Patagonia

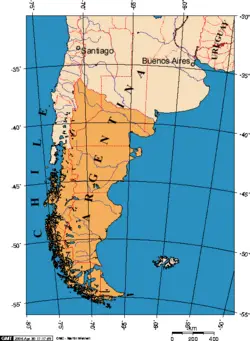

Patagonia is the portion of South America which to the east of the Andes Mountains, lies south of the NeuquĂ©n and RĂo Colorado rivers, and, to the west of the Andes, south of (42° S). The Chilean portion embraces the southern part of the region of Los Lagos, and the regions of Aysen and Magallanes (excluding the portion of Antarctica claimed by Chile). East of the Andes the Argentine portion of Patagonia includes the provinces of NeuquĂ©n, RĂo Negro, Chubut, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego, as well as the southern tip of Buenos Aires province. It covers an area of 757,000 square kilometers.

Patagonia has around 1,740,000 (2001 census) inhabitants. Seventy percent of its population is located in just 20 percent of its territory.

Patagonia has become renowned as one of the few surviving regions of the world designated as an "eden" or region where pristine nature still exists. Known for its arid plains, breathtaking mountain vistas, and bountiful, diverse wildlife, Patagonia is an exciting lure for eco-tourists and outdoor sports enthusiasts.

History

First human settlement

Human habitation of the region dates back thousands of years, with some early archaeological findings in the southern part of the area dated to the tenth millennium B.C.E., although later dates of around the eighth millennium B.C.E. are more widely recognized. The region appears to have been inhabited continuously since that time by various cultures and alternating waves of migration, but the details of these inhabitants have not yet been thoroughly researched. Several sites have been excavated, notably caves in Ăltima Esperanza in southern Patagonia, and Tres Arroyos on Tierra del Fuego, that support this date.

Around 1000 B.C.E., Mapuche-speaking agriculturalists penetrated the western Andes and from there across into the eastern plains and down to the far south. Through confrontation and technological ability, they came to dominate the other peoples of the region in a short space of time, and are the principal indigenous community today.

The indigenous peoples of the region include the Tehuelches, whose numbers and society were reduced to near extinction not long after the first contacts with Europeans. âConquest of the Desertâ was the name of the campaign waged by the Argentinian government in the 1870s for the purpose of taking control of Patagonia away from the indigenous tribes.

Early European accounts: Sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

The region of Patagonia was first noted in 1520 in European accounts of the expedition of Ferdinand Magellan, who on his passage along the coast named many of the more striking featuresâGulf of San Matias, Cape of 11,000 Virgins (now simply Cape Virgenes), and others. However, it is also possible that earlier navigators like Amerigo Vespucci reached the area (his own account of 1502 has it that he reached its latitudes), however his failure to accurately describe the main geographical features of the region such as the Rio de la Plata casts some doubt on his claims.

Rodrigo de Isla, dispatched inland in 1535 from San Matias by Alcazava Sotomayor (on whom western Patagonia had been conferred by the king of Spain), was the first European to traverse the great Patagonian plain. However, because of the mutiny of his men, he did not cross the Andes to reach the Chilean side.

Pedro de Mendoza, on whom the country was next bestowed, lived to found Buenos Aires, but not to carry on explorations to the south. Alonzo de Camargo (1539), Juan Ladrilleros (1557) and Hurtado de Mendoza (1558) helped make known the western coasts, and Sir Francis Drake's voyage in 1577âdown the eastern coast through the strait and northward by Chile and Peruâbrought more interest in the region but the geography of Patagonia owes more to Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa (1579-1580), who, devoting himself especially to the southwest region, made careful and accurate surveys. He founded settlements at Nombre de Dios and San Felipe.

Dutch adventurers later blazed Magellan's trail and in 1616, a Dutch navigator named the southernmost tip of Argentinaâs Cape Horn after his hometown, Hoorn.

Patagonian giants: Early European perceptions

According to Antonio Pigafetta, one of the Magellan expedition's few survivors and its published chronicler, Magellan bestowed the name "PatagĂŁo" (or Patagoni) on the inhabitants they encountered there, and the name "Patagonia" for the region. Although Pigafetta's account does not describe how this name came about, subsequent popular interpretations gave credence to a derivation meaning âland of the big feet.â However, this etymology is questionable.

Pigafetta's accounts were best known for his reports of meetings with the local inhabitants, who he claimed measured some nine to twelve feet in heightâ"...so tall that we reached only to his waist"âhence the later idea that Patagonia meant "big feet." This supposed race of Patagonian giants or "Patagones" became the main European perception of this little-known and distant area. Early charts of the New World sometimes added the legend regio gigantum ("region of the giants") to the Patagonian area. By 1611 the Patagonian god Setebos (Settaboth in Pigafetta) became even more familiar through William Shakespeare's two references in The Tempest.

This concept of giant natives persisted for some 250 years and was sensationally re-ignited in 1767 when an "official" (but anonymous) account was published of Commodore John Byron's voyage of global circumnavigation in the HMS Dolphin. Byron and his crew had spent some time along the coast, and the publication Voyage Round the World in His Majestyâs Ship the Dolphin, seemed to give proof positive of their existence; the publication became an overnight best-seller, thousands of extra copies were sold and other prior accounts of the region were hastily re-published (even those in which giant-like natives were not mentioned at all).

However, the Patagonian giant frenzy was to die down substantially a few years later when some more sober and analytical accounts were published. In 1773 John Hawkesworth published on behalf of the Admiralty a compendium of noted English southern-hemisphere explorers' journals, including that of James Cook and Byron. In this publication, drawn from their official logs, it became clear that the people Byron's expedition had encountered were no taller than 6 feet, 6 inchesâtall, perhaps, but by no means giants. Interest soon subsided, although awareness of and belief in the myth persisted in some quarters even up into the twentieth century.

Expansion and exploration: Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

In the second half of the eighteenth-century knowledge of Patagonia was further augmented by the voyages of Byron (1764-1765), Samuel Wallis (1766, in the same HMS Dolphin which Byron had earlier sailed in) and Louis Antoine de Bougainville (1766). Thomas Falkner, a Jesuit who resided nearly 40 years in the area, published his Description of Patagonia in 1774.

The expeditions of the HMS Adventure (1826-1830) and the HMS Beagle (1832-1836) under Philip Parker King and Robert FitzRoy, respectively, were originated with the goal of completing the surveys of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego begun under King (1826-1830). The voyage of Beagle would later gain notoriety because of passenger Charles Darwin.

In 1869 Captain George Chaworth Musters wandered through the whole length of the country from the strait to the Manzaneros in the north-west with a band of Tehuelches and collected a great deal of information about the people and their mode of life.

European Immigrations

Patagonia is populated primarily by people of European descent. European settlements didn't take hold and develop until late in the 1800's. Until then there were only sparse populations of indigenous peoples and a small number of Welsh colonists.

The first Welsh settlers arrived on July 27, 1865, when 153 people arrived aboard the converted merchant ship Mimosa. The settlers traveled overland until they reached the valley of the Chubut River where they had been promised one hundred square miles for settlement by the government of Argentina. The town that developed there is present-day Rawson, the capital of Chabut province. The Welsh settlers made contact with the indigenous Tehuelche people within months of their arrival. Similar to the experience of the pilgrims who arrived in North America at Plymouth, the local native people helped the settlers survive food shortages in their new home. There were a few other waves of Welsh migration throughout the following decades; however, the Welsh soon became outnumbered by Spanish Basques, Italians, German, French and Russian immigrants who also took up farming and ranching throughout the river valleys of Patagonia.

Culture and Religion

The official language of Argentina is Spanish. Immigrant settlements and tourism has introduced international flavor to this region and Welsh, Italian, French and English speakers can be also be found. Small communities of indigenous peoples speak Mapuche, Guarani and a few other native languages.

Roman Catholicism is the dominant religious faith of the region, established by Jesuit missionaries in the eighteenth century. There is freedom of religious practice in Patagonia and other religious faiths found there include Protestant denominations, Judaism, Islam, Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox, as well as indigenous religions.

Generally the cuisine found in Patagonia is influenced by the cuisine of Argentina. There are some regional specialties influenced by the Welsh settlers such as scones served with clotted cream in teahouses and Italian pastas served with roasted beef, venison or lamb. The special drink for which this region is known is called mate, an energizing herbal tea concoction of yerba mate leaves. It is specially prepared for one person at a time, drunk out of a gourd, and sipped through a silver straw. Drinking mate with friends and family is a social activity.

There are numerous art, cultural, folkloric, and agricultural festivities and exhibitions throughout the year that celebrate the Patagonian lifestyle that can be found throughout the cities and towns of this region.

Physiography

The Argentine portion of Patagonia is mostly a region of vast steppe-like plains, rising in a succession of abrupt terraces about 100 meters (330 feet) at a time, and covered with an enormous bed of shingle almost bare of vegetation. In the hollows of the plains are ponds or lakes of brackish and fresh water. Towards the Andes the shingle gives way to porphyry, granite, and basalt lavas, while animal life becomes more abundant and vegetation more luxuriant, acquiring the characteristics of the flora of the western coast, and consisting principally of southern beech and conifers.

Geology

Patagonia is geographically and climatically diverse. As well as the classic dry southern plains of Argentina, the region includes the Andean highlands and lake districts, the moist Pacific coast and the rocky and frigid Tierra del Fuego. The diverse terrain is all shaped in one way or another by the Andean Cordillera, the longest continuous mountain chain on earth. The Andes are formed by the Pacific Ocean Nazca Plate pushing under the South American plate. This seismic activity is accompanied by volcanic activity. Patagonia still has many active volcanoes. There are still petrified forests, formed by volcanic ash burying large tracts of land.

Glaciers occupy the valleys of the Cordillera and some of its lateral ridges and descend to lakes like San MartĂn Lake, Viedma Lake, and Argentino Lake leaving in their wake many icebergs. The fjords of the Cordillera, occupied by deep lakes on the east, and on the west by the Pacific channels, are as much as 250 fathoms (460 meters) in depth, and soundings taken in them show that the fjords are deeper in the vicinity of the mountains than to the west of the islands.

Provinces and Economy

There are five provinces on the Argentinian side of Patagonia. They are Neuquen, Rio Negro, Chubut, Santa Cruz and Tiero del Fuego. Patagonia also touches on the Chilean regions of Los Lagos, Aysen, and Magallines. The borders of the areas in Patagonia between Chile and Argentina have sometimes been in dispute. The Chilean Patagonia is considered very remote and, like the Argentinian side, is sparsely populated with people but abounds with many unique species of animals.

Agriculture, ranching and tourism are the main economic activities in the Argentinean side of Patagonia. There is an abundance of natural resources such as timber, mighty rivers, and deposits of gold, silver, copper and lignite still mostly undeveloped. A series of dams on the Limay and Neuquen rivers produce hydro power in Neuquen province. Irrigated areas of the Negro and Colorado River valleys make it favorable for ranching and farming. The province of Chabut produces the high quality wheat of the Argentine Republic. Oil and natural gas production center on the area around Comodoro Rivadavia.

Neuquén

Neuquén covers 94,078 square kilometers (36,324 square miles), including the triangle between the rivers Limay River and Neuquén River, and extends southward to the northern shore of Lake Nahuel-Huapi (41° S) and northward to the Rio Colorado.

RĂo Negro

RĂo Negro covers 203,013 square kilometers (78,383 square miles), extending from the Atlantic to the Cordillera of the Andes, to the north of 42° S.

Chubut

Chubut covers 224,686 square kilometers (86,751 square miles), embracing the region between 42° and 46° S.

Santa Cruz

Santa Cruz, which stretches from the 46° to the 50° S parallelâas far south as the dividing line with Chile, and between Point Dungeness and the watershed of the Cordilleraâhas an area of 243,943 square kilometers (94,186 square miles).

The territory of Santa Cruz is arid along the Atlantic coast and in the central portion between 46° and 50° S. Puerto Deseado is the outlet for the produce of the Andean region situated between lakes Buenos Aires and Pueyrredon.

Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego is an archipelago at the southernmost tip of Patagonia, divided between Argentina and Chile. It consists of the 47,992 square kilometers of the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, and several minor islands.

Climate

The climate is less severe than was supposed by early travelers. The east slope is warmer than the west, especially in summer, as a branch of the southern equatorial current reaches its shores, whereas the west coast is washed by a cold current. At Puerto Montt, on the inlet behind ChiloĂ© Island, the mean annual temperature is 11 °C (52 °F) and the average extremes 25.5 °C (78 °F) and â1.5 °C (29.5 °F), whereas at Bahia Blanca near the Atlantic coast and just outside the northern confines of Patagonia the annual temperature is 15 °C (59 °F) and the range much greater. At Punta Arenas, in the extreme south, the mean temperature is 6 °C (43 °F) and the average extremes 24.5 °C (76 °F) and â2 °C (28 °F). The prevailing winds are westerly, and the westward slope has a much heavier precipitation than the eastern; thus at Puerto Montt the mean annual precipitation is 2.46 meters (97 inches), but at Bahia Blanca it is 480 millimeters (19 inches). At Punta Arenas it is 560 millimeters (22 inches).

Fauna

The guanaco, the puma, the zorro or Brazilian fox (Canis azarae), the zorrino or Mephitis patagonica (a kind of skunk), and the tuco-tuco or Ctenomys niagellanicus (a rodent) are the most characteristic mammals of the Patagonian plains. The guanaco roam in herds over the country and form with the rhea (Rhea americana, and more rarely Rhea darwinii) the chief means of subsistence for the natives, who hunt them on horseback with dogs and bolas.

Bird life is often wonderfully abundant. The carancho or carrion-hawk (Polyborus tharus) is one of the characteristic sights of the Patagonian landscape; the presence of long-tailed green parakeets (Conurus cyanolysius) as far south as the shores of the strait attracted the attention of the earlier navigators; and hummingbirds may be seen flying amidst the falling snow. Water-fowl is abundant and includes the flamingo, the upland goose, and in the strait the steamer duck.

Environmental Concerns

There are ten national parks in the Patagonia region on the Argentinian side and three national monuments, all of which are protected areas for particular flora and fauna. As early as 1934 the first national park, Naheul Huapi, was developed.

Although Patagonia is richly endowed with natural resources, as with other complex ecosystems throughout the world, natural resources can become exploited to depletion or mismanaged. Many of its terrestrial species, including the guanaco, rhea, upland goose, and mara, are facing the consequences of uncontrolled hunting. Also, many of the unique native animals are considered pests by local landowners and in some cases a source of cheap food by local inhabitants so their populations are dwindling.

Another environmental concern is the oily ballast tankers dump at sea as they move back and forth between the oil fields in southern Patagonia and the busy ports of Buenos Aires and Bahia Blanca. Each year between 1985 and 1991, an estimated 41,000 Magellanic penguins died from oil poisoning.

Since Patagonia's natural beauty has become world renowned, more attention has come to this region from the world's scientific and conservationist communities. Organizations such as the United Nations-affiliated organization Global Environment Facility (GEF) have partnered with the Patagonian non-profit Foundation Patagonia Natural and created a coastal management plan that is positively impacting coastal fisheries, ranching and farming, and conservation of land and marine animal species.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

All links retrieved June 25, 2007.

- Aagesen, D. Crisis and Conservation at the End of the World: Sheep Ranching in Argentine Patagonia. May 2002. Dept. of Geography, State University of New York. Cambridge Journals, Cambridge University Press.

- Beasley, Conger and Tim Hauf (photographer). Patagonia: Wild Land at the End of the Earth. Tim Hauf Photography, 2004. ISBN 0972074333

- Beccaceci, Marcelo D. Natural Patagonia / Patagonia natural: Argentina & Chile Pangaea (Bilingual edition). St. Paul, MN: Pangaea Publishing, 1998. ISBN 0963018035

- Chatwin, Bruce. In Patagonia. New York: Penguin Classics, 1977. ISBN 0142437190

- The Columbia Gazetteer of the World Online. âArgentina Demographics and Geography.â New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Global Environmental Facility. âPromoting Sustainable Land Management.â Washington, DC: Global Environmental Facility, 2006.

- Imhoff, Dan and Roberto Cara. Farming with the Wild: Enhancing Biodiversity on Farms and Ranches. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003. ISBN 1578050928

- InterPatagonia.com. âAgenda in Patagonia: The Most Important Festivals and Events in Patagonia.â

- Lutz, Richard L. Patagonia: At the Bottom of the World. Salem, OR: DIMI Press, 2002. ISBN 0931625386

- McEwan, Colin; Luis Alberto Borrero and Alfredo Prieto (eds.). Patagonia: Natural History, Prehistory, and Ethnography at the Uttermost End of the Earth. Trustees of the British National Museum. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998. ISBN 0691058490

External Links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- Reader's Digest World Presents The Living Edens â PBS Online.

- Patagonia travel guide by Inter Patagonia â InterPatagonia.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.