Difference between revisions of "Abortion" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 171: | Line 171: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* Critchlow, Donald T. ''The Politics of Abortion and Birth Control in Historical Perspective'' (1996) | * Critchlow, Donald T. ''The Politics of Abortion and Birth Control in Historical Perspective'' (1996) | ||

| − | * Critchlow, Donald T. ''Intended Consequences: Birth Control, Abortion, and the Federal Government in Modern America'' (2001) | + | * Critchlow, Donald T. ''Intended Consequences: Birth Control, Abortion, and the Federal Government in Modern America'' (2001). ISBN 0195145933 |

| − | * Garrow, David J. ''Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe V. Wade'' (1998) | + | * Garrow, David J. ''Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe V. Wade'' (1998). ISBN 0025427555 |

| − | * Hull, N.E.H. ''Roe V. Wade: The Abortion Rights Controversy in American History'' (2001). Legal history. | + | * Hull, N.E.H. ''Roe V. Wade: The Abortion Rights Controversy in American History'' (2001). Legal history. ISBN 0700611436 |

| − | * Mohr, James C. ''Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy, 1800-1900'' (1979) | + | * Mohr, James C. ''Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy, 1800-1900'' (1979). ISBN 0195026160 |

| − | * Staggenborg. Suzanne. ''The Pro-Choice Movement: Organization and Activism in the Abortion Conflict'' (1994) | + | * Staggenborg. Suzanne. ''The Pro-Choice Movement: Organization and Activism in the Abortion Conflict'' (1994). ISBN 0195089251 |

| − | * Rubin, Eva R. ed. ''The Abortion Controversy: A Documentary History'' (1994) | + | * Rubin, Eva R. ed. ''The Abortion Controversy: A Documentary History'' (1994). ISBN 0313284768 |

| − | * Hull, N.E.H. ''The Abortion Rights Controversy in America: A Legal Reader'' (2004) | + | * Hull, N.E.H. ''The Abortion Rights Controversy in America: A Legal Reader'' (2004). ISBN 0807855359 |

| − | * Reagan, Leslie J. ''When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United State, 1867-1973'' (1997) | + | * Reagan, Leslie J. ''When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United State, 1867-1973'' (1997). ISBN 0520216571 |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 20:10, 4 August 2007

An abortion is the removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus from the uterus, resulting in or caused by its death. This can occur spontaneously as a miscarriage, or be artificially induced by chemical, surgical or other means. Commonly, "abortion" refers to an induced procedure at any point during human pregnancy; medically, it is defined as miscarriage or induced termination before twenty weeks' gestation, which is considered nonviable.

Throughout history, abortion has been induced by various methods. The moral and legal aspects of abortion are subject to intense debate in many parts of the world.

Definitions

The following medical terms are used to categorize abortion:

- Spontaneous abortion (miscarriage): An abortion due to accidental trauma or natural causes. Most miscarriages are due to incorrect replication of chromosomes; they can also be caused by environmental factors.

- Induced abortion: Abortion that has been caused by deliberate human action. Induced abortions are further sub-categorized into therapeutic and elective:

- Therapeutic abortion:

- To save the life of the pregnant woman.[1]

- To preserve the woman's physical or mental health.[1]

- To terminate pregnancy that would result in a child born with a congenital disorder that would be fatal or associated with significant morbidity.[1]

- To selectively reduce the number of fetuses to lessen health risks associated with multiple pregnancy.[1]

- Elective abortion: Abortion performed for any other reason.

- Therapeutic abortion:

During the 1950s in the United States, guidelines were set that allowed therapeutic abortion if

- pregnancy would "gravely impair the physical and mental health of the mother,"

- the child born was likely to have "grave physical and mental defects," or

- the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest[2]

The United States Supreme Court 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade upheld the fundamental right of a woman to determine whether to continue her pregnancy, deeming legislation that overly restricted abortion as unconstitutional.

In common parlance, the term "abortion" is synonymous with induced abortion. However, in medical texts, the word 'abortion' might exclusively refer to, or may also refer to, spontaneous abortion (miscarriage).

Spontaneous abortion

Spontaneous abortions, generally referred to as miscarriages, occur when an embryo or fetus is lost due to natural causes before the 20th week of gestation. A pregnancy that ends earlier than 37 weeks of gestation, if it results in a live-born infant, is known as a "premature birth." When a fetus dies in the uterus at some point late in gestation, beginning at about 20 weeks, or during delivery, it is termed a "stillbirth." Premature births and stillbirths are generally not considered to be miscarriages although usage of these terms can sometimes overlap.

Most miscarriages occur very early in pregnancy. Between 10% and 50% of pregnancies end in miscarriage, depending upon the age and health of the pregnant woman.[3] In most cases, they occur so early in the pregnancy that the woman is not even aware that she was pregnant.

The risk of spontaneous abortion decreases sharply after the 8th week.[4] This risk is greater in those with a known history of several spontaneous abortions or an induced abortion, those with systemic diseases, and those over age 35. Other causes can be infection (of either the woman or fetus), immune response, or serious systemic disease. A spontaneous abortion can also be caused by accidental trauma; intentional trauma to cause miscarriage is considered induced abortion or feticide.

Induced abortion

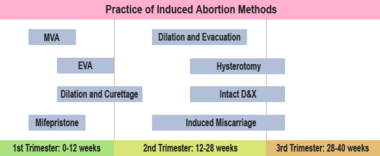

A pregnancy can be intentionally aborted in many ways. The manner selected depends chiefly upon the gestational age of the fetus, in addition to the legality, regional availability, and doctor-patient preference for specific procedures.

Surgical abortion

In the first twelve weeks, suction-aspiration or vacuum abortion is the most common method.[5] Manual vacuum aspiration, or MVA abortion, consists of removing the fetus or embryo by suction using a manual syringe, while the Electric vacuum aspiration or EVA abortion method uses an electric pump. These techniques are comparable, differing in the mechanism used to apply suction, how early in pregnancy they can be used, and whether cervical dilation is necessary. MVA, also known as "mini-suction" and menstrual extraction, can be used in very early pregnancy, and does not require cervical dilation. Surgical techniques are sometimes referred to as STOP: 'Suction (or surgical) Termination Of Pregnancy'. From the fifteenth week until approximately the twenty-sixth week, a dilation and evacuation (D & E) is used. D & E consists of opening the cervix of the uterus and emptying it using surgical instruments and suction.

Dilation and curettage (D & C) is a standard gynecological procedure performed for a variety of reasons, including examination of the uterine lining for possible malignancy, investigation of abnormal bleeding, and abortion. Curettage refers to cleaning the walls of the uterus with a curette. The World Health Organization recommends this procedure, also called Sharp Curettage, only when MVA is unavailable.[6] The term "D and C," or sometimes suction curette, is used as a euphemism for the first trimester abortion procedure, whichever the method used.

Other techniques must be used to induce abortion in the third trimester. Premature delivery can be induced with prostaglandin; this can be coupled with injecting the amniotic fluid with caustic solutions containing saline or urea. Very late abortions can be induced by intact dilation and extraction (IDX) (also called intrauterine cranial decompression), which requires surgical decompression of the fetus's head before evacuation. IDX is sometimes termed as "partial-birth abortion." A hysterotomy abortion, similar to a caesarian section but resulting in a terminated fetus, can also be used at late stages of pregnancy. It can be performed vaginally, with an incision just above the cervix, in the late mid-trimester.

From the 20th to 23rd week of gestation, an injection to stop the fetal heart can be used as the first phase of the surgical abortion procedure.[7]

Medical abortion

Effective in the first trimester of pregnancy, medical (sometimes called chemical abortion), or non-surgical abortions comprise 10% of all abortions in the United States and Europe. Combined regimens include methotrexate or mifepristone (also known as RU-486), followed by a prostaglandin (either misoprostol or gemeprost: misoprostol is used in the U.S.; gemeprost is used in the UK and Sweden.) When used within 49 days gestation, approximately 92% of women undergoing medical abortion with a combined regimen completed it without surgical intervention.[8] Misoprostol can be used alone, but has a lower efficacy rate than combined regimens. In cases of failure of medical abortion, vacuum or manual aspiration is used to complete the abortion surgically.

Other means of abortion

Historically, a number of herbs reputed to possess abortifacient properties have been used in folk medicine: tansy, pennyroyal, black cohosh, and the now-extinct silphium (see history of abortion).[9] The use of herbs in such a manner can cause serious — even lethal — side effects, such as multiple organ failure, and is not recommended by physicians.[10]

Abortion is sometimes attempted by causing trauma to the abdomen. The degree of force, if severe, can cause serious internal injuries without necessarily succeeding in inducing miscarriage.[11] Both accidental and deliberate abortions of this kind can be subject to criminal liability in many countries. In Burma, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, there is an ancient tradition of attempting abortion through forceful abdominal massage.[12]

Reported methods of unsafe, self-induced abortion include misuse of misoprostol, and insertion of non-surgical implements such as knitting needles and clothes hangers into the uterus.

History

Induced abortion, according to some anthropologists, can be traced to ancient times.[13] There is evidence to suggest that, historically, pregnancies were terminated through a number of methods, including the administration of abortifacient herbs, the use of sharpened implements, the application of abdominal pressure, and other techniques.

The Hippocratic Oath, the chief statement of medical ethics in Ancient Greece, forbade all doctors from helping to procure an abortion by pessary. Nonetheless, Soranus, a second-century Greek physician, suggested in his work Gynaecology that women wishing to abort their pregnancies should engage in violent exercise, energetic jumping, carrying heavy objects, and riding animals. He also prescribed a number of recipes for herbal baths, pessaries, and bloodletting, but advised against the use of sharp instruments to induce miscarriage due to the risk of organ perforation.[14] It is also believed that, in addition to using it as a contraceptive, the ancient Greeks relied upon silphium as an abortifacient. Such folk remedies, however, varied in effectiveness and were not without risk. Tansy and pennyroyal, for example, are two poisonous herbs with serious side effects that have at times been used to terminate pregnancy.

Abortion laws and their enforcement have fluctuated through various eras. Many early laws and church doctrine focused on "quickening," when a fetus began to move on its own, as a way to differentiate when an abortion became impermissible. In the 18th–19th centuries various doctors, clerics, and social reformers successfully pushed for an all-out ban on abortion. During the 20th century abortion has become legal in many Western countries, but it is regularly subjected to legal challenges and restrictions by pro-life groups.[15]

Prehistory to 5th century

The first recorded evidence of induced abortion is from a Chinese document which records abortions performed upon royal concubines in China between the years 500 and 515 B.C.E.[16] According to Chinese folklore, the legendary Emperor Shennong prescribed the use of mercury to induce abortions nearly 5000 years ago.[17]

Abortion, along with infanticide, was well known in the ancient Greco-Roman world. Numerous methods of abortion were used, "the more effective of which were exceedingly dangerous." Several common methods involved either dosing the pregnant woman with a near-fatal amount of poison, in order to induce a miscarriage, introducing poison directly into the uterus, or prodding the uterus with one of a variety of "long needles, hooks, and knives".[18] Unsurprisingly, these methods often led to the death of the woman, as well as the fetus.

There have been archaeological discoveries which would seem to indicate early surgical attempts at the extraction of a fetus; however, such methods are not believed to have been common, given the infrequency with which they are mentioned in ancient medical texts.[19] Many of the methods employed in early and primitive cultures were non-surgical. Physical activities like strenuous labour, climbing, paddling, weightlifting, or diving were a common technique. Others included the use of irritant leaves, fasting, bloodletting, pouring hot water onto the abdomen, and lying on a heated coconut shell.[13] In primitive cultures, techniques developed through observation, adaptation of obstetrical methods, and transculturation.[20]

5th century to 16th century

An 8th century Sanskrit text instructs women wishing to induce an abortion to sit over a pot of steam or stewed onions.[21]

The technique of massage abortion, involving the application of pressure to the pregnant abdomen, has been practiced in Southeast Asia for centuries. One of the bas reliefs decorating the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, dated circa 1150, depicts a demon performing such an abortion upon a woman who has been sent to the underworld. This is believed to be the oldest known visual representation of abortion.[12]

Japanese documents show records of induced abortion from as early as the 12th century. It became much more prevalent during the Edo period, especially among the peasant class, who were hit hardest by the recurrent famines and high taxation of the age.[22] Statues of the Boddhisattva Jizo, erected in memory of an abortion, miscarriage, stillbirth, or young childhood death, began appearing at least as early as 1710 at a temple in Yokohama (see religion and abortion).[23]

Physical means of inducing abortion, such as battery, exercise, and tightening the girdle — special bands were sometimes worn in pregnancy to support the belly — were reported among English women during the early modern period.[24]

17th-19th centuries

Nineteenth century medicine saw advances in the fields of surgery, anaesthesia, and sanitation, in the same era that doctors with the American Medical Association lobbied for bans on abortion in the United States [25] and the British Parliament passed the Offences Against the Person Act.

Various methods of abortion were documented regionally in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. After a rash of unexplained miscarriages in Sheffield, England, were attributed to lead poisoning caused by the metal pipes which fed the city's water supply, a woman confessed to having used diachylon — a lead-containing plaster — as an abortifacient in 1898.[12] Criminal investigation of an abortionist in Calgary, Alberta in 1894 revealed through chemical analysis that the concotion he had supplied to a man seeking an abortifacient contained Spanish fly.[26]

A well-known example of a Victorian-era abortionist was Madame Restell, or Ann Lohman, who over a forty year period illicitly provided both surgical abortion and abortifacient pills in the northern United States. She began her business in New York during the 1830s, and, by the 1840s, had expanded to include franchises in Boston and Philadelphia.

Women of Jewish descent in Lower East Side, Manhattan are said to have carried the ancient Indian practice of sitting over a pot of steam into the early 20th century. [21] Dr. Evelyn Fisher wrote of how women living in a mining town in Wales during the 1920s used candles intended for Roman Catholic ceremonies to dilate the cervix in an effort to self-induce abortion.[12] Similarly, the use of candles and other objects, such as glass rods, penholders, curling irons, spoons, sticks, knives, and catheters was reported during the 19th-century in the United States.[27]

A paper published in 1870 on the abortion services to be found in Syracuse, New York, concluded that the method most often practiced there during this time was to flush inside of the uterus with injected water. The article's author, Ely Van de Warkle, claimed this procedure was affordable even to a maid, as a man in town offered it for $10 on an installment plan.[28] Other prices which 19th-century abortionists are reported to have charged were much more steep. In Great Britain, it could cost from 10 to 50 guineas, or 5% of the yearly income of a lower middle class household.[12]

Māori who lived in New Zealand before or at the time of colonisation terminated pregnancies via miscarriage-inducing drugs, ceremonial methods, and girding of the abdomen with a restrictive belt.[29] Another source claims that the Māori people did not practice abortion, for fear of Makutu, but did attempt feticide through the artificial induction of premature labor.[30]

20th Century

Although prototypes of the modern curette are referred to in ancient texts, the instrument which is used today was initially designed in France in 1723, but was not applied specifically to a gynecological purpose until 1842.[31] Dilation and curettage has been practiced since the late 19th century.[31]

The 20th century saw improvements in abortion technology, increasing its safety, and reducing its side-effects. Vacuum devices, first described in medical literature in the 1800s, allowed for the development of suction-aspiration abortion.[31] This method was practiced in the Soviet Union, Japan, and China, before being introduced to Britain and the United States in the 1960s.[31] The invention of the Karman cannula, a flexible plastic cannula which replaced earlier metal models in the 1970s, reduced the occurrence of perforation and made suction-aspiration methods possible under local anesthesia.[31] In 1971, Lorraine Rothman and Carol Downer, founding members of the feminist self-help movement, invented the Del-Em, a safe, cheap suction device that made it possible for people with minimal training to perform early abortions called menstrual extraction.[31]

Intact dilation and extraction was developed by Dr. James McMahon in 1983. It resembles a procedure used in the 19th century to save a woman's life in cases of obstructed labor, in which the fetal skull was first punctured with a perforator, then crushed and extracted with a forceps-like instrument, known as a cranioclast.[32][33] In 1980, researchers at Roussel Uclaf in France developed mifepristone, a chemical compound which works as an abortifacient by blocking hormone action. It was first marketed in France under the trade name Mifegyne in 1988.

Debate

Over the course of the history of abortion, induced abortion has been the source of considerable debate, controversy, and activism. An individual's position on the complex ethical, moral, philosophical, biological, and legal issues is often related to his or her value system. Opinions of abortion may be best described as being a combination of beliefs on its morality, and beliefs on the responsibility, ethical scope, and proper extent of governmental authorities in public policy. Religious ethics also has an influence upon both personal opinion and the greater debate over abortion (see religion and abortion).

Abortion debates, especially pertaining to abortion laws, are often spearheaded by advocacy groups belonging to one of two camps. In the United States, most often those in favor of legal prohibition of abortion describe themselves as pro-life while those against legal restrictions on abortion describe themselves as pro-choice. Both are used to indicate the central principles in arguments for and against abortion: "Is the fetus a human being with a fundamental right to life?" for pro-life advocates, and, for those who are pro-choice, "Does a woman have the right to choose whether or not to continue a pregnancy?"

In both public and private debate, arguments presented in favor of or against abortion focus on either the moral permissibility of an induced abortion, or justification of laws permitting or restricting abortion. Arguments on morality and legality tend to collide and combine, complicating the issue at hand.

Debate also focuses on whether the pregnant woman should have to notify and/or have the consent of others in distinct cases: a minor, her parents; a legally-married or common-law wife, her husband; or a pregnant woman, the biological father. In a 2003 Gallup poll in the United States, 72% of respondents were in favor of spousal notification, with 26% opposed; of those polled, 79% of males and 67% of females responded in favor.[34]

Social Issues

A number of complex issues exist in the debate over abortion. These, like the suggested effects upon health listed above, are a focus of research and a fixture of discussion among members on all sides of the controversy.

Effect upon crime rate

A controversial theory attempts to draw a correlation between the United States' unprecedented nationwide decline of the overall crime rate during the 1990s and the decriminalization of abortion 20 years prior.

The suggestion was brought to widespread attention by a 1999 academic paper, The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime, authored by the economists Steven D. Levitt and John Donohue. They attributed the drop in crime to a reduction in individuals said to have a higher statistical probability of committing crimes: unwanted children, especially those born to mothers who are African-American, impoverished, adolescent, uneducated, and single. The change coincided with what would have been the adolescence, or peak years of potential criminality, of those who had not been born as a result of Roe v. Wade and similar cases. Donohue and Levitt's study also noted that states which legalized abortion before the rest of the nation experienced the lowering crime rate pattern earlier, and those with higher abortion rates had more pronounced reductions.[35]

Fellow economists Christopher Foote and Christopher Goetz criticized the methodology in the Donohue-Levitt study, noting a lack of accommodation for statewide yearly variations such as cocaine use, and recalculating based on incidence of crime per capita; they found no statistically significant results.[36] Levitt and Donohue responded to this by presenting an adjusted data set which took into account these concerns and reported that the data maintained the statistical significance of their initial paper.[37]

Such research has been criticized by some as being utilitarian, discriminatory as to race and socioeconomic class, and as promoting eugenics as a solution to crime.[38][39] Levitt states in his book, Freakonomics, that they are neither promoting nor negating any course of action — merely reporting data as economists.

Sex-selective abortion

The advent of both sonography and amniocentesis has allowed parents to determine sex before birth. This has led to the occurrence of sex-selective abortion or the targeted termination of a fetus based upon its sex.

It is suggested that sex-selective abortion might be partially responsible for the noticeable disparities between the birth rates of male and female children in some places. The preference for male children is reported in many areas of Asia, and abortion used to limit female births has been reported in Mainland China, Taiwan, South Korea, and India.[40]

In India, the economic role of men, the costs associated with dowries, and a Hindu tradition which dictates that funeral rites must be performed by a male relative have led to a cultural preference for sons.[41] The widespread availability of diagnostic testing, during the 1970s and '80s, led to advertisements for services which read, "Invest 500 rupees [for a sex test] now, save 50,000 rupees [for a dowry] later."[42] In 1991, the male-to-female sex ratio in India was skewed from its biological norm of 105 to 100, to an average of 108 to 100.[43] Researchers have asserted that between 1985 and 2005 as many as 10 million female fetuses may have been selectively aborted.[44] The Indian government passed an official ban of pre-natal sex screening in 1994 and moved to pass a complete ban of sex-selective abortion in 2002.[45]

In the People's Republic of China, there is also a historic son preference. The implementation of the one-child policy in 1979, in response to population concerns, led to an increased disparity in the sex ratio as parents attempted to circumvent the law through sex-selective abortion or the abandonment of unwanted daughters.[46] Sex-selective abortion might be an influence on the shift from the baseline male-to-female birth rate to an elevated national rate of 117:100 reported in 2002. The trend was more pronounced in rural regions: as high as 130:100 in Guangdong and 135:100 in Hainan.[47] A ban upon the practice of sex-selective abortion was enacted in 2003.[48]

Unsafe abortion

Where and when access to safe abortion has been barred, due to explicit sanctions or general unavailability, women seeking to terminate their pregnancies have sometimes resorted to unsafe methods.

"Back-alley abortion" is a slang term for any abortion not practiced under generally accepted standards of sanitation and professionalism. The World Health Organization defines an unsafe abortion as being, "a procedure...carried out by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both."[49] This can include a person without medical training, a professional health provider operating in sub-standard conditions, or the woman herself.

Unsafe abortion remains a public health concern today due to the higher incidence and severity of its associated complications, such as incomplete abortion, sepsis, hemorrhage, and damage to internal organs. WHO estimates that 19 million unsafe abortions occur around the world annually and that 68,000 of these result in the woman's death.[49] Complications of unsafe abortion are said to account, globally, for approximately 13% of all maternal mortalities, with regional estimates including 12% in Asia, 25% in Latin America, and 13% in sub-Saharan Africa.[50] Health education, access to family planning, and improvements in health care during and after abortion have been proposed to address this phenomenon.[51]

Religious Views

Many major religions are at least nominally opposed to abortion. The Catholic Church argues that life begins at conception, and therefore intentional abortion is the willful taking of a life. Some Protestant sects such as the Lutherans and Calvinists share the Catholic perspective. There is, however, no direct reference to abortion in the New Testament. The Unification Church believes that while life begins at conception, the soul does not enter the body until the child draws its first breath. Judaism does not explicitly ban abortion, but does mention that if a woman suffers a miscarriage due to a quarrel, the guilty person is required to pay a fine, or if the woman dies, the guilty person must pay with their life (Ex. 21:22-23). Orthodox Judaism does prohibit abortions. The Islamic Koran generally forbids abortion out of respect for God as the cause of life. There are two exceptions to this rule: when the woman's life is in danger and when the pregnancy is the result of rape without marriage. In Hinduism, abortion is not acceptable and is considered to be murder as conception is the moment when a person's spirit is united with their matter (Kaushitake Upanishad 111.1). Buddhism, too, condemns abortion as murder. Buddhism does, however, focus on a person's good intentions, creating leeway for those who pursue abortions in order to spare the unborn child a difficult life due to congenital deformities or other such hardships. Traditional Chinese religions operate under the belief that life begins at birth, which has culminated in a less restrictive view of abortion.

Abortion Law

Before the scientific discovery that human development begins at fertilization, English common law allowed abortions to be performed before "quickening," the earliest perception of fetal movement by a woman during pregnancy, until both pre- and post-quickening abortions were criminalized by Lord Ellenborough's Act in 1803.[52] In 1861, the British Parliament passed the Offences Against the Person Act, which continued to outlaw abortion and served as a model for similar prohibitions in some other nations. [53] The Soviet Union, with legislation in 1920, and Iceland, with legislation in 1935, were two of the first countries to generally allow abortion. The second half of the 20th century saw the liberalization of abortion laws in other countries. The Abortion Act 1967 allowed abortion for limited reasons in the United Kingdom. In the 1973 case, Roe v. Wade, the United States Supreme Court struck down state laws banning abortion, ruling that such laws violated an implied right to privacy in the United States Constitution. The Supreme Court of Canada, similarly, in the case of R. v. Morgentaler, discarded its criminal code regarding abortion in 1988, after ruling that such restrictions violated the security of person guaranteed to women under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Canada later struck down provincial regulations of abortion in the case of R. v. Morgentaler (1993). By contrast, abortion in Ireland was affected by the addition of an amendment to the Irish Constitution in 1983 by popular referendum, recognizing "the right to life of the unborn."

Current laws pertaining to abortion are diverse. Religious, moral, and cultural sensibilities continue to influence abortion laws throughout the world. The right to life, the right to liberty, and the right to security of person are major issues of human rights that are sometimes used as justification for the existence or absence of laws controlling abortion. Many countries in which abortion is legal require that certain criteria be met in order for an abortion to be obtained, often, but not always, using a trimester-based system to regulate the window of legality:

- In the United States, some states impose a 24-hour waiting period before the procedure, prescribe the distribution of information on fetal development, or require that parents be contacted if their minor daughter requests an abortion.

- In the United Kingdom, as in some other countries, two doctors must first certify that an abortion is medically or socially warranted before it can be performed. However, since UK law stipulates that a woman seeking an abortion should never be barred from seeking another doctor's referral, and since some doctors believe that abortion is in all cases medically or socially warranted, in practice women are never fully barred from obtaining an abortion.[54]

Other countries, in which abortion is normally illegal, will allow one to be performed in the case of rape, incest, or danger to the pregnant woman's life or health. A few nations ban abortion entirely: Chile, El Salvador, Malta, and Nicaragua, although in 2006 the Chilean government began the free distribution of emergency contraception.[55][56] In Bangladesh, abortion is illegal, but the government has long supported a network of "menstrual regulation clinics," where menstrual extraction (manual vacuum aspiration) can be performed as menstrual hygiene.[57]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Roche, Natalie E. (2004). Therapeutic Abortion. Retrieved 2006-03-08.

- ↑ D. R. Mcfarlane "Induced Abortion: An Historical Overview" in American Journal of Gynecological Health (1993) May-Jun; 7(3): 77-82)

- ↑ "Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Recurrent Pregnancy Loss (Recurrent Miscarriage)." (n.d.) Retrieved 2006-01-18 from Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology web site.

- ↑ Q&A: Miscarriage. (August 6 , 2002). BBC News. Retrieved January 10, 2007. Lennart Nilsson. (1990) A Child is Born.

- ↑ Healthwise. Manual and vacuum aspiration for abortion. (2004). WebMD. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2003). Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ -Vause S, Sands J, Johnston TA, Russell S, Rimmer S. (2002). PMID 12521492 Could some fetocides be avoided by more prompt referral after diagnosis of fetal abnormality? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 May;22(3):243-5. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

-Dommergues M, Cahen F, Garel M, Mahieu-Caputo D, Dumez Y. (2003). PMID 12576743 Feticide during second- and third-trimester termination of pregnancy: opinions of health care professionals. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2003 Mar-Apr;18(2):91-7. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

-Bhide A, Sairam S, Hollis B, Thilaganathan B. (2002). PMID 12230443 Comparison of feticide carried out by cordocentesis versus cardiac puncture. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Sep;20(3):230-2. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

-Senat MV, Fischer C, Bernard JP, Ville Y. (2003). PMID 12628271 The use of lidocaine for fetocide in late termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 2003 Mar;110(3):296-300. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

- MV, Fischer C, Ville Y. (2002). PMID 12001185 Funipuncture for fetocide in late termination of pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. 2002 May;22(5):354-6. Retrieved 2006-03-17. - ↑ Spitz, I.M. et al (1998). Early pregnancy termination with mifepristone and misoprostol in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 338 (18). PMID 9562577.

- ↑ Riddle, John M. (1997). Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Ciganda, C., & Laborde, A. (2003). Herbal infusions used for induced abortion. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol, 41(3), 235-9. Retrieved 2006-01-25.

- ↑ Education for Choice. (2005-05-06). Unsafe abortion. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Potts, Malcolm, & Campbell, Martha. (2002). History of contraception. Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 6, chp. 8. Retrieved 2005-01-25. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "potts" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 13.0 13.1 Devereux, G. (1967). A typological study of abortion in 350 primitive, ancient, and pre-industrial societies. Retrieved April 22, 2006. In Abortion in America: medical, psychiatric, legal, anthropological, and religious considerations. Boston: Beacon Press. Retrieved April 22, 2006.

- ↑ Lefkowitz, Mary R. & Fant, Maureen R. (1992). Women's life in Greece & Rome: a source book in translation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ Frontline. (2005) The Last Abortion Clinic.

- ↑ Glenc, F. (1974). Induced abortion - a historical outline. Polski Tygodnik Lekarski, 29 (45), 1957-8.

- ↑ Christopher Tietze and Sarah Lewit, "Abortion," Scientific American, 220 (1969), 21.

- ↑ Stark, Rodney (1996). The Rise of Christianity. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

- ↑ Contraception and Abortion in the Ancient Classical World. (1997). Ancient Roman Technology. Retrieved March 16, 2006, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill website.

- ↑ Devereux, G. (1976). Techniques of abortion. In A study of abortion in primitive societies. Revised edition. New York: International Universities Press. Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedyale - ↑ Obayashi, M. (1982). Historical background of the acceptance of induced abortion. Josanpu Zasshi 36(12), 1011-6. Retrieved April 12, 2006.

- ↑ Page Brookes, Anne. (1981). Mizuko kuyō and Japanese Buddhism.. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 8 (3-4), 119–47. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ↑ Mcfarlane, Alan. (2002). Abortion methods in England. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- ↑ Dyer, Frederick N. (1999). Pro-Life-Physician Horatio Robinson Storer: Your Ancestors, and You. Retrieved March 11, 2006.

- ↑ Beahen, William. (1986). Abortion and Infanticide in Western Canada 1874 to 1916: A Criminal Case Study. Historical Studies, 53, 53-70. Retrieved June 3, 2006.

- ↑ King, C.R. (1992). Abortion in nineteenth century America: a conflict between women and their physicians. Women's Health Issues, 2(1), 32-9. Retrieved June 4, 2006.

- ↑ Van de Warkle, Ely. (1870). The detection of criminal abortion. Journal of the Boston Historical Society, Vols 4 & 5.

- ↑ Hunton, R.B. (1977). Maori abortion practices in pre and early European New Zealand. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 86(602), 567-70. Retrieved June 4, 2006.

- ↑ Gluckman, L.K. (1981). Abortion in the nineteenth century Maori: a historical and ethnopsychiatric review. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 93(685), 384-6. Retrieved June 4, 2006.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 National Abortion Federation. (n.d.). Surgical Abortion:History and Overview. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- ↑ Gawande, Atul. (October 9, 2006.) "The Score: How Childbirth Went Industrial." The New Yorker. Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- ↑ "Destructive OB Forceps." (n.d.) Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- ↑ The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. (2005-11-02). "Public Opinion Supports Alito on Spousal Notification Even as It Favors Roe v. Wade." Pew Research Center Pollwatch. Retrieved 2006-03-01.

- ↑ Donohue, John J. and Levitt, Steven D. (2001). The impact of legalized abortion on crime.Quarterly Journal of Economics Retrieved 2006-02-11.

- ↑ Foote, Christopher L. and Goetz, Christopher F. (2005). Testing economic hypotheses with state-level data: a comment on Donohue and Levitt (2001). Working Papers, 05-15. Retrieved 2006-02-11.

- ↑ Donohue, John J. and Levitt, Steven D. (2006). Measurement error, legalized abortion, and the decline in crime: a response to Foote and Goetz (2005). Retrieved 2006-02-17, from University of Chicago, Initiative on Chicago Price Theory web site: ResponseToFooteGoetz2006.pdf.

- ↑ "Crime-Abortion Study Continues to Draw Pro-life Backlash." (1999-08-11). The Pro-Life Infonet. Retrieved 2006-02-17 from Ohio Roundtable Online Library.

- ↑ "Abortion and the Lower Crime Rate." (2000, January). St. Anthony Messenger. Retrieved 2006-02-17.

- ↑ Banister, Judith. (1999-03-16). Son Preference in Asia - Report of a Symposium. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ↑ Mutharayappa, Rangamuthia, Kim Choe, Minja, Arnold, Fred, & Roy, T.K. (1997). Son Preferences and Its Effect on Fertility in India. National Family Health Survey Subject Reports, Number 3. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ↑ Patel, Rita. (1996). The practice of sex selective abortion in India: may you be the mother of a hundred sons. Retrieved 2006-01-11, from University of North Carolina, University Center for International Studies web site: abortion.pdf.

- ↑ Sudha, S., & Irudaya Rajan, S. (1999). Female Demographic Disadvantage in India 1981-1991: Sex Selective Abortion, Female Infanticide and Excess Female Child Mortality. Retrieved 2006-01-12

- ↑ Reaney, Patricia. (2006-01-09). "Selective abortion blamed for India's missing girls." Reuters AlertNet. Retrieved 2006-01-09.

- ↑ Mudur, Ganapati. (2002). "India plans new legislation to prevent sex selection." British Medical Journal: News Roundup. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ↑ Graham, Maureen J., Larsen, Ulla, & Xu, Xiping. (1998). Son Preference in Anhui Province, China. International Family Planning Perspectives, 24 (2). Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ↑ Plafker, Ted. (2002-05-25). Sex selection in China sees 117 boys born for every 100 girls. British Medical Journal: News Roundup. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ↑ "China Bans Sex-selection Abortion." (2002-03-22). Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 World Health Organization. (2004). Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ↑ Salter, C., Johnson, H.B., and Hengen, N. (1997). Care for postabortion complications: saving women's lives. Population Reports, 25 (1). Retrieved 2006-02-22.

- ↑ World Health Organization. (1998). Address Unsafe Abortion. Retrieved 2006-03-01.

- ↑ Lord Ellenborough’s Act." (1998). The Abortion Law Homepage. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ↑ United Nations Population Division. (2002). Abortion Policies: A Global Review. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ↑ Eduction for Choice: More on UK abortion law[1]

- ↑ Ross, Jen. (September 12, 2006). "In Chile, free morning-after pills to teens." The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ↑ Gallardoi, Eduardo. (September 26, 2006). "Morning-After Pill Causes Furor in Chile." The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ↑ Surgical Abortion: History and Overview. National Abortion Federation. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Critchlow, Donald T. The Politics of Abortion and Birth Control in Historical Perspective (1996)

- Critchlow, Donald T. Intended Consequences: Birth Control, Abortion, and the Federal Government in Modern America (2001). ISBN 0195145933

- Garrow, David J. Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe V. Wade (1998). ISBN 0025427555

- Hull, N.E.H. Roe V. Wade: The Abortion Rights Controversy in American History (2001). Legal history. ISBN 0700611436

- Mohr, James C. Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy, 1800-1900 (1979). ISBN 0195026160

- Staggenborg. Suzanne. The Pro-Choice Movement: Organization and Activism in the Abortion Conflict (1994). ISBN 0195089251

- Rubin, Eva R. ed. The Abortion Controversy: A Documentary History (1994). ISBN 0313284768

- Hull, N.E.H. The Abortion Rights Controversy in America: A Legal Reader (2004). ISBN 0807855359

- Reagan, Leslie J. When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United State, 1867-1973 (1997). ISBN 0520216571

External links

- Text of the Roe v Wade decision Findlaw Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) (full text with links to cited material) Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- "Abortion Clinic:" a 1983 PBS Frontline episode. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health MedlinePlus encyclopedia Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- Abortion: All sides to the issue from the Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- Issue Guide on Abortion from Public Agenda Online Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- Abortion in Law, History & Religion Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- Surgical Instruments from Ancient Rome Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- Collection of Obstetrical Instruments Retrieved August 4, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.