Difference between revisions of "Northern Ireland" - New World Encyclopedia

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) m |

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 450: | Line 450: | ||

===Education=== | ===Education=== | ||

| − | + | Education in Northern Ireland differs slightly from systems used elsewhere in the [[United Kingdom]]. The [[Northern Ireland]] system emphasises a greater depth of education compared to the [[England|English]] and [[Wales|Welsh]] systems. A child's age on the July 1 determines the point of entry into the relevant stage of education unlike [[Great Britain]] where it is the September 1. Northern Ireland's results at GCSE and [[A-Level]] are consistently top in the UK. At A-Level, one third of students in Northern achieved A grades in 2007, compared to one quarter in England and Wales. | |

| − | Education in Northern Ireland differs slightly from systems used elsewhere in the [[United Kingdom]]. | + | |

| + | All schools in Northern Ireland follow the Northern Ireland Curriculum which is based on the National Curriculum used in England and Wales. At age 11, on entering secondary education, all pupils study a broad base of subjects which include Geography, English, Mathematics, Science, PE, Music and modern languages. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Primary education extends from age 4 to 11, when pupils sit the Eleven plus test, and the results determine which school they will go to. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * Secondary education | ||

| + | ** Secondary School or Grammar School | ||

| + | *** [[Key Stage 3]] | ||

| + | **** Year 8, age 11 to 12 (equivalent to Year 7 in England and Wales) | ||

| + | **** Year 9, age 12 to 13 | ||

| + | **** Year 10, age 13 to 14 | ||

| + | *** [[Key Stage 4]] | ||

| + | **** Year 11, age 14 to 15 | ||

| + | **** Year 12, age 15 to 16 ([[General Certificate of Secondary Education|GCSE]] examinations) | ||

| + | ** Secondary School, Grammar School, or [[Further Education College]] | ||

| + | *** [[Sixth form]] | ||

| + | **** Year 13, age 16 to 17 ([[Advanced Level (UK)|AS-level]] examinations) | ||

| + | **** Year 14, age 17 to 18 ([[Advanced Level (UK)|A-levels]] (A2)) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although religious [[Integrated Education]] is increasing, Northern Ireland has a highly segregated education system, with 95% of pupils attending either a maintained ([[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]]) school or a controlled school (mostly [[Protestantism|Protestant]]). However, controlled schools are open to children of all faiths and none. Teaching a balanced view of some subjects (especially regional history) is difficult in these conditions. The [[Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education]] (NICIE), a voluntary organisation, promotes, develops and supports Integrated Education in Northern Ireland. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | School holidays in Northern Ireland are considerably different from the rest of the [[United Kingdom]], and are more similar to those in the [[Republic of Ireland]]. Northern Irish schools often do not take a full week for half term holidays, and the Summer term does not usually have a half term at all. Christmas holidays sometimes consist of less than two weeks, the same with the [[Easter]] holiday. This does, however, vary considerably between schools. The major difference however is that summer holidays are considerably longer with the entirety of July and nearly all of August off, giving an eight week summer holiday. | ||

See: | See: | ||

| Line 736: | Line 760: | ||

* [http://www.culturenorthernireland.org culturenorthernireland.org] | * [http://www.culturenorthernireland.org culturenorthernireland.org] | ||

| − | {{credit|Northern_Ireland|154454832|History_of_Northern_Ireland|157480984|Ulster|157113267|The_Troubles|157434884Demography_and_politics_of_Northern_Ireland|155045091|County_Antrim|156395587|Economy_of_Northern_Ireland|153352305|Culture_of_Northern_Ireland|155375301}} | + | {{credit|Northern_Ireland|154454832|History_of_Northern_Ireland|157480984|Ulster|157113267|The_Troubles|157434884Demography_and_politics_of_Northern_Ireland|155045091|County_Antrim|156395587|Economy_of_Northern_Ireland|153352305|Education_in_Northern_Ireland|157076567|Culture_of_Northern_Ireland|155375301}} |

Revision as of 19:55, 13 September 2007

| Northern Ireland (English) Tuaisceart Éireann (Irish) Norlin Airlann1 (Ulster Scots) The Union Flag is the official flag used by the government to represent Northern Ireland. The former official flag, the Ulster Banner, continues to be used by groups (such as sports teams) representing the territory in an unofficial manner (see Northern Ireland flags issue).

| |

| Motto: Quis separabit? (Latin) "Who shall separate?" | |

| Anthem: "God Save the Queen" "Londonderry Air" (de facto) | |

|

Location of Northern Ireland (orange)

– on the European continent (camel white) – in the United Kingdom (camel) | |

| Capital | Belfast 54°35.456′N 5°50.4′W |

|---|---|

| Largest city | capital |

| Official languages | English (de facto), Irish and Ulster Scots2 |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

| - Queen | Queen Elizabeth II |

| - Prime Minister | Gordon Brown MP |

| - First Minister | Ian Paisley MLA |

| - Deputy First Minister | Martin McGuinness MLA |

| - Secretary of State | Shaun Woodward MP |

| Establishment | |

| - Government of Ireland Act | 1920 |

| Area | |

| - Total | 13,843 km² 5,345 sq mi |

| Population | |

| - 2004 estimate | 1,710,300 |

| - 2001 census | 1,685,267 |

| - Density | 122/km² 315/sq mi |

| GDP (PPP) | 2002 estimate |

| - Total | $33.2 billion |

| - Per capita | $19,603 |

| Currency | Pound sterling (GBP)

|

| Time zone | GMT (UTC+0) |

| - Summer (DST) | BST (UTC+1) |

| Internet TLD | .uk3 |

| Calling code | +44 |

Northern Ireland (Irish: Tuaisceart Éireann) is a part of the United Kingdom lying in the northeast of the island of Ireland.

Northern Ireland consists of six of the nine counties of the province of Ulster. The remainder of the island of Ireland is a sovereign state, the Republic of Ireland.

Northern Ireland has been for many years the site of a violent and bitter ethno-political conflict between those claiming to represent Nationalists, who are predominantly Catholic, and those claiming to represent Unionists, who are predominantly Protestant.

In general, Nationalists want Northern Ireland to be unified with the Republic of Ireland, and Unionists want it to remain part of the United Kingdom. Unionists are in the majority in Northern Ireland, though Nationalists represent a significant minority. In general, Protestants consider themselves British and Catholics see themselves as Irish but there are some who claim dual nationality.

The campaigns of violence have become known popularly as The Troubles. The majority of both sides of the community have had no direct involvement in the violent campaigns waged. Since the signing of the Belfast Agreement in 1998, many of the major paramilitary campaigns have either been on ceasefire or have declared their war to be over.

Geography

Northern Ireland covers 5459 square miles (14,139 square kilometers), about a sixth of the island's total area, or a little larger than the U.S. state of Maryland.

The largest island of Northern Ireland is Rathlin, off the Antrim coast. Strangford Lough is the largest inlet in the British Isles, covering 150 square kilometres.

Northern Ireland was covered by an ice sheet for most of the last ice age and on numerous previous occasions, the legacy of which can be seen in the extensive coverage of drumlins in Counties Fermanagh, Armagh, Antrim and particularly Down. The volcanic activity which created the Antrim Plateau also formed the eerily geometric pillars of the Giant's Causeway on the north Antrim coast. Also in north Antrim are the Carrick-a-Rede Rope Bridge, Mussenden Temple and the Glens of Antrim.

There are substantial uplands in the Sperrin Mountains (an extension of the Caledonian fold mountains) with extensive gold deposits, granite Mourne Mountains and basalt Antrim Plateau, as well as smaller ranges in South Armagh and along the Fermanagh–Tyrone border. None of the hills are especially high, with Slieve Donard in the dramatic Mournes reaching 2782 feet, (848 meters) Northern Ireland's highest point. Belfast's most prominent peak is Cave Hill.

The whole of Northern Ireland has a temperate maritime climate, rather wetter in the west than the east, although cloud cover is persistent across the region. The weather is unpredictable at all times of the year, and although the seasons are distinct, they are considerably less pronounced than in interior Europe or the eastern seaboard of North America. Average daytime maximums in Belfast are 43.7°F (6.5°C) in January and 63.5°F (17.5°C) in July. The damp climate and extensive deforestation in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries resulted in much of the region being covered in rich green grassland.

The centrepiece of Northern Ireland's geography is Lough Neagh, at 151 square miles (392 square kilometers) the largest freshwater lake both on the island of Ireland and in the British Isles. A second extensive lake system is centred on Lower and Upper Lough Erne in Fermanagh.

The Lower and Upper River Bann, River Foyle and River Blackwater form extensive fertile lowlands, with excellent arable land also found in North and East Down, although much of the hill country is marginal and suitable largely for animal husbandry.

Notable is the absence of trees. Most of the land has been plowed, drained, and cultivated for centuries. About 5 percent of the land was under forest in 2007, most planted by the state, economically unimportant, but helps to diversify the landscape.

The fauna of Northern Ireland is similar to that of Great Britain, with fewer species. Only the Irish stoat, the Irish hare, and three species of birds are exclusively Irish, although the region is rich in fish, particularly pike, perch, trout, and salmon. There are about 40 nature reserves and several bird sanctuaries.

Natural hazards include winter windstorms and floods. Environmental issues include sewage treatment, that the European Commission in 2003 alleged was inadequate.

The valley of the River Lagan is dominated by Northern Ireland's capital city, Belfast, whose metropolitan area included 276,459 people in 2001, over a third of the population of Northern Ireland. With heavy urbanisation and industrialisation along the Lagan Valley and both shores of Belfast Lough, it is the largest city in Northern Ireland and the province of Ulster, and the second-largest city on the island of Ireland (after Dublin).Other cities include Armagh, Londonderry, Lisburn, and Newry.

History

Stone age

A long cold climatic spell prevailed until about 9000 years ago, and most of Ireland was covered with ice. This era was known as the Ice Age. Sea-levels were lower then, and Ireland, as with its neighbour Britain, instead of being islands, were part of a greater continental Europe. Mesolithic middle stone age inhabitants arrived some time after 8000 B.C.E. About 4000 B.C.E., sheep, goats, cattle and cereals were imported from southwest continental Europe. The Giant's Ring is a henge monument at Ballynahatty, near Belfast, which consists of a circular enclosure, 590 feet (200 meters) in diameter, surrounded with an 15 feet (four-meter) high earthwork bank with five entrances, and a small neolithic passage grave slightly off-centre. The tomb is believed to date from around 3000 B.C.E., and the bank slightly later.

Celtic colonisation

The main Celtic arrivals occurred in the Iron Age. The Celts, an Indo-European group who are thought to have originated in the second millennium B.C.E. in east-central Europe, are traditionally thought to have colonised Ireland in a series of waves between the eighth and first centuries B.C.E., with the Gaels, the last wave of Celts, conquering the island.

The Romans referred to Ireland as Hibernia. Ptolemy in 100 C.E. recorded Ireland's geography and tribes. Ireland was never formally a part of the Roman Empire.

The Five Fifths

Ireland was organized into a number of independent petty kingdoms, or tuatha (clans), each with an elected king. The country coalesced into five groups of tuatha, known as the Five Fifths (Cuíg Cuígí), about the beginning of the Christian era. These were Ulster, Meath, Leinster, Munster, and Connaught.

Each king was surrounded by an aristocracy, with clearly defined land and property rights, and whose main wealth was in cattle. Céilí, or clients supported greater landowners by tilling the soil and tending the cattle. Individual families were the basic units of society, both to control land and enforce the law.

Society was based on cattle rearing and agriculture. The principal crops were wheat, barley, oats, flax, and hay. Plows drawn by oxen were used to till the land. Sheep were bred for wool, and pigs for slaughter. Fishing, hunting, fowling, and trapping provided further food. Dwellings were built by the post-and-wattle technique, and some were situated within ring forts.

Each of the Five Fifths had its own king, although Ulster in the north was dominant at first. Niall Noigiallach (died c.450/455) laid the basis for the Uí Néill dynasty's hegemony, which ruled over much of western, northern and central Ireland from their base in Tír Eóghain (Eoghan's Country) - modern County Tyrone. By the time he died, hegemony had passed to his midland kingdom of Meath. In the sixth century, descendants of Niall, ruling at Tara in northern Leinster, claimed to be overkings of Ulster, Connaught, and Meath, and later, they claimed to be kings of all of Ireland.

The written judicial system was the Brehon Law, and it was administered by professional learned jurists who were known as the Brehons.

Raids on England

From the mid-third century C.E., the Irish, who were at that time called Scoti rather than the older term Hiberni carried out frequent raiding expeditions on England. Raids became incessant in the second half of the fourth century, when Roman power in Britain was beginning to crumble. The Irish settled along the west coast of Britain, Wales and Scotland.

Saints Palladius and Patrick

According to early medieval chronicles, in 431, Bishop Palladius arrived in Ireland on a mission from Pope Celestine to minister to the Irish "already believing in Christ." The same chronicles record that Saint Patrick, Ireland's patron saint, arrived in 432. There is continued debate over the missions of Palladius and Patrick, but the general consensus is that they both existed and that seventh century annalists may have mis-attributed some of their activities to each other. Palladius most likely went to Leinster, while Patrick went to Ulster, where he probably spent time in captivity as a young man. He established his centre in Armagh, which remained the primatial see of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland and the Protestant Church of Ireland.

Patrick is traditionally credited with preserving the tribal and social patterns of the Irish, codifying their laws and changing only those that conflicted with Christian practices. He is also credited with introducing the Roman alphabet, which enabled Irish monks to preserve parts of the extensive Celtic oral literature. The historicity of these claims remains the subject of debate. There were Christians in Ireland long before Patrick came, and pagans long after he died. However, it is undoubtedly true that Patrick played a crucial role in transforming Irish society.

The druid tradition collapsed in the face of the spread of the new religion. Irish Christian scholars excelled in the study of Latin and Greek learning and Christian theology in the monasteries that flourished, preserving Latin and Greek learning during the Early Middle Ages. The arts of manuscript illumination, metalworking, and sculpture flourished and produced such treasures as the Book of Kells, ornate jewellery, and the many carved stone crosses that dot the island.

English raid

In 684 C.E., an English expeditionary force sent by Northumbrian King Ecgfrith invaded Ireland in the summer of that year. The English forces managed to seize a number of captives and booty, but they apparently did not stay in Ireland for long. The next English involvement in Ireland would take place a little more than half a millennium later in 1169 when the Normans invaded the country.

Irish monasticism

Christian settlements in Ireland were loosely linked, usually under the auspices of a great saint. By the late sixth century, numerous Irishmen devoted themselves to an austere existence as monks, hermits, and as missionaries to pagan tribes in Scotland, the north of England, and in west-central Europe. A comprehensive monastic system developed in Ireland, partly through the influenced by Celtic monasteries in Britain, through the sixth and seventh centuries.

The monasteries became notable centres of learning. Christianity brought Latin, Irish scribes produced manuscripts written in the Insular style, which spread to Anglo-Saxon England and to Irish monasteries on the European continent. Initial letters were illuminated. The most famous Irish manuscript is the Book of Kells, a copy of the four Gospels probably dating from the late eighth century, while the earliest surviving illuminated manuscript is the Book of Durrow, probably made 100 years earlier.

Viking raiders

The first recorded Viking raid in Irish history occurred in 795 when Vikings from Norway looted the island of Lambay, located off the Dublin coast. Early Viking raids were generally small in scale and quick. These early raids interrupted the golden age of Christian Irish culture starting the beginning of two hundred years of intermittent warfare, with waves of Viking raiders plundering monasteries and towns throughout Ireland. By the early 840s, the Vikings began to establish settlements along the Irish coasts and to spend the winter months there. Vikings founded settlements in Limerick, Waterford, Wexford, Cork, Arklow and most famously, Dublin. Written accounts from this time (early to mid 840s) show that the Vikings were moving further inland to attack (often using rivers such as the Shannon) and then retreating to their coastal headquarters. The Vikings became traders and their towns became a new part of the life of the country. However, the Vikings never achieved total domination of Ireland, often fighting for and against various Irish kings, such as Flann Sinna, Cerball mac Dúnlainge and Niall Glúndub. Ultimately they were suborned by King Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill of Meath at the battle of Tara in 980.

First king of Ireland

Two branches of Niall's descendants, the Cenél nEogain, of the northern Uí Néill, and the Clan Cholmáin, of the southern Uí Néill, alternated as kings of Ireland from 734 to 1002. Brian Boru (941 - 1014) became the first high king of all Ireland (árd rí Éireann) in 1002. King Brian Boru subsequently united most of the Irish Kings and Chieftains to defeat the Danish King of Dublin who led an army of Irish and Vikings at the Battle of Clontarfin 1014.

The Anglo-Norman invasion

By the twelfth century, Ireland was divided politically into a shifting hierarchy of petty kingdoms and over-kingdoms. Power was exercised by the heads of a few regional dynasties vying against each other for supremacy over the whole island. One of these, the King of Leinster Diarmait Mac Murchada was forcibly exiled from his kingdom by the new High King, Ruaidri mac Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair. Fleeing to Aquitaine, Diarmait obtained permission from Henry II to use the Norman forces to regain his kingdom. The first Norman knight landed in Ireland in 1167, followed by the main forces of Normans, Welsh and Flemings in Wexford in 1169. Within a short time Leinster was regained, Waterford and Dublin were under the control of Diarmait, who named his son-in-law, Richard de Clare, heir to his kingdom. This caused consternation to King Henry II of England, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to establish his authority.

With the authority of the papal bull Laudabiliter from Adrian IV, Henry landed with a large fleet at Waterford in 1171, becoming the first King of England to set foot on Irish soil. Henry awarded his Irish territories to his younger son John with the title Dominus Hiberniae ("Lord of Ireland"). When John unexpectedly succeeded his brother as King John, the "Lordship of Ireland" fell directly under the English Crown.

After the Norman invasion of Ireland in the twelfth century, the east of Ulster fell by conquest to Norman barons, first De Courcy (died 1219), then Hugh de Lacy (1176-1243), who founded the Earldom of Ulster - based around the modern counties of Antrim and Down.

The Lordship of Ireland

Initially the Normans controlled the entire east coast, from Waterford up to eastern Ulster and penetrated as far west as Galway, Kerry and Mayo. The most powerful lords in the land were the great Hiberno-Norman Lord of Leinster from 1171, Earl of Meath from 1172, Earl of Ulster from 1205, Earl of Connaught from 1236, Earl of Kildare from 1316, the Earl of Ormonde from 1328 and the Earl of Desmond from 1329 who controlled vast territories, known as Liberties which functioned as self-administered jurisdictions with the Lordship of Ireland owing feudal fealty to the King in London. The first Lord of Ireland was King John, who visited Ireland in 1185 and 1210 and helped consolidate the Norman controlled areas, while at the same time ensuring that the many Irish kings swore fealty to him.

The Norman-Irish established the feudal system throughout most of lowland Ireland, characterised by baronies, manors, towns and large land-owning monastic communities, and the county system. King John established a civil government independent of the feudal lords. The country was divided into counties for administrative purposes, English law was introduced, and attempts were made to reduce the feudal liberties, which were lands held in the personal control of aristocratic families and the church. The Irish Parliament paralleled that of its English counterpart.

Throughout the thirteenth century the policy of the English Kings was to weaken the power of the Norman Lords in Ireland.

Gaelic resurgence

By 1261 the weakening of the Anglo-Normans had become manifest when Fineen Mac Carthy defeated a Norman army at the Battle of Callann, County Kerry, and killed John fitz Thomas, Lord of Desmond, his son Maurice fitz John and eight other Barons. In 1315, Edward Bruce of Scotland invaded Ireland, gaining the support of many Gaelic lords against the English. Although Bruce was eventually defeated at the Battle of Faughart, the war caused a great deal of destruction, especially around Dublin. In this chaotic situation, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land that their families had lost since the conquest and held them after the war was over.

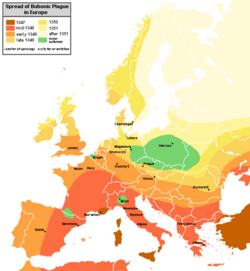

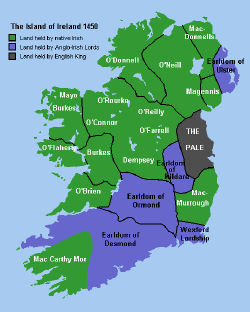

The Black Death arrived in Ireland in 1348. Because most of the English and Norman inhabitants of Ireland lived in towns and villages, the plague hit them far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. After it had passed, Gaelic Irish language and customs came to dominate the country again. The English-controlled area shrunk back to the Pale, a fortified area around Dublin that ran through the counties of Louth, Meath, Kildare and Wicklow and the Earldoms of Kildare, Ormonde and Desmond.

Outside the Pale, the Hiberno-Norman lords adopted the Irish language and customs, becoming known as the Old English, and in the words of a contemporary English commentator, became "more Irish than the Irish themselves." Over the following centuries they sided with the indigenous Irish in political and military conflicts with England and generally stayed Catholic after the Reformation.

By the end of the fifteenth century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared. England's attentions were diverted by its Wars of the Roses (civil war). The Lordship of Ireland lay in the hands of the powerful Fitzgerald Earl of Kildare, who dominated the country by means of military force and alliances with lords and clans around Ireland. Around the country, local Gaelic and Gaelicised lords expanded their powers at the expense of the English government in Dublin.

The Reformation

The Reformation, before which, in 1532, Henry VIII broke with Papal authority, fundamentally changed Ireland. While Henry VIII broke English Catholicism from Rome, his son Edward VI moved further, breaking with Papal doctrine completely. While the English, the Welsh and, later, the Scots accepted Protestantism, the Irish remained Catholic. This influenced their relationship with England for the next four hundred years, as the Reformation coincided with a determined effort on behalf of the English to re-conquer and colonise Ireland. This sectarian difference meant that the native Irish and the (Roman Catholic) Old English were excluded from political power.

Re-conquest and rebellion

From 1536, Henry VIII decided to re-conquer Ireland. The Fitzgerald dynasty of Kildare, who had become the effective rulers of Ireland in the fifteenth century, had invited Burgundian troops into Dublin to crown the Yorkist pretender, Lambert Simnel as King of England in 1497. Again in 1536, Silken Thomas Fitzgerald went into open rebellion against the crown. Having put down this rebellion, Henry VIII resolved to bring Ireland under English government control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England.

In 1541, Henry upgraded Ireland from a lordship to a full Kingdom, and Henry was proclaimed King of Ireland at a meeting of the Irish Parliament attended by the Gaelic Irish chieftains as well as the Hiberno-Norman aristocracy. The re-conquest was completed during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I, after several bloody conflicts—the Desmond Rebellions (1569–1573 and 1579–1583 and the Nine Years War 1594–1603.

In the 1600s Ulster was the last redoubt of the traditional Gaelic way of life, and following the defeat of the Irish forces in the Nine Years War at the battle of Kinsale (1601), Elizabeth I's English forces succeeded in subjugating Ulster and all of Ireland. The Gaelic leaders of Ulster, the O'Neills and O'Donnells, finding their power under English suzerainty limited, decamped en masse in 1607 (the Flight of the Earls) to Roman Catholic Europe. This allowed the Crown to settle Ulster with more loyal English and Scottish planters, a process which began in earnest in 1610.

After this point, the English authorities in Dublin established real control over Ireland for the first time, bringing a centralised government to the entire island, and successfully disarmed the native lordships. However, the English were not successful in converting the Catholic Irish to the Protestant religion and the brutal methods used by crown authority to pacify the country heightened resentment of English rule.

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster, run by the government, settled only the counties confiscated from those Irish families that had taken part in the Nine Years War. The Crown dispossessed thousands of the native Irish, who were forced to move to poorer land. Counties Donegal, Tyrone, Armagh, Cavan, Londonderry and Fermanagh comprised the official plantation. Confiscated territory was granted to new landowners provided they would establish settlers as their tenants, and that they would introduce English law and the Protestant religion.

However, the most extensive settlement in Ulster of English, Scots and Welsh — as well as Protestants from throughout the European continent — occurred in Antrim and Down. These counties, though not officially planted, had suffered de-populatation during the war and proved attractive to settlers from nearby Scotland. This unofficial settlement continued well into the eighteenth century, interrupted only by the Catholic uprising of 1641.

Catholic uprising

This rebellion, initially led by Phelim O'Neill, was intended to seize power rapidly, but quickly degenerated into attacks on Protestant settlers. Dispossessed Catholics slaughtered thousands of Protestants, an event which remains strong in Ulster Protestant folk-memory. In the ensuing wars (1641 - 1653, fought against the background of civil war in England, Scotland and Ireland), Ulster became a battleground between the Protestant settlers and the native Irish Catholics. In 1646, the Irish Catholic army under Owen Roe O'Neill inflicted a bloody defeat on a Scottish Covenanter army at Benburb in County Tyrone, but the Catholic forces failed to follow up their victory and the war lapsed into stalemate. The war in Ulster ended with the defeat of the Irish Catholic army at the Battle of Scarrifholis on the western outskirts of Letterkenny, County Donegal, in 1650 and the occupation of the province by Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army. The atrocities committed by all sides in the war poisoned the relationships between Ulster's ethno-religious communities for generations afterwards.

The Williamite war

Forty years later, in 1688-1691, the former warring parties re-fought the conflict in the Williamite war in Ireland, when Irish Catholics ("Jacobites") supported James II (deposed in the Glorious Revolution) and Ulster Protestants (Williamites) backed William of Orange. At the start of the war, Irish Catholic Jacobites controlled all of Ireland for James, with the exception of the Protestant strongholds at Derry and at Enniskillen in Ulster. The Jacobites besieged Derry from December 1688 to July 1689, when a Williamite army from Britain relieved the city. The Protestant Williamite fighters based in Enniskillen defeated another Jacobite army at the battle of Newtownbutler on July 28, 1689.

Thereafter, Ulster remained firmly under Williamite control and William's forces completed their conquest of the rest of Ireland in the next two years. Ulster Protestant irregulars known as "Enniskilleners" served with the Williamite forces. The war provided Protestant loyalists with the iconic victories of the Siege of Derry, the Battle of the Boyne (July 1, 1690)and the Battle of Aughrim (July 12, 1691), all of which their descendants still commemorate today.

The Williamites' victory in this war ensured British and Protestant supremacy in Ireland for over 100 years. The Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland excluded most of Ulster's population from power on religious grounds. Roman Catholics (descended from the indigenous Irish) and Presbyterians (mainly descended from Scottish planters, but also from indigenous Irishmen who converted to Presbyterianism) both suffered discrimination under the Penal Laws, which gave full political rights only to Anglican Protestants (mostly descended from English settlers). In the 1690s, Scottish Presbyterians became a majority in Ulster, tens of thousands of them having emigrated there to escape a famine in Scotland.

Colonial Ireland 1691-1801

Subsequent Irish antagonism towards England was aggravated by the economic situation of Ireland in the eighteenth century. Some absentee landlords managed some of their estates inefficiently, and food tended to be produced for export rather than for domestic consumption. Two very cold winters led directly to the Great Irish Famine (1740-1741), which killed about 400,000 people; all of Europe was affected. In addition, Irish exports were reduced by the Navigation Acts from the 1660s, which placed tariffs on Irish produce entering England, but exempted English goods from tariffs on entering Ireland.

Considerable numbers of Ulster-Scots just a few generations after arriving in Ulster migrated to the North American colonies throughout the eighteenth century (250,000 settled in what would become the United States between 1717 and 1770 alone). According to Kerby Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (1988), Protestants were one-third of the population of Ireland, but three-quarters of all emigrants from 1700 to 1776; 70% of these Protestants were Presbyterians.

Sectarian violence

Political tensions resurfaced, albeit in a new form, towards the end of the 18th century. In the 1790s many Catholics and Presbyterians, in opposition to Anglican domination and inspired by the American and French revolutions joined together in the United Irishmen movement. This group (founded in Belfast) dedicated itself to founding a non-sectarian and independent Irish republic. The United Irishmen had particular strength in Belfast, Antrim and Down.

Paradoxically however, this period also saw much sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants, principally members of the Church of Ireland (Anglicans, who practised the state religion and had rights denied to both Presbyterians and Catholics), notably the "battle of the Diamond" in 1795, a faction fight between the rival "Defenders" (Catholic) and "Peep O'Day Boys" (Anglican), which led to over 100 deaths and to the founding of the Orange Order.

This event, and many others like it, came about with the relaxation of the Penal Laws and as Catholics began to purchase land and involve themselves in the linen trade (activities which previously had involved many onerous restrictions). Protestants, including Presbyterians, who in some parts of the province had come to identify with the Catholic community, used violence to intimidate Catholics who tried to enter the linen trade. Estimates suggest that up to 7000 Catholics suffered expulsion from Ulster during this violence. Many of them settled in northern Connacht. Loyalist militias, primarily Anglicans, also used violence against the United Irishmen and against Catholic and Protestant republicans throughout the province.

In 1798 the United Irishmen, led by Henry Joy McCracken, launched a rebellion in Ulster, mostly supported by Presbyterians. But the British authorities swiftly put down the insurgents and employed severe repression after the fighting had ended. In the wake of the failure of this rebellion, and following the gradual abolition of official religious discrimination after the Act of Union in 1800, Presbyterians came to identify more with the State and with their Anglican neighbours, who perceived them as the lesser of two evils.

Union with Great Britain

Largely in response to the 1798 rebellion, Irish self-government was abolished altogether by the Act of Union on January 1, 1801, which merged Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain (itself a union of England and Scotland, created almost 100 years earlier), to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Part of the agreement was that Catholic Emancipation would be conceded to remove discrimination against Catholics, Presbyterians, and others. However, King George III controversially blocked any change. In 1823, an enterprising Catholic lawyer, Daniel O'Connell, known as "the Great Liberator" began a successful campaign to achieve emancipation, which was finally conceded in 1829. He later led an unsuccessful campaign for "Repeal of the Act of Union."

The second of Ireland's "great famines," An Gorta Mór struck the country severely in the period 1845-1849, with potato blight leading to mass starvation and emigration. The impact of emigration in Ireland was severe; the population dropped from over eight million before the Famine to 4.4 million in 1911. The Irish language, once the spoken language of the entire island, declined in use sharply in the nineteenth century as a result of the famine and the creation of the National School education system, as well as hostility to the language from leading Irish politicians of the time; it was largely replaced by English.

Outside mainstream nationalism, a series of violent rebellions by Irish republicans took place in 1803, under Robert Emmet; in 1848 a rebellion by the Young Irelanders, most prominent among them, Thomas Francis Meagher; and in 1867, another insurrection by the Irish Republican Brotherhood. All failed, but physical force nationalism remained an undercurrent in the nineteenth century.

Land reform

The late nineteenth century also witnessed major land reform, spearheaded by the Land League under Michael Davitt demanding what became known as the 3 Fs; Fair rent, free sale, fixity of tenure. From 1870 various British governments introduced a series of Irish Land Acts - William O'Brien playing a leading role by winning the greatest piece of social legislation Ireland had yet seen, the Wyndham Land Purchase Act (1903) which broke up large estates and gradually gave rural landholders and tenants ownership of the lands. It effectively ended absentee landlordism, solving the age old Irish Land Question

In the 1870s the issue of Irish self-government again became a focus of debate under Protestant landowner, Charles Stewart Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party of which he was founder. British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone made two unsuccessful attempts to introduce Home Rule in 1886 and 1893. Parnell's controversial leadership eventually ended when he was implicated in a divorce scandal, when it was revealed that he had been living in family relationship with Katherine O'Shea, the long separated wife of a fellow Irish MP, with whom he was father of three children.

The Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 broke the power of the landlord dominated "Grand Juries," passing for the first time absolute democratic control of local affairs into the hands of the people through elected Local County Councils.

Ulster prospers

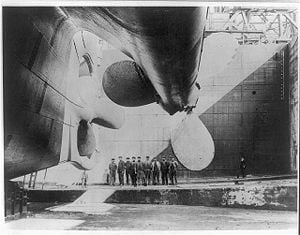

In the nineteenth century, Ulster became the most prosperous province in Ireland, with the only large-scale industrialisation in the country. In the latter part of the century, Belfast overtook Dublin as the largest city on the island. Belfast became famous in this period for its huge dockyards and shipbuilding - and notably for the construction of the RMS Titanic.

Nationalist-Unionist tension appears

The origins of Northern Ireland's politics lie in late nineteenth century disputes over Home Rule for Ireland, which Ulster Protestants usually opposed - fearing for their status in an autonomous Catholic-dominated Ireland and also not trusting politicians from the agrarian south and west to support the more industrial economy of Ulster. Sectarian divisions in Ulster became hardened into the political categories of unionist (supporters of the Union with Britain, mostly (but not exclusively) Protestant) and nationalist (advocates of an Irish self-government, usually (though not exclusively) Catholic). Out of this division, two opposing sectarian movements evolved, the Protestant Orange Order and the Catholic Ancient Order of Hibernians.

Home Rule became certain when in 1910 the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) under John Redmond held the balance of power in the Commons and the third Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1912. To resist Home Rule, thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson and James Craig, signed the "Ulster Covenant" of 1912, pledging to resist Irish independence. This movement also saw the setting up of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), the first Irish paramilitary group, in order to resist British attempts to enforce Home Rule. In response, Irish nationalists created the Irish Volunteers - forerunners of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) - to ensure the passing of the Home Rule Act 1914.

In the Larne Gun Running incident in 1912, thousands of rifles and rounds of ammunition were smuggled from Imperial Germany for the Ulster Volunteer Force.

Unionists were in a minority on the island of Ireland as a whole, but were a majority in the northern province of Ulster, a large majority in the counties of Antrim and Down, small majorities in the counties of Armagh and Londonderry (also known as Derry), with substantial numbers also concentrated in the nationalist-majority counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone.

World War I

In September 1914, just as the First World War broke out, the UK Parliament finally passed the Third Home Rule Act to establish self-government for Ireland, but was suspended for the duration of the war. Nationalist leaders and the IPP under Redmond in order to ensure the implementation of Home Rule after the war, supported the British and Allied war effort against the Central Powers.

The outbreak of the Great War in 1914, in which thousands of Ulstermen and Irishmen of all religions and sects volunteered and died, interrupted this armed stand-off. In particular, the heavy casualties of the 36th Ulster Division (largely composed of volunteers from the UVF) became a source both of mourning and of pride for the loyalist community, and remains so to the present day.

Before the war ended, Britain made two concerted efforts to implement Home Rule, one in May 1916 and again with the Irish Convention during 1917-1918, but the Irish sides (Nationalist, Unionist) were unable to agree terms for the temporary or permanent exclusion of Ulster from its provisions.

Easter 1916 uprising

A failed attempt was made to gain separate independence for Ireland with the 1916 Easter Rising, an insurrection in Dublin. Though support for the insurgents was small, the violence used in its suppression led to a swing in support of the rebels. In addition, the unprecedented threat of Irishmen being conscripted to the British Army in 1918 (for service on the Western Front as a result of the German Spring Offensive) accelerated this change. In the December 1918 elections most voters voted for Sinn Féin, the party of the rebels. Having won three-quarters of all the seats in Ireland, its MPs assembled in Dublin on January 21, 1919, to form a 32-county Irish Republic parliament, Dáil Éireann unilaterally, asserting sovereignty over the entire island.

Irish War of Independence

Unwilling to negotiate any understanding with Britain short of complete independence, the Irish Republican Army — the army of the newly declared Irish Republic — waged a guerilla war (the Irish War of Independence) from 1919 to 1921. In the course of the fighting and amid much acrimony, the Fourth Government of Ireland Act 1920 implemented Home Rule while separating the island into what the British government's Act termed "Northern Ireland" and "Southern Ireland."

In Ulster, the fighting generally took the form of street battles between Protestants and Catholics in the city of Belfast. Estimates suggest that about 600 civilians died in this communal violence, the majority of them (58 percent)Catholics. The IRA remained relatively quiescent in Ulster, with the exception of the south Armagh area, where Frank Aiken led it. Alot of I.R.A. activity also took place at this time in County Donegal and the City of Derry, where one of the main Republican leaders was Peadar O'Donnell. Hugh O'Doherty, a Sinn Féin politician, was elected Mayor of Derry at this time. In the First Dáil, which was elected in late 1918, Prof. Eoin Mac Néill served as the Sinn Féin T.D. for Derry City.

Anglo-Irish Treaty

In mid-1921, the Irish and British governments signed a truce that halted the war. In December 1921, representatives of both governments signed an Anglo-Irish Treaty. This abolished the Irish Republic and created the Irish Free State, a self-governing Dominion of the British Empire in the manner of Canada and Australia. Under the Treaty, Northern Ireland could opt out of the Free State and stay within the United Kingdom: it promptly did so. Six of the nine Ulster counties in the north-east formed Northern Ireland and the remaining three counties joined those of Leinster, Munster and Connacht to form Southern Ireland.

In 1922, both parliaments ratified the Treaty, formalising independence for the 26-county Irish Free State (which went on to become the Republic of Ireland in 1949); while the six county Northern Ireland, gaining Home Rule for itself, remained part of the United Kingdom. For most of the next 75 years, each territory was strongly aligned to either Catholic or Protestant ideologies, although this was more marked in the six counties of Northern Ireland.

The treaty to sever the union divided the Irish Free State republican movement into anti-Treaty (who wanted to fight on until an Irish Republic was achieved) and pro-Treaty supporters (who accepted the Free State as a first step towards full independence and unity). Between 1922 and 1923 both sides fought the bloody Irish Civil War. The new Irish Free State government defeated the anti-Treaty remnant of the Irish Republican Army.

Irish Free State

The new Irish Free State (1922–37) existed against the backdrop of the growth of dictatorships in mainland Europe and a major world economic downturn in 1929. In contrast with many contemporary European states it remained a democracy. Testament to this came when the losing faction in the Irish civil war, Eamon de Valera's Fianna Fáil, was able to take power peacefully by winning the 1932 general election. Nevertheless, up until the mid 1930s, considerable parts of Irish society saw the Free State through the prism of the civil war, as a repressive, British imposed state. It was only the peaceful change of government in 1932 that signalled the final acceptance of the Free State on their part. In contrast to many other states in the period, the Free State remained financially solvent as a result of low government expenditure. However, unemployment and emigration were high. The population declined to a low of 2.7 million recorded in the 1961 census.

The Roman Catholic Church had a powerful influence over the Irish state for much of its history. The clergy's influence meant that the Irish state had very conservative social policies, banning, for example, divorce, contraception, abortion, pornography as well as encouraging the censoring of many books and films. In addition the Church largely controlled the State's hospitals, schools and remained the largest provider of many other social services.

With the partition of Ireland in 1922, 92.6 percent of the Free State's population were Catholic while 7.4 percent were Protestant. By the 1960s, the Protestant population had fallen by half. Although emigration was high among all the population, due to a lack of economic opportunity, the rate of Protestant emigration was disproportionate in this period. Many Protestants left the country in the early 1920s. The Catholic Church had also issued a decree, known as Ne Temere, whereby the children of marriages between Catholics and Protestants had to be brought up as Catholics. From 1945, the emigration rate of Protestants fell and they became less likely to emigrate than Catholics - indicating their integration into the life of the Irish State.

World War II

In 1937, a new Constitution of Ireland proclaimed the state of Éire (or Ireland). The state remained neutral throughout World War II, a time termed The Emergency, and this saved it from much of the horrors of the war, although tens of thousands volunteered to serve in the British forces. Ireland was also hit badly by rationing of food, and coal in particular (peat production became a priority during this time). Though nominally neutral, recent studies have suggested a far greater level of involvement by the South with the Allies than was realised, with D Day's date set on the basis of secret weather information on Atlantic storms supplied by Éire.

In June 1940, to encourage the Irish state to join with the Allies, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill indicated to the Taoiseach Éamon de Valera that the United Kingdom would push for Irish unity, but believing that Churchill could not deliver, de Valera declined the offer. The British did not inform the Northern Ireland government that they had made the offer to the Dublin government, and De Valera's rejection was not publicized until 1970.

Republic declared

In 1949 the state was formally declared the Republic of Ireland and it left the British Commonwealth. In the 1960s, Ireland underwent a major economic change under reforming Taoiseach (prime minister) Seán Lemass and Secretary of the Department of Finance T.K. Whitaker, who produced a series of economic plans. Free second-level education was introduced by Donnchadh O'Malley as Minister for Education in 1968. From the early 1960s, the Republic sought admission to the European Economic Community but, because 90 percent of the export economy still depended on the United Kingdom market, it could not do so until the UK did, in 1973.

The Ireland Act 1949 gave the first legal guarantee to the Parliament and Government that Northern Ireland would not cease to be part of the United Kingdom without consent of the majority of its citizens, and this was most recently reaffirmed by the Northern Ireland Act 1998.

Stagnation

Global economic problems in the 1970s, augmented by a set of misjudged economic policies followed by governments, including that of Taoiseach Jack Lynch, caused the Irish economy to stagnate. The Troubles in Northern Ireland discouraged foreign investment. Devaluation was enabled when the Irish Pound, or Punt, was established in as a truly separate currency in 1979, breaking the link with the UK's sterling.

A plebiscite within Northern Ireland on whether it should remain in the United Kingdom, or join the Republic, was held in 1973. The vote went heavily in favour (98.9%) of maintaining the status quo with approximately 57.5% of the total electorate voting in support, but most nationalists boycotted the poll (see Northern Ireland referendum, 1973 for more). Though legal provision remains for holding another plebiscite, and former Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble some years ago advocated the holding of such a vote, no plans for such a vote have been adopted as of 2007.

The Troubles

The Troubles is a term used to describe the latest installment of periodic communal violence involving Republican and Loyalist paramilitary organisations, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the British Army and others in Northern Ireland from the late 1960s until the Belfast Agreement of April 10, 1998. The Troubles consisted of about 30 years of repeated acts of intense violence between elements of Northern Ireland's nationalist community (principally Roman Catholic) and unionist community (principally Protestant). The conflict was caused by the disputed status of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom and the domination of the minority nationalist community, and alleged discrimination against them, by the unionist majority. The violence was characterised by the armed campaigns of paramilitary groups. Most notable of these was the Provisional IRA campaign of 1969–1997 which was aimed at the end of British rule in Northern Ireland and the creation of a new, "all-Ireland," Irish Republic.

Celtic tiger unleashed

However, economic reforms in the late 1980s, the end of the Troubles, helped by investment from the European Community, led to the emergence of one of the world's highest economic growth rates, with mass immigration (particularly of people from Asia and Eastern Europe) as a feature of the late 1990s. This period came to be known as the Celtic Tiger and was focused on as a model for economic development in the former Eastern Bloc states, which entered the European Union in the early 2000s. Property values had risen by a factor of between four and ten between 1993 and 2006, in part fuelling the boom.

Irish society also adopted relatively liberal social policies during this period. Divorce was legalised, homosexuality decriminalised, while abortion in limited cases was allowed by the Irish Supreme Court in the X Case legal judgement. Major scandals in the Roman Catholic Church, both sexual and financial, coincided with a widespread decline in religious practice, with weekly attendance at Roman Catholic Mass halving in twenty years. A series of tribunals set up from the 1990s have investigated alleged malpractices by politicians, the Catholic clergy, judges, hospitals and the Gardaí (police).

xxxx

- Main article: History of Northern Ireland; for events before 1900 see Ulster or History of Ireland.

8 May 2007 Home rule returned to Northern Ireland. DUP leader Ian Paisley and Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness took office as First Minister and Deputy First Minister, respectively [1].

Casualties of the “Troubles”

Main article: The Troubles

Bombings in Great Britain tended to have had more publicity, since attacks there were comparatively rare (in the context of the troubles); indeed 93 percent of killings happened in Northern Ireland. Republican paramilitaries have contributed to nearly 60 percent (2056) of these. Loyalists have killed nearly 28 percent (1020) while the security forces have killed just over 11 percent (362) with 9 percent percent of those attributed to the British Army.

Civilians account for the highest death toll at 53 percent or 1798 fatalities. Loyalist paramilitaries account for a higher proportion of civilian deaths, according to figures published in Malcolm Sutton’s book, “Bear in Mind These Dead: An Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland 1969 - 1993.” According to research undertaken by the CAIN organisation, based on Sutton's work, 85.6 percent (873) of Loyalist killings, 52.9 percent (190) by the security forces and 35.9 percent (738) of all killings by Republican paramilitaries took the lives of civilians between 1969 and 2001. The disparity of a relatively high civilian death toll yet low Republican percentage is explained by the fact that they also had a high combatants' death toll.

Republican paramilitaries account for a higher proportion of combatants killed (those within paramilitaries or the military) Again from Malcolm Sutton's research, Republicans killed 1318 combatants, the security forces killed 192 and the Loyalists killed 147. Both Republicans and Loyalists killed more of their own than each other, over twice as many for Loyalists and nearly four times as many for Republicans.

Eighty people, mainly civilians, have died without any organisation claiming responsibility. The British Army has also lost 14 soldiers to Loyalists while the security forces overall in the Republic have lost 10 to Republicans.

According to a submission by Marie Smyth to the Northern Ireland Commission on Victims, 40,000 people have also been injured, though she believes that to be a conservative figure.

Government and politics

Structure

As an administrative division of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was defined by the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, and has had its own form of devolved government in a similar manner to Scotland and Wales. The new legislature controlled housing, education, and policing, but had little fiscal autonomy and became increasingly reliant upon subsidies from the British government. The legislature consisted of a Senate and a House of Commons.

After the partition of Ireland in 1922, Northern Ireland continued to send representatives to the British House of Commons, the number of which over the years increased to 18. Those 18 seats in 2007 comprised 10 unionist, five republican (abstentionist), and three nationalists. Northern Ireland also elects delegates to the European Parliament (the legislative branch of the European Union).

Escalating violence meant that in March 1972 the British government of Edward Heath suspended the Belfast parliament and governed the region directly, attempts to introduce either a power-sharing executive or a new assembly failed.

On April 10, 1998, the Belfast Agreement (also known as the Good Friday Agreement) was signed, and endorsed in referenda by about 95 percent of Irish voters and 70 percent of Northern Irish voters.

The 108-member Northern Ireland Assembly established in Belfast in 1998 has an executive of both unionists (Protestants who support continued British rule of Northern Ireland) and nationalists (Catholics who support a united Ireland). The legislature selects a first minister and a deputy first minister, both of whom need the support of a majority of unionist and nationalist legislators. Moreover, legislation can be passed in the assembly only if it has the support of a minimum proportion of both unionist and nationalist members.

Westminster retained control of taxation, policing, and criminal justice.

In 2002 devolved power was suspended, and Northern Ireland was ruled from London. However, in 2007, the hard-line Roman Catholic Sinn Féin and the Protestant Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) reached a historic settlement to form a power-sharing government, thereby allowing the return of devolved power to Northern Ireland.

The Northern Ireland Assembly has 108 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) (in 2007 55 unionists, 28 republicans, 16 nationalists, nine others), which had its powers restored on 8 May 2007. The three seats in the European Parliament (comprised two unionist, one republican)

At the local level in 2007 there were 26 district councils –with proposals to reduce the number of councils to seven

As the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland is a constitutional monarchy there is no election for Head of State.

Northern Ireland's legal and administrative systems were adopted from those in place in pre-partition United Kingdom, and was developed by its government from 1922 until 1972. Thereafter, laws, administration and foreign affairs relating to Northern Ireland have been handled directly from Westminster.

Northern Ireland's legal system descends from the pre-1920 Irish legal system (as does the legal system of the Republic of Ireland), and is therefore based on common law. It is separate from the jurisdictions of England and Wales or Scotland.

Counties

Northern Ireland consists of six counties: Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry, and Tyrone. These counties are no longer used for local government purposes; instead there are 26 districts of Northern Ireland which have different geographical extents, even in the case of those named after the counties from which they derive their name. Fermanagh District Council most closely follows the borders of the county from which it takes its name. Coleraine Borough Council, on the other hand, derives its name from the town of Coleraine in County Londonderry.

Economy

The Northern Ireland economy is the smallest of the four economies making up the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland has traditionally had an industrial economy, most notably in shipbuilding, rope manufacture and textiles, but most heavy industry has since been replaced by services, primarily the public sector. Tourism also plays a big role in the local economy. More recently the economy has benefited from major investment by many large multi-national corporations into high tech industry. These large organisations are attracted by government subsidies and the highly skilled workforce in Northern Ireland.

Fiscally a part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland's official currency is the British pound sterling. Government revenue shares the United Kingdom's customs and excise, income, value-added, and capital gains taxes, as well as property taxes. At the end of the twentieth century, subsidies from the British Treasury accounted for about two-fifths of Northern Ireland's GDP.

Throughout the 1990s, the Northern Irish economy grew faster than did the economy of the rest of the UK, due in part to the rapid growth of the economy of the Republic of Ireland and the so-called 'peace dividend'. Growth slowed to the pace of the rest of the UK during the down-turn of the early years of the new millennium, but growth has since rebounded.

During The Troubles, Northern Ireland received little foreign investment. Many believe this to be the result of Northern Ireland's portrayal as a warzone in the media, by both British and International during this period.

Since the signing of Good Friday Agreement investment in Northern Ireland has increased significantly. Most investment has been focused in Belfast and several areas of the Greater Belfast area.

Agriculture in Northern Ireland is heavily mechanised, thanks to high labour costs and heavy capital investment, both from private investors and the European Union's Common Agricultural Policy. In 2000, agriculture accounted for 2.4% of economic output in Northern Ireland, compared to 1% in the United Kingdom as a whole.

Heavy industry is concentrated in and around Belfast, although other major towns and cities also have heavy manfufacturing areas. Machinery and equipment manufacturing, food processing, and textile and electronics manufacturing are the leading industries. Other industries such as papermaking, furniture manufacturing, aerospace and shipbuilding are also important, concentrated mostly in the eastern parts of Northern Ireland. Of these different industries, one of the most notable is that of Northern Ireland's fine linens, which is considered as one of the most well-known around Europe.

Engineering is the largest manufacturing sub-sector in Northern Ireland, particularly in the fields of aerospace and heavy machinery. Bombardier Aerospace, which builds business jets, short-range airliners and fire-fighting amphibious aircraft and also provides defence-related services, is the province's largest industrial employer, with 5400 workers at five sites in the Greater Belfast area.

As with all developed economies, services account for the majority of employment and output. Services account for almost 70 percent of economic output, and 78 percent of employees.

Despite the negative image of Northern Ireland held in many foreign countries, on account of the Troubles, tourism is an important part of the Northern Irish economy. In 2004, tourism revenue rose 7 percent to £325m, or over 1 percent of the local economy, on the back of a rise of 4 percent in total visits to 2.1-million in the year. The most popular tourist attractions include Belfast, Armagh, the Giant's Causeway, and Northern Ireland's many castles.

The public sector accounts for 63 percent of the economy of Northern Ireland, which is substantially higher than 43 percent of the United Kingdom as a whole. In total, the British government subvention totals £5000m, or 20 percent of Northern Ireland's economic output.

Most of Northern Ireland's trade is with other parts of the United Kingdom, and the republic of Ireland, which is its leading export market, as well as Germany, France, and the United States. Principal exports are textiles, transport equipment, and electrical and optical equipment.

Northern Ireland has the smallest economy of any of the twelve NUTS 1 regions of the United Kingdom, at €37.3bn, or about two-thirds of the size of the next smallest, North East England. However, this is partly because Northern Ireland has the smallest population; at $19,603 Northern Ireland has a greater GDP per capita than both North East England and Wales. As a part of the UK, Northern Ireland lacks an international GDP per capita rating, but would fall between Kuwait (38th) and Hungary (39th).

Unemployment in Northern Ireland has decreased substantially in recent years, and was in 2006 4.5 percent, which is amongst the lowest of the regions of the United Kingdom, down from a peak of 17.2 percent in 1986.

Northern Ireland has well-developed transport infrastructure, with a total of 15,420 miles (24,820km) of roads, considerably more than in the United Kingdom as a whole (1 km per 162 people). There are seven motorways in Northern Ireland, extending radially from Belfast, and connecting that city to Antrim, Dungannon, Lisburn, Newtownabbey, and Portadown. The Northern Irish rail network is notable as being both the only part of the United Kingdom's railroads operated by a state-owned company, Northern Ireland Railways, and the only substantial part that carries no freight traffic.

Northern Ireland has three civilian airports: Belfast City, Belfast International, and City of Derry. Major seaports in Northern Ireland include the Port of Belfast and the Port of Larne. The Port of Belfast is one of the chief ports of the British Isles, handling 17 million tonnes (16.7 million long tons) of goods in 2005, equivalent to two-thirds of Northern Ireland's seaborne trade.

Demographics

Much of the population of Northern Ireland, numbering 1,710,300 in 2004, identifies by ethnicity, religion, and political bent with one of two different ideologies — unionism or nationalism. Ulster Unionists are generally Protestants, most of whom belong to the Presbyterian Church in Ireland or the Church of Ireland, whose ancestors came from England to colonize the country in the nineteenth century and earlier, and who supported William of Orange when he took the throne of England from the Catholic James II. The Nationalists are native Irish who were ruled by Irish chiefs, are Roman Catholics who want Northern Ireland to be reunited with the Republic of Ireland. Not all Catholics support Nationalism, and not all Protestants support Unionism. Polls point to a preference among Protestants to remain a part of the UK (85 percent), while Catholic preferences are spread across a number of solutions to the constitutional question including remaining a part of the UK (25 percent), a united Ireland (50 percent), Northern Ireland becoming an independent state (9 percent), and "don't know" (14 percent).

Ethnicity

Northern Ireland has had constant population movement with parts of western Scotland. After the Tudor invasions and after the forced settlements, or plantations, of the early seventeenth century, two distinct and antagonistic groups — of indigenous Roman Catholic Irish and the immigrant Protestant English and Scots -— have molded Northern Ireland's development. The settlers dominated County Antrim, northern Down, the Lagan corridor toward Armagh, and other powerful minorities.

According to the 2001 United Kingdom census, the ethnic composition of Northern Ireland was: White 99.15 percent, Han Chinese 0.25 percent, mixed 0.20 percent, Irish Traveller 0.10 percent, Indian 0.09 percent, other ethnic group 0.08 percent, Pakistani 0.04 percent, black African 0.03 percent, other black 0.02 percent, black Caribbean 0.02 percent, Bangladeshi 0.01 percent, and other Asian 0.01 percent.

Citizenship and identity

People from Northern Ireland are British citizens on the same basis as people from any other part of the United Kingdom (e.g. by birth in the UK to at least one parent who is a UK permanent resident or citizen, or by naturalisation).

In addition to British citizenship, people who were born in Northern Ireland on or before 31 December 2004 (and most persons born after this date) are entitled to claim Irish citizenship. This is as a result of the Republic of Ireland extending Irish nationality law on an extra-territorial basis. Originally passed in 1956, the legislation was further developed in 2001 as a result of the Belfast Agreement of 1998, which stated that:

This was subsequently qualified by the Twenty-seventh Amendment]] of the Constitution of Ireland, which required citizenship claimants to have at least one parent who was (or was entitled to be) an Irish citizen. The subsequent legislation (Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act of 2004) came into effect on 1 January 2005 and brought Irish nationality law broadly into line with British nationality law.

Today, a constitutional right to Irish citizenship still exists for anyone who is both:

- Born on the island of Ireland (including its "isles and seas").

- Born to at least one parent who is, or is entitled to be, an Irish citizen.

In general, Protestants in Northern Ireland see themselves primarily as being British citizens, while Catholics regard themselves primarily as being Irish citizens.

Many of the population regard themselves as "Ulster" or "Northern Irish," either primarily, or as a secondary identity. In addition, many regard themselves as both British and Irish.

Not everyone in Northern Ireland regards themselves as being Irish, particularly not Protestants. A 1999 survey showed that 51% of Protestants felt "Not at all Irish" and 41% only "weakly Irish."

Religion

Most of the population of Northern Ireland are at least nominally Christian. In the 2001 census, 53.1 percent of the Northern Irish population were Protestant, (Presbyterian, Church of Ireland, Methodist and other Protestant denominations), 43.8 percent of the population were Roman Catholic, 0.4 percent Other and 2.7 none none.

The demographic balance between Protestants and Roman Catholics has become delicate, since the slightly higher birth rate of Catholics has led to speculation that they will outnumber Protestants. During the political violence of the last 30 years of the twentieth century, many Protestants moved away from western and border areas, giving Londonderry, Fermanagh, and Tyrone marked Catholic majorities. The traditional concentration of Protestants in the east increased, except in Belfast, where Catholics have become the majority.

Presbyterians were the most substantial Protestant denomination in 2001, with 20.7 percent of the population, while the Anglican Church of Ireland had 15.3 percent. The remainder of the Protestant population is fragmented among dozens of smaller religious groupings.

The proportion of the population practising their religious beliefs has fallen dramatically in the last decades of the twentieth century, particularly among Catholics and adherents of mainstream Protestant denominations. This has not necessarily resulted in a weakening of communal feeling.

Language

The influx of English and Scottish colonists contributed to the decline of spoken Irish (Gaelic). English is spoken as a first language by almost 100 percent of the Northern Irish population, though under the Good Friday Agreement, Irish and Ulster Scots (one of the dialects of the Scots language), sometimes known as Ullans, have recognition as "part of the cultural wealth of Northern Ireland".

Northern Ireland's political divisions are partly reflected through language. Irish is spoken by a small but significant and growing proportion of the population and is an important element of the cultural identity for many northern nationalists. Unionists tend to associated the use of Irish it with the largely Catholic Republic of Ireland, and more recently, with the republican movement. Catholic areas of Belfast have road signs in Irish, as they are in the Republic.

Northern Irish people speak English with distinctive regional accents. The northeastern dialect, of Antrim and Londonderry and parts of Down, derives from the central Scottish dialect. The remaining area, including the Lagan valley, has English accents from England, Cheshire, Merseyside, Greater Manchester, and southern Lancashire.

There are an increasing number of Ethnic Minorities in Northern Ireland. Chinese and Urdu are spoken by Northern Ireland's Asian communities; though the Chinese community is often referred to as the "third largest" community in Northern Ireland, it is tiny by international standards. Since the accession of new member states to the European Union in 2004, Central and Eastern European languages, particularly Polish, are becoming increasingly common.

Men and women

In 1937, the constitution required that a working woman who married had to resign from her job. The Employment Equality Act in 1977 made that practice illegal, resulting in a dramatic increase in women in the work force. More women entering the workforce between 1952 and 1995 as the number of jobs expanded. However, women tend to work in low-paid, part-time jobs in the service sector.

Marriage and the family

Families have tended to live in nuclear units in government housing projects in separate Catholic and Protestant areas — like the Falls Road (Catholic) and the Shankill (Protestant) areas in Belfast. Catholics tend to have larger families, making their homes more crowded. Nuclear families are the main kin group, with relatives involved as kin in the extended family. Children adopt the father's surname, and the first name is oftena Christian name.

Education

Education in Northern Ireland differs slightly from systems used elsewhere in the United Kingdom. The Northern Ireland system emphasises a greater depth of education compared to the English and Welsh systems. A child's age on the July 1 determines the point of entry into the relevant stage of education unlike Great Britain where it is the September 1. Northern Ireland's results at GCSE and A-Level are consistently top in the UK. At A-Level, one third of students in Northern achieved A grades in 2007, compared to one quarter in England and Wales.

All schools in Northern Ireland follow the Northern Ireland Curriculum which is based on the National Curriculum used in England and Wales. At age 11, on entering secondary education, all pupils study a broad base of subjects which include Geography, English, Mathematics, Science, PE, Music and modern languages.

Primary education extends from age 4 to 11, when pupils sit the Eleven plus test, and the results determine which school they will go to.

- Secondary education

- Secondary School or Grammar School

- Key Stage 3

- Year 8, age 11 to 12 (equivalent to Year 7 in England and Wales)

- Year 9, age 12 to 13

- Year 10, age 13 to 14

- Key Stage 4

- Year 11, age 14 to 15

- Year 12, age 15 to 16 (GCSE examinations)

- Key Stage 3

- Secondary School, Grammar School, or Further Education College

- Sixth form

- Year 13, age 16 to 17 (AS-level examinations)

- Year 14, age 17 to 18 (A-levels (A2))

- Sixth form

- Secondary School or Grammar School

Although religious Integrated Education is increasing, Northern Ireland has a highly segregated education system, with 95% of pupils attending either a maintained (Catholic) school or a controlled school (mostly Protestant). However, controlled schools are open to children of all faiths and none. Teaching a balanced view of some subjects (especially regional history) is difficult in these conditions. The Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education (NICIE), a voluntary organisation, promotes, develops and supports Integrated Education in Northern Ireland.

School holidays in Northern Ireland are considerably different from the rest of the United Kingdom, and are more similar to those in the Republic of Ireland. Northern Irish schools often do not take a full week for half term holidays, and the Summer term does not usually have a half term at all. Christmas holidays sometimes consist of less than two weeks, the same with the Easter holiday. This does, however, vary considerably between schools. The major difference however is that summer holidays are considerably longer with the entirety of July and nearly all of August off, giving an eight week summer holiday.

See:

- List of Gaelic medium Primary schools in Northern Ireland

- List of Primary schools in Northern Ireland

- List of Grammar schools in Northern Ireland

- List of Secondary schools in Northern Ireland

- List of Integrated Schools in Northern Ireland

Class

Catholics were excluded from skilled and semiskilled jobs in shipyards and linen mills, were restricted to menial jobs, earning lower wages, and tended to be poorer than Protestants. Protestants worked in skilled jobs and management positions, dominated the professional and business classes, and tend to own most businesses and large farms.

Protestant and Catholic families lived in separate enclaves and worship separately, and their children study in segregated schools.

Irish Catholics tend to drink liquor, whereas Protestants are viewed as more puritanical. On Sundays, Catholics often engage in leisure or recreation activities after mass. They tend to be poorer, have larger families, speak Gaelic, although not fluently.

Protestants tend to belong to the Orange Order, which is dedicated to maintaining the Protestant religion and Protestant social superiority.

Unionist/Loyalist

- Ulster - this is used by some to suggest that the border of the province of Ulster, one of four provinces on the island of Ireland, was redrawn due to partition. The historic province of Ulster covers a greater landmass than Northern Ireland: six of its counties are in Northern Ireland, three in the Republic of Ireland.[2]

- The Province - to again link to the historic Irish province of Ulster, with its mythology. Also refers to the fact that NI is a province of the UK.[3]

Nationalist/Republican

- North of Ireland (Tuaisceart na hÉireann) - to link Northern Ireland to the rest of the island, by describing it as being in the 'north of Ireland' and so by implication playing down Northern Ireland's links with Great Britain. (The northernmost point in Ireland, in County Donegal, is in fact in the Republic.)[4]

- North-East Ireland - used in the same way as the "North of Ireland" is used.

- The Six Counties (na Sé Chontae) - language used by republicans e.g. Republican Sinn Féin, which avoids using the name given by the British-enacted Government of Ireland Act, 1920. (The Republic is similarly described as the Twenty-Six Counties.)[5] Some of the users of these terms contend that using the official name of the region would imply acceptance of the legitimacy of the Government of Ireland Act.

- The Occupied Six Counties. The Republic, whose legitimacy is not recognised by republicans opposed to the Belfast Agreement, is described as being "The Free State," referring to the Irish Free State, the Republic's old name.[6]

- British-Occupied Ireland. Similar in tone to the Occupied Six Counties this term is used by more dogmatic anti-Good Friday Agreement republicans who still hold that the First Dáil was the last legitimate government of Ireland and that all governments since have been foreign imposed usurpations of Irish national self-determination.[7]

- Fourth Green Field. From the song Four Green Fields by Tommy Makem which describes Ireland as divided with one of the four green fields (the traditional provinces of Ireland) being In strangers hands, referring to the partition of Ireland.

Other