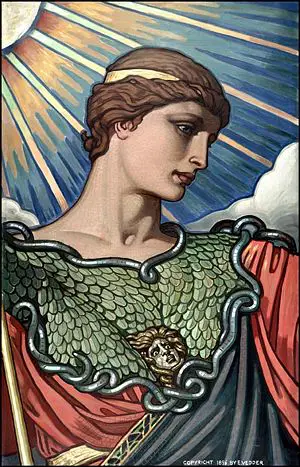

Minerva

Minerva was the ancient Roman goddess of wisdom and war. Her areas of patronage included crafts, poetry, medicine, and music. Like many of the figures of the Roman pantheon, some of Minerva's characteristics were adapted from the Greek tradition. Eventually, she became equated with Athena, the goddess of wisdom and warriors in the Greek pantheon. As the patron of the arts, Minerva's domain (along with Mars included warfare, which was seen as an art-form itself.[1]

Etymology and Origins

Minerva probably originated as a local Etruscan goddess, although she was not worshiped as early as other Roman deities such as Jupiter and Juno.[2] Her name is virtually identical to that Menrva, the Etruscan goddess of the arts. The Romans may have associated her Etruscan name with their Latin word mens meaning "mind" since one of the goddess' aspects was the intellect. The name "Minerva" may also derive from the Indo-European root men, from which the English words "mental" and "mind" are also derived.

It was only when she was identified with the Greek goddess Athena that Minerva gained her role as a deity of war and combat. Like Athena, Minerva came to be represented in art bearing a weapon and amour, and shared her primary festival with Mars, another war deity. In Rome, however, she was worshiped more prominently as a goddess of all activities involving mental adeptness, such as handicrafts, writing and artistic endeavors. She was also the Roman goddess of school children.[3]

Mythology

Inheriting Greek myths concerning Athena, the Romans described Minerva as the daughter of the supreme sky god Jupiter (cognate with the high Greek god, Zeus), though she was not born in the usual way. After Jupiter made love to Wisdom (Metis in the Greek version), he immediately swallowed her, as it was prophesied that her child would be more powerful than he. Despite his efforts, Wisdom had already conceived a child. Nine months later, Jupiter found himself suffering from excruciating headaches. In order to relieve the pressure upon his ruler's temples, Vulcan, the smith god, cleaved Jupiter's head with an axe. At this point, Minerva lept out of Jupiter's skull, fully grown and dressed in full armor, including helmet, shield, and a long trailing robe, with a spear in her hand.

By the time she had reached adulthood, it was well known that Minerva was greatly skilled in the practice of weaving. She grew somewhat perturbed when she learned that a woman by the name of Arachne had proficiency with the loom which was equal to her own. This situation was exacerbated when Arachne boasted that her skills were superior to those of Minerva, and gave the wise warrior goddess no credit for her successes. Minerva disguised herself as an aged woman and warned Arachne that she was best not to challenge the gods. Arachne ignored the advice and openly challenged Minerva. At this point, Minerva threw aside her disguise and revealed her divine identity, bidding that a weaving competition should begin. Both she and Arachne wove elaborate tapestries dedicated to the myths of Rome, Minerva depicting scenes where mortals challenged the gods and Arachne depicting their more lecherous conquests. In the end, Minerva inspected Arachne's work and found it to be perfect. In a jealous rage, she tore up Arachne's tapestry, and the mortal woman hung herself in the wake of her loss. Taking a small measure of pity on the girl, Minerva transformed Arachne into a spider.

Minerva is also credited with the invention of music, which corresponded to her construction of the double flute from a stag's bones. Although the first notes she played on this instrument were delightful to the ear, Juno and Venus mocked the sound that issued forth. Afterwards, Minerva sat down beside a quiet pool of water and played her flute again. In the water before her, she saw the way in which her cheeks puffed out comically with each breath she took into the flute, and promptly threw her invention aside, placing a curse of death on whosoever should pick it up.

Worship

The Romans celebrated a festival for Minerva on the day of Quinquatria. This festival took place from March 19 to March 23, the fifth day after the Ides of March, widely accepted as a holiday for artisans. A lesser version, the Minusculae Quinquatria, was held on the Ides of June (June 13), and celebrated primarily by flute-players, who were particularly useful in the sphere of religion. In 207 B.C.E., a guild of poets and actors was formed to meet and make votive offerings at the temple of Minerva on the Aventine hill. Among others, its members included Livius Andronicus (c. 284- c. 204 B.C.E.). The Aventine sanctuary of Minerva continued to be an important center of the arts for much of the middle Roman Republic.

Worship of Minerva spread along the Roman empire, as is the case in Britain, where she was conflated with the local wisdom goddess Sulis. However, with the acknowledgment of Christianity as the state religion of Rome in the fourth century C.E., worship of the various polytheistic dieties including Minerva faded into oblivion. Interestingly enough, worship of Minerva resurfaced in the early twentieth century in Guatemala. During that time, Manuel José Estrada Cabrera, President of Guatemala, tried to promote a "Cult of Minerva" in his country. This movement left little legacy other than a few interesting Hellenic-style "temples" in parks throughout Guatemala.

Temples

Minerva was acknowledged throughout Italy, though the most prominent site dedicated to her worship was situated on the Capitoline Hill. Here, at the Temple of Minerva Medica, she was recognized as one of the Capitoline Triad along with Jupiter and Juno, the three foremost gods in the Roman pantheon. This temple was built in the republican era (510 B.C.E. - first century B.C.E.) and is often referenced in literary works of that time period, though no remains of it have been found. Since the seventeenth century, it has been wrongly identified with the ruins of the Temple of Minerva Medica nymphaeum, which is located at a nearby site, on account of the erroneous impression that the Athena Giustiniani, an Antonine Roman marble copy of a Greek sculpture of Pallas Athena, had been found among its ruins.

Minerva was also of great importance at the "Delubrum Minervae," a temple founded around 50 B.C.E. by Pompey. Few details of the ruined temple are known, though upon the site on which it was built there stands today a famous Christian church, the Santa Maria sopra Minerva. In Assisi, another church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva was built in the sixteenth century within the surviving inner chamber (or cella) of a late Republican temple of Minerva. Its Corinthian portico still stands.

Influence

Although Minerva is no longer worshiped today, she has persisted as one of the Roman deities most commonly alluded to among the cognoscenti and their folds. As patron goddess of wisdom, Minerva is frequently featured at educational establishments in the form of a statue, or as an image upon seals, among other forms. For example, a statue of Minerva is located in the center of La Sapienza University, the most important university of Rome. Minerva is considered the guardian of Guadalajara, Mexico, where she stands over a fountain, created by sculptor Pedro Medina Guzmán. Minerva is also displayed in front of Columbia University's Low Library as "Alma Mater." Minerva decorates the keystone over the main entrance to the Boston Public Library, the original publicly-financed library in America, beneath the words, "Free to all." Minerva is featured on the seals and logos of many institutions of higher learning, including the University of Lincoln in the United Kingdom, the University at Albany, NY, the University of Alabama, and Union College in New York, among others. Minerva is also featured in the logo of the world famous Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science in Germany.

The goddess Minerva is also alluded to in numerous academic publications and literary works. For instance, Minerva is a triannual magazine for members of the Royal Dublin Society. Minerva is also a section heading in the British Medical Journal, an obvious allusion to her healing powers. In a similar vein, Minerva Medica is the name of an Italian publisher of medical journals and books. The journal of the Special Air Service Regiment of the British Army is titled Mars and Minerva, taking its name from the male and female Roman war deities. In addition, countless literary and popular fictional characters have been named after Minerva, particularly those who exude great skill or genius.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Grant, Michael & John Hazel. Who's Who in Classical Mythology. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973. ISBN 0297766007

- Grimal, Pierre. A Concise Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990. ISBN 0631166963

- Lenardon, Robert J. et al. A Companion to Classical Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780195147254

- Morford, Mark P. O. & Robert J. Lenardon. Classical Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 9780195153446

- Scheid, John. An Introduction to Roman Religion. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2003. ISBN 0253216605

External Links

All links retrieved May 31, 2025.

- Temple of Minerva Assisi Guida Turistica

- Platner, Samuel Ball. Minerva Medica A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby). London: Oxford University Press, 1929.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Minerva history

- Santa_Maria_sopra_Minerva history

- Temple_of_Minerva_Medica history

- Temple_of_Minerva_Medica_(temple) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.