Allegory

An allegory (from Greek αλλος, allos, "other," and αγορευειν, agoreuein, "to speak in public") is a symbolic, figurative mode of representation of abstract ideas and principles. An allegory is generally treated as a figure of rhetoric, but it may be addressed in visual forms such as painting, sculpture or some forms of mimetic art.

Though it is similar to other rhetorical comparisons, an allegory is longer and more detailed than a metaphor and often appeals to the imagination, whereas an analogy appeals to reason. The fable or parable is a short allegory with one definite moral.

The allegory is one of the most popular narrative forms in literature, philosophy, and various other areas. In Psalm 80:19-17 in the Old Testament, for example, the history of Israel is depicted in the growth of a vine. In philosophy, Plato's allegory of the cave and his chariot allegory are the best known classic examples.

Allegories in Scriptures, literature, and arts

Hebrew scriptures

The Hebrew scriptures contains various allegories, one of the most beautiful being the depiction of the history of Israel as the growth of a vine in Psalm 80:19-17. In the Rabbinic tradition, fully-developed allegorical readings were applied to every text with every detail of the narrative given an emblematic reading. This tradition was inherited by Christian writers, for whom allegorical similitudes are the basis of exegesis, the origin of hermeneutics. The late Jewish and Early Christian visionary Apocalyptic literature, with its base in the Book of Daniel, presents allegorical figures, of which the Whore of Babylon and the Beast of Revelation are the most familiar.

Classical literature

In classical literature a few of the best known allegories are the cave of shadowy representations in Plato's Republic (Book VII), the story of the stomach and its members in the speech of Menenius Agrippa (Livy ii. 32), and the several that occur in Ovid's Metamorphoses. In Late Antiquity, Martianus Capella organized all the information a fifth-century upper-class male needed to know into a widely read allegory of the wedding of Mercury and Philologia, with the seven liberal arts as guests. In the late fifteenth century, the enigmatic Hypnerotomachia, with its elaborate woodcut illustrations, shows the influence of themed pageants and masques on contemporary allegorical representation.

Allegory in the Middle Ages

The allegory in the Middle Ages was a vital element in the synthesis of Biblical and Classical traditions into what would become recognizable as Medieval culture. People of the Middle Ages consciously drew from the cultural legacies of the ancient world in shaping their institutions and ideas, and so the use of allegories in Medieval literature and Medieval art was a prime mover for the synthesis and transformational continuity between the ancient world and the "new" Christian world. People of the Middle Ages did not perceive the same break between themselves and their classical forbears that modern observers see; rather, the use of allegories became a synthesizing agent that helped to connect the classical and medieval traditions.

Some elaborate and successful examples of allegory are found in the following works, arranged in approximately chronological order:

- Aesop – Fables

- Plato – The Republic (Allegory of the Cave) (see below)

- Plato – Phaedrus (Chariot Allegory) (see below)

- Book of Revelation

- Martianus Capella – De nuptiis philologiæ et Mercurii

- The Romance of the Rose

- Piers Plowman

- The Pearl

- Dante Alighieri – The Divine Comedy

- Edmund Spenser – The Faerie Queene

- John Bunyan – Pilgrim's Progress

- Jean de La Fontaine – Fables

- Jonathan Swift – A Tale of a Tub

- Joseph Addison – Vision of Mirza

Modern literatures, films, and arts

Modern allegories in fiction tend to operate under constraints of modern requirements for verisimilitude within conventional expectations of realism. Works of fiction with strong allegorical overtones include:

- William Golding – Lord of the Flies

- George Orwell – Animal Farm

- Arthur Miller – The Crucible

- Philip Pullman – His Dark Materials

Hualing Nieh: Mulberry and Peach Allegorical films include:

- Fritz Lang's Metropolis

- Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal

- El Topo etc.

Allegorical artworks include:

- Sandro Botticelli – La Primavera (Allegory of Spring)

- Albrecht Dürer – Melancholia I

- Artemisia Gentileschi – Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting; Allegory of Inclination

- Jan Vermeer – The Allegory of Painting

Plato's Allegory of the cave

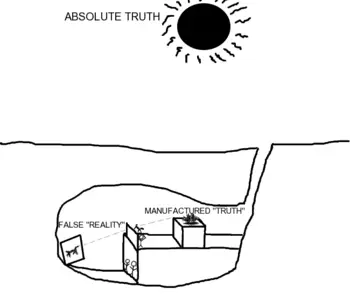

The Allegory of the Cave is an allegory used by the Greek philosopher Plato in his work The Republic. The allegory of the cave is told and then interpreted by the character Socrates at the beginning of Book 7 (514a–520a). It is related to Plato's metaphor of the sun (507b–509c) and the analogy of the divided line (509d–513e) which immediately precede it at the end of Book 6. Allegories are summarized in the viewpoint of dialectic at the end of book VII and VIII (531d-534e). The allegory of the cave is also commonly known as Myth of the Cave, Metaphor of the Cave or the Parable of the Cave.

Plot

Imagine prisoners who have been chained since their childhood deep inside a cave: not only are their arms and legs unmovable because of chains; their heads are chained in one direction as well so that their gaze is fixed on a wall.

Behind the prisoners is an enormous fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway, along which puppets of various animals, plants, and other things are moved along. The puppets cast shadows on the wall, and the prisoners watch these shadows. When one of the puppet-carriers speaks, an echo against the wall causes the prisoners to believe that the words come from the shadows.

The prisoners engage in what appears to be a game: naming the shapes as they come by. This, however, is the only reality that they know, even though they are seeing merely shadows of objects. They are thus conditioned to judge the quality of one another by their skill in quickly naming the shapes and dislike those who play poorly.

Suppose a prisoner is released and compelled to stand up and turn around. At that moment his eyes will be blinded by the sunlight coming into the cave from its entrance, and the shapes passing by will appear less real than their shadows.

The last object he would be able to see is the sun, which, in time, he would learn to see as the object that provides the seasons and the courses of the year, presides over all things in the visible region, and is in some way the cause of all these things that he has seen.

(This part of the allegory closely relates to Plato's metaphor of the sun which occurs near the end of The Republic, Book VI.)[1]

Once enlightened, so to speak, the freed prisoner would not want to return to the cave to free "his fellow bondsmen," but would be compelled to do so. The prisoner's eyes, adjusted to the bright world above, would function poorly in the dark cave. The other prisoners would freely criticize and reject him. (The Republic bk. VII, 516b-c; trans. Paul Shorey).[2]

Interpretation

Plato believed that truth was obtained from looking at universals in order to gain an understanding of experience. In other words, humans had to travel from the visible realm of image-making and objects of sense, to the intelligible, or invisible, realm of reasoning and understanding. "The Allegory of the Cave" symbolizes this trek and how it would look to those still in a lower realm. According to the allegory, humans are all prisoners and the tangible world is our cave. The things we perceive as real are actually just shadows on a wall. Finally, just as the escaped prisoner ascends into the light of the sun, we amass knowledge and ascend into the light of true reality, where ideas in our minds can help us understand the form of 'The Good'.

Plato's Chariot Allegory

Plato, in his dialogue, Phaedrus (sections 246a - 254e), uses the Chariot Allegory to explain his view of the human soul. He does this in the dialogue through the character Socrates, who uses it in a discussion of the merit of Love as "divine madness."

The chariot

Plato describes a Charioteer driving a chariot pulled by two horses. One horse is white and long necked, well bred, well behaved, and runs without a whip. The other is black, short-necked, badly bred, and troublesome.

The Charioteer represents intellect, reason, or the part of the soul that must guide the soul to truth; the white horse represents rational or moral impulse or the positive part of passionate nature (e.g., righteous indignation); the black horse represents the soul's irrational passions, appetites, or concupiscent nature. The Charioteer directs the entire chariot/soul to try to stop the horses from going different ways and proceed towards enlightenment.

The journey

Plato describes a "great circuit" which souls make as they follow the gods in the path of enlightenment. Those few souls which are fully enlightened are able to see the world of the forms in all its glory. Some souls have difficulty controlling the black horse, even with the help of the white horse. They may bob up into the world of the forms, but at other times enlightenment is hidden from them. If overcome by the black horse or forgetfulness, the soul loses its wings and is pulled down to earth.

Should that happen, the soul is incarnated into one of nine kinds of person, according to how much truth it beheld. In order of decreasing levels of truth seen, the categories are: (1) philosophers, lovers of beauty, men of culture, or those dedicated to love; (2) law-abiding kings or civic leaders; (3) politicians, estate-managers or buisinessmen; (4) ones who specialize in bodily health; (5) prophets or mystery cult participants; (6) poets or imitative artists; (7) craftsmen or farmers; (8) sophists or demagogues; and (9) tyrants.[3]

One need not suppose that Plato intended this as a literal discussion of metempsychosis or reincarnation.[4]

Allegorical sculpture

Allegorical sculpture refers to sculptures that symbolize and particularly personify abstract ideas.

Common in the Western world, for example, are statues of 'Justice': a female figure traditionally holding scales in one hand, as a symbol of her weighing issues and arguments, and a Sword of Justice in the other. She also wears a blindfold to represent her impartiality. This approach of using human form, posture, gesture and clothing to convey social values may be seen in funerary art as early as 1580. They were used in Renaissance monuments when patron saints became unacceptable. Particularly popular were the Four cardinal virtues and the Three Christian virtues, but others such as fame, victory and time are also represented. Allegorical sculptures fully developed under the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. It is usually associated with Victorian art, and is most commonly found in works from around 1900.

Notable allegorical sculptures

- The Statue of Liberty

- The figures of the four continents and four arts and sciences surrounding the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens.

- Statue of Justice on the Old Bailey in London.

- The Four cardinal virtues, by Maximilian Colt, on the monument to Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury in Bishop's Hatfield Church in the English county of Hertfordshire.

- In Pan-American Exposition of 1901 in Buffalo, New York had an extensive scheme of allegorical sculpture programmed by Karl Bitter.

- The allegorical group on top of Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan, carved by the French sculptor Jules Felix Couton in 1912, represents the Roman gods, Hercules (strength), Mercury (speed) and Minerva (wisdom), and collectively represents 'Transportation'.

Notes

- ↑ Plato and B. Jowett, Plato's The Republic. New York: The Modern library, 1941, OCLC: 964319

- ↑ Plato and P. Shorey, The Republic. London: W. Heinemann, ltd., 1930.

- ↑ Phaedrus by Plato, Project Gutenberg. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ↑ Republic, Classic technology center, AbleMedia. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chaucer, Geoffrey. Lyric and Allegory. The Poetry bookshelf. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1971. ISBN 0389040711 ISBN 9780389040712

- English Institute, and Stephen Greenblatt. Allegory and Representation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981. ISBN 080182642X ISBN 9780801826429

- Fletcher, Angus. Allegory, The Theory of a Symbolic Mode. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1964.

- Frye, Northrop. 1957. Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Langmuir, Erika. Allegory. London: National Gallery Publications, 1997. ISBN 1857091663 ISBN 9781857091663 ISBN 0300073208 ISBN 9780300073201

- MacQueen, John. Allegory. The Critical idiom, 14. London: Methuen, 1970. ISBN 0416080405 ISBN 9780416080407

- Whitman, Jon. Interpretation and Allegory Antiquity to the Modern Period. Brill's studies in intellectual history, v. 101. Leiden: Brill, 2000. ISBN 1417536500 ISBN 9781417536504

External links

All links retrieved July 20, 2023.

- Good brief definition of Allegory

- Allegory in Literary history Dictionary of the History of Ideas.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Allegory history

- Allegory history

- Allegory_of_the_cave history

- Chariot_Allegory history

- Allegory_in_the_Middle_Ages history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.