Bhutan

| ' Druk Gyal-khab<br\>Brug Rgyal-khab<br\>Dru Gäkhap Kingdom of Bhutan | |||||

| |||||

| Motto: "One Nation, One People" | |||||

| Anthem: Druk tsendhen | |||||

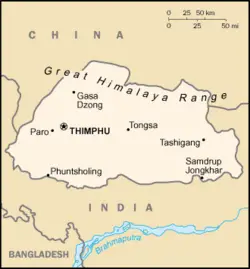

| Capital | Thimphu | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official languages | Dzongkha | ||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary democracy and Constitutional monarchy | ||||

| Â - King | Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck | ||||

| Â - Prime Minister | Jigme Y. Thinley | ||||

| Formation | Early 17th century | ||||

| Â - Wangchuk Dynasty | 17 December 1907Â | ||||

| Â - Constitutional Monarchy | 2007Â | ||||

| Area | |||||

|  - Total | 38,816 km² (134th) 14987 sq mi | ||||

| Â - Water (%) | 1.1 | ||||

| Population | |||||

| Â - 2009 estimate | 691,141 | ||||

| Â - 2005 census | 634,982 | ||||

|  - Density | 18.1/km² 47/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate | ||||

| Â - Total | $3.875 billion | ||||

| Â - Per capita | $5,429 | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate | ||||

| Â - Total | $1.412 billion | ||||

| Â - Per capita | $1,978 | ||||

| HDIÂ Â (2007) | |||||

| Currency | Ngultrum2 (BTN)

| ||||

| Time zone | BTT (UTC+6:00) | ||||

|  - Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+6:00) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .bt | ||||

| Calling code | +975 | ||||

The Kingdom of Bhutan is a landlocked South Asian nation situated between India and China. A strategic location, it controls several key Himalayan mountain passes.

One of the most isolated nations in the world, Bhutan is often described as the last surviving refuge of traditional Himalayan Buddhist culture. The government tightly controls foreign influences and tourism to preserve its traditional culture.

Bhutan is linked historically and culturally with its northern neighbor Tibet, yet politically and economically today's kingdom has drawn much closer to India.

Because of the serenity and the virginity of the country and its landscapes, Bhutan today is sometimes referred to as the Last Shangri-La.

Bhutan is a country where gross national happiness is more important than gross national product.

Geography

The word âBhutanâ may be derived from the Sanskrit word âBhu-Uttanâ which means âhigh land,â or âBhots-ant,â which means âsouth of Tibet.â The Dzongkha (and Tibetan) name for the country is âDruk Yulâ (Land of the Thunder Dragon).

The land area is 18,147 square miles (47,000 square kilometres) or about half the size of the U.S. state of Indiana. Its shape, area, and mountainous location are comparable to that of Switzerland.

The entire country is mountainous except for a small strip of subtropical plains in the extreme south that is intersected by valleys known as the Duars. The northern region consists of an arc of glaciated mountain peaks with an extremely cold climate. The elevation gain from the plains to the glacier-covered Himalayan heights exceeds 23,000 feet (7000 meters).

The lowest point is Drangme Chhu at 318 feet (97 meters). The highest point is claimed to be the Kula Kangri, at 24,780 feet (7553 meters), but detailed topographic studies claim Kula Kangri is in Tibet and modern Chinese measurements claim that Gangkhar Puensum, which has the distinction of being the highest unclimbed mountain in the world, is higher at 24,835 feet (7570 meters).

The Black Mountains in central Bhutan form a watershed between two river systems: the Mo Chhu and the Drangme Chhu. Fast-flowing rivers have carved out deep gorges in the lower mountain areas. The Torsa, Raidak, Sankosh, and Manas are the main rivers. The rivers (excepting the Manas and Lhobhrak) flow from the Great Himalayas through narrow valleys, emerging into the Duar and eventually draining into the Brahmaputra River.

Watered by snow-fed rivers, alpine valleys provide pasture for livestock, tended by a sparse population of migratory shepherds. Woodlands of the central region provide most of Bhutan's forest production. The country had a forest cover of 64 percent as of October 2005.

In the south are the Shiwalik Hills, covered with dense, deciduous forests, alluvial lowland river valleys, and mountains up to around 4900 feet (1500 meters). The foothills descend into the subtropical Duars plain, most of which is in India. The six-mile (10km) wide strip that comprises the Bhutan Duars is divided into two partsânorthern and southern. The northern Duars, which abuts the Himalayan foothills, has rugged, sloping terrain and dry, porous soil with dense vegetation and abundant wildlife. The southern Duars have moderately fertile soil, heavy savannah grass, dense, mixed jungle, and freshwater springs.

Climate

The climate varies with altitude, from subtropical in the south to temperate in the highlands and a polar-type climate, with year-round snow, in the north. There are five distinct seasons: summer, monsoon, autumn, winter and spring. Western Bhutan has the heavier monsoon rains; southern Bhutan has hot humid summers and cool winters; central and eastern Bhutan is temperate and drier than the west with warm summers and cool winters.

Temperatures vary according to elevation. Temperatures in Thimphu, located at 7217 feet (2200 meters), range from approximately 60°F to 79°F (15°C to 26°C) during the monsoon season of June through September but drop to between about 25°F to 61°F (-4°C and 16°C) in January.

Annual precipitation ranges widely. In the severe climate of the north, there is only about 1.5 inches (40mm) of annual precipitationâprimarily snow. In the temperate central regions, a yearly average of around 40 inches (1000mm) is more common, and 307 inches (7800mm) per year has been registered at some locations in the humid, subtropical south, ensuring the thick tropical forest, or savanna.

Resources

Centuries of isolation, a small population, and topographical extremes have lead to Bhutan maintaining one of the most intact ecosystems in the world. Over fifty-five hundred varieties of plant life exist, including around 300 medicinal plants. A total of 165 species are known to exist, including many rare and endangered species like the red panda, snow leopard, and golden langur.

Natural resources include timber, hydropower, gypsum, and calcium carbonate.

Natural hazards include violent storms from the Himalayas, which are the source of one of the country's namesâthe Land of the Thunder Dragon. There are frequent landslides during the rainy season.

Most of the population lives in the central highlands. Thimphu is the capital and largest city, which has a population of 50,000. Jakar, the administrative headquarters of Bumthang District, is the place where Buddhism entered Bhutan. Bumthang is the spiritual region and has a number of monasteries and places of religious pilgrimage, as well as numerous religious legends associated with it. Other cities include Mongar, Paro (the site of the international airport), Punakha (the old capital), Phuentsholing (the commercial hub), Samdrup Jongkhar, Trashigang, and Trongsa.

History

Stone tools, weapons, and remnants of large stone structures provide evidence that Bhutan was inhabited as early as 2000 B.C.E. The Bhutanese believe the Lhopu (a small tribe in southwest Bhutan who speak a Tibeto-Burman language) to be the aboriginal inhabitants. They were displaced by the arrival of Tibetans of Mongolian descent. Historians have theorized that the state of Lhomon may have existed between 500 B.C.E. and 600 C.E. The names Lhomon Tsendenjong (Sandalwood Country), and Lhomon Khashi, or Southern Mon (country of four approaches) have been found in ancient Bhutanese and Tibetan chronicles.

The earliest transcribed event in Bhutan was the passage of the Buddhist saint Padmasambhava (also called Guru Rinpoche) in the eighth century. Bhutan's early history is unclear, because most records were destroyed after fire ravaged Punakha, the ancient capital in 1827.

Padmasambhava is usually credited with bringing Tantric Buddhism to Bhutan, but two sites representing an earlier influence predate him. Kyichu in Paro District and Jambey in Bumthang District were built in 659 C.E., a century or so before Guru Rinpoche's arrival, by the quasi-legendary King of Tibet Songtsen Gampo.

By the tenth century, Bhutan's political development was heavily influenced by its religious history. Sub-sects of Buddhism emerged which were patronized by the various Mongol and Tibetan overlords. After Mongols declined in the fourteenth century, these sub-sects vied for supremacy, eventually leading to the ascendancy of the Drukpa sub-sect by the sixteenth century.

Until the early seventeenth century, Bhutan existed as a patchwork of minor warring fiefdoms until unified by the Tibetan lama and military leader Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal. To defend against intermittent Tibetan forays, Namgyal built a network of impregnable dzong (fortresses), and promulgated a code of law that helped to bring local lords under centralized control. Many such dzong still exist. After Namgyal's death in 1651, Bhutan fell into anarchy. The Tibetans attacked in 1710, and again in 1730 with the help of the Mongols. Both assaults were successfully thwarted, and an armistice was signed in 1759.

In the eighteenth century, the Bhutanese invaded and occupied the kingdom of Cooch Behar to the south. In 1772, Cooch Behar sought help from the British East India Company to oust the Bhutanese. A peace treaty was signed in which Bhutan agreed to retreat to its pre-1730 borders. However, the peace was tenuous, and border skirmishes with the British were to continue for the next hundred years, leading to the Duar War (1864 to 1865), a confrontation over who would control the Bengal Duars. Bhutan lost, and the Treaty of Sinchula between British India and Bhutan was signed, and the Duars were ceded to the United Kingdom in exchange for a rent of Rs. 50,000.

During the 1870s, power struggles between the rival valleys of Paro and Trongsa led to civil war. Ugyen Wangchuck, the ponlop (governor) of Trongsa, gained dominance, and, after civil wars and rebellions from 1882 to 1885, united the country. In 1907, an assembly of leading Buddhist monks, government officials, and heads of important families chose Ugyen Wangchuck as the hereditary king. In 1910 Bhutan signed a treaty that let Great Britain âguideâ Bhutan's foreign affairs.

India gained independence from the United Kingdom on August 15, 1947. Bhutan signed a treaty with India on August 8, 1949.

After the Chinese People's Liberation Army entered Tibet in 1951, Bhutan sealed its northern frontier and improved bilateral ties with India. To reduce the risk of Chinese encroachment, Bhutan began a modernization program that was largely sponsored by India.

In 1953, King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck established the country's legislature â a 130-member national assembly. In 1965, he set up a Royal Advisory Council, and in 1968 he formed a cabinet. In 1971, Bhutan was admitted to the United Nations, having held observer status for three years. In July 1972, Jigme Singye Wangchuck ascended to the throne at the age of 16 after the death of his father, Dorji Wangchuck.

Since 1988, Nepalese immigrants have accused the Bhutanese government of atrocities. These allegations remain unproven and are denied by Bhutan. Nepalese refugees have settled in U.N.-run camps in south-eastern Nepal where they have remained for 15 years.

In 1998, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck transferred most of his powers to the prime minister and allowed for impeachment of the king by a two-thirds majority of the national assembly. In 1999, the king lifted a ban on television and the internet, making Bhutan one of the last countries to introduce television. In his speech, he said that television was a critical step to the modernization of Bhutan as well as a major contributor to the country's gross national happiness (Bhutan is the only country to measure happiness). He warned that the misuse of television may erode traditional Bhutanese values.

Several guerrilla groups seeking to establish an independent Assamese state in northeast India set up guerilla bases in the forests of southern Bhutan from which they launched cross-border attacks on targets in Assam. Negotiations aimed at removing them peacefully failed. By December of 2003, the Royal Bhutan Army attacked the camps, co-operating with Indian armed forces. By January, 2003, the guerillas had been routed.

On November 13, 2005, Chinese soldiers crossed into Bhutan under the pretext that bad weather had forced them from the Himalayas. The Bhutanese government allowed this incursion on humanitarian grounds. Soon after, the Chinese began building roads and bridges within Bhutanese territory. The Bhutanese Foreign Minister took up the matter with Chinese authorities. In response, the Chinese Foreign Ministry stated that the border remains in dispute.

A new constitution was presented in early 2005. In December of that year Jigme Singye Wangchuck announced that he would abdicate in 2008. On December 14, 2006, he announced his immediate abdication. His son, Jigme Khesar Namgyal Wangchuck, took the throne.

Politics and government

Politics of Bhutan takes place in the framework of an absolute monarchy developing into a constitutional monarchy. The country has no written constitution or bill of rights. In 2001, the king commissioned the drafting of a constitution, and in March 2005 publicly unveiled it. In early 2007 it was awaiting a national referendum.

The King of Bhutan is head of state. In 1999, the king created a 10-member body called the Lhengye Zhungtshog (Council of Ministers). The king nominates members, who are approved by the National Assembly and serve fixed, five-year terms. Executive power is exercised by the Lhengye Zhungtshog.

Legislative power is vested in both the government and the national assembly. The unicameral national assembly, or Tshogdu, comprises 150 seats, 105 of which are elected from village constituencies, 10 represent religious bodies, and 35 are designated by the king to represent government and other secular interests. Members serve three-year terms. Elections were held in August 2005, and the next to be held in 2008. As the country prepared to introduce parliamentary democracy in 2008, political parties were legalized.

The chief justice is the administrative head of the judiciary. The legal system is based on Indian law and English common law. Bhutan has not accepted compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction. Local headmen and magistrates are the first to hear cases. Appeals may be made to an eight-member High Court, appointed by the king. A final appeal may be made to the king. Criminal matters and most civil matters are resolved by application of a seventeenth century legal code as revised in 1965. Traditional Buddhist or Hindu law controls family law issues. Criminal defendants have no right to a court-appointed attorney or jury trial. Detainees must be brought before a court within 24 hours of arrest.

For administrative purposes, Bhutan is divided into four "dzongdey" (administrative zones). Each dzongdey is further divided into "dzongkhag" (districts). There are 20 dzongkhag in Bhutan. Large dzongkhags are further divided into sub-districts known as "dungkhag." At the basic level, groups of villages form a constituency called "gewog" and are administered by a "gup," who is elected by the people.

The Royal Bhutan Army includes the Royal Bodyguard and the Royal Bhutan Police. Membership is voluntary, and the minimum age for recruitment is 18. The standing army numbers about 6000 and is trained by the Indian Army. It has an annual budget of about US$13.7-million, or 1.8 percent of GDP.

Bhutan handles most of its foreign affairs including the sensitive (to India) border demarcation issue with China. Bhutan has diplomatic relations with 22 countries, including the European Union, with missions in India, Bangladesh, Thailand and Kuwait. It has two UN missions, one in New York and one in Geneva. Only India and Bangladesh have residential embassies in Bhutan, while Thailand has a consulate office in Bhutan.

Indian and Bhutanese citizens may travel to each other's countries without a passport or visa using their national identity cards instead. Bhutanese citizens may work in India. Bhutan does not have formal diplomatic ties with its northern neighbor, China, although diplomatic exchanges have significantly increased. The first bilateral agreement between China and Bhutan was signed in 1998, and Bhutan has set up consulates in Macau and Hong Kong. Bhutanâs border with China is largely not demarcated and thus disputed in some places.

Economy

Bhutan is a country where âgross national happiness is more important than gross national product," the King of Bhutan said in 1987, in a response to accusations by a British journalist, that the pace of development in Bhutan was slow. This statement appears to have presaged findings by western economic psychologists, that questions the link between levels of income and happiness. The king was committed to building an economy appropriate for Bhutan's unique culture, based on Buddhist spiritual values, and has served as a unifying vision for the economy. A 2006 survey organized by the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom, ranked Bhutan as the planet's eighth happiest place.

Bhutan's economy is one of the world's smallest and least-developed, and is based on agriculture, forestry, and the sale of hydroelectric power to India. Agriculture provides the main livelihood for more than 80 percent of the population. Agrarian practices consist largely of subsistence farming and animal husbandry. Agricultural produce includes rice, chillis, dairy (yak) products, buckwheat, barley, root crops, apples, and citrus and maize at lower elevations.

The industrial sector is minimal. Industries include cement, wood products, processed fruits, alcoholic beverages and processing calcium carbide (a source of acetylene gas). Handicrafts, particularly weaving and the manufacture of religious art for home altars are a small cottage industry and a source of income for some.

A landscape that varies from hilly to ruggedly mountainous has made the building of roads and other infrastructure difficult and expensive. Most development projects, such as road construction, rely on Indian contract labor. This, and a lack of access to the sea, has meant that Bhutan has never been able to benefit from trading its produce.

Bhutan does not have a railway system, though Indian Railways plans to link up southern Bhutan with its vast network under an agreement signed in January 2005. The historic trade routes over the high Himalayas, which connected India to Tibet, have been closed since the 1959 military takeover of Tibet (although smuggling activity still brings Chinese goods into Bhutan).

Bhutan's currency, the ngultrum, is pegged to the Indian Rupee, which is accepted as legal tender. Incomes of over 100,000 ngultrum per annum are taxed, but few wage and salary earners qualify. Bhutan's inflation rate was estimated at about three percent in 2003.

Bhutan has a gross domestic product of around US$2.913-billion (adjusted to purchasing power parity), making it the 175th largest economy on the world list of 218 countries. Per capita income is around $3921, ranked 117th on a list of 181 countries. Government revenues total $146-million, although expenditures amount to $152-million. Sixty percent of the budget expenditure, however, is financed by India's Ministry of External Affairs.

Exports totalled $154-million in 2000. Export commodities included electricity (to India), cardamom, gypsum, timber, handicrafts, cement, fruit, precious stones, and spices. Export partners were [Japan]] 32.3 percent, Germany 13.2 percent, France 13.1 percent, South Korea 7.6 percent, United States 7.5 percent, Thailand 5.6 percent, and Italy 5 percent.

Imports totalled $196-million. Import commodities included fuel and lubricants, grain, aircraft, machinery and parts, vehicles, fabrics, and rice. Import partners were Hong Kong 66.6 percent, Mexico 20.2 percent, and France 3.8 percent.

Although Bhutan's economy is one of the world's smallest, it has grown rapidly with about 8 percent growth in 2005 and 14 percent in 2006.

Demographics

An extensive census conducted in April 2006 resulted in a population figure of 672,425. The population of Bhutan, once estimated at several million, was downgraded to 750,000, after a census in the early nineties. One view is that the numbers were inflated in the 1970s because of a perception that nations with populations of less than a million would not be admitted to the United Nations.

The population density, 117 per square mile, makes Bhutan one of the least densely populated countries in Asia. Roughly 20 percent live in urban areas composed of small towns mainly along the central valley and the southern border. This percentage is increasing rapidly as the pace of rural to urban migration has been picking up. The country has a median age of 20.4 years, and a life expectancy of 62.2 years.

Ethnicity

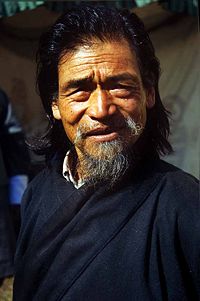

Bhutanese are physically similar to the Tibetans. The dominant ethnic group are the Ngalops, a Buddhist group based in the western part of the country. Their culture is closely related to that of Tibet. Much the same could be said of the Sharchops ("Easterners"), who are associated with the eastern part of Bhutan (but who traditionally follow the Nyingmapa rather than the official Drukpa Kagyu form of Tibetan Buddhism). These two groups together are called Bhutanese. The remaining 15 percent of the population is ethnic Nepali, most of whom are Hindu.

Bhutan has no caste system. Minority Hindus of Nepalese origin are discriminated against. Thousands of Nepalese were deported in the late 1980s, and others fled. The government has sought to assimilate the remaining Nepalese.

Religion

Mahayana Buddhism is the state religion, and Buddhists comprised about 90 percent of the population. Although originating from Tibetan Buddhism, the Bhutanese variety differs significantly in its rituals, liturgy, and monastic organization. The government gives annual subsidies to monasteries, shrines, monks, and nuns. Jigme Dorji Wangchuck's reign funded the manufacture of 10,000 gilded bronze images of the Buddha, publication of elegant calligraphied editions of the 108-volume Kangyur (Collection of the Words of the Buddha) and the 225-volume Tengyur (Collection of Commentaries), and the construction of numerous "chorten" (stupas) throughout the country. Guaranteed representation in the National Assembly and the Royal Advisory Council, Buddhists constitute the majority of society and are assured an influential voice in public policy.

There are 10,000 Buddhist monks who visit households and perform rites for birth, marriage, sickness, and death. A number of annual festivals, many featuring symbolic dances, highlight events in the life of Buddha. Both Buddhists and Hindus believe in reincarnation and the law of karma, which holds an individual's actions can influence his or her transmigration into the next life.

Eight percent of the population follows Indian and Nepalese-influenced Hinduism, while two percent are Muslim.

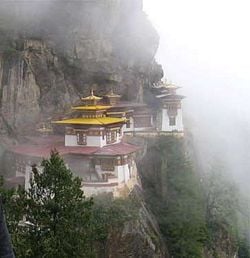

Monasteries

Monks join the monastery at six to nine years of age and are immediately placed under the discipleship of a headmaster. They learn to read "chhokey," the language of the ancient sacred texts, as well as Dzongkha and English. Trainee monks choose between two paths: to study theology and Buddhist theory, or becoming proficient in the rituals and personal practices of the faith.

The daily life of the monk is austere, particularly if they are stationed at one of the monasteries located high in the mountains. At these monasteries food is often scarce and must be carried up by the monks or their visitors. The monks are poorly clothed for winter conditions and the monasteries are unheated. The hardship of such a posting is well-recognizedâto have a son or brother serving in such a monastery is recognized as very good karma for the family.

A monk's spiritual training continues throughout his life. In addition to serving the community in sacramental roles, he may undertake several extended silent retreats. A common length for such a retreat is three years, three months, three weeks and three days. During the retreat time he will periodically meet with his spiritual master who will test him on his development to ensure that the retreat time is not being wasted.

Each monastery is headed by an abbot who is typically a lama, although the titles are distinct. The highest monk in the land is the chief abbot of Bhutan, whose title is Je Khenpo. He is theoretically equivalent in stature to the king.

The Central Monk Body is an assembly of 600 or so monks who attend to the most critical religious duties of the country. In the summer they are housed in Thimphu, the nation's capital, and in the winter they descend to Punakha dzong, the most sacred dzong in Bhutan, where Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal's mortal body has been kept under vigil since the late 1600s.

Men and women

Bhutanese women have traditionally had more rights than women in surrounding cultures, the most prominent being the right of land ownership. The property of each extended Bhutanese family is controlled by an "anchor mother" who is assisted by the other women of the family in running affairs. As she becomes unable to manage the property, the position of anchor mother passes on to a sister, daughter or niece. This pattern of inheritance is known as matrilinearity.

Men and women work together in the fields, and both may own small shops or businesses. Men take full part in household management, often cook, and are traditionally the makers and repairers of clothing (but do not weave the fabric). In the towns, a more "western" pattern of family structure is beginning to emerge, with the husband as breadwinner and the wife as home-maker. Both genders may be monks, although in practice the number of female monks is relatively small.

Land is divided equally between sons and daughters. Girls receive nearly equal educational opportunities, are accorded a lower status than boys, but are valued because they care for parents in old age.

Marriages are at the will of either party and divorce is not uncommon. Most are performed by a religious leader. The marriage ceremony consists of an exchange of white scarves and the sharing of a cup. Dowry is not practiced. Marriages can be officially registered when the couple has lived together for more than six months. Traditionally the groom moves to the bride's family home (matrilocality), but newlyweds may decide to live with either family depending on which household is most in need of labor. The Bhutanese are [Monogamy|monogamous]], polyandry (multiple husbands) has been abolished, but polygamy (multiple wives) is legal provided the first wife grants consent.

A highly refined system of etiquette, called "driglam namzha," supports respect for authority, devotion to the institution of marriage and family, and dedication to civic duty. It governs how to send and receive gifts, how to speak to those in authority, how to serve and eat food at public occasions, and how to dress. Men and women mix and converse freely, without the restrictions that separate the sexes elsewhere in South Asia.

Language

The national language is Dzongkha, one of 53 languages in the Tibetan language family. English has official status. Bhutanese monks read and write chhokey. The government classifies 19 related Tibetan languages as dialects of Dzongkha. Lepcha is spoken in parts of western Bhutan; Tshangla, a close relative of Dzongkha, is widely spoken in the eastern parts. Khengkha is spoken in central Bhutan. The Nepali language, an Indo-Aryan language, is widely spoken in the south. In schools, English is the medium of instruction and Dzongkha is taught as the national language. The languages of Bhutan have not been extensively studied.

Culture

Bhutan has relied on its geographic isolation to preserve many aspects of a culture that dates back to the mid-seventeenth century. Only in the last decades of the twentieth century were foreigners allowed to visit, and only then in limited numbers.

Food

Rice, and increasingly maize, are the staple foods of the country. Northern Indian cuisine is often mixed with the chillis of the Tibetan area in daily dishes. The diet in the hills is rich in protein because of the consumption of poultry, yak and beef. Soups of meat, rice, and dried vegetables spiced with chillis and cheese are a favorite meal during the cold seasons. Dairy foods, particularly butter and cheese from yaks and cows, are also popular, and indeed almost all milk is turned to butter and cheese. Popular beverages include butter tea, tea, locally brewed rice wine and beer. Bhutan is the only country to have banned smoking and the sale of tobacco.

Clothing

All Bhutanese citizens are required to observe the national dress code, known as "Driglam Namzha," while in public during daylight hours. Men wear a heavy knee-length robe tied with a belt, called a "gho," folded in such a way to form a pocket in front of the stomach. Women wear colorful blouses over which they fold and clasp a large rectangular cloth called a "kira," thereby creating an ankle-length dress. A short silk jacket, or "toego" may be worn over the "kira." Everyday gho and kira are cotton or wool, according to the season, patterned in simple checks and stripes in earth tones. For special occasions and festivals, colorfully patterned silk kira and, more rarely, gho may be worn.

When visiting a temple, or when appearing before a high level official, male commoners wear a white sash ("kabney") from left shoulder to opposite hip. Local and regional elected officials, government ministers, cabinet members, and the king himself each wear their own colored kabney. Women wear a narrow embroidered cloth draped over the left shoulder, a "rachu."

The dress code has met with some resistance from the ethnic Nepalese citizens living along the Indian border who resent having to wear a cultural dress which is not their own.

Architecture

Rural residents, who make up the majority of Bhutanâs population, live in houses built to withstand the long, cold winters, with wood-burning stoves for heat and cooking. These houses have some land for growing vegetables.

Each valley or district is dominated by a huge "dzong," or high-walled fortress, which serves the religious and administrative center of the district.

Religious monuments, prayer walls, prayer flags, and sacred mantras carved in stone hillsides are prevalent. Among the religious monuments are âchorten,â the Bhutanese version of the Indian stupa. They range from simple rectangular "house" chorten to complex edifices with ornate steps, doors, domes, and spires. Some are decorated with the Buddha's eyes that see in all directions simultaneously. These earth, brick, or stone structures commemorate deceased kings, Buddhist saints, venerable monks, and other notables, and sometimes they serve as reliquaries.

Prayer walls are made of laid or piled stone and inscribed with Tantric prayers. Prayers printed with woodblocks on cloth are made into tall, narrow, colorful prayer flags, which are then mounted on long poles and placed both at holy sites and at dangerous locations to ward off demons and to benefit the spirits of the dead. To help propagate the faith, itinerant monks travel from village to village carrying portable shrines with many small doors, which open to reveal statues and images of the Buddha, bodhisattavas, and notable lamas.

Education

Monasteries provided education before a modern education system was introduced in the 1960s. More children attend school, but over 50 percent still do not attend. Education is not compulsory. There are seven years of primary schooling then four years of secondary school. In 1994, primary schools enrolled 60,089 pupils. In that year, secondary schools enrolled 7299 students. Bhutan has one college, affiliated to the University of Delhi. The literacy rate was only 42.2 percent (56.2 percent of males and 28.1 percent of females) in 2007.

Sport

Bhutan's national sport is archery, and competitions are held regularly in most villages. There are two targets placed over 100 metres apart and teams shoot from one end of the field to the other. Each member of the team shoots two arrows per round. Traditional Bhutanese archery is a social event and competitions are organized between villages, towns, and amateur teams. There is plenty of food and drink, as well as singing and dancing cheerleaders comprised of wives and supporters of the participating teams. Attempts to distract an opponent include standing around the target and making fun of the shooter's ability.

Darts ("khuru") is an equally popular outdoor team sport, in which heavy wooden darts pointed with a 10cm nail are thrown at a paperback-sized target 10 to 20 metres away. Another traditional sport is the "digor," which is like shot put combined with horseshoe throwing.

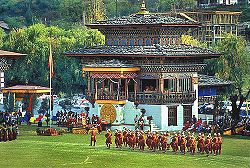

Football (soccer) is increasingly popular. In 2002, Bhutan's national football team played opposite Montserrat - billed as "The Other Final," the match took place on the same day Brazil played Germany in the World Cup Final, but at the time Bhutan and Montserrat were the world's two lowest ranked teams. The match was held in Thimphu's Changlimithang National Stadium, and Bhutan won 4-0.

Music and dance

"Rigsar" is the emergent style of popular music. Played on a mix of traditional instruments and electronic keyboards, it dates back to the early 1990s, and shows the influence of Indian popular music. Traditional genres include the "zhungdra" and "boedra."

Masked dances and dance dramas are common traditional features at festivals, usually accompanied by traditional music. Energetic dancers, wearing colorful wooden or composition facemasks and stylized costumes, depict heroes, demons, death heads, animals, gods, and caricatures of common people. The dancers enjoy royal patronage, and preserve ancient folk and religious customs and perpetuate the ancient lore and art of mask-making.

Bhutan has numerous public holidays, most of which centre around traditional seasonal, secular and religious festivals. They include the Dongzhi (winter solstice) (around January 1, depending on the lunar calendar), the lunar New Year (February or March), the king's birthday and the anniversary of his coronation, the official start of monsoon season (September 22), National Day (December 17), and various Buddhist and Hindu celebrations. Even the secular holidays have religious overtones, including religious dances and prayers for blessing the day.

Media

Bhutan has just one government newspaper (Kuensel) and two recently launched private newspapers, one government-owned television station and several FM radio stations.

In the early 1960s the third king of Bhutan began the gradual process of introducing modern technology to the medieval kingdom. The first radio service was broadcast for 30 minutes on Sundays (by what is now the Bhutan Broadcasting Service) beginning in 1973. The first television broadcasts were initiated in 1999, although a few wealthy families had bought satellite dishes earlier. Internet service was established in 2000.

In 2002 the first feature length movie was shot in Bhutan, the acclaimed "Travellers and Magicians" written and directed by Khyentse Norbu, the esteemed lama and head of the non-sectarian Khyentse lineage. The movie examines the pull of modernity on village life in Bhutan as colored by the Buddhist perspective of "tanha," or desire.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agarwala, A.P. 2003. Sikkim and Bhutan, Nest and Wings. New Delhi: Nest & Wings (India). ISBN 8187592079

- Armington, Stan. 1998. Bhutan. Hawthorn, Victoria: Lonely Planet. ISBN 0864424833

- Aris, Michael, and Michael Hutt, eds. Bhutan: Aspects of Culture and Development. 1994. Kiscadale Asia research series, no. 5. Gartmore, Scotland: Kiscadale. ISBN 9781870838177

- Coelho, Vincent Herbert. 1971. Sikkim and Bhutan. New Delhi: Indian Coucil for Cultural Relations.

- Crossette, Barbara. 1995. So Close to Heaven: The Vanishing Buddhist Kingdoms of the Himalayas. 1995. New York: A.A. Knopf. ISBN 067941827X

- Datta-Ray, Sunanda K. 1984. Smash and Grab: The Annexation of Sikkim. Vikas. ISBN 0706925092

- Foning, A. R. 1987. Lepcha, My Vanishing Tribe. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers. ISBN 8120706854

- Olschak, Blanche C. Bhutan: Land of Hidden Treasures. 1971.

- Rose, Leo. 1993. The Nepali Ethnic Community in the Northeast of the Subcontinent. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

External links

All links retrieved October 1, 2023.

- Bhutan Countries and Their Cultures.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.