Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- This article is about the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas. For details of those inhabitants of the United States of America, see Native Americans in the United States.

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Americas, their descendants, and many ethnic groups who identify with those peoples. They are often also referred to as "Native Americans" or "American Indians," although such terms are also commonly applied to those tribes who inhabit what is now the United States.

The word "Indian" was an invention of Christopher Columbus, who erroneously thought that he had arrived in the East Indies. The misnomer remains, and has served to imagine a kind of racial or cultural unity for the autochthonous peoples of the Americas. The unitary idea of "Indians" was not one shared by most indigenous peoples, who saw themselves as diverse. But the "Indian" gave Europeans a fixed person who could be labeled (as "primitive" or "heathen," for example), given a legal designation, and classified. Thus, the word "Indian" gave Europeans a valuable tool for colonization. Today, many native peoples have proudly embraced an imagined spiritual, ethnic, or cultural unity of "Indians."

According to the New World migration model which has near-universal support among the scientific community, a migration of humans from Eurasia to the Americas took place via Beringia, a land bridge which formerly connected the two continents across what is now the Bering Strait. The minimum time depth by which this migration had taken place is confirmed at c. 12,000 years ago, with the upper bound (or earliest period) remaining a matter of some unresolved contention.[2] These early Paleoamericans soon spread throughout the Americas, diversifying into many hundreds of culturally distinct nations and tribes.[3]

According to the oral histories of many of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, they have been living there since their genesis, described by a wide range of traditional creation accounts.

Some indigenous peoples of the Americas supported agriculturally advanced societies for thousands of years. In some regions they created large sedentary chiefdom polities, and had advanced state level societies with monumental architecture and large-scale, organized cities. The impact of their agricultural endowment to the world is a testament to their time and work in reshaping, taming and cultivating the flora and fauna indigenous to the Americas.[4]

History

Original peopling of the Americas

Scholars who follow the Bering Strait theory agree that most indigenous peoples of the Americas descended from people who probably migrated from Siberia across the Bering Strait, anywhere between 9,000 and 50,000 years ago. The timeframe and exact routes are still matters of debate, and the model faces continuous challenges.

A 2006 study (to be published in Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology) reports new DNA-based research that links DNA retrieved from a 10,000-year-old fossilized tooth from an Alaskan island, with specific coastal tribes in Tierra del Fuego, Ecuador, Mexico, and California.[5] Unique DNA markers found in the fossilized tooth were found only in these specific coastal tribes, and were not comparable to markers found in any other indigenous peoples in the Americas. This finding lends substantial credence to a migration theory that at least one set of early peoples moved south along the west coast of the Americas in boats. However, these results may be ambiguous, as there are other issues with DNA research and biological and cultural affiliation as outlined in Peter N. Jones' book Respect for the Ancestors: Cultural Affiliation and Cultural Continuity in the American West.

One result of these waves of migration is that large groups of peoples with similar languages and perhaps physical characteristics as well, moved into various geographic areas of North, and then Central and South America. While these peoples have traditionally remained primarily loyal to their individual tribes, ethnologists have variously sought to group the myriad of tribes into larger entities which reflect common geographic origins, linguistic similarities, and lifestyles.[6]

Remnants of a human settlement in Monte Verde, Chile dated to 12,500 years B.P. (another layer at Monteverde has been tentatively dated to 33,000-35,000 years B.P.) suggests that southern Chile was settled by peoples who entered the Americas before the peoples associated with the Bering Strait migrations. It is suggested that a coastal route via canoes could have allowed rapid migration into the Americas.

The traditional view of a relatively recent migration has also been challenged by older findings of human remains in South America; some dating to perhaps even 30,000 years old or more. Some recent finds (notably the Luzia skeleton in Lagoa Santa, Brazil) are claimed to be morphologically distinct from Asians and are more similar to African and Australian Aborigines. These American Aborigines would have been later displaced or absorbed by the Siberian immigrants. The distinctive Fuegian natives of Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of the American continent, are speculated to be partial remnants of those Aboriginal populations.

These early immigrants would have either crossed the ocean by boat or traveled north along the Asian coast and entered America through the Northwest, well before the Siberian waves. This theory is presently viewed by many scholars as conjecture, as many areas along the proposed routes now lie underwater, making research difficult.

Scholars' estimates of the total population of the Americas before European contact vary enormously, from a low of 10 million to a high of 112 million.[7] Whatever the figure, scholars generally agree that most of the indigenous population resided in Mesoamerica and South America, while about 10 percent resided in North America.[8]

European colonization

The European invasion of the Americas forever changed the lives, bloodlines and cultures of the peoples of the continent. Their populations were ravaged by disease, by the privations of displacement, and in many cases by warfare with European groups that may have tried to enslave them. The first indigenous group encountered by Columbus were the 250,000 Tainos of Hispaniola who were the dominant culture in the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. Later explorations of the Caribbean led to the discovery of the Aruak peoples of the lesser Antilles. Whoever wasn't killed by the widespread diseases brought in from Europe or the many conflicts against European soldiers were enslaved, and the culture was extinct by 1650. Only 500 had survived by the year 1550, though the bloodlines continued through the modern populace. In Amazonia, indigenous societies weathered centuries of unforgiving colonial affronts[9]

The Spaniards and other Europeans brought horses to the Americas. Some of these animals escaped and began to breed and increase their numbers in the wild. Interestingly, the horse had originally evolved in the Americas, but the last American horses (species Equus scotti and others died out at the end of the last ice age with other megafauna.[10] The suggestion that these extinctions, contemporary with a general late Pleistocene extinction throughout the globe, was due to overhunting by native Americans is fairly unlikely, given the overwhelming evidence for some type of natural catastrophe as the culprit. The re-introduction of the horse had a profound impact on Native American culture in the Great Plains of North America and of Patagonia in South America. This new mode of travel made it possible for some tribes to greatly expand their territories, exchange many goods with neighboring tribes, and more easily capture game.

Europeans also brought diseases against which the indigenous peoples of the Americas had no immunity. Chicken pox and measles, though common and rarely life-threatening among Europeans, often proved fatal to the indigenous people, and more dangerous diseases such as smallpox were especially deadly to indigenous populations. Epidemics often immediately followed European exploration sometimes destroying entire villages. It is difficult to estimate the total percentage of the indigenous population killed by these diseases, but some historians estimate that up to 80 percent of some indigenous populations may have died due to European diseases.[11]

Smallpox, typhus, influenza, diphtheria, measles, malaria, and other epidemics swept in after European contact, felling a large portion of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, causing one of the greater calamities in human history,[12] comparable only to the Black Death. In North America alone, at least 93 waves of epidemic disease swept through native populations between first contact and the early 20th century.[13] Another reason for the dramatic decline of the Native American population were the continuing wars with either Europeans or between feuding indigenous communities. More recently, collective mobilization among the indigenous peoples in the Americas has required the incorporation of closely-knit local communities into a broader national and international framework of political action.

Agricultural endowment

Over the course of thousands of years, a large array of plant species were domesticated, bred and cultivated by the indigenous peoples of the American continent. This American agricultural endowment to the world now constitutes more than half of all crops grown worldwide [14]. In certain cases, the indigenous peoples developed entirely new species and strains through artificial selection, as was the case in the domestication and breeding of maize from wild teosinte grasses in the valleys of southern Mexico. Maize alone now accounts in gross tonnage for the majority of all grain produced world-wide[citation needed]. A great number of these agricultural products still retain native names (Nahuatl and others) in the English and Spanish lexicons.

Some indigenous American agricultural products that are now produced and/or used globally include:

- Maize(corn), (domesticated from teosinte grasses in southern Mexico starting 12000 years ago; maize, squash and beans form the indigenous triumvirate crop system known as the "three sisters")

- Squash (pumpkins, zucchini, marrow, acorn squash, butternut squash, others)

- Pinto bean (Frijol pinto) ("painted/speckled" bean; nitrogen-fixer traditionally planted in conjunction with other "two sisters" to help condition soil; runners grew on maize; beans in the genus Phaseolus including most common beans, tepary beans and lima beans were also all first domesticated and cultivated by indigenous peoples in the Americas)

- Tomato

- Potato

- Avocado

- Peanuts

- Cacao* beans (used to make chocolate)

- Vanilla

- Strawberry (various cultivars; modern Garden strawberry was created by crossing sweet North American variety with plump South American variety)

- Pineapple (cultivated extensively)

- Peppers (species and varieties of Capsicum, including bell peppers, jalapeños, paprika, chili peppers, now used in world-wide cuisines.)

- Sunflower seeds (under cultivation in Mexico and Peru for thousands of years; also source of essential oils)

- Rubber (used indigenously for making bouncing balls, foot-molded rubber shoes, and other assorted items)

- Chicle (also known as chewing gum)

- Cotton (cultivation of different species independently started in both the Americas and in India)

- Tobacco (ceremonial entheogen; leaves smoked in pipes)

- Coca (leaves chewed for energy and medicinal uses)

(* Asterisk indicates a common English or Spanish word derived from an indigenous word)

Culture

No single cultural trait can be said to be unifying or definitive for all of the peoples of the Americas. Spanning all climate zones and most technological levels, several thousand distinct cultural patterns have existed among the peoples of the Americas. Cultural practices in the Americas seem to have been mostly shared within geographical zones where otherwise unrelated peoples might adopt similar technologies and social organisations. An example of such a cultural area could be Mesoamerica, where millennia of coexistence and shared development between the peoples of the region produced a fairly homogeneous culture with complex agricultural and social patterns. Another well-known example could be the North American plains area, where until the 19th century, several different peoples shared traits of nomadic hunter-gatherers primarily based on buffalo hunting. Within the Americas, dozens of larger and hundreds of smaller culture areas can be identified.

Music and art

Native American music in North America is almost entirely monophonic, but there are notable exceptions. Traditional Native American music often includes drumming but little other instrumentation, although flutes are played by individuals. The tuning of these flutes is not precise and depends on the length of the wood used and the hand span of the intended player, but the finger holes are most often around a whole step apart and, at least in Northern California, a flute was not used if it turned out to have an interval close to a half step.

Music from indigenous peoples of Central Mexico and Central America often was pentatonic. Before the arrival of the Spaniards it was inseparable from religious festivities and included a large variety of percussion and wind instruments such as drums, flutes, sea snail shells (used as a kind of trumpet) and "rain" tubes. No remnants of pre-Columbian stringed instruments were found until archaeologists discovered a jar in Guatemala, attributed to the Maya of the Late Classic Era (600-900 C.E.), which depicts a a stringed musical instrument which has since been reproduced. This instrument is astonishing in at least two respects. First, it is the only stringed instrument known in the Americas prior to the introduction of European musical instruments. Second, when played, it produces a sound virtually identical to a jaguar's growl. A sample of this sound is available at the Princeton Art Museum website.

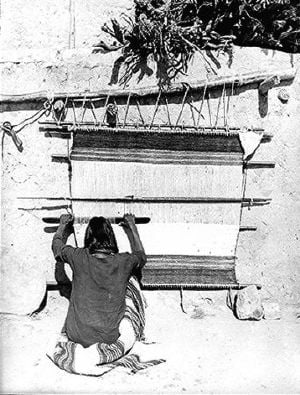

Art of the indigenous peoples of the Americas comprises a major category in the world art collection. Contributions include pottery, paintings, jewellery, weavings, sculptures, basketry,carvings and hair pipes.

Modern statistics on indigenous populations

The following table provides estimates of the per-country populations of indigenous people, and also those with part-indigenous ancestry, expressed as a percentage of the overall country population. of each country that is comprised by indigenous peoples, and of people with partly indigenous descent. The total percentage obtained by adding both of these categories is also given (One should note however that these categories, especially the second one, are inconsistently defined and measured differently from country to country).

| Country | Indigenous | Part-indigenous | Combined total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | .9 percent | 4 percent | 5 percent |

| Bolivia | 55 percent | 30 percent | 85 percent |

| Brazil² | 0.4 percent | [?] | [?] |

| Canada³ | 1.9 percent4 | 2.7 percent | 4.6 percent |

| Chile | 3 percent | 60 - 72 percent | 75 percent |

| Colombia | 3,4 percent5 | 82,1 percent | 85,5 percent6 |

| Costa Rica7 | 1 percent | [?] | [?] |

| Cuba7 | 1 percent | NA | NA |

| Dominican Republic | 1 percent | 40-60 percent | 41-61 percent |

| Guatemala | 40 percent | 45 percent | 85 percent |

| Ecuador | 25 percent | 55 percent | 80 percent |

| El Salvador | 1 percent | 90 percent | 91 percent |

| French Guiana, Guyana and Suriname |

5 – 20 percent | [?] | [?] |

| Honduras | 7 percent | 90 percent | 97 percent |

| Mexico | 30 percent8 | 60 percent | 90 percent |

| Nicaragua | 5 percent | 69 percent | 74 percent |

| Panama | 6 percent | 70 percent | 76 percent |

| Paraguay | 5 percent | 93.3 percent | 98.3 percent |

| Peru | 45 percent | 37 percent | 82 percent |

| Puerto Rico | 0.4 percent | 61.2 percent | 61.6 percent9] |

| Venezuela | 2 percent | 69 percent | 71 percent |

| USA10 | 2 percent | 5 percent | 7 percent |

| Uruguay | 0 percent | 8 percent | 8 percent |

|

1 Source : The World Factbook 1999, Central Intelligence Agency unless otherwise indicated. | |||

History and status by country

Argentina

Argentina's indigenous population is about 403.000 (0,9 percent of total population).[16] Indigenous nations include the Toba, Wichí, Mocoví, Pilagá, Chulupí, Diaguita-Calchaquí, Kolla, Guaraní (Tupí Guaraní and Avá Guaraní in the provinces of Jujuy and Salta, and Mbyá Guaraní in the province of Misiones), Chorote, Chané, Tapieté, Mapuche, Tehuelche and Selknam (Ona).

Belize

Mestizos (European with indigenous peoples) number about 45 percent of the population; unmixed Maya make up another 6.5 percent. The Garifuna, who came to Belize in the 1800s, originating from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, with a mixed African, Carib, and Arawak ancestery, take up another 5% of the population.

Bolivia

In Bolivia about 2.5 million people speak Quechua, 2.1 million speak Aymara, while Guaraní is only spoken by a few hundred thousand people. The languages are recognized; nevertheless, there are no official documents written in those languages and people who do not speak the only official language Spanish are badly treated[citation needed]. However, the constitutional reform in 1997 for the first time recognized Bolivia as a multilingual, pluri-ethnic society and introduced education reform. In 2005, for the first time in the country's history, an indigenous Aymara president, Evo Morales, was elected.

Brazil

The Indigenous peoples in Brazil (povos indígenas in Portuguese) comprise a large number of distinct ethnic groups who inhabited the country's present territory prior to its discovery by Europeans around 1500. Unlike Christopher Columbus, who thought he had reached the East Indies, the Portuguese had already reached India via the Indian Ocean route when they reached Brazil. Nevertheless the word índios ("Indians"), was by then established to designate the peoples of the New World and stuck still being used today in Brazil.

At the time of European discovery, the indigenous peoples were traditionally mostly semi-nomadic tribes who subsisted on hunting, fishing, gathering, and migrant agriculture. Many of the estimated 2000 nations and tribes which existed in 1500 died out as a consequence of the European settlement, and many were assimilated into the Brazilian population. The indigenous population has declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated at below 4 million to some 300,000 (1997), grouped into some 200 tribes. A somewhat dated linguistic survey [17] found 188 living indigenous languages with 155,000 total speakers. On 18 January 2007, FUNAI reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. With this addition Brazil has now overtaken the island of New Guinea as the country having the largest number of uncontacted peoples.

Brazilian indigenous people made substantial and pervasive contributions to the country's material and cultural development—such as the domestication of cassava, which is still a major staple food in rural areas of the country.

In the last IBGE census (2000), 700,000 Brazilians classified themselves as indigenous.

Origins

The origins of these indigenous peoples are still a matter of dispute among archaeologists. The traditional view, which traces them to Siberian migration to America at the end of the last ice age, has been increasingly challenged by South American archaeologists.

The Siberian Ice Age hypothesis

Anthropological and genetic evidence indicates that most Native American peoples descended from migrant peoples from North Asia (Siberia) who entered America across the Bering Strait in at least three separate waves. In Brazil, particularly, most native tribes who were living in the land by 1500 are thought to be descended from the first wave of migrants, who are believed to have crossed the so-called Bering Land Bridge at the end of the last Ice Age, around 9000 B.C.E.

A migrant wave around 9000 B.C.E. would have reached Brazil around 6000 B.C.E., probably entering the Amazon River basin from the Northwest. (The second and third migratory waves from Siberia, which are thought to have generated the Athabaskan and Eskimo peoples, apparently did not reach farther than the southern United States and Canada, respectively.)

The American Aborigines hypothesis

The traditional view above has recently been challenged by findings of human remains in South America, which are claimed to be too old to fit this scenario—perhaps even 20,000 years old. Some recent finds (notably the Luzia skeleton in Lagoa Santa) are claimed to be morphologically distinct from the Asian genotype and are more similar to African and Australian Aborigines. These American Aborigines would have been later displaced or absorbed by the Siberian immigrants. The distinctive natives of Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of the American continent, may have been the last remains of those Aboriginal populations.

These early immigrants would have either crossed the ocean on boat, or traveled North along the Asian coast and entered America through the Bering Strait area, well before the Siberian waves. This theory is still resisted by many scientists chiefly because of the apparent difficulty of the trip.

Archaeological remains

Virtually all the surviving archaeological evidence about the pre-history of Brazil dates from the period after the Asian migratory waves. Brazilian natives, unlike those in Mesoamerica and the western Andes, did not keep written records or erect stone monuments, and the humid climate and acidic soil have destroyed almost all traces of their material culture, including wood and bones. Therefore, what is known about the region's history before 1500 has been inferred and reconstructed from small-scale archaeological evidence, such as pottery and stone arrowheads.

The most conspicuous remains of pre-discovery societies are very large mounds of discarded shellfish (sambaquís) found in some coastal sites which were continuously inhabited for over 5,000 years; and the substantial "black earth" (terra preta) deposits in several places along the Amazon, which are believed to be ancient garbage dumps (middens). Recent excavations of such deposits in the middle and upper course of the Amazon have uncovered remains of some very large settlements, containing tens of thousands of homes, indicating a complex social and economical structure.

The natives after the European colonization

First contacts

When the Portuguese discoverers arrived for the first time in Brazil, in April 1500 they found, to their astonishment, a widely inhabited coastland, teeming with hundreds of thousands of indigenous people living in a "paradise" of natural riches. Pero Vaz de Caminha, the official scribe of Pedro Alvares Cabral, the commander of the discovery fleet which landed in the present state of Bahia, wrote a letter to the King of Portugal describing in glowing terms the beauty of the land. In fact however, the portuguese colonizers had many armed conflicts with the indigenous peoples.

Slavery and the Bandeiras

The mutual feeling of wonderment and good relationship was to end in the succeeding years. The Portuguese colonists, all males, started to have children with female natives, creating a new generation of mixed-race people who spoke Indian languages (in the city of São Paulo in the first years after her foundation, a Tupi language called Nheengatu). The children of these Portuguese men and Indian women formed the majority of the population. Groups of fierce conquistadores' sons organized expeditions called "bandeiras" (flags) into the backlands to claim the land to the Portuguese crown and to look for gold and precious stones.[18]

The indigenous people were soon infected by diseases brought by the Europeans against which they had no natural immunity, and began dying in enormous numbers. The waning indigenous population could not provide sufficient labor for the intensive European agriculture of Cane and other crops so the Portuguese had to start importing black slaves from Africa.

The Jesuits

The Jesuit priests, who had come with the first Governor General to provide for religious assistance to the colonists, but mainly to convert the "pagan" peoples to Catholicism, took the side of the natives and extracted a Papal bull stating that they were human and should be protected.

Jesuit priests such as fathers José de Anchieta and Manoel da Nóbrega studied and recorded their language and founded mixed settlements, such as São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga, where colonists and natives lived side by side, speaking the same Língua Geral (common language) and freely interbred. They began also to establish more remote villages peopled only by civilized natives, called Missiones, or reductions (see the article on the Guarani people for more details).

Indian wars

A number of wars between several tribes, such as the Tamoio Confederation, and the Portuguese ensued, sometimes with the natives siding with enemies of Portugal, such as the French, in the famous episode of France Antarctique in Rio de Janeiro, sometimes allying themselves to Portugal in their fight against other tribes. At approximately the same period, a German soldier, Hans Staden, was captured by the Tupinamba and released after a while. He described it in a famous book.

Government protection

In the 20th century, the Brazilian Government adopted a more humanitarian attitude and offered official protection to the indigenous people, including the establishment of the first Indian reserves. The National Indian Service (today the FUNAI, or Fundação Nacional do Índio) was established by Cândido Rondon, a Bororo Indian himself and a military officer of the Brazilian Army. The remaining unacculturated tribes have been contacted by FUNAI, and accommodated within Brazilian society in varying degrees. However, the exploration of rubber and other Amazonic natural resources led to a new cycle of invasion, expulsion, massacres and death, which continues to this day.

Canada

The most commonly preferred term for the indigenous peoples of what is now Canada is Aboriginal peoples. Of these Aboriginal peoples who are not Inuit or Métis, "First Nations" is the most commonly preferred term of self-identification. First Nations peoples make up approximately 3 percent of the Canadian population; Inuit, Métis and First Nations together make up 5 percent. The official term for First Nations people—that is, the term used by both the Indian Act, which regulates benefits received by members of First Nations, and the Indian Register, which defines who is a member of a First Nation—is Indian.

Chile

Less than 5 percent of Chileans belong to indigenous peoples, such as the Mapuche in the country's central valley and lake district, and the Mapuche successfully fought off defeat in the first 300-350 years of Spanish during the War of Arauco. Relation with the new Chilean Republic were good until the Chilean state decided to occupy their lands. During the Occupation of Araucanía the Mapuche surrendered to the country's army in the 1880s. The former land was opened to settlement for mestizo and white Chileans. Conflict over Mapuche land rights continued until present days.

Colombia

A small minority today within Colombia's overwhelmingly Mestizo and Afro-Colombian population, Colombia's indigenous peoples nonetheless encompass at least 85 distinct cultures and more than 1,378,884 people[19]. A variety of collective rights for indigenous peoples are recognized in the 1991 Constitution.

One of these is the Muisca culture, a subset of the larger Chibcha ethnic group, famous for their use of gold, which led to the legend of El Dorado. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Chibchas were the largest native civilization between the Incas and the Aztecs.

Ecuador

Ecuador was the site of many indigenous cultures, and civilizations of different proportions. An early sedentary culture, known as the Valdivia culture, developed in the coastal region, while the Caras and the Quitus unified to form an elaborate civilization that ended at the birth of the Capital Quito. The Cañaris near Cuenca were the most advanced, and most feared by the Inca, due to their fierce resistance to the Incan expansion. Their architecture remains were later destroyed by Spaniards and the Incas. Many Ameridian natives still exist today living in isolation with little contact to the outerworld. Most natives remained unmixed in the fusion that occurred after colonization because they inhabited such remote areas like the jungle, and the Andes. Many of the Cañaris, and other natives still occupy their descendents original locations.

Guatemala

Many of the indigenous peoples of Guatemala are of Maya heritage. Other groups are Xinca people and Garífuna.

Pure Maya account for some 40 percent of the population; although around 40 percent of the population speaks an indigenous language, those tongues (of which there are more than 20) enjoy no official status.

Mexico

The territory of modern-day Mexico was home to numerous indigenous civilizations prior to the arrival of the European conquistadores: The Olmecs, who flourished from between 1200 B.C.E. to about 400 B.C.E. in the coastal regions of the Gulf of Mexico; the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs, who held sway in the mountains of Oaxaca and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; the Maya in the Yucatán (and into neighbouring areas of contemporary Central America); the Purepecha or Tarascan in present day Michoacán and surrounding areas, and the Aztecs, who, from their central capital at Tenochtitlan, dominated much of the centre and south of the country (and the non-Aztec inhabitants of those areas) when Hernán Cortés first landed at Veracruz.

In contrast to what was the general rule in the rest of North America, the history of the colony of New Spain was one of racial intermingling (mestizaje). Mestizos quickly came to account for a majority of the colony's population; however, significant pockets of pure-blood indígenas (as the native peoples are now known) have survived to the present day.

With mestizos numbering some 60 percent of the modern population, estimates for the numbers of unmixed indigenous peoples vary from a very modest 10 percent to a more liberal 30 percent of the population. The reason for this discrepancy may be the Mexican government's policy of using linguistic, rather than racial, criteria as the basis of classification.

In the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca and in the interior of the Yucatán peninsula the majority of the population is indigenous. Large indigenous minorities, including Nahuas, Purépechas, and Mixtecs are also present in the central regions of Mexico. In Northern Mexico indigenous people are a small minority: they are practically absent from the northeast but, in the northwest and central borderlands, include the Tarahumara of Chihuahua and the Yaquis and Seri of Sonora. Many of the tribes from this region are also recognized Native American tribes from the U.S. Southwest such as the Yaqui and Kickapoo.

While Mexicans are universally proud of their indigenous heritage, modern-day indigenous Mexicans are still the target of discrimination and outright racism[citation needed]. In particular, in areas such as Chiapas — most famously, but also in Oaxaca, Puebla, Guerrero, and other remote mountainous parts — indigenous communities have been left on the margins of national development for the past 500 years. Indigenous customs and uses enjoy no official status. The Huichols of the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Zacatecas, and Durango are impeded by police forces in their ritual pilgrimages, and their religious observances are interfered with[citation needed].

Nicaragua

The Miskito are Native American people in Central America. Their territory expands from Cape Cameron, Honduras, to Rio Grande, Nicaragua along the Miskito Coast. There is a native Miskito language, but large groups speak Miskito creole English, Spanish, Rama and others. The creole English came about through frequent contact with the British. Many are Christians.

Over the centuries the Miskito have intermarried with escaped slaves who have sought refuge in Miskito communities. Traditional Miskito society was highly structured, with a defined political structure. There was a king but he did not have total power. Instead, the power was split between him, a governor, a general, and by the 1750s, an admiral. Historical information on kings is often obscured by the fact that many of the kings were semi-mythical.

Peru

Most Peruvians are either indigenous or mestizos (of mixed Indigenous, African, European and Asian ancestry). Peru has the largest indigenous population of South America, and its traditions and customs have shaped the way Peruvians live and see themselves today. Cultural citizenship—or what Renato Rosaldo has called, "the right to be different and to belong, in a democratic, participatory sense" (1996:243)—is not yet very well developed in Peru. This is perhaps no more apparent than in the country's Amazonian regions where indigenous societies continue to struggle against state-sponsored economic abuses, cultural discrimination, and pervasive violence.

Throughout the Peruvian Amazon, indigenous peoples have long faced centuries of missionization, unregulated streams of colonists, land-grabbing, decades of formal schooling in an alien tongue, pressures to conform to a foreign national culture, and more recently, explosive expressions of violent social conflict fueled by a booming underground coca economy. The disruptions accompanying the establishment of extractive economies, coupled with the Peruvian state-sanctioned civilizing project, have led to a devastating impoverishment of Amazonia's richly variegated social and ecological communities.[20]

The most visited tourist destinations of Peru were built by indigenous peoples (the Quechua, Aymara, Moche, etc.), while Amazonian peoples, such as the Urarina, Bora, Matsés, Ticuna, Yagua, Shipibo and the Aguaruna, developed elaborate shamanic systems of belief prior to the European Conquest of the New World. Macchu Picchu is considered one of the marvels of humanity, and it was constructed by the Inca civilization. Even though Peru officially declares its multi-ethnic character and recognizes at least six–dozen languages —including Quechua, Aymara and hegemonic Spanish— discrimination and language endangerment continue to challenge the indigenous peoples in Peru.[21]

United States

Indigenous peoples in what is now the United States are commonly called "American Indians" but more recently have been referred to as "Native Americans." Native Americans make up 2 percent of the population, with more than 6 million people identifying themselves as such, although only 1.8 million are registered tribal members. A minority of U.S. Native Americans live on Indian reservations. There are also many Southwestern U.S. tribes, such as the Yaqui and Apache, that have registered tribal communities in Northern Mexico and several bands of Blackfoot reside in southern Alberta. There is further Native American ancestry by various extraction existing across all social races that is mostly unaccounted for.

Other parts of the Americas

Indigenous peoples make up the majority of the population in Bolivia and Peru, and are a significant element in most other former Spanish colonies. Exceptions to this include Costa Rica, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Argentina, Dominican Republic, and Uruguay. At least three of the Amerindian languages (Quechua in Peru and Bolivia, Aymara also in Bolivia, and Guarani in Paraguay) are recognized along with Spanish as national languages. And the controversial issue on the significance of indigenous peoples and their culture has on Chile, the South American country was treated more like an European-derived one by the fact European immigration was dense, but smaller than immigration to Uruguay and neighboring Argentina, but a majority of Chileans are mestizos of varied degrees of mixed European and American Indian ancestry.

Notes

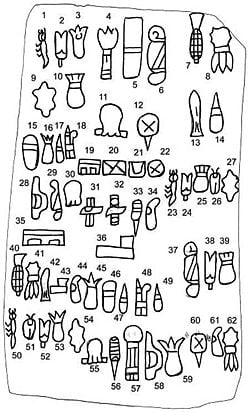

- ↑ Skidmore (2006, pp.1-4). The numbers appearing next to each glyph are identifiers used by archaeologists investigating the find.

- ↑ See Jacobs 2001 for an extensive review of the evidence for migration timings, and Jacobs 2002 for a survey of migration models.

- ↑ Jacobs (2002).

- ↑ Mann (2005).

- ↑ "DNA Ties Together Scattered Peoples," Los Angeles Times (accessed September 11 2006); reprint

- ↑ See also Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas.

- ↑ See Thornton's (2006) review of 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (Mann 2005).

- ↑ Taylor (2001, p.40).

- ↑ See Varese (2004), as reviewed in Dean (2006).

- ↑ Ancient Horse (Equus cf. E. complicatus), The Academy of Natural Sciences, Thomas Jefferson Fossil Collection, Philadelphia, PA, http://www.ansp.org/museum/jefferson/otherFossils/equus.php

- ↑ See also population history of American indigenous peoples.

- ↑ As characterized by Mann (2005)

- ↑ Native Americans of North America, http://encarta.msn.com/text_761570777___2/Native_Americans_of_North_America.html, Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006, Trudy Griffin-Pierce, accessed September 14, 2006

- ↑ http://www.allbusiness.com/agriculture-forestry-fishing-hunting/331083-1.html

- ↑ Los pueblos indígenas de México

- ↑ INDEC: Encuesta Complementaria de Pueblos Indígenas (ECPI) 2004 - 2005

- ↑ Rodrigues 1985

- ↑ São Paulo

- ↑ DANE 2005 national census

- ↑ See for example Dean and Levi (2003)

- ↑ A view expressed by Dean (2003)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Churchill, Ward (1997). A Little Matter of Genocide. City Lights Books. ISBN 0-872-86323-9.

- Dean, Bartholomew (2003). "State Power and Indigenous Peoples in Peruvian Amazonia: A Lost Decade, 1990-2000", in David Maybury-Lewis (Ed.): The Politics of Ethnicity Indigenous Peoples in Latin American States, David Rockefeller Center Series on Latin American Studies. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, pp.199–238. ISBN 0-674-00964-9.

- Dean, Bartholomew (January 2006). Salt of the Mountain: Campa Asháninka History and Resistance in the Peruvian Jungle (review). The Americas 62 (3): pp.464–466.

- Dean, Bartholomew and and Jerome M. Levi, (Eds.) (2003). At the Risk of Being Heard; Identity, Indigenous Rights, and Postcolonial States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-09736-9.

- Jacobs, James Q. (2001). The Paleoamericans: Issues and Evidence Relating to the Peopling of the New World. Anthropology and Archaeology Pages. jqjacobs.net. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- Jacobs, James Q. (2002). Paleoamerican Origins: A Review of Hypotheses and Evidence Relating to the Origins of the First Americans. Anthropology and Archaeology Pages. jqjacobs.net. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- Jones, Peter N. (2005). Respect for the Ancestors: American Indian Cultural Affiliation in the American West. Boulder CO: Bauu Press. ISBN 0-972-13492-1.

- Kane, Katie (1999). Nits Make Lice: Drogheda, Sand Creek, and the Poetics of Colonial Extermination. Cultural Critique 42: pp.81–103.

- Krech, Shepard III (1999). The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-04755-5.

- Mann, Charles C. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Knopf Publishing Group. ISBN 1-400-04006-X.

- Skidmore, Joel (2006). The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing (PDF). Mesoweb Reports & News. Mesoweb. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- Taylor, Alan (2001). American colonies. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-87282-2.

- Thornton, Bruce S. (July 2006). New World, Old Myths: A review of Charles C. Mann's 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Claremont Review of Books. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- Varese, Stefano (2004). Salt of the Mountain: Campa Asháninka History and Resistance in the Peruvian Jungle, Susan Giersbach Rascón (trans.), Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-806-13512-3.

External links

- http://www.garviespointmuseum.com/indian-archaeology-long-island.php Native American Archaeology of Long Island, NY

- http://www.reacheverychild.com/feature/native.html Educational sites for teachers

- Indigenous Women of the Americas

- Chakana: NGO & knowledge centre about Indians of the highlands

- Speaking4Earth: action site about indigenous issues

- Dutch Centre for Indigenous Peoples

- Photos and videos of Bolivian, Mexican, Peruvian and Guatemaltec indigenous people

- Tlingit National Anthem, Alaska Natives and Native American resources

- A History of Aboriginal Treaties and Relations in Canada This site includes contextual materials, links to digitized primary sources and summaries of primary source documents.

- Uncontacted Indian Tribe Found in Brazilian Amazon

- Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (Instituto Socioambiental)

- Etnolinguistica.Org: discussion list on South American languages

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International

- Indigenous peoples in Brazil at Google Video

- Google Video on Indigenous People of Brazil

- "Tribes" of Brazil

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.