Difference between revisions of "Behavior" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

Humans operate as [[consumer]]s that obtain and use goods. All production is ultimately designed for [[Consumption (economics)|consumption]], and consumers adapt their behavior based on the availability of production. [[Mass consumption]] began during the Industrial Revolution, caused by the development of new technologies that allowed for increased production.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=de Vries |first=Jan |title=The Industrious Revolution: Consumer Behavior and the Household Economy, 1650 to the Present |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2008 |isbn=9780511409936 |pages=4–7}}</ref> Many factors affect a consumer's decision to purchase goods through trade. They may consider the nature of the product, its associated cost, the convenience of purchase, and the nature of [[advertising]] around the product. Cultural factors may influence this decision, as different cultures value different things, and [[subculture]]s within these cultures may have distinct priorities as buyers. [[Social class]], including wealth, education, and occupation may affect one's purchasing behavior. A consumer's interpersonal relationships and [[reference group]]s may also influence purchasing behavior.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Gajjar |first=Nilesh B. |date=2013 |title=Factors Affecting Consumer Behavior |journal=International Journal of Research in Health Science |volume=1 |issue=2 |pages=10–15 |issn=2320-771X}}</ref> | Humans operate as [[consumer]]s that obtain and use goods. All production is ultimately designed for [[Consumption (economics)|consumption]], and consumers adapt their behavior based on the availability of production. [[Mass consumption]] began during the Industrial Revolution, caused by the development of new technologies that allowed for increased production.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=de Vries |first=Jan |title=The Industrious Revolution: Consumer Behavior and the Household Economy, 1650 to the Present |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2008 |isbn=9780511409936 |pages=4–7}}</ref> Many factors affect a consumer's decision to purchase goods through trade. They may consider the nature of the product, its associated cost, the convenience of purchase, and the nature of [[advertising]] around the product. Cultural factors may influence this decision, as different cultures value different things, and [[subculture]]s within these cultures may have distinct priorities as buyers. [[Social class]], including wealth, education, and occupation may affect one's purchasing behavior. A consumer's interpersonal relationships and [[reference group]]s may also influence purchasing behavior.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Gajjar |first=Nilesh B. |date=2013 |title=Factors Affecting Consumer Behavior |journal=International Journal of Research in Health Science |volume=1 |issue=2 |pages=10–15 |issn=2320-771X}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Consumer behavior]] involves the processes consumers go through, and reactions they have towards products or services.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Regents of the University of California|periodical=|publisher=|url=https://csiss.org/|format=|access-date=|last=|date=|year=|language=|pages=|quote=}}</ref> It has to do with consumption, and the processes consumers go through around purchasing and consuming goods and services.<ref name="Szwacka">{{Cite journal|last=Szwacka-Mokrzycka|first=Joanna|date=2015|title=Trends in Consumer Behavior Changes. Overview of Concepts|url=http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?sid=83b2b7c5-d287-4702-8baf-b8b9d6665410%40sessionmgr4004&vid=0&hid=4112&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl&preview=false#AN=112782281&db=bth|journal=Acta Scientiarum Polonorum. Oeconomia|access-date=2016-03-30}}{{Dead link|date=September 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> Consumers recognise needs or wants, and go through a process to satisfy these needs. Consumer behavior is the process they go through as customers, which includes types of products purchased, amount spent, frequency of purchases and what influences them to make the purchase decision or not. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Circumstances that influence consumer behavior are varied, with contributions from both internal and external factors.<ref name="Szwacka"/> Internal factors include attitudes, needs, motives, preferences and perceptual processes, whilst external factors include marketing activities, social and economic factors, and cultural aspects.<ref name="Szwacka"/> Doctor Lars Perner of the University of Southern California claims that there are also physical factors that influence consumer behavior, for example if a consumer is hungry, then this physical feeling of hunger will influence them so that they go and purchase a sandwich to satisfy the hunger.<ref name="Perner">{{Cite web|url=http://www.consumerpsychologist.com/intro_Consumer_Behavior.html|title=Consumer Behaviour|last=Perner|first=Lars|date=2008|website=Consumer Psychologist|access-date=2016-03-30}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | There is a model described by Lars Perner which illustrates the decision-making process with regards to consumer behavior. It begins with recognition of a problem, the consumer recognises a need or want which has not been satisfied. This leads the consumer to search for information, if it is a low involvement product then the search will be internal, identifying alternatives purely from memory. If the product is high involvement then the search be more thorough, such as reading reviews or reports or asking friends. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The consumer will then evaluate his or her alternatives, comparing price, quality, doing trade-offs between products and narrowing down the choice by eliminating the less appealing products until there is one left. After this has been identified, the consumer will purchase the product. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally the consumer will evaluate the purchase decision, and the purchased product, bringing in factors such as value for money, quality of goods and purchase experience.<ref name="Perner"/> However, this logical process does not always happen this way, people are emotional and irrational creatures. People make decisions with emotion and then justify it with logic according to Robert Caladini Ph.D. Psychology.{{citation needed|date=May 2022}} | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Revision as of 16:53, 11 March 2023

Behavior (American English) or behaviour (British English) is the range of actions and mannerisms made by individuals, organisms, systems or artificial entities in some environment. These systems can include other systems or organisms as well as the inanimate physical environment. It is the computed response of the system or organism to various stimuli or inputs, whether internal or external, conscious or subconscious, overt or covert, and voluntary or involuntary.[1]

The main focus of this article is on human behavior.

Models

Biology

Although disagreement exists as to how to precisely define behavior in a biological context, one common interpretation based on a meta-analysis of scientific literature states that "behavior is the internally coordinated responses (actions or inactions) of whole living organisms (individuals or groups) to internal and/or external stimuli".[2]

A broader definition of behavior, applicable to plants and other organisms, is similar to the concept of phenotypic plasticity. It describes behavior as a response to an event or environment change during the course of the lifetime of an individual, differing from other physiological or biochemical changes that occur more rapidly, and excluding changes that are result of development (ontogeny).[3][4]

Behaviors can be either innate or learned from the environment.

Behavior can be regarded as any action of an organism that changes its relationship to its environment. Behavior provides outputs from the organism to the environment.[5]

The endocrine system and the nervous system likely influence human behavior. Complexity in the behavior of an organism may be correlated to the complexity of its nervous system. Generally, organisms with more complex nervous systems have a greater capacity to learn new responses and thus adjust their behavior.[6]

Animals

Ethology is the scientific and objective study of animal behavior, usually with a focus on behavior under natural conditions, and viewing behavior as an evolutionarily adaptive trait.[7] behaviorism is a term that also describes the scientific and objective study of animal behavior, usually referring to measured responses to stimuli or trained behavioral responses in a laboratory context, without a particular emphasis on evolutionary adaptivity.[8]

Humans

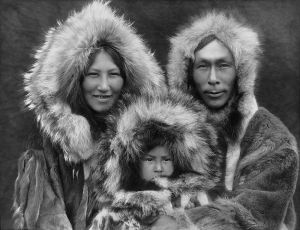

Like all living things, humans live in ecosystems and interact with other organisms. Human behavior is affected by the environment in which a human lives, and environments are affected by human habitation. Humans have also developed man-made ecosystems such as urban areas and agricultural land. Geography and landscape ecology determine how humans are distributed within an ecosystem, both naturally and through planned urban morphology.[9]

Humans exercise control over the animals that live within their environment. Domesticated animals are trained and cared for by humans. Humans can develop social and emotional bonds with animals in their care. Pets are kept for companionship within human homes, including dogs and cats that have been bred for domestication over many centuries. Livestock animals, such as cattle, sheep, goats, and poultry, are kept on agricultural land to produce animal products. Domesticated animals are also kept in laboratories for animal testing. Non-domesticated animals are sometimes kept in nature reserves and zoos for tourism and conservation.[10]

Human behavior

Human behavior is the potential and expressed capacity (mentally, physically, and socially) of human individuals or groups to respond to internal and external stimuli throughout their life.[11][12] Behavior is driven by genetic and environmental factors that affect an individual. Behavior is also driven, in part, by thoughts and feelings, which provide insight into individual psyche, revealing such things as attitudes and values. Human behavior is shaped by psychological traits, as personality types vary from person to person, producing different actions and behavior.

Social behavior accounts for actions directed at others. It is concerned with the considerable influence of social interaction and culture, as well as ethics, interpersonal relationships, politics, and conflict. Some behaviors are common while others are unusual. The acceptability of behavior depends upon social norms and is regulated by various means of social control. Social norms also condition behavior, whereby humans are pressured into following certain rules and displaying certain behaviors that are deemed acceptable or unacceptable depending on the given society or culture.

Cognitive behavior accounts for actions of obtaining and using knowledge. It is concerned with how information is learned and passed on, as well as creative application of knowledge and personal beliefs such as religion. Physiological behavior accounts for actions to maintain the body. It is concerned with basic bodily functions as well as measures taken to maintain health. Economic behavior accounts for actions regarding the development, organization, and use of materials as well as other forms of work. Ecological behavior accounts for actions involving the ecosystem. It is concerned with how humans interact with other organisms and how the environment shapes human behavior.

Human behavior is studied by the social sciences, which include psychology, sociology, ethology, and their various branches and schools of thought. The study of human behavior includes how the human mind evolved and how the nervous system controls behavior. The nature versus nurture debate considers how behavior is affected by genetic and environmental factors. Philosophy of mind considers aspects such as free will, the mind–body problem, and malleability of human behavior. The study of human behavior sometimes receives public attention due to its intersection with cultural issues, including crime, sexuality, and social inequality.[13]

Twin studies are a common method by which human behavior is studied. Twins with identical genomes can be compared to isolate genetic and environmental factors in behavior. Lifestyle, susceptibility to disease, and unhealthy behaviors have been identified to have both genetic and environmental indicators through twin studies.[14]

Factors

Human behavior is influenced by biological and cultural elements. The structure and agency debate considers whether human behavior is predominantly led by individual human impulses or by external structural forces.[15] Behavioral genetics considers how human behavior is affected by inherited traits. Though genes do not guarantee certain behaviors, certain traits can be inherited that make individuals more likely to engage in certain behaviors or express certain personalities.[16] An individual's environment can also affect behavior, often in conjunction with genetic factors. An individual's personality and attitudes affect how behaviors are expressed, formed in conjunction by genetic and environmental factors.[17]

Age

- For more details on this topic, see Aging.

While specific traits of one's personality, temperament, and genetics may be more consistent, other behaviors change as one moves between life stages—i.e., from birth through adolescence, adulthood, and, for example, parenthood and retirement.[11]

Infants are limited in their ability to interpret their surroundings shortly after birth. Object permanence and understanding of motion typically develop within the first six months of an infant's life, though the specific cognitive processes are not understood.[18] The ability to mentally categorize different concepts and objects that they perceive also develops within the first year.[19] Infants are quickly able to discern their body from their surroundings and often take interest in their own limbs or actions they cause by two months of age.[20] Infants practice imitation of other individuals to engage socially and learn new behaviors. In young infants, this involves imitating facial expressions, and imitation of tool use takes place within the first year.[21] Communication develops over the first year, and infants begin using gestures to communicate intention around nine to ten months of age. Verbal communication develops more gradually, taking form during the second year of age.[22]

Children develop fine motor skills shortly after infancy, in the range of three to six years of age, allowing them to engage in behaviors using the hands and eye–hand coordination and perform basic activities of self sufficiency.[23] Children begin expressing more complex emotions in the three to six year old range, including humor, empathy, and altruism, as well engaging in creativity and inquiry.[24] Aggressive behaviors also become varied at this age as children engage in increased physical aggression before learning to favor diplomacy over aggression.[25] Children at this age can express themselves using language with basic grammar.[26] As children grow older, they develop emotional intelligence.[27] Young children engage in basic social behaviors with peers, typically forming friendships centered on play with individuals of the same age and gender.[28] Behaviors of young children are centered around play, which allows them to practice physical, cognitive, and social behaviors.[29] Basic self-concept first develops as children grow, particularly centered around traits such as gender and ethnicity,[30] and behavior is heavily affected by peers for the first time.[31]

Adolescents undergo changes in behavior caused by puberty and the associated changes in hormone production. Production of testosterone increases sensation seeking and sensitivity to rewards in adolescents as well as aggression and risk-taking in adolescent boys. Production of estradiol causes similar risk-taking behavior among adolescent girls. The new hormones cause changes in emotional processing that allow for close friendships, stronger motivations and intentions, and adolescent sexuality.[32] Adolescents undergo social changes on a large scale, developing a full self-concept and making autonomous decisions independently of adults. They typically become more aware of social norms and social cues than children, causing an increase in self-consciousness and adolescent egocentrism that guides behavior in social settings throughout adolescence.[33]

Disability

Physical disabilities can prevent individuals from engaging in typical human behavior or necessitate alternative behaviors. Accommodations and accessibility are often made available for individuals with physical disabilities in developed nations, including health care, assistive technology, and vocational services.[34] Severe disabilities are associated with increased leisure time but also with a lower satisfaction in the quality of leisure time. Productivity and health both commonly undergo long term decline following the onset of a severe disability.[35] Mental disabilities are those that directly affect cognitive and social behavior. Common mental disorders include mood disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and substance dependence.[36]

Social behavior

- For more details on this topic, see Sociology.

Human social behavior is the behavior that considers other humans, including communication and cooperation. It is highly complex and structured, based on advanced theory of mind that allows humans to attribute thoughts and actions to one another. Through social behavior, humans have developed society and culture distinct from other animals.[37] Human social behavior is governed by a combination of biological factors that affect all humans and cultural factors that change depending on upbringing and societal norms.[38] Human communication is based heavily on language, typically through speech or writing. Nonverbal communication and paralanguage can modify the meaning of communications by demonstrating ideas and intent through physical and vocal behaviors.[39]

Social norms

Human behavior in a society is governed by social norms. Social norms are unwritten expectations that members of society have for one another. These norms are ingrained in the particular culture that they emerge from, and humans often follow them unconsciously or without deliberation. These norms affect every aspect of life in human society, including decorum, social responsibility, property rights, contractual agreement, morality, justice, and meaning. Many norms facilitate coordination between members of society and prove mutually beneficial, such as norms regarding communication and agreements. Norms are enforced by social pressure, and individuals that violate social norms risk social exclusion.[40]

Systems of ethics are used to guide human behavior to determine what is moral. Humans are distinct from other animals in the use of ethical systems to determine behavior. Ethical behavior is human behavior that takes into consideration how actions will affect others and whether behaviors will be optimal for others. What constitutes ethical behavior is determined by the individual value judgments of the person and the collective social norms regarding right and wrong. Value judgments are intrinsic to people of all cultures, though the specific systems used to evaluate them may vary. These systems may be derived from divine law, natural law, civil authority, reason, or a combination of these and other principles. Altruism is an associated behavior in which humans consider the welfare of others equally or preferentially to their own. While other animals engage in biological altruism, ethical altruism is unique to humans.[41]

Deviance is behavior that violates social norms. As social norms vary between individuals and cultures, the nature and severity of a deviant act is subjective. What is considered deviant by a society may also change over time as new social norms are developed. Deviance is punished by other individuals through social stigma, censure, or violence. Many deviant actions are recognized as crimes and punished through a system of criminal justice. Deviant actions may be punished to prevent harm to others, to maintain a particular worldview and way of life, or to enforce principles of morality and decency. Cultures also attribute positive value to certain physical traits, causing individuals that do not have these traits to be seen as deviant.[42]

Interpersonal relationships

Interpersonal relationships can be evaluated by the specific choices and emotions between two individuals, or they can be evaluated by the broader societal context of how such a relationship is expected to function. Relationships are developed through communication, which creates intimacy, expresses emotions, and develops identity.[39] An individual's interpersonal relationships form a social group in which individuals all communicate and socialize with one another, and these social groups are connected by additional relationships. Human social behavior is affected not only by individual relationships, but also by how behaviors in one relationship may affect others.[43] Individuals that actively seek out social interactions are extraverts, and those that do not are introverts.[44]

Romantic love is a significant interpersonal attraction toward another. Its nature varies by culture, but it is often contingent on gender, occurring in conjunction with sexual attraction and being either heterosexual or homosexual. It takes different forms and is associated with many individual emotions. Many cultures place a higher emphasis on romantic love than other forms of interpersonal attraction. Marriage is a union between two people, though whether it is associated with romantic love is dependent on the culture.[45] Individuals that are closely related by consanguinity form a family. There are many variations on family structures that may include parents and children as well as stepchildren or extended relatives.[46] Family units with children emphasize parenting, in which parents engage in a high level of parental investment to protect and instruct children as they develop over a period of time longer than that of most other mammals.[47]

Politics and conflict

- Further information: Political science

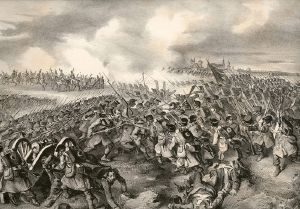

When humans make decisions as a group, they engage in politics. Humans have evolved to engage in behaviors of self-interest, but this also includes behaviors that facilitate cooperation rather than conflict in collective settings. Individuals will often form in-group and out-group perceptions, through which individuals cooperate with the in-group and compete with the out-group. This causes behaviors such as unconsciously conforming, passively obeying authority, taking pleasure in the misfortune of opponents, initiating hostility toward out-group members, artificially creating out-groups when none exist, and punishing those that do not comply with the standards of the in-group. These behaviors lead to the creation of political systems that enforce in-group standards and norms.[48]

When humans oppose one another, it creates conflict. It may occur when the involved parties have a disagreement of opinion, when one party obstructs the goals of another, or when parties experience negative emotions such as anger toward one another. Conflicts purely of disagreement are often resolved through communication or negotiation, but incorporation of emotional or obstructive aspects can escalate conflict. Interpersonal conflict is that between specific individuals or groups of individuals.[49] Social conflict is that between different social groups or demographics. This form of conflict often takes place when groups in society are marginalized, do not have the resources they desire, wish to instigate social change, or wish to resist social change. Significant social conflict can cause civil disorder.[50] International conflict is that between nations or governments. It may be solved through diplomacy or war.

Cognitive behavior

Human cognition is distinct from that of other animals. This is derived from biological traits of human cognition, but also from shared knowledge and development passed down culturally. Humans are able to learn from one another due to advanced theory of mind that allows knowledge to be obtained through education. The use of language allows humans to directly pass knowledge to one another.[51][52] The human brain has neuroplasticity, allowing it to modify its features in response to new experiences. This facilitates learning in humans and leads to behaviors of practice, allowing the development of new skills in individual humans.[52] Behavior carried out over time can be ingrained as a habit, where humans will continue to regularly engage in the behavior without consciously decided to do so.[53]

Humans engage in reason to make inferences with a limited amount of information. Most human reasoning is done automatically without conscious effort on the part of the individual. Reasoning is carried out by making generalizations from past experiences and applying them to new circumstances. Learned knowledge is acquired to make more accurate inferences about the subject. Deductive reasoning infers conclusions that are true based on logical premises, while inductive reasoning infers what conclusions are likely to be true based on context.[54]

Emotion is a cognitive experience innate to humans. Basic emotions such as joy, distress, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust are common to all cultures, though social norms regarding the expression of emotion may vary. Other emotions come from higher cognition, such as love, guilt, shame, embarrassment, pride, envy, and jealousy. These emotions develop over time rather than instantly and are more strongly influenced by cultural factors.[55] Emotions are influenced by sensory information, such as color and music, and moods of happiness and sadness. Humans typically maintain a standard level of happiness or sadness determined by health and social relationships, though positive and negative events have short-term influences on mood. Humans often seek to improve the moods of one another through consolation, entertainment, and venting. Humans can also self-regulate mood through exercise and meditation.[56]

Creativity is the use of previous ideas or resources to produce something original. It allows for innovation, adaptation to change, learning new information, and novel problem solving. Expression of creativity also supports quality of life. Creativity includes personal creativity, in which a person presents new ideas authentically, but it can also be expanded to social creativity, in which a community or society produces and recognizes ideas collectively.[57] Creativity is applied in typical human life to solve problems as they occur. It also leads humans to carry out art and science. Individuals engaging in advanced creative work typically have specialized knowledge in that field, and humans draw on this knowledge to develop novel ideas. In art, creativity is used to develop new artistic works, such as visual art or music. In science, those with knowledge in a particular scientific field can use trial and error to develop theories that more accurately explain phenomena.[58]

Religious behavior is a set of traditions that are followed based on the teachings of a religious belief system. The nature of religious behavior varies depending on the specific religious traditions. Most religious traditions involve variations of telling myths, practicing rituals, making certain things taboo, adopting symbolism, determining morality, experiencing altered states of consciousness, and believing in supernatural beings. Religious behavior is often demanding and has high time, energy, and material costs, and it conflicts with rational choice models of human behavior, though it does provide community-related benefits. Anthropologists offer competing theories as to why humans adopted religious behavior.[59] Religious behavior is heavily influenced by social factors, and group involvement is significant in the development of an individual's religious behavior. Social structures such as religious organizations or family units allow the sharing and coordination of religious behavior. These social connections reinforce the cognitive behaviors associated with religion, encouraging orthodoxy and commitment.[60] According to a Pew Research Center report, 54% of adults around the world state that religion is very important in their lives as of 2018.[61]

Physiological behavior

Humans undergo many behaviors common to animals to support the processes of the human body. Humans eat food to obtain nutrition. These foods may be chosen for their nutritional value, but they may also be eaten for pleasure. Eating often follows a food preparation process to make it more enjoyable.[62] Humans dispose of excess food through waste. Excrement is often treated as taboo, particularly in developed and urban communities where sanitation is more widely available and excrement has no value as fertilizer.[63] Humans also regularly engage in sleep, based on homeostatic and circadian factors. The circadian rhythm causes humans to require sleep at a regular pattern and is typically calibrated to the day-night cycle and sleep-wake habits. Homeostasis is also be maintained, causing longer sleep longer after periods of sleep deprivation. The human sleep cycle takes place over 90 minutes, and it repeats 3-5 times during normal sleep.[64]

There are also unique behaviors that humans undergo to maintain physical health. Humans have developed medicine to prevent and treat illnesses. In industrialized nations, eating habits that favor better nutrition, hygienic behaviors that promote sanitation, medical treatment to eradicate diseases, and the use of birth control significantly improve human health.[65] Humans can also engage in exercise beyond that required for survival to maintain health.[66] Humans engage in hygiene to limit exposure to dirt and pathogens. Some of these behaviors are adaptive while others are learned. Basic behaviors of disgust evolved as an adaptation to prevent contact with sources of pathogens, resulting in a biological aversion to feces, body fluids, rotten food, and animals that are commonly disease vectors. Personal grooming, disposal of human corpses, use of sewerage, and use of cleaning agents are hygienic behaviors common to most human societies.[67]

Humans reproduce sexually, engaging in sexual intercourse for both reproduction and sexual pleasure. Human reproduction is closely associated with human sexuality and an instinctive desire to procreate, though humans are unique in that they intentionally control the number of offspring that they produce.[68] Humans engage in a large variety of reproductive behaviors relative to other animals, with various mating structures that include forms of monogamy, polygyny, and polyandry. How humans engage in mating behavior is heavily influenced by cultural norms and customs.[69] Unlike most mammals, human women ovulate spontaneously rather than seasonally, with a menstrual cycle that typically lasts 25-35 days.[70]

Humans are bipedal and move by walking. Human walking corresponds to the bipedal gait cycle, which involves alternating heel contact and toe off with the ground and slight elevation and rotation of the pelvis. Balance while walking learned during the first 7–9 years of life, and individual humans develop unique gaits while learning to displace weight, adjust center of mass, and correspond neural control with movement.[71] Humans can achieve higher speed by running. The endurance running hypothesis proposes that humans can outpace most other animals over long distances through running, though human running causes a higher rate of energy exertion. The human body self-regulates through perspiration during periods of exertion, allowing humans more endurance than other animals.[72] The human hand is prehensile and capable of grasping objects and applying force with control over the hand's dexterity and grip strength. This allows the use of complex tools by humans.[73]

Economic behavior

Humans engage in predictable behaviors when considering economic decisions, and these behaviors may or may not be rational. Like all animals, humans make basic decisions through cost–benefit analysis and the risk–return spectrum, though humans are able to contemplate these decisions more thoroughly. Human economic decision making is often reference dependent, in which options are weighed in reference to the status quo rather than absolute gains and losses. Humans are also loss averse, fearing loss rather than seeking gain.[74] Advanced economic behavior developed in humans after the Neolithic Revolution and the development of agriculture. These developments led to a sustainable supply of resources that allowed specialization in more complex societies.[75]

Work

The nature of human work is defined by the complexity of society. The simplest societies are tribes that work primarily for sustenance as hunter-gatherers. In this sense, work is not a distinct activity but a constant that makes up all parts of life, as all members of the society must work consistently to stay alive. More advanced societies developed after the Neolithic Revolution, emphasizing work in agricultural and pastoral settings. In these societies, production is increased, ending the need for constant work and allowing some individuals to specialize and work in areas outside of food-production. This also created non-laborious work, as increasing occupational complexity required some individuals to specialize in technical knowledge and administration.[75] Laborious work in these societies has variously been carried out by slaves, serfs, peasants, and guild craftsmen. The nature of work changed significantly during the Industrial Revolution in which the factory system was developed for use by industrializing nations. In addition to further increasing general quality of life, this development changed the dynamic of work. Under the factory system, workers increasingly collaborate with others, employers serve as authority figures during work hours, and forced labor is largely eradicated. Further changes occur in post-industrial societies where technological advance makes industries obsolete, replacing them with mass production and service industries.[76]

Humans approach work differently based on both physical and personal attributes, and some work with more effectiveness and commitment than others. Some find work to contribute to personal fulfillment, while others work only out of necessity.[77] Work can also serve as an identity, with individuals identifying themselves based on their occupation. Work motivation is complex, both contributing to and subtracting from various human needs. The primary motivation for work is for material gain, which takes the form of money in modern societies. It may also serve to create self-esteem and personal worth, provide activity, gain respect, and express creativity.[78] Modern work is typically categorized as laborious or blue-collar work and non-laborious or white-collar work.[79]

Leisure

Leisure is activity or lack of activity that takes place outside of work. It provides relaxation, entertainment, and improved quality of life for individuals. Casual leisure behaviors provide short-term gratification, but they do not provide long-term gratification or personal identity. These include play, relaxation, casual social interaction, volunteering, passive entertainment, active entertainment, and sensory stimulation. Passive entertainment is typically derived from mass media, which may include written works or digital media. Active entertainment involves games in which individuals participate. Sensory stimulation is immediate gratification from behaviors such as eating or sex.[80] Serious leisure behaviors involve non-professional pursuit of arts and sciences, the development of hobbies, or career volunteering in an area of expertise.[81] Leisure can be beneficial for physical and mental health. It may be used to seek temporary relief from psychological stress, to produce positive emotions, or to facilitate social interaction. Leisure can also facilitate health risks and negative emotions caused by boredom, substance abuse, or high-risk behavior.[82]

Consumption

Humans operate as consumers that obtain and use goods. All production is ultimately designed for consumption, and consumers adapt their behavior based on the availability of production. Mass consumption began during the Industrial Revolution, caused by the development of new technologies that allowed for increased production.[15] Many factors affect a consumer's decision to purchase goods through trade. They may consider the nature of the product, its associated cost, the convenience of purchase, and the nature of advertising around the product. Cultural factors may influence this decision, as different cultures value different things, and subcultures within these cultures may have distinct priorities as buyers. Social class, including wealth, education, and occupation may affect one's purchasing behavior. A consumer's interpersonal relationships and reference groups may also influence purchasing behavior.[83]

Consumer behavior involves the processes consumers go through, and reactions they have towards products or services.[84] It has to do with consumption, and the processes consumers go through around purchasing and consuming goods and services.[85] Consumers recognise needs or wants, and go through a process to satisfy these needs. Consumer behavior is the process they go through as customers, which includes types of products purchased, amount spent, frequency of purchases and what influences them to make the purchase decision or not.

Circumstances that influence consumer behavior are varied, with contributions from both internal and external factors.[85] Internal factors include attitudes, needs, motives, preferences and perceptual processes, whilst external factors include marketing activities, social and economic factors, and cultural aspects.[85] Doctor Lars Perner of the University of Southern California claims that there are also physical factors that influence consumer behavior, for example if a consumer is hungry, then this physical feeling of hunger will influence them so that they go and purchase a sandwich to satisfy the hunger.[86]

There is a model described by Lars Perner which illustrates the decision-making process with regards to consumer behavior. It begins with recognition of a problem, the consumer recognises a need or want which has not been satisfied. This leads the consumer to search for information, if it is a low involvement product then the search will be internal, identifying alternatives purely from memory. If the product is high involvement then the search be more thorough, such as reading reviews or reports or asking friends.

The consumer will then evaluate his or her alternatives, comparing price, quality, doing trade-offs between products and narrowing down the choice by eliminating the less appealing products until there is one left. After this has been identified, the consumer will purchase the product.

Finally the consumer will evaluate the purchase decision, and the purchased product, bringing in factors such as value for money, quality of goods and purchase experience.[86] However, this logical process does not always happen this way, people are emotional and irrational creatures. People make decisions with emotion and then justify it with logic according to Robert Caladini Ph.D. Psychology.[citation needed]

Notes

- ↑ Elizabeth A. Minton, Lynn R. Khale (2014). Belief Systems, Religion, and Behavioral Economics. New York: Business Expert Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-60649-704-3.

- ↑ Levitis, Daniel (June 2009). Behavioural biologists do not agree on what constitutes behaviour. Animal Behaviour 78 (1): 103–10.

- ↑ Karban, R. (2008). Plant behaviour and communication. Ecology Letters 11 (7): 727–739, [1] {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}.

- ↑ Karban, R. (2015). Plant Behavior and Communication. In: Plant Sensing and Communication. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 1-8, [2].

- ↑ Dusenbery, David B. (2009). Living at Micro Scale, p. 124. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts Template:ISBN.

- ↑ Gregory, Alan (2015). Book of Alan: A Universal Order. ISBN 978-1-5144-2053-9.

- ↑ Template:Cite dictionary

- ↑ Template:Cite dictionary

Behaviourism. Oxford Dictionaries. - ↑ Steiner, F. (2008). "Human Ecology: Overview", Encyclopedia of Ecology, 1st, Elsevier, 1898–1906. DOI:10.1016/B978-008045405-4.00626-1. ISBN 9780080454054. OCLC 256490644.

- ↑ (2014)Human-animal interactions, relationships and bonds: a review and analysis of the literature. International Journal of Comparative Psychology 27 (1).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kagan, Jerome, Marc H. Bornstein, and Richard M. Lerner. "Human Behaviour {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ↑ Farnsworth, Bryn. 4 July 2019. "Human Behavior: The Complete Pocket Guide {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}." iMotions. Copenhagen. So What Exactly is Behavior? {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}

- ↑ Longino, Helen E. (2013). "Introduction", Studying Human Behavior: How Scientists Investigate Aggression and Sexuality. University of Chicago Press, 1–17. DOI:10.7208/9780226921822. ISBN 9780226921822.

- ↑ (2002)Classical twin studies and beyond. Nature Reviews Genetics 3 (11): 872–882.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 de Vries, Jan (2008). The Industrious Revolution: Consumer Behavior and the Household Economy, 1650 to the Present. Cambridge University Press, 4–7. ISBN 9780511409936.

- ↑ (2008) "Overview", Behavioral Genetics, 5th, Worth Publishers, 1–4. ISBN 9781429205771.

- ↑ (2008) "Genetic and Environmental Influences on Behavior", Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 1st, 58–90. ISBN 9780470007440.

- ↑ Bremner & Wachs 2010, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Bremner & Wachs 2010, pp. 264–265.

- ↑ Bremner & Wachs 2010, pp. 337–340.

- ↑ Bremner & Wachs 2010, pp. 346–347.

- ↑ Bremner & Wachs 2010, pp. 398–399.

- ↑ Woody & Woody 2019, p. 259–260.

- ↑ Woody & Woody 2019, p. 263.

- ↑ Woody & Woody 2019, p. 279.

- ↑ Woody & Woody 2019, p. 268–269.

- ↑ Charlesworth 2019, p. 346.

- ↑ Woody & Woody 2019, p. 281.

- ↑ Woody & Woody 2019, p. 290.

- ↑ Charlesworth 2019, p. 343.

- ↑ Charlesworth 2019, p. 353.

- ↑ (2013) The Teenage Brain: Surging Hormones—Brain-Behavior Interactions During Puberty. Current Directions in Psychological Science 22 (2): 134–139.

- ↑ (2006)Social cognitive development during adolescence. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 1 (3): 165–174.

- ↑ (2005)Disability in Everyday Life. Qualitative Health Research 15 (8): 1037–1054.

- ↑ Powdthavee, Nattavudh (2009-12-01). What happens to people before and after disability? Focusing effects, lead effects, and adaptation in different areas of life. Social Science & Medicine 69 (12): 1834–1844.

- ↑ Krueger, Robert F. (1999-10-01). The Structure of Common Mental Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 56 (10): 921–926.

- ↑ (2006) Roots of Human Sociality. Routledge, 1–3. DOI:10.4324/9781003135517. ISBN 9781003135517.

- ↑ Duck 2007, pp. 1–5.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Duck 2007, pp. 10–14.

- ↑ Young, H. Peyton (2015-08-01). The Evolution of Social Norms. Annual Review of Economics 7 (1): 359–387.

- ↑ Ayala, Francisco J. (2010-05-11). The difference of being human: Morality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (supplement_2): 9015–9022.

- ↑ Goode, Erich (2015). "The Sociology of Deviance: An Introduction", The Handbook of Deviance. Wiley, 3–29. ISBN 9781118701324.

- ↑ Duck 2007, p. 107.

- ↑ Argyle, Michael, and Luo Lu. 1990. "The happiness of extraverts." Personality and Individual Differences 11(10):1011–17. Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1016/0191-8869(90)90128-E .

- ↑ Duck 2007, pp. 56–60.

- ↑ Duck 2007, pp. 121–125.

- ↑ (2001)Evolution of Human Parental Behavior and the Human Family. Parenting 1 (1–2): 5–61.

- ↑ (2004)The Origin of Politics: An Evolutionary Theory of Political Behavior. Perspectives on Politics 2 (4): 707–723.

- ↑ (2004-03-01)Conceptualizing the Construct of Interpersonal Conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management 15 (3): 216–244.

- ↑ Mitchell, Christopher R. (2005). "Conflict, Social Change and Conflict Resolution. An Enquiry.", Berghof Handbook for Conflict Transformation. Berghof Foundation.

- ↑ (2003)What Makes Human Cognition Unique? From Individual to Shared to Collective Intentionality. Mind and Language 18 (2): 121–147.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 (2020)Culture: The Driving Force of Human Cognition. Topics in Cognitive Science 12 (2): 654–672.

- ↑ (2016-01-04)Psychology of Habit. Annual Review of Psychology 67 (1): 289–314.

- ↑ (2019) "Introduction", Human Reasoning: The Psychology of Deduction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317716266.

- ↑ Evans 2003, pp. 1–21.

- ↑ Evans 2003, pp. 47–.

- ↑ Runco, Mark A. (2018). The Nature of Human Creativity. Cambridge University Press, 246–263. DOI:10.1017/9781108185936.018. ISBN 9781108185936.

- ↑ Simon, Herbert A. (2001). Creativity in the Arts and the Sciences. The Kenyon Review 23 (2): 203–220.

- ↑ (2003-11-24)Signaling, solidarity, and the sacred: The evolution of religious behavior. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 12 (6): 264–274.

- ↑ Cornwall, Marie (1989). The Determinants of Religious Behavior: A Theoretical Model and Empirical Test. Social Forces 68 (2): 572–592.

- ↑ 'How religious commitment varies by country among people of all ages. Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life (13 June 2018).

- ↑ (2012) Essentials of Human Nutrition, 4th, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1. ISBN 978-0-19-956634-1.

- ↑ Jewitt, Sarah (2011). Geographies of shit: Spatial and temporal variations in attitudes towards human waste. Progress in Human Geography 35 (5): 608–626.

- ↑ Gillberg, M. (1997). Human sleep/wake regulation. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. Supplementum 110: 8–10.

- ↑ McKeown, Thomas (1980). The Role of Medicine. Princeton University Press, 78. ISBN 9781400854622.

- ↑ (2012) Exercise acts as a drug; the pharmacological benefits of exercise: Exercise acts as a drug. British Journal of Pharmacology 167 (1): 1–12.

- ↑ Curtis, Valerie A. (2007). A Natural History of Hygiene. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology 18 (1): 11–14.

- ↑ Baggott, L. M. (1997-02-20). Human Reproduction (in en). Cambridge University Press, 5. ISBN 978-0-521-46914-2.

- ↑ Newson, Lesley (2013). "Cultural Evolution and Human Reproductive Behavior", Building Babies: Primate Development in Proximate and Ultimate Perspective. New York, NY: Springer, 487. ISBN 978-1-4614-4060-4. OCLC 809201501.

- ↑ (2013-09-28) Human Reproductive Biology (in en). Academic Press, 63. ISBN 978-0-12-382185-0.

- ↑ Inman, Verne T. (1966-05-14). Human Locomotion. Canadian Medical Association Journal 94 (20): 1047–1054.

- ↑ (1984-08-01)The Energetic Paradox of Human Running and Hominid Evolution [and Comments and Reply]. Current Anthropology 25 (4): 483–495.

- ↑ (2001-12-01)Characterizing human hand prehensile strength by force and moment wrench. Ergonomics 44 (15): 1392–1402.

- ↑ (2009-02-01)Economic cognition in humans and animals: the search for core mechanisms. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 19 (1): 63–66.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Neff 1985, pp. 24–33.

- ↑ Neff 1985, pp. 41–46.

- ↑ Neff 1985, p. 2.

- ↑ Neff 1985, pp. 142–153.

- ↑ Neff 1985, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Stebbins, Robert A. (2001-01-01). The costs and benefits of hedonism: some consequences of taking casual leisure seriously. Leisure Studies 20 (4): 305–309.

- ↑ Stebbins, Robert A. (2001). Serious Leisure. Society 38 (4): 53–57.

- ↑ Caldwell, Linda L. (2005-02-01). Leisure and health: why is leisure therapeutic?. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 33 (1): 7–26.

- ↑ Gajjar, Nilesh B. (2013). Factors Affecting Consumer Behavior. International Journal of Research in Health Science 1 (2): 10–15.

- ↑ The Regents of the University of California.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 Szwacka-Mokrzycka, Joanna (2015). Trends in Consumer Behavior Changes. Overview of Concepts. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum. Oeconomia.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Perner, Lars (2008). Consumer Behaviour.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- (2010) The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, 2nd, Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-3273-5.

- Charlesworth, Leanne Wood (2019). "Early Childhood", Dimensions of Human Behavior: The Changing Life Course, 6th, SAGE Publications, 327–395. ISBN 9781544339344.

- Duck, Steve (2007). Human Relationships, 4th, SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781412929998.

- Evans, Dylan (2003). Emotion: A Very Short Introduction, 1st, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192804617.

- Neff, Walter S. (1985). Work and Human Behavior, 3rd, Aldine Publishing Company. ISBN 0202303195.

- (2019) "Early Childhood", Dimensions of Human Behavior: The Changing Life Course, 6th, SAGE Publications, 251–326. ISBN 9781544339344.

- General

- Cao, L. (2014). Behavior Informatics: A New Perspective. IEEE Intelligent Systems (Trends and Controversies), 29(4): 62–80.

- (2008). How Information Changes Consumer Behavior and How Consumer Behavior Determines Corporate Strategy. Journal of Management Information Systems 25 (2): 13–40.

- (2013). Hitting Your Target. Marketing Insights 35 (2): 32–38.

- Perner, L. (2008), Consumer behavior. University of Southern California, Marshall School of Business. Retrieved from http://www.consumerpsychologist.com/intro_Consumer_Behavior.html

- (2015). TRENDS IN CONSUMER behavior CHANGES. OVERVIEW OF CONCEPTS. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum. Oeconomia 14 (3): 149–156.

Further reading

- Bateson, P. (2017) behavior, Development and Evolution. Open Book Publishers, Cambridge. Template:ISBN.

- (24 September 2012) Behavioral Genetics, Shaun Purcell (Appendix: Statistical Methods in Behavioral Genetics), Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-4215-8.

- {{cite book |last1=Flint |first1=Jonathan |last2=Greenspan |first2=Ralph J. |last3=Kendler |first3=Kenneth S. |title=How Genes Influence Behavior |url=https://archive.org/details/howgenesinfl_flin_2010_000_10540804 |url-access=registration |date=28 January 2010 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-955990-9

- Ardrey, Robert. 1970. The Social Contract: A Personal Inquiry into the Evolutionary Sources of Order and Disorder. Atheneum. Template:ISBN.

- Sapolsky, Robert M. (2017). Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1594205071.

External links

- What is behavior? Baby don't ask me, don't ask me, no more at Earthling Nature.

- www.behaviorinformatics.org

- Links to review articles by Eric Turkheimer and co-authors on behavior research

- Links to IJCAI2013 tutorial on behavior informatics and computing

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.