| European Union |

This article is part of the series: |

|

|

| Treaties |

|---|

| Rome · Maastricht (Pillars) Amsterdam · Nice · Reform |

| Institutions |

| Commission

President José Manuel Barroso |

| Parliament

President Hans-Gert Pöttering |

| Council

Presidency: Portugal (Luís Amado) |

| Court of Justice

President · Members First Instance |

| Elections |

| Last election (2004) · 2007 by-election Next election (2009) · Constituencies Parties · Parliamentary groups |

| Related topics |

| States · Enlargement · Foreign relations Law · EMU · Other bodies · Agencies |

The European Community (EC) was originally founded on March 25, 1957, by the signing of the Treaty of Rome under the name of European Economic Community. The "Economic" was removed from its name by the Maastricht treaty in 1992, which at the same time effectively made the European Community the first of three pillars of the European Union, called the Community (or Communities) Pillar. The founders of the community believed that closer relations between European states, improved trade and access to resources, and the development of supranational loyalties to a larger entity, would help to make war in Europe unthinkable. Since the founding of the original, trade based Community, what is now referred to as the European Union has evolved. Members practice the principle of subsidiarity; that is, that functions should be handled at an appropriate level, be it local, regional, national, or continental. In many areas, such as employment and human rights, members have brought their national law into conformity. Borders have been relaxed and members can work throughout the Union. Passports bear the imprint of the European Union in addition to that of the issuing state.

While the founders' hopes for supranational identity and for stronger institutions have not yet fully materialized, many do regard themselves as truly European citizens, while also remaining citizens of their home states.

Origins

In the aftermath of World War II, several people proposed that an organization that bound European states together would help to prevent war from happening again. One of the architects of what emerged as the European Union was Robert Schuman, who proposed an Assembly for Europe and a democratic organization in a speech at the United Nations in September 1948. On May 9, 1950, his ideas were published as the Schuman Declaration, a central concern of which was the promotion of free-trade and resolution of issues surrounding access to necessary resources. The latter had been a cause of conflict in the past. Pooling of French and German coal production was one of the main proposals. Also involved in these proposals was another architect of post-World War II European Unity, Jean Monnet. Winston Churchill, although his nation at this time remained outside these developments in Europe, had also spoken of the desirability of some type of European community, arguing that, as a result of Western European unity, the nations of the East would also eventually gain their independence. As early as 1945, Churchill proposed a United States of Europe, "to promote harmonious relations between nations, economic cooperation, and a sense of European identity."[1] Schuman spoke of supranational democracy as the eventual goal of the new European project.

Community pillar

The Maastricht treaty turned the European Communities as a whole into the first of three pillars of the European Union, also known as the Community Pillar or Communities Pillar. In Community Pillar policy areas, decisions are made collectively by Qualified Majority Voting (QMV).

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was an organization established by the Treaty of Rome (March 25, 1957) between the ECSC countries Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany, known informally as the Common Market (the Six). The EEC was the most significant of the three treaty organizations that were consolidated, in 1967, to form the European Community (EC; known since the ratification in 1993, of the Maastricht treaty as the European Union, EU). The EEC had as its aim the eventual economic union of its member nations, ultimately leading to political union. It worked for the free movement of goods, service, labor, and capital, the abolition of trusts and cartels, and the development of joint and reciprocal policies on labor, social welfare, agriculture, transport, and foreign trade.

In 1956, the United Kingdom proposed that the Common Market be incorporated into a wide, European free-trade area. After the proposal was vetoed by President Charles de Gaulle and France in November 1958, the UK, together with Sweden, engineered the formation (1960) of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and was joined by other European nations that did not belong to the Common Market (the Seven). Beginning in 1973, with British, Irish, and Danish accession to the EEC, the EFTA, and the EEC, negotiated a series of agreements that would ensure uniformity between the two organizations in many areas of economic policy, and by 1995, all but four EFTA members had joined the European Union.

One of the first important accomplishments of the EEC was the establishment (1962) of common price levels for agricultural products. In 1968, internal tariffs (tariffs on trade between member nations) were removed on certain products.

The future of the European Communities

The signed but unratified European Constitution would merge the European Community with the other two pillars of the European Union, making the European Union the legal successor of both the European Community and the present-day European Union. It was, for a time, proposed that the European Constitution should repeal the Euratom treaty, in order to terminate the legal personality of Euratom at the same time as that of the European Community, but this was not included in the final version. The proposed constitution raised, for many, questions about identity and belonging and issues of sovereignty. The idea of the nation state as an almost sacred political institution, post Westphalia, is for many such a deep rooted notion that the idea of supranationality envisaged by Schuman and some of the founders of the European Union seems dangerous.

Proposals for shared foreign polity, even for a common defense policy, frightens some. The choice of some member states to stay outside the common currency, the Euro, was less economical than patriotic. To date, it can be said that the original vision of the founders of the Union in terms of making war unthinkable in Europe has proved to be true. The EU, says Kleiman, "makes intra-European war unthinkable; it makes the establishment of tyranny in any European country impossible; and (despite its current economic troubles) it has spread prosperity to its poorer members."[2] However, the vision of transcending the nation state has so far floundered.

Debate on identity

During discussion on the proposed Constitution, some wanted specific mention of Europe's Christian heritage. This angered others, who pointed out that Europe's secular-humanist heritage had also done much to shape its culture. Others pointed out that Jews had long contributed to Europe. Still others pointed out that Muslims had made very significant contributions, for example, through Moorish Spain. As Turkey's application for membership has been discussed, some politicians have expressed the view that as a majority Muslim state, and there has been widespread talk of Europe as a "Christian Club," with no room for Turkey.[3]

Draft articles published in February 2006, made reference to member countries' national identities, to human rights, to shared commitment to social justice, and the to the environment. However, there was no mention of God or of a Christian heritage.[4] On the other hand, religious freedom is enshrined in EU law.

The delayed membership of certain East European states, which are majority Orthodox Christian and whose cultures share comparatively little in common with the Catholic and Protestant West of Europe, has also been attributed to cultural preconceptions. Apostolov comments that:

the Western Christians of the Czeck Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovenia, Malta and the three Baltic states were easily accepted, while any "Orthodox" completion of the Union has always been regarded with suspicion, and endorsed for primarily strategic reasons. The European Union accepted Greece in 1981, for instance, in order to bolster its young democratic institutions and reinforce the strategic southern flank against the communist bloc. Yet diplomatic gossips in Brussels targeted, for years, the inclusion of Greece as an anomalous member who received much, and contributed little.[5]

Occupying what is often called former Ottoman space, the Balkan states have been described as less European than as a buffer zone, a half-way house, between Europe and the Muslim world.

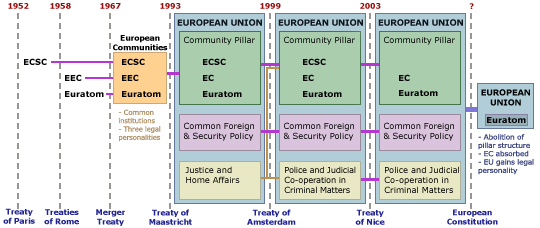

Timeline

Evolution of the Structures of European Union

| 1951 | 1957 | 1965 | 1992 | 1997 | 2001 | 2009 ? |

| European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) | ||||||

| Euratom (European Atomic Energy Community) | ||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) |

European Community (EC) | |||||

| ...European Communities: ECSC, EEC (EC, 1993), Euratom | Justice & Home Affairs |

| ||||

| Police & Judicial Co-operation in Criminal matters (PJCC) | ||||||

| Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) | ||||||

| E U R O P E A N   U N I O N   ( E U ) | ||||||

| Treaty of Paris | Treaties of Rome | Merger Treaty | Treaty of Maastricht | Treaty of Amsterdam | Treaty of Nice | Reform Treaty |

|

"THREE PILLARS" - ECs (ECSC, EEC/EC, Euratom), CFSP, PJCC |

||||||

The European Community within the Union

The term "European Communities" refers collectively to two entities‚ÄĒthe European Economic Community (now called the European Community) and the European Atomic Energy Community (also known as Euratom)‚ÄĒeach founded pursuant to a separate treaty in the 1950s. A third entity, the European Coal and Steel Community, was also part of the European Communities, but ceased to exist in 2002, upon the expiration of its founding treaty. Since 1967, the European Communities have shared common institutions, specifically the Council, the European Parliament, the Commission, and the Court of Justice. In 1992, the European Economic Community, which of the three original communities had the broadest scope, was renamed the "European Community" by the Treaty of Maastricht.

The European Communities are one of the three pillars of the European Union, being both the most important pillar and the only one to operate primarily through supranational institutions. The other two "pillars"‚ÄĒCommon Foreign and Security Policy, and Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters‚ÄĒre looser intergovernmental groupings. Confusingly, these latter two concepts are increasingly administered by the Community (as they are built up from mere concepts to actual practice).

If it had been ratified, the proposed new Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe would have abolished the three-pillar structure and, with it, the distinction between the European Union and the European Community, bringing all the Community's activities under the auspices of the European Union and transferring the Community's legal personality to the Union. There is, however, one qualification: It appears that Euratom would remain a distinct entity governed by a separate treaty (because of the strong controversy the issue of nuclear energy causes, and Euratom's relative unimportance, it was considered expedient to leave Euratom alone in the process of EU constitutional reform).

| Evolution of the structures of the European Union. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Treaties, structure and history of the European Union

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ The Churchill Center, Churchill and the Unification of Europe. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Mark Kleiman, The Case for Europe.

- ‚ÜĎ BBC, Turkey entry would 'destroy' EU. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Free Republic, European Christians Unhappy with Ommission in EU Constitution. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Apostolov (2004), p 129.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Apostolov, Mario. The Christian-Muslim Frontier A Zone of Contact, Conflict, or Cooperation. London: Routledge Curzon, 2004. ISBN 978-0415302814

- Dinan, Desmond. Europe Recast: A History of European Union. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2004. ISBN 978-1588262059

- Moussis, Nicolas. Access to European Union: Law, Economics, Policies. Genval [Belgium]: Euroconfidentiel, 1997. ISBN 978-2930066394

- Nugent, Neill. The Government and Politics of the European Union. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0822315063

- Peterson, John and Michael Shackleton. The Institutions of the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0199574988

- Rifkin, Jeremy. The European Dream: How Europe's Vision of the Future is Quietly Eclipsing the American Dream. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2004. ISBN 978-1585423453

External links

All links retrieved March 23, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.