Difference between revisions of "Diaspora" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ready}} | + | {{ready}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

| + | [[Image:Lakhva.jpg|thumb|300px|A Jewish neighborhood in Poland in 1926]] | ||

| − | The term '''diaspora''' (in [[Ancient Greece|Ancient Greek]], '''διασπορά''' – "''a scattering or sowing of seeds''") refers to any people or [[ethnicity|ethnic]] population | + | The term '''diaspora''' (in [[Ancient Greece|Ancient Greek]], '''διασπορά''' – "''a scattering or sowing of seeds''") refers to any people or [[ethnicity|ethnic]] population forced or induced to leave its traditional [[homeland]], as well as the dispersal of such people and the ensuing developments in their culture. It is especially used with reference to the [[Jews]], who have lived most of their historical existence as a ''diasporan'' people. |

| − | + | The Jewish diaspora began with the conquests of the eighth to the sixth century B.C.E.., when the [[Israelites]] were forcibly exiled first from the northern [[kingdom of Israel]] to [[Assyria]] and then from the southern [[kingdom of Judah]] to [[Babylon]]. Although some later returned to [[Judea]], Jews continued to settle elsewhere during the periods of the Greek and Roman empires. Major centers of Jewish diasporan culture emerged in such places as [[Alexandria, Egypt|Alexandria]], [[Asia Minor]], and Babylonia. A second major expulsion of Jews from the [[Holy Land]] took place as a result of destruction of the [[Second Temple]] in the wake of the [[Jewish Revolt]] of 70 C.E. and the subsequent [[Bar Kokhba]] revolt. From the mid-second century onward, '''diaspora''' was the normative experience of Jews until the establishment of the state of [[Israel]] in 1948. The majority of Jews today are still a diasporan people. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | Many other ethnic and religious groups also live in diaspora in the contemporary period as a result of wars, relocation programs, economic hardship, natural disasters, and political repression. Thus, it is common today to speak of an [[Africa]]n diaspora, [[Muslim]] diaspora, [[Greek]] diaspora, [[Korean diaspora]], [[Tibetan]] diaspora, etc. Diasporan peoples, by their exposure to other cultures, often play a role in broadening the outlook of their homeland populations, increasing the potential for pluralism and tolerance. | |

==Jewish diaspora== | ==Jewish diaspora== | ||

| − | The Jewish diaspora([[Hebrew language|Hebrew]]: ''Tefutzah'' | + | The Jewish diaspora ([[Hebrew language|Hebrew]]: ''Tefutzah,'' "scattered," or ''Galut'' גלות, "exile") was the result of the expulsion of the Jews from the [[land of Israel]], voluntary migrations, and, to a lesser extent, [[religious conversion]]s to [[Judaism]] in lands other than Israel. The term was originally used by the [[Ancient Greeks]] to describe citizens of a dominant city-state who emigrated to a conquered land with the purpose of colonization, such as those who colonized [[Egypt]] and [[Syria]]. The earliest use of the word in reference specifically to Jewish exiles is in the [[Septuagint]] version of [[Deuteronomy]] 28:25: "Thou shalt be a ''dispersion'' in all kingdoms of the earth." |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Pre-Roman diaspora=== | ===Pre-Roman diaspora=== | ||

| − | + | In 722 B.C.E., the [[Assyria]]ns under [[Shalmaneser V]] conquered the northern [[kingdom of Israel]], and many [[Israelites]] were deported to the Assyrian province of [[Khorasan]]. Since then, for over 2700 years, the [[Persian Jews]] have lived in the territories of today's [[Iran]]. | |

| − | In 722 B.C.E., the [[ | ||

| − | After the overthrow in of the | + | After the overthrow in of the [[Kingdom of Judah]] by [[Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon]] and the subsequent deportation of a considerable portion of its inhabitants to [[Mesopotamia]] beginning in 588 B.C.E., the Jews had two principal cultural centers: [[History of the Jews in Iraq|Babylonia]] and the [[Judea]]. The more pious elements among the exiles returned to Judea during the [[Achaemenid Persian Empire]] (550–330 B.C.E.). With the reconstructed [[Temple in Jerusalem]] as their center, they reorganized themselves into a community animated by a remarkable religious ardor and a tenacious attachment to the [[Torah]], which thenceforth constituted the focus of Jewish identity. |

| − | + | Owing to internal dissensions in the [[Seleucid Empire|Seleucid dynasty]] (312 - 63 B.C.E.) and to the support of the Romans, the cause of Jewish independence temporarily triumphed under the [[Hasmonean]] princes. The Jewish state prospered and even annexed several territories, but discord in the royal family and the growing disaffection of the religious elements made the Jewish nation an easy prey to the ambition of the growing Roman Empire. In 63 B.C.E., the military commander [[Pompey]] invaded [[Jerusalem]], and the Jewish nation became a vassal of Rome. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===The diaspora in Roman times=== | ===The diaspora in Roman times=== | ||

| + | Jews were already widespread in the [[Roman Empire]] by the middle of the second century B.C.E., when the Jewish author of the third book of the [[Sibylline oracles]], addressing the "[[chosen people]]," says: "Every land is full of thee and every sea." Diverse witnesses, such as [[Strabo]], [[Philo]], [[Seneca the Younger|Seneca]], [[Luke the Evangelist|Luke]] (the author of the ''Acts of the Apostles''), [[Cicero]], and [[Josephus]], all mention Jewish populations in the cities of the Mediterranean. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Sack of jerusalem.JPG|thumb|300px|In Rome the [[Arch of Titus|Arch]] of [[Titus]] still stands, depicting the enslaved Judeans and objects from the Temple being brought to Rome.]] | |

| − | [[ | + | [[Alexandria]] was by far the most important of the diasporan Jewish communities. [[Philo of Alexandria]] (d. 50 C.E.) gives the number of Jewish inhabitants in [[Egypt]] as one million, one-eighth of the population. Babylonia also had a very large Jewish population, as many Jews had never returned from there to Judea. The number of Jewish residents in [[Cyprus]] and in [[Mesopotamia]] was also large. It has been estimated that there were also about 180,000 Jews in Asia Minor in the year 62/61 B.C.E. In the city of Rome, at the commencement of the reign of [[Caesar Augustus]], there were well over 7000 Jews. |

| − | + | King [[Agrippa I]] (d. 44 C.E.), in a letter to [[Caligula]], enumerated communities of the Jewish diaspora in almost all the Hellenized and non-Hellenized countries of the Orient. According to the first-century Jewish historian [[Josephus]], the Jewish population outside of Israel and [[Babylonia]] was densest in [[Syria]], particularly in [[Antioch]] and [[Damascus]]. Some 10,000-18,000 Jews were reportedly massacred at Damascus during the [[Jewish Revolt]] of 70 C.E.; Jerusalem was destroyed, and Greek and Roman colonies were established in Judea to prevent the political regeneration of the Jewish nation. However, Jews sought to establish commonwealths in Cyrene, Cyprus, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. These efforts were suppressed by [[Trajan]] during the persecutions of 115-117. The attempt of the Jews of Palestine to regain their independence during the [[Bar Kochba]] revolt (132-135) was even more brutally crushed. | |

| − | |||

| − | King [[Agrippa I]] (d. 44 C.E.), in a letter to [[Caligula]], | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

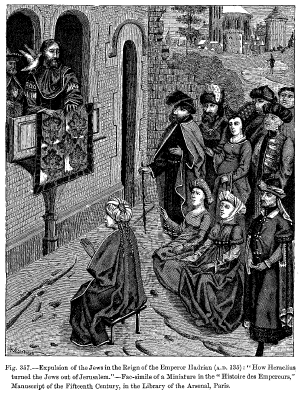

[[Image:Expulsion of the Jews in the Reign of the Emperor Hadrian AD 135 How Heraclius turned the Jews out of Jerusalem Fac simile of a Miniature in the Histoire des Empereurs Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century.png||thumb|Expulsion of the Jews in the reign of Emperor [[Hadrian]] (135 C.E.)]] | [[Image:Expulsion of the Jews in the Reign of the Emperor Hadrian AD 135 How Heraclius turned the Jews out of Jerusalem Fac simile of a Miniature in the Histoire des Empereurs Manuscript of the Fifteenth Century.png||thumb|Expulsion of the Jews in the reign of Emperor [[Hadrian]] (135 C.E.)]] | ||

| − | From this time on, the Jews of Palestine | + | From this time on, the Jews of Palestine were greatly reduced in numbers, destitute, and crushed. As a result, they began to lose their preponderant influence in the Jewish world, and the center of spirituality shifted from the [[Jerusalem]] priesthood to the [[rabbinic tradition]] based in the local [[synagogue]]s. Jerusalem, renamed as "[[Ælia Capitolina]]," had become a Roman colony, a city entirely [[pagan]]. Jews were forbidden entrance, under pain of death. Some, like Rabbi [[Akiva]], suffered [[martyr]]dom as a result. |

| − | + | Nevertheless, in the sixth century there were 43 Jewish communities in Palestine, scattered along the coast, in the [[Negev]], east of the Jordan, and in villages in the [[Galilee]] region, and in the [[Jordan River]] valley. Jewish communities expelled from [[Judea]] were sent, or decided to go, to various Roman provinces in the [[Middle East]], [[Europe]], and [[North Africa]]. | |

===Post-Roman diaspora=== | ===Post-Roman diaspora=== | ||

| + | Jews in the diaspora had been generally accepted into the [[Roman Empire]], but with the rise of [[Christianity]], restrictions against them grew. With the advent of [[Islam]], Jews generally fared better in [[Muslim]] lands that Christian ones. The center of Jewish intellectual life thus shifted from Christian areas to Muslim [[Babylonia]], which had already been developing a strong academic tradition at the great [[yeshiva]]s of Sura and Pumpedita. These centers also developed the Babylonian [[Talmud]], which came to be seen as more authoritative than its Palestinian counterpart as the key text of Jewish [[halakha|religious law and custom]]. | ||

| − | + | During the [[Middle Ages]], Jews gradually moved into [[Europe]], settling first in Muslim [[Spain]] and later in the Christian areas of the [[Rhineland]]. The Jewish diaspora thus divided into distinct regional groups which today are generally addressed according to two main divisions: the [[Ashkenazi]] (Northern and Eastern European Jews) and [[Sephardic]] Jews (Spanish and Middle Eastern Jews). | |

| − | + | The Christian [[Reconquista|reconquest of Spain]] led ultimately to the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula beginning in the late fifteenth century. Many of these Sephardic Jews fled to [[Italy]] others the [[Netherlands]] and northern Europe, with still others going to the Middle East or Northern Africa. Meanwhile, the Ashkenazi population was growing rapidly. In 1764, there were about 750,000 Jews in the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]]. The worldwide Jewish population at that time is estimated at 1.2 million, mainly in Europe, [[Russia]], and throughout the [[Ottoman Empire]]. | |

| − | + | Expulsions, [[ghetto]]ization, and [[pogrom]]s haunted the Jews wherever they went in the Christian world, and the difficulty of Jewish life in the diaspora was a key factor in the advent of [[Zionism]]. Underlying this attitude was the feeling that the diaspora restricted the full growth of Jewish national life, coupled with the messianic current of Jewish religious thought, which looked to the [[Messiah]] as a [[David]]ic descendant who will restore Jewish sovereignty in the [[Holy Land]]. The pogroms of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and the [[Holocaust]] of European Jews during [[WWII]] made many Jews feel that life in the diaspora could not be sustained without a Jewish state to which persecuted Jews could return if they desired. | |

===Jewish diaspora today=== | ===Jewish diaspora today=== | ||

| − | The establishment of [[Israel]] as a Jewish state in 1948 meant that henceforth, living in the diaspora became a matter of choice | + | The establishment of [[Israel]] as a Jewish state in 1948 meant that henceforth, living in the diaspora became a matter of choice rather than of necessity for many Jews. However, until the fall of [[Communism]], Jews living in the former [[Soviet bloc]] were often forbidden to immigrate, while others faced economic obstacles. |

| − | While a large proportion of [[Holocaust]] survivors became citizens of Israel, | + | While a large proportion of [[Holocaust]] survivors became citizens of Israel after [[World War II]], many Jews continued living where they had settled. Populations remain significant in the [[United States]], [[France]], [[Canada]], and the [[United Kingdom]]. Many diasporan Jews also continue to live in Russia and other former Soviet countries as well as in [[North Africa]], [[Iran]], [[South America]], [[India]], and even [[China]]. |

==Non-Jewish diasporas== | ==Non-Jewish diasporas== | ||

| − | The term diaspora can also be applied to various non-Jewish ethnic, national, or religious groups living away from their country of origin. The term carries a sense of displacement, as the population so described finds itself | + | The term ''diaspora'' can also be applied to various non-Jewish ethnic, national, or religious groups living away from their country of origin. The term carries a sense of displacement, as the population so described finds itself separated from its national territory. Often, such groups express a hope to return to their homeland at some point, or at least a sense of nostalgic connection to their place of origin. Colonizing migrations are not generally considered as diasporas, as migrants eventually assimilate into the settled area so completely that it becomes their new homeland. |

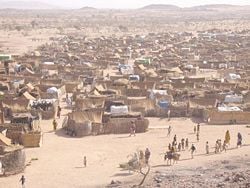

| + | [[Image:Darfur refugee camp in Chad.jpg|thumb|250 px|left|Refugee camp in [[Chad]] during the [[Darfur conflict]]]] | ||

| − | + | The twentieth century saw huge population movements, some due to [[natural disasters]], but many others involving large-scale transfers of people by government action. Major examples include the transfer of millions of people between [[India]] and [[Pakistan]] as a result the 1947 [[Partition of India]] and [[Stalin]]'s policy to populate Eastern [[Russia]], [[Central Asia]], and [[Siberia]]. Other diasporas have occurred as people fled ethnically directed persecution or oppression: for example, over a million [[Armenia]]ns forced out of Armenia by the Turks, many settling in Syria; European nationalities moving west away from the [[Soviet|Soviet Union]]'s [[annexation]] and from the [[Iron Curtain]] regimes after [[World War II]]; tens of thousands of [[South Asians]] expelled from [[Uganda]] by [[Idi Amin]] in 1975; and large numbers of [[Hutu]] and [[Tutsi]] escaping the [[Rwandan Genocide]] in 1994. | |

| − | + | During the [[Cold War]] era, huge populations of [[refugee]]s left various areas of conflict, especially from [[Third World]] nations. In [[South America]] thousands of [[Uruguay]]an refugees fled to [[Europe]] during the [[military junta|military rule]] of the 1970s and 1980s. In many [[Central America]] nations, [[Nicaraguan Diaspora|Nicaraguans]], [[El Salvador|Salvadorians]], [[Guatemala]]ns, [[Honduras|Hondurans]], [[Costa Rica]]ns, and [[Panama]]nians) were displaced by political conflicts. In the [[Middle East]], many [[Palestinians]] were forced to leave their homes to settle elsewhere and many [[Iranian people|Iranians]] fled the 1978 Islamic revolution). Large numbers of [[Africa]]ns have been dislocated by [[tribal war]]s, religious [[persecution]]s, and political strife. In [[Southeast Asia]], millions fled the onslaught of [[Communism]] in [[China]], [[Vietnam]], [[Cambodia]], and [[Laos]]. | |

| − | + | [[Economic migrants]] may gather in such numbers outside their home country that they, too, form an effective diaspora: for instance, the Turkish ''[[Gastarbeiter]]'' in Germany; South Asians in the Persian Gulf; and Filipinos and [[Overseas Chinese|Chinese]] throughout the world. And in a rare example of a diaspora within a prosperous Western democracy, there is talk of a [[New Orleans]], or [[Gulf Coast]], "diaspora" in the wake of [[Hurricane Katrina]] of 2005. | |

| − | + | ==Diasporan peoples and peace== | |

| + | While diasporan communities are sometimes criticized for promoting [[nationalism]] and [[extremism]], they also have been noted for contributing to peace efforts and broadening their homelands' attitudes. Such groups sometimes support pro-peace or pro-tolerance parties in their homelands, creating a more pluralistic culture.<ref>Bahar Baser and Ashok Swain, "Diasporas as Peacemakers: Third Party Mediation in Homeland Conflicts" ''International Journal on World Peace'' XXV (3) (September 2008).</ref> | ||

| − | + | Examples of diasporan groups fomenting [[nationalism]] or [[extremism]] include hardline factions in the communities of [[Ireland|Irish]], [[Tamil Tigers|Tamil]], [[Sikh]], [[Muslim]], and [[Kurds|Kurdish]] diasporas. On the other hand, diasporan groups have been instrumental in establishing dialog and building bridges between their host societies and their homelands, and have also played a positive role in domestic peacemaking. This phenomenon has been especially evident in western nations where diasporan peoples tend to interact with a more diverse population than they did in their home countries and sometimes adopt the pluralistic values of their host nations. Examples include [[Afghanistan|Afghan]], [[China|Chinese]], Irish, [[Iraq|Iraqi]], [[Jewish]], and [[Korea]]n groups, among others. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | + | * Baser, Bahar, and Ashok Swain. "Diasporas as Peacemakers: Third Party Mediation in Homeland Conflicts." ''International Journal on World Peace'' XXV (3) (September 2008) | |

| + | * Brenner, Frédéric. ''Diaspora: Homelands in Exile.'' New York: HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 978-0060087784 | ||

| + | * Collins, John Joseph. ''Between Athens and Jerusalem: Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Diaspora.'' New York: Crossroad, 1983. ISBN 978-0824504915 | ||

| + | * Francisco, Jason. ''Far from Zion: Jews, Diaspora, Memory.'' Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0804750455 | ||

| + | * Mishra, Sudesh. ''Diaspora Criticism.'' Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0748621064 | ||

| + | * Sachar, Howard Morley. ''Diaspora: An Inquiry into the Contemporary Jewish World.'' New York: Harper & Row, 1985. ISBN 978-0060154035 | ||

| + | * Sowell, Thomas. ''Migrations and Cultures: A World View.'' New York: BasicBooks, 1996. ISBN 978-0465045884 | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | * [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=329&letter=D | + | All links retrieved January 29, 2024. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | * [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=329&letter=D Diaspora at the JewishEncyclopedia.com] | |

| + | |||

[[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

[[Category:Religion]] | [[Category:Religion]] | ||

| + | [[category:history]] | ||

| + | [[category:Judaism]] | ||

{{credits|Diaspora|162391113}} | {{credits|Diaspora|162391113}} | ||

Latest revision as of 11:56, 29 January 2024

The term diaspora (in Ancient Greek, διασπορά – "a scattering or sowing of seeds") refers to any people or ethnic population forced or induced to leave its traditional homeland, as well as the dispersal of such people and the ensuing developments in their culture. It is especially used with reference to the Jews, who have lived most of their historical existence as a diasporan people.

The Jewish diaspora began with the conquests of the eighth to the sixth century B.C.E., when the Israelites were forcibly exiled first from the northern kingdom of Israel to Assyria and then from the southern kingdom of Judah to Babylon. Although some later returned to Judea, Jews continued to settle elsewhere during the periods of the Greek and Roman empires. Major centers of Jewish diasporan culture emerged in such places as Alexandria, Asia Minor, and Babylonia. A second major expulsion of Jews from the Holy Land took place as a result of destruction of the Second Temple in the wake of the Jewish Revolt of 70 C.E. and the subsequent Bar Kokhba revolt. From the mid-second century onward, diaspora was the normative experience of Jews until the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. The majority of Jews today are still a diasporan people.

Many other ethnic and religious groups also live in diaspora in the contemporary period as a result of wars, relocation programs, economic hardship, natural disasters, and political repression. Thus, it is common today to speak of an African diaspora, Muslim diaspora, Greek diaspora, Korean diaspora, Tibetan diaspora, etc. Diasporan peoples, by their exposure to other cultures, often play a role in broadening the outlook of their homeland populations, increasing the potential for pluralism and tolerance.

Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora (Hebrew: Tefutzah, "scattered," or Galut גלות, "exile") was the result of the expulsion of the Jews from the land of Israel, voluntary migrations, and, to a lesser extent, religious conversions to Judaism in lands other than Israel. The term was originally used by the Ancient Greeks to describe citizens of a dominant city-state who emigrated to a conquered land with the purpose of colonization, such as those who colonized Egypt and Syria. The earliest use of the word in reference specifically to Jewish exiles is in the Septuagint version of Deuteronomy 28:25: "Thou shalt be a dispersion in all kingdoms of the earth."

Pre-Roman diaspora

In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians under Shalmaneser V conquered the northern kingdom of Israel, and many Israelites were deported to the Assyrian province of Khorasan. Since then, for over 2700 years, the Persian Jews have lived in the territories of today's Iran.

After the overthrow in of the Kingdom of Judah by Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon and the subsequent deportation of a considerable portion of its inhabitants to Mesopotamia beginning in 588 B.C.E., the Jews had two principal cultural centers: Babylonia and the Judea. The more pious elements among the exiles returned to Judea during the Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.E.). With the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem as their center, they reorganized themselves into a community animated by a remarkable religious ardor and a tenacious attachment to the Torah, which thenceforth constituted the focus of Jewish identity.

Owing to internal dissensions in the Seleucid dynasty (312 - 63 B.C.E.) and to the support of the Romans, the cause of Jewish independence temporarily triumphed under the Hasmonean princes. The Jewish state prospered and even annexed several territories, but discord in the royal family and the growing disaffection of the religious elements made the Jewish nation an easy prey to the ambition of the growing Roman Empire. In 63 B.C.E., the military commander Pompey invaded Jerusalem, and the Jewish nation became a vassal of Rome.

The diaspora in Roman times

Jews were already widespread in the Roman Empire by the middle of the second century B.C.E., when the Jewish author of the third book of the Sibylline oracles, addressing the "chosen people," says: "Every land is full of thee and every sea." Diverse witnesses, such as Strabo, Philo, Seneca, Luke (the author of the Acts of the Apostles), Cicero, and Josephus, all mention Jewish populations in the cities of the Mediterranean.

Alexandria was by far the most important of the diasporan Jewish communities. Philo of Alexandria (d. 50 C.E.) gives the number of Jewish inhabitants in Egypt as one million, one-eighth of the population. Babylonia also had a very large Jewish population, as many Jews had never returned from there to Judea. The number of Jewish residents in Cyprus and in Mesopotamia was also large. It has been estimated that there were also about 180,000 Jews in Asia Minor in the year 62/61 B.C.E. In the city of Rome, at the commencement of the reign of Caesar Augustus, there were well over 7000 Jews.

King Agrippa I (d. 44 C.E.), in a letter to Caligula, enumerated communities of the Jewish diaspora in almost all the Hellenized and non-Hellenized countries of the Orient. According to the first-century Jewish historian Josephus, the Jewish population outside of Israel and Babylonia was densest in Syria, particularly in Antioch and Damascus. Some 10,000-18,000 Jews were reportedly massacred at Damascus during the Jewish Revolt of 70 C.E.; Jerusalem was destroyed, and Greek and Roman colonies were established in Judea to prevent the political regeneration of the Jewish nation. However, Jews sought to establish commonwealths in Cyrene, Cyprus, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. These efforts were suppressed by Trajan during the persecutions of 115-117. The attempt of the Jews of Palestine to regain their independence during the Bar Kochba revolt (132-135) was even more brutally crushed.

From this time on, the Jews of Palestine were greatly reduced in numbers, destitute, and crushed. As a result, they began to lose their preponderant influence in the Jewish world, and the center of spirituality shifted from the Jerusalem priesthood to the rabbinic tradition based in the local synagogues. Jerusalem, renamed as "Ælia Capitolina," had become a Roman colony, a city entirely pagan. Jews were forbidden entrance, under pain of death. Some, like Rabbi Akiva, suffered martyrdom as a result.

Nevertheless, in the sixth century there were 43 Jewish communities in Palestine, scattered along the coast, in the Negev, east of the Jordan, and in villages in the Galilee region, and in the Jordan River valley. Jewish communities expelled from Judea were sent, or decided to go, to various Roman provinces in the Middle East, Europe, and North Africa.

Post-Roman diaspora

Jews in the diaspora had been generally accepted into the Roman Empire, but with the rise of Christianity, restrictions against them grew. With the advent of Islam, Jews generally fared better in Muslim lands that Christian ones. The center of Jewish intellectual life thus shifted from Christian areas to Muslim Babylonia, which had already been developing a strong academic tradition at the great yeshivas of Sura and Pumpedita. These centers also developed the Babylonian Talmud, which came to be seen as more authoritative than its Palestinian counterpart as the key text of Jewish religious law and custom.

During the Middle Ages, Jews gradually moved into Europe, settling first in Muslim Spain and later in the Christian areas of the Rhineland. The Jewish diaspora thus divided into distinct regional groups which today are generally addressed according to two main divisions: the Ashkenazi (Northern and Eastern European Jews) and Sephardic Jews (Spanish and Middle Eastern Jews).

The Christian reconquest of Spain led ultimately to the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula beginning in the late fifteenth century. Many of these Sephardic Jews fled to Italy others the Netherlands and northern Europe, with still others going to the Middle East or Northern Africa. Meanwhile, the Ashkenazi population was growing rapidly. In 1764, there were about 750,000 Jews in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The worldwide Jewish population at that time is estimated at 1.2 million, mainly in Europe, Russia, and throughout the Ottoman Empire.

Expulsions, ghettoization, and pogroms haunted the Jews wherever they went in the Christian world, and the difficulty of Jewish life in the diaspora was a key factor in the advent of Zionism. Underlying this attitude was the feeling that the diaspora restricted the full growth of Jewish national life, coupled with the messianic current of Jewish religious thought, which looked to the Messiah as a Davidic descendant who will restore Jewish sovereignty in the Holy Land. The pogroms of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and the Holocaust of European Jews during WWII made many Jews feel that life in the diaspora could not be sustained without a Jewish state to which persecuted Jews could return if they desired.

Jewish diaspora today

The establishment of Israel as a Jewish state in 1948 meant that henceforth, living in the diaspora became a matter of choice rather than of necessity for many Jews. However, until the fall of Communism, Jews living in the former Soviet bloc were often forbidden to immigrate, while others faced economic obstacles.

While a large proportion of Holocaust survivors became citizens of Israel after World War II, many Jews continued living where they had settled. Populations remain significant in the United States, France, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Many diasporan Jews also continue to live in Russia and other former Soviet countries as well as in North Africa, Iran, South America, India, and even China.

Non-Jewish diasporas

The term diaspora can also be applied to various non-Jewish ethnic, national, or religious groups living away from their country of origin. The term carries a sense of displacement, as the population so described finds itself separated from its national territory. Often, such groups express a hope to return to their homeland at some point, or at least a sense of nostalgic connection to their place of origin. Colonizing migrations are not generally considered as diasporas, as migrants eventually assimilate into the settled area so completely that it becomes their new homeland.

The twentieth century saw huge population movements, some due to natural disasters, but many others involving large-scale transfers of people by government action. Major examples include the transfer of millions of people between India and Pakistan as a result the 1947 Partition of India and Stalin's policy to populate Eastern Russia, Central Asia, and Siberia. Other diasporas have occurred as people fled ethnically directed persecution or oppression: for example, over a million Armenians forced out of Armenia by the Turks, many settling in Syria; European nationalities moving west away from the Soviet Union's annexation and from the Iron Curtain regimes after World War II; tens of thousands of South Asians expelled from Uganda by Idi Amin in 1975; and large numbers of Hutu and Tutsi escaping the Rwandan Genocide in 1994.

During the Cold War era, huge populations of refugees left various areas of conflict, especially from Third World nations. In South America thousands of Uruguayan refugees fled to Europe during the military rule of the 1970s and 1980s. In many Central America nations, Nicaraguans, Salvadorians, Guatemalans, Hondurans, Costa Ricans, and Panamanians) were displaced by political conflicts. In the Middle East, many Palestinians were forced to leave their homes to settle elsewhere and many Iranians fled the 1978 Islamic revolution). Large numbers of Africans have been dislocated by tribal wars, religious persecutions, and political strife. In Southeast Asia, millions fled the onslaught of Communism in China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

Economic migrants may gather in such numbers outside their home country that they, too, form an effective diaspora: for instance, the Turkish Gastarbeiter in Germany; South Asians in the Persian Gulf; and Filipinos and Chinese throughout the world. And in a rare example of a diaspora within a prosperous Western democracy, there is talk of a New Orleans, or Gulf Coast, "diaspora" in the wake of Hurricane Katrina of 2005.

Diasporan peoples and peace

While diasporan communities are sometimes criticized for promoting nationalism and extremism, they also have been noted for contributing to peace efforts and broadening their homelands' attitudes. Such groups sometimes support pro-peace or pro-tolerance parties in their homelands, creating a more pluralistic culture.[1]

Examples of diasporan groups fomenting nationalism or extremism include hardline factions in the communities of Irish, Tamil, Sikh, Muslim, and Kurdish diasporas. On the other hand, diasporan groups have been instrumental in establishing dialog and building bridges between their host societies and their homelands, and have also played a positive role in domestic peacemaking. This phenomenon has been especially evident in western nations where diasporan peoples tend to interact with a more diverse population than they did in their home countries and sometimes adopt the pluralistic values of their host nations. Examples include Afghan, Chinese, Irish, Iraqi, Jewish, and Korean groups, among others.

Notes

- ↑ Bahar Baser and Ashok Swain, "Diasporas as Peacemakers: Third Party Mediation in Homeland Conflicts" International Journal on World Peace XXV (3) (September 2008).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baser, Bahar, and Ashok Swain. "Diasporas as Peacemakers: Third Party Mediation in Homeland Conflicts." International Journal on World Peace XXV (3) (September 2008)

- Brenner, Frédéric. Diaspora: Homelands in Exile. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 978-0060087784

- Collins, John Joseph. Between Athens and Jerusalem: Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Diaspora. New York: Crossroad, 1983. ISBN 978-0824504915

- Francisco, Jason. Far from Zion: Jews, Diaspora, Memory. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0804750455

- Mishra, Sudesh. Diaspora Criticism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0748621064

- Sachar, Howard Morley. Diaspora: An Inquiry into the Contemporary Jewish World. New York: Harper & Row, 1985. ISBN 978-0060154035

- Sowell, Thomas. Migrations and Cultures: A World View. New York: BasicBooks, 1996. ISBN 978-0465045884

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.