Saint George

| Saint George | |

|---|---|

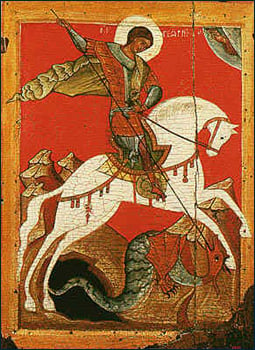

Painting by Gustave Moreau depicting Saint George slaying the dragon. | |

| Martyr | |

| Born | between ca. 275 and 281 C.E. in Nicomedia, Bithynia, Roman Empire |

| Died | April 23, 303 in Lydda, Iudaea, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | Anglicanism Eastern Orthodoxy Lutheranism Oriental Orthodoxy Roman Catholicism |

| Major shrine | Church of Saint George, Lod |

| Feast | April 23 |

| Attributes | Clothed as a soldier in a suit of armour or chain mail, often bearing a lance tipped by a cross, riding a white horse, often slaying a dragon. In the West he is shown with Saint George's Cross emblazoned on his armour, or shield or banner. |

| Patronage | agricultural workers; Amersfoort, Netherlands; Aragon; archers; armourers; Beirut, Lebanon; Bulgaria; butchers; Cappadocia; Catalonia; cavalry; chivalry; Constantinople; Corinthians (Brazilian football team); Crusaders; England; equestrians; Ethiopia; farmers; Ferrara; field workers; Genoa; Georgia; Gozo; Greece; Haldern, Germany; Heide; herpes; horsemen; horses; husbandmen; knights; lepers and leprosy; Lithuania; Lod; Malta; Modica, Sicily; Moscow; Order of the Garter; Palestine; Palestinian Christians; Piran; plague; Portugal; Portuguese Army; Portuguese Navy; Ptuj, Slovenia; Reggio Calabria; riders; saddle makers; Scouts; sheep; shepherds; skin diseases; soldiers; syphilis; Teutonic Knights[1] |

Saint George (ca. 275/281 ‚Äď April 23, 303 C.E.), also known as George of Lydda, is one of the most venerated saints in the Anglican Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Eastern Catholic Churches. Enlisted as a Roman soldier in the Guard of Emperor Diocletian, he was martyred for his beliefs and became regarded as one of the most prominent military saints. Christian folklore also honours him through the popular tale of Saint George and the Dragon.

In Christian hagiography, Saint George is the patron saint of Aragon, Catalonia, England, Ethiopia, Georgia, Greece, Lithuania, Palestine, Portugal, and Russia, as well as the cities of Amersfoort, Beirut, Bteghrine, C√°ceres, Ferrara, Freiburg, Genoa, Ljubljana, Gozo, Pomorie, Qormi, Lod and Moscow, as well as a wide range of professions, organizations and disease sufferers.

Saint George is particularly honored by both the Eastern Orthodox Church and in Oriental Orthodoxy where his major feast day is on April 23 (Julian Calendar). He is also honored in Roman Catholicism but not to the same extent as in the Orthodox churches. Due to the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, he was removed from the Universal Calendar with the proviso that he could be honored in local calendars. However, in 2000, Pope John Paul II restored Saint George to the Universal Calendar, and he appears in Missals as the English Patron Saint. He is also listed as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers in Roman Catholicism.

Life

George (meaning "worker of the land") was born to a Christian noble family during the late third century between about 275 C.E. and 285 C.E., in Lydia Palestine. His father Geronzio was a Roman army official from Cappadocia and his mother from Palestine. They were both Christians and from noble families and the child was raised with Christian beliefs. At the age of 14, George lost his father; a few years later, George's mother Policronia died. George subsequently decided to go to Nicomedeia, the imperial city of that time, and present himself to Emperor Diocletian to apply for a career as a soldier. Diocletian welcomed him with open arms, as he had known his father Geronzio‚ÄĒone of his finest soldiers. By his late twenties, George was promoted to the rank of Tribunus and stationed as an imperial guard of the Emperor at Nicomedeia.

In the year 302 C.E., Diocletian (influenced by Galerius) issued an edict that every Christian soldier in the army should be arrested and every other soldier should offer a sacrifice to the Pagan gods. George, however, objected and with the courage of his faith approached the Emperor and ruler. Diocletian was upset, not wanting to lose his best Tribune and the son of his best official, Geronzio. George loudly renounced the Emperor's edict, and in front his fellow soldiers and Tribunes he claimed himself to be a Christian and declared his worship of Jesus Christ. Diocletian attempted to convert George, even offering gifts of land, money and slaves if he made a sacrifice to the Pagan gods. The Emperor made many offers, but George never accepted.

Recognizing the futility of his efforts, Diocletian was left with no choice but to have him executed for his refusal. Before the execution George gave his wealth to the poor and prepared himself. After various torture sessions, including laceration on a wheel of swords in which he was miraculously resuscitated three times, George was executed by decapitation before Nicomedia's city wall, on April 23, 303. A witness of his suffering convinced Empress Alexandra and Athanasius, a pagan priest, to become Christians as well, and so they joined George in martyrdom. His body was returned to Lydda for burial, where Christians soon came to honor him as a martyr.

Veneration

A church built in Lydda during the reign of Constantine I (reigned 306‚Äď337), was consecrated to "a man of the highest distinction," according to the church history of Eusebius of Caesarea; the name of the patron was not disclosed, but later he was asserted to have been George. The church was destroyed in 1010 but was later rebuilt and dedicated to Saint George by the Crusaders. In 1191, and during the conflict known as the Third Crusade (1189‚Äď1192), the church was again destroyed by the forces of Saladin, Sultan of the Ayyubid dynasty (reigned 1171‚Äď1193). A new church was erected in 1872 and is still standing.

During the fourth century the veneration of George spread from Palestine through Lebanon to the rest of the Eastern Roman Empire‚ÄĒthough the martyr is not mentioned in the Syriac Breviarium[2]‚ÄĒand Georgia. In Georgia, the feast day on November 23 is credited to Saint Nino of Cappadocia, who in Georgian hagiography is a relative of Saint George, credited with bringing Christianity to the Georgians in the fourth century. By the fifth century, the cult of Saint George had reached the Western Roman Empire as well: in 494, George was canonised as a saint by Pope Gelasius I, among those "whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose acts are known only to [God]."

In England, the earliest dedication to George, who was mentioned among the martyrs by Bede (ca. 672 or 673 ‚Äď May 27, 735), is a church at Fordington, Dorset, that is mentioned in the will of Alfred the Great. "Saint George and his feast day began to gain more widespread fame among all Europeans, however, from the time of the Crusades."[3] An apparition of George heartened the Franks at the siege of Antioch, 1098, and made a similar appearance the following year at Jerusalem. Chivalric military Order of St. George were established in Aragon (1201), Genoa, Hungary, and by Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor,[4] and Edward III put his Order of the Garter under the banner of Saint George. In England, the Synod of Oxford, 1222 declared St. George's Day a feast day in the kingdom of England. The chronicler Froissart observed the English invoking Saint George as a battle cry on several occasions during the Hundred Years' War. In his rise as a national saint, George was aided by the very fact that the saint had no legendary connection with England, and no specifically localized shrine, as of Thomas Becket at Canterbury: "Consequently, numerous shrines were established during the late fifteenth century," Muriel C. McClendon has written,[5] "and his did not become closely identified with a particular occupation or with the cure of a specific malady."

The establishment of George as a popular saint and protective giant[6] in the West that had captured the medieval imagination was codified by the official elevation of his feast to a festum duplex at a church council in 1415, on the date that had become associated with his martyrdom, April 23. There was wide latitude from community to community in celebration of the day across late medieval and early modern England,[7] and no uniform "national" celebration elsewhere, a token of the popular and vernacular nature of George's cultus and its local horizons, supported by a local guild or confraternity under George's protection, or the dedication of a local church. When the Reformation in England severely curtailed the saints' days in the calendar, Saint George's Day was among the holidays that continued to be observed.

Legend of Saint George and the Dragon

Saint George is not commemorated in any early vita or acta that would have some merit as reflecting history and cannot be accounted a historical individual.[8] Chief among the late sources is the Golden Legend, which remains the most familiar version in English owing to William Caxton's fifteenth century translation.

The traditional legend offers a historicized narration of George's encounter with his dragon: see "St. George and the Dragon" below. The modern legend that follows is synthesized from early and late hagiographical sources, omitting the more fantastical episodes, to narrate a purely human military career in closer harmony with modern expectations of reality.

The episode of Saint George and the Dragon was a myth[9] brought back with the Crusaders and retold with the courtly appurtenances belonging to the genre of Romance (Loomis; Whatley). The earliest known depiction of the mytheme is from early eleventh-century Cappadocia (Whatley), (in the iconography of the Eastern Orthodox Church, George had been depicted as a soldier since at least the seventh century); the earliest known surviving narrative text is an eleventh-century Georgian text (Whatley).

In the fully-developed Western version, a dragon makes its nest at the spring that provides water for the city of "Silene" (perhaps modern Cyrene) in Libya or the city of Lydda, depending on the source. Consequently, the citizens have to dislodge the dragon from its nest for a time, in order to collect water. To do so, each day they offer the dragon at first a sheep, and if no sheep can be found, then a maiden must go instead of the sheep. The victim is chosen by drawing lots. One day, this happens to be the princess. The monarch begs for her life with no result. She is offered to the dragon, but there appears the saint on his travels. He faces the dragon, protects himself with the sign of the cross,[10] slays it and rescues the princess. The grateful citizens abandon their ancestral paganism and convert to Christianity.

The dragon motif was first combined with the standardized Passio Georgii in Vincent of Beauvais' encyclopedic Speculum historale and then in Jacobus de Voragine, Golden Legend, which guaranteed its popularity in the later Middle Ages as a literary and pictorial subject (Whatley).

The parallels with Perseus and Andromeda are inescapable. In the allegorical reading, the dragon embodies a suppressed pagan cult.[11] The story has roots that predate Christianity. Examples such as Sabazios, the sky father, who was usually depicted riding on horseback, and Zeus's defeat of Typhon the Titan in Greek mythology, along with examples from Germanic and Vedic traditions, have led a number of historians, such as Loomis, to suggest that George is a Christianized version of older deities in Indo-European culture.

In the medieval romances, the lance with which Saint George slew the dragon was called Ascalon, named after the city of Ashkelon in Israel.[12]

Iconography

Saint George is most commonly depicted in early icons, mosaics and frescos wearing armour contemporary with the depiction, executed in gilding and silver color, intended to identify him as a Roman soldier. After the Fall of Constantinople and the association of Saint George with the Crusades, he is more often portrayed mounted upon a white horse.

At the same time Saint George began to be associated with Saint Demetrius, another early soldier saint. When the two saints are portrayed together mounted upon horses, they may be likened to earthly manifestations of the archangels Michael and Gabriel. Saint George is always depicted in Eastern traditions upon a white horse and Saint Demetrius on a red horse[13] Saint George can also be identified in the act of spearing a dragon, unlike Demetrius, who is sometimes shown spearing a human figure, understood to represent Maximian.

The "Colours of Saint George," or Saint George's Cross) are a white flag with a red cross, frequently borne by entities over which he is patron (e.g. England, Georgia, Liguria, Catalonia, etc.).

The origin of the Saint George's Cross came from the earlier plain white tunics worn by the early Crusaders.

During the early second millennium, George came to be seen as the model of chivalry, and during this time was depicted in works of literature, such as the medieval romances.

Local Traditions

Belgium

In Mons, Belgium,[14] Saint Georges is honored each spring at Trinity Sunday. In the heart of the city, a reenactment (known as the ‚ÄúCombat dit Lume√ßon‚ÄĚ) of the fight between Saint Georges and the dragon is played by 46 actors.[15] According to the tradition, the residents of Mons try to get a piece of the dragon during the fight. This will bring luck for one year to the ones succeeding in this challenge. This event is part of the annual Ducasse and is attended by thousands of people.

Brazil

As part of the Portuguese Empire, Brazil inherited the devotion to Saint George, as patron saint of Portugal.

In the religious traditions of the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé and Umbanda, Ogum (as this Yoruba divinity is known in the Portuguese language) is often identified with Saint George in many regions of the country, being widely celebrated by both religions' followers. Popular devotion to Saint George is very strong in Rio de Janeiro, where the saint vies in popularity with the city's official patron Saint Sebastian, both saints' feast days being local holidays.

Bulgaria

Saint George is praised by the Bulgarians as "liberator of captives, and defender of the poor, physician of the sick." For centuries he has been considered by the Bulgarians as their protector. Possibly the most celebrated name day in the country, Saint George's Day (–ď–Ķ—Ä–≥—Ć–ĺ–≤–ī–Ķ–Ĺ, Gergyovden) is a public holiday that takes place on May 6 every year. A common ritual is to prepare and eat a whole lamb. Saint George is the patron saint of farmers and shepherds.

Saint George's Day is also the "Day of the Bulgarian Army" (made official with a decree of Knyaz Alexander of Bulgaria on January 9, 1880, and parades are organized in the capital Sofia to present the best of the army's equipment and manpower.

England

Traces of the cult of Saint George predate the Norman Conquest, in ninth-century liturgy used at Durham Cathedral, in a tenth-century Anglo-Saxon martyrology, and in dedications to Saint George at Fordingham, Dorset, at Thetford, Southwark and Doncaster. He received further impetus when the crusaders returned from the Holy Land in the twelfth century. King Edward III of England (reigned 1327 ‚Äď 1377) was known for promoting the codes of knighthood and in 1348 founded the Order of the Garter. During his reign, George came to be recognized as the patron saint of the English monarchy; prior to this, Edmund the Martyr (841 ‚Äď 869) of East Anglia had been considered the patron saint of England, although his veneration had waned since the time of the Norman Conquest, and his cult was partly eclipsed by that of Edward the Confessor. Edward dedicated the chapel at Windsor Castle to the soldier saint who represented the knightly values of chivalry which he so much admired, and the Garter ceremony takes place there every year. In the sixteenth century, William Shakespeare firmly placed Saint George within the national conscience in his play Henry V in which the English troops are rallied with the cry ‚ÄúGod for Harry, England and Saint George,‚ÄĚ and Edmund Spenser included Saint George (Redcross Knight) as a central figure in his epic poem The Faerie Queen.

With the revival of Scottish and Welsh nationalism, there has been renewed interest within England in Saint George, whose memory had been in abeyance for many years. This is most evident in the Saint George's flags which now have replaced Union Jacks in stadiums where English sports teams compete. St George’s Day is celebrated each year in London with a day of celebration run by the Greater London Authority and the London Mayor. The City of Salisbury holds an annual Saint George’s Day pageant, the origins of which are believed to go back to the thirteenth century.[1][2] Retrieved February 6, 2009. [3][4] Retrieved February 6, 2009. [5][6] [7] Retrieved February 6, 2009.

Georgia

Saint George is a patron saint of Georgia. According to Georgian author Enriko Gabisashvili, Saint George is most venerated in the nation of Georgia. An eighteenth century Georgian geographer and historian Vakhushti Bagrationi wrote that there are 365 Orthodox churches in Georgia named after Saint George according to the number of days in one year.[16] There are indeed many churches in Georgia named after the Saint and Alaverdi Monastery is one of the largest.

The Georgian Orthodox Church commemorates Saint George's day twice a year, on May 6 (O.C. April 23) and November 23. The feast day in November was instituted by Saint Nino of Cappadocia, who was credited with bringing Christianity to the land of Georgia in the fourth century. She was from Cappadocia, like Saint George, and was his relative. This feast day is unique to Georgia and it is the day of Saint George's martyrdom.

There are also many folk traditions in Georgia that vary from Georgian Orthodox Church rules, because they portray the Saint differently than the Church does and show the veneration of Saint George in common people of Georgia. In most folk tales Saint George is venerated very highly, almost as much as Jesus Christ himself. In the province of Kakheti, there is an icon of Saint George known as "White George," also seen on the current Coat of Arms of Georgia. The region of Pshavi have icons of known as the "Cuppola St. George" and "Lashari St. George." The Khevsureti region has "Kakhmati," "Gudani," and "Sanebi" icons dedicated to the Saint. The Pshavs and Khevsurs, during the Middle Ages used to refer to Saint George almost as much as praying to God and the Blessed Virgin Mary. Another notable icon is known as the "Lomisi Saint George" which can be found in the Mtiuleti and Khevi provinces of Georgia.[16]

India

Churches and shrines dedicated to Saint George are found all over India, especially among those Indian Christians practicing Oriental Orthodoxy and Eastern Catholicism. In particular, in the region of Kerala, on the banks of the Kodoor river in the district of Kottayam, the village of Puthupally is famous for the sixteenth-century Saint George Syrian Orthodox Patriarchal Church. The feast held on the first Saturday and Sunday during the month of May attracts pilgrims from all over Kerala. It is one of the famous pilgrim centers of Saint George, in India.

Italy

In Italy, he is one of the Patron Saints of Genoa, as well as of Ferrara and Reggio Calabria. The historical bank that was the backbone of the Republic of Genoa, "Repubblica Marinara di Genova," was dedicated to Saint George, "Banco di San Giorgio." The power of the Repubblica passing from commerce to banking, Genoa lent money to all the European countries and sovereigns, so the power of the "Repubblica" was identified with its patron saint.

Lebanon

Saint George is the patron saint of Beirut, Lebanon.[17] Many bays around Lebanon are named after Saint George, particularly the Saint George Bay in Beirut. The Saint George Bay in Beirut is believed to be the place where the dragon lived and where it was slain.[18] In Lebanon, Saint George is believed to have cleaned off his spear at a massive rocky cave running into the hillside and overlooking the beautiful Jounieh Bay. Others argue it is at the Bay of Tabarja. The waters of both caves are believed to have miraculous powers for healing ailing children.[18]

An ancient gilded icon of Saint George at the Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Beirut has been a major attraction for believers: Greek Orthodox, Copts, Catholics, Maronites and some Muslims, for many centuries.[18]

Malta

Saint George is also one of the patron saints of the Mediterranean islands of Malta and Gozo. In a battle between the Maltese and the Moors, Saint George was alleged to have been seen with Saint Paul and Saint Agata, protecting the Maltese. Two parishes are dedicated to Saint George in Malta and Gozo, the Parish of Qormi, Malta and the Parish of Victoria, Gozo. Besides being the patron of Victoria where a splendid basilica is dedicated to him, St George is the protector of the island Gozo. He is also the patron saint of the village of Qormi. Many churches in the Maltese Islands, have also altars dedicated to this saint.

The George Cross was awarded to the entire island of Malta for their courage and endurance during World War II. In a letter dated April 15, 1942, King George VI, stated: "To honour her brave people, I award the George Cross to the Island Fortress of Malta to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history." Since that time, the George Cross has appeared on the Flag of Malta.

Palestine

The Feast of Saint George is celebrated by both the Palestinian Christians, whose patron saint is George, and many Muslims, especially in the areas around Bethlehem where he is believed to have lived in his childhood. Christian houses can be identified with a stone-engraved picture of the saint (known as Mar Jiries) in front of their homes for his protection.

In the town of Beit Jala, just west of Bethlehem stands a statue of Saint George carved of stone depicting the saint on his horse while fighting the dragon. The statue stands in the town's main square.

There is also a mid-sized town named al-Khader in his honor. The town contains a sixteenth century monastery known as the Monastery of Saint George. In the Wadi Qelt near Jericho stands the Saint George's Monastery.

Portugal

Apparently the English crusaders that helped King Afonso Henriques in the conquest of Lisbon in 1147, introduced the major devotion to Saint George in Portugal.

Nevertheless, it was not until the time of King Afonso IV that the use of São Jorge ! (Saint George) as battle cry, substituted the former Sant'Iago ! (Saint James).

Nuno √Ālvares Pereira, Constable of Portugal, considered Saint George the leader of the Portuguese victory in the battle of Aljubarrota. King John I was also a devotee of the Saint and was in his reign that Saint George replaced Saint James as the main patron saint of Portugal. In 1387, he ordered that its image on horse was carried in Corpus Cristi procession, tradition that also extended, later, to Brazil.

Russia

Modern Russians interpret the icon not as a killing but as a struggle, against ourselves and the evil among us. The dragon never dies but the saint persists with his horse (will and support of the people) and his spear (technical means). This is a useful symbol for modern technocrats, especially in fields such as public health.

Serbia

"ńźurńĎevdan" (Serbian: –ā—É—Ä—í–Ķ–≤–ī–į–Ĺ - George's day) is a Serbian religious holiday, celebrated on April 23 by the Julian calendar (May 6 by Gregorian calendar), which is the feast of Saint George and a very important Slava. He is one of the most important Christian saints in Orthodox churches. This holiday is attached to the tradition of celebrating the beginning of spring. Christian synaxaria hold that St. George was a martyr who died for his faith. On icons, he is usually depicted as a man riding a horse and killing a dragon. ńźurńĎevdan is celebrated all over the Serbian diaspora but mainly in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the Serbian Language St. George is called Sveti ńźorńĎe (Serbian Cyrillic: –°–≤–Ķ—ā–ł –ā–ĺ—Ä—í–Ķ).

Spain

In Spain, Saint George also came to be considered as the patron saint of the medieval Crown of Aragon, the territory of four current autonomous communities of Spain: Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands. Today, Saint George is the saint patron of both Aragon and Catalonia, as well as the saint patron of historically important Spanish towns such as C√°ceres or Alcoy (Spanish language: San Jorge, Catalan language: Sant Jordi, Aragonese language: San Jorge).

His feast date, April 23, is one of the most important holidays in Catalonia, where it is traditional to give a present to the loved one; red roses for women and books for men. In Aragon, it is a public holiday, celebrated as the Day of Aragon. It is also a public holiday in Castile and Leon, where the day commemorates the defeat at the Revolt of the Comuneros.

Impact

As one of the most widely venerated of all the Christian saints throughout the different branches of Christianity, St. George is particularly notable as an figure of ecumenical significance since, like Jesus himself, St. George continues to be honoured by diverse churches around the world. He has become the patron saint of many countries, the focus of much Christian art and sculpture, as well as the focus of popular medieval legends. He was a particularly prominent saint during the Crusades and the Middle Ages, where he was championed for his military exploits and his courage against enemies, particularly the feared dragon.

Today, St. George still plays an important role in the popular culture of England as his cross adorns their traditional flag, which is still used by English football (soccer) teams. He also remains a popular saint in the religious practice of Eastern Orthodox countries.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Saint George Patron Saints Index. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ‚ÜĎ Alban Butler, Butler's Lives of the Saints (Liturgical Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0814629031).

- ‚ÜĎ Muriel C. McClendon, "A Moveable Feast: Saint George's Day Celebrations and Religious Change in Early Modern England" The Journal of British Studies 38 (1)(January 1999): 6.

- ‚ÜĎ David Scott Fox, Saint George: The Saint with Three Faces (Kensal Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0946041138), 59-63, 98-123.

- ‚ÜĎ McClendon, 1999, 10.

- ‚ÜĎ Erasmus, in The Praise of Folly (1509, printed 1511) remarked "The Christians have now their gigantic Saint George, as well as the pagans had their Hercules."

- ‚ÜĎ McClendon, 1999, 1-27.

- ‚ÜĎ The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge omitted Saint George.

- ‚ÜĎ Robertson, The Medieval Saints' Lives (pp 51-52) suggested that the dragon motif was transferred to the George legend from that of his fellow soldier saint, Saint Theodore Tiro.

- ‚ÜĎ "He drew out his sword and garnished him with the sign of the cross, and rose hardily against the dragon which came toward him, and smote him with his spear and hurt him sore, and threw him to the ground," according to Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: or Lives of the Saints as Englished by William Caxton, F.S. Ellis, ed. (London, 1900), vol. III:123-45), quotation p. 128.

- ‚ÜĎ Loomis 1948:65 and notes 111-17, giving references to other saints' encounters with dragons. "To Loomis's list might be added the stories of Martha ‚Ķ and Silvester, which is vigorously summarized (from a fifth-century version of the Actus Silvestri) by the early English writer, Aldhelm, abbot of Malmesbury (639-709), in his De Virginitate (see Aldhelm: The Prose Works, pp. 82-83). On dragons and saints, see Christine Rauer, Beowulf and the Dragon (D.S. Brewer, 2000, ISBN 978-0859915922). Saint Mercurialis, the first bishop of the city of Forl√¨, in Romagna, is often portrayed in the act of killing a dragon.

- ‚ÜĎ Incidentally, the name Ascalon was used by Winston Churchill for his personal aircraft during World War II, according to records at Bletchley Park.

- ‚ÜĎ The red pigment may appear black if it has bitumenized.

- ‚ÜĎ Mons.be - Site officiel de la Ville de Mons Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ‚ÜĎ Doudou - Mons - Le Doudou, Ducasse Rituelle de Mons - La Procession du Car d'Or et le Combat dit "Lume√ßon" BLOG doudou.org. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ‚ÜĎ 16.0 16.1 Enriko Gabidzashvili, Saint George: In Ancient Georgian Literature. (Tbilisi, Georgia: Armazi, 1991).

- ‚ÜĎ St George comes under fire BBC News, Feb. 21, 2002, Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ‚ÜĎ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Saudi Aramco World: St. George The Ubiquitous saudiaramcoworld.com. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aldhelm. Aldhelm: The Prose Works. Translated by Michael Lapidge and Michael Herren. D.S.Brewer, 2009. ISBN 978-1843841999

- Brooks, E.W. Acts of Saint George in series Analecta Gorgiana, 8. Gorgias Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1593334857

- Butler, Alban. Butler's Lives of the Saints. Liturgical Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0814629031

- Fox, David Scott. Saint George: The Saint with Three Faces. Kensal Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0946041138

- Gabidzashvili, Enriko. Saint George: In Ancient Georgian Literature. Tbilisi, Georgia: Armazi, 1991.

- Loomis, C. Grant. White Magic, An Introduction to the Folklore of Christian Legend. Cambridge: Medieval Society of America, 1948. ISBN 978-1436712859

- McClendon, Muriel C. "A Moveable Feast: Saint George's Day Celebrations and Religious Change in Early Modern England." The Journal of British Studies 38(1) (January 1999): 1-27.

- Natsheh, Yusuf. "Architectural survey," in Ottoman Jerusalem: The Living City 1517-1917. Al Tajir-World of Islam Trust, 2000. ISBN 978-1901435030

- Rauer, Christine. Beowulf and the Dragon. D.S. Brewer, 2000. ISBN 978-0859915922

- de Voragine, Jacobus. The Golden Legend: or Lives of the Saints as Englished by William Caxton. London: Dent, 1900. ASIN B0026JSEU6

- Whatley, E. Gordon, Anne B. Thompson, and Robert K. Upchurch (eds.). Saints' Lives In Middle English Collections. Western Michigan University Medieval, 2005. ISBN 978-1580440899

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.