Difference between revisions of "Serfdom" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (40 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Edboard}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{copyedited}} | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| − | [[Image:Costumes of Slaves or Serfs from the Sixth to the Twelfth Centuries.png|thumb|right|Costumes of slaves or serfs, from the sixth to the twelfth centuries, collected by H. de Vielcastel from original documents in European libraries.]] | + | [[Image:Costumes of Slaves or Serfs from the Sixth to the Twelfth Centuries.png|thumb|right|250 px|Costumes of slaves or serfs, from the sixth to the twelfth centuries, collected by H. de Vielcastel from original documents in European libraries.]] |

| − | '''Serfdom''' is the [[socio-economic]] status of unfree [[peasant]]s under [[feudalism]], and specifically relates to [[Manorialism]]. It was a condition of [[Debt bondage|bondage]] or modified [[slavery]] which developed primarily during the [[High Middle Ages]] in Europe | + | '''Serfdom''' is the [[socio-economic]] status of unfree [[peasant]]s under [[feudalism]], and specifically relates to [[Manorialism]]. Serfdom was the enforced [[labor]] of serfs on the fields of landowners, in return for their protection as well as the right to work on their [[lease]]d fields. It was a condition of [[Debt bondage|bondage]] or modified [[slavery]] which developed primarily during the [[High Middle Ages]] in [[Europe]], evolving from agricultural slavery of the late [[Roman Empire]], it flourished in Europe during the Middle Ages, lasting until the nineteenth century. Serfdom also appeared with feudalism in [[China]], [[Japan]], [[India]], [[pre-Columbian Mexico]], and elsewhere. |

| − | Serfdom involved | + | Serfdom involved work not only on fields, but various [[agriculture]]-related works, like [[forestry]], [[mining]], [[transportation]] (both land and river-based), crafts, and even in production. Manors formed the basic unit of [[society]] during this period, and both the lord and his serfs were bound legally, economically, and socially. Serfs were laborers who were bound to the land; they formed the lowest [[social class]] of the feudal society. Serfs were also defined as people in whose labor landowners held property rights. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | After the [[Renaissance]], serfdom became increasingly rare in most of [[Western Europe]] but grew strong in [[Central Europe|Central]] and [[Eastern Europe]], where it had previously been less common. In [[England]], it lasted legally up to the 1600s and in [[France]] until 1789. There were native-born [[Scotland|Scottish]] serfs until 1799, when [[coal]] [[mining|miners]] previously kept in serfdom gained [[emancipation]]. In Eastern Europe, the institution persisted until the mid-nineteenth century. It persisted in [[Austria-Hungary]] until 1848, and was abolished in [[Russian Empire|Russia]] only in 1861. [[Tibet]] is believed to be the last place to have abolished serfdom, in 1959. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Although the end of serfdom means freedom, in many cases the transition to a new social order was far from smooth. Those in power often "freed" their serfs without concern for their well-being, caring only for their own situation. Merely breaking apart a system that has injustices and inequalities does not necessarily result in positive advances. The end of serfdom and all its problems is but one step toward the establishment of a harmonious and just society. | ||

| + | [[Image:Bernstorff and Frederick VI.JPG|thumb|right|250 px|Andreas Peter Bernstorff and Frederik VI of Denmark. detail of engraving celebrating the abolishment of serfdom, c. 1800]] | ||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| + | The word '''serf''' originated from the [[Middle French]] "serf," and can be traced farther back to the [[Latin]] ''servus,'' meaning "[[slave]]." In [[Late Antiquity]] and most of the [[Middle Ages]], what are now call serfs were usually designated in Latin as ''[[colonus (person)|coloni]]'' (sing. ''colonus''). As slavery gradually disappeared and the legal status of these ''servi'' became nearly identical to that of ''coloni,'' the term changed meaning into the modern concept of "serf." Serfdom is distinguished from slavery by rights the serfs held by a custom generally recognized as inviolable, by the [[social structure]] that made the [[peasant]]s servile in a group rather than individually, and by the fact that they could usually pass the right to work their land on to a son. | ||

| − | + | ==The role of serfs== | |

| − | |||

| − | ==The | ||

[[Image:Munkácsy Tépéscsinálók.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Peasants during the winter (''Pluckmakers'' by [[Mihály Munkácsy]], 1871)]] | [[Image:Munkácsy Tépéscsinálók.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Peasants during the winter (''Pluckmakers'' by [[Mihály Munkácsy]], 1871)]] | ||

| − | The essential characteristic of a manorial society was the near-total subordination of the | + | The essential characteristic of a [[manorial society]] was the near-total subordination of the [[peasant]]s to the economic authority and [[jurisdiction]] of the landlord. However, not all peasants were completely subsumed under serfdom. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In medieval times, in [[England]], vast amounts of land belonged to the [[Church]]; other land was owned privately. Indispensable for the survival of small landowners was the common land (''Allmende'' in French), which was collective arable and forest land used for cultivation and for feeding livestock. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Landholders consisted of the [[nobility]], the Church, and [[royalty]]. Serfs were allowed to work certain plots of land in exchange for a percentage of the product they produced. While most serfs were farmers, some were craftsmen, such as blacksmiths or millers. In most serfdoms, serfs were legally part of the land, and if the land was sold, they were sold with it. Medieval manors consisted of a [[manor house]], where the landlord, [[knight]], or [[baron]] lived, and a village consisting of peasant houses. These homes were actually one-bedroom huts made from wooden beams, mud, and straw. During the winter months, warmth was made by allowing the farm animals ([[goat]]s, [[sheep]], [[chicken]]s, [[goose|geese]], and often [[cattle]]) to sleep inside. | |

| − | + | The lives of serfs were very strenuous. The lord needed to maintain his authority in order to maintain the [[social structure]]. The [[priest]] was the bedrock of village life and all members of the [[community]] were dependent on him for their religious instruction and obligations. The priest could “proclaim [a serf’s duties], more for the society than for the ploughman; such total servitude is indeed useful to everyone.”<ref>Allen J. Frantzen and Douglas Moffat (eds.), ''The World of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England'' (Glasgow: Cruithne Press, 1994), p. 60.</ref> Lords and priests who were able to insist that the serf’s role was indeed essential and important to the survival of the community often perpetuated this system. | |

| − | + | The serfs had a place in feudal society in much the same fashion as a [[baron]] or a [[knight]]. A serf's place was that, in return for protection, he would reside upon and work a parcel of land held by his lord. There was, thus, a degree of reciprocity in the manorial system. The period rationale was that a serf "worked for all," while a knight or baron "fought for all," and a churchman "prayed for all;" thus everyone had his place. The serf worked harder than the others, and was the worst fed and paid, but at least he had his place and, unlike in [[slavery]], he had his own land and properties. A manorial lord could not sell his serfs as a Roman might sell his slaves. On the other hand, if he chose to dispose of a parcel of land, the serf or serfs associated with that land went with it to serve their new lord. Further, a serf could not abandon his lands without permission, nor could he sell them. | |

| − | + | ==History== | |

| + | Social institutions similar to serfdom were known in [[ancient history|ancient times]]. The status of the [[helots]] in the [[ancient Greece|ancient Greek]] [[city-state]] of [[Sparta]] resembled that of the medieval serfs, as did the condition of the peasants working on government lands in [[ancient Rome]]. These Roman peasants, known as ''[[colonus (person)|coloni]],'' or "tenant farmers," are some of the possible precursors of the serfs. The [[Germanic tribe]]s invading the [[Roman Empire]] for the most part displaced wealthy Romans as the landlords but left the [[economic system]] itself intact. | ||

| − | + | However, medieval serfdom really began with the breakup of the [[Carolingian Empire]] around the tenth century. The demise of this empire, which had ruled much of the western Europe for more than 200 years, was followed by a long period during which no strong central governments existed in most of Europe. During this period, powerful [[feudalism|feudal lords]] encouraged the establishment of serfdom as a source of agricultural [[labor]]. Serfdom, indeed, was an institution that reflected a fairly common practice whereby great landlords were assured that others worked to feed them and were held down, legally and economically, while doing so. This arrangement provided most of the agricultural labor throughout the [[Middle Ages]]. Parts of Europe however, including much of [[Scandinavia]], never adopted many feudal institutions, including serfdom. | |

| − | + | In the later Middle Ages, serfdom began to disappear west of the [[Rhine]] even as it spread through [[Eastern Europe]]. This was one important cause for the deep differences between the societies and economies of Eastern and Western Europe. In [[Western Europe]], the rise of powerful [[monarch]]s, towns, and an improving [[economy]] weakened the [[manorial system]] through the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and serfdom was rare following the [[Renaissance]]. | |

| − | + | Serfdom in Western Europe came largely to an end in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, because of changes in the economy, population, and laws governing lord-tenant relations in Western European nations. The [[enclosure]] of manor fields for livestock grazing and for larger arable plots made the economy of serfs’ small strips of land in open fields less attractive to the landowners. Furthermore, the increasing use of [[money]] made tenant farming by serfs less profitable; for much less than it cost to support a serf, a lord could now hire workers who were more skilled and pay them in cash. Paid labor was also more flexible since workers could be hired only when they were needed. | |

| − | Another important factor in the decline of serfdom was industrial | + | At the same time, increasing unrest and uprisings by serfs and peasants, like [[Peasants' Revolt (1381)|Tyler’s Rebellion]] in England in 1381, put pressure on the nobility and the clergy to reform the system. As a result serf and peasant demands were accommodated to some extent by the gradual establishment of new forms of leasing the land and increased personal liberties. Another important factor in the decline of serfdom was industrial development—especially the [[Industrial Revolution]]. With the growing profitability of [[industry]] farmers wanted to move to towns to receive higher wages than those they could earn working in the fields, while landowners also invested in the more profitable industry. This also led to the growing process of [[urbanization]]. |

[[Image:Zboze Placi.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Grain pays]] | [[Image:Zboze Placi.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Grain pays]] | ||

| − | Serfdom reached [[Eastern Europe]]an countries relatively later than Western | + | Serfdom reached [[Eastern Europe]]an countries relatively later than Western Europe—it became dominant around the fifteenth century. Before that time, Eastern Europe had been much less populated than Western Europe. Serfdom developed in Eastern Europe after the [[Black Death]] epidemics, which not only stopped the [[human migration|migration]] but depopulated Western Europe. The resulting large land-to-labor ratio combined with Eastern Europe's vast, sparsely populated areas gave the lords an incentive to bind the remaining peasantry to their land. With increased demand for agricultural products in Western Europe during the later era when Western Europe limited and eventually abolished serfdom, serfdom remained in force throughout Eastern Europe during the seventeenth century so that [[nobility]]-owned estates could produce more agricultural products (especially [[cereal|grain]]) for the profitable export market. |

| − | + | Such Eastern European countries include [[Prussia]] ([[Prussian Ordinances]] of 1525), [[Austria]], [[Hungary]] (laws of late fifteenth, early sixteenth centuries), the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]] (''[[szlachta]]'' privileges of early sixteenth century) and the [[Russian Empire]] (laws of late sixteenth/first half of seventeenth century). This also led to the slower industry development and urbanization of those regions. Generally, this process, referred to as "second serfdom" or "export-led serfdom," which persisted until the mid-nineteenth century, became very repressive and substantially limited serfs' rights.[[Image:Zboze Nie Placi.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Grain doesn't pay. Those two pictures illustrate the notion that agriculture, once extremely profitable to the nobles ''(szlachta)'' in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, became much less profitable from the second half of seventeenth century onwards.]] | |

| − | + | In many of these countries, serfdom was abolished during the [[Napoleonic Wars|Napoleonic invasions]] of the early nineteenth century. Serfdom remained the practice on the most part of territory of Russia until February 19, 1861, though in Russian Baltic provinces it has been abolished in the beginning of nineteenth century ([[Russian history, 1855-1892|Russian Serfdom Reforms]]). [[Russian serfdom]] was perhaps the most notable among the Eastern European experiences, as it was never influenced by German law and migrations, and the serfdom and manorialism systems were forced by the crown ([[Tsar]]), not the nobility. | |

| − | + | Beyond Europe, a number of other regions including much of [[Asia]] also established [[Feudalism|feudal]] societies, some of which incorporated serfdom although not uniformly. According to Joseph R. Strayer, feudalism was found in the societies of the [[Byzantine Empire]], [[Iran]], ancient [[Mesopotamia]], [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]] (Sixth to Twelfth dynasty), [[Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent|Muslim India]], [[China]] ([[Zhou Dynasty]], end of [[Han Dynasty]], Tibet (thirteenth century-1959), and [[Qing Dynasty]] (1644-1912), and in [[Japan]] during the [[Shogunate]]. [[Tibet]] is believed to be the last place to have abolished serfdom, in 1959. | |

| − | + | ==The system of serfdom== | |

| − | + | A freeman became a serf usually through force or necessity. Sometimes [[Fee simple|freeholder]] or [[allodial]] owners were intimidated into dependency by the greater physical and legal force of a local baron. Often, a few years of crop failure, a [[war]], or [[brigandage]] might leave a person unable to make his own way. In such a case a bargain was struck with the lord. In exchange for protection, service was required, in payment and/or with [[labor]]. These bargains were formalized in a ceremony known as "bondage," in which a serf placed his head in the seigneur's hands, parallel to the ceremony of "homage" where a vassal placed his hands between those of his lord. These oaths bonded the seigneur to their new serf and outlined the terms of their agreement.<ref>Marc Bloch, ''Feudal Society, Volume 1: The Growth of Ties of Dependence'' (University Of Chicago Press, 1964, ISBN 978-0226059785).</ref> Often these bargains were severe. A seventh century [[Old English language|Anglo Saxon]] “Oath of Fealty" states <blockquote>By the Lord before whom this sanctuary is holy, I will to N. be true and faithful, and love all which he loves and shun all which he shuns, according to the laws of God and the order of the world. Nor will I ever with will or action, through word or deed, do anything which is unpleasing to him, on condition that he will hold to me as I shall deserve it, and that he will perform everything as it was in our agreement when I submitted myself to him and chose his will.</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | A freeman became a serf usually through force or necessity. Sometimes freeholder or allodial owners were intimidated into dependency by the greater physical and legal force of a local baron. Often a few years of crop failure, a war or [[brigandage]] might leave a person unable to make his own way. In such a case a bargain was struck with the lord. In exchange for protection, service was required, in payment and/or with labor. These bargains were formalized in a ceremony known as "bondage" in which a serf placed his head in the seigneur's hands, parallel to the ceremony of "homage" where a vassal placed his hands between those of his lord. These oaths bonded the seigneur to their new serf and outlined the terms of their agreement. <ref>Marc Bloch | ||

| − | Moreover, serfdom was inherited. By taking on the duties of serfdom, serfs bound not only themselves but all of their future heirs. | + | To become a serf was a commitment that invaded all aspects of the serf’s life. Moreover, serfdom was inherited. By taking on the duties of serfdom, serfs bound not only themselves but all of their future heirs. |

| − | === | + | ===Classes=== |

| − | + | The class of [[peasant]] was often broken down into smaller categories. The distinctions between these classes were often less clear than would be suggested by the different names encountered for them. Most often, there were two types of peasants--freemen and villeins. However, both half-villeins, cottars or cottagers, and slaves made up a small percentage of workers. | |

| − | The class of [[peasant]] was often broken down into smaller categories. The distinctions between these classes were often less clear than would be suggested by the different names encountered for them. Most often, there were two types of peasants - freemen and villeins. However, both half-villeins, cottars or cottagers, and slaves made up a small percentage of workers. | ||

====Freemen==== | ====Freemen==== | ||

| − | Freemen were essentially rent-paying [[tenant]] farmers who owed little or no service to the lord. In parts of eleventh-century [[England]] these freemen made up only ten percent of the peasant population and in the rest of Europe their numbers were relatively small. | + | Freemen were essentially [[rent]]-paying [[tenant]] farmers who owed little or no service to the lord. In parts of eleventh-century [[England]] these freemen made up only ten percent of the peasant population and in the rest of Europe their numbers were relatively small. |

====Villeins==== | ====Villeins==== | ||

| − | A villein was the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages. Villeins had more rights and status than those held as slaves, but were under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from the freeman. Villeins generally | + | A villein was the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages. Villeins had more rights and status than those held as slaves, but were under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from the freeman. Villeins generally [[rent]]ed small homes, with or without land. As part of the [[contract]] with their [[landlord]], they were expected to use some of their time to farm the lord's fields and the rest of their time was spent farming their own land. Like other types of serfs, they were required to provide other services, possibly in addition to a rent of [[money]] or [[goods]]. These services could be very onerous. Villeins were tied to the land and could not move away without their lord's consent. However, in other regards, they were free men in the eyes of the law. Villeins were generally able to have their own property, unlike slaves. Villeinage, as opposed to other forms of serfdom, was most common in Western European [[feudalism]], where land ownership had developed from roots in [[Roman law]]. |

A variety of kinds of villeinage existed in the European Middle Ages. Half-villeins received only half as many strips of land for their own use and owed a full complement of [[labor]] to the lord, often forcing them to rent out their services to other serfs to make up for this hardship. Villeinage was not, however, a purely exploitative relationship. In the Middle Ages, land guaranteed [[sustenance]] and survival, and being a villein guaranteed access to land. Landlords, even where legally able to, rarely evicted villeins because of the value of their labor. Villeinage was much preferable to being a vagabond, a slave, or an un-landed laborer. | A variety of kinds of villeinage existed in the European Middle Ages. Half-villeins received only half as many strips of land for their own use and owed a full complement of [[labor]] to the lord, often forcing them to rent out their services to other serfs to make up for this hardship. Villeinage was not, however, a purely exploitative relationship. In the Middle Ages, land guaranteed [[sustenance]] and survival, and being a villein guaranteed access to land. Landlords, even where legally able to, rarely evicted villeins because of the value of their labor. Villeinage was much preferable to being a vagabond, a slave, or an un-landed laborer. | ||

| − | In many medieval countries, a villein could gain freedom by escaping to a city and living there for more than a year; but this avenue involved the loss of land and agricultural livelihood, a prohibitive price unless the landlord was especially tyrannical or conditions in the village were unusually difficult. Villeins newly arrived in the city in some cases took to crime for survival, which gave the alternate spelling "[[villain]]" its modern meaning. | + | In many medieval countries, a villein could gain freedom by escaping to a [[city]] and living there for more than a year; but this avenue involved the loss of land and agricultural livelihood, a prohibitive price unless the landlord was especially tyrannical or conditions in the village were unusually difficult. Villeins newly arrived in the city in some cases took to [[crime]] for survival, which gave the alternate spelling "[[villain]]" its modern meaning. |

====Cottagers==== | ====Cottagers==== | ||

| Line 90: | Line 71: | ||

====Slaves==== | ====Slaves==== | ||

The last type of serf was the [[Slavery|slave]]. Slaves had the fewest [[rights]] and benefits from the manor and were also given the least. They owned no land, worked for the lord exclusively and survived on donations from the landlord. | The last type of serf was the [[Slavery|slave]]. Slaves had the fewest [[rights]] and benefits from the manor and were also given the least. They owned no land, worked for the lord exclusively and survived on donations from the landlord. | ||

| − | It was always in the interest of the lords to prove that a servile arrangement existed, as this provided them with greater rights to fees and | + | It was always in the interest of the lords to prove that a servile arrangement existed, as this provided them with greater rights to fees and [[tax]]es. The legal status of a man was a primary issue in many of the manorial court cases of the period. |

| − | ===The serf's | + | ===Duties=== |

| + | The usual serf (not including slaves or cottars) paid his fees and taxes in the form of seasonally appropriate [[labor]]. Usually, a portion of the week was devoted to plowing his lord's fields ([[demesne]]), harvesting crops, digging ditches, repairing fences, and often working in the manor house. The lord’s demesne included more than just fields: It included all grazing rights, forest produce (nuts, fruits, timber, and forest animals), and fish from the stream; the lord had exclusive rights to these things. The rest of the serf’s time was devoted to tending his or her own fields, crops and animals in order to provide for his or her family. Most manorial work was segregated by [[gender]] during the regular times of the year; however, during the [[harvest]], the whole family was expected to work the fields. | ||

| − | + | [[Corvée]], or corvée labor, was a type of annual tax payable as labor to the monarch, vassal, overlord, or lord of the manor. It was used to complete royal projects, to maintain roads and other public facilities, and to provide labor to maintain the feudal estate. | |

| − | The difficulty of a serf's life derived from the fact that his work for his lord coincided with, and took precedence over, the work he had to perform on his own lands: | + | The difficulty of a serf's life derived from the fact that his work for his lord coincided with, and took precedence over, the work he had to perform on his own lands: When the lord's crops were ready to be harvested, so were his own. On the other hand, the serf could look forward to being well fed during his service; it was a poor lord who did not provide a substantial meal for his serfs during the harvest and planting times. In exchange for this work on the lord's property, the serf had certain privileges and rights. They were allowed to gather [[deadwood]] from their lord’s forests. For a fee, the serfs were allowed to use the manor’s [[mill]]s and ovens. |

| − | In addition to service, a serf was required to pay certain [[ | + | In addition to service, a serf was required to pay certain [[tax]]es and fees. Taxes were based on the assessed value of his lands and holdings. Fees were usually paid in the form of foodstuffs rather than cash. The best ration of wheat from the serf’s harvest always went to the landlord. For the most part, [[hunting]] on the lord’s property was prohibited for the serfs. On [[Easter]] Sunday the peasant family owed an extra dozen eggs, and on [[Christmas]] a goose was expected as well. When a family member died, extra taxes were paid to the manor for the cost of that individual's labor. Any young woman who wished to marry a serf outside of her manor was forced to pay a fee for the lost labor. It was also a matter of discussion whether serfs could be required by law in times of [[war]] or conflict to fight for their lord's land and property. |

| − | + | The restraints of serfdom on personal and economic choice were enforced through various forms of [[manorialism|manorial]] common law and the manorial administration and court. | |

| − | The restraints of serfdom on personal and economic choice were enforced through various forms of manorial common law and the manorial administration and court. | ||

| − | + | ===Benefits=== | |

| + | Within his constraints, a serf had some freedom. Though the common wisdom is that a serf owned "only his belly"—even his clothes were the property, in law, of his lord—a serf might still accumulate personal [[property]] and [[wealth]], and some serfs became wealthier than their free neighbors, although this was rather an exception to the general rule. A well-to-do serf might even be able to buy his freedom. | ||

| − | + | Serfs could raise what they saw fit on their lands (within reason—a serf's [[tax]]es often had to be paid in [[wheat]], a notoriously difficult crop), and sell the surplus at [[market]]. Their [[heir]]s were usually guaranteed an [[inheritance]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Serfs could raise what they saw fit on their lands (within | ||

The landlord could not dispossess his serfs without cause and was supposed to protect them from the depredations of [[outlaw]]s or other lords, and he was expected to support them by charity in times of [[famine]]. | The landlord could not dispossess his serfs without cause and was supposed to protect them from the depredations of [[outlaw]]s or other lords, and he was expected to support them by charity in times of [[famine]]. | ||

==Variations== | ==Variations== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Yuriev day.jpg|275px|thumb|left|''A Peasant Leaving His Landlord on [[Yuriev Day]]'', painting by [[Sergei V. Ivanov]].]] | |

Specifics of serfdom varied greatly through time and region. In some places, serfdom was merged with or exchanged for various forms of [[taxation]]. | Specifics of serfdom varied greatly through time and region. In some places, serfdom was merged with or exchanged for various forms of [[taxation]]. | ||

| − | The amount of labor required varied. In [[Poland]], for example, it was few days a year in the thirteenth century; one day per week in the fourteenth century; four days per week in the seventeenth century and six days per week in the eighteenth century. Early serfdom in Poland was most limited on the royal territories ''([[królewszczyzny]])'' | + | The amount of [[labor]] required varied. In [[Poland]], for example, it was few days a year in the thirteenth century; one day per week in the fourteenth century; four days per week in the seventeenth century and six days per week in the eighteenth century. Early serfdom in Poland was most limited on the royal territories ''([[królewszczyzny]])''. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Sometimes, serfs served as soldiers in the event of conflict and could earn freedom or even [[ennoblement]] for valor in combat. In other cases, serfs could purchase their freedom, be [[manumission|manumitted]] by their enlightened or generous owners, or flee to towns or newly-settled land where few questions were asked. Laws varied from country to country: In [[England]], a serf who made his way to a [[charter]]ed town and evaded recapture for a year and a day obtained his freedom. | |

| − | + | In [[Russia]], the legal code of [[Ivan III of Russia]], ''[[Sudebnik]]'' (1497), restricted the mobility of peasants. Their right to leave their master was limited to a period of one week before and after the so-called [[Yuri's Day]] (November 26). A temporary (''Заповедные лета,'' or [[Prohibition years]]) and later an open-ended prohibition for peasants to leave their masters was introduced by the ''[[ukase]]'' of 1597, which also defined the so-called [[fixed years]] (''Урочные лета'', or ''urochniye leta''), or the five-year time frame for search of the runaway peasants. This was later extended to ten years. | |

| − | + | In [[Tibet]], the greater part of the rural population—some 700,000 of an estimated total population of 1,250,000—were serfs as late as 1953. Tied to the land under an essentially [[feudal]] system, they were allotted only a small parcel to grow their own food, spending most of their time laboring for the [[monastery|monasteries]] and individual high-ranking [[lama]]s, or for a secular [[aristocracy]]. However, Goldstein has noted that not all serfs were destitute, some could amass considerable [[wealth]] and even own their own land.<ref>Melvyn C. Goldstein, ''A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State'' (University of California Press, 1991, ISBN 0520075900), p. 5.</ref> There were several types of serf sub-status of which one of the most important was the "human lease" which enabled a serf to acquire a degree of personal freedom because, despite retaining the concept of lordship, the serfs were not bound to a landed estate.<ref>Melvyn C. Goldstein, "Serfdom and mobility: an examination of the institution of 'human lease' in traditional Tibetan society" ''Journal of Asian Studies'' 30, (3) (May 1971): 521-534.</ref> After China took over Tibet and the [[Dalai Lama]] fled to [[India]], the [[communism|communist]] government started to abandon serfdom, allowing serfs to grow their own crops and vegetables, albeit under the communist system.<ref>Anna Louise Strong, ''When Serfs Stood Up in Tibet,'' p. 265.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | In | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==The decline of serfdom== | ==The decline of serfdom== | ||

| − | |||

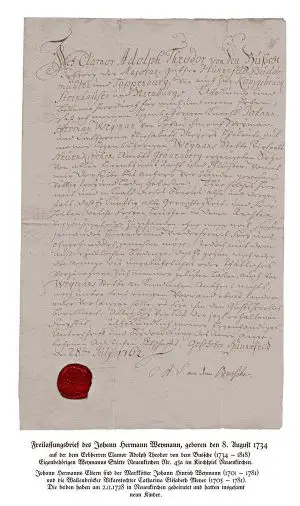

[[Image:Freilassungsbrief Weymann.jpg|thumb|End of serfdom: a German „Freilassungsbrief“ (Letter for the End of a serfdom) from 1762]] | [[Image:Freilassungsbrief Weymann.jpg|thumb|End of serfdom: a German „Freilassungsbrief“ (Letter for the End of a serfdom) from 1762]] | ||

| − | Serfdom became progressively less common through the Middle Ages, particularly after the [[Black Death]] reduced the rural population and increased the bargaining power of workers. Furthermore, the lords of many manors were willing (for payment) to ''manumit'' ("release") their serfs | + | Serfdom became progressively less common through the [[Middle Ages]], particularly after the [[Black Death]] reduced the rural population and increased the bargaining power of workers. Furthermore, the lords of many manors were willing (for payment) to ''manumit'' ("release") their serfs. |

| − | + | Serfdom had largely died out in [[England]], by 1500, as a personal status, but land held by serf tenure (unless enfranchised) continued to be held by what was henceforth known as a [[Copyhold|copyhold tenancy]], which was not abolished until 1925. During the [[Late Middle Ages]], [[peasant]] unrest led to outbreaks of violence against landlords. In May 1381, the English peasants [[English peasants' revolt of 1381|revolted]] because of the heavy [[tax]] placed upon them by [[Parliament]]. There were similar occurrences at around the same time in [[Castille]], [[Germany]], northern [[France]], [[Portugal]], and [[Sweden]]. Although these [[Popular revolt in late medieval Europe|peasant revolts]] were often successful, it usually took a long time before legal systems were changed. In France, this occurred on August 11, 1789, with the “Decree Abolishing the Feudal System.” This decree abolished the manorial system completely. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The beginning of the eradication of the [[feudal]] system marks an era of rapid change in Europe. [[Tax]]es levied by the state took the place of [[labor]] dues levied by the lord. The change in status following the [[enclosure]] movements beginning in the later eighteenth century, in which various lords abandoned the open field farming of previous centuries in exchange for, essentially, taking all the best land for themselves and "freeing" their serfs, may well have made serfdom a lifestyle desperately to be wished for by many peasant families. | |

| + | Although serfdom began its decline in Europe in the Middle Ages, it took many hundreds of years to disappear completely. In addition, the struggles of the working class during the [[Industrial Revolution]] has been compared with the struggles of the serfs during the Middle Ages. Serfdom is an institution that has been commonplace in human history; however, it has not always been of the same nature. In parts of the world today, [[forced labor]] is still used. | ||

| − | + | Emancipation from serfdom was achieved in various countries on the following dates: | |

{{col-begin}} | {{col-begin}} | ||

{{col-break}} | {{col-break}} | ||

*[[Wallachia]]: 1746 | *[[Wallachia]]: 1746 | ||

*[[Moldavia]]: 1749 | *[[Moldavia]]: 1749 | ||

| − | *[[Kingdom of Savoy|Savoy]]: 19 | + | *[[Kingdom of Savoy|Savoy]]: December 19, 1771 |

| − | *[[Habsburg Monarchy|Austria]]: 1 | + | *[[Habsburg Monarchy|Austria]]: November 1, 1781 (first step; second step: 1848) |

| − | *[[Bohemia]]: 1 | + | *[[Bohemia]]: November 1, 1781 (first step; second step: 1848) |

| − | *[[Baden]]: 23 | + | *[[Baden]]: July 23, 1783 |

| − | *[[Denmark]]: 20 | + | *[[Denmark]]: June 20, 1788 |

| − | *[[French First Republic|France]]: 3 | + | *[[French First Republic|France]]: November 3, 1789 |

| − | *[[Helvetic Republic]]: 4 | + | *[[Helvetic Republic]]: May 4, 1798 |

| − | *[[Schleswig-Holstein]]: 19 | + | *[[Schleswig-Holstein]]: December 19, 1804 |

| − | *[[Swedish Pomerania]]: 4 | + | *[[Swedish Pomerania]]: July 4, 1806 |

| − | *[[Duchy of Warsaw]] ([[Poland]]): 22 | + | *[[Duchy of Warsaw]] ([[Poland]]): July 22, 1807 |

| − | *[[Kingdom of Prussia|Prussia]]: 9 | + | *[[Kingdom of Prussia|Prussia]]: October 9, 1807 (effectively 1811-1823) |

*[[Mecklenburg]]: October 1807 (effectively 1820) | *[[Mecklenburg]]: October 1807 (effectively 1820) | ||

| − | *[[Bavaria]]: | + | *[[Bavaria]]: August 1808 |

| − | *[[Duchy of Nassau|Nassau]]: | + | *[[Duchy of Nassau|Nassau]]: September 1812 |

| − | *[[Estonia]]: | + | *[[Estonia]]: March 1816 |

| − | *[[Courland]]: | + | *[[Courland]]: August 1817 |

| + | *[[Württemberg]]: November 1817 | ||

{{col-break}} | {{col-break}} | ||

| − | + | *[[Livonia]]: March 26, 1819 | |

| − | *[[Livonia]]: 26 | ||

*[[Kingdom of Hanover|Hanover]]: 1831 | *[[Kingdom of Hanover|Hanover]]: 1831 | ||

| − | *[[Saxony]]: 17 | + | *[[Saxony]]: March 17, 1832 |

| − | *[[Kingdom of Hungary|Hungary]]: 11 | + | *[[Kingdom of Hungary|Hungary]]: April 11, 1848 (first time), March 2, 1853 (second time) |

| − | *[[Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg)|Croatia]]: 8 | + | *[[Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg)|Croatia]]: May 8, 1848 |

| − | *[[Austrian Empire]]: 7 | + | *[[Austrian Empire]]: September 7, 1848 |

*[[Principality of Bulgaria|Bulgaria]]: 1858 (de jure by [[Ottoman Empire]]; de facto in 1880) | *[[Principality of Bulgaria|Bulgaria]]: 1858 (de jure by [[Ottoman Empire]]; de facto in 1880) | ||

| − | *[[Russian Empire]]: 19 | + | *[[Russian Empire]]: February 19, 1861 |

*[[Tonga]]: 1862 | *[[Tonga]]: 1862 | ||

| − | *[[Congress Poland|Poland]]: 1864<ref>Gerhard Rempel, [http://mars.wnec.edu/~grempel/courses/russia/lectures/20emancipation.html Emancipation of the Serfs] Retrieved May 23, 2008.</ref> | + | *[[Congress Poland|Poland]]: 1864<ref>Gerhard Rempel, [http://mars.wnec.edu/~grempel/courses/russia/lectures/20emancipation.html Emancipation of the Serfs.] Retrieved May 23, 2008.</ref> |

*[[Georgia (country)|Georgia]]: 1864-1871 | *[[Georgia (country)|Georgia]]: 1864-1871 | ||

*[[Kalmykia]]: 1892 | *[[Kalmykia]]: 1892 | ||

| Line 198: | Line 152: | ||

*[[Afghanistan]]: 1923 | *[[Afghanistan]]: 1923 | ||

*[[England]]: ([[Copyhold]] tenure officially abolished 1925) | *[[England]]: ([[Copyhold]] tenure officially abolished 1925) | ||

| + | *[[China]]: 1949 (with the establishment of the [[People's Republic of China]]) | ||

*[[Bhutan]]: 1956 | *[[Bhutan]]: 1956 | ||

| − | *[[Tibet]]: | + | *[[Tibet]]: 1959 |

{{col-end}} | {{col-end}} | ||

| Line 206: | Line 161: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Bloch, Marc. ''Feudal Society, Volume 1: The Growth of Ties of Dependence.'' L. A. Manyon | + | * Backman, Clifford R. ''The Worlds of Medieval Europe''. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0195121698. |

| − | * Dhont, Jan | + | * Bloch, Marc. ''Feudal Society, Volume 1: The Growth of Ties of Dependence.'' Translated by L. A. Manyon. University Of Chicago Press, 1964. ISBN 978-0226059785. |

| − | + | * Bonnassie, Pierre. ''From Slavery to Feudalism in South-Western Europe''. Translated by Birrell Jean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521363242. | |

| − | * | + | * Coulborn, Rushton (ed.). ''Feudalism in History''. Princeton University Press, 1956. |

| − | + | * Dhont, Jan. ''La Alta Edad Media'' ''(Das früche Mittlelatter)''. Madrid: Siglo XXI. ISBN 8432300497. | |

| − | * Frantzen, Allen J., and Douglas Moffat | + | * Freedman, Paul, and Monique Bourin (eds.). ''Forms of Servitude in Northern and Central Europe. Decline, Resistance and Expansion''. Brepols Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-2503516943. |

| − | * | + | * Frantzen, Allen J., and Douglas Moffat (eds.). ''The World of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England''. Glasgow: Cruithne Press, 1994. ISBN 978-1873448038. |

| − | * Strayer, Joseph R. ''Western Europe in the Middle Ages''. Longman Higher Education | + | * Goldstein, Melvyn C. ''A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State.'' University of California Press, 1991. ISBN 0520075900. |

| − | * White, Stephen D. ''Re-Thinking Kinship and Feudalism in Early Medieval Europe'' | + | * Grunfeld, A. Tom. ''The Making of Modern Tibet.'' East Gate Book; Rev Sub edition, 1996. ISBN 978-1563247132. |

| + | * Strayer, Joseph R. ''Western Europe in the Middle Ages''. Longman Higher Education, 1982. ISBN 978-0673160522. | ||

| + | * Strong, Anna Louise. ''When Serfs Stood Up in Tibet''. Red Sun Publishers, 1976. ISBN 978-0918302007. | ||

| + | * White, Stephen D. ''Re-Thinking Kinship and Feudalism in Early Medieval Europe,'' 2nd edition. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Variorum, 2005. ISBN 978-0860789604. | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| + | All links retrieved January 26, 2023. | ||

| + | * [http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~atpc/heritage/history/h-life/peasant.html An extract from the book "Serfdom to Self-Government: Memoirs of a Polish Village Mayor, 1842–1927"] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Serfdom|212365176|Russian_serfdom|90041730|}} | {{Credits|Serfdom|212365176|Russian_serfdom|90041730|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 09:56, 26 January 2023

Serfdom is the socio-economic status of unfree peasants under feudalism, and specifically relates to Manorialism. Serfdom was the enforced labor of serfs on the fields of landowners, in return for their protection as well as the right to work on their leased fields. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe, evolving from agricultural slavery of the late Roman Empire, it flourished in Europe during the Middle Ages, lasting until the nineteenth century. Serfdom also appeared with feudalism in China, Japan, India, pre-Columbian Mexico, and elsewhere.

Serfdom involved work not only on fields, but various agriculture-related works, like forestry, mining, transportation (both land and river-based), crafts, and even in production. Manors formed the basic unit of society during this period, and both the lord and his serfs were bound legally, economically, and socially. Serfs were laborers who were bound to the land; they formed the lowest social class of the feudal society. Serfs were also defined as people in whose labor landowners held property rights.

After the Renaissance, serfdom became increasingly rare in most of Western Europe but grew strong in Central and Eastern Europe, where it had previously been less common. In England, it lasted legally up to the 1600s and in France until 1789. There were native-born Scottish serfs until 1799, when coal miners previously kept in serfdom gained emancipation. In Eastern Europe, the institution persisted until the mid-nineteenth century. It persisted in Austria-Hungary until 1848, and was abolished in Russia only in 1861. Tibet is believed to be the last place to have abolished serfdom, in 1959.

Although the end of serfdom means freedom, in many cases the transition to a new social order was far from smooth. Those in power often "freed" their serfs without concern for their well-being, caring only for their own situation. Merely breaking apart a system that has injustices and inequalities does not necessarily result in positive advances. The end of serfdom and all its problems is but one step toward the establishment of a harmonious and just society.

Etymology

The word serf originated from the Middle French "serf," and can be traced farther back to the Latin servus, meaning "slave." In Late Antiquity and most of the Middle Ages, what are now call serfs were usually designated in Latin as coloni (sing. colonus). As slavery gradually disappeared and the legal status of these servi became nearly identical to that of coloni, the term changed meaning into the modern concept of "serf." Serfdom is distinguished from slavery by rights the serfs held by a custom generally recognized as inviolable, by the social structure that made the peasants servile in a group rather than individually, and by the fact that they could usually pass the right to work their land on to a son.

The role of serfs

The essential characteristic of a manorial society was the near-total subordination of the peasants to the economic authority and jurisdiction of the landlord. However, not all peasants were completely subsumed under serfdom.

In medieval times, in England, vast amounts of land belonged to the Church; other land was owned privately. Indispensable for the survival of small landowners was the common land (Allmende in French), which was collective arable and forest land used for cultivation and for feeding livestock.

Landholders consisted of the nobility, the Church, and royalty. Serfs were allowed to work certain plots of land in exchange for a percentage of the product they produced. While most serfs were farmers, some were craftsmen, such as blacksmiths or millers. In most serfdoms, serfs were legally part of the land, and if the land was sold, they were sold with it. Medieval manors consisted of a manor house, where the landlord, knight, or baron lived, and a village consisting of peasant houses. These homes were actually one-bedroom huts made from wooden beams, mud, and straw. During the winter months, warmth was made by allowing the farm animals (goats, sheep, chickens, geese, and often cattle) to sleep inside.

The lives of serfs were very strenuous. The lord needed to maintain his authority in order to maintain the social structure. The priest was the bedrock of village life and all members of the community were dependent on him for their religious instruction and obligations. The priest could “proclaim [a serf’s duties], more for the society than for the ploughman; such total servitude is indeed useful to everyone.”[1] Lords and priests who were able to insist that the serf’s role was indeed essential and important to the survival of the community often perpetuated this system.

The serfs had a place in feudal society in much the same fashion as a baron or a knight. A serf's place was that, in return for protection, he would reside upon and work a parcel of land held by his lord. There was, thus, a degree of reciprocity in the manorial system. The period rationale was that a serf "worked for all," while a knight or baron "fought for all," and a churchman "prayed for all;" thus everyone had his place. The serf worked harder than the others, and was the worst fed and paid, but at least he had his place and, unlike in slavery, he had his own land and properties. A manorial lord could not sell his serfs as a Roman might sell his slaves. On the other hand, if he chose to dispose of a parcel of land, the serf or serfs associated with that land went with it to serve their new lord. Further, a serf could not abandon his lands without permission, nor could he sell them.

History

Social institutions similar to serfdom were known in ancient times. The status of the helots in the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta resembled that of the medieval serfs, as did the condition of the peasants working on government lands in ancient Rome. These Roman peasants, known as coloni, or "tenant farmers," are some of the possible precursors of the serfs. The Germanic tribes invading the Roman Empire for the most part displaced wealthy Romans as the landlords but left the economic system itself intact.

However, medieval serfdom really began with the breakup of the Carolingian Empire around the tenth century. The demise of this empire, which had ruled much of the western Europe for more than 200 years, was followed by a long period during which no strong central governments existed in most of Europe. During this period, powerful feudal lords encouraged the establishment of serfdom as a source of agricultural labor. Serfdom, indeed, was an institution that reflected a fairly common practice whereby great landlords were assured that others worked to feed them and were held down, legally and economically, while doing so. This arrangement provided most of the agricultural labor throughout the Middle Ages. Parts of Europe however, including much of Scandinavia, never adopted many feudal institutions, including serfdom.

In the later Middle Ages, serfdom began to disappear west of the Rhine even as it spread through Eastern Europe. This was one important cause for the deep differences between the societies and economies of Eastern and Western Europe. In Western Europe, the rise of powerful monarchs, towns, and an improving economy weakened the manorial system through the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and serfdom was rare following the Renaissance.

Serfdom in Western Europe came largely to an end in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, because of changes in the economy, population, and laws governing lord-tenant relations in Western European nations. The enclosure of manor fields for livestock grazing and for larger arable plots made the economy of serfs’ small strips of land in open fields less attractive to the landowners. Furthermore, the increasing use of money made tenant farming by serfs less profitable; for much less than it cost to support a serf, a lord could now hire workers who were more skilled and pay them in cash. Paid labor was also more flexible since workers could be hired only when they were needed.

At the same time, increasing unrest and uprisings by serfs and peasants, like Tyler’s Rebellion in England in 1381, put pressure on the nobility and the clergy to reform the system. As a result serf and peasant demands were accommodated to some extent by the gradual establishment of new forms of leasing the land and increased personal liberties. Another important factor in the decline of serfdom was industrial development—especially the Industrial Revolution. With the growing profitability of industry farmers wanted to move to towns to receive higher wages than those they could earn working in the fields, while landowners also invested in the more profitable industry. This also led to the growing process of urbanization.

Serfdom reached Eastern European countries relatively later than Western Europe—it became dominant around the fifteenth century. Before that time, Eastern Europe had been much less populated than Western Europe. Serfdom developed in Eastern Europe after the Black Death epidemics, which not only stopped the migration but depopulated Western Europe. The resulting large land-to-labor ratio combined with Eastern Europe's vast, sparsely populated areas gave the lords an incentive to bind the remaining peasantry to their land. With increased demand for agricultural products in Western Europe during the later era when Western Europe limited and eventually abolished serfdom, serfdom remained in force throughout Eastern Europe during the seventeenth century so that nobility-owned estates could produce more agricultural products (especially grain) for the profitable export market.

Such Eastern European countries include Prussia (Prussian Ordinances of 1525), Austria, Hungary (laws of late fifteenth, early sixteenth centuries), the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (szlachta privileges of early sixteenth century) and the Russian Empire (laws of late sixteenth/first half of seventeenth century). This also led to the slower industry development and urbanization of those regions. Generally, this process, referred to as "second serfdom" or "export-led serfdom," which persisted until the mid-nineteenth century, became very repressive and substantially limited serfs' rights.

In many of these countries, serfdom was abolished during the Napoleonic invasions of the early nineteenth century. Serfdom remained the practice on the most part of territory of Russia until February 19, 1861, though in Russian Baltic provinces it has been abolished in the beginning of nineteenth century (Russian Serfdom Reforms). Russian serfdom was perhaps the most notable among the Eastern European experiences, as it was never influenced by German law and migrations, and the serfdom and manorialism systems were forced by the crown (Tsar), not the nobility.

Beyond Europe, a number of other regions including much of Asia also established feudal societies, some of which incorporated serfdom although not uniformly. According to Joseph R. Strayer, feudalism was found in the societies of the Byzantine Empire, Iran, ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt (Sixth to Twelfth dynasty), Muslim India, China (Zhou Dynasty, end of Han Dynasty, Tibet (thirteenth century-1959), and Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), and in Japan during the Shogunate. Tibet is believed to be the last place to have abolished serfdom, in 1959.

The system of serfdom

A freeman became a serf usually through force or necessity. Sometimes freeholder or allodial owners were intimidated into dependency by the greater physical and legal force of a local baron. Often, a few years of crop failure, a war, or brigandage might leave a person unable to make his own way. In such a case a bargain was struck with the lord. In exchange for protection, service was required, in payment and/or with labor. These bargains were formalized in a ceremony known as "bondage," in which a serf placed his head in the seigneur's hands, parallel to the ceremony of "homage" where a vassal placed his hands between those of his lord. These oaths bonded the seigneur to their new serf and outlined the terms of their agreement.[2] Often these bargains were severe. A seventh century Anglo Saxon “Oath of Fealty" states

By the Lord before whom this sanctuary is holy, I will to N. be true and faithful, and love all which he loves and shun all which he shuns, according to the laws of God and the order of the world. Nor will I ever with will or action, through word or deed, do anything which is unpleasing to him, on condition that he will hold to me as I shall deserve it, and that he will perform everything as it was in our agreement when I submitted myself to him and chose his will.

To become a serf was a commitment that invaded all aspects of the serf’s life. Moreover, serfdom was inherited. By taking on the duties of serfdom, serfs bound not only themselves but all of their future heirs.

Classes

The class of peasant was often broken down into smaller categories. The distinctions between these classes were often less clear than would be suggested by the different names encountered for them. Most often, there were two types of peasants—freemen and villeins. However, both half-villeins, cottars or cottagers, and slaves made up a small percentage of workers.

Freemen

Freemen were essentially rent-paying tenant farmers who owed little or no service to the lord. In parts of eleventh-century England these freemen made up only ten percent of the peasant population and in the rest of Europe their numbers were relatively small.

Villeins

A villein was the most common type of serf in the Middle Ages. Villeins had more rights and status than those held as slaves, but were under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from the freeman. Villeins generally rented small homes, with or without land. As part of the contract with their landlord, they were expected to use some of their time to farm the lord's fields and the rest of their time was spent farming their own land. Like other types of serfs, they were required to provide other services, possibly in addition to a rent of money or goods. These services could be very onerous. Villeins were tied to the land and could not move away without their lord's consent. However, in other regards, they were free men in the eyes of the law. Villeins were generally able to have their own property, unlike slaves. Villeinage, as opposed to other forms of serfdom, was most common in Western European feudalism, where land ownership had developed from roots in Roman law.

A variety of kinds of villeinage existed in the European Middle Ages. Half-villeins received only half as many strips of land for their own use and owed a full complement of labor to the lord, often forcing them to rent out their services to other serfs to make up for this hardship. Villeinage was not, however, a purely exploitative relationship. In the Middle Ages, land guaranteed sustenance and survival, and being a villein guaranteed access to land. Landlords, even where legally able to, rarely evicted villeins because of the value of their labor. Villeinage was much preferable to being a vagabond, a slave, or an un-landed laborer.

In many medieval countries, a villein could gain freedom by escaping to a city and living there for more than a year; but this avenue involved the loss of land and agricultural livelihood, a prohibitive price unless the landlord was especially tyrannical or conditions in the village were unusually difficult. Villeins newly arrived in the city in some cases took to crime for survival, which gave the alternate spelling "villain" its modern meaning.

Cottagers

Cottars or cottagers, another type of serf, did not possess parcels of land to work. They spent all of their time working the lord’s fields. In return, they were given their hut, gardens, and a small portion of the lord’s harvest.

Slaves

The last type of serf was the slave. Slaves had the fewest rights and benefits from the manor and were also given the least. They owned no land, worked for the lord exclusively and survived on donations from the landlord. It was always in the interest of the lords to prove that a servile arrangement existed, as this provided them with greater rights to fees and taxes. The legal status of a man was a primary issue in many of the manorial court cases of the period.

Duties

The usual serf (not including slaves or cottars) paid his fees and taxes in the form of seasonally appropriate labor. Usually, a portion of the week was devoted to plowing his lord's fields (demesne), harvesting crops, digging ditches, repairing fences, and often working in the manor house. The lord’s demesne included more than just fields: It included all grazing rights, forest produce (nuts, fruits, timber, and forest animals), and fish from the stream; the lord had exclusive rights to these things. The rest of the serf’s time was devoted to tending his or her own fields, crops and animals in order to provide for his or her family. Most manorial work was segregated by gender during the regular times of the year; however, during the harvest, the whole family was expected to work the fields.

Corvée, or corvée labor, was a type of annual tax payable as labor to the monarch, vassal, overlord, or lord of the manor. It was used to complete royal projects, to maintain roads and other public facilities, and to provide labor to maintain the feudal estate.

The difficulty of a serf's life derived from the fact that his work for his lord coincided with, and took precedence over, the work he had to perform on his own lands: When the lord's crops were ready to be harvested, so were his own. On the other hand, the serf could look forward to being well fed during his service; it was a poor lord who did not provide a substantial meal for his serfs during the harvest and planting times. In exchange for this work on the lord's property, the serf had certain privileges and rights. They were allowed to gather deadwood from their lord’s forests. For a fee, the serfs were allowed to use the manor’s mills and ovens.

In addition to service, a serf was required to pay certain taxes and fees. Taxes were based on the assessed value of his lands and holdings. Fees were usually paid in the form of foodstuffs rather than cash. The best ration of wheat from the serf’s harvest always went to the landlord. For the most part, hunting on the lord’s property was prohibited for the serfs. On Easter Sunday the peasant family owed an extra dozen eggs, and on Christmas a goose was expected as well. When a family member died, extra taxes were paid to the manor for the cost of that individual's labor. Any young woman who wished to marry a serf outside of her manor was forced to pay a fee for the lost labor. It was also a matter of discussion whether serfs could be required by law in times of war or conflict to fight for their lord's land and property.

The restraints of serfdom on personal and economic choice were enforced through various forms of manorial common law and the manorial administration and court.

Benefits

Within his constraints, a serf had some freedom. Though the common wisdom is that a serf owned "only his belly"—even his clothes were the property, in law, of his lord—a serf might still accumulate personal property and wealth, and some serfs became wealthier than their free neighbors, although this was rather an exception to the general rule. A well-to-do serf might even be able to buy his freedom.

Serfs could raise what they saw fit on their lands (within reason—a serf's taxes often had to be paid in wheat, a notoriously difficult crop), and sell the surplus at market. Their heirs were usually guaranteed an inheritance.

The landlord could not dispossess his serfs without cause and was supposed to protect them from the depredations of outlaws or other lords, and he was expected to support them by charity in times of famine.

Variations

Specifics of serfdom varied greatly through time and region. In some places, serfdom was merged with or exchanged for various forms of taxation.

The amount of labor required varied. In Poland, for example, it was few days a year in the thirteenth century; one day per week in the fourteenth century; four days per week in the seventeenth century and six days per week in the eighteenth century. Early serfdom in Poland was most limited on the royal territories (królewszczyzny).

Sometimes, serfs served as soldiers in the event of conflict and could earn freedom or even ennoblement for valor in combat. In other cases, serfs could purchase their freedom, be manumitted by their enlightened or generous owners, or flee to towns or newly-settled land where few questions were asked. Laws varied from country to country: In England, a serf who made his way to a chartered town and evaded recapture for a year and a day obtained his freedom.

In Russia, the legal code of Ivan III of Russia, Sudebnik (1497), restricted the mobility of peasants. Their right to leave their master was limited to a period of one week before and after the so-called Yuri's Day (November 26). A temporary (Заповедные лета, or Prohibition years) and later an open-ended prohibition for peasants to leave their masters was introduced by the ukase of 1597, which also defined the so-called fixed years (Урочные лета, or urochniye leta), or the five-year time frame for search of the runaway peasants. This was later extended to ten years.

In Tibet, the greater part of the rural population—some 700,000 of an estimated total population of 1,250,000—were serfs as late as 1953. Tied to the land under an essentially feudal system, they were allotted only a small parcel to grow their own food, spending most of their time laboring for the monasteries and individual high-ranking lamas, or for a secular aristocracy. However, Goldstein has noted that not all serfs were destitute, some could amass considerable wealth and even own their own land.[3] There were several types of serf sub-status of which one of the most important was the "human lease" which enabled a serf to acquire a degree of personal freedom because, despite retaining the concept of lordship, the serfs were not bound to a landed estate.[4] After China took over Tibet and the Dalai Lama fled to India, the communist government started to abandon serfdom, allowing serfs to grow their own crops and vegetables, albeit under the communist system.[5]

The decline of serfdom

Serfdom became progressively less common through the Middle Ages, particularly after the Black Death reduced the rural population and increased the bargaining power of workers. Furthermore, the lords of many manors were willing (for payment) to manumit ("release") their serfs.

Serfdom had largely died out in England, by 1500, as a personal status, but land held by serf tenure (unless enfranchised) continued to be held by what was henceforth known as a copyhold tenancy, which was not abolished until 1925. During the Late Middle Ages, peasant unrest led to outbreaks of violence against landlords. In May 1381, the English peasants revolted because of the heavy tax placed upon them by Parliament. There were similar occurrences at around the same time in Castille, Germany, northern France, Portugal, and Sweden. Although these peasant revolts were often successful, it usually took a long time before legal systems were changed. In France, this occurred on August 11, 1789, with the “Decree Abolishing the Feudal System.” This decree abolished the manorial system completely.

The beginning of the eradication of the feudal system marks an era of rapid change in Europe. Taxes levied by the state took the place of labor dues levied by the lord. The change in status following the enclosure movements beginning in the later eighteenth century, in which various lords abandoned the open field farming of previous centuries in exchange for, essentially, taking all the best land for themselves and "freeing" their serfs, may well have made serfdom a lifestyle desperately to be wished for by many peasant families.

Although serfdom began its decline in Europe in the Middle Ages, it took many hundreds of years to disappear completely. In addition, the struggles of the working class during the Industrial Revolution has been compared with the struggles of the serfs during the Middle Ages. Serfdom is an institution that has been commonplace in human history; however, it has not always been of the same nature. In parts of the world today, forced labor is still used.

Emancipation from serfdom was achieved in various countries on the following dates:

|

|

Notes

- ↑ Allen J. Frantzen and Douglas Moffat (eds.), The World of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England (Glasgow: Cruithne Press, 1994), p. 60.

- ↑ Marc Bloch, Feudal Society, Volume 1: The Growth of Ties of Dependence (University Of Chicago Press, 1964, ISBN 978-0226059785).

- ↑ Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State (University of California Press, 1991, ISBN 0520075900), p. 5.

- ↑ Melvyn C. Goldstein, "Serfdom and mobility: an examination of the institution of 'human lease' in traditional Tibetan society" Journal of Asian Studies 30, (3) (May 1971): 521-534.

- ↑ Anna Louise Strong, When Serfs Stood Up in Tibet, p. 265.

- ↑ Gerhard Rempel, Emancipation of the Serfs. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Backman, Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0195121698.

- Bloch, Marc. Feudal Society, Volume 1: The Growth of Ties of Dependence. Translated by L. A. Manyon. University Of Chicago Press, 1964. ISBN 978-0226059785.

- Bonnassie, Pierre. From Slavery to Feudalism in South-Western Europe. Translated by Birrell Jean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521363242.

- Coulborn, Rushton (ed.). Feudalism in History. Princeton University Press, 1956.

- Dhont, Jan. La Alta Edad Media (Das früche Mittlelatter). Madrid: Siglo XXI. ISBN 8432300497.

- Freedman, Paul, and Monique Bourin (eds.). Forms of Servitude in Northern and Central Europe. Decline, Resistance and Expansion. Brepols Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-2503516943.

- Frantzen, Allen J., and Douglas Moffat (eds.). The World of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labor in Medieval England. Glasgow: Cruithne Press, 1994. ISBN 978-1873448038.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press, 1991. ISBN 0520075900.

- Grunfeld, A. Tom. The Making of Modern Tibet. East Gate Book; Rev Sub edition, 1996. ISBN 978-1563247132.

- Strayer, Joseph R. Western Europe in the Middle Ages. Longman Higher Education, 1982. ISBN 978-0673160522.

- Strong, Anna Louise. When Serfs Stood Up in Tibet. Red Sun Publishers, 1976. ISBN 978-0918302007.

- White, Stephen D. Re-Thinking Kinship and Feudalism in Early Medieval Europe, 2nd edition. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Variorum, 2005. ISBN 978-0860789604.

External links

All links retrieved January 26, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.