North Korea

- For the history of Korea, see Korea.

| 조선민주주의인민공화국 Chosŏn Minjujuŭi Inmin Konghwaguk[1] Democratic People's Republic of Korea |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: 강성대국 (English: Powerful and Prosperous Nation), |

||||||

| Anthem: 애국가 (tr.: Aegukka) (English: The Patriotic Song) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Pyongyang 39°2′N 125°45′E | |||||

| Official languages | Korean | |||||

| Official scripts | Chosŏn'gŭl | |||||

| Ethnic groups | Korean | |||||

| Demonym | North Korean, Korean | |||||

| Government | Juche unitary single-party state | |||||

| - | Eternal President | Kim Il-sung[a] | ||||

| - | Supreme Leader (and NDC Chairman) |

vacant[b] | ||||

| - | Chairman of the Presidium | Kim Yong-nam[c] | ||||

| - | Premier | Choe Yong-rim | ||||

| Legislature | Supreme People's Assembly | |||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | Independence declared | March 1, 1919 | ||||

| - | Liberation | August 15, 1945 | ||||

| - | Formal declaration | September 9, 1948 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 120,540 km² (98th) 46,528 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 4.87 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2011 estimate | 24,457,492[2] (48th) | ||||

| - | 2008 census | 24,052,231[3] | ||||

| - | Density | 198.3/km² (55th) 513.8/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2008[4] estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $40 billion (94th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,900 (2009 est.)[2] (154th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2009[2] estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $28.2 billion (88th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,244[5] (139th) | ||||

| Gini (2009[6]) | N/A | |||||

| Currency | North Korean won (₩) (KPW) |

|||||

| Time zone | Korea Standard Time (UTC+9) | |||||

| Internet TLD | .kp | |||||

| Calling code | [[+850]] | |||||

| ^ a. Died 1994, named "Eternal President" in 1998. ^ b. Kim-Jong-un, described as "supreme leader of the party, state and army" by North Korean state media on December 29, 2011[7], was named Supreme Commander of the KPA on December 30, 2011 but has not yet succeeded to his father as Chairman of the NDC and General Secretary of the WPK.[8] |

||||||

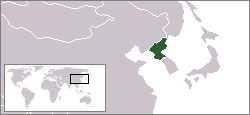

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (the DPRK), is an East Asian country in the northern half of the Korean Peninsula, with its capital in the city of Pyongyang. At its northern border are China on the Yalu River and Russia on the Tumen River, in the far northeastern corner of the country. To the south, it is bordered by South Korea, with which it formed one nation until the division following World War II.

History

- See also: History of Korea and Division of Korea

Emergence of North Korea

In the aftermath of the Japanese occupation of Korea, which ended with Japan's defeat in World War II in 1945, Korea was divided in two along the 38th parallel; the Soviet Union controlled the area north of the parallel and the United States controlled the area south of the parallel. Virtually all Koreans welcomed liberation from Japanese imperial rule, yet objected to re-imposition of foreign rule upon the peninsula. The Soviets and Americans disagreed on the implementation of Joint Trusteeship over Korea, with each imposing its socio-economic and political system upon its jurisdiction, leading, in 1948, to the establishment of ideologically opposed governments.[9] Growing tensions and border skirmishes between north and south led to the civil war called the Korean War.

On June 25, 1950 the (North) Korean People's Army crossed the 38th Parallel in a war of peninsular reunification under their political system. The war continued until July 27, 1953, when the United Nations Command, the Korean People's Army, and the Chinese People's Volunteers signed the Korean War Armistice Agreement. Since that time the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) has separated the North and South.

Economic evolution

In the aftermath of the Korean War and throughout the 1960s and '70s, the country's state-controlled economy grew at a significant rate and, until the late 1970s, was considered to be stronger than that of the South. The country struggled throughout the 1990s, primarily due to the loss of strategic trade arrangements with the USSR[10] and strained relations with China following China's normalization with South Korea in 1992.[11] In addition, North Korea experienced record-breaking floods (1995 and 1996) followed by several years of equally severe drought beginning in 1997.[12] This, compounded with only 18 percent arable land[13] and an inability to import the goods necessary to sustain industry,[14] led to an immense famine and left North Korea in economic shambles. Large numbers of North Koreans illegally entered the People's Republic of China in search of food. Faced with a country in decay, Kim Jong-il adopted a "Military-First" policy to strengthen the country and reinforce the regime.[15]

Geography

- See also: Korean Peninsula

North Korea is on the northern portion of the Korean Peninsula. North Korea shares land borders with China and Russia to the north, and with South Korea to the south. To its west are the Yellow Sea and Korea Bay, and to its east is the Sea of Japan. Japan lies east of the peninsula across the Sea of Japan.

The highest point in Korea is the Paektu-san at 2,744 meters (9,003 ft), and major rivers include the Tumen and the Yalu.

The local climate is relatively temperate, with precipitation heavier in summer during a short rainy season called changma, and winters that can be bitterly cold on occasion. North Korea's capital and largest city is P'yŏngyang; other major cities include Kaesŏng in the south, Sinŭiju in the northwest, Wŏnsan and Hamhŭng in the east and Ch'ŏngjin in the northeast.

Administrative divisions

- See also: Provinces of Korea and Special cities of Korea

North Korea is divided into nine provinces, three special regions, and two directly-governed cities (chikhalsi, 직할시, 直轄市):

| Province | Transliteration | Hangul | Hanja |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chagang | Chagang-do | 자강도 | 慈江道 |

| North Hamgyŏng | Hamgyŏng-pukto | 함경북도 | 咸鏡北道 |

| South Hamgyŏng | Hamgyŏng-namdo | 함경남도 | 咸鏡南道 |

| North Hwanghae | Hwanghae-pukto | 황해북도 | 黃海北道 |

| South Hwanghae | Hwanghae-namdo | 황해남도 | 黃海南道 |

| Kangwŏn | Kangwŏndo | 강원도 | 江原道 |

| North P'yŏngan | P'yŏngan-pukto | 평안북도 | 平安北道 |

| South P'yŏngan | P'yŏngan-namdo | 평안남도 | 平安南道 |

| Ryanggang | Ryanggang-do | 량강도 | 兩江道 |

* Sometimes rendered "Yanggang" (양강도).

| Region | Transliteration | Hangul | Hanja |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaesŏng Industrial Region | Kaesŏng Kong-ŏp Chigu | 개성공업지구 | 開城工業地區 |

| Kŭmgangsan Tourist Region | Kŭmgangsan Kwangwang Chigu | 금강산관광지구 | 金剛山觀光地區 |

| Sinŭiju Special Administrative Region | Sinŭiju T'ŭkpyŏl Haengjŏnggu | 신의주특별행정구 | 新義州特別行政區 |

| City | Transliteration | Hangul | Hanja |

|---|---|---|---|

| P'yŏngyang | P'yŏngyang Chikhalsi | 평양직할시 | 平壤直轄市 |

| Rasŏn (Rajin-Sŏnbong) | Rasŏn (Rajin-Sŏnbong) Chikhalsi | 라선(라진-선봉)직할시 | 羅先(羅津-先鋒)直轄市 |

Major cities

|

|

|

Government and politics

North Korea is a self-described Juche (self-reliant) socialist state,[16] described by some observers as a de facto absolute monarchy[17][18] or "hereditary dictatorship" with a pronounced cult of personality organized around Kim Il-sung (the founder of North Korea and the country's only president) and his son and heir, Kim Jong-il, and continuing with Kim Jong-Un, son of Kim Jong-Il.[19] Following Kim Il-sung's death in 1994, he was not replaced but instead received the designation of "Eternal President", and was entombed in the vast Kumsusan Memorial Palace in central Pyongyang; his song, Kim Jong-Il, is also to be enshrined there as the country's "eternal leader".[20]

Although the office of the President is ceremonially held by the deceased Kim Il-sung,[16] the Supreme Leader until his death in December 2011 was Kim Jong-il, who was General Secretary of the Workers' Party of Korea and Chairman of the National Defence Commission of North Korea. The legislature of North Korea is the Supreme People's Assembly.

The structure of the government is described in the Constitution of North Korea, the latest version of which is from 2009 and officially rejects North Korea's founding ideology as based on Communism while maintaining it is a socialist state; at the same time the revised constitution firmly placed power in the hands of Kim Jong-il as its “supreme leader” and made his “military first” policy its guiding ideology.[21][22] The governing party by law is the Democratic Front for the Reunification of the Fatherland, a coalition of the Workers' Party of Korea and two other smaller parties, the Korean Social Democratic Party and the Chondoist Chongu Party. These parties nominate all candidates for office and hold all seats in the Supreme People's Assembly.

In June 2009, it was reported in South Korean media that intelligence indicated that the country's next leader would be Kim Jong-un, the youngest of Kim Jong-il's three sons.[23] This was confirmed on December 19, 2011, following Kim Jong-il's death.[24][25]

Human rights

Multiple international human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, accuse North Korea of having one of the worst human rights records of any nation.[26] North Koreans have been referred to as "some of the world's most brutalized people" by Human Rights Watch, due to the severe restrictions placed on their political and economic freedoms.[27]

North Korean defectors have testified to the existence of prisons and concentration camps[28] with an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 inmates,[29] and have reported torture, starvation, rape, murder, medical experimentation, forced labor, and forced abortions.[30] Convicted political prisoners and their families are sent to these camps, where they are prohibited from marrying, required to grow their own food, and cut off from external communication.[31]

The system changed slightly at the end of 1990s, when population growth became very low. In many cases, capital punishment was replaced by less severe punishments. Bribery became prevalent throughout the country.[32] Today, many North Koreans now illegally wear clothes of South Korean origin, listen to Southern music, watch South Korean videotapes and even receive Southern broadcasts.[33][34]

Foreign relations

North Korea has long maintained close relations with the People's Republic of China and Russia. The fall of communism in eastern Europe in 1989, and the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, resulted in a devastating drop in aid to North Korea from Russia, although China continues to provide substantial assistance. North Korea continues to have strong ties with its socialist southeast Asian allies in Vietnam and Laos, as well as with Cambodia.[35] North Korea has started installing a concrete and barbed wire fence on its northern border, in response to China's wish to curb refugees fleeing from North Korea. Previously the border between China and North Korea had only been lightly patrolled.[36]

As a result of the North Korean nuclear weapons program, the Six-party talks were established to find a peaceful solution to the growing tension between the two Korean governments, the Russian Federation, the People's Republic of China, Japan, and the United States.

On July 17, 2007, United Nations inspectors verified the shutdown of five North Korean nuclear facilities, according to the February 2007 agreement.[37]

On October 4, 2007, South Korean President Roh Moo-Hyun and North Korean leader Kim Jong-il signed an 8-point peace agreement, on issues of permanent peace, high-level talks, economic cooperation, renewal of train, highway and air travel, and a joint Olympic cheering squad.[38]

The United States and South Korea previously designated the North as a state sponsor of terrorism.[39] The 1983 bombing that killed members of the South Korean government and the destruction of a South Korean airliner have been attributed to North Korea.[40] North Korea has also admitted responsibility for the kidnapping of 13 Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 1980s, five of whom were returned to Japan in 2002.[41] On October 11, 2008, the United States removed North Korea from its list of states that sponsor terrorism.[42]

In 2009, relationships between North and South Korea increased in intensity; North Korea had been reported to have deployed missiles,[43] ended its former agreements with South Korea,[44] and threatened South Korea and the United States not to interfere with a satellite launch it had planned.[45] North and South Korea are still technically at war (having never signed a peace treaty after the Korean War) and share the world’s most heavily fortified border.[46] On May 27, 2009, North Korean media declared that the Korean Armistice was no longer valid due to the South Korean government's pledge to "definitely join" the Proliferation Security Initiative.[citation needed] To further complicate and intensify strain between the two nations, the sinking of the South Korean warship Cheonan in March 2010, killing 46 seamen, is as of May 20, 2010 claimed by a multi-national research team[47] to have been caused by a North Korean torpedo, which the North denies. South Korea agreed with the findings from the research group and President Lee Myung-bak declared in May 2010 that Seoul would cut all trade with North Korea as part of measures primarily aimed at striking back at North Korea diplomatically and financially.[48] As a result of this, North Korea severed all ties, completely abrogated the previous pact of non aggression and expelled all South Koreans from a joint industrial zone in Kaesong.[49] On November 23, 2010, North Korea attacked Yeonpyeong Island, further deteriorating the diplomatic relations with the South and other nations.[50]

Most of the foreign embassies connecting with diplomatic ties to North Korea are situated in Beijing rather than Pyongyang.[51]

Since the cease fire of the Korean War in 1953, the North Korean government has been at odds with the United States, Japan, and South Korea (with whom it remains technically at war). North Korea's relations with the United States have become particularly tense in recent years. In 2002, U.S. President George W Bush labeled North Korea part of an "axis of evil" and an "outpost of tyranny." The highest-level contact the government has had with that of the United States was with U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who made a 2000 visit to Pyongyang; the countries do not have formal diplomatic relations. In 2006 approximately 37,000 American soldiers remained in South Korea, with plans to reduce this number to 25,000 by 2008.[52] Despite the frequent saber rattling, Kim Jong-il has frequently stated both privately and publicly his acceptance of U.S. troops on the peninsula even after a possible reunification.[53] The idea is that once North Korea and U.S. normalize relations, the presence of U.S. troops would have a stabilizing effect on the peninsula - particularly to assure Koreans of a checked Japan, following almost a half-century of colonialization.[53]

Two of the few ways to enter North Korea are over the Sino-Korea Friendship Bridge or via Panmunjeom, the former crossing the Amnok River and the latter crossing the Demilitarized Zone.

Both the North and South Korean governments proclaim that they are seeking eventual reunification as a goal. North Korea's policy is to seek reunification without what it sees as outside interference, through a federal structure retaining each side's leadership and systems. Both North and South Korea signed the June 15th North-South Joint Declaration in 2000, in which both sides made promises to seek out a peaceful reunification.

North Korea has maintained close relations with the People's Republic of China and the Russian Federation. The fall of communism in eastern Europe in 1989 and the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 resulted in a devastating drop in aid to North Korea from Russia, although China continues to provide substantial assistance. North Korea continues to have strong ties with its socialist Asian allies in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Military

North Korea is a highly militarized state. Annual military spending is estimated as high as $5 Billion USD (20% of GDP), compared with South Korea's $21.06 Billion USD (2.5% of GDP).[2] According to official North Korean media, military expenditures for national defense in 2010 amounted to 15.8 percent of the state budget.[54]

The Korean People's Army (KPA) is the name for the collective armed personnel of the North Korean military. It has five branches: Ground Force, Naval Force, Air Force, Special Operations Force, and Rocket Force. According to the U.S. Department of State, North Korea has the fourth-largest army in the world, at an estimated 1.21 million armed personnel, with about 20 percent of men aged 17–54 in the regular armed forces.[55] North Korea has the highest percentage of military personnel per capita of any nation in the world, with 49 military personnel for every 1,000 of its citizens.[56] Military conscription begins at age 17 and involves service for at least ten years, usually to age 30, followed by part-time compulsory service in the Workers and Peasants Red Guards until age 60.[57]

Military strategy is designed for insertion of agents and sabotage behind enemy lines in wartime,[55] with much of the KPA's forces deployed along the heavily fortified Korean Demilitarized Zone. The Korean People's Army operates a very large amount of military equipment,[57] as well as the largest special forces in the world.[58] In line with its asymmetric warfare strategy, North Korea has also developed a wide range of unconventional techniques and equipment.[59]

Nuclear weapons program

North Korea has active nuclear and ballistic missile weapons programs and has been subject to United Nations Security Council resolutions 1695 of July 2006, 1718 of October 2006, and 1874 of June 2009, for carrying out both missile and nuclear tests. Intelligence agencies and defense experts around the world agree that North Korea probably has the capability to deploy nuclear warheads on intermediate-range ballistic missiles with the capacity to wipe out entire cities in Japan and South Korea.[60]

Economy

In the aftermath of the Korean War and throughout the 1960s and '70s, the country's state-controlled economy grew at a significant rate and, until the late 1970s, was considered to be stronger than that of the South. State-owned industry produces nearly all manufactured goods. The government focuses on heavy military industry, following Kim Jong-il's adoption of a "Military-First" policy. Estimates of the North Korea economy cover a broad range, as the country does not release official figures and the secretive nature of the country makes outside estimation difficult. According to accepted estimates, North Korea spends $5 billion USD out of a Gross Domestic Product of $20.9 billion on the military, compared with South Korea's $15.49 billion out of a GDP of $852.74 billion.[61]

1990's Famine

In the 1990s North Korea faced significant economic disruptions, including a series of natural disasters, economic mismanagement, serious fertilizer shortages, and the collapse of the Soviet bloc. These resulted in a shortfall of staple grain output of more than 1 million tons from what the country needs to meet internationally-accepted minimum dietary requirements. The famine resulted in the deaths of between 300,000 and 800,000 North Koreans per year during the three year famine, peaking in 1997, with 2.0 million total being "the highest possible estimate."[62] The deaths were most likely caused by famine-related illnesses such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diarrhea rather than starvation.[62]

In 2006, Amnesty International reported that a national nutrition survey conducted by the North Korean government, the World Food Programme, and UNICEF found that 7 per cent of children were severely malnourished; 37 per cent were chronically malnourished; 23.4 per cent were underweight; and one in three mothers was malnourished and anaemic as the result of the lingering effect of the famine. The inflation caused by some of the 2002 economic reforms, including the "Military-first" policy, was cited for creating the increased price of basic foods.

Beginning in 1997, the U.S. began shipping food aid to North Korea through the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) to combat the famine. Shipments peaked in 1999 at nearly 700,000 tons making the U.S. the largest foreign aid donor to the country at the time. Under the Bush Administration aid was drastically reduced year over year from 350,000 tons in 2001 to 40,000 in 2004. The Bush Administration took criticism for using "food as a weapon" during talks over the North's nuclear weapons program, but insisted the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) criteria were the same for all countries and the situation in North Korea had "improved significantly since it's collapse in the mid-1990's." Agricultural production had increased from about 2.7 million metric tons in 1997 to 4.2 million metric tons in 2004.

Foreign Commerce

China and South Korea remain the largest donors of unconditional food aid to North Korea. The U.S. objects to this manner of donating food due to lack of oversight. In 2005, China and South Korea combined to provide 1 million tons of food aid, each contributing half. In addition to food aid, China reportedly provides an estimated 80 to 90 percent of North Korea's oil imports at "friendly prices" that are sharply lower than the world market price.[63]

On 19 September 2005, North Korea was promised fuel aid and various other non-food incentives from South Korea, the U.S., Japan, Russia, and China in exchange for abandoning its nuclear weapons program and rejoining the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Providing food in exchange for abandoning weapons programs has historically been avoided by the U.S. so as not to be perceived as "using food as a weapon". Humanitarian aid from North Korea's neighbors has been cut off at times to provoke North Korea to resume boycotted talks, such as South Korea's "postponed consideration" of 500,000 tons of rice for the North in 2006 but the idea of providing food as a clear incentive (as opposed to resuming "general humanitarian aid") has been avoided.[64]

In July 2002, North Korea started experimenting with capitalism in the Kaesŏng Industrial Region.[65] A small number of other areas have been designated as Special Administrative Regions, including Sinŭiju along the China-North Korea border. China and South Korea are the biggest trade partners of North Korea, with trade with China increasing 38% to $1.02 billion in 2003, and trade with South Korea increasing 12% to $724 million in 2003. It is reported that the number of mobile phones in P'yŏngyang rose from only 3,000 in 2002 to approximately 20,000 during 2004. As of June 2004, however, mobile phones became forbidden again. A small amount of capitalistic elements are gradually spreading from the trial area, including a number of advertising billboards along certain highways. Recent visitors have reported that the number of open-air farmers' markets has increased in Kaesong, P'yŏngyang, as well as along the China-North Korea border, bypassing the food rationing system.

In an event in 2003 dubbed the "Pong Su incident," a North Korean cargo ship allegedly attempting to smuggle heroin into Australia was seized by Australian officials, strengthening Australian and United States' suspicions that Pyongyang engages in international drug smuggling. The North Korean government denied any involvement.

Media and Telecommunications

Media

North Korean media are under some of the strictest government control in the world. The North Korean constitution provides for freedom of speech and the press; but the government prohibits the exercise of these rights in practice. In its 2010 report, Reporters without Borders ranked freedom of the press in North Korea as 177th out of 178, above only that of Eritrea.[66] Only news that favors the regime is permitted, while news that covers the economic and political problems in the country, and foreign criticism of the government, are not allowed.[67] The media upheld the personality cult of Kim Jong-il, regularly reporting on his daily activities.

The main news provider to media in the DPRK is the Korean Central News Agency. North Korea has 12 principal newspapers and 20 major periodicals, all of varying periodicity and all published in Pyongyang.[68] Newspapers include the Rodong Sinmun, Joson Inmingun, Minju Choson, and Rodongja Sinmum. No private press is known to exist.[67]

Telephones and Internet

North Korea has an adequate telephone system, with 1.18 million fixed lines available in 2008.[69] However, most phones are only installed for senior government officials. Someone wanting a phone installed must fill out a form indicating their rank, why he wants a phone, and how he will pay for it.[70]

Mobile phones were introduced into North Korea at the beginning of the twenty-first century, but then were banned for several years until 2008, when a new, 3G network, Koryolink, was built through a joint venture with Orascom Telecom Holding, of Egypt. By September 2010, the number of subscribers had reached 301,000.[71] By August 2011, the number of mobile-phone subscribers had increased to 660,000 users,[72] and by December 2011 the number of subscribers was reported as 900,000.[73]

North Korea's first Internet café opened in 2002 as a joint venture with a South Korean Internet company, Hoonnet. Ordinary North Koreans do not have access to the global Internet network, but are provided with a nationwide, public-use Intranet service called Kwangmyong, which features domestic news, an e-mail service, and censored information from foreign websites (mostly scientific).[74]

Transportation

Private cars in North Korea are a rare sight; as of 2008 some 70 percent of households used bicycles, which also play an increasingly important role in small-scale private trade.[75] Very few cars and light trucks are made in a joint-venture between Pyeonghwa Motors of South Korea, and the North Korean Ryonbong General Corp at a facility in Nampo North Korea.[76] Another local producer of vehicles is Sungri Motor Plant, which manufactures civilian vehicles and heavy trucks.

There is a mix of locally built and imported trolleybuses and trams in urban centers in North Korea. Earlier fleets were obtained in Europe and China, but the trade embargo has forced North Korea to build their own vehicles.

Rail transport

Choson Cul Minzuzui Inmingonghoagug (The Railways of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea) is the only rail operator in North Korea. It has a network of 5,200 km (3,200 mi) of track with 4,500 km (2,800 mi) in standard gauge. The network is divided into five regional divisions, all of which report into the Pyongyang headquarters.[77] The railway fleet consists of a mix of electric and steam locomotives. Initially transportation was by imported steam locomotives, the Juche philosophy of self-reliance led to electrification of the railways.[77]

People traveling from the capital Pyongyang to other regions in North Korea typically travel by rail. But in order to travel out of Pyongyang, people need an official travel certificate, ID, and a purchased ticket in advance. Due to lack of maintenance on the infrastructure and vehicles, the travel time by rail is increasing. It has been reported that the 120 mile (193 km) trip from Pyongyang to Kaesong can take up to 6 hours.[70]

In 2011 a train from the Russian border town of Khasan made an inaugural run to Rajin in North Korea. It run a 54-kilometer along a newly repaired link of reconstruction all the Trans-Korean rail for its further integration into the Trans-Siberian railroad.[78]

Marine transport

Water transport on the major rivers and along the coasts plays a growing role in freight and passenger traffic. Except for the Yalu and Taedong rivers, most of the inland waterways, totaling 2,253 kilometers (1,400 mi), are navigable only by small boats. Coastal traffic is heaviest on the eastern seaboard, whose deeper waters can accommodate larger vessels. The major ports are Chongjin, Haeju, Hungnam (Hamhung), Nampo, Senbong, Songnim, Sonbong (formerly Unggi), and Wonsan.[79] Nampo has increased in importance as a port since the 1990s.[80]

In the early 1990s, North Korea possessed an oceangoing merchant fleet, largely domestically produced, of sixty-eight ships (of at least 1,000 gross-registered tons), totaling 465,801 gross-registered tons (709,442 metric tons of deadweight (DWT)), which includes fifty-eight cargo ships and two tankers. There is a continuing investment in upgrading and expanding port facilities, developing transportation—particularly on the Taedong River—and increasing the share of international cargo by domestic vessels.

Air transport

There are 79 airports in North Korea, 37 of which are paved.[79] However, North Korea's international air connections are limited. There are regularly scheduled flights from the Sunan International Airport – 24 kilometers (15 mi) north of Pyongyang – to Moscow, Khabarovsk, Vladivostok, Bangkok, Beijing, Dalian, Kuala Lumpur, Shanghai, Shenyang along with seasonal services to Singapore and charter flights from Sunan to numerous Asian and European destinations including Tokyo and Nagoya. Regular charters to existing scheduled services are operated as per demand.[81] Internal flights are available between Pyongyang, Hamhung, Haeju, Kaesong, Kanggye, Kilju, Nampo, Sinuiju, Samjiyon, Wonsan, and Chongjin.

All civil aircraft are operated by Air Koryo: 38 aircraft in 2010, which were purchased from the Soviet Union and Russia. From 1976 to 1978, four Tu-154 jets were added to the 7 of propeller-driven An-24s and 2 Ilyushin Il-18s afterwards adding four long range Ilyushin Il-62M and three Ilyushin Il-76MD large cargo aircraft. In 2008 a long range Tupolev Tu-204-300 was purchased, and a larger version, the Tupolev Tu-204-100B, in 2010.[79]

Demographics

North Korea's population of roughly 24 million is one of the most ethnically and linguistically homogeneous in the world, with very small numbers of Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, and European expatriate minorities.

According to the CIA World Factbook, North Korea's life expectancy was 68.89 years in 2011, a figure roughly equivalent to that of Ukraine, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia, slightly lower than Iraq and Iran, and significantly lower than South Korea.[82] Infant mortality stood at a level of 27.11, which is 2.7 times higher than that of Russia and 6.5 times that of South Korea.[83]

Regarding mortality rate, North Korea appears ranked at the 76th place (with first place having the highest mortality rate), between Maldives (75th) and Cape Verde (77th).[83] North Korea's total fertility rate is relatively low and stood at 2.02 in 2011, comparable to those of the United States and France.[84]

Housing in North Korea is free, but cramped and often lacking amenities such as electric or central heating. Many families live in two-room apartment units. Comparatively small apartments are common in Asian nations, however. [85]

Language

North Korea shares the Korean language with South Korea. There are dialect differences within both Koreas, but the border between North and South does not represent a major linguistic boundary. While prevalent in the South, the adoption of modern terms from foreign languages has been limited in North Korea. Hanja (Chinese characters) are no longer used in North Korea (since 1949), although still occasionally used in South Korea. In South Korea, knowledge of Chinese writing is viewed as a measure of intellectual achievement and level of education. Both Koreas share the phonetic Hangul writing system, called Chosongul in North Korea. The official Romanization differs in the two countries, with North Korea using a slightly modified McCune-Reischauer system, and the South using the Revised Romanization of Korean.

Religion

Both Koreas share a Buddhist and Confucian heritage and a recent history of Christian and Cheondoism ("religion of the Heavenly Way") movements.

The North Korean constitution states that freedom of religion is permitted.[86] However, free religious activities no longer exist in North Korea, as the government sponsors religious groups only to create an illusion of religious freedom.[87][2]

According to Western standards of religion, the majority of the North Korean population would be characterized as irreligious. However, the cultural influence of such traditional religions as Buddhism and Confucianism still have an effect on North Korean spiritual life.[88]

Buddhists in North Korea reportedly fare better than other religious groups. They are given limited funding by the government to promote the religion, because Buddhism played an integral role in traditional Korean culture.[89]

Release International, an organization that supports persecuted Christians, has ranked North Korea as the country with the most severe persecution of Christians in the world.[90] Human rights groups such as Amnesty International also have expressed concerns about religious persecution in North Korea.

Pyongyang was the center of Christian activity in Korea until 1945. From the late forties 166 priests and other religious figures were killed or kidnapped (disappeared without trace), including Francis Hong Yong-ho, bishop of Pyongyang. No Catholic priest survived the persecution and all the churches were destroyed; since then only priests bringing aid have been permitted to enter North Korea.[91] Today, four state-sanctioned churches exist, which freedom of religion advocates say are showcases for foreigners.[92]

Education

Education in North Korea is free of charge, compulsory until the secondary level, and is controlled by the government.[93] The state also used to provide school uniforms free of charge until the early 1990s.[94] Compulsory education lasts eleven years, and encompasses one year of preschool, four years of primary education and six years of secondary education. The school curriculum has both academic and political content.[95]

Primary schools are known as people's schools, and children attend them from the age of 6 to 9. Then from age 10 to 16, they attend either a regular secondary school or a special secondary school, depending on their specialties.

Higher education is not compulsory in North Korea. It is composed of two systems: academic higher education and higher education for continuing education. The academic higher education system includes three kinds of institutions: universities, professional schools, and technical schools. Graduate schools for master's and doctoral level studies are attached to universities, and are for students who want to continue their education. Two notable universities in the DPRK are the Kim Il-sung University and Pyongyang University of Science and Technology, both in Pyongyang. The former, founded in October 1946, is an elite institution whose enrollment of 16,000 full- and part-time students in the early 1990s and is regarded as the "pinnacle of the North Korean educational and social system."[96]

North Korea is one of the most literate countries in the world, with an average literacy rate of 99 percent.[2]

Health care

North Korea has a national medical service and health insurance system.[97] Beginning in the 1950s, the DPRK put great emphasis on healthcare, and between 1955 and 1986, the number of hospitals grew from 285 to 2,401, and the number of clinics from 1,020 to 5,644.[98] There are hospitals attached to factories and mines. Since 1979 more emphasis has been put on traditional Korean medicine, based on treatment with herbs and acupuncture.

North Korea's healthcare system has been in a steep decline since the 1990s due to natural disasters, economic problems, and food and energy shortages. Many hospitals and clinics in North Korea now lack essential medicines, equipment, running water and electricity.[99]

Almost 100 percent of the population has access to sanitation and water, but it is not completely potable. Infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, have reached epidemic proportions. Among other health problems, many North Korean citizens suffer from the after effects of malnutrition, caused by famines related to the failure of its food distribution program and "military first" policy.[100]

Culture

North and South Korea traditionally share the culture of Korea, which has its beginnings 5000 years ago. Legends of the mythical founder of Korea, Dangun, influence Korean culture to this day as well as Shamanism, Buddhism, Daoism, Confucianism, and Christianity, all of which had profound impacts on the varied and colorful culture of both North and South Korea. Although the political separation of the two nations in the mid-twentieth century has created two distinct contemporary cultures, the common ground of their cultural histories remains evident.[101]

In July 2004, the Complex of Goguryeo Tombs became the first site in the country to be included in the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites.

Korean culture came under attack during the Japanese rule from 1910 to 1945. Japan enforced a cultural assimilation policy. During the Japanese rule, Koreans were encouraged to learn and speak Japanese, adopt the Japanese family name system and Shinto religion, and were forbidden to write or speak the Korean language in schools, businesses, or public places.[102] In addition, the Japanese altered or destroyed various Korean monuments including Gyeongbok Palace and documents which portrayed the Japanese in a negative light were revised.

Arts

Literature and arts in North Korea are state-controlled, mostly through the Propaganda and Agitation Department or the Culture and Arts Department of the Central Committee of the KWP.[103] Large buildings committed to culture have been built, such as the People's Palace of Culture or the Grand People's Palace of Studies, both in Pyongyang. Outside the capital, there is a major theater in Hamhung and in every city there are state-run theaters and stadiums.

A popular event in North Korea is the Grand Mass Gymnastics and Artistic Performance Arirang (Hangul: 아리랑 축제 Hanja: 아리랑 祝祭) or Arirang Festival. This two-month gymnastics and artistic festival celebrates the birthday of Kim Il-sung (April 15) and is held in Pyongyang. The Mass Games involve performances of dance, gymnastics, and choreographic routines which celebrate the history of North Korea and the Workers' Party Revolution.

North Korea employs over 1,000 artists to produce art for export at the Mansudae Art Studio in Pyongyang. Products include watercolors, ink drawings, posters, mosaics, and embroidery. Juche ideology asserts Korea's cultural distinctiveness and creativity as well as the productive powers of the working masses. Socialist realism is the approved style with North Korea being portrayed as prosperous and progressive and its citizens as happy and enthusiastic. Traditional Korean designs and themes are present most often in the embroidery. The artistic and technical quality of the works produced is very high but other than a few wealthy South Korean collectors there is a limited market due to public taste and reluctance of states and collectors to financially support the regime.[104]

Personality cult

The North Korean government exercises control over many aspects of the nation's culture, and this control has been used to perpetuate a cult of personality surrounding Kim Il-sung, and, to a lesser extent, Kim Jong-il. Music, art, and sculpture glorifies "Great Leader" Kim Il-sung and his son, "Dear Leader" Kim Jong-il.[105]

Kim Il-sung is still officially revered as the nation's "Eternal President." Several landmarks in North Korea are named for Kim Il-sung, including Kim Il-sung University, Kim Il-sung Stadium, and Kim Il-sung Square. Defectors have been quoted as saying that North Korean schools deify both father and son.[106]

Kim Jong-il's personality cult, although significant, was not as extensive as his father's. His birthday, like his father's, is one of the most important public holidays in the country. On Kim Jong-il's 60th birthday (based on his official date of birth), mass celebrations occurred throughout the country.[107]

Sports

The most well known sporting event in North Korea is the Mass Games that are the opening event of the annual Arirang Festival. The Mass Games are famed for the huge mosaic pictures created by more than 30,000 well-trained and disciplined school children, each holding up colored cards, accompanied by complex and highly choreographed group routines performed by tens of thousands of gymnasts and dancers.[108]

In football, fifteen clubs compete in the DPR Korea League level-one and vie for both the Technical Innovation Contests and the Republic Championship. The national football team, Chollima, compete in the Asian Football Confederation and are ranked 105 by FIFA as of May 2010. The team competed in the finals of the FIFA World Cup in 1966 and 2010.

In ice hockey, North Korea has a men’s team that is ranked 43rd out of 49[109] and competes in Division II. The women’s team is ranked 21 out of 34[110] and competes in Division II.

North Korea has been competing in the Olympic Games since 1964 and debuted at the summer games in 1972 by taking home five medals, including one gold. To date, North Korea has won medals in every summer Olympics in which they have participated. North Korea boycotted the 1988 Summer Olympics in neighboring Seoul in South Korea. At the Athens Games in 2004, the North and South marched together in the opening and closing ceremonies under the Unification Flag, but competed separately.

The martial art taekwondo originated in Korea. In the 1950s and 1960s, modern rules were standardized and taekwondo became an official Olympic sport in 2000. Other Korean martial arts include taekkyeon, hapkido, tang soo do, kuk sool won, kumdo, and subak.

See also

- List of Korea-related topics

- Korean War

Notes

- ↑ Administrative Population and Divisions Figures (#26) (PDF). DPRK: The Land of the Morning Calm. Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use (2003-04). Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Central Intelligence Agency, Korea, North World Factbook. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ↑ DPR Korea 2008 Population Census National Report. DPRK Central Bureau of Statistics (2009). Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ↑ Country Profile: North Korea. Foreign and Commonwealth Office, UK (2009-06-25). Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ↑ GDP (official exchange rate), The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, last updated on April 26, 2010; accessed on May 17, 2010. Population data obtained from Total Midyear Population, U.S. Census Bureau, International Data Base, accessed on May 17, 2010. Note: Per capita values were obtained by dividing the GDP (official exchange rate) data by the Population data.

- ↑ Korea, North. The United Nations Human Development Report (2009)). Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ↑ Sang-Hun, Choe, "New North Korean Leader Ascends to Head of Party", December 26, 2011.

- ↑ Associated Press, North Korea Names Kim Jong Un Supreme Commander ABC News (December 31, 2011). Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Establishment of the Republic of Korea". AsianInfo.org. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Prospects for trade with an integrated Korean market". Agricultural Outlook. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Why South Korea Does Not Perceive China to be a Threat". China in Transition. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ "An Antidote to disinformation about North Korea". Global Research. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ "North Korea Agriculture". Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Other Industry - North Korean Targets". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ "North Korea’s Military Strategy". Parameters, US Army War College Quarterly. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "DPRK's Socialist Constitution (Full Text)". The People's Korea (1998). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Young Whan Kihl and Hong Nack Kim (eds.), North Korea: The Politics of Regime Survival (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 2006, ISBN 978-0765616395), 56.

- ↑ Robert A. Scalapino and Chong-Sik Lee, Communism in Korea: The Society (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1973, ISBN 978-0520022744), 689.

- ↑ Mark Seddon, Last of the great ogres: As millions perished in gulags he feasted on caviar. But the death of Kim Jong Il leaves the nuclear state in the hands of his playboy son The Daily Mail Online (20th December 2011). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Associated Press, Kim Jong Il to be enshrined as "eternal leader" CBS News (January 12, 2012). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Jon Herskovitz and Christine Kim, North Korea drops communism, boosts "Dear Leaders" Reuters (Sep 28, 2009). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Choe Sang-hun, New North Korean Constitution Bolsters Kim’s Power The New York Times (September 28, 2009). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ N Korea 'names Kim's successor' BBC News (2 June 2009). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Rafael Wober, North Korea mourns Kim Jong Il; son is 'successor' Associated Press (December 19, 2011). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Alastair Gale, North Korea Leader Kim Jong Il Has Died The Wall Street Journal (December 18, 2011). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Amnesty International (2007). Our Issues, North Korea. Human Rights Concerns. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ Seok, Kay (2007-05-15). Grotesque indifference. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ Torture in North Korea: Concentration Camps in the Spotlight http://www.huffingtonpost.com/karin-badt/torture-in-north-korea-co_b_545254.html Retrieved October 08, 2010

- ↑ McDonald, Mark, "North Korean Prison Camps Massive and Growing", May 4, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ↑ Hawk, David (2003). The Hidden Gulag: Exposing North Korea’s Prison Camps – Prisoners' Testimonies and Satellite Photographs. U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Archived from the original on July 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ North Korea - Punishment and the Penal System, Library of Congress.

- ↑ Hagard, Stephen and Noland, Marcus Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 10-2 Economic Crime and Punishment in North Korea P. 16, March 2010 Retrieved 2010-05-28

- ↑ Yoon Il Geun, "South Korean Dramas Are All the Rage among North Korean People", The Daily NK, 2007-11-02.

- ↑ Lee Sung Jin, "North Korean People Copy South Korean TV Drama for Trade", The Daily NK, 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Kim Yong Nam Visits 3 ASEAN Nations To Strengthen Traditional Ties. The People's Korea (2001). Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ "Report: N. Korea building fence to keep people in", The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ CNN. "U.N. verifies closure of North Korean nuclear facilities", 2007-07-18. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedautogenerated3 - ↑ Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism. Country Reports on Terrorism: Chapter 3 — State Sponsors of Terrorism Overview. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ Washington Post. "Country Guide", The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ BBC. "N Korea to face Japan sanctions", BBC News, 2006-06-13. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ "U.S. takes North Korea off terror list", CNN, 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ "North Korea deploying more missiles", BBC News, 23 February 2009.

- ↑ "North Korea tears up agreements", BBC News, 30 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- ↑ "North Korea warning over satellite", BBC News, 3 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- ↑ "Koreas agree to military hotline – Jun 4, 2004", Edition.cnn.com, 2004-06-04. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- ↑ "Anger at North Korea over sinking", BBC News, 2010-05-20. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ Clinton: Koreas security situation 'precarious', by Matthew Lee, Associated Press, 24-05-2010

- ↑ Text from North Korea statement, by Jonathan Thatcher, Reuters, 25-05-2010

- ↑ "North Korea: a deadly attack, a counter-strike – now Koreans hold their breath", The Guardian, 23 November 2010.

- ↑ 北 수교국 상주공관, 평양보다 베이징에 많아. Yonhap News (2009-03-02). Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ "S. Korea to cut 40,000 troops by 2008". People's Daily Online. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "North Korea: Six-Party Talks Continue". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Korean Central News Agency, Report on Implementation of 2009 Budget and 2010 Budget Korea News Service (April 9, 2010). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 U.S. Department of State, Background Note: North Korea Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs (October 31, 2011). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Armied to the hilt The Economist (Jul 19th 2011). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Library of Congress Federal Research Division, Country Profile: North Korea, July 2007 National Security. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ James M. Minnich, Chapter 5. National Security North Korea: A Country Study (Library of Congress, Government Printing Office, 2008, ISBN 978-0844411880). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ New Threat from N.Korea's 'Asymmetrical' Warfare The Chosun Ilbo (English Edition) (Apr. 29, 2010). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Deirdre Hipwell, North Korea is fully fledged nuclear power, experts agree The Times (April 24, 2009). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Statistics. Icons Project. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Famine may have killed 2 million in North Korea. CNN. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ China's N.K. policy unlikely to change. Korea Herald. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ S. Korea Suspends Food Aid to North. Washington Post. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ North Korea to Let Capitalism Loose in Investment Zone. New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ↑ Reporters Without Borders, Press Freedom Index 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Ian Liston-Smith, "Meagre media for North Korea", BBC News (October 10, 2006). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Larinda B. Pervis, North Korea Issues: Nuclear Posturing, Saber Rattling, and International Mischief. (Nova Science Publishers, 2007, ISBN 978-1600216558), 22.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency, Country Comparison :: Telephones - main lines in use, The World Factbook. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Paul French, North Korea: The Paranoid Peninsula, A Modern History (New York, NY: Zed Books, 2005, ISBN 978-1842774731).

- ↑ Mobile phone subscriptions in N. Korea quadruple in one year: operator, YonhapNews (November 9, 2010). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Chris Green, Orascom User Numbers Keep Rising, DailyNK (August 11, 2011). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Hamish McDonald, Father knows best: son to maintain status quo, The Age (December 24, 2011). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Bertil Lintner, North Korea's IT revolution Asia Times (Apr 24, 2007). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Jung Kwon Ho, 70% of Households Use Bikes, The Daily NK (2008-10-30). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Pyeonghwa Motors, China's Brilliance in Talks to Product Trucks AsiaPulse News (August 1, 2007). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Rob Dickinson, Steam in North Korea 2002 The International Steam Pages. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ AFP, Russian train travels to N. Korea along repaired link The Strait Times (Oct 13, 2011). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 PHP Classes, Traveling to North Korea About North Korea. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Jin-Cheol Jo and César Ducruet, Maritime Trade and Port Evolution in a Socialist Developing Country: Nampo, Gateway of North Korea Planning Review 51(12) (2006): 3-24. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ D. Swede, Getting into DPRK North Korea Transportation, Virtual Tourist. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency, Country Comparison :: Life expectancy at birth The World Factbook. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Central Intelligence Agency, Country Comparison :: Infant mortality rate The World Factbook. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency, Country Comparison :: Total Fertility Rate The World Factbook. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Carl Haub, North Korea Census Reveals Poor Demographic and Health Conditions, Population Reference Bureau (December 2010). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ The People's Korea, DPRK's Socialist Constitution (Full Text) (1998) see Chapter 5, Article 68. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch, Human Rights in North Korea Human Rights Overview (July 2004). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State, Background Note: North Korea Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs (October 31, 2011). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Barbara Demick, Temple Being Restored in N. Korea Los Angeles Times (October 02, 2005). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Religious Intelligence, North Korea ‘is world’s most dangerous place for Christians’ January 5, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Gianni Cardinale, Korea, for a reconciliation between North and South Interview with Cardinal Nicholas Cheong Jinsuk 30 Days (2006). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ N Korea stages Mass for Pope BBC News (10 April, 2005). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Library of Congress, North Korea: Education Overview, Library of Congress Country Studies (June 1993). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Min Cho Hee, Political Life Launched by Chosun Children's Union Daily NK (2009). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Library of Congress, North Korea: Primary and Secondary education Library of Congress Country Studies (June 1993). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Library of Congress, North Korea – Higher education Library of Congress Country Studies (June 1993). Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Library of Congress, Country Profile - North Korea, Library of Congress Country Profile (July 2007) see p. 8 - Health. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Country Studies, Public Health, North Korea (June 29, 1994). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Caroline Gluck, N Korea healthcare 'near collapse' BBC News (20 November, 2001). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Amnesty International, The Crumbling State of Healthcare in North Korea (London: Amnesty International Publications, 2010). Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ↑ Kim Hyun, Same roots, different style, Korea Is One (July 4, 2006). Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ Bruce G. Cumings, The Rise of Korean Nationalism and Communism Chapter 1 - Historical Setting A Country Study: North Korea (Library of Congress, 2009). Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ Donald M. Seekins, Contemporary Cultural Expression, Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment, A Country Study: North Korea (The Library of Congress, 2009). Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ Leonid Petrov, Pyongyang’s Idealistic Art Impresses the Realist-minded Moscow NK News (February 3, 2011). Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ Bradley K. Martin, Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty (New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin, 2006, ISBN 978-0312323226).

- ↑ Chol-hwan Kang and Pierre Rigoulot, The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag (Basic Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0465011049).

- ↑ North Korea marks leader's birthday BBC (16 February 2002). Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ Jonathan Watts, Welcome to the strangest show on earth The Guardian (1 October 2005). Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ↑ 2010 Men's World Ranking. International Ice Hockey Federation. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ↑ 2010 Women's World Ranking. International Ice Hockey Federation. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- French, Paul. North Korea: The Paranoid Peninsula, A Modern History. New York, NY: Zed Books, 2005. ISBN 978-1842774731

- Kang, Chol-hwan, and Pierre Rigoulot. The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag. Basic Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0465011049

- Martin, Bradley K. Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty. New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin, 2006. ISBN 978-0312323226

- Pervis, Larinda B. North Korea Issues: Nuclear Posturing, Saber Rattling, and International Mischief. Nova Science Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978-1600216558

- Chang, Gordon G. 2006. Nuclear showdown: North Korea takes on the world. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 9781400062942.

- Cumings, Bruce. 2003. North Korea: another country. New York, NY: New Press. ISBN 9781565848733.

- Miller, Debra A. 2004. North Korea. World's hot spots. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. ISBN 9780737722956.

- Becker, Jasper. 2005. Rogue Regime: Kim Jong Il and the Looming Threat of North Korea. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195170443.

- Cucullu, Gordon. 2004. Separated At Birth: How North Korea Became The Evil Twin. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press. ISBN 1-59228-591-0.

- Cumings, Bruce. 1998. Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31681-5.

- Cumings, Bruce. 1981. Origins of the Korean War (Vol. 1): Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes 1945-1947. Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-10113-2

- Cumings, Bruce. 2004. Origins of the Korean War (Vol. 2): The Roaring of the Cataract 1947-1950. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 89-7696-613-9.

- Cumings, Bruce. 2004. North Korea: Another Country. New York, NY: New Press ISBN 1-56584-940-X.

- Cumings, Bruce. 2004. Living Through The Forgotten War: Portrait Of Korea. Middleton, CT: Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies. ISBN 0-9729704-0-1.

- Cumings, Bruce. 2006. Inventing the Axis of Evil: The Truth About North Korea, Iran, and Syria. New York, NY: New Press. ISBN 1-59558-038-7.

- Delisle, Guy. 2005. Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea. Montréal, CA: Drawn & Quarterly Books. ISBN 1-896597-89-0.

- Eberstadt, Nick. 1999. The End of North Korea. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute Press. ISBN 0-8447-4087-X

- Feffer, John. 2003. North Korea South Korea: U.S. Policy at a Time of Crisis. New York, NY: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1-58322-603-6.

- Harrold, Michael. 2004. Comrades and Strangers: Behind the Closed Doors of North Korea. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing. ISBN 0-470-86976-3.

- Hunter, Helen-Louise. 1999. Kim Il-song's North Korea. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96296-2.

- Kang, Chol-Hwan. 2001. The Aquariums of Pyongyang. New York, NY: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-01102-0.

- Lerner, Mitchell B. 2002. The Pueblo Incident: A Spy Ship and the Failure of American Foreign Policy. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1171-1.

- Martin, Bradley. 2004. Under The Loving Care Of The Fatherly Leader: North Korea And The Kim Dynasty. New York, NY: St. Martins. ISBN 0-312-32221-6.

- Oberdorfer, Don. 1997. The two Koreas : a contemporary history. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-40927-5.

- Kong Dan Oh, and Ralph C. Hassig. 2000. North Korea Through the Looking Glass. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. ISBN 0-8157-6435-9.

- Quinones, C. Kenneth, and Joseph Tragert. 2004. The Complete Idiot's Guide to Understanding North Korea. Indianapolis, IN: Alpha Books. ISBN 1-59257-169-7.

- Sigal, Leon V. 1998. Disarming Strangers: Nuclear Diplomacy with North Korea. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05797-4.

- Springer, Chris. 2003. Pyongyang: The Hidden History of the North Korean Capital. Gold River, CA: Saranda Books. ISBN 963-00-8104-0.

- Vladimir. 2003. Cyber North Korea. Tokyo, JP: Byakuya Shobo. ISBN 4-89367-881-7.

- Vollertsen, Norbert. 2003. Inside North Korea: Diary of a Mad Place. New York, NY: Encounter Books. ISBN 1-893554-87-2.

- Wahn Kihl, Y. 1983. North Korea in 1983: Transforming "The Hermit Kingdom? Asian Survey. 24:1:100-111.

- Willoughby, Robert. 2003. North Korea: The Bradt Travel Guide. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot. ISBN 1-84162-074-2.

- Kim, Hyun Hee. 1993. The Tears of My Soul. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, Inc. ISBN 0-688-12833-5.

External links

All links retrieved January 4, 2012.

- A Country Study: North Korea The Library of Congress

- North Korea The World Factbook

- North Korea International Documentation Project

- North Korea country profile BBC News

- Korean Central News Agency official news agency of the DPRK

- Official webpage of The Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK)

- North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea - DPRK) Online resources, University of Colorado Boulder

- Inside North Korea: New Year & Xmas Celebrations NK News

- Naenara

- Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries

- Korea Education Fund

- Korean Central News Agency

- In pictures: Inside North Korea The First Post

- Inside North Korea Life magazine

- A Year in Pyongyang by Andrew Holloway

- Korea is One!

- Pyongyang Watch by Aidan Foster-Carter

- Daily NK North Korea focused daily online newspaper

- Kim's Nuclear Gamble PBS Frontline Documentary (Video & Transcript).

- Seoul Train Documentary on North Koreans Trying to escape via China 2004.

- A State of Mind Documentary by the BBC following two young North Korean gymnasts training for the mass games (2004).

- One Free Korea Updated daily; focusing on human rights, political, economic, and military issues, often with Google-Earth tours of North Korea's most secret places.

- 1stopKorea.com

- In pictures: Unseen North Korea BBC News

- North Korea - Countries and Their Cultures

| SARs | |||

Sometimes included: Singapore · Vietnam · Russian Far East

Afghanistan · Armenia · Azerbaijan1 · Bahrain · Bangladesh · Bhutan · Brunei · Cambodia · China, People's Republic of · China, Republic of (Taiwan)2 · Cyprus · Egypt3 · Georgia1 · India · Indonesia4 · Iran · Iraq · Israel · Japan · Jordan · Kazakhstan1 · Korea, Democratic People's Republic of · Korea, Republic of · Kuwait · Kyrgyzstan · Laos · Lebanon · Malaysia · Maldives · Mongolia · Myanmar · Nepal · Oman · Pakistan · Philippines · Qatar · Russia1 · Saudi Arabia · Singapore · Sri Lanka · Syria · Tajikistan · Thailand · Timor-Leste (East Timor)4 · Turkey1 · Turkmenistan · United Arab Emirates · Uzbekistan · Vietnam · Yemen3

For dependent and other territories, see Dependent territory and List of unrecognized countries.

1 Partly or significantly in Europe.

2 The Republic of China (Taiwan) is not officially recognized by the United Nations; see Political status of Taiwan.

3 Partly or significantly in Africa.

4 Partly or wholly reckoned in Oceania.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.