Evolution

Note: This is only a very rough draft, with notes that may be useful in developing the article. Please do not edit this article until the actual article is complete — i.e., when this notice is removed. You may add comments on what you would like to see included. Rick Swarts 00:05, 28 Sep 2005 (UTC)

- This article is about evolution in the field of biology.

Broadly defined, evolution is any heritiable change in a population of organisms over time. Changes may be slight or large, but must be passed on to the next generation (or many generations) and must involve populations not individuals. Douglas J. Futuyama in Evolutionary Biology (1986) offers a popular definition along these lines: "Biological evolution ... is change in the properties of populations of organisms that transcend the lifetime of a single individual. ... The changes in populations that are considered evolutionary are those that are inheritable via the genetic material from one generation to another." A similar and common definition is: "Evolution can be precisely defined as any change in the frequency of alleles within a gene pool from one generation to the next" (Curtis & Barnes, 1989). Simply put, evolution is a change in the frequency of genes in a population over time. Both a slight change (as in pesticide resistance in a strain of bacteria) and a large change (as in the development of major new designs such as feathered wings for flying, or even the present diversity of life from simple prokaryotes) qualify as evolution.

However, the term evolution is often used with more narrow meanings. It is not uncommon to see the term equated to the specific theory that all organisms have descended from common ancestors (which is also known as the "theory of descent with modification"). On other occasions, evolution is used to refer to one explanation for the process by which change occurs, the "theory of modification through natural selection." Sometimes, the term evolution is used with reference to both the non-causal pattern of descent with modification and the causal mechanism of natural selection.

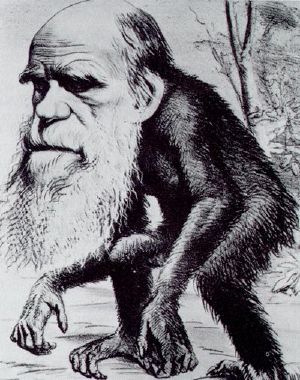

The concept of evolution has often engendered controversy, particularly from religious leaders. In reality, there is a wide variety of religious viewpoints with respect to evolution: from the specific doctrine of "young-earth, scientific creationism," which stands in opposition to descent with modification and natural selection, to views which accept the pattern observed in creation but not the process, to views which attribute a primacy to natural selection. Sometimes conflicts can be traced to terminological confusion, given the diverse ways in which the term is employed. Most controversial is the theory of natural selection, in that it advances three concepts that go against most religious belief: (1) purposelessness (no higher purpose); (2) philosophical materialism; and (3) non-progressive nature of evolution. (See Evolution and Religion, below.)

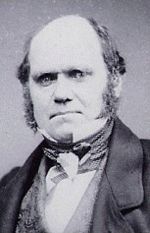

The development of modern theories of evolution began with the introduction of the concept of natural selection in a joint 1858 paper by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, and the publication of Darwin's 1859 book, The Origin of Species. Darwin and Wallace proposed that evolution occurs because a heritable trait that increases an individual's chance of successfully reproducing will become more common, by inheritance, from one generation to the next, and likewise a heritable trait that decreases an individual's chance of reproducing will become rarer. In the 1930s, scientists combined Darwinian natural selection with the re-discovered theory of Mendelian heredity to create the modern synthesis, which is the prevailing paradigm of evolutionary theory.

Evolutionary theory

As broadly and commonly defined in the scientific community, the term evolution deals simply with heritable changes in populations of organisms over time, or changes in the frequencies of alleles over time. The term does not signify any overall pattern of change over time nor the process whereby change occurs — although the term is sometimes used in such a manner.

However, there are two very important and popular evolutionary theories that address the pattern and process of evolution ("theory of descent with modification" and "theory of natural selection," respectively), as well as other concepts in evolutionary theory that deal with speciation and the rate of evolution.

Theory of descent with modification

The "theory of descent with modification" is the major kinematic theory that deals with the pattern of evolution — that is, it treats non-causal relations between ancestral and descendent [species]], orders, phyla, and so forth. The theory of descent with modification essentially postulates that all organisms have descended from common ancestors by a continuous process of branching. In other words, all life evolved from one kind of organism or from a few simple kinds, and each species arose in a single geographic location, from another species that preceded it in time. One of the major contributions of Charles Darwin was to marshal substantial evidence for the theory of descent with modification, particularly in his book, Origin of Species. Among the evidences that evolutionists use to document the "pattern of evolution," are the fossil record, the distribution patterns of existing species, methods of dating fossils, and comparison of homologous structures. (See Evidences of evolution, below.)

Theory of natural selection

Main article: Natural selection

The second major evolutionary theory is the "theory of modification through natural selection." This is a dynamic theory that involves mechanisms and causal relationships. The theory of natural selection is one explanation offered for how evolution might have occurred, i.e, the "process" by which evolution took place to arrive at the pattern.

Natural selection is the process by which biological individuals that are endowed with favorable or deleterious traits end up reproducing more or less than other individuals that do not possess such traits.

According to this theory, natural selection is the directing or creative force of evolution. Natural selection is considered far more than just a minor force for weeding out unfit organisms. Even Paley and other natural theologians accepted natural selection, albeit as a devise for removing unfit organisms, rather than as a directive force for creating new species and new designs.

The theory of natural selection was the most controversial concept advanced by Darwin. While the theory of descent with modification was accepted by the scientific community soon after its introduction, the theory of natural selection took until the mid-1900s to be accepted. This is particularly because the theory of natural selection has three radical components: (a) purposelessness (no higher purpose, just the struggle of individuals to survive and reproduce); (b) philosophical materialism (matter is seen as the ground of all existence with spirit and mind being produced by or a function of the material brain); and (c) the view that evolution is not progressive from lower to higher, but just an adaptation to local environments; it could form a man with his superior brain or a parasite, but no one could say which is higher or lower. Overall, this goes against the concept of design by a Supreme Creator.

Concrete evidence for the theory of modification by natural selection is limited to microevolution — that is, within populations or species. The evidence that natural selection directs changes on the macroevolutionary level, such as the major transitions between species and the origination of new designs, necessarily involves extrapolation from these evidences on the microevolutionary level. One of Darwin's chief purposes in publishing the Origin of Species was to show that natural selection had been the chief agent of the change presented in the theory of descent with modification. The validity of making this extrapolation has recently come under strong challenge from top evolutionists.

Speciation and extinction

Main article: Speciation

The concepts of speciation and extinction are important to any understanding of evolutionary theory.

Speciation is the term that refers to creation of new and distinct biological species by branching off from the ancestral population. Various mechanisms have been presented whereby a single evolutionary lineage splits into two or more genetically independent lineages. For example, [Allopatric speciation]] is held to occur in populations that become isolated geographically, such as by habitat fragmentation or migration. Sympatric speciation is held to occur when new species emerge in the same geographic area. Ernst Mayr's peripatric speciation is a proposal for a type of speciation that exists in between the extremes of allopatry and sympatry, where zones of differentiating species abut but do not overlap. Peripatric speciation is a critical underpinning of the theory of punctuated equilibrium.

Extinction is the disappearance of species (i.e. gene pools). The moment of extinction generally occurs at the death of the last individual of that species. Extinction is not an unusual event in geological time — species are created by speciation, and disappear through extinction. The Permian-Triassic extinction event was the Earth's most severe extinction event, rendering extinct 90% of all marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. In the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event many forms of life perished (including approximately 50% of all genera), the most often mentioned among them being the extinction of the dinosaurs. One of the unheralded laws of evolutionary theory is that once a species becomes extinct it does not re-appear ----------

Rate of evolution

Main article: Punctuated equilibrium

Historically, the view of gradualism dominated evolutionary theory. Gradulism is a view of evolution as proceeding by means of slow accumulation of very small changes, with the evolving population passing through all the intermediate stages — sort of a "march of frequency distributions" through time (Luria et al., 1981).

Darwin himself insisted that evolution was entirely gradual. Indeed, he stated in the Origin of Species:

- "As natural selection acts solely by accumulating slight, successive, favourable variations, it can produce no great or sudden modifications; it can act only by very short and slow steps."

- Nature "can never take a leap, but must advance by the shortest and slowest steps."

- "If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down."

The Darwinian and Neo-Darwinian emphasis on gradualism has been subject to re-examination on several levels: the levels of Major evolutionary trends, origin of new designs, and models of speciation.

Punctuated equilibrium. A common misconception about evolution is that the development of new species requires millions of years. Indeed, the gradualist view that speciation involved a slow, steady, progressive transformation of an ancestral population into a new species has dominated much of evolutionary thought from the time of Darwin. Such a transformation was generally viewed as involving large numbers of individuals ("usually the entire ancestral population", being "even and slow," and occurring "over all or a large part of the ancestral species' geographic range" (Eldredge & Gould 1972). This concept was applied to the development of a new species by either phyletic evolution (where the descendent species arises by the transformation of the entire ancestral population) or by speciation (where the descendent species branches off from the ancestral population).

However, the fossil record does not generally yield the expected sequence of slightly altered intermediary forms, but instead the sudden appearance of species, and long periods when species do not change much.

The theory of punctuated equilibrium ascribes that the fossil record accurately reflects evolutionary change. That is, it posits that macroevolutionary patterns of species are typically ones of morphological stability during their existence, and that most evolutionary change is concentrated in events of speciation— with the origin of a new species usually occurring during geologically short periods of time when the long-term stasis of a population is punctuated by this rare and rapid event of speciation. The sudden transitions between species are sometimes measured on the order of 100s or 1000s of years relative to their millions of years of existence. Although the theory of punctuated equilibria originally generated a lot of controversy, it is now viewed highly favorably in the scientific community, and has even become a part of recent textbook orthodoxy.

Note that the theory of punctuated equilibrium merely addresses the pattern of evolution and is not tied to any one mode of speciation. Although occurring in a brief period of time, the species formation can go through all the stages, or can proceed by leaps. It is even neutral with respect to natural selection.

Punctuated origin of new designs. There is also the issue of the origin of new designs, such as the vertebrate eye, feathers, or jaws in fishes. According to the gradualist viewpoint, the development of key features are explained as having arisen from numerous, tiny, imperceptible steps, with each step being advantageous and developed by natural selection. This style of argument follows Darwin's famous resolution proposed for the origin of the vertebrate eye. To most observers, however, the development of such sophisticated new designs via such a random process as natural selection seems inconceivable, particularly where it cannot be readily imagined how a structure could be useful in incipient stages. One way in which evolutionary theory has dealt with such criticisms is the concept of "preadaptation," proposing that the intermediate stage may perform useful functions different from the final stage).

However, another solution for origin of new designs, which is gaining renewed attention among evolutionists, is that the full sequence of intermediate forms may not have existed at all, and instead key features may have developed by rapid transitions, discontinuously. This view of a punctuational origin of key features arose because of: (1) the persistent problem of the lack of fossil evidence for intermediate stages between major designs, with transitions between major groups being characteristically abrupt; and (2) the inability to conceive of functional intermediates in select cases. Prominent evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould, for example, cites the fur-lined pouches of pocket gophers and the maxillary bone of the upper jaw of certain genera of boid snakes being split into front and rear halves:

How can a jawbone be half broken? . . . What good is an incipient groove or furrow on the outside? Did such hypothetical ancestors run about three-legged while holding a few scraps of food in an imperfect crease with their fourth leg?

Punctuational models of speciation. Punctuational models of speciation are being advanced in contrast with what is sometimes labelled the "allopatric orthodoxy" (Gould, 1980; Gould & Eldredge, 1977). By allopatric orthodoxy, one is referring to a process of species origin involving geographic isolation, whereby a population completely separates geographically from a large parental population and develops gradually into a new species by natural selection until their differences are so great that reproductive isolation ensues. Reproductive isolation is therefore a secondary by-product of geographic isolation, with the process involving gradual allelic substitution. Contrasted with this view are recent punctuational models for speciation, which postulate that reproductive isolation can rise rapidly, not through gradual selection, but without selective significance. In such models, reproductive isolation originates before adaptive, phenotypic differences are aquired. Selection does not play a creative role in initiating speciation, nor in the definitive aspect of reproductive isolation, although it is usually postualated as the important factor in building subsequent adapation. One example of this is polyploidy, where there is a multiplication of the number of chromosomes beyond the normal diploid number. another models is chromosomal speciation, involign large changes in chromosomes due to various genetic accidents.

Darwinism and Neo-Darwinism

Main articles: Darwinism and Modern synthesis

Darwinism is a term generally used as synonymous with the theory of natural selection. As Harvard evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould (1982) has stated: "Although 'Darwinism' has often been equated with evolution itself in popular literature, the term should be restricted to the body of thought allied with Darwin's own theory of mechanism" [natural selection]. Ernst Mayr notes that the term has been used in various ways dependening on who and the time period; nonetheless, Gould concludes that there is a general agreement that "Darwinism should be restricted to the world view encompassed by the theory of natural selection itself."

The term neo-Darwinism is a very different concept. It is considered synonomous with the term "modern synthesis" or "modern evolutionary synthesis." The modern synthesis was the most significant, overall development in evolutionary thought since the time of Darwin, and is the prevailing paradigm of evolutionary biology. The modern synthesis melded the two major theories of classical Darwinism (theory of descent with modification and the theory of natural selection) with the rediscovered Mendelian genetics, recasting Darwin's ideas in terms of changes in allele frequency.

In essence, advances in genetics pioneered by Gregor Mendel led to a sophisticated concept of the basis of variation and the mechanisms of inheritance. Gregor Mendel proposed a gene-based theory of inheritance, discretizing the elements responsible for heritable traits into the fundamental units we now call genes, and laying out a mathematical framework for the segregation and inheritance of variants of a gene, which we now refer to as alleles. Later research identified the molecule DNA as the genetic material through which traits are passed from parent to offspring, and identified genes as discrete elements within DNA. Though largely maintained within organisms, DNA is both variable across individuals and subject to a process of change or mutation.

According to the modern synthesis, the ultimate source of all genetic variation is mutations. They are permanent, transmissible changes to the genetic material (usually DNA or RNA) of a cell, and can be caused by "copying errors" in the genetic material during cell division and by exposure to radiation, chemicals, or viruses.

In addition to passing genetic material from parent to offspring, nearly all organisms employ sexual reproduction to exchange genetic material. This, combined with meiotic recombination, allows genetic variation to be propagated through an interbreeding population.

According to the modern synthesis, natural selection acts on the genes, through their expression (phenotypes). Natural selection can be subdivided into two categories:

- Ecological selection occurs when organisms that survive and reproduce increase the frequency of their genes in the gene pool over those that do not survive.

- Sexual selection occurs when organisms which are more attractive to the opposite sex because of their features reproduce more and thus increase the frequency of those features in the gene pool.

Through the process of natural selection, species become better adapted to their environments. Note that, whereas mutations (and genetic drift) are random, natural selection is not, as it preferentially selects for different mutations based on differential fitnesses.

Evidence of evolution

Main article: Evidence of evolution

For the broad concept of evolution ("any heritiable change in a population of organisms over time"), the evidences of evolution are readily apparent. For example, one sees evolution in creating a particular variety of corn to resist disease or a strain of watermellon to have few seeds. Likewise, the development of a bacteria strain that is resistant to antibiotics or a color change in a population of peppered moths offer evidence of evolution.

Generally, however, when evidences are presented by scholars or textbook authors, the "evidences of evolution" are being presented for either (1) the theory of descent with modification; or (2) a comprehensive concept including both the theory of descent with modification and the theory of natural selection.

In reality, most evidences that are presented are actually for the theory of descent with modification (or theory of common descent). Concrete evidence for the theory of modification by natural selection is limited to microevolution — that is, within populations or species. The evidence that natural selection directs the major transitions between species and originates new designs (macroevolution) involves extrapolation from these evidences on the microevolutionary level. That is, it is inferred that if moths can change their color in 50 years, then new designs or entire new genera can originate over millions of years. If geneticists see population changes for fruit flies in laboratory bottles, then given eons of time, birds can be built from reptiles and fish with jaws from jawless ancestors.

As noted by Gould, "all of the classical arguments for evolution are fundamentally arguments for imperfections that reflect history. They fit the pattern of observing that the leg of Reptile B is not the best for walking, because it evolved from Fish A. In other words, why would a rat run, a bat fly, a porpoise swim and a man type all with the same structures utilizing the same bones unless inherited from a common ancestor?" (source??????)

Evidences for the Theory of Descent With Modification

??Mayr notes that Darwin gave us most of the evidences still used today??

The process of evolution has left behind numerous records which reveal the history of species. While the best-known of these are the fossils, fossils are only a small part of the overall physical record of evolution. Fossils, taken together with the comparative anatomy of present-day plants and animals, constitute the morphological record. By comparing the anatomies of both modern and extinct species, biologists can reconstruct the lineages of those species with some accuracy. Using fossil evidence, for instance, the connection between dinosaurs and birds has been established by way of so-called "transitional" species such as Archaeopteryx.

The development of genetics has allowed biologists to study the genetic record of evolution as well. Although we cannot obtain the DNA sequences of most extinct species, the degree of similarity and difference among modern species allows geneticists to reconstruct lineages with greater accuracy. It is from genetic comparisons that claims such as the 98-99% similarity between humans and chimpanzees come from, for instance.[1]

Other evidence used to demonstrate evolutionary lineages includes the geographical distribution of species. For instance, monotremes and most marsupials are found only in Australia, showing that their common ancestor with placental mammals lived before the submerging of the ancient land bridge between Australia and Asia.

Scientists correlate all of the above evidence – drawn from paleontology, anatomy, genetics, and geography – with other information about the history of the earth. For instance, paleoclimatology attests to periodic ice ages during which the climate was much cooler; and these are found to match up with the spread of species such as the woolly mammoth which are better-equipped to deal with cold.

Fossil record

Fossil evidence of prehistoric organisms has been found all over the Earth. Fossils are traces of once living organisms. Fossilization on an organism is an uncommon occurrence, usually requiring hard parts (like bone) and death where sediments or volcanic ash may be deposited. Fossil evidence of organisms without hard body parts, such as shell, bone, teeth and wood stems, is sparse, but exists in the form of ancient microfossils and the fossilization of ancient burrows and a few soft-bodied organisms. Some insects have been preserved in resin. The age of fossils can often be deduced from the geologic context in which they are found (the strata); and their age also can be determined with radiometric dating. Fossils have been used to determine at what time a lineage developed, and transitional fossils have been proposed to demonstrate continuity between two different lineages.

The comparison of fossils of extinct organisms in older geological strata with fossils found in more recent strata or with living organisms is considered strong evidence of descent with modification. Fossils found in more recent strata are often very similar to, or indistinguishable from living species, whereas the older the fossils the more different from recent fossils or living organisms. In addition, fossil evidence reveals that over time organisms of increasing complexity have appeared on the earth, beginning in the Precambrian Era some 600 millions of years ago with the first eukaryotes.

One of the problems with fossil evidence is the general lack of gradually, sequenced intermediary forms. There are some fossil lineages that appear quite complete, such as from therapsid reptiles to the mammals, and between what is considered land-living ancestors of the whales and their ocean-living descendants. The transition from an ancestral horse (Eohippus) and the modern horse (Equus) is also significant, and Arhaeopteryx has been postualated as fitting the gap between reptiles and birds. But generally, Paleontologists do not find a steady change from ancestral forms to descendent forms, but rather discontinuities, or gaps in most every phyletic series. This has been explained both by the incompleteness of the fossil record, and by proposals of speciation that involve short periods of time, rather than millions of years. (Notably, there are also gaps between living organisms, with a lack of intermediaries between whales and terrestrial mammals, between reptiles and birds, and between flowering plants and their closest relatives.)

The fact that the fossil evidence supports the view that species tend to remain stable throughout their existence and that new species appear suddenly is not problematic for the theory of descent with modification, but only with Darwin's concept of gradualism.

Morphological evidence

The study of comparative anatomy also yields evidence for the theory of descent with modification. It can be observed that various species exhibit a sense of "relatedness," such as various catlike mammals could be put in the same family (Felidae), and doglike mammals in the same family (Canidae), and bears in the same family (Ursidae), and so forth, and then these and other similar mammals could be combined into the same order (Carnivora). This sense of relatedness, from external features, fits the expectations of the Theory of Descent with Modification.

Furthermore, there are structures with similar internal organization that may perform different functions in other species. Vertebrate limbs are a common example of such homologous structures. Bat wings, for example, are very similar to human hands. The forelimes of the human, the penguin, and the alligator are also similar as well, and they derive from the same structures in the embryo.

Also, vestigial organ or structure may exist with little or no purpose in one organism, though they have a clear purpose in other species. The human wisdom teeth and appendix are common examples. Likewise, some snakes have pelvic bones and limb bones, and some blind salamanders have eyes. Such features also would be the prediction of the theory of descent with modifcation, suggesting that they share a common ancestry with organisms that have the same structure, but which is functional.

Phylogeny, the study of the ancestry (pattern and history) of organisms, present a phylogenetic tree to show such relatedness (or a cladogram in other taxonomic disciplines).

Embryology

A common evidence for evolution is the assertion that the embryos of related animals are often quite similar to each other, often much more similar than the adult forms share. For example, it is held that the development of the human embryo is compatible to comparable stages of other kinds of vertebrates (fish, salamander, tortoise, chicken, pig, cow, and rabbit). Generally, the drawings of early embryos by.... Haeckel are given as proof.

It has further been asserted that features, such as the gill pouches in the mammalian embryo which resemble those of fish, are most readily explained as being remnants from the ancestral fish, which were not eliminated because they are embroyonic "organizers" for the next step of development.

However, Wells (***) has pointed out that this evidence is often erroneous, and that ..... Remarkably, even after this has been pointed out, textbook authors have continued to use this proof. Even as a revered evolutionist as Ernst Hackle, in his 2001 text, What Evolution Is, used these same drawings from 1870. Mayr did note that "Haekel (sp.) had fraudulently substituted dog embryos for the human ones, but they were so similar to humans that these (if available) would have made the same point." But Mayr fails to note the other criticisms of this evidence, nor offered more recent drawings to illustrate the point.

Biogeography

The geographic distribution of plants and animals offers another commonly cited evidence for evolution (common descent). The fauna on Australia, with its large marsupials, is very different from that of the other continents. The faunas of Europe and North America are similar, but the fauna on Africa and South America are very different. There are few mammals on oceanic islands. These findings support the Theory of Descent with Modification, which holds that the present distribution of flora and fauna would be related to their common origins and subsequent distribution. The longer the separation of continents, such as with Australia's long isolation, the greater the divergence, for example.

Molecular evidence

Evidence for common descent may be found in traits shared between all living organisms. In Darwin's day, the evidence of shared traits was based solely on visible observation of morphologic similarities, such as the fact that all birds — even those which do not fly — have wings. Today, the theory of common descent is supported by genetic similarities. For example, every living cell makes use of nucleic acids as its genetic material, and uses the same twenty amino acids as the building blocks for proteins. All organisms use the same genetic code (with some extremely rare and minor deviations) to translate nucleic acid sequences into proteins. The universality of these traits strongly suggests common ancestry, because the selection of these traits seems somewhat arbitrary.

Similarly, the metabolism of very different organisms are based on the same biochemistry. For example, the protein cytochrome c, which is needed for aerobic respiration, is universally shared in aerobic organisms, suggesting a common ancestor that used this protein. There are also variations in the amino acid sequence of cytochrome C, with the more similar molecules found in organisms that appear more related (monkeys and cows) than between those that seem less related (monkeys and fish). The cytochorme c of chimpanzees is the same as that of humans, but very different from bread mold. Similar results have been found with blood proteins.

Other uniformity is seen in the universality of mitosis in all cellular organisms, the similarity of meiosis in all sexually reproducing organisms, the use of ATP by all organisms for energy transfer, and the fact that almost all plants use the same chlorophyll molecule for photosynthesis.

Likewise, the closer that organisms appear to be related, the more similar are their respective molecules. That is, comparison of the genetic sequence of organisms reveals that phylogenetically close organisms have a higher degree of sequence similarity than organisms that are phylogenetically distant. For example, neutral human DNA sequences are approximately 1.2% divergent (based on substitutions) from those of their nearest genetic relative, the chimpanzee, 1.6% from gorillas, and 6.6% from baboons. Sequence comparison is considered a measure robust enough to be used to correct erroneous assumptions in the phylogenetic tree in instances where other evidence is scarce.

Comparative studies also show that some basic genes of higher organisms are shared with homologous genes in bacteria.

Further evidence for common descent comes from genetic detritus such as pseudogenes, regions of DNA which are orthologous to a gene in a related organism, but are no longer active and appear to be undergoing a steady process of degeneration.

Evidences for the Theory of Natural Selection

Evidences of natural selection are seen on the microevolutionary level, which refers to events and processes at or below the level of species. Plant and animal breeders use artificial selection to produce different varities of plants, strains of fish, and types of cows and horses. Natural selection is seen in the changes of the shade of gray of populations of peppered moths (Biston betularia), observed in England.

However, at question has always been the sufficiency of extrapolation to the macroevolutionary level. As Mayr (2001) notes, "from Darwin's day to the present, there has been a heated controversy over whether macroevolution is nothing but an unbroken continuation of microevolution, as Darwin and his followers have claimed, or rather is disconnected from microevolution."

Teaching of evidences

Textbook authors have often confused the dialogue on evolution by treating the term as if it signified one unified whole — not only descent with modification, but also the specific Darwinian and neo-Darwinian theories regarding natural selection, gradualism, speciation, and so forth. Certain textbook authors, in particular, have exacerbated this terminological confusion by lumping "evidences of evolution" into a section placed immediately after a comprehensive presentation on Darwin's overall theory — thereby creating the misleading impression that the evidences are supporting all components of Darwin's theory, including natural selection. In reality, the confirming information is invariably limited to the phenomenon of evolution having occurred (descent from a common ancestor or change of gene frequencies in populations), or perhaps including evidence of natural selection within populations.

History of Life

The appearance of life on earth (see Origin of life) is not a part of biological evolution.

Not much is known about the earliest developments in life. However, all existing organisms share certain traits, including cellular structure and genetic code. Most scientists interpret this to mean all existing organisms share a common ancestor that had already developed the most fundamental cellular processes. There is no scientific consensus on the relationship of the three domains of life (Archea, Bacteria, Eukaryota) or the origin of life.

The emergence of oxygenic photosynthesis (around 3 billion years ago) and the subsequent emergence of an oxygen-rich, non-reducing atmosphere can be traced through the formation of banded iron deposits, and later red beds of iron oxides. This was a necessary prerequisite for the development of aerobic cellular respiration, believed to have emerged around 2 billion years ago.

In the last billion years, simple multicellular plants and animals began to appear in the oceans. Soon after the emergence of the first animals, the Cambrian explosion (a period of unrivaled and remarkable, but brief, organismal diversity documented in the fossils found at the Burgess Shale) saw the creation of all the major body plans, or phyla, of modern animals. About 500 million years ago, plants and fungi colonized the land, and were soon followed by arthropods and other animals, leading to the development of land ecosystems with which we are familiar.

Evolution and Religion

need to add intelligent design (as this article is a portal article really)

There is a wide variety of religious viewpoints with respect to evolution: from the specific doctrine of Ascientific creationism,@ which stands in opposition to evolution, to views which accept the pattern observed in creation but not the process, to views which attribute a primacy to natural selection. Millions of religious adherents do successfully juxtapose the two viewpoints of evolution and creationism. As eminent evolutionary geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky stated, AIt is wrong to hold creation and evolution as mutually exclusive alternatives. I am a creationist and an evolutionist. Evolution is God=s or Nature=s, method of creation.@

In particular, the theory of descent with modification would seem to pose no difficulty whatever to most religious adherents, since it is neutral with respect to the process. The mechanism that gives rise to the pattern could occur by natural selection or it could occur by the directive force of a supreme being.

Some of the confusion in the dialogue between evolutionists and creationists is what is being referred to by the term Aevolution@ or Atheory of evolution.@ For evolutionists, a working definition of the term "evolution" is generally descent with modification or a change of gene frequencies in populations.

Since there is considerable experimental and observational evidence of populations systematically changing over time, evolutionists speak of "the fact of evolution." There is evidence on the microevolutionary level (change in gene frequencies within populations), in terms of artificial selection or the change in the color of the peppered moths. On a macroevolutionary level (large-scale events such as speciation and origin of new designs), various evidences such as fossil records, biogeography, and studies of homologies have strongly supported the view that all organisms have descended from common ancestors. In fact, renowned evolutionist Mayr contends that Athe facts of biogeography posed some of the most insoluble dilemmas for the creationists and were eventually used by Darwin as his most convincing evidence in favor of evolution.@

Darwin helped to establish the "fact of evolution." In 1859, most scientists and laymen believed that the world was constant. The massive evidence that Darwin presented was so convincing that within a few years every biologist became an evolutionist, believing that the world was the product of a continuing process of change. For most biologists today, evolution is no longer a theory but simply a fact. They may disagree with the mechanisms, but that evolution takes place — that there is a systematic change in populations — is unquestioned.

The statement that Aevolution is a fact,@ draws the ire of scientific creationists, of course. However, scientific creationists represent only a small body of those individuals that do believe in a creation by a supreme being. Nonetheless, other religious adherents likewise often speak of opposition to evolution, despite having a belief system which allows descent with modification and change in gene frequencies in populations. There are a couple of ready explanations for this.

For one, there is the case of terminological confusion. When some individuals and religious adherents use the term Aevolution,@ they are not referring to simply a systematic change in populations over time — which is a highly established fact — but are instead treating the word Aevolution@ as synonymous with the specific Darwinian theory of evolution by natural selection — a theory with which even some eminent evolutionists find troublesome as the sole explanation for observed changes. Thus, religious adherents may reject Aevolution@ since they see the concept of randomness in natural selection as counter to their belief that a Supreme Being directs changes

Although concepts of evolution were not uncommon in the first half of the nineteenth century, Darwin 's theory had three radical components for its day:

Purposeless. A higher purpose was not required or utilized to explain the seeming harmony in the world. The orthodox view at the time was that one observed harmony in nature because everything had a preordained role. Darwin's theory cut through this orthodoxy with the view that there was no higher purpose — simply the struggle of individuals to survive and reproduce. Philosophical materialism. Philosophical materialism holds that matter is the main reality of existence and mental and spiritual phenomena, including thought, will and feeling, can be explained in terms of matter, as its by-products. By advocating a materialist account of life, Darwin went against one of the strongest traditions of Western thought: the separation of mind and matter, with an elevated status for mind. Rather, in Darwin's view, the human mind was a natural outcome of selective pressures for a large and complex brain. Evolution as not inherently progressive. Darwin stated that evolution was not inherently progressive, inexorably leading to an improvement of life over time. That is, life does not move from lower to higher states, and indeed, there is no "higher" or "lower" with reference to the structure of organisms. Natural selection only adapts organisms to their local environments. It could lead to evolving a human, but also produced the extreme morphological degeneration of many parasites. Darwin granted humans no special status.

Furthermore, popular writings often tend to create an artificial dichotmy B either belief in a Creator is correct or evolution is correct B an Aeither-or dichotomy@ which tends to foster an erroneous view of the relationship between evolution and religion. By such means, evolution and religion (specifically creation by a God) are presented as if mutually exclusive alternatives. Thus, many religious adherents reject evolution out of hand, not wishing to reject God.

Social and religious controversies

There has been constant controversy surrounding the ideas presented by The Origin of Species since it was first printed in 1859. Since the early twentieth century, however, the idea that biological evolution of some form occurred and is responsible for speciation has been almost completely uncontested within the scientific community.

Most controversy over the theory has come because of its philosophical, cosmological, and religious implications, and supporters as well as detractors have interpreted it as generally indicating that human beings are, like all animals, evolved, and that this account of the origins of humankind is squarely at odds with many religious interpretations. The idea that humans are "merely" animals, and are genetically very closely related to primates, have been independently argued as repellent notions by generations of detractors.

Others also intepreted the truth of the theory to imply varying types of social changes — one prominent example is the idea of eugenics, formulated by Darwin's cousin Francis Galton, which argues for the improvement of human heredity by means of political policies. Others have found different political interpretations which have been used as arguments both for and against the theory.

The questions raised about the relation of evolution to the origins of humans has made it an especially tenacious issue with religious traditions. It has prominently been seen as opposing a "literal" interpretation of the account of the origins of humankind as described in Genesis, the first book of the Bible. In many countries — notably in the United States — this has led to what has been called the Creation-evolution controversy, which has focused primarily on struggles over teaching curriculum.

Science: fact and theory

The word "evolution" has been used to refer both to a fact and a theory, and it is important to understand both these different meanings of evolution, and the relationship between fact and theory in science.

Evolution as fact and theory

When "evolution" is used to describe a fact, it refers to the observations that populations of one species of organism do, over time, change into new, or several new, species. In this sense, evolution occurs whenever a new strain of bacterium evolves that is resistant to antibodies that had been lethal to prior strains.

Another clear case of evolution as fact involves the hawthorn fly, Rhagoletis pomonella. Different populations of hawthorn fly feed on different fruits. A new population spontaneously emerged in North America in the 19th century some time after apples, a non-native species, were introduced. The apple feeding population normally feeds only on apples and not on the historically preferred fruit of hawthorns. Likewise the current hawthorn feeding population does not normally feed on apples. A current area of scientific research is the investigation of whether or not the apple feeding race may further evolve into a new species. Some evidence, such as the fact that six out of thirteen alozyme loci are different, that hawthorn flies mature later in the season, and take longer to mature, than apple flies, and that there is little evidence of interbreeding (researchers have documented a 4-6%hybridization rate) suggests that this is indeed ocurring.[2] (see Berlocher and Bush 1982, Berlocher and Feder 2002, Bush 1969, McPheron et. al. 1988, Prokopy et. al. 1988, Smith 1988)

When "evolution" is used to describe a theory, it refers to an explanation for why and how evolution (for example, in the sense of "speciation") occurs. An example of evolution as theory is the modern synthesis of Darwin and Wallace's theory of natural selection and Mendel's principles of genetics. This theory has three major aspects:

- Common descent of all organisms from a single ancestor or ancestral gene pool.

- Manifestation of novel traits in a lineage.

- Mechanisms that cause some traits to persist while others perish.

When people provide evidence for evolution, in some cases they are providing evidence that evolution occurs; in other cases they are providing evidence that a given theory is the best explanation yet as to why and how evolution occurs.

The meaning of, and relationship between, fact and theory in science

- Main article: Theory

The modern synthesis, like its Mendelian and Darwinian antecedents, is a scientific theory. In plain English, people use the word "theory" to signify "conjecture", "speculation", or "opinion". In this popular sense, "theories" are opposed to "facts" — parts of the world, or claims about the world, that are real or true regardless of what people think. In scientific terminology however, a theory is a model of the world (or some portion of it) from which falsifiable hypotheses can be generated and tested through controlled experiments, or be verified through empirical observation. In this scientific sense, "facts" are parts of theories – they are things, or relationships between things, that theories must take for granted in order to make predictions, or that theories predict. In other words, for scientists "theory" and "fact" do not stand in opposition, but rather exist in a reciprocal relationship – for example, it is a "fact" that an apple dropped on earth will fall towards the center of the planet in a straight line, and the "theory" which explains it is the current theory of gravitation. In this same sense evolution is a fact and modern synthesis is currently the most powerful theory explaining evolution, variation and speciation. Within the science of biology, modern synthesis has completely replaced earlier accepted explanations for the origin of species, including Lamarckism and creationism.

History of evolutionary thought

The idea of biological evolution has existed since ancient times, notably among Hellenists such as Epicurus and Anaximander, but the modern theory was not established until the 18th and 19th centuries, by scientists such as Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Charles Darwin. While transmutation of species was accepted by a sizeable number of scientists before 1859, it was the publication of Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species which provided the first cogent mechanism by which evolutionary change could occur: his theory of natural selection. Darwin was motivated to publish his work on evolution after receiving a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace, in which Wallace revealed his own discovery of natural selection. As such, Wallace is sometimes given shared credit for the theory of evolution.

Darwin's theory, though it succeeded in profoundly shaking scientific opinion regarding the development of life, could not explain the source of variation in traits within a species, and Darwin's proposal of a hereditary mechanism (pangenesis) was not compelling to most biologists. It was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that these mechanisms were established.

When Gregor Mendel's work regarding the nature of inheritance in the late 19th century was "rediscovered" in 1900, it led to a storm of conflict between Mendelians (Charles Benedict Davenport) and biometricians (Walter Frank Raphael Weldon and Karl Pearson), who insisted that the great majority of traits important to evolution must show continuous variation that was not explainable by Mendelian analysis. Eventually, the two models were reconciled and merged, primarily through the work of the biologist and statistician R.A. Fisher. This combined approach, applying a rigorous statistical model to Mendel's theories of inheritance via genes, became known in the 1930s and 1940s as the modern evolutionary synthesis.

In the 1940s, following up on Griffith's experiment, Avery, McCleod and McCarty definitively identified deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) as the "transforming principle" responsible for transmitting genetic information. In 1953, Francis Crick and James Watson published their famous paper on the structure of DNA, based on the research of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. These developments ignited the era of molecular biology and transformed the understanding of evolution into a molecular process: the mutation of segments of DNA (see molecular evolution).

George C. Williams' 1966 Adaptation and natural selection: A Critique of some Current Evolutionary Thought marked a departure from the idea of group selection towards the modern notion of the gene as the unit of selection. In the mid-1970s, Motoo Kimura formulated the neutral theory of molecular evolution, firmly establishing the importance of genetic drift as a major mechanism of evolution.

Debates have continued within the field. One of the most prominent public debates was over the theory of punctuated equilibrium, proposed in 1972 by paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould to explain the paucity of transitional forms between phyla in the fossil record.

Disciplines in evolutionary studies

Scholars in a number of academic disciplines and subdisciplines document the fact of evolution, and contribute to the theory of evolution.

Physical anthropology

Physical anthropology emerged in the late 1800s as the study of human osteology, and the fossilized skeletal remains of other hominids. At that time anthropologists debated whether their evidence supported Darwin's claims, because skeletal remains revelaed temporal and spacial variation among hominids, but Darwin had not offered an explanation of the mechanisms that produce variation. With the recognition of Mendelian genetics and the rise of the modern synthesis, however, evolution became both the fundamental conceptual framework for, and object of study of, physical anthropologists. In addition to studying skeletal remains, they began to study genetic variation among human populations (i.e. population genetics; thus, some physical anthropologists began calling themselves biological anthropologists.

Evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is a subfield of biology concerned with the origin and descent of species, as well as their change over time.

At first it was an interdisciplinarity field including scientists from many traditional taxonomically oriented disciplines. For example, it generally includes scientists who may have a specialist training in particular organisms such as mammalogy, ornithology, or herpetology but use those organisms as systems to answer general questions in evolution.

Evolutionary biology as an academic discipline in its own right emerged as a result of the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s. It was not until the 1970s and 1980s, however, that a significant number of universities had departments that specifically included the term evolutionary biology in their titles.

Evolutionary developmental biology

Evolutionary developmental biology is an emergent subfield of evolutionary biology that looks at genes of related and unrelated organisms. By comparing the explicit nucleotide sequences of DNA/RNA, it is possible to experimentally determine and trace timelines of species development. For example, gene sequences support the conclusion that chimpanzees are the closest primate ancestor to humans, and that arthropods (e.g., insects) and vertebrates (e.g., humans) have a common biological ancestor.

See also

|

|

Notes and references

- ^ "Ancient microfossils from Western Australia are again the subject of heated scientific argument: are they the oldest sign of life on Earth, or just a flaw in the rock?" "[3]"

- ^ Understanding Evolution, from California's Berkeley University. "[4] [5]

- ^ Li WH, Saunders MA (2005) Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature 437: 69–87. Britten RJ (2002) Divergence between samples of chimpanzee and human DNA sequences is 5%, counting indels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 13633–13635.

- ^ Two sources: 'Genomic divergences between humans and other hominoids and the effective population size of the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees'. and 'Quantitative Estimates of Sequence Divergence for Comparative Analyses of Mammalian Genomes' "[6] [7]"

- ^ Pseudogene evolution and natural selection for a compact genome. "[8]"

- ^ Reference for emergence of new race of apple maggot flies [[9]]

- ^ Evaluation of the Rate of Evolution in Natural Populations of Guppies (Poecilia reticulata) "[10]"

- ^ The use of evolutionary principles to guide disease diagnosis and drug development with respect to bird flu (i.e. H5N1 virus) [11]

- ^ Understanding Evolution, from California's Berkeley University: "Sex can introduce new gene combinations into a population. This genetic shuffling is another important source of genetic variation."[12]

- Berlocher, S.H. and G.L. Bush. 1982. An electrophoretic analysis of Rhagoletis (Diptera: Tephritidae) phylogeny. Systematic Zoology 31:136-155.

- Berlocher, S.H. and J.L. Feder. 2002. Sympatric speciation in phytophagous insects: moving beyond controversy? Annual Review of Entomology 47:773-815.

- Bush, G.L. 1969. Sympatric host race formation and speciation in frugivorous flies of the genus Rhagoletis (Diptera: Tephritidae). Evolution 23:237-251.

- Darwin, Charles November 24 1859. On the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. 502 pages. Reprinted: Gramercy (May 22, 1995). ISBN 0517123207

- Prokopy, R.J., S.R. Diehl and S.S. Cooley. 1988. Behavioral evidence for host races in Rhagoletis pomonella flies. Oecologia 76:138-147.

- Zimmer, Carl. Evolution: The Triumph of an Idea. Perennial (October 1, 2002). ISBN 0060958502

- Larson, Edward J. Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory (Modern Library Chronicles). Modern Library (May 4, 2004). ISBN 0679642889

- Mayr, Ernst. What Evolution Is. Basic Books (October, 2002). ISBN 0465044263

- McPheron, B. A., D. C. Smith and S. H. Berlocher. 1988. Genetic differentiation between host races of Rhagoletis pomonella. Nature. 336:64-66.

- Gigerenzer, Gerd, et al., The empire of chance: how probability changed science and everyday life (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

- Smith, D. C. 1988. Heritable divergence of Rhagoletis pomonella host races by seasonal asynchrony. Nature. 336:66-67.

- Williams, G.C. (1966). Adaptation and Natural Selection: A Critique of some Current Evolutionary Thought . Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Sean B. Carroll, 2005, Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo and the Making of the Animal Kingdom, W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393060160

- Bill Bryson, A Short History of Nearly Everything, Black Swan Books (2004), ISBN 0-552-99704-8

External links

- Talk.Origins Archive — see also talk.origins

- Understanding Evolution @ Berkeley

- National Academies Evolution Resources

- EvoWiki — A wiki whose goal is to promote general evolution education, and provide mainstream scientific responses to the arguments of antievolutionists.

- Evolution by Natural Selection — An introduction to the logic of the theory of evolution by natural selection

- Evolution — Provided by PBS.

- Everything you wanted to know about evolution — Provided by New Scientist.

- International Journal of Organic Evolution

- Howstuffworks.com — How Evolution Works

- Charles Darwin's writings

- Evolution News from Genome News Network (GNN)

- National Academy Press: Teaching About Evolution and the Nature of Science

- Evolution for beginners

- RMCybernetics - AI Evolution can create emergent behavior in a computer program.

- NPR - Science Friday: links to museums, articles and books.

Evolution Simulators

- Isolated species evolves to interact more efficiently with its environment (java applet)

- Evolution in a predator-prey relationship (java applet)

| Basic topics in evolutionary biology | (edit) |

|---|---|

| Processes of evolution: evidence - macroevolution - microevolution - speciation | |

| Mechanisms: natural selection - genetic drift - gene flow - mutation - phenotypic plasticity | |

| Modes: anagenesis - catagenesis - cladogenesis | |

| History: History of evolutionary thought - Charles Darwin - The Origin of Species - modern evolutionary synthesis | |

| Subfields: population genetics - ecological genetics - human evolution - molecular evolution - phylogenetics - systematics |

af:Evolusie ar:نظرية النشوء bn:বিবর্তন ca:Teoria de l'evolució cs:Evoluce cy:Esblygiad da:Evolution de:Biologische Evolution es:Evolución biológica eo:Evoluismo fa:فرگشت fr:Évolution ko:진화 id:Evolusi it:Evoluzione he:אבולוציה lt:Evoliucija lb:Evolutioun hu:Evolúció mk:Еволуција nl:Evolutietheorie ja:進化 no:Evolusjon pl:Ewolucja biologiczna pt:Evolução ro:Teoria evoluţionistă ru:Эволюционное учение sl:Evolucija sk:Evolúcia su:Évolusi fi:Evoluutio sv:Evolution th:วิวัฒนาการ tr:Evrim zh:进化论

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

From Encylopedia Britannica: Biological theory that animals and plants have their origin in other preexisting types and that the distinguishable differences are due to modifications in successive generations. It is one of the keystones of modern biological theory. In 1858 Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace jointly published a paper on evolution. The next year Darwin presented his major treatise On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, which revolutionized all later biological study. The heart of Darwinian evolution is the mechanism of natural selection. Surviving individuals, which vary (see variation) in some way that enables them to live longer and reproduce, pass on their advantage to succeeding generations. In 1937 Theodosius Dobzhansky applied Mendelian genetics (see Gregor Mendel) to Darwinian theory, contributing to a new understanding of evolution as the cumulative action of natural selection on small genetic variations in whole populations. Part of the proof of evolution is in the fossil record, which shows a succession of gradually changing forms leading up to those known today. Structural similarities and similarities in embryonic development among living forms also point to common ancestry. Molecular biology (especially the study of genes and proteins) provides the most detailed evidence of evolutionary change. Though the theory of evolution is accepted by nearly the entire scientific community, it has sparked much controversy from Darwin's time to the present; many of the objections have come from religious leaders and thinkers (see creationism) who believe that elements of the theory conflict with literal interpretations of the Bible. See also Hugo de Vries, Ernst Haeckel, human evolution, Ernst Mayr, parallel evolution, phylogeny, sociocultural evolution, speciation.