Cassava

| Cassava | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Manihot esculenta Crantz |

Cassava is a tuberous, woody, shruby perennial plant, Manihot esculenta, of the Euphorbiaceae (spurge family), characterized by palmately lobed leaves, inconspicuous flowers, and a large, starchy, tuberous root with a tough, papery brown bark and white to yellow flesh. The name cassava also is used for this tuber, which is a major source of carbohydrates and is a dietary staple in many tropical nations. This plant and root also are known as yuca, manioc, and mandioca.

While native to South America, cassava now is extensively cultivated as an annual crop in many tropical and subtropical regions of the world, including Africa, India, and Indonesia, with Africa its largest center of production. This is a prolific crop that can grow in poor soil and is drought tolerant. It is the one of the most important food plants in the tropics and the third largest source of carbohydrates for human food in the world.

The roots and leaves contain cyanogenic glucosides, which offer a protection against some herbivores, but also make the plant toxic to humans if consumed without prior treatment, such as leaching and drying. In particular, the varieties known as "bitter cassava" contain significant amounts of cyanide, with the "sweet cassava" less toxic. It is a unique aspect of human beings to be able to process toxic plants into a form that makes them edible.

Cassava is the source of flour called tapioca, as well as is used for breads, and alcoholic beverages. The leaves also can be treated and eaten. However, cassava is a poor source of protein and reliance on cassava as a staple food is associated with the disease kwashiorkor.

Description

Manihot esculenta, or cassava, is a slightly woody, generally shruby plant that typically grows from one to three meters (3-10 feet) in height (Katz and Weaver 2003). The leaves are nearly palmate (fan- or hand-shaped) and dark green in color. There are over 5,000 varieties of cassava known, each with distinct qualities, and they range from low herbs to shrubs with many branches, to unbranched trees.

The cassava root is long and tapered, with a firm homogeneous flesh encased in a detachable rind, about 1 millimeter thick, and rough and brown on the outside, just like a potato. Commercial varieties can be 5 to 10 centimeters in diameter at the top, and 50 to 80 centimeters long. A woody cordon runs along the root's axis. The flesh can be chalk-white or yellowish.

Although there are many varieties of cassava, there are two main varieties, sweet and bitter. These are classified on the basis of how toxic are the levels of cyanogenic glucosides. (See toxicity and processing.)

The cassava plant gives the highest yield of food energy per cultivated area per day among crop plants, except possibly for sugarcane.

Cultivation and production

Cassava is a very hardy plant. It tolerates drought better than most other crops, and can grow well in very poor, acidic soils through its symbiotic relationship with soil fungi (mycorrhizae) (Katz and Weaver 2003). Cassava is a prolific crop, which can yield up to 13 million kcal/acre (Bender and Bender 2005).

Cassava typically is grown by small-scale farmers using traditional methods, and often on land not suitable for other crops (Katz and Weaver 2003). Cassava is propagated by cutting a mature stem into sections of approximately 15 centimeters and planting these prior to the wet season. These plantings require adequate moisture during the first two to three months, but subsequently are drought resistant (Katz and Weaver 2003). The roots are harvestable after six to twelve months and can be harvested any time in the following two years, providing farmers with a remarkable amount of flexibility (Katz and Weaver 2003).

Cassava is harvested by hand by raising the lower part of stem and pulling the roots out of the ground, then removing them from the base of the plant. The upper parts of the stems with the leaves are plucked off before harvest.

Roots using deteriorate within three to four days after harvesting and thus are either consumed immediately or processed into a form with better storage qualities (Katz and Weaver 2003).

World production of cassava root was estimated to be 184 million metric tons in 2002. The majority of production is in Africa, where 99.1 million metric tons were grown, while 51.5 million metric tons were grown in Asia, and 33.2 million metric tons in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, based on the statistics from the FAO of the United Nations, Thailand is the largest exporting country of Dried Cassava with a total of 77 percent of world export in 2005. The second largest exporting country is Vietnam, with 13.6 percent, followed by Indonesia (5.8 percent) and Costa Rica (2.1 percent).

Toxicity and processing

Cassava is remarkable and infamous as a food crop because it actually can be toxic to consume. The leaves and roots contain free and bound cyanogenic glucosides. These are converted to cyanide in the presence of linamarase, a naturally occurring enzyme in cassava. Hydrogen cyanide is a potent toxin. Cyanogenic glucosides can be found throughout the plant and in all varieties of cassava (Katz and Weaver 2003).

Cassava leaves, although high in protein, cannot be consumed raw because of the cyanogenic glucosides. However, the leaves often are consumed after cooking to remove the prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide).

The roots are a very popular food, however. The process for making them edible depends on the variety. Cassava varieties are often categorized as either "sweet" or "bitter," signifying the absence or presence of toxic levels of cyanogenic glucosides. The so-called "sweet" (actually "not bitter") cultivars can produce as little as 20 milligrams of cyanide (CN) per kilogram of fresh roots, while "bitter" ones may produce more than 50 times as much (1 g/kg). Cassavas grown during drought are especially high in these toxins (Aregheore and Agunbiade 1991; White et al. 1998). One dose of pure cassava cyanogenic glucoside (40mg) is sufficient to kill a cow.

Varieties known as sweet, or low-cyanide cassava may be consumed after being peeled and cooked. However, those referred to as bitter, or high-cyanide cassava require more extensive processing before they are safe to consume. These techniques (fermenting, grating, sun drying) serve to damage the plant tissues and allow the liberation of the hydrogen cyanide (Katz and Weaver 2003).

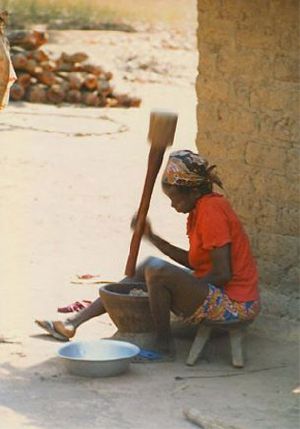

Large-rooted bitter varieties used for production of flour or starch may be peeled and then ground into flour, which is then soaked in water, squeezed dry several times, and toasted. The starch grains that float to the surface during the soaking process are also used in cooking (Padmaja 1995). The flour is used throughout the Caribbean. The traditional method used in West Africa is to peel the roots and put them into water for three days to ferment. The roots then are dried or cooked. In Nigeria and several other West African countries, including Ghana, Benin, Togo, Cote d'Ivoire, and Burkina Faso, they are usually grated and lightly fried in palm oil to preserve them. The result is a foodstuff called 'Gari'. Fermentation is also used in other places such as Indonesia.

South American Amerindians relied on cassava and generally understand that processing methods were necessary to avoid getting sick. There is no evidence of chronic or acute cyanide toxicity among Amerindians (Katz and Weaver 2003). However, problems still do occur in various parts of the world due to inadequate processing, such as due to a rush to market or famine (Katz and Weaver 2003).

Konzo (also called mantakassa) is a paralytic neurological disease associated with several weeks of almost exclusive consumption of insufficiently processed bitter cassava. Dr Jasson Ospina, an Australian plant chemist, has developed a simple method to reduce the cyanide content of cassava flour (Bradbury 2006). The method involves mixing the flour with water into a thick paste and then letting it stand in the shade for five hours in a thin layer spread over a basket, allowing an enzyme in the flour to break down the cyanide compound. The cyanide compound produces hydrogen cyanide gas, which escapes into the atmosphere, reducing the amount of poison by up to five-sixths and making the flour safe for consumption the same evening. This method is currently being promoted in rural African communities that are dependent on cassava (ANU 2007).

The reliance on cassava as a food source and the resulting exposure to the goitrogenic effects of thiocyanate has been responsible for the endemic goitres seen in the Akoko area of southwestern Nigeria (Akindahunsi et al. 1998).

History

Wild populations of M. esculenta subsp. flabellifolia, considered to be the progenitor of domesticated cassava, are centered in west-central Brazil where it was likely first domesticated no more than 10,000 years BP (Olsen et al. 1999). By 6600 B.C.E., manioc pollen appears in the Gulf of Mexico lowlands, at the San Andres archaeological site (Pope et al. 2001). The oldest direct evidence of cassava cultivation comes from a 1,400 year old Maya site, Joya de Ceren, in El Salvador (UCB 2007) although the species Manihot esculenta likely originated further south in Brazil and Paraguay.

With its high food potential, cassava had become a staple food of the native populations of northern South America, southern Mesoamerica, and the West Indies by the time of the Spanish conquest, and its cultivation was continued by the colonial Portuguese and Spanish. When the Portuguese arrived in 1500 south of Bahia, Brazil, they found cassava to be a staple crop of the Amerindians (Tupinamba), who processed it into bread and meal using techniques still employed today (Katz and Weaver 2003). The use of yuca as a staple food in many places of the Americas was translated into many images of yuca being used in pre-Columbian art; the Moche people often depicted yuca in their ceramics (Berrin and Larco 1997).

When the Portuguese imported slaves from Africa about 1550, they used cassava in the form of meal (farinha) for provision for their ships and began cultivating it along the coast of West Africa shortly thereafter (Katz and Weaver 2003). The Portuguese then introduced cassava to all of central Africa, East Africa, Madagascar, Ceylon, Malaya, India, and Indonesia (Katz and Weaver 2003). Cassava probably was first introduced to parts of Asia by the Spanish during their occupation of Philippines and distributed throughout tropical Asia by the nineteenth century (Katz and Weaver 2003).

Forms of the modern domesticated species can be found growing in the wild in the south of Brazil. While there are several wild Manihot species, all varieties of M. esculenta are cultigens.

Uses

Cassava roots are very rich in starch, and contain significant amounts of calcium (50 mg/100g), phosphorus (40 mg/100g), and vitamin C (25 mg/100g). However, they are poor in protein and other nutrients. Fresh, peeled roots may be 30 to 35 percent carbohydrate, but only 1 to 2 percent protein and less than 1 percent fat. In contrast, cassava leaves are a good source of protein (23 percent) if supplemented with the amino acid methionine despite containing cyanide. The quality of cassava protein is relatively good (Katz and Weaver 2003).

Cassava roots are cooked in various ways. The soft-boiled root has a delicate flavor and can replace boiled potatoes in many uses: as an accompaniment for meat dishes, or made into purées, dumplings, soups, stews, gravies, and so forth. Deep fried (after boiling or steaming), it can replace fried potatoes, with a distinctive flavor.

Tapioca and foufou are made from the starchy cassava root flour. Tapioca is an essentially flavor-less starchy ingredient, or fecula, produced from treated and dried cassava (manioc) root and used in cooking. It is similar to sago and is commonly used to make a milky pudding similar to rice pudding.

Cassava flour, also called tapioca flour or tapioca starch, can also replace wheat flour, and is so-used by some people with wheat allergies, such as coeliac disease. Boba tapioca pearls are made from cassava root. It is also used in cereals for which several tribes in South America have used it extensively. It is also used in making cassava cake, a popular pastry.

The juice of the bitter cassava, boiled to the consistence of thick syrup and flavored with spices, is called cassareep. It is used as a basis for various sauces and as a culinary flavoring, principally in tropical countries. It is exported chiefly from Guyana.

The leaves can be pounded to a fine chaff and cooked as a palaver sauce in Sierra Leone, usually with palm oil but vegetable oil can also be used. Palaver sauces contain meat and fish as well. It is necessary to wash the leaf chaff several times to remove the bitterness.

Cassava also is used to make alcoholic beverages.

In many countries, significant research has begun to evaluate the use of cassava as an ethanol biofuel. In China, dried tapioca are used among other industrial applications as raw material for the production of consumable alcohol and emerging non-grain feedstock of ethanol fuel, which is a form of renewable energy to substitute petrol (gasoline).

Cassava sometimes is used for medicinal purposes. The bitter variety of Manihot root is used to treat diarrhea and malaria. The leaves are used to treat hypertension, headache, and pain. Cubans commonly use cassava to treat irritable bowel syndrome; the paste is eaten in excess during treatment.

South America

In South America, cassava is used as a bread, as a roasted, granular meal (farinha, fariña), as a beer (chicha), a drink (manicuera), as a vegetable (boiled, boiled, and fried), and so forth (Katz and Weaver 2003). Farinha is part of a number of traditional dishes. Chicha is a mildly alcoholic beer made from both sweet and bitter cassava (Katz and Weaver 2003).

Bolivia. Cassava is very popular in Bolivia with the name of yuca and consumed in a variety of dishes. It is common, after boiling it, to fry it with oil and eat it with a special hot sauce known as llajwa or along with cheese and choclo (dried corn). In warm and rural areas, yuca is used as a substitute of bread in everyday meals. The capacity of cassava to be stored for a long time makes it suitable as an ideal and cheap reserve of nutrients. Recently, more restaurants, hotels, and common people are including cassava into their original recipes and everyday meals as a substitute for potato and bread.

Brazil. Cassava is heavily featured in the cuisine of Brazil. The dish vaca atolada ("mud-stranded cow") is a meat and cassava stew, cooked until the root has turned into a paste; and pirão is a thick gravy-like gruel prepared by cooking fish bits (such as heads and bones) with cassava flour, or farinha de mandioca. In the guise of farofa (lightly roasted flour), cassava combines with rice and beans to make the basic meal of many Brazilians. Farofa is also one of the most common side dishes to many Brazilian foods including feijoada, the famous salt-pork-and-black-beans stew. Boiled cassava is also made into a popular sweet pudding. Another popular sweet is cassava cake. After boiling, cassava may also be deep-fried to form a snack or side dish. In the north and northeast of Brazil, cassava is known as macaxeira and in the south and southeast of the country as mandioca or aipim.

Colombia. In Colombia, cassava is widely known as yuca among its people. In the Colombian northern coast region, it is used mainly in the preparation of Sancocho (a kind of rich soup) and other soups. The Pandebono bread made of the yuca dough. In the coastal region, is known especially in the form of "Bollo de yuca" (a kind of bread) or "enyucados." "Bollo de yuca" is a dough made of ground yuca that is wrapped in aluminum foil and then boiled, and is served with butter and cheese. "Enyucado" is a dessert made of ground boiled yuca, anise, sugar, and sometimes guava jam. In the Caribbean region of Colombia, it is also eaten roasted, fried, or boiled with soft homemade cheese or cream cheese and mainly as guarnition of fish dishes.

Suriname. In Suriname, cassava is widely used by the Creole, Indian, Javanese, and indigenous population. Telo is a popular dish, which is salted fish and cassava, where the cassava is steamed and deepfried. Other dishes with cassava include soups, dosi, and many others.

Ecuador. In Ecuador, cassava is referred to as yuca and included in a number of dishes. In the highlands, it is found boiled in soups and stews, as a side in place of potatoes, and reprocessed yuca is made into laminar fried chips called "yuquitos," which are a substitute for potato chips. Ecuadorians also make bread from yuca flour and mashed yuca root, including the extremely popular Bolitos de Yuca or Yuquitas, which range from balls of yuca dough formed around a heart of fresh cheese and deep-fried (found primarily in the north), to the simpler variety typical to Colombia which are merely baked balls of yuca dough. Yuca flour is sold in most markets. In the Amazon Basin, yuca is a main ingredient in chichaâa traditional fermented drink produced by the indigenous Quichua population. Yuca leaves, steamed, are part of the staple diet of the indigenous population in all areas where it is grown.

Paraguay. Cassava, or mandioca in Spanish, or mandi´o in Guarani, is a staple dish of Paraguay. It grows extremely well in the soil conditions throughout the country, and it is eaten at practically every meal. It is generally boiled and served as a side dish. It is also ground into a flour and used to make chipa, a bagel-shaped cheesy bread popular during holidays.

Peru. Cassava is also popular in Peru by the name of yuca, where it is used both boiled and fried. Boiled yuca is usually served as a side dish or in soup, while fried yuca is usually served together with onions and peppers as an appetizer or accompanying chicha.

Venezuela. Cassava bread (casabe) is a popular complement in traditional meals, as common as the arepas. Venezuelan Casabe is made by roasting ground cassava spread out as meter wide pancake over a hot surface (plancha). The result has the consistency of a cracker, and is broken in small pieces for consumption. There is also a sweet variety, called Naiboa, made as a sandwich of two casabe pancakes with a spread of Papelón in between. Naiboa also has a softer consistency. In general terms, mandioc is an essential ingredient in Venezuelan food, and can be found stewed, roasted, or fried as sides or complements. In Venezuela, cassava is also known as yuca. Yuca is actually the root of the cassava plant. Yuca is boiled, fried, or grilled to serve aside of main meals or to eat with cheese, butter, or margarine.

Central America

Belize. In Belize, cassava is traditionally made into "bammy," a small fried cassava cake inherited from the Garifuna. The cassava root is grated, rinsed well, dried, salted, and pressed to form flat cakes about 4 inches in diameter and 1/2-inch thick. The cakes are lightly fried, then dipped in coconut milk and fried again. Bammies are usually served as a starchy side dish with breakfast, with fish dishes or alone as a snack. The bile up (or boil up) is considered a cultural dish of the Belizean Kriol people. It is combination boiled eggs, fish, and/or pig tail, with number of ground foods, such as cassava, green plantains, yams, sweet potatoes, and tomato sauce. Cassava pone is a traditional Belizean Kriol and pan-West Indian dessert recipe for a classic cassava flour cake sometimes made with coconuts and raisins.

Ereba (cassava bread) is made from grated cassava or manioc. This is done in an ancient and time-consuming process involving a long, snake-like woven basket (ruguma), which strains the cassava of its juice. It is then dried overnight and later sieved through flat rounded baskets (hibise) to form flour that is baked into pancakes on a large iron griddle. Ereba is fondly eaten with fish, hudutu (pounded green and ripe plantains), or alone with gravy (lasusu).

El Salvador. In El Salvador, yuca is used in soups or is fried. Yuca Frita con Chicharrón is when the yuca is deep fried and served with curtido (a pickled cabbage, onion, and carrot topping) and pork rinds or pepesquitas (fried baby sardines). Yuca is sometimes served boiled instead of fried. Pan con pavo, translated to turkey with bread, is a warm turkey submarine sandwich similar to a hoagie. The turkey is marinated and then roasted with Pipil spices and handpulled. This sandwich is traditionally served with turkey, tomato, and watercress.

Costa Rica. In Costa Rica, yuca is widely used, both boiled in soups or fried and served with fried pieces of pork and lime. This is sold as a snack in most places you travel. When traveling by bus, the bus is often boarded by a local trying to sell "sandwich bagged" snacks of yuca, pork, and lime. Two main sources of food for locals in rural areas, who are living off resources within their own land, are yuca and plantain.

Panama. In Panama, yuca is sometimes used to make carimanolas. The boiled cassava is mashed into a dough and then filled with spiced meat. The meat-filled dumplings are deep fried to a golden brown. It is also used in brothy soups together with chicken, potatoes, and other vegetables.

Nicaragua. In Nicaragua, yuca is used in soups and in the Nicaraguan typical dish vigoron, which basically consists of boiled yuca, chicharron, and cabbage salad. Yuca is also used to make buñuelos and is one of the main ingredients in the national dish Vaho.

Caribbean

Cuba. Yuca, as cassava is called in Cuba, is a staple of Cuban cuisine. As in other Caribbean islands, it is ground up and made into a round shaped flat bread called casabe. As a side dish it can be boiled, covered with raw onion rings and sizzling garlic infused olive oil. It is also boiled then cut into strips and fried to make "yuca frita" (similar to french fries). Yuca is also one of the main ingredients in a traditional Cuban vegetarian stew called "Ajiaco," along with potatoes, malanga, boniato (sweet potato), plantain, Ãame, corn, and other vegetables. Cuban Buñuelos, a local variation of a traditional Spanish fritter (similar to the French beignet) is made with yuca and boniato (sweet potato) instead of flour. These are fried and topped off with anisette infused sugar syrup.

Haiti. Cassava (kassav) is a popular starch and common staple in Haiti where it is often eaten as part of a meal or by itself occasionally. It is usually eaten in bread form, often with peanut butter spread on the top or with milk. Cassava flour, known as Musa or Moussa is boiled to create a meal of the same name. Cassava can also be eaten with various stews and soups, such as squash soup (referred to as soup joumou). Cassava flour is also the flour used for Haitian cookies called BonBon Lamindon, a sweet melt-in-your-mouth cookie. The root vegetable yuca is grated, rinsed well, dried, salted, and pressed to form flat cakes about four inches in diameter and one-half-inch thick.

Dominican Republic. Cassava bread (casabe) is an often used as a complement in meals, much in the same way as wheat bread is used in Spanish, French, and Italian lunches. Also, as an alternative to side-dishes like french fries, arepitas de yuca are consumed, which are deep-fried buttered lumps of shredded cassava. Bollitos, similar to the Colombian ones, are also made. Also, a type of empanada called catibÃa has its dough made out of cassava flour. It is used for cassava bread (casabe), just peeled and boiled then eaten with olive oil and vinegar and served with other root vegetables like potatoes, ñame, yams, batata (sweet potatoes), and yautÃa (dasheen). Yuca, as it is widely known in the Dominican Republic, is also used to make (chulos), mainly in the Cibao region. The Yuca is grated, ingredients are added, and it is shaped into a cylindrical form, much like a croquette, and are finally fried. Also is an important ingredient for sancocho.

Puerto Rico. The root, in its boiled and peeled form, is also present in the typical Puerto Rican stew, the Sancocho, together with plantains, potatoes, yautÃa, among other vegetables. (It can also be eaten singly as an alternative to boiled potatoes or plantains.) It can be grounded and used as a paste (masa) to make a typically Puerto Rican Christmas favorite dish called "pasteles." It is somewhat similar to Mexican tamales in appearance, but is made with root vegetables, plantains, or yuca, instead of corn. Pasteles are rectangular and have a meat filling in the center, using chicken or pork. They are wrapped in a plantain leaf. "Masa" made from cassava is also used for "alcapurrias." These are shaped like lemons and are filled with meat similar to the pasteles but they are fried instead.

Jamaica. In Jamaica, cassava is traditionally made into "bammy," a small fried cassava cake inherited from the native Arawak Indians. The cassava root is grated, rinsed well, dried, salted, and pressed to form flat cakes about four inches in diameter and one-half-inch thick. The cakes are lightly fried, then dipped in coconut milk and fried again. Bammies are usually served as a starchy side dish with breakfast, with fish dishes or alone as a snack.

The Bahamas. In The Bahamas, cassava is eaten boiled, either alone or with sweet potatoes, cabbage, plantains, and meat. Alternatively, it is cooked in soups with okra or with dumplings, or baked into "cassava bread."

Eastern Caribbean. In the islands of the Eastern Caribbean, cassava is traditionally peeled and boiled and served with flour dumplings and other root vegetables like potatoes, yams, sweet potatoes, and dasheen.

Bermuda. Cassava pie is a traditional Christmas dish. The cassava is peeled and chopped finely, then mixed with egg, butter, and sugar. It is layered in a baking dish in alternate layers with chicken or pork. It is then baked in the oven, and leftovers may be fried. It is eaten as a savory dish, either on the side or as a main meal.

Using the traditional method of frying potato chips, bagged 'cassava chips' are produced and exported.

Africa

In sub-Saharan Africa, cassava is the second most important food crop (Katz and Weaver 2003). In the humid and sub-humid areas of tropical Africa, cassava is either a primary staple food or a secondary co-staple. Nigeria is the world's largest producer of cassava.

In West Africa, particularly in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, cassava is commonly prepared as eba or garri. The cassava is grated, pressed, fermented, and fried then mixed with boiling water to form a thick paste. In West Africa, the cassava root is pounded, mixed with boiling water to form a thick paste and cooked as eba. Historically, people economically forced to depend on cassava risk chronic poisoning diseases, such as tropical ataxic neuropathy (TAN), or such malnutrition diseases as kwashiorkor and endemic goitre. However, the price of cassava has risen significantly in the last half decade and lower-income people have turned to other carbohydrate-rich foods like rice and spaghetti.

In Central Africa, cassava is traditionally processed by boiling and mashing. The resulting mush can be mixed with spices and then cooked further or stored. A popular snack is made by marinating cassava in salted water for a few days and then grilling it in small portions.

In Tanzania and Kenya, cassava is known as mihogo in Swahili. Though the methods of cooking cassava vary from region to region, the main method is simply frying it. The skin of the root is removed and the remains are sectioned into small bite-size chunks that can then be soaked in water to aid in frying. Thereafter, the chunks are fried and then served, sometimes with a chili-salt mixture. This fried cassava is a very common street food as it is relatively cheap to buy, easy to prepare, and good to eat. The same applies to another very common roadside method where the cassava is lightly boiled and cut into straight pieces about 8-10 inches long. These pieces are then roasted over charcoal grills, served hot by splitting through the middle and applying the chili-salt mixture.

Cassava flour can also be made into a staple food with a consistency like polenta or mashed potatoes. The Swahili name for it is ugali, while the Kikuyu name for it is mwanga). It is also called fufu in Lingala.

Residents in the sub-Saharan nation of the Central African Republic have developed multiple, unique ways of utilizing the abundant cassava plant. In addition to the methods described above, local residents fry thin slices of the cassava root, resulting in a crunchy snack similar in look and taste to potato chips.

The root can be pounded into flour and made into bread or cookies. Many recipes have been documented and tested with groups of women in Mozambique and Zambia (Namwalizi 2006). This flour can also be mixed with precise amounts of salt and water to create a heavy liquid used as white paint in construction.

The cassava leaf is also soaked and boiled for extended periods of time to remove toxins and then eaten. Known as gozo in Sango and pondu in Lingala, the taste is similar to spinach.

Asia

Cassava preparation methods in most Asian countries involve boiling, baking, and frying, although another widespread practice is to peel, slice, and sun dry the roots and then make them into a flour by grinding (Katz and Weaver 2003).

China. The Chinese name for cassava is Mushu (æ¨è¯), literally meaning "tree potato". In the subtropical region of southern China, cassava is the fifth largest crop in term of production, after rice, sweet potato, sugar cane, and maize. China is also the largest export market of cassava produced in Vietnam and Thailand. Over 60 percent of cassava production in China is concentrated in a single province, Guangxi, averaging over seven million tons annually. Cassava in China is being increasingly used for ethanol fuel production.

India. In the state of Kerala, India, cassava is a secondary staple food. Boiled cassava is normally eaten with fish curry (kappayum meenum in Malayalam, which literally means casava with fish) or meat, and is a traditional favorite of many Keralites. Kappa biriyaniâcassava mixed with meatâis a popular dish in central Kerala. In Tamil Nadu, the National Highway 68 between Thalaivasal and Attur has many cassava processing factories (local name Sago Factory) alongside itâindicating an abundance of it in the neighborhood. In Tamil Nadu, it is called Kappa Kellangu or Marchini Kellangu. Cassava is widely cultivated and eaten as a staple food in Andhra Pradesh. The household name for processed cassava is saggu biyyam. Cassava is also deep fried in oil to make tasty homemade crisps, then sprinkled with flaked chillies or chilli powder and salt for taste. It is known as Mara Genasu in Kannada. Cassava Pearls {Sabu-Daana) is cassava-root starch and is used for making sweet milk puddings.

Indonesia. Cassava is widely eaten in Indonesia, where it is known as singkong, and used as a staple food during hard times but has lower status than rice. It is boiled or fried (after steaming), baked under hot coals, or added to kolak dessert. It is also fermented to make peuyeum and tape, a sweet paste which can be mixed with sugar and made into a drink, the alcoholic (and green) es tape. It is available as an alternative to potato crisps. Gaplek, a dried form of cassava, is an important source of calories in the off-season in the limestone hills of southern Java. Their young leaves also eaten as gulai daun singkong (cassava leaves in coconut milk), urap (javanese salad) and as main ingredient in buntil (javanese vegetable rolls).

Philippines. Tagalog speakers call cassava kamoteng kahoy (literal English means "wood yam"). Visayans call cassava balanghoy. Cassava is mainly prepared as a dessert. It is also steamed and eaten plain. Sometimes it is steamed and eaten with grated coconut. The most popular dessert is the cassava cake/pie, which uses grated cassava, sugar, coconut milk, and coconut cream. The leaves are also cooked and eaten.

Sri Lanka. Though cassava is not widely cultivated in Sri Lanka, tapioca, called maniyok, is used as a supplementary food. Some Sri Lankans take it as breakfast. Often root is taken fresh and cleaned boiled in an open pot. Some preparations add saffron to make it little yellowish in color. Eating maniyok with scraped coconut is common. Another popular preparation adds "Katta Sambol" (red hot chili mix) with boiled tapioca. Maniyok curry is a good side dish when taking rice, a Sri Lankan staple food. There is belief among Sri Lankans that one should not take maniyok together with ginger, which will cause food poisoning. Leaves of the plant are also prepared as side dish and called "Malluma." Dried, powdered, and starched tapioca are widely used in Sri Lanka.

Vietnam. Cassava's name in Vietnamese is "Khoai Mì" (Southern). It is planted almost everywhere in Vietnam and its root is among the cheapest sources of food there. The fresh roots are sliced into thin pieces and then dried in the sun. Tapioca is the most valuable product from processed cassava roots there.

Animal feed

Cassava is used worldwide for animal feed as well.

Cassava hay is hay that is produced at a young growth stage, 3 to 4 months, and is harvested about 30 to 45 centimeters above ground, sun-dried for 1 to 2 days until having a final dry matter of at least 85 percent. The cassava hay contains high protein content (20-27 percent Crude Protein) and condensed tannins (1.5-4 percent CP). It is used as a good roughage source for dairy, beef, buffalo, goats, and sheep by either direct feeding or as a protein source in the concentrate mixtures.

Cassava Pests

In Africa the cassava mealybug (Phenacoccus manihoti) and cassava green mite (Mononychellus tanajoa) can cause up to 80 percent crop loss, which is extremely detrimental to the production of subsistence farmers. These pests were rampant in the 1970s and 1980s but were brought under control following the establishment of the Biological Control Centre for Africa of the IITA. The Centre investigated biological control for cassava pests; two South American natural enemies Apoanagyrus lopezi (a parasitoid wasp) and Typhlodromalus aripo (a predatory mite) were found to effectively control the cassava mealybug and the cassava green mite, respectively.

The cassava mosaic virus causes the leaves of the cassava plant to wither, limiting the growth of the root. The virus is spread by the whitefly and by the transplanting of diseased plants into new fields. Sometime in the late 1980s, a mutation occurred in Uganda that made the virus even more harmful, causing the complete loss of leaves. This mutated virus has been spreading at a rate of 50 miles per year, and as of 2005 may be found throughout Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the Congo.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Akindahunsi, A. A., F. E. Grissom, S. R. Adewusi, O. A. Afolabi, S. E. Torimiro, and O. L. Oke. 1998. Parameters of thyroid function in the endemic goitre of Akungba and Oke-Agbe villages of Akoko area of southwestern Nigeria. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 27(3-4): 239â42. PMID 10497657. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- Aregheore E. M, and O. O. Agunbiade. 1991. The toxic effects of cassava (manihot esculenta grantz) diets on humans: a review. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. 33: 274â275.

- Australian National University (ANU). 2007. New method of cyanide removal to help millions. Australian National University. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- Bender, D. A., and A. E. Bender. 2005. A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198609612.

- Berrin, K., and Larco Museum. 1997. The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500018022.

- Bradbury, J. H. 2006. Simple wetting method to reduce cyanogen content of cassava flour. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 19(4): 388â393. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- Cereda, M. P., and M. C. Y. Mattos. 1996. Linamarin: The toxic compound of cassava. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins 2: 6â12.

- Fauquet, C., and D. Fargette. 1990. African cassava mosaic virus: Etiology, epidemiology, and control. Plant Disease 74(6): 404-11. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). 2007. June 2003 cassava market assessment. FAO. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- Herbst, S. T. 2001. The New Food Lover's Companion: Comprehensive Definitions of Nearly 6,000 Food, Drink, and Culinary Terms. Barron's Cooking Guide. Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0764112589.

- Katz, S. H., and W. W. Weaver. 2003. Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. New York: Schribner. ISBN 0684805685

- Namwalizi, R. 2006. Cassava Is The Root. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781411671133.

- Olsen, K. M., and B. A. Schaal. 1999. Evidence on the origin of cassava: Phylogeography of Manihot esculenta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) 96(10): 5587-5590.

- Padmaja, G. 1995. Cyanide detoxification in cassava for food and feed uses. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 35: 299â339. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- Pope, K., M. E. D. Pohl, J. G. Jones, D. L. Lentz, C. von Nagy, F. J. Vega, I. R. Quitmyer. 2001. Origin and environmental setting of ancient agriculture in the lowlands of Mesoamerica. Science 292(5520): 1370-1373. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- University of Colorado at Boulder (UCB). 2007. CU-Boulder archaeology team discovers first ancient manioc fields in Americas. University of Colorado August 20, 2007. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- White W. L. B., D. I. Arias-Garzon, J. M. McMahon, and R. T. Sayre. 1998. Cyanogenesis in cassava: The role of hydroxynitrile lyase in root cyanide production. Plant Physiol. 116: 1219â1225. Retrieved October 23, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

This article incorporates text from the public domain 1911 edition of The Grocer's Encyclopedia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.