Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero (January 3, 106 B.C.E. ‚Äď December 7, 43 B.C.E.) Cicero was a Roman lawyer, statesman, philosopher and writer who lived during the most brilliant era of Roman public life. An academic skeptic and a Stoic, he devoted himself to applying philosophical theory to politics, with the aim of bringing about a better Roman Republic. He translated Greek works into Latin, and wrote Latin summaries of the teachings of the Greek philosophical schools, hoping to make them more accessible and understandable for Roman leaders. Many of Cicero‚Äôs original works are still in existence.

For Cicero, politics took precedence over philosophy. Most of his philosophical works were written at intervals when he was unable to participate in public life, and with the intent of influencing the political leaders of the time. He was elected to each of the principal Roman offices (quaestor, aedile, praetor, and consul) at the earliest legal age, and thus became a member of the Senate. He became deeply involved in the political conflicts of Rome, an involvement which led to his exile during 58-57 B.C.E. and finally to his death. Cicero was murdered at Formia on December 7, 43 B.C.E., while fleeing from his political enemies.

Life

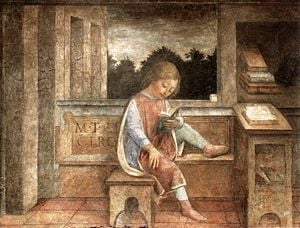

Many details of Cicero’s life are set down in a biography written by Plutarch about one hundred years after his death. Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in Arpinum in 106 B.C.E., the elder son of an aristocratic family. The name "Cicero" is derived from cicer, the Latin word for "chickpea." Plutarch explains that the name was originally applied to one of Cicero's ancestors who had a cleft in the tip of his nose, which resembled that of a chickpea. In his youth, Cicero, who was very ambitious and wanted to enter politics, moved to Rome to study law. He was a precocious student and attracted much attention. Cicero also made an extensive study of Greek philosophy, and considered himself both an academic skeptic and a Stoic. Cicero spent one year, 89-88 B.C.E., in the military, serving on the staffs of Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo and Lucius Cornelius Sulla during the Social War. In 75 B.C.E. Cicero served as quaestor in western Sicily where, he wrote, he saw the tombstone of Archimedes. He became a successful advocate, and first attained prominence for his successful prosecution in August of 70 B.C.E. of Gaius Verres, the former governor of Sicily.

In 63 B.C.E., Cicero became the first consul of Rome in more than thirty years whose family had not already served in the consulship. His only significant historical accomplishment during his year in office was the suppression of the Catiline conspiracy, a plot to overthrow the Roman Republic led by Lucius Sergius Catilina, a disaffected patrician. According to Cicero‚Äôs own account, he procured a senatus consultum de re publica defendenda (a declaration of martial law) and drove Catiline out of the city by giving four vehement speeches in the Senate. Catiline fled to Etruria, but left behind some ‚Äúdeputies‚ÄĚ to start a revolution in Rome, while he attacked with any army raised from among Sulla‚Äôs veterans. Cicero engineered a confession by these ‚Äúdeputies‚ÄĚ before the entire Senate.

The Senate then deliberated upon the punishment to be given to the conspirators. As it was a legislative rather than a judicial body, its powers were limited; however, martial law was in effect, and it was feared that simple house arrest or exile would not remove the threat that the conspirators presented to the State. At first, most in the Senate spoke for the 'extreme penalty'; many were then swayed by Julius Caesar who decried the precedent it would set and argued in favor of the punishment being confined to a mode of banishment. Cato then rose in defense of the death penalty and all the Senate finally agreed on the matter. Cicero had the conspirators taken to the Tullianum, the notorious Roman prison, where they were hanged. After the executions had been carried out, Cicero announced the deaths by the formulaic expression "They have lived," meant to ward off ill fortune by avoiding the direct mention of death. He received the honorific Pater Patriae (‚ÄúFather of the Nation‚ÄĚ) for his actions in suppressing the conspiracy, but thereafter lived in fear of trial or exile for having put Roman citizens to death without trial. He was also accorded the first public thanksgiving, which had previously been only a military honor, for a civic accomplishment.

In 60 B.C.E. Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus formed the First Triumvirate and took control of Roman politics. They made several attempts to elicit the support of Cicero, but he eventually refused, preferring to remain loyal to the Senate and the idea of the Republic. This left him vulnerable to his enemies. In 58 B.C.E., the populist Publius Clodius Pulcher proposed a law exiling any man who had put Roman citizens to death without trial. Although Cicero maintained that the sweeping senatus consultum ultimum granted him in 63 B.C.E. had indemnified him against legal penalty, he felt threatened by Clodius and left Italy. The law passed, and all Cicero’s property was confiscated. Cicero spent over a year in exile. During this time he devoted himself to philosophical studies and writing down his speeches.

The political climate changed and Cicero returned to Rome, greeted by a cheering crowd. Cicero supported the populist Milo against Clodius, and around 55 B.C.E., Clodius was killed by Milo‚Äôs gladiators on the Via Appia. Cicero conducted Milo‚Äôs legal defense, and his speech Pro Milone is considered by some as his ultimate masterpiece. The defense failed, and Milo fled into exile. Between 55 and 51 B.C.E. Cicero, still unable to participate actively in politics, wrote On the Orator, On the Republic, and On the Laws. The Triumvirate collapsed with the death of Crassus and in 49 B.C.E., and Caesar crossed the Rubicon River, entering Italy with his army and igniting a civil war between himself and Pompey. Cicero favored Pompey but tried to avoid turning Caesar into a permanent enemy. When Caesar invaded Italy in 49 B.C.E., Cicero fled Rome. Caesar attempted vainly to convince him to return, and in June of that year Cicero slipped out of Italy and traveled to Dyrrachium (Epidamnos). In 48 B.C.E., Cicero was with the Pompeians at the camp of Pharsalus and quarreled with many of the Republican commanders, including a son of Pompey. They in turn disgusted him by their bloody attitudes. He returned to Rome, after Caesar's victory at Pharsalus. In a letter to Varro on April 20, 46 B.C.E., Cicero indicated what he saw as his role under the dictatorship of Caesar: "I advise you to do what I am advising myself ‚Äď avoid being seen, even if we cannot avoid being talked about... If our voices are no longer heard in the Senate and in the Forum, let us follow the example of the ancient sages and serve our country through our writings, concentrating on questions of ethics and constitutional law."

In February 45 B.C.E., Cicero's daughter Tullia died. He never entirely recovered from this shock.

Cicero was taken completely by surprise when the Liberatores assassinated Caesar on the Ides of March 44 B.C.E. In a letter to the conspirator Trebonius, Cicero expressed a wish of having been "...invited to that superb banquet." Cicero saw the political instability as an opportunity to restore the Republic and the power of the Senate. Cicero made it clear that he felt Mark Antony, who was consul and executor of Caesar’s will, was taking unfair liberties in interpreting Caesar's wishes and intentions.

When Octavian, Caesar's heir, arrived in Italy in April, Cicero formed a plan to set him against Antony. In September he began attacking Antony in a series of speeches, which he called the Philippics, before the Senate. Praising Octavian to the skies, he labeled him a "God-Sent Child" and said he only desired honor and that he would not make the same mistake as his Uncle. Cicero rallied the Senate in firm opposition to Antony. During this time, Cicero became an unrivaled popular leader and, according to the historian Appian, "had the power any popular leader could possibly have." Cicero supported Marcus Junius Brutus as governor of Cisalpine Gaul (Gallia Cisalpina) and urged the Senate to name Antony an enemy of the state. The speech of Lucius Piso, Caesar's father-in-law, delayed proceedings against Antony, but he was later declared an enemy of the state when he refused to lift the siege of Mutina, which was in the hands of one of Caesar's assassins, Decimus Brutus.

Cicero’s plan to drive out Mark Antony and eventually Octavian failed when the two reconciled and allied with Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate. Immediately after legislating their alliance into official existence for a five-year term with consular imperium, the Triumviri began proscribing their enemies and potential rivals. Cicero and his younger brother Quintus Tullius Cicero, formerly one of Caesar's legates, and all of their contacts and supporters were numbered among the enemies of the state. Mark Antony set about to assassinate all of his enemies. Cicero, his brother and nephew decided belatedly to flee and were captured and killed on December 7, 43 B.C.E. Plutarch describes the end of Cicero's life: "Cicero heard [his pursuers] coming and ordered his servants to set the litter [in which he was being carried] down where they were. He…looked steadfastly at his murderers. He was all covered in dust; his hair was long and disordered, and his face was pinched and wasted with his anxieties - so that most of those who stood by covered their faces while Herennius was killing him. His throat was cut as he stretched his neck out from the litter….By Antony's orders Herennius cut off his head and his hands." Cicero’s last words were said to have been "there is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly." His head and hands were displayed on the Rostra in the Forum Romanum; he was the only victim of the Triumvirate's proscriptions to have been so displayed after death. According to Cassius Dio (often mistakenly attributed to Plutarch), Antony's wife Fulvia took Cicero's head, pulled out his tongue, and jabbed the tongue repeatedly with her hairpin, taking a final revenge against Cicero's power of speech.

Cicero's son, also named Marcus, who was in Greece at this time, was not executed. He became consul in 30 B.C.E. under Octavian, who had defeated Antony after the Second Triumvirate collapsed.

Cicero's memory survived long after his death and the death of the Roman republic. The early Catholic Church declared him a "Righteous Pagan," and therefore many of his works were deemed worthy of preservation. Saint Augustine and others quoted liberally from his works The Republic and The Laws, and it is from these fragments that much of these works has been recreated.

Another story of his fame also shows may suffice as well: Caesar's heir Octavian became Augustus, Rome's first emperor, and it is said that in his later life he came upon one of his grandsons reading a book by Cicero. The boy, fearing his grandfather's reaction, tried to hide the book in the folds of his tunic. Augustus saw this, however, and took the book from him, standing as he read the greater part of it. He then handed the volume back to his grandson with the words "he was a learned man, dear child, a learned man who loved his country."

Thought and Works

Cicero made several significant contributions to the development of modern Western thought. He not only wrote about Stoic ethics, but also made a sincere effort to apply them in the political life of Rome. Cicero loved Greece, and even stated in his will that he wanted to be buried there. His works ensured that the thought of the Greek philosophers was known not only to Roman academics, but also to all literate Romans. When translating the concepts of Greek philosophers into Latin, he invented new Latin words which became the roots for English words, including ‚Äúmorals,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúproperty,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúindividual,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúscience,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúimage,‚ÄĚ and ‚Äúappetite.‚ÄĚ He summarized in Latin the beliefs of each of the primary Greek schools of philosophy, including the Academic Skeptics, Stoics, Peripatetics, and Epicureans, preserving details of their thought systems for future scholars. Most of the works of the early Greek philosophers were lost, perhaps even deliberately destroyed by the early Christians, but Cicero‚Äôs writings remained as a valuable source for Medieval and Renaissance scholars. His works were an essential part of the education of the eighteenth century Americans who participated in the creation of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.

Of Cicero’s works, more than 50 speeches, 12 works on philosophical topics, several works on rhetorical theory, and over 900 letters written or received by him are still in existence.

Skepticism and Stoicism

Cicero studied with both the Old and the New Academies of the Skeptics, both of which claimed to be descended from the First Academy established by Plato. The Skeptics believed that human beings could never be certain in their knowledge of the world, and therefore no philosophy could be said to be true. Any belief was subject to change if a better argument presented itself. Cicero frequently used dialogue in his works, enabling him to voice several arguments at once by putting them in the mouths of different speakers, thus allowing the reader to judge the accuracy of each viewpoint.

For ethics and morals, Cicero turned to Stoicism, saying, in the Laws, that it was dangerous for people not to believe completely in the sanctity of laws and of justice. He offered Stoic doctrines as the best available code of ethics, to be adhered to because doing so would make everyone’s lives better. His greatest interest was in the application of Stoic ethics to justice, and in the concept of duty, as required by a person’s public office and social standing. Cicero felt that the political aristocracy of his time had become corrupt and no longer possessed the virtuous character of earlier Roman leaders, and that this had caused the Roman republic to fall into difficulties. He hoped that philosophical guidance would motivate the Roman elite to value individual virtue and social stability above fame, wealth and power, and that they would then enact legislation to impose the same standards on the Romans in general. In this way, he felt that the Roman republic could be restored to its previous glory. Cicero favored Rome as the imperial power that could bring political stability to surrounding states.

Epicureanism

Cicero’s disdain for Epicureanism led him to severe criticism and even misrepresentation of Epicurean doctrines. Nevertheless, his writings contain numerous quotes and references to Epicurus’ works, which made it possible for scholars to piece together details of Epicurean doctrine when the original written works of Epicurus were lost. Cicero’s good friend Atticus, to whom many of his letters were written, was an Epicurean. Cicero criticized the Epicurean tendency to withdraw from politics and public life. During his forced exile from politics, however, Cicero wrote in some of his letters that he had become an Epicurean, since all that was left to him was to cultivate private life and its pleasures.

Written Works

Cicero’s written works can be divided into three types: his philosophic works, speeches, and about nine hundred letters.

Many of his philosophical writings were patterned after Plato's or Aristotle's dialogues. They include, in chronological order, On Invention, On the Orator, On the Republic, On the Laws, Brutus, Stoic Paradoxes, The Orator, Consolation, Hortensius, Academics, On Ends, Tusculan Disputations, On the Nature of the Gods, On Divination, On Fate, On Old Age, On Friendship, Topics, On Glory, and On Duties. Several of these have been almost entirely lost (Hortensius; On the Value of Philosophy; the Consolation, which Cicero wrote to himself on the death of his beloved daughter Tullia in order to overcome his grief; and On Glory). Only fragments exist of several of the others (notably the Laws, which Cicero may never have finished, and the Republic, fragments of which were only discovered in 1820 in the Vatican). Most of these works were written with a political aim in mind and not solely as philosophical discourses.

About 60 of the speeches made by Cicero as a lawyer and as a Senator remain. They provide insights into Roman cultural, political, social, and intellectual life; glimpses of Cicero's philosophy, and descriptions of the corruption and immorality of the Roman elite. Some of the speeches were never delivered in public, and many were written down and polished during the periods when Cicero was not active in politics.

More than nine hundred letters written by Cicero, or to him, have been preserved. Most of them were addressed to his close friend Atticus or his brother Quintius, but some are correspondence with other Romans, including Caesar. The letters contain references to the mundane calculations, compromises, flatteries, and manipulations of contemporary Roman politics.

On the Orator

On the Orator is dialogue on the ideal orator which contains useful discussions of the nature of law, philosophy and rhetoric, and the relationships among them. Cicero gives rhetoric more importance than law and philosophy, arguing that the ideal orator would have mastered both and would add eloquence besides. He regrets that philosophy and rhetoric are no longer taught together, as they were in the old days. He suggests that the best orator is also be the best human being, understanding the correct way to live, acting upon it by taking an active role in politics, and instructing others through speeches, through his example, and through making good laws.

On the Republic

Only fragments remain of this dialogue, which describes the ideal commonwealth. Set in 129 B.C.E., a few years before Cicero’s birth, it suggests that Roman history has resulted in the increasing perfection of the Roman republic, which is now superior to any other government because it balances elements of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. The dialogue suggests that this government is now being undermined by the moral decay of the aristocracy and is in danger of destroying itself. Cicero emphasizes the importance of a life of virtue, and explains the role of a statesman, the concept of natural law and the foundations of community. This work includes the famous Dream of Scipio.

On the Laws

This dialogue is fragmentary, and may never have been finished. Cicero proposes laws for an ideal commonwealth. In order to discover true law and justice, he says that we must examine "…what nature has given to humans; what a quantity of wonderful things the human mind embraces; for the sake of performing and fulfilling what function we are born and brought into the world; what serves to unite people; and what natural bond there is between them." Philosophy and reason must be used to discover the principles of justice, and to create laws. Any valid law must come from natural law. Both the gods and humans are endowed with reason; therefore they are part of the same universal community. The gods dispense their own justice, caring for us, and punishing and rewarding us as appropriate.

Brutus

This work contains a history of oratory in Greece and Rome, listing hundreds of orators and their distinguishing characteristics, weaknesses as well as strengths. Cicero discusses the role of an orator and the characteristics of a good orator. An orator must be learned in philosophy, history, and must "instruct his listener, give him pleasure, [and] stir his emotions." A good orator is by nature qualified to lead in government. Cicero says that orators must be allowed to "distort history in order to give more point to their narrative."

Stoic Paradoxes

Cicero discusses six Stoic paradoxes: moral worth is the only good; virtue is sufficient for happiness; all sins and virtues are equal; every fool is insane; only the wise man is really free; only the wise man is really rich. Although he claims that he is simply translating Stoic principles into plain speech for his own amusement, Stoic Paradoxes illustrates Cicero’s rhetorical skills and is a thinly veiled attack on his enemies.

The Orator

This is a letter written in defense of Cicero’s own style of oratory. It describes the qualities of a good orator, who must be able to persuade his audience, entertain them and arouse their emotions. It includes a famous quote "To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child."

Hortensius

Much of this text has been lost, but St. Augustine credits it with turning him to a life of introspection and philosophy. It is a treatise praising philosophy, and explaining how true happiness can only be attained by using it to develop reason and overcome passion.

Academics

This dialogue explains and challenges the epistemology of each of the philosophical schools, and questions whether truth can actually be known. Cicero leaves the reader to decide which argument is most correct. The dialogue includes a detailed history of the development of the schools of philosophy after the death of Socrates. The explanations included in this work have been invaluable to scholars of early Greek philosophers, whose original writings were lost.

On Ends

This dialogue sets out the beliefs of several schools of philosophy on the question of the end, or purpose of human life. "What is the end, the final and ultimate aim, which gives the standard for all principles of right living and of good conduct?" The work was intended to educate Romans about Greek philosophy.

Tusculan Disputations

The first two books present and then refute the ideas that death and pain are evils. The third book demonstrates that a wise man will not suffer from anxiety and fear, the fourth book that a wise man does not suffer from excessive joy or lust. The fifth and final book suggests that virtue is sufficient for a happy life. This work was intended to educate the Romans and to show that the Roman people and the Roman language were capable of arriving at the highest levels of philosophy.

On the Nature of the Gods, On Divination, On Fate

These three dialogues were intended to be a trilogy on religious questions. On the Nature of Gods gives descriptions of dozens of varieties of religion. The Epicurean view that the gods exist but are indifferent about human beings; and the Stoic view that the gods love human beings, govern the world and dispense justice after death, are both stated and refuted. The dialogue does not reach a conclusion. On Divination presents both sides of the idea that the future can be predicted through divination (astrology, reading animal entrails, etc.). Unwise political decision was prevented by the announcement that the omens were unfavorable. On Fate discusses free will and causation, and deals with the meaning of truth and falsehood.

On Old Age

This dialogue discusses our attitude towards infirmity and the approach of death. Cicero explains that old age and death are a natural part of life and should be accepted calmly. As he ages, a man of good character will enjoy pleasant memories of a good life, prestige and intellectual pleasures. A man of bad character will only become more miserable as he ages.

On Friendship

This is a dialogue examining the nature of true friendship, which is based on virtue and does not seek material advantage. It arrives at the conclusion that the entire cosmos, including gods and men, is bonded in a community based on reason. Cicero speaks of the difficulties of maintaining friendships in the real world, where there is adversity and political pressure. He also expresses the idea that deeds are better than words.

On Duties

A letter addressed to his son Marcus, then in his late teens and studying philosophy in Athens, this work contains the essence of Cicero’s philosophical thought. It explains how the end, or ultimate purpose of life, defines our duties and the ways in which we should perform them. The letter discusses how to choose between the honorable and the expedient, and explains that the two are never in conflict if we have a true understanding of duty.

Speeches

Of his speeches, 88 were recorded, but only 58 survive (some of the items below are more than one speech).

Italic text Judicial speeches

- (81 B.C.E.) Pro Quinctio (On behalf of Publius Quinctius)

- (80 B.C.E.) Pro Sex. Roscio Amerino (On behalf of Sextus Roscius of Ameria)

- (77 B.C.E.) Pro Q. Roscio Comoedo (On behalf of Quintus Roscius the Actor)

- (70 B.C.E.) Divinatio in Caecilium (Spoken against Caecilius at the inquiry concerning the prosecution of Verres)

- (70 B.C.E.) In Verrem (Against Gaius Verres, or The Verrines)

- (69 B.C.E.) Pro Tullio (On behalf of Tullius)

- (69 B.C.E.) Pro Fonteio (On behalf of Marcus Fonteius)

- (69 B.C.E.) Pro Caecina (On behalf of Aulus Caecina)

- (66 B.C.E.) Pro Cluentio (On behalf of Aulus Cluentius)

- (63 B.C.E.) Pro Rabirio Perduellionis Reo (On behalf of Rabirius on a Charge of Treason)

- (63 B.C.E.) Pro Murena (On behalf of Lucius Murena)

- (62 B.C.E.) Pro Sulla (On behalf of Sulla)

- (62 B.C.E.) Pro Archia Poeta (On behalf of the poet Archias)

- (59 B.C.E.) Pro Flacco (On behalf of Flaccus)

- (56 B.C.E.) Pro Sestio (On behalf of Sestius)

- (56 B.C.E.) In Vatinium (Against Vatinius at the trial of Sestius)

- (56 B.C.E.) Pro Caelio (On behalf of Marcus Caelius Rufus)

- (56 B.C.E.) Pro Balbo (On behalf of Cornelius Balbus)

- (54 B.C.E.) Pro Plancio (On behalf of Plancius)

- (54 B.C.E.) Pro Rabirio Postumo (On behalf of Rabirius Postumus)

Political speeches

- Early career (before exile)

- (66 B.C.E.) Pro Lege Manilia or De Imperio Cn. Pompei (in favor of the Manilian Law on the command of Pompey )

- (63 B.C.E.) De Lege Agraria contra Rullum (Opposing the Agrarian Law proposed by Rullus )

- (63 B.C.E.) In Catilinam I-IV ( Catiline Orations or Against Catiline )

- ( 59 B.C.E. ) Pro Flacco (In Defense of Flaccus)

- Mid career (after exile)

- (57 B.C.E.) Post Reditum in Quirites (To the Citizens after his recall from exile)

- (57 B.C.E.) Post Reditum in Senatu (To the Roman Senate|Senate after his recall from exile)

- (57 B.C.E.) De Domo Sua (On his House)

- (57 B.C.E.) De Haruspicum Responsis (On the Responses of the Haruspices )

- (56 B.C.E.) De Provinciis Consularibus (On the Consular Provinces)

- (55 B.C.E.) In Pisonem (Against Piso )

- Late career

- ( 52 B.C.E. ) Pro Milone (On behalf of Titus Annius Milo )

- ( 46 B.C.E. ) Pro Marcello (On behalf of Marcus Claudius Marcellus|Marcellus )

- (46 B.C.E.) Pro Ligario (On behalf of Ligarius before Caesar)

- (46 B.C.E.) Pro Rege Deiotaro (On behalf of King Deiotarus before Caesar)

- ( 44 B.C.E. ) Philippicae (consisting of the 14 philippic s Philippica I-XIV against Marc Antony|Marcus Antonius )

(The Pro Marcello, Pro Ligario, and Pro Rege Deiotaro are collectively known as "The Caesarian speeches").

Philosophy

Rhetoric

- ( 84 B.C.E. ) De Inventione (About the composition of arguments)

- ( 55 B.C.E. ) De Oratore (About oratory)

- ( 54 B.C.E. ) De Partitionibus Oratoriae (About the subdivisions of oratory)

- ( 52 B.C.E. ) De Optimo Genere Oratorum (About the Best Kind of Orators)

- (46 B.C.E.) Brutus (Cicero)|Brutus (For Brutus, a short history of Roman oratory dedicated to Marcus Junius Brutus)

- (46 B.C.E.) Orator ad M. Brutum (About the Orator, also dedicated to Brutus)

- (44 B.C.E.) Topica (Topics of argumentation)

- (?? B.C.E.) Rhetorica ad Herennium (traditionally attributed to Cicero, but currently disputed)

Other philosophical works

- ( 51 B.C.E. ) De Republica (On the Republic)

- ( 45 B.C.E. ) Hortensius (Hortensius)

- (45 B.C.E.) Lucullus or Academica Priora (The Prior Academics)

- (45 B.C.E.) Academica Posteriora (The Later Academics)

- (45 B.C.E.) De Finibus, Bonorum et Malorum (About the Ends of Goods and Evils). Source of Lorem ipsum

- (45 B.C.E.) Tusculanae Quaestiones (Questions debated at Tusculum)

- (45 B.C.E.) De Natura Deorum (The Nature of the Gods)

- (45 B.C.E.) De Divinatione (Divination)

- (45 B.C.E.) De Fato (The Fate)

- (44 B.C.E.) Cato Maior de Senectute (Cato the Elder On Old Age )

- (44 B.C.E.) Laelius de Amicitia (Laelius On Friendship )

- (44 B.C.E.) De Officiis (Duties)

- (?? B.C.E.) Paradoxa Stoicorum (Stoic Paradoxes)

- (?? B.C.E.) De Legibus (The Laws)

- (?? B.C.E.) De Consulatu Suo (His Consulship)

- (?? B.C.E.) De temporibus suis (His Life and Times)

- (?? B.C.E.) Commentariolum Petitionis (Handbook of Candidacy) (attributed to Cicero, but probably written by his brother Quintus)

Letters

More than 800 letters by Cicero to others exist, and over 100 letters from others to him.

- ( 68 B.C.E. - 43 B.C.E. ) Epistulae ad Atticum (Letters to Atticus)

- ( 59 B.C.E. - 54 B.C.E. ) Epistulae ad Quintum Fratrem (Letters to his brother Quintus)

- ( 43 B.C.E. ) Epistulae ad Brutum (Letters to Brutus)

- (43 B.C.E.) Epistulae ad Familiares (Letters to his friends)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anthony, Everitt. 2001. Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome's Greatest Politician. Reprint edition, 2003. New York: Random House. ISBN 037575895X

- Fuhrmann, Manfred. 1990. Cicero and the Roman Republic. Paperback edition, 1996. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0631200118

- Gaius Sallustius Crispus, trans. Rev. John Selby Watson. 1867. Conspiracy of Catiline. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Habicht, Christian. 1989. Cicero the Politican. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 080183872X

- Mitchell, Thomas. 1979. Cicero, the Ascending Years. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300022778

- Mitchell, Thomas. 1991.Cicero the Senior Statesman. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300047797

- Moles, J. L. 1989. Plutarch: Life of Cicero. Oxford: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 0856683612

- Shackleton Bailey, D.R. (ed.). 2002. Cicero, Letters to Quintus and Brutus/Letter Fragments/Letter to Octavian/Invectives Handbook of Electioneering (Loeb Classical Library). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674995996

- Smith, R. E. 1966. Cicero the Statesman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521065011

- Taylor, H. 1918. Cicero: A sketch of his life and works. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co.

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- Cicero in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Dryden's translation of Cicero from Plutarch's Parallel Lives

- Works by Cicero:

- Perseus Project (Latin and English): Cicero

- The Latin Library (Latin): Works of Cicero

- Biographies and descriptions of Cicero's time at Project Gutenberg

- Plutarch's biography of Cicero contained in the Parallel Lives

- Life of Cicero by Anthony Trollope, Volume I

- Cicero by Rev. W. Lucas Collins (Ancient Classics for English Readers)

- Roman life in the days of Cicero by Rev. Alfred J. Church

- Social life at Rome in the Age of Cicero by

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.