Napoleon III

| Napoléon III | ||

|---|---|---|

| Emperor of the French | ||

| ||

| Portrait by Franz Winterhalter | ||

| Reign | December 2, 1852 â September 4, 1870 | |

| Full name | Charles Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte | |

| Born | April 20 1808 | |

| Paris, France | ||

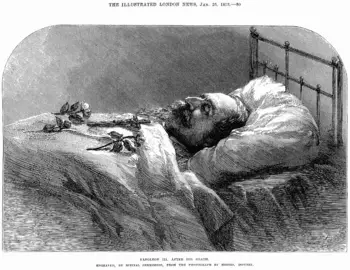

| Died | 9 January 1873 (aged 64) | |

| Chislehurst | ||

| Buried | St Michael's Abbey, Farnborough | |

| Predecessor | De Facto, Louis EugĂšne Cavaignac (as Head of State) De Jure, Louis Bonaparte | |

| Successor | Empire abolished De Facto Louis Jules Trochu as Chairman of the Government of National Defense De Jure, Napoleon IV | |

| Consort | MarĂa Eugenia Ignacia Agustina Guzman y Montijo | |

| Issue | Napoleon Eugene, Prince Imperial | |

| Royal House | Bonaparte | |

| Father | Louis Bonaparte | |

| Mother | Hortense de Beauharnais | |

NapolĂ©on III, also known as Louis-NapolĂ©on Bonaparte (full name Charles Louis-NapolĂ©on Bonaparte) (April 20, 1808 â January 9, 1873) was the first President of the French Republic and the only emperor of the Second French Empire. He holds the unusual distinction of being both the first titular president and the last monarch of France. He was the nephew of Napoleon I and a cousin of Napoleon II, whose claim to be emperor was only ever really recognized by Bonapartists. However, when Louis-Napoleon became emperor in 1852, he legitimized his cousinâs reign by taking the designation âIII.â After several failed attempts to gain power by extra-constitutional means, it was by winning a landslide electoral victory that Louis-Napoleon became President in 1848. In 1851, frustrated because he could not stand for re-election, he manipulated the system to become Emperor. He then exercised dictatorial powers, while maintaining the fiction of democratic governance. Initially, his regime was authoritarian brooking no criticism or opposition. Later, he was described as a âliberalâ and even as a âsocialistâ because some of his policies showed genuine concern for the public good. On the one hand, he led France into several disastrous foreign engagements especially the Franco-Prussian War. For some, this darkens his reputation. On the other hand, he expanded Franceâs colonial possessions and, in choosing to fight on the winning side in the Crimean War realigned Franceâs relationship with Great Britain, which proved vital for the nationâs survival in the twentieth century. On two occasions, this cross-channel alliance helped to save France from annexation by Germany, ensuring that it continues to play a role in world affairs.

Napoleon IIIâs ambivalent relationship with democracy may not have been solely due to his own moral failings. The leaders and the people of Post-revolutionary France lacked a shared vision of how society ought to be governed, and oscillated between republican and monarchist systems. The revolution violently toppled an unjust, totalitarian system in the name of brotherhood, equality and freedom but had no thought through alternative to replace this with. Napoleon III has suffered from comparison with Napoleon I, whose life ended in defeat but who is credited nonetheless with military and administrative genius.

Early life

Napoléon III was the son of Louis Bonaparte, the brother of Napoléon I, and Hortense de Beauharnais, the daughter of Napoléon I's wife Josephine de Beauharnais by her first marriage. During Napoléon I's reign, Louis-Napoléon's parents had been made king and queen of a French puppet state, the Kingdom of Holland. After Napoléon I's final defeat and deposition in 1815 and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in France, all members of the Bonaparte dynasty were forced into exile, so the child Louis-Napoléon was brought up in Switzerland (living with his mother in the canton of Thurgau) and Germany (receiving his education at the gymnasium school at Augsburg in Bavaria). As a young man he settled in Italy, where he and his elder brother Napoléon Louis espoused liberal politics and became involved in the Carbonari, a resistance organization fighting Austria's domination of Northern Italy. This would later have an effect on his foreign policy.

In France, a Bonapartist movement continued to aspire to restore a member of Napoleonâs family to the throne. According to the law of succession NapolĂ©on I had made when he was Emperor, the claim passed first to his son, the Napoleon II, who was briefly acknowledged as Emperor at least by the Bonapartists but lived for most of his life under virtual imprisonment in Vienna, then to his eldest brother Joseph Bonaparte, then to Louis Bonaparte and his sons. Joseph's elder brother Lucien Bonaparte and his descendants were passed over by the law of succession because Lucien had opposed NapolĂ©on I, making himself Emperor. Since Joseph had no male children and because Louis-NapolĂ©on's own elder brother had died in 1831, Napoleon IIâs death in 1832 made Louis-NapolĂ©on the Bonaparte heir-presumptive in the next generation. His uncle and father, relatively old men by then, left to him the active leadership of the Bonapartist cause.

In October 1836, for the first time since his childhood, he re-entered France to try to lead a Bonapartist coup at Strasbourg. Louis-Philippe had established the July Monarchy in 1830, and was confronted with opposition both from the Legitimists, the Independents and the Bonapartists. The coup failed; he was illegally deported to Lorient and silently exiled to the United States of America, where he four years in New York. In August 1840, he launched a second bid for power, this time sailing with some hired soldiers into Boulogne. He was caught and sentenced to life imprisonment, though in relative comfort, in the fortress of the town of Ham in the Department of Somme. While in the Ham fortress, sight began to fail. During his years of imprisonment, he wrote essays and pamphlets that combined his monarchical claim with progressive, even mildly socialist economic proposals, as he defined Bonapartism. In 1844, his uncle Joseph died, which made him the direct heir apparent to the Bonaparte claim. In May 1846 he managed to escape to England by changing clothes with a mason working at the fortress. His enemies would later derisively nickname him "Badinguet," the name of the mason whose identity he assumed. A month later, his father Louis was dead, making Louis-Napoléon the clear Bonapartist candidate to rule France.

President of the French Republic

Louis-Napoléon stayed in the United Kingdom until the revolution of February 1848 in France deposed Louis-Philippe and established a Republic. He was now free to return to France, which he immediately did. He ran for and won a seat in the assembly elected to draft a new constitution but did not make a great contribution and, as a mediocre public orator, failed to impress his fellow members. Some even thought that, having lived outside of France almost all his life, he spoke French with a slight foreign accent.

However, when the constitution of the Second Republic was finally promulgated and direct elections for the presidency were held on December 19, 1848, Louis-NapolĂ©on won a surprising landslide victory, with 5,587,759 votes (around 75 percent of the total); his closest rival, Louis-EugĂšne Cavaignac, received only 1,474,687 votes. Louis-Napoleon had no long political career behind him and was able to depict himself as "all things to some men." The monarchist right (supporters of either the Bourbon or Orleanist royal households) and much of the upper class supported him as the "least worst" candidate, as a man who would restore order, end the instability in France which had continued since the overthrow of the monarchy in February, and prevent a proto-communist revolution (in the vein of Friedrich Engels). His vague indications of progressive economic views won over a good proportion of the industrial working. His overwhelming victory was above all due to the support of the non-politicized rural masses. For them, the name âBonaparteâ meant something, as opposed to the names of other, little-known contenders. Louis-NapolĂ©on's platform was the restoration of order after months of political turmoil, strong government and social consolidation, to which he appealed with all the credit of his name, that of France's national hero, NapolĂ©on I, who in popular memory was credited with raising the nation to its pinnacle of military greatness and establishing social stability after the turmoil of the French Revolution. During his term as President, Louis-NapolĂ©on Bonaparte was commonly called the Prince-President (Le Prince-PrĂ©sident).

Despite his landslide victory, Louis-Napoléon was faced with a Parliament dominated by monarchists, who saw his government only as a temporary bridge to a restoration of either the House of Bourbon or of Orléans. Louis-Napoleon governed cautiously during his first years in office, choosing his ministers from among the more "centre-right" Orleanist monarchists, and generally avoiding conflict with the conservative assembly. He courted Catholic support by assisting in the restoration of the Pope's temporal rule in Rome, although he tried to please secularist conservative opinion at the same time by combining this with peremptory demands that the Pope introduce liberal changes to the government of the Papal States, including appointing a liberal government and establishing the Code Napoleon there, which angered the Catholic majority in the assembly. He soon made another attempt to gain Catholic support, however, by approving the Loi Falloux in 1851, which restored a greater role for the Church in the French educational system.

In the third year of his four-year mandate, President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte asked the National Assembly for a revision of the constitution to enable the president to run for re-election, arguing that four years were not enough to implement his political and economic program fully. The Constitution of the Second Republic stated that the Presidency of the Republic was to be held for a single term of four years, with no possibility of re-election, a restriction written in the Constitution for fear that a President would abuse his power to transform the Republic into a dictatorship with a president for life. The National Assembly, dominated by monarchists who wished to restore the Bourbon dynasty, refused to amend the Constitution. The National Assembly had also changed the electoral law to place restrictions on universal male suffrage, imposing a three-year residency requirement which would have prevented the large proportion of the lower class, which was itinerant, from voting. Although he had originally acquiesced to this law, Louis-Napoleon used it as a pretext to break with the Assembly and his conservative ministers. He surrounded himself with lieutenants completely loyal to him, such as Morny and Persigny, secured the support of the army, and toured the country making populist speeches condemning the assembly and presenting himself as the protector of universal male suffrage.

After months of stalemate, and using the money of his mistress, Harriet Howard, he staged a coup d'état and seized dictatorial powers on December 2, 1851, the 47th anniversary of Napoléon I's crowning as Emperor, and also the 46th anniversary of the famous Battle of Austerlitz (hence another of Louis-Napoleon's nicknames: "The Man of December," "l'homme de décembre"). The coup was later declared to have been approved by the French people in a national referendum, the fairness and legality of which has been questioned ever since. The coup of 1851 definitely alienated the republicans. Victor Hugo, who had hitherto shown support toward Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, decided to go into exile after the coup, and became one of the harshest critics of Napoléon III.

Emperor of the French

Authoritarian empire

New constitutional statutes were passed which officially maintained an elected Parliament and reestablished universal male suffrage. However, the Parliament now became irrelevant as real power was completely concentrated in the hands of Louis-NapolĂ©on and his bureaucracy. Exactly one year later, on 2 December 1852, after approval by another referendum, the Second Republic was officially ended and the Empire restored, ushering in the Second French Empire. President Louis-NapolĂ©on Bonaparte became Emperor NapolĂ©on III. Although Napoleon II had never really ruled, his choice of the designation âIIIâ served to legitimize his reign, at least in the eyes of Bonaparte loyalists. That same year, he began shipping political prisoners and criminals to penal colonies such as Devil's Island or (in milder cases) New Caledonia.

The emperor, still a bachelor, began quickly to look for a wife to produce a legitimate heir. Most of the royal families of Europe were unwilling to marry into the Bonaparte family, and after rebuffs from Princess Carola of Sweden and from Queen Victoria's German niece Princess Adelheid of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, Napoléon decided to lower his sights somewhat and "marry for love," choosing the young, beautiful Countess of Teba, Eugénie de Montijo, a Spanish noblewoman of partial Scottish ancestry who had been brought up in Paris. On April 28, 1855 Napoléon survived an attempted assassination. In 1856, Eugenie gave birth to a legitimate son and heir, Napoléon EugÚne Louis, the Prince Impérial. On January 14, 1858 Napoléon and his wife escaped another assassination attempt, plotted by Felice Orsini.

Liberal empire

Until about 1861, NapolĂ©on's regime exhibited decidedly authoritarian characteristics, using press censorship to prevent the spread of opposition, manipulating elections, and depriving the Parliament of the right to free debate or any real power. In the decade of the 1860s, however, NapolĂ©on III made more concessions to placate his liberal opponents. This change began by allowing free debates in Parliament and public reports of parliamentary debates, continued with the relaxation of press censorship, and culminated in the appointment of the Liberal Ămile Ollivier, previously a leader of the opposition to NapolĂ©on's regime, as acting Prime Minister in 1870. Historians describe this later period as the âLiberal Empire.â

Economic and social policy

The French economy was rapidly modernized under Napoléon III, who wanted his legacy to be that of a reform-minded social engineer. The industrialization of France during this period, in general, appealed to members of both the business interests and the working classes. Downtown Paris was renovated with the clearing of slums, the widening of streets, and the construction of parks according to Baron Haussmann's plan. Working class neighborhoods were relocated to the outskirts of Paris, where factories utilized their labor. Some of his main backers were Saint-Simonians, and these supporters described Napoleon III as the "socialist emperor." Saint-Simonians at this time founded a new type of banking institution, the Credit Mobilier, which sold stock to the public and then used the money raised to invest in industrial enterprises in France. This sparked a period of rapid economic development.

As it turned out, this time period was favorable for industrial expansion. The gold rush in California, and later Australia, increased the European money supply. The steady rise of prices caused by the increase of the money supply encouraged company promotion and investment of capital. The mileage of railways in France increased from 3000 to 16,000 kilometers during the 1850s, and this growth of railways allowed mines and factories to operate at higher rates of productivity. The 55 smaller rail lines of France were merged into 6 major lines, while new iron steamships replaced wooden sailing ships. Between 1859 and 1869, a French company built the Suez Canal, opening a new chapter in global transportation and trade.

Algeria

Algeria had been under French rule since 1830. Compared to previous administrations, Napoleon was far more sympathetic to the native Algerians who appealed to his romantic sentiments. He halted European migration inland, restricting this to the coastal zone. He also freed the Algerian rebel leader Abd al Qadir, who had been promised freedom on surrender but had been imprisoned by the previous administration, giving him a stipend of 150,000 Francs. He also allowed Muslims to serve in the military and civil service on theoretically equal terms and allowed them to emigrate to France. In addition, he gave the option of citizenship; however for Muslims to take this option they had to accept all of the French civil code, including parts governing inheritance and marriage which might conflict with Muslim polygamous tradition, and they had to reject the competence of religious courts. Some Muslims understood this as requiring them to repudiate aspects of Islam in order to obtain citizenship, which was resented.

One of the most influential decisions Louis Napoleon made in Algeria was to change the system of land tenure. While well intentioned, in effect this move destroyed the traditional system of land management and deprived many Algerians of land. While Napoleon did renounce state claims to tribal lands, he also put into place a legalized process of dismantling tribal land ownership in favor of individual land ownership over the course of three generations, though this process was accelerated by later administrations. This process was corrupted by French officials sympathetic to French in Algeria who took much of the land they surveyed into public domain; in addition many tribal leaders, chosen for loyalty to the French rather than influence in their tribe, immediately sold communal land for cash.

Foreign policy

In a speech in 1852, Napoleon III famously proclaimed that "The Empire means peace" ("L'Empire, c'est la paix," literally 'The Empire, it is peace'), reassuring foreign governments that the new Emperor Napoleon would not be an aggressor, unlike Napoleon I. The European powers had prevented Napoleon II from becoming Emperor or even from ruling his motherâs territory in Italy because they feared he had a warlike personality. However, the promise proved illusory; Napoleon III involved France in a series of conflicts throughout his reign. He was thoroughly determined to follow a strong foreign policy to extend France's power and glory. He was also driven by vague dreams of re-casting the map of Europe, sweeping away small principalities to create unified nation-states (which had been Napoleon Iâs vision, too) even when this seemed to have little relevance to France's interests. In this he remained influenced by his youthful liberal-nationalist politics as a member of the Carbonari in Italy. These two factors led Napoleon to a certain adventurism in foreign policy, although this was sometimes tempered by pragmatism.

The Crimean War

Napoleon's challenge to Russia's claims to influence in the Ottoman Empire led to France's successful participation in the Crimean War (March 1854âMarch 1856). During this war Napoleon established a French alliance with Britain, which continued after the war's close. The defeat of Russia and the alliance with Britain gave France increased authority in Europe. This was the first war between European powers since the close of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna, marking a breakdown of the alliance system that had maintained peace for nearly half a century. The war also effectively ended the Concert of Europe and the Quadruple alliance.

East Asia

Napoleon took the first steps to establishing a French colonial influence in Indochina. He approved the launching of a naval expedition in 1858 to punish the Vietnamese for their mistreatment of French Catholic missionaries and force the court to accept a French presence in the country. An important factor in his decision was the belief that France risked becoming a second-rate power by not expanding its influence in East Asia. Also, the idea that France had a civilizing mission was spreading. This eventually led to a full-out invasion in 1861. By 1862 the war was over and Vietnam conceded three provinces in the south, called by the French Cochin-China, opened three ports to French trade, allowed free passage of French warships to Cambodia (which led to a French protectorate over Cambodia in 1867), allowed freedom of action for French missionaries and gave France a large indemnity for the cost of the war. France did not however intervene in the Christian-supported Vietnamese rebellion in Bac Bo, despite the urging of missionaries, or in the subsequent slaughter of thousands of Christians after the rebellion, suggesting that although persecution of Christians was the prompt for the intervention, military and political reasons ultimately drove colonialism in Vietnam.

In China, France took part in the Second Opium War along with the United Kingdom, and in 1860 French troops entered Beijing. China was forced to concede more trading rights, allow freedom of navigation of the Yangtze river, give full civil rights and freedom of religion to Christians, and give France and Britain a huge indemnity. This combined with the intervention in Vietnam set the stage for further French influence in China leading up to a sphere of influence over parts of Southern China.

In 1866, French Navy troops made an attempt to colonize Korea, during the French Campaign against Korea. In 1867, a French Military Mission to Japan was sent, which played a key role in modernizing the troops of the Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu, and even participated on his side against Imperial troops during the Boshin war.

Italy

As President of the Republic, Louis-Napoleon sent French troops to help restore Pope Pius IX as ruler of the Papal States in 1849 after there had been a revolt there in 1848 (although as a Carbonaro he had been involved in plotting a similar revolt in the Papal States during his youth in Italy). This won him support in France from Catholics (although many remained supporters of the Bourbon monarchy at heart). Yet at the same time he had sent an emissary to negotiate with the revolutionary Italian nationalist Guiseppi Mazzini. Napoleon remained attached to the ideal of Italian nationalism which he had embraced in his youth. He also wished particularly to end Austrian rule in Lombardy and Venice (he always nursed a dislike for Austria as the incarnation of conservative, legitimate monarchy and the great barrier to the reconstruction of Europe on nationalist lines, again traceable back to his Carbonari days). He dreamt of re-unifying Italy, which left-wing opinion in France supported while at the same time supporting the Pope in Rome and thus maintaining conservative and Catholic support in France. These contradictory desires were evident in his policy in Italy.

In April-July 1859 Napoléon made a secret deal at PlombiÚres-les-Bains with Cavour, Prime Minister of Piedmont, for France to assist in expelling Austria from the Italian peninsula and bringing about a united Italy, or at least a united northern Italy, in exchange for Piedmont ceding to France Savoy and the Nice region (which was destined to become the so-called French Riviera). He went to war with Austria in 1859 and won a victory at Solferino, which resulted in the ceding of Lombardy to Piedmont by Austria (and in return received Savoy and Nice from Piedmont as promised in 1860). After this had been done, however, Napoleon decided to end French involvement in the war. This early withdrawal, however, failed to prevent central Italy, including most of the Papal states, being incorporated into the new Italian state. This led Catholics in France to turn against Napoleon. Napoleon tried to redress the damage by maintaining French troops in the city of Rome itself, which prevented the Italian government seizing it from the Pope, a policy which Napoleon's devoutly Catholic wife Eugenie fervently supported. However, Napoleon on the whole failed to win back Catholic support at home (and made moves to appeal instead to the anti-Catholic left in his domestic policy in the 1860s, most notably by appointing the anti-clerical Victor Duruy Minister for Education, who further secularized the schooling system). Nonetheless, French troops remained in Rome to protect the Pope until the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.

United States of America

In the beginning of the 1860s, the objectives of the Emperor in foreign policy had been met: France scored several military victories in Europe and abroad, the defeat at Waterloo had been exorcised, and France was once again a significant continental military power.

During the American Civil War, Napoleon III positioned France to lead the pro-Confederate European powers. For a time, Napoleon III inched steadily toward officially recognizing the Confederacy, especially after the crash of the cotton industry and his exercise in regime-changing in Mexico. Some historians have also suggested that he was driven by a desire to keep the American states divided. Through 1862, Napoleon III entertained Confederate diplomats, raising hopes that he would unilaterally recognize the Confederacy. The Emperor, however, could do little without the support of the United Kingdom, and never officially recognized the Confederacy.

Mexico

Napoleon's adventurism in foreign policy is aptly demonstrated by the French intervention in Mexico (January 1862âMarch 1867). Napoleon, using as a pretext the Mexican Republic's refusal to pay its foreign debts, planned to establish a French sphere of influence in North America by creating a French-backed monarchy in Mexico, a project that was supported by Mexican conservatives who grew weary of the anti-clerical tendencies of the Mexican republic. The United States was unable to prevent this contravention of the Monroe Doctrine because of the American Civil War, and if, as Napoleon hoped, the Confederates were victorious in that conflict, he believed they would accept the new regime in Mexico.

With the support of Mexican conservatives and French troops, in 1863 Napoleon installed Habsburg prince Maximilian to reign in Mexico. However, ruling President Benito Juarez and his Republican forces retreated to the countryside and fought against the French troops and the Mexican monarchists.

The combined Mexican monarchist and French forces won victories up until 1865, but then the tide began to turn against them, in part because the American Civil War had ended. The U.S. government was now able to give practical support to the Republicans, supplying them with arms and establishing a naval blockade to prevent French reinforcements arriving from Europe. Napoleon withdrew French troops from Mexico in 1866, which left Maximilian and the Mexican monarchists doomed to defeat in 1867. Despite Napoleon's pleas that he abdicate and leave Mexico, Maximilian refused to abandon the Mexican conservatives who had supported him, and remained alongside them until the bitter end, when he was captured by the Republicans and then shot on June 19, 1867. The complete failure of the Mexican intervention was a humiliation for Napoleon, and he was widely blamed across Europe for Maximilian's death. However, letters have since shown that Napoleon III and Leopold of Belgium both warned Maximilian to not depend on European support.

Prussia

A far more dangerous threat to NapolĂ©on, however, was looming. France saw its dominance on the continent of Europe eroded by Prussia's crushing victory over Austria in the Austro-Prussian War in JuneâAugust 1866. Due in part to his Carbonari past, NapolĂ©on was unable to ally himself with Austria, despite the obvious threat that a victorious Prussia would pose to France. Yet, having decided not to prevent the Prussian rise to power by allying against her, NapolĂ©on also failed to take the opportunity to demand Prussian consent to French territorial expansion in return for France's neutrality. NapolĂ©on only requested that Prussia agree to French annexation of Belgium and Luxembourg after Prussia had already defeated Austria, by which time France's neutrality was no longer needed by Prussia. This extraordinary foreign policy failure saw France gain nothing while allowing Prussia's strength to increase greatly. In part the reason for the Emperor's blunder must be laid on his deteriorating health during this period - he had begun to suffer from a bladder stone that caused him great pain, even preventing NapolĂ©on from riding a horse.[1]

Napoléon's later attempt in 1867 to re-balance the scales by purchasing Luxembourg from its ruler, William III of the Netherlands, was thwarted by a Prussian threat of war. The Luxembourg Crisis ended with France renouncing any claim to Luxembourg in the Treaty of London (1867).

Demise

Napoléon III paid the price for his failure to help defend Austria from Prussia in 1870 when, goaded by the diplomacy of the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck, he began the Franco-Prussian War. This proved disastrous for France, and was instrumental in giving birth to the German Empire, which would take France's place as the major land power on the continent of Europe until the end of World War I. In battle against Prussia in July 1870 the Emperor was captured at the Battle of Sedan (September 2) and was deposed by the forces of the Third Republic in Paris two days later.

Napoleon spent the last few years of his life in exile in England, with Eugenie and his only son. The family lived at Camden Place Chislehurst (Kent), and he died on January 9, 1873. He was haunted to the end by bitter regrets and by painful memories of the battle at which he lost everything; Napoléon's last words, addressed to Dr. Henri Conneau standing by his deathbed, reportedly were, "Were you at Sedan?" ("Etiez-vous à Sedan?")[2] The emperor died during a multistage process to break up a bladder stone. The actual cause of death was apparently kidney failure and septicemia.

Napoléon was originally buried at St. Mary's, the Catholic church in Chislehurst. However, after his son also died in 1879, fighting in the British Army against the Zulus in South Africa, the bereaved Eugenie decided to build a monastery. The building would house monks driven out of France by the anti-clerical laws of the Third Republic, which would provide a suitable resting place for her husband and son. Thus in 1888 Napoléon III's body (and that of his son) was moved to the Imperial Crypt at Saint Michael's Abbey, Farnborough, Hampshire, England. Eugenie, who died many years later in 1920, is now buried there with them. It was reported in 2007 that the French Government is seeking the return of his remains to be buried in France, but that this is opposed by the monks of the abbey.[3]

Napoléon stayed at No. 6 Clarendon Square, Royal Leamington Spa between 1838-1839. The building is now called Napoleon House and has a 'Blue plaque' put up by the local council.

Romances

Louis Napoleon was a lover of women, and had many mistresses. During his reign, it was the task of Count Felix Bacciochi, his social secretary, to arrange for trysts and to procure women for the emperor's favors. His affairs were not trivial sideshows as they distracted him from governing, affected his relationship with the empress, and diminished him in the views of the other European courts.

- Mathilde Bonaparte, his cousin and fiancée;

- Alexandrine ĂlĂ©onore Vergeot, laundress at the prison at Ham, mother of his sons Alexandre Louis EugĂšne and Louis Ernest Alexandre.

- Elisa Rachel Felix, the "most famous actress in Europe";

- Harriet Howard, (1823-1865) wealthy and a major financial backer;

- Virginia Oldoini, Countess de Castiglioni, (1837-1899) sent by Camillo Cavour to influence his politics;

- Marie-Anne Waleska, a possible mistress, wife of Count Alexandre Joseph Count Colonna-Walewski, his relative and foreign minister;

- Justine Marie Le Boeuf, also known as Marguerite Bellanger, actress and acrobatic dancer;

- Countess Louise de Mercy-Argenteau, (1837-1890), likely a platonic relationship, author of The Last Love of an Emperor, her reminiscences of her association with the emperor.

His wife, Eugenie, was able to resist his advances prior to marriage. She was coached by her mother and her friend, Prosper Mérimée to tell him that her heart would be won through piety. She appears not to have liked sex. It is doubted that she allowed further approaches by her husband once she had given him an heir.

By his late forties, Napoleon started to suffer from numerous medical ailments, including kidney disease, bladder stones, chronic bladder and prostate infections, arthritis, gout, obesity, and the effects of chronic smoking. This adversely affected his sexual exploits.

Legacy

Architectural

An important legacy of NapolĂ©on III's reign was the rebuilding of Paris. Part of the design decisions were taken in order to reduce the ability of future revolutionaries to challenge the government by capitalizing on the small, medieval streets of Paris to form barricades. However, this should not overlook the fact that the main reason for the complete transformation of Paris was NapolĂ©on III's desire to modernize Paris based on what he had seen of the modernizations of London during his exile there in the 1840s. With his characteristic social approach to politics, NapolĂ©on III desired to improve health standards and living conditions in Paris with the following goals: build a modern sewage system to improve health, develop new housing with larger apartments for the masses, create green parks all across the city to try to keep working classes away from the pubs on Sunday, etc. Large sections of the city were thus flattened down and the old winding streets were replaced with large thoroughfares and broad avenues. The rebuilding of Paris was directed by Baron Haussmann (1809â1891; Prefect of the Seine dĂ©partement 1853â1870). It was this rebuilding that turned Paris into the city of broad tree-lined boulevards and parks so beloved of tourists today.

With Prosper Mérimée, Napoleon III continued to seek the preservation for numerous medieval buildings in France, which had been left disregarded since the French revolution (a project Mérimée had begun during the July Monarchy). With Viollet-le-Duc acting as chief architect, many buildings were saved, including some of the most famous in France: Notre Dame Cathedral, Mont Saint Michel, Carcassonne, Pierrefonds, Roquetaillade castle and others.

Developing Franceâs infrastructure

Napoléon III also directed the building of the French railway network, which greatly contributed to the development of the coal mining and steel industry in France, radically changing the nature of the French economy, which entered the modern age of large-scale capitalism. The French economy, the second largest in the world at the time (behind the United Kingdom), experienced a very strong growth during the reign of Napoléon III. Names such as steel tycoon EugÚne Schneider or banking mogul James de Rothschild are symbols of the period. Two of France's largest banks, Société Générale and Crédit Lyonnais, still in existence today, were founded during that period. The French stock market also expanded prodigiously, with many coal mining and steel companies issuing stocks. Although largely forgotten by later Republican generations, which only remembered the non-democratic nature of the regime, the economic successes of the Second Empire are today recognized as impressive by historians. The emperor himself, who had spent several years in exile in Victorian Lancashire, was largely influenced by the ideas of the Industrial Revolution in England, and he took particular care of the economic development of the country. He is recognized as the first ruler of France to have taken great care of the economy; previous rulers considering it secondary.

Political legacy

His military adventurism is sometimes considered a fatal blow to the Concert of Europe, which based itself on stability and balance of powers, whereas Napoleon III attempted to rearrange the world map to France's favor even when it involved radical and potentially revolutionary changes in politics. NapolĂ©on III has often been seen as an authoritarian but ineffectual leader who brought France into dubious, and ultimately disastrous, foreign military adventures. On the other hand, his realignment of Franceâs relationship with the United Kingdom laid the foundation of an alliance that would serve Franceâs interests well during World War I and World War II, arguably ensuring her very survival as a nation state. NapolĂ©on III, to this day, has not enjoyed the prestige that NapolĂ©on I enjoyed. Victor Hugo portrayed him as "NapolĂ©on the small" (NapolĂ©on le Petit), a mere mediocrity in contrast with NapolĂ©on I "The Great," presented as a military and administrative genius.[4] In France, such arch-opposition from the age's central literary figure, whose attacks on NapolĂ©on III were obsessive and powerful, made it impossible for a very long time to assess his reign objectively. Karl Marx mocked NapolĂ©on III by saying that history repeats itself: "The first time as tragedy, the second time as farce."[5]

Historians have also emphasized his attention to the fate of working classes and poor people. His book Extinction du paupérisme ("Extinction of pauperism"), which he wrote while imprisoned at the Fort of Ham in 1844, contributed greatly to his popularity among the working classes and thus his election win in 1848. Throughout his reign the emperor worked to alleviate the sufferings of the poor, on occasion breaching the nineteenth-century economic orthodoxy of complete laissez-faire and using state resources or interfering in the market. Among other things, the Emperor granted the right to strike to French workers in 1864, despite intense opposition from corporate lobbies.

The Emperor also ordered the creation of three large parks in Paris (Parc Monceau, Parc Montsouris, and Parc des Buttes Chaumont) with the clear intention of offering them for poor working families as an alternative to the pub (bistro) on Sundays, much as Victoria Park in London was also built with the same social motives in mind. The pattern of his political career in which initial democratic success was followed by the assumption of dictatorial power while maintaining the fiction of democracy may prove the adage that power corrupts. The careers of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini followed a similar pattern. However, in the context of post-revolutionary France, Napoleon II may perhaps be partly excused for behaving as he did, given that ever since the Revolution France had oscillated between republicanism and various forms of monarchy. There simply was no shared vision of how society should be governed. On the one hand, as the Bonaparte heir, Napoleon III obviously believed that he had a right, by virtue of birth, to rule that required no validation. His early attempts to seize power were based on this claim. Later, he appears to have had a genuine concern to improve the economic conditions of the people, and to develop Franceâs infrastructure. Whatever his moral failing, to have had such descriptions as âsocialistâ and âliberalâ applied to him, suggests that as a ruler he was not completely without merit.

Ancestry

The question of his paternity remains ambiguous, as his parents were estranged and Hortense had her lovers. However, the parents met briefly between June 23 and July 6, 1807, eight months prior to his birth. Speculation on this topic was a favorite of his detractors.[6]

| Napoleon III of France | Father: Louis Bonaparte |

Paternal Grandfather: Carlo Buonaparte |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Giuseppe Maria Buonaparte |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Maria-Saveria Paravicini | |||

| Paternal Grandmother: Letizia Ramolino |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Giovanni Geronimo Ramolino | ||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Angela Maria Pietrasanta | |||

| Mother: Hortense de Beauharnais |

Maternal Grandfather: Alexandre, vicomte de Beauharnais |

Maternal Great-grandfather: François de Beauharnais, Marquess de la La Ferté-Beauharnais | |

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Marie Henriette Pyvart de Chastullé | |||

| Maternal Grandmother: Joséphine de Beauharnais |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Joseph-Gaspard de Tascher, chevalier, seigneur de la Pagerie, lieutenant of infantry of the navy | ||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Rose-Claire des Vergers de Sanois |

| House of Bonaparte Born: 20 April 1808;Â Died: 9 January 1873 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by: Louis-EugĂšne Cavaignac |

President of the French Second Republic December 20, 1848 â December 2 1852 |

became Emperor |

| Head of State of France December 20, 1848 â September 4 1870 |

Succeeded by: Louis Jules Trochu | |

| Regnal Titles

| ||

| Preceded by: Louis-Philippe of France |

Emperor of the French December 2, 1852 â September 4, 1870 |

Empire dissolved |

| Titles in pretence

| ||

| Preceded by: Louis Bonaparte |

* NOT REIGNING * Emperor of the French (July 25, 1846 â December 2, 1852) * Reason for Succession Failure: * Bourbon Restoration (1815â1830) |

became Emperor |

| New Title French Third Republic declared |

* NOT REIGNING * Emperor of the French (September 4, 1870 â January 9, 1873) |

Succeeded by: Napoléon IV |

Notes

- â Review: The Two Marshals. written by historian Philip Guedalla, June 1943, . Bazaine and Retain. TIME. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- â E. Cobham Brewer, 1898. Dying Sayings. Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- â 2007. French seeking emperor's corpse. The Telegraph (UK). Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- â Victor Hugo. 1992. Napoleon the Little. (New York, NY: Howard Fertig. ISBN 978-0865274082)

- â Karl Marx, 1852. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Chapter one, line one. marxists.org. (Chapters 1 & 7 are translated by Saul K. Padover from the German edition of 1869; Chapters 2 through 6 are based on the third edition, prepared by Engels (1885), as translated and published by Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1937; First Published: First issue of Die Revolution, 1852, New York.) Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- â John Bierman. 1988. Napoleon III and his carnival empire. (New York, NY: St. Martin's Press)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baguley, David. 2000. Napoleon III and his regime: an extravaganza. (Modernist studies.) Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807126240.

- Bierman, John. 1988. Napoleon III and his carnival empire. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312018276.

- Bresler, Fenton S. 1999. Napoleon III: a life. New York, NY: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 9780786706600.

- Echard, William E. 1983. Napoleon III and the Concert of Europe. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807110560.

- Hugo, Victor. (1852) 1992. Napoleon the Little. New York, NY: Howard Fertig. ISBN 978-0865274082

- McMillan, James F. 1991. Napoleon III. London, UK: Longman. ISBN 9780582494831.

- Wetzel, David. 2001. A duel of giants: Bismarck, Napoleon III, and the origins of the Franco-Prussian War. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299174903.

- Williams, Roger Lawrence. 1972. The Mortal Napoleon III. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691051925.

This article incorporates text from the EncyclopĂŠdia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved June 2, 2025.

- History of Julius Caesar vol. 1 at MOA. written by Napoleon III, Emperor of the French

- History of Julius Caesar vol. 2 at MOA. written by Napoleon III, Emperor of the French

- Histoire de Jules CĂ©sar (Volume 1) in French at archive.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.