Lewis. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ The Modernist Journals Project, Tyro. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ↑ David Ayers, Wyndham Lewis and Western Man (London: Macmillan, 1992).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ayers, David. 1992. Wyndham Lewis and Western Man. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780312071660

- Edwards, Paul. 2000. Wyndham Lewis, Painter and Writer. London: Yale U P. ISBN 9780300082098

- Gasiorek, Andrzej. 2004. Wyndham Lewis and Modernism. Tavistock: Northcote House. ISBN 9780746309520

- Jameson, Fredric. 1979. Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520037922

- Michel, Walter. 1971. Wyndham Lewis: Paintings and Drawings. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01612-2

- O'Keeffe, Paul. 2000. Some Sort of Genius: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis. London: Cape. ISBN 9780224031028

- Schenker, Daniel. 1992. Wyndham Lewis: Religion and Modernism. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817305352

External links

All links retrieved May 20, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.