Boar

| Wild Boar | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Sus scrofa Linnaeus, 1758 |

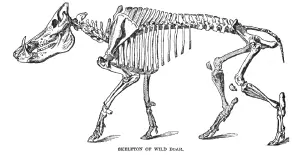

Boar, or wild boar, is an omnivorous, gregarious mammal, Sus scrofa of the biological family Suidae, characterized by large heads with tusks and a distinctive snout with a disk-shaped nose, short necks, relatively small eyes, prominent ears, and a coat that has dense, dark bristles. This wild species is the ancestor of the domestic pig, Sus scrofa domesticus,which was one of the first domesticated animals (Seward 2007).

The boar is native across much of Central Europe, the Mediterranean Region (including North Africa's Atlas Mountains) and much of Asia as far south as Indonesia, and has been introduced elsewhere. Although common in France, the wild boar became extinct in Great Britain and Ireland by the 17th century, but wild breeding populations have recently returned in some areas, following escapes from boar farms (Goulding and Smith 1998).

The term boar also is used more generally to denote an adult male of certain species—including, confusingly, domestic pigs. However, for the wild boar, the term applies to the whole species, including, for instance, "sow wild boar" (female wild boar) or "wild boar piglet." The term also is used for the males of certain mammals, such as the guinea pig, badger, skunk, raccoon, and mink.

Physical characteristics

The body of the wild boar is compact; the head is large, the legs relatively short. The fur consists of stiff bristles and usually finer fur. The colour usually varies from dark grey to black or brown, but there are great regional differences in colour; even whitish animals are known from central Asia.[1] During winter the fur is much denser.

Adult boars average 100-150 cm in length and have a shoulder height of 90 cm.[2] As a whole, their average weight is 60-70 kilograms (132-154 pounds), though boars show a great deal of weight variation within their geographical ranges. Boars shot in Tuscany have been recorded to weigh 150 kg (331 lbs). A French specimen shot in Negremont forest in Ardenne in 1999 weighed 227 kg (550 lbs). Carpathian boars have been recorded to reach weights of 200 kg (441 lbs), while Romanian and Russian boars can reach weights of 300 kg (661 lbs).[2] Boars even approaching this size today are considered exceptional.[citation needed]

The continuously growing tusks (the canine teeth) serve as weapons and burrowing tools. The lower tusks of an adult male measure about 20 cm (7.9 in) (from which seldom more than 10 cm (3.9 in) protrude out of the mouth), in exceptional cases even 30 cm (12 in). The upper tusks are bent upwards in males, and are regularly ground against each other to produce sharp edges. In females they are smaller, and the upper tusks are only slightly bent upwards in older individuals.

Wild boar piglets are coloured differently from adults, being a soft brown with longitudinal darker stripes. The stripes fade by the time the piglet is about half-grown, when the animal takes on the adult's grizzled grey or brown colour.

Behavior

Wild boars live in groups called sounders. Sounders typically contain around 20 animals, but groups of over 50 have been seen. In a typical sounder there are two or three sows and their offspring; adult males are not part of the sounder outside of a breeding cycle, two to three per year, and are usually found alone. Birth, called farrowing, usually occurs in a secluded area away from the sounder; a litter will typically contain 8-12 piglets.[3](p. 6) The animals are usually nocturnal, foraging from dusk until dawn but with resting periods during both night and day.[3](p. 4-5, 8-9) They eat almost anything they come across, including grass, nuts, berries, carrion, roots, tubers, refuse, insects, small reptiles—even young deer and lambs.[3](p. 9-10)

Boars are the only hoofed animals known to dig burrows, a habit which can be explained by the fact that they are the only known mammals lacking brown adipose tissue. Therefore, they need to find other ways to protect themselves from the cold. For the same reason, piglets often shiver to produce heat themselves.[4]

If surprised or cornered, a boar (and particularly a sow with her piglets) can and will defend itself and its young with intense vigor. The male lowers its head, charges, and then slashes upward with its tusks. The female, which is tuskless, charges with its head up, mouth wide, and bites. Such attacks are not often fatal to humans, but severe trauma, dismemberment, and blood loss can very easily result.

Range

Reconstructed range

The wild boar was originally found in North Africa and much of Eurasia from the British Isles to Japan and the Sunda Islands. In the north it reached southern Scandinavia and southern Siberia. Within this range it was absent in extremely dry deserts and alpine zones.

A few centuries ago it was found in North Africa along the Nile valley up to Khartum and north of the Sahara. The reconstructed northern boundary of the range in Asia ran from Lake Ladoga (at 60°N) through the area of Novgorod and Moscow into the southern Ural, where it reached 52°N. From there the boundary passed Ishim and farther east the Irtysh at 56°N. In the eastern Baraba steppe (near Novosibirsk) the boundary turned steep south, encircled the Altai Mountains, and went again eastward including the Tannu-Ola Mountains and Lake Baikal. From here the boundary went slightly north of the Amur River eastward to its lower reaches at the China Sea. At Sachalin there are only fossil reports of wild boar. The southern boundaries in Europe and Asia were almost everywhere identical to the sea shores of these continents. In dry deserts and high mountain ranges, the wild boar is naturally absent. So it is absent in the dry regions of Mongolia from 44-46°N southward, in China westward of Sichuan and in India north of the Himalaya. In high altitudes of Pamir and Tien Shan they are also absent; however, at Tarim basin and on the lower slopes of the Tien Shan they do occur.[1]

Present range

In recent centuries, the range of wild boar changed dramatically because of hunting by humans. They probably became extinct in Great Britain in the 13th century: certainly none remained in southern England by 1610, when King James I reintroduced them to Windsor Great Park. This attempt failed due to poaching, and later attempts met the same fate. By 1700 there were no wild boar remaining in Britain.

In Denmark the last boar was shot at the beginning of the 19th century, and in 1900 they were absent in Tunisia and Sudan and large areas of Germany, Austria and Italy. In Russia they were extinct in wide areas in the 1930s, and the northern boundary has shifted far to the south, especially in the parts to the west of the Altai Mountains.

By contrast, a strong and growing population of boar has remained in France, where they are hunted for food and sport, especially in the rural central and southern parts of that country.

By 1950 wild boar had once again reached their original northern boundary in many parts of their Asiatic range. By 1960 they reached Saint Petersburg and Moscow, and by 1975 they were to be found in Archangelsk and Astrakhan. In the 1970s they again occurred in Denmark and Sweden, where captive animals escaped and survive in the wild. In the 1990s they migrated into Tuscany in Italy.

Status in Britain

Between then and the 1980s, when wild boar farming began, only a handful of captive wild boar, imported from the continent, were present in Britain. Because wild boar are included in the Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976, certain legal requirements have to be met prior to setting up a farm. A licence to keep boar is required from the local council, who will appoint a specialist to inspect the premises and report back to the council. Requirements include secure accommodation and fencing, correct drainage, temperature, lighting, hygiene, ventilation and insurance. Occasional escapes of wild boar have occurred since the 1970s. Early escapes occurred from Wildlife Parks, but since the early 1990s more escapes have been from farms, the number of which has increased as the demand for wild boar meat has grown. By the 1990s, a breeding population was rumoured to have established in areas of Kent and East Sussex. In 1998, a MAFF (now DEFRA) study on wild boar living wild in Britain confirmed the presence of two populations of wild boar living in Britain, one in Kent and East Sussex and another in Dorset.[3]

Subspecies

The wild boar is divided into over 11 different subspecies, of which six are present in Europe.[2]

- Sus scrofa scrofa: The most common and most widespread subspecies, its original distribution ranges from France to European Russia. It has been introduced in Sweden, Norway, the USA and Canada.[2]

- Sus scrofa baeticus: A small subspecies present in the Iberian Peninsula.[2]

- Sus scrofa castilianus: Larger than baeticus, it inhabits northern Spain.[2]

- Sus scrofa meridionalis: A small subspecies present in Sardinia.[2]

- Sus scrofa majori: A subspecies smaller than scrofa with a higher and wider skull. It occurs in central and southern Italy. Since the 1950s, it has hybridized extensively with introduced scrofa populations.[2]

- Sus scrofa attila: A very large subspecies ranging from Romania, Hungary, in Transylvania and in the Caucuses up to the Caspian Sea. It is thought that boars present in Ukraine, Asia Minor and Iran are part of this subspecies.[2]

- Sus scrofa ussuricus (northern Asia and Japan)

- Sus scrofa cristatus (Asia Minor, India)

- Sus scrofa vittatus (Indonesia)

- Sus scrofa taivanus (Formosan Wild Boar 台灣野豬(山豬))[5] (Taiwan)

The domestic pig is usually regarded as a further subspecies, Sus scrofa domestica – but sometimes as a separate species, Sus domestica. Different subspecies can usually be distinguished by the relative lengths and shapes of their lacrimal bones. S. scrofa cristatus and S. scrofa vittatus have shorter lacrimal bones than European subspecies.[6] Spanish and French boar specimens have 36 chromosomes, as opposed to wild boar in the rest of Europe which possess 38, the same number as domestic pigs. Boars with 36 chromosomes have successfully mated with animals possessing 38, resulting in fertile offspring with 37 chromosomes.[7]

Feral pigs

Domestic pigs quite readily become feral, and feral populations often revert to a similar appearance to wild boar; they can then be difficult to distinguish from natural or introduced true wild boar (with which they also readily interbreed). The characterization of populations as feral pig, escaped domestic pig or wild boar is usually decided by where the animals are encountered and what is known of their history. In New Zealand, for example, feral pigs are known as "Captain Cookers" from their supposed descent from liberations and gifts to Māori by explorer Captain James Cook in the 1770s.[8] New Zealand feral pigs are also frequently known as "tuskers", due to their appearance.

One characteristic by which domestic and feral animals are differentiated is their coats. Feral animals almost always have thick, bristly coats ranging in colour from brown through grey to black. A prominent ridge of hair matching the spine is also common, giving rise to the name razorback in the southern United States, where they are common. The tail is usually long and straight. Feral animals tend also to have longer legs than domestic breeds and a longer and narrower head and snout.

A very large swine dubbed Hogzilla was shot in Georgia, USA in June 2004.[9] Initially thought to be a hoax, the story became something of an internet sensation. National Geographic Explorer investigated the story, sending scientists into the field. After exhuming the animal and performing DNA testing, it was determined that Hogzilla was a hybrid of wild boar and domestic swine.[10]

At the beginning of the 20th century, wild boar were introduced for hunting in the United States, where they interbred in parts with free roaming domestic pigs. In South America, New Guinea, New Zealand, Australia and other islands, wild boar have also been introduced by humans and have partially interbred with domestic pigs.

In South America, also during the early 20th century, free-ranging boars were introduced in Uruguay for hunting purposes and eventually crossed the border into Brazil sometime during the 1990s, quickly becoming an invasive species, licensed private hunting of both feral boars and hybrids (javaporcos) being allowed from August 2005 on in the Southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul[11], although their presence as a pest had been already noticed by the press as early as 1994[12] . Releases and escapes from unlicensed farms (established because of increased demand for boar meat as an alternative to pork), however, continued to bolster feral populations and by mid-2008 licensed hunts had to expanded to the states of Santa Catarina and São Paulo[13].

It must be kept in mind that those recently established Brazilian boar populations are not to be confused with long establlished populations of feral pigs (porcos monteiros), which have existed mainly in the Pantanal for more than a hundred years, along with native peccaries. The demographic dynamics of the interaction between feral pigs populations and those of the two native species of peccaries (Collared Peccary and White-lipped Peccary) is obscure and is being studied presently. It has been proposed that the existence of feral pigs could somewhat ease jaguar predation on peccary populations, as jaguars would show a preference for hunting pigs, when these are available[14].

As of 2008, the estimated population of 4 million feral hogs cause an estimated US$800 million of property damage a year in the U.S.[15]

Natural predators

Wild boar are preyed upon by tigers in the regions where they coexist.[16]

Wolves are also major predators of boars in some areas. Wolves mostly feed on piglets, though adults have been recorded to be taken in Italy, the Iberian Peninsula and Russia. Wolves rarely attack boars head on, preferring to tear at their perineum, causing loss of coordination and massive blood loss. In some areas of the former Soviet Union, a single wolf pack can consume an average to 50-80 wild boars annually.[17] In areas of Italy where the two animals are sympatric, the extent to which boars are preyed upon by wolves has led to them developing more aggressive behaviour toward both wolves and domestic dogs.[2]

Striped hyenas occasionally feed on boars, though it has been suggested that only hyenas from the three larger subspecies present in Northwest Africa, the Middle East and India can successfully kill them.[18]

Commercial use

The hair of the boar was often used for the production of the toothbrush until the invention of synthetic materials in the 1930s.[19] The hair for the bristles usually came from the neck area of the boar. While such brushes were popular because the bristles were soft, this was not the best material for oral hygiene as the hairs were slow to dry and usually retained bacteria. Today's toothbrushes are made with plastic bristles.

Boar hair is used in the manufacture of boar-bristle hairbrushes, which are considered to be gentler on hair—and much more expensive—than common plastic-bristle hairbrushes.

Boar hair is used in the manufacture of paintbrushes, especially those used for oil painting. Boar bristle paintbrushes are stiff enough to spread thick paint well, and the naturally split or "flagged" tip of the untrimmed bristle helps hold more paint.

Despite claims that boar bristles have been used in the manufacture of premium dart boards for use with steel-tipped darts, these boards are, in fact, made of other materials and fibers – the finest ones from sisal rope.

In many countries, boar are farmed for their meat, and in countries such as France, for example, boar (sanglier) may often be found for sale in butcher shops or offered in restaurants (although the consumption of wild boar meat has been linked to transmission of Hepatitis E in Japan).[20]

Mythology, fiction and religion

In Greek mythology, two boars are particularly well known. The Erymanthian Boar was hunted by Heracles as one of his Twelve Labours, and the Calydonian Boar was hunted in the Calydonian Hunt by dozens of other mythological heroes, including some of the Argonauts and the huntress Atalanta.

In Celtic mythology the boar was sacred to the goddess Arduinna,[21][22] and boar hunting features in several stories of Celtic and Irish mythology. One such story is that of how Fionn mac Cumhaill ("Finn McCool") lured his rival Diarmuid Ua Duibhne to his death - gored by a wild boar.

Ares, the Greek god of war, had the ability to transform himself into a wild boar, and even gored his son to death in this form to prevent the young man from growing too attractive and stealing his wife, similar to Oedipus marrying his own mother.

The Norse gods Freyr and Freyja both had boars. Freyr's boar was named Gullinbursti ("Golden Mane"), who was manufactured by the dwarf Sindri due to a bet between Sindri's brother Brokkr and Loki. The bristles in Gullinbursti's mane glowed in the dark to illuminate the way for his owner. Freya rode the boar Hildesvini (Battle Swine) when she was not using her cat-drawn chariot. According to the poem Hyndluljóð, Freyja concealed the identity of her protégé Óttar by turning him into a boar. In Norse mythology, the boar was generally associated with fertility.

In Persia (Iran) during the Sassanid Empire, boars were respected as fierce and brave creatures, and the adjective "Boraz (Goraz)" (meaning boar) was sometimes added to a person's name to show his bravery and courage. The famous Sassanid spahbod, Shahrbaraz, who conquered Egypt and the Levant, had his name derived Shahr(city) + Baraz(boar like/brave) meaning "Boar of the City".[citation needed]

In Hindu mythology, the third avatar of the Lord Vishnu was Varaha, a boar.

In Chinese horoscope the boar (sometimes also translated as pig), is one of the twelve animals of the zodiac, based on the legends about its creation, either involving Buddha or the Jade Emperor.[citation needed]

In the Asterix comic series, wild boar are the favourite food of Obelix whose immense appetite means that he can eat several roasted boar in a single sitting.

Heraldry and other symbolic use

The wild boar and a boar's head are common charges in heraldry. It represents what are often seen as the positive qualities of the boar, namely courage and fierceness in battle.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 V. G. Heptner and A. A. Sludskii: Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. II, Part 2 Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats). Leiden, New York, 1989 ISBN 900408876 8 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "mammals of the soviet union" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 (Italian)Scheggi, Massimo (1999). La Bestia Nera: Caccia al Cinghiale fra Mito, Storia e Attualità, pp.201. ISBN 8825379048.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameddfra - ↑ Catherine Scullion. Shiver Me Piglets!. null-hypothesis.co.uk. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ Wow, Taipei Zoo! 臺北動物園全球資訊網

- ↑ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1987). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals, pp.208. ISBN 0521346975.

- ↑ Wild boar profile

- ↑ Horwitz, Tony (2003). Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before. Picador, 127. ISBN 0312422601.

- ↑ Dewan, Shaila, "DNA tests to reveal if possible record-size boar is a pig in a poke", 'San Francisco Chronicle', 2005-03-19. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ "The Mystery of Hogzilla Solved", ABC News, 2005-03-21. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ↑ www.institutohorus.org.br/download/marcos_legais/INSTRUCAO_NORMATIVA_N_71_04_agosto_2005.pdf

- ↑ "Javali: fronteiras rompidas" ("Boars break across the border") Globo Rural 9:99, January 1994, ISSN 0102-6178, pgs.32/35

- ↑ /www.arroiogrande.com/especiais_javali.htm

- ↑ www.cienciahoje.uol.com.br/controlPanel/materia/view/3835

- ↑ Brick, Michael (2008-06-21). Bacon a Hard Way: Hog-Tying 400 Pounds of Fury. The New York Times.

- ↑ Yudakov, A. G. and I. G. Nikolaev, The Ecology of the Amur Tiger [Chapter 13]

- ↑ Graves, Will (2007). Wolves in Russia: Anxiety throughout the ages, pp.222. ISBN 1550593323.

- ↑ Striped Hyaena Hyaena (Hyaena) hyaena (Linnaeus, 1758). IUCN Species Survival Commission Hyaenidae Specialist Group. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ↑ Dental Encyclopedia. 1800dentist.com. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ Li T-C, Chijiwa K, Sera N, Ishibashi T, Etoh Y, Shinohara Y, et al. (2005). Hepatitis E Virus Transmission from Wild Boar Meat. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet].

- ↑ Celtic Encyclopaedia

- ↑ les-ardennes.net

Seward, Liz, "Pig DNA reveals farming history", BBC News, 4 September 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-18.</ref>

([2]

| |||||||||||||||||

Template:Heraldic creatures

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ M.J. Goulding B.Sc. M.Sc.; G. Smith B.Sc. Ph.D. (March 1998). Current Status and Potential Impact of Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) in the English Countryside: A Risk Assessment. Report to Conservation Management Division C, MAFF.. UK Government, Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=9823&lvl=3&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock Joe Bischoff, Mikhail Domrachev, Scott Federhen, Carol Hotton, Detlef Leipe, Vladimir Soussov, Richard Sternberg, Sean Turner. Taxonomy Browser: Sus Scrofa]. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Retrieved 2007-06-21.