Difference between revisions of "State religion" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (185 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Images OK}} | + | {{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}} |

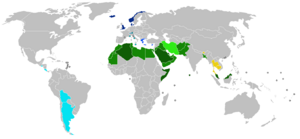

[[Image:State Religions.png|right|thumb|300px|Nations with state religions: | [[Image:State Religions.png|right|thumb|300px|Nations with state religions: | ||

{{legend|#EBCF16|[[Theravada Buddhism]] or Vajrayana Buddhism}} | {{legend|#EBCF16|[[Theravada Buddhism]] or Vajrayana Buddhism}} | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

]] | ]] | ||

| − | A '''state religion''' (also called an '''official religion''', '''established church''' or '''state church''') is a [[religion|religious]] body or [[creed]] officially endorsed by the state. | + | A '''state religion''' (also called an '''official religion''', '''established church''' or '''state church''') is a [[religion|religious]] body or [[creed]] officially endorsed by the [[state]]. In some countries more than one religion or denomination has such standing. There are also a variety of ways such endorsement occurs. The term ''state church'' is associated with [[Christianity]], and is sometimes used to denote a specific national branch of Christianity such as the [[Greek Orthodox Church]] or the [[Church of England]]. State religions exist in some countries because the national identity has historically had a specific religious identity as an inseparable component. It is also possible for a [[national church]] to be established without being under state control as the [[Roman Catholic Church]] is in some countries. In countries where state religions exist, the majority of its residents are usually adherents. A population's allegiance towards the state religion is often strong enough to prevent them from joining another religious group. There is also a tendency for religious freedom to be curtailed to varying degrees where there is an established religion. A state without a state religion is called a secular state. The relationship between [[Church and State|church and state]] is complex and has a long history. |

| + | |||

| + | The degree and nature of state backing for a denomination or creed designated as a state religion can vary. It can range from mere endorsement and financial support, with freedom for other faiths to practice, to prohibiting any competing religious body from operating and to persecuting the followers of other faiths. It all depends upon the political culture and the level of tolerance in that country. Some countries with official religions have laws that guarantee the [[freedom of worship]], full liberty of [[conscience]], and places of worship for all citizens; and implement those laws more than other countries that do not have an official or established state religion. Many sociologists now consider the effect of a state church as analogous to a chartered [[monopoly]] in religion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The lack of a [[separation of church and state|separation]] between religion and state means that religion may play an important role in the public life a country such as [[coronation]]s, [[investiture]]s, legislation, [[marriage]], [[education]] and [[government]]. What might otherwise be purely civil events may be given a religious context with all the spiritual legitimacy that implies. It also means that civil authorities may be involved in the governing of the institution including its [[doctrine]], structure and appointment of its leaders. Religious authority is very significant and civil authorities often want to control it. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | There have also been religious states where the ruler may be believed to be divine and the state has a sacred and absolute authority beyond which there was no appeal. It was to the state that a person belonged, it was state gave a person his or her identity, determined what was right or wrong and was the sole or at least highest legitimate object of a person's loyalty and devotion. The state would have its own rituals, symbols, mythical founder, belief system and personality cult associated with the ruler. Examples of such states were [[ancient Egypt]], the [[pagan]] [[Roman Empire]], [[fascism|Fascist]] [[Germany]] and the [[Soviet Union]]. | ||

==Historical Origins== | ==Historical Origins== | ||

| − | + | ===Antiquity=== | |

| + | State religions were known in ancient times in the empires of [[Egypt]] and [[Sumer]] and ancient Greece when every city state or people had its own god or gods. The religions had little ethical content and the main purpose of worship was to petition the gods to protect the city or the state and make it victorious over its enemies. There was often a powerful personality cult associated with the ruler. Sumerian kings came to be viewed as divine soon after their reigns, like [[Sargon]] the Great of Akkad. One of the first rulers to be proclaimed a god during his actual reign was [[Gudea of Lagash]], followed by some later kings of [[Ur]]. The state religion was integral to the power base of the reigning government, such as in [[ancient Egypt]], where [[Pharaoh]]s were often thought of as embodiments of the god [[Horus]]. | ||

| − | In the [[Persian Empire]], | + | In the [[Persian Empire]], [[Zoroastrianism]] was the state religion of the [[Sassanid dynasty]] which lasted until 651 C.E., when Persia was conquered by the armies of [[Islam]]. However, [[Zoroastrianism]] persisted as the state religion of the independent state of [[Hyrcania]] until the fifteenth century. |

| − | The | + | ===China=== |

| + | In [[China]], the [[Han Dynasty]] (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.) made [[Confucianism]] the ''de facto'' state religion, establishing tests based on Confucian texts as an entrance requirement to government service. The Han emperors appreciated the social order that is central to Confucianism. Confucianism would continue to be the state religion until the [[Sui Dynasty]] (581-618 C.E.), when it was replaced by [[Mahayana Buddhism]]. Neo-Confucianism returned as the ''de facto'' state religion sometime in the tenth century. Note however, there is a debate over whether Confucianism (including Neo-Confucianism) is a religion or merely a system of [[ethics]]. | ||

| − | + | ===The Roman Empire=== | |

| + | The State religion of the [[Roman Empire]] was Roman polytheism, centralized around the emperor. With the title ''Pontifex Maximus,'' the emperor was honored as a 'god' either posthumously or during his reign. Failure to worship the emperor as a god was at times punishable by death, as the Roman government sought to link [[emperor worship]] with loyalty to the Empire. Many Christians were [[persecution|persecuted]], tortured and killed because they refused to worship the emperor. | ||

| − | + | In 313 C.E., [[Constantine I]] and Licinius, the two ''Augusti,'' enacted the [[Edict of Milan]] allowing religious freedom to everyone within the Roman Empire. The Edict of Milan stated that Christians could openly practice their religion unmolested and unrestricted and ensured that properties taken from Christians be returned to them unconditionally. Although the Edict of Milan allowed religious freedom throughout the empire, and did not abolish nor disestablish the Roman state cult, in practice it permitted official favor for Christianity, which Constantine intended to make the new state religion. | |

| + | [[Image:Byzantinischer Mosaizist um 1000 002.jpg|thumb|225px|''Constantine the Great,'' mosaic in [[Hagia Sophia]], [[Constantinople]], c. 1000]] | ||

| − | + | Seeking unity for his new state religion, Constantine summoned the [[First Council of Nicaea]] in 325 C.E. Disagreements between different Christian sects was causing social disturbances in the empire, and he wanted Christian leaders to come to some agreement about what they believed and if necessary to enforce that belief or expel those who disagreed. This set a significant precedent for subsequent state involvement and interference in the internal workings of the Christian Church. | |

| − | + | The Christian lifestyle was generally admired and Christians managed government offices with exceptional honesty and integrity. [[Catholic|Roman Catholic]] Christianity, as opposed to Arianism and [[Gnosticism]], was declared to be the state religion of the [[Roman Empire]] on February 27, 380 C.E. by the decree ''De Fide Catolica'' of Emperor [[Theodosius I]].<ref>"Theodosian Code XVI.i.2" (excerpt from Henry Bettenson, ed., ''Documents of the Christian Church.'' (London: Oxford University Press, 1943) at Paul Halsall.[http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/theodcodeXVI.html] ''Medieval Sourcebook'': Banning of Other Religions. (June 1997) ''Fordham University'' Retrieved August 9, 2008</ref> This declaration was based on the expectation that as an official state religion it would bring unity and stability to the empire. Theodosius then proceeded to destroy pagan temples and built churches in their place. | |

| − | + | ===Eastern Orthodoxy=== | |

| + | The first country to make Christianity the national religion was [[Armenia]]. It deliberately adopted a version of Christianity which was unorthodox so as to establish and maintain their national distinctiveness and independence. This pattern of a [[national church]] was common in most orthodox countries with many of them becoming the de facto state religion. | ||

| − | + | Following on from the precedent established by Constantine I, it sometimes appeared in Eastern Christianity that the head of the state was also the head of the church and supreme judge in religious matters. This is called [[caesaropapism]] and was most frequently associated with the [[Byzantium|Byzantine Empire]]. In reality the relationship was more like an interdependence, or symphony, between the imperial and ecclesiastical institutions. Ideally it was a dynamic and moral relationship. In theory the emperor was neither doctrinally infallible nor invested with priestly authority and many times the emperor failed to get his way. | |

| − | + | However, it was normal for the Emperor to act as the protector of the church and be involved in its administrative affairs. Constantine was called “the overseer of external” (as opposed to spiritual) church problems by [[Eusebius of Caesarea]]. Emperors chaired church councils, and their will was decisive in appointing of patriarchs and deciding the territory they would have authority over. | |

| − | + | In [[Russia]] [[caesaropapism]] was more a reality. [[Ivan IV of Russia|Ivan the Dread]] would brook no opposition or criticism from the church and later [[Peter the Great]] abolished the [[patriarchate]] and in 1721 made the church a department of the state. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | ===The Protestant Reformation=== |

| + | The [[Protestant Reformation]] criticized the dogmas and corruption of the [[papacy]]. In [[Germany]] [[Martin Luther]] required the protection of his political ruler [[Frederick the Wise]]. He and other German princes supported Luther and adopted his reforms as it was a way that they could free themselves from the control of the papacy. In exchange for protection, Luther and the German Reformation thus ceded more temporal authority to the State leading to the possibility of less of a moral check on political power. This arrangement is known as [[Erastianism]]. Some historians thus blame Luther for the possibility of the eventual rise of [[Adolf Hitler]]. | ||

| − | In | + | In [[England]] [[Henry VIII]] nationalized the Catholic Church in England creating a state church, the [[Church of England]] to suit his dynastic needs. The 1534 [[Act of Supremacy]] made Henry 'the only head in earth of the Church of England.' During the reign of his son [[Edward VI of England|Edward VI]] a more thoroughgoing Protestantization was imposed by royal rule including the first ''English Prayer Book.'' Under [[Elizabeth I]] the Church was effectively subordinate to the interests of the state. The monarch's title was also modified to 'supreme governor'. The 1593 Act of Uniformity made it a legal requirement for everyone to attend the established church on pain of banishment. Those attending an alternative service were regarded as disloyal and could be imprisoned or banished. |

| − | In | + | In reaction to this a [[Puritan]] movement developed within the church which wanted to return to the ecclesial life of the early church. This wing became more [[Separatist]] and later led to the emergence of the Independent and [[Congregationalist]] movements. This culminated in the [[English Revolution]] which shattered the relationship between church and state. Pluralism accompanied the Protectorate of [[Oliver Cromwell]]. The state though still controlled the church and replaced episcopal government with the presbyterian system. The [[Restoration]] saw the attempt to re-establish a single church to provide cement and stability for a deeply disunited and unsettled society. Several laws were passed to enforce attendance at the established church. From the eighteenth century these was gradually relaxed and repealed as it became clear that non-conformists were loyal. |

| − | + | Puritans and other non-conformists who emigrated to America decided that there should be a [[Separation of Church and State in the United States|separation between church and state]]. | |

| − | + | ==The Present Situation in Europe== | |

| + | Despite a general consensus among political philosophers in favor of the religious neutrality of the liberal democratic state, nowhere in Europe is this principle fully realized. From Ireland to Russia, Norway to Malta, a bewildering array of patterns of church-state relations reflect different confessional traditions, contrasting histories and distinctive constitutional and administrative practices.<ref>John Madeley & Zsolt Enyedi, (eds.) ''Church and State in Contemporary Europe: the chimera of neutrality.'' (London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003)</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Great Britain=== | |

| + | In [[Great Britain]], there was a campaign by Liberals, dissenters and nonconformists to disestablish the [[Church of England]] in the late nineteenth century. This was mainly because of the privileged position of Anglicans. For example until 1854 and 1856 respectively, only practicing Anglicans could matriculate at Oxford and Cambridge Universities. The disestablishment movement was unsuccessful in part because the repeal of civil disabilities reduced the basis for the sense of injustice. There is now complete freedom of religion in the UK. The conflict between Anglicans and the [[Free Church]] focused on the emerging national educational system. The Free Churches didn't want the state funded schools to be controlled by the Anglican Church. However there still remained the theological and ecclesiological objection to the state's control of the inner life of the church. | ||

| − | + | The [[Church of Ireland]] was disestablished in 1869 (effective 1871). The Anglican Church was disestablished in [[Wales]] in 1920, the Church in Wales becoming separated from the Church of England in the process. The main objection to disestablishment was articulated by the [[Archbishop of Canterbury]] [[Cosmo Lang]]: <blockquote>The question before us is whether in that inward region of the national life where anything that can be called its unity and character is expressed, there is not to be this witness to some ultimate sanction to which the nation looks, some ultimate ideal it proposes. It is in our judgement a very serious thing for a state to take out of that corporate heart of its life any acknowledgment at all of its concern with religion.</blockquote> | |

| + | [[Image:Queencrown.jpg|right|thumb|The [[coronation]] of Queen Elizabeth II, June 2, 1953. Prince Philip swears his allegiance to his wife and newly crowned sovereign.]] | ||

| + | The state has continued to be involved in the affairs of the Church of England. in the 1928-1929 Prayer Book controversy [[Parliament]] rejected the proposals of the Church Assembly. Since then there have been several steps to make the Church more independent and self-governing. In 2008 the Prime Minister Gordon Brown agreed to always accept the suggestion of the Church on the appointment of Bishops. Currently there is no serious impetus towards disestablishment. The Church of England continues to be intimately involved with the state from the parish government to education, having Bishops sitting in the legislature and the coronation of a monarch. About 36% of primary state schools and 17% of secondary state schools are church schools. The Church of Scotland considers itself to be a "national church" rather than an established church, as it is entirely independent of Parliamentary control in spiritual matters although it maintains links with the monarchy. | ||

| − | + | The Jewish [[Beth Din]] is recognized under law and its rulings are binding if both sides in a dispute accept its jurisdiction. Under arbitration law Muslim [[Sharia]] courts are also recognized and their rulings can be enforced if both sides seek a ruling. Both the Bet Din and Sharia courts can only make rulings that fall within English Law and citizens always have the right to seek redress in the civil courts. Some elements of Sharia financial law have been incorporated into English Law so that Muslims who cannot pay or receive interest do not have to pay tax twice on property deals. | |

| − | == | + | ===Germany=== |

| − | + | In [[Germany]] there are two official state churches, [[Catholic]] and [[Lutheran Church|Lutheran]]. Reforms under Frederick in Prussia can be compared to Napoleon's [[Concordat of 1801]] in France. The state collects the church tithe through the taxation system and determines the salaries of the clergy of the two official denominations and they also have a right to approve a candidate's educational background and political opinions. Clergy in Germany's established religions are among the most vociferous opponents of new religious movements in Europe, like [[Scientology]], because the spread of such religions undermines tax revenue gained from nominal members in one of the official religions that is used to support them. Catholic priests and Lutheran ministers conduct religious education in state schools for their respective pupils. | |

| − | === | + | Religious bodies have to register with the state to be legitimate. |

| − | The following states | + | |

| + | ===Russia=== | ||

| + | In [[Russia]] all religions were severely persecuted under [[communism]] for seventy years. Tens of thousands of priests were killed and millions of ordinary believers suffered for the faith. After the collapse of communism a 1993 law on religion proclaimed a secular state, guaranteed religious freedom, the separation of religion and state while recognizing the special contribution of [[Russian Orthodox Church|Orthodoxy]] to Russia and respecting the traditional religions of [[Christianity]], [[Islam]], [[Buddhism]] and [[Judaism]]. In 1997 a law was passed that gave a privileged position to the Russian Orthodox Church, maintained the position of the other four religions but restricted the rights of other religions and sects. The Orthodox Church is also becoming more active in the educational system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Current Global overview== | ||

| + | ===Christianity=== | ||

| + | The following states give some official recognition to some form of [[Christianity]] although the actual legal status varies considerably: | ||

====Roman Catholic==== | ====Roman Catholic==== | ||

| − | + | [[Argentina]], [[Bolivia]], [[Costa Rica]], [[El Salvador]], [[Germany]], [[Liechtenstein]], [[Malta]], [[Monaco]], [[Slovakia]], some cantons of [[Switzerland]], and [[Vatican City]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Eastern Orthodox==== | ====Eastern Orthodox==== | ||

| − | + | [[Cyprus]], [[Moldova]], [[Greece]], [[Finland]] and [[Russia]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Lutheran==== | ====Lutheran==== | ||

| − | + | [[Germany]], [[Denmark]], [[Iceland]], [[Norway]] and [[Finland]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Anglican==== | ====Anglican==== | ||

| − | + | [[England]]. | |

| − | |||

====Reformed==== | ====Reformed==== | ||

| − | + | [[Scotland]] and some cantons of [[Switzerland]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Old Catholic==== | ====Old Catholic==== | ||

| − | + | Some cantons of Switzerland. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Islam=== |

| − | Countries | + | Countries where [[Islam]] is the official religion: [[Afghanistan]], [[Algeria]] (Sunni), [[Bahrain]], [[Bangladesh]], [[Brunei]], [[Comoros]] (Sunni), [[Egypt]], [[Iran]] (Shi'a), [[Iraq]], [[Jordan]](Sunni), [[Kuwait]], [[Libya]], [[Malaysia]] (Sunni), [[Maldives]], [[Mauritania]] (Sunni), [[Morocco]], [[Oman]], [[Pakistan]] (Sunni), [[Qatar]], [[Saudi Arabia]], [[Somalia]] (Sunni), [[Tunisia]], [[United Arab Emirates]], [[Yemen]], and [[Russia]] where it one of four recognized religions. |

| − | + | ===Judaism=== | |

| − | + | [[Israel]] and [[Russia]] where it is one of four recognized religions. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Buddhism=== |

| − | + | [[Bhutan]], [[Cambodia]], [[Russia]] ([[Kalmykia]] is a Buddhist republic within the [[Russian Federation]]), [[Sri Lanka]], [[Thailand]], Tibet Government in Exile (Gelugpa school of [[Tibetan Buddhism]]). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Hinduism=== |

| − | + | [[Nepal]] was once the world's only [[Hindu]] state, but has ceased to be so following a declaration by the Parliament in 2006. | |

| − | === | + | ===States without an official religion=== |

| − | + | These states do not profess any state religion, and are generally secular or laist. Countries which do not have an officially recognized religion include: [[Australia]], [[Azerbaijan]], [[Canada]], [[Chile]], [[Cuba]], [[People's Republic of China|China]], [[France]], [[India]], [[Republic of Ireland|Ireland]], [[Jamaica]], [[Japan]]<ref>From the Meiji era to the first part of the Showa era in [[Japan]], ''Koshitsu Shinto'' was established as the national religion. According to this, the [[emperor of Japan]] was an arahitogami, an incarnate divinity and the offspring of goddess [[Amaterasu]]. As the emperor was, according to the constitution, "head of the empire" and "supreme commander of the Army and the Navy," every Japanese citizen had to obey his will and show absolute loyalty until the end of World War II.</ref>, [[Kosovo]]<ref>[http://www.kushtetutakosoves.info/?cid=2,247 Draft Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo] Retrieved August 9, 2008.</ref>, [[Lebanon]]<ref>(although president must always remain a [[Maronite]] Catholic, and prime minister a Sunni Muslim)</ref>, [[Mexico]], [[Montenegro]], [[Nepal]]<ref>(declared a secular state on May 18, 2006, by the newly resumed House of Representatives)</ref>, [[New Zealand]], [[Nigeria]], [[North Korea]], [[Romania]], [[Singapore]], [[South Africa]], [[South Korea]], [[Spain]], [[Turkey]], [[United States]], [[Venezuela]], [[Vietnam]]. | |

| − | + | ===Established churches and former state churches=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==Established churches and former state churches== | ||

{| class="sortable wikitable" | {| class="sortable wikitable" | ||

| Line 260: | Line 151: | ||

| [[Finland]]<ref>Finland's State Church was the Church of Sweden until 1809. As an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia 1809-1917, Finland retained the Lutheran State Church system, and a state church separate from Sweden, later named the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, was established. It was detached from the state as a separate judicial entity when the new church law came to force in 1870. After Finland had gained independence in 1917, religious freedom was declared in the constitution of 1919 and a separate law on religious freedom in 1922. Through this arrangement, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland lost its position as a state church but gained a constitutional status as a national church alongside with the Finnish Orthodox Church, whose position however is not codified in the constitution.</ref> || Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland || Lutheran || 1870/1919 | | [[Finland]]<ref>Finland's State Church was the Church of Sweden until 1809. As an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia 1809-1917, Finland retained the Lutheran State Church system, and a state church separate from Sweden, later named the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, was established. It was detached from the state as a separate judicial entity when the new church law came to force in 1870. After Finland had gained independence in 1917, religious freedom was declared in the constitution of 1919 and a separate law on religious freedom in 1922. Through this arrangement, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland lost its position as a state church but gained a constitutional status as a national church alongside with the Finnish Orthodox Church, whose position however is not codified in the constitution.</ref> || Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland || Lutheran || 1870/1919 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[France]]<ref>In France the Concordat of 1801 made the Roman Catholic, Calvinist and Lutheran churches state-sponsored religions, as well as [[Judaism]].</ref> || [[Roman Catholic Church]] || [[Catholic]] || 1905 | + | | [[France]]<ref>In France, the Concordat of 1801 made the Roman Catholic, Calvinist and Lutheran churches state-sponsored religions, as well as [[Judaism]].</ref> || [[Roman Catholic Church]] || [[Catholic]] || 1905 |

|- | |- | ||

| [[Georgia]] || Georgian Orthodox Church || Eastern Orthodox || 1921 | | [[Georgia]] || Georgian Orthodox Church || Eastern Orthodox || 1921 | ||

| Line 272: | Line 163: | ||

| Hesse || Evangelical Church of Hesse and Nassau || Lutheran || 1918 | | Hesse || Evangelical Church of Hesse and Nassau || Lutheran || 1918 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[Hungary]]<ref>In Hungary the constitutional laws of 1848 declared five established churches on equal status: the [[Roman Catholic]], Calvinist, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox and Unitarian Church. In 1868 the law was ratified again after the Ausgleich. In 1895 [[Judaism]] was also recognized as the sixth established church. In 1948 every distinction between the different denominations were abolished.</ref> || [[Roman Catholic Church]] || [[Catholic]] || 1848 | + | | [[Hungary]]<ref>In Hungary, the constitutional laws of 1848 declared five established churches on equal status: the [[Roman Catholic]], Calvinist, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox and Unitarian Church. In 1868 the law was ratified again after the Ausgleich. In 1895 [[Judaism]] was also recognized as the sixth established church. In 1948 every distinction between the different denominations were abolished.</ref> || [[Roman Catholic Church]] || [[Catholic]] || 1848 |

|- | |- | ||

| [[Iceland]] || Lutheran Evangelical Church || Lutheran || no | | [[Iceland]] || Lutheran Evangelical Church || Lutheran || no | ||

| Line 350: | Line 241: | ||

| Württemberg || Evangelical Church of Württemberg || Lutheran || 1918 | | Württemberg || Evangelical Church of Württemberg || Lutheran || 1918 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Berg, Thomas C. | + | *Berg, Thomas C. 2004. ''The State and Religion in a Nutshell.'' West Group Publishing. ISBN 978-0314148858 |

| − | *Brown, L. Carl. | + | *Brown, L. Carl. 2001. ''Religion and State.'' Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231120395 |

| − | *Fox, Jonathan. | + | *Fox, Jonathan. 2008. ''A World Survey of Religion and the State.'' Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521707589 |

| + | *Hasson, Kevin Seamus. 2005. ''The Right to Be Wrong: Ending the Culture War Over Religion in America.'' Encounter Books. ISBN 1594030839 | ||

| + | *Madeley, John & Zsolt Enyedi, eds. 2003. ''Church and State in Contemporary Europe: the chimera of neutrality.'' London: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 0714683299 | ||

| + | *Weller, Paul. 2005. ''Time For A Change: Reconfiguring Religion, State And Society.'' London: T. & T. Clark. ISBN 978-0567084873 | ||

| + | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:54, 9 February 2023

A state religion (also called an official religion, established church or state church) is a religious body or creed officially endorsed by the state. In some countries more than one religion or denomination has such standing. There are also a variety of ways such endorsement occurs. The term state church is associated with Christianity, and is sometimes used to denote a specific national branch of Christianity such as the Greek Orthodox Church or the Church of England. State religions exist in some countries because the national identity has historically had a specific religious identity as an inseparable component. It is also possible for a national church to be established without being under state control as the Roman Catholic Church is in some countries. In countries where state religions exist, the majority of its residents are usually adherents. A population's allegiance towards the state religion is often strong enough to prevent them from joining another religious group. There is also a tendency for religious freedom to be curtailed to varying degrees where there is an established religion. A state without a state religion is called a secular state. The relationship between church and state is complex and has a long history.

The degree and nature of state backing for a denomination or creed designated as a state religion can vary. It can range from mere endorsement and financial support, with freedom for other faiths to practice, to prohibiting any competing religious body from operating and to persecuting the followers of other faiths. It all depends upon the political culture and the level of tolerance in that country. Some countries with official religions have laws that guarantee the freedom of worship, full liberty of conscience, and places of worship for all citizens; and implement those laws more than other countries that do not have an official or established state religion. Many sociologists now consider the effect of a state church as analogous to a chartered monopoly in religion.

The lack of a separation between religion and state means that religion may play an important role in the public life a country such as coronations, investitures, legislation, marriage, education and government. What might otherwise be purely civil events may be given a religious context with all the spiritual legitimacy that implies. It also means that civil authorities may be involved in the governing of the institution including its doctrine, structure and appointment of its leaders. Religious authority is very significant and civil authorities often want to control it.

There have also been religious states where the ruler may be believed to be divine and the state has a sacred and absolute authority beyond which there was no appeal. It was to the state that a person belonged, it was state gave a person his or her identity, determined what was right or wrong and was the sole or at least highest legitimate object of a person's loyalty and devotion. The state would have its own rituals, symbols, mythical founder, belief system and personality cult associated with the ruler. Examples of such states were ancient Egypt, the pagan Roman Empire, Fascist Germany and the Soviet Union.

Historical Origins

Antiquity

State religions were known in ancient times in the empires of Egypt and Sumer and ancient Greece when every city state or people had its own god or gods. The religions had little ethical content and the main purpose of worship was to petition the gods to protect the city or the state and make it victorious over its enemies. There was often a powerful personality cult associated with the ruler. Sumerian kings came to be viewed as divine soon after their reigns, like Sargon the Great of Akkad. One of the first rulers to be proclaimed a god during his actual reign was Gudea of Lagash, followed by some later kings of Ur. The state religion was integral to the power base of the reigning government, such as in ancient Egypt, where Pharaohs were often thought of as embodiments of the god Horus.

In the Persian Empire, Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Sassanid dynasty which lasted until 651 C.E., when Persia was conquered by the armies of Islam. However, Zoroastrianism persisted as the state religion of the independent state of Hyrcania until the fifteenth century.

China

In China, the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.) made Confucianism the de facto state religion, establishing tests based on Confucian texts as an entrance requirement to government service. The Han emperors appreciated the social order that is central to Confucianism. Confucianism would continue to be the state religion until the Sui Dynasty (581-618 C.E.), when it was replaced by Mahayana Buddhism. Neo-Confucianism returned as the de facto state religion sometime in the tenth century. Note however, there is a debate over whether Confucianism (including Neo-Confucianism) is a religion or merely a system of ethics.

The Roman Empire

The State religion of the Roman Empire was Roman polytheism, centralized around the emperor. With the title Pontifex Maximus, the emperor was honored as a 'god' either posthumously or during his reign. Failure to worship the emperor as a god was at times punishable by death, as the Roman government sought to link emperor worship with loyalty to the Empire. Many Christians were persecuted, tortured and killed because they refused to worship the emperor.

In 313 C.E., Constantine I and Licinius, the two Augusti, enacted the Edict of Milan allowing religious freedom to everyone within the Roman Empire. The Edict of Milan stated that Christians could openly practice their religion unmolested and unrestricted and ensured that properties taken from Christians be returned to them unconditionally. Although the Edict of Milan allowed religious freedom throughout the empire, and did not abolish nor disestablish the Roman state cult, in practice it permitted official favor for Christianity, which Constantine intended to make the new state religion.

Seeking unity for his new state religion, Constantine summoned the First Council of Nicaea in 325 C.E. Disagreements between different Christian sects was causing social disturbances in the empire, and he wanted Christian leaders to come to some agreement about what they believed and if necessary to enforce that belief or expel those who disagreed. This set a significant precedent for subsequent state involvement and interference in the internal workings of the Christian Church.

The Christian lifestyle was generally admired and Christians managed government offices with exceptional honesty and integrity. Roman Catholic Christianity, as opposed to Arianism and Gnosticism, was declared to be the state religion of the Roman Empire on February 27, 380 C.E. by the decree De Fide Catolica of Emperor Theodosius I.[1] This declaration was based on the expectation that as an official state religion it would bring unity and stability to the empire. Theodosius then proceeded to destroy pagan temples and built churches in their place.

Eastern Orthodoxy

The first country to make Christianity the national religion was Armenia. It deliberately adopted a version of Christianity which was unorthodox so as to establish and maintain their national distinctiveness and independence. This pattern of a national church was common in most orthodox countries with many of them becoming the de facto state religion.

Following on from the precedent established by Constantine I, it sometimes appeared in Eastern Christianity that the head of the state was also the head of the church and supreme judge in religious matters. This is called caesaropapism and was most frequently associated with the Byzantine Empire. In reality the relationship was more like an interdependence, or symphony, between the imperial and ecclesiastical institutions. Ideally it was a dynamic and moral relationship. In theory the emperor was neither doctrinally infallible nor invested with priestly authority and many times the emperor failed to get his way.

However, it was normal for the Emperor to act as the protector of the church and be involved in its administrative affairs. Constantine was called “the overseer of external” (as opposed to spiritual) church problems by Eusebius of Caesarea. Emperors chaired church councils, and their will was decisive in appointing of patriarchs and deciding the territory they would have authority over.

In Russia caesaropapism was more a reality. Ivan the Dread would brook no opposition or criticism from the church and later Peter the Great abolished the patriarchate and in 1721 made the church a department of the state.

The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation criticized the dogmas and corruption of the papacy. In Germany Martin Luther required the protection of his political ruler Frederick the Wise. He and other German princes supported Luther and adopted his reforms as it was a way that they could free themselves from the control of the papacy. In exchange for protection, Luther and the German Reformation thus ceded more temporal authority to the State leading to the possibility of less of a moral check on political power. This arrangement is known as Erastianism. Some historians thus blame Luther for the possibility of the eventual rise of Adolf Hitler.

In England Henry VIII nationalized the Catholic Church in England creating a state church, the Church of England to suit his dynastic needs. The 1534 Act of Supremacy made Henry 'the only head in earth of the Church of England.' During the reign of his son Edward VI a more thoroughgoing Protestantization was imposed by royal rule including the first English Prayer Book. Under Elizabeth I the Church was effectively subordinate to the interests of the state. The monarch's title was also modified to 'supreme governor'. The 1593 Act of Uniformity made it a legal requirement for everyone to attend the established church on pain of banishment. Those attending an alternative service were regarded as disloyal and could be imprisoned or banished.

In reaction to this a Puritan movement developed within the church which wanted to return to the ecclesial life of the early church. This wing became more Separatist and later led to the emergence of the Independent and Congregationalist movements. This culminated in the English Revolution which shattered the relationship between church and state. Pluralism accompanied the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. The state though still controlled the church and replaced episcopal government with the presbyterian system. The Restoration saw the attempt to re-establish a single church to provide cement and stability for a deeply disunited and unsettled society. Several laws were passed to enforce attendance at the established church. From the eighteenth century these was gradually relaxed and repealed as it became clear that non-conformists were loyal.

Puritans and other non-conformists who emigrated to America decided that there should be a separation between church and state.

The Present Situation in Europe

Despite a general consensus among political philosophers in favor of the religious neutrality of the liberal democratic state, nowhere in Europe is this principle fully realized. From Ireland to Russia, Norway to Malta, a bewildering array of patterns of church-state relations reflect different confessional traditions, contrasting histories and distinctive constitutional and administrative practices.[2]

Great Britain

In Great Britain, there was a campaign by Liberals, dissenters and nonconformists to disestablish the Church of England in the late nineteenth century. This was mainly because of the privileged position of Anglicans. For example until 1854 and 1856 respectively, only practicing Anglicans could matriculate at Oxford and Cambridge Universities. The disestablishment movement was unsuccessful in part because the repeal of civil disabilities reduced the basis for the sense of injustice. There is now complete freedom of religion in the UK. The conflict between Anglicans and the Free Church focused on the emerging national educational system. The Free Churches didn't want the state funded schools to be controlled by the Anglican Church. However there still remained the theological and ecclesiological objection to the state's control of the inner life of the church.

The Church of Ireland was disestablished in 1869 (effective 1871). The Anglican Church was disestablished in Wales in 1920, the Church in Wales becoming separated from the Church of England in the process. The main objection to disestablishment was articulated by the Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Lang:

The question before us is whether in that inward region of the national life where anything that can be called its unity and character is expressed, there is not to be this witness to some ultimate sanction to which the nation looks, some ultimate ideal it proposes. It is in our judgement a very serious thing for a state to take out of that corporate heart of its life any acknowledgment at all of its concern with religion.

The state has continued to be involved in the affairs of the Church of England. in the 1928-1929 Prayer Book controversy Parliament rejected the proposals of the Church Assembly. Since then there have been several steps to make the Church more independent and self-governing. In 2008 the Prime Minister Gordon Brown agreed to always accept the suggestion of the Church on the appointment of Bishops. Currently there is no serious impetus towards disestablishment. The Church of England continues to be intimately involved with the state from the parish government to education, having Bishops sitting in the legislature and the coronation of a monarch. About 36% of primary state schools and 17% of secondary state schools are church schools. The Church of Scotland considers itself to be a "national church" rather than an established church, as it is entirely independent of Parliamentary control in spiritual matters although it maintains links with the monarchy.

The Jewish Beth Din is recognized under law and its rulings are binding if both sides in a dispute accept its jurisdiction. Under arbitration law Muslim Sharia courts are also recognized and their rulings can be enforced if both sides seek a ruling. Both the Bet Din and Sharia courts can only make rulings that fall within English Law and citizens always have the right to seek redress in the civil courts. Some elements of Sharia financial law have been incorporated into English Law so that Muslims who cannot pay or receive interest do not have to pay tax twice on property deals.

Germany

In Germany there are two official state churches, Catholic and Lutheran. Reforms under Frederick in Prussia can be compared to Napoleon's Concordat of 1801 in France. The state collects the church tithe through the taxation system and determines the salaries of the clergy of the two official denominations and they also have a right to approve a candidate's educational background and political opinions. Clergy in Germany's established religions are among the most vociferous opponents of new religious movements in Europe, like Scientology, because the spread of such religions undermines tax revenue gained from nominal members in one of the official religions that is used to support them. Catholic priests and Lutheran ministers conduct religious education in state schools for their respective pupils.

Religious bodies have to register with the state to be legitimate.

Russia

In Russia all religions were severely persecuted under communism for seventy years. Tens of thousands of priests were killed and millions of ordinary believers suffered for the faith. After the collapse of communism a 1993 law on religion proclaimed a secular state, guaranteed religious freedom, the separation of religion and state while recognizing the special contribution of Orthodoxy to Russia and respecting the traditional religions of Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Judaism. In 1997 a law was passed that gave a privileged position to the Russian Orthodox Church, maintained the position of the other four religions but restricted the rights of other religions and sects. The Orthodox Church is also becoming more active in the educational system.

Current Global overview

Christianity

The following states give some official recognition to some form of Christianity although the actual legal status varies considerably:

Roman Catholic

Argentina, Bolivia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Germany, Liechtenstein, Malta, Monaco, Slovakia, some cantons of Switzerland, and Vatican City.

Eastern Orthodox

Cyprus, Moldova, Greece, Finland and Russia.

Lutheran

Germany, Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Finland.

Anglican

Reformed

Scotland and some cantons of Switzerland.

Old Catholic

Some cantons of Switzerland.

Islam

Countries where Islam is the official religion: Afghanistan, Algeria (Sunni), Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Comoros (Sunni), Egypt, Iran (Shi'a), Iraq, Jordan(Sunni), Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia (Sunni), Maldives, Mauritania (Sunni), Morocco, Oman, Pakistan (Sunni), Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia (Sunni), Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen, and Russia where it one of four recognized religions.

Judaism

Israel and Russia where it is one of four recognized religions.

Buddhism

Bhutan, Cambodia, Russia (Kalmykia is a Buddhist republic within the Russian Federation), Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tibet Government in Exile (Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism).

Hinduism

Nepal was once the world's only Hindu state, but has ceased to be so following a declaration by the Parliament in 2006.

States without an official religion

These states do not profess any state religion, and are generally secular or laist. Countries which do not have an officially recognized religion include: Australia, Azerbaijan, Canada, Chile, Cuba, China, France, India, Ireland, Jamaica, Japan[3], Kosovo[4], Lebanon[5], Mexico, Montenegro, Nepal[6], New Zealand, Nigeria, North Korea, Romania, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Turkey, United States, Venezuela, Vietnam.

Established churches and former state churches

| Country | Church | Denomination | Disestablished |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | none since independence | n/a | n/a |

| Anhalt | Evangelical Church of Anhalt | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Armenia | Armenian Apostolic Church | Oriental Orthodox | 1921 |

| Austria | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1918 |

| Baden | Roman Catholic Church and the Evangelical Church of Baden | Catholic and Lutheran | 1918 |

| Bavaria | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1918 |

| Brazil | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1890 |

| Brunswick-Lüneburg | Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Brunswick | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Bulgaria | Bulgarian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1946 |

| Chile | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1925 |

| Cuba | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1902 |

| Cyprus | Cypriot Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1977 |

| Czechoslovakia | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1920 |

| Denmark | Church of Denmark | Lutheran | no |

| England | Church of England | Anglican | no |

| Estonia | Church of Estonia | Eastern Orthodox | 1940 |

| Finland[7] | Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland | Lutheran | 1870/1919 |

| France[8] | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1905 |

| Georgia | Georgian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1921 |

| Greece | Greek Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | no |

| Guatemala | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1871 |

| Haiti | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1987 |

| Hesse | Evangelical Church of Hesse and Nassau | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Hungary[9] | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1848 |

| Iceland | Lutheran Evangelical Church | Lutheran | no |

| Ireland | Church of Ireland | Anglican | 1871 |

| Italy | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1984 |

| Lebanon | Maronite Catholic Church/Islam | Catholic/Islam | no |

| Liechtenstein | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | no |

| Lippe | Church of Lippe | Reformed | 1918 |

| Lithuania | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1940 |

| Lübeck | North Elbian Evangelical Church | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Luxembourg | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | ? |

| Republic of Macedonia | Macedonian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | no |

| Malta | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | no |

| Mecklenburg | Evangelical Church of Mecklenburg | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Mexico | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1874 |

| Monaco | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | no |

| Mongolia | Buddhism | n/a | 1926 |

| Netherlands | Dutch Reformed Church | Reformed | 1795 |

| Norway | Church of Norway | Lutheran | no |

| Oldenburg | Evangelical Lutheran Church of Oldenburg | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Panama | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1904 |

| Philippines[10] | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1902 |

| Poland | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1939 |

| Portugal | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1910 |

| Prussia | 13 provincial churches | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Romania | Romanian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1947 |

| Russia | Russian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1917 |

| Thuringia | Evangelical Church in Thuringia | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Saxony | Evangelical Church of Saxony | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Schaumburg-Lippe | Evangelical Church of Schaumburg-Lippe | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Scotland[11] | Church of Scotland | Presbyterian | no |

| Serbia | Serbian Orthodox Church | Eastern | ? |

| Spain | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1978 |

| Sweden | Church of Sweden | Lutheran | 2000 |

| Switzerland | none since the adoption of the Federal Constitution (1848) | n/a | n/a |

| Turkey | Islam | Islam | 1928 |

| Uruguay | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1919 |

| Waldeck | Evangelical Church of Hesse-Kassel and Waldeck | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Wales[12] | Church in Wales | Anglican | 1920 |

| Württemberg | Evangelical Church of Württemberg | Lutheran | 1918 |

Notes

- ↑ "Theodosian Code XVI.i.2" (excerpt from Henry Bettenson, ed., Documents of the Christian Church. (London: Oxford University Press, 1943) at Paul Halsall.[1] Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. (June 1997) Fordham University Retrieved August 9, 2008

- ↑ John Madeley & Zsolt Enyedi, (eds.) Church and State in Contemporary Europe: the chimera of neutrality. (London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003)

- ↑ From the Meiji era to the first part of the Showa era in Japan, Koshitsu Shinto was established as the national religion. According to this, the emperor of Japan was an arahitogami, an incarnate divinity and the offspring of goddess Amaterasu. As the emperor was, according to the constitution, "head of the empire" and "supreme commander of the Army and the Navy," every Japanese citizen had to obey his will and show absolute loyalty until the end of World War II.

- ↑ Draft Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ (although president must always remain a Maronite Catholic, and prime minister a Sunni Muslim)

- ↑ (declared a secular state on May 18, 2006, by the newly resumed House of Representatives)

- ↑ Finland's State Church was the Church of Sweden until 1809. As an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia 1809-1917, Finland retained the Lutheran State Church system, and a state church separate from Sweden, later named the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, was established. It was detached from the state as a separate judicial entity when the new church law came to force in 1870. After Finland had gained independence in 1917, religious freedom was declared in the constitution of 1919 and a separate law on religious freedom in 1922. Through this arrangement, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland lost its position as a state church but gained a constitutional status as a national church alongside with the Finnish Orthodox Church, whose position however is not codified in the constitution.

- ↑ In France, the Concordat of 1801 made the Roman Catholic, Calvinist and Lutheran churches state-sponsored religions, as well as Judaism.

- ↑ In Hungary, the constitutional laws of 1848 declared five established churches on equal status: the Roman Catholic, Calvinist, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox and Unitarian Church. In 1868 the law was ratified again after the Ausgleich. In 1895 Judaism was also recognized as the sixth established church. In 1948 every distinction between the different denominations were abolished.

- ↑ Disestablished by the Philippine Organic Act of 1902.

- ↑ The Church of Scotland is "established" in the sense that its system of church courts was set up by Parliament, but over the centuries it has resisted interference by secular authorities. The Church of Scotland Act 1921 recognizes its exclusive authority to decide ecclesiastical issues, and the statute incorporates and accepts the Church's Declaratory Articles as lawful.

- ↑ The Church in Wales was split from the Church of England in 1920 by Welsh Church Act 1914; at the same time becoming disestablished.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berg, Thomas C. 2004. The State and Religion in a Nutshell. West Group Publishing. ISBN 978-0314148858

- Brown, L. Carl. 2001. Religion and State. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231120395

- Fox, Jonathan. 2008. A World Survey of Religion and the State. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521707589

- Hasson, Kevin Seamus. 2005. The Right to Be Wrong: Ending the Culture War Over Religion in America. Encounter Books. ISBN 1594030839

- Madeley, John & Zsolt Enyedi, eds. 2003. Church and State in Contemporary Europe: the chimera of neutrality. London: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 0714683299

- Weller, Paul. 2005. Time For A Change: Reconfiguring Religion, State And Society. London: T. & T. Clark. ISBN 978-0567084873

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.