French Empire

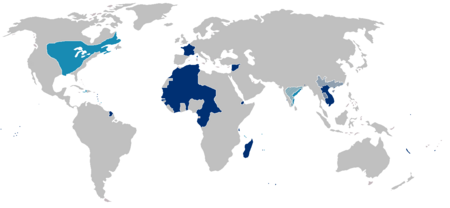

France had colonial possessions, in various forms, from the beginning of the 17th century until the 1960s. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, its global colonial empire was the second largest behind the British Empire. At its peak, between 1919 and 1939, the second French colonial empire extended over 12,347,000 km² (4,767,000 sq. miles) of land. Including metropolitan France, the total area of land under French sovereignty reached 12,898,000 km² (4,980,000 sq. miles) in the 1920s and 1930s, which is 8.6 percent of the world's land area.

Currently, the remnants of this large empire are various islands and archipelagos located in the North Atlantic, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, the South Pacific, the North Pacific, and the Antarctic Ocean, as well as one mainland territory in South America, totaling altogether 123,150 km² (47,548 sq. miles), which amounts to only 1 percent of the pre-1939 French colonial empire's area, with 2,564,000 people living in them in 2007. All of these enjoy full political representation at the national level, as well as varying degrees of legislative autonomy. In the twentieth centuries, several wars took place as colonies asserted their right to freedom most notably in what became Vietnam and in Algeria. To some extent, this subsequently made it difficult for France to be seen as the friend of freedom. On the other hand, relations between France and many former colonies, where French is still widely spoken, have been positive.

Almost all former colonies belonged to the "French Community," before this was dissolved during the war in Algeria. Traditionally, France has distanced itself from the foreign policies of some of its closest allies, such as the United States in order both to protect its own interests and to mediate from a more neutral stance. This has been especially true in relation with the Arab world, where it had League of Nations mandated territory where it has attempted to retain ties with, for example, both Syria and Lebanon despite issues about Syrian interference in Lebanese politics. France gives considerable aid to former colonies. It has military agreements with some. Debate continues in France about whether in teaching French history, so-called positive aspects of the colonial enterprise should be included, such as the building of infrastructure and the establishment of schools and health-care systems, as well as the rule of law. Others argue that most of what can be described as "positive" mainly benefited French settlers.[1] Whether colonialism can properly be described as having had positive aspects or not, it created cultural and linguistic links across the globe and helped to create consciousness that in the end all humans occupy a single planetary home, which, if not kept healthy and sustainable, will become our common grave. The French may not have actually spread Liberté, égalité, and fraternité throughout their empire but their own literature and revolutionary legacy did inspire many to aspire for freedom, self-reliance, and dignity.

Overview

French imperialism stemmed partly from rivalry and competition with her neighbors, initially Spain and Portugal and later with the British Empire and partly from commercial and economic interests. The main period of French colonial expansion took place after the establishment of the Third Republic in 1870. Napoleon III's war with Prussia burdened France with reparations that had to be paid. In addition, however, the French saw themselves as promoting the values of the Enlightenment and as extending and glorifying French culture, even as recreating the Roman imperial space that had existed on both sides of the Mediterranean.[2] Given France's republican identity at this time, the idea of promoting democracyâeven though democratization was very limited in the colonial spaceâwas also a factor in France's imperial project. Algeria, which from as early as 1848 was a department of France and so officially no longer a colony, was regarded as an extension of France into Africa, which, in the tradition of the Roman Empire, was not really seen as radically different from the European space. To some extent, this was true of the whole of French Africa, which stretched, in a contiguous line, from the North to the Gold Coast except (until 1914) for German Cameroon. The process of Frenchification was meant to bind people across ethnic and racial differences into a single Francophone and Francophile community. To some degree, racism based on skin-color was not as rampant within the French as within other imperial spaces. In the French space, adoption of French culture overrode ethnicity.

First French colonial empire

The early voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano and Jacques Cartier in the early sixteenth century, as well as the frequent voyages of French fishermen to the Grand Banks off Newfoundland throughout that century, were the precursors to the story of France's colonial expansion. But Spain's jealous protection of its American monopoly, and the disruptions caused in France itself by the Wars of Religion in the later sixteenth century, prevented any consistent efforts by France to establish colonies. Early French attempts to found colonies in Brazil, in 1555, at Rio de Janeiro ("France Antarctique") and in 1612, at São LuÃs ("France Ãquinoxiale"), and in Florida (including Fort Caroline in 1562) were not successful, due to Portuguese and Spanish vigilance.

The story of France's colonial empire truly began on July 27, 1605, with the foundation of Port Royal in the colony of Acadia in North America, in what is now Nova Scotia, Canada. A few years later, in 1608, Samuel De Champlain founded Quebec, which was to become the capital of the enormous, but sparsely settled, fur-trading colony of New France (also called Canada).

Although, through alliances with various Native American tribes, the French were able to exert a loose control over much of the North American continent, areas of French settlement were generally limited to the St. Lawrence River Valley. Prior to the establishment of the 1663 Sovereign Council, the territories of New France were developed as mercantile colonies. It is only after the arrival of intendant Jean Talon, in 1665, that France gave its American colonies the proper means to develop population colonies comparable to that of the British. But there was relatively little interest in colonialism in France, which concentrated rather on dominance within Europe, and for most of the history of New France, even Canada was far behind the British North American colonies in both population and economic development. Acadia itself was lost to the British in the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.

In 1699, French territorial claims in North America expanded still further, with the foundation of Louisiana in the basin of the Mississippi River. The extensive trading network throughout the region connected to Canada through the Great Lakes, was maintained through a vast system of fortifications, many of them centered in the Illinois Country and in present-day Arkansas.

As the French empire in North America grew, the French also began to build a smaller but more profitable empire in the West Indies. Settlement along the South American coast in what is today French Guiana began in 1624, and a colony was founded on Saint Kitts in 1625 (the island had to be shared with the English until the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, when it was ceded outright). The Compagnie des Ãles de l'Amérique founded colonies in Guadeloupe and Martinique in 1635, and a colony was later founded on Saint Lucia by (1650).

The food-producing plantations of these colonies were built and sustained through slavery, with the supply of slaves dependent on the African slave trade. Local resistance by the indigenous peoples resulted in the Carib Expulsion of 1660.

The most important Caribbean colonial possession did not come until 1664, when the colony of Saint-Domingue (today's Haiti) was founded on the western half of the Spanish island of Hispaniola. In the eighteenth century, Saint-Domingue grew to be the richest sugar colony in the Caribbean. The eastern half of Hispaniola (today's Dominican Republic) also came under French rule for a short period, after being given to France by Spain in 1795.

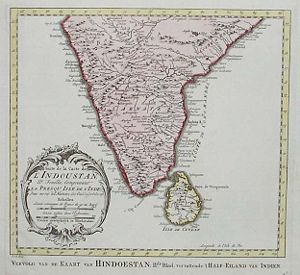

French colonial expansion was not limited to the New World, however. In Senegal in West Africa, the French began to establish trading posts along the coast in 1624. In 1664, the French East India Company was established to compete for trade in the east. Colonies were established in India in Chandernagore (1673) and Pondicherry in the Southeast (1674), and later at Yanam (1723), Mahe (1725), and Karikal (1739). Colonies were also founded in the Indian Ocean, on the Ãle de Bourbon (Réunion, 1664), Ãle de France (Mauritius, 1718), and the Seychelles (1756).

Colonial conflict with Britain

In the mid-eighteenth century, a series of colonial conflicts began between France and Britain, which would ultimately result in the demise of most of the first French colonial empire. These wars were the War of the Austrian Succession (1744â1748), the Seven Years' War (1756â1763), the War of the American Revolution (1778â1783), and the French Revolution (1793â1802) and Napoleonic (1803-1815) Wars. It may even be seen further back in time to the first of the French and Indian Wars. This recurrent conflict is known as the so-called Second Hundred Years' War.

Although the War of the Austrian Succession was indecisiveâdespite French successes in India under the French Governor-General Joseph François Dupleix â the Seven Years' War, after early French successes in Minorca and North America, saw a French defeat, with the numerically superior British (over one million to about 50 thousand French settlers) conquering not only New France (excluding the small islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon), but also most of France's West Indian (Caribbean) colonies, and all of the French Indian outposts. While the peace treaty saw France's Indian outposts, and the Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe restored to France, the competition for influence in India had been won by the British, and North America was entirely lostâmost of New France was taken by Britain (also referred to as British North America, except Louisiana, which France ceded to Spain as payment for Spain's late entrance into the war (and as compensation for Britain's annexation of Spanish Florida). Also ceded to the British were Grenada and Saint Lucia in the West Indies. Although the loss of Canada would cause much regret in future generations, it excited little unhappiness at the time; colonialism was widely regarded as both unimportant to France, and immoral.

Some recovery of the French colonial empire was made during the French intervention in the American Revolution, with Saint Lucia being returned to France by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, but not nearly as much as had been hoped for at the time of French intervention. True disaster came to what remained of France's colonial empire in 1791 when Saint Domingue (comprised of the Western third of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola), France's richest and most important colony, was riven by a massive slave revolt, caused partly by the divisions among the island's elite, which had resulted from the French Revolution of 1789. The slaves, led eventually by Toussaint Louverture and then, following his capture by the French in 1801, by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, held their own against French, Spanish, and British opponents, and ultimately achieved independence as Haiti in 1804 (Haiti became the first black republic in the world, much earlier than any of the future African nations). In the meanwhile, the newly resumed war with Britain by the French, resulted in the British capture of practically all remaining French colonies. These were restored at the Peace of Amiens in 1802, but when war resumed in 1803, the British soon recaptured them. France's repurchase of Louisiana in 1800 came to nothing, as the final success of the Haitian revolt convinced Bonaparte that holding Louisiana would not be worth the cost, leading to its sale to the United States in 1803 (the Louisiana Purchase). Nor was the French attempt to establish a colony in Egypt in 1798â1801 successful. On the other hand, enduring cultural links were established between France and Egypt which greatly impacted on the development of Arab nationalism. Egypt also adopted the Napoleonic Code.

Second French colonial empire

At the close of the Napoleonic Wars, most of France's colonies were restored to it by Britain, notably Guadeloupe and Martinique in the West Indies, French Guiana on the coast of South America, various trading posts in Senegal, the Ãle Bourbon (Réunion) in the Indian Ocean, and France's tiny Indian possessions. Britain finally annexed Saint Lucia, Tobago, the Seychelles, and the Ãle de France (Mauritius), however.

The true beginnings of the second French colonial empire, however, were laid in 1830, with the French invasion of Algeria, which was conquered over the next 17 years. During the Second Empire, headed by Napoleon III, an attempt was made to establish a colonial-type protectorate in Mexico, but this came too little, and the French were forced to abandon the experiment after the end of the American Civil War, when the American president, Andrew Johnson, invoked the Monroe Doctrine. This French intervention in Mexico lasted from 1861 to 1867. Napoleon III also established French control over Cochinchina (the southernmost part of modern Vietnam including Saigon) in 1867 and 1874, as well as a protectorate over Cambodia in 1863.

It was only after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870â1871 and the founding of the Third Republic (1871-1940) that most of France's later colonial possessions were acquired. From their base in Cochinchina, the French took over Tonkin (in modern northern Vietnam) and Annam (in modern central Vietnam) in 1884-1885. These, together with Cambodia and Cochinchina, formed French Indochina in 1887 (to which Laos was added in 1893, and Kwang-Chou-Wan in 1900). In 1849, the French concession in Shanghai was established, lasting until 1946.

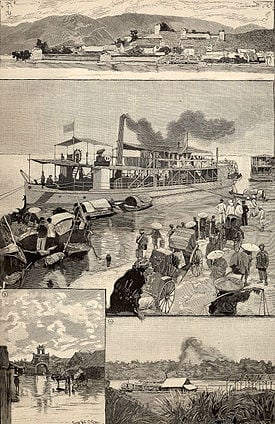

1. Panorama of Lac-Kaï, French outpost in China.

2. Yun-nan, in the quay of Hanoi.

3. Flooded street of Hanoi.

4. Landing stage of Hanoi

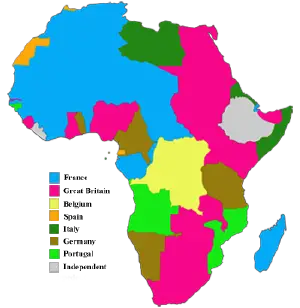

Influence was also expanded in North Africa, establishing a protectorate on Tunisia in 1881 (Bardo Treaty). It was this that launched the Scramble for Africa, where the largest slice of territory was under French rule, with Britain in second place. Gradually, French control was established over much of Northern, Western, and Central Africa by the turn of the century (including the modern nations of Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea, Mali, Côte d'Ivoire, Benin, Niger, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo), as well as the east African coastal enclave of Djibouti (French Somaliland). The Voulet-Chanoine Mission, a military expedition, was sent out from Senegal in 1898, to conquer the Chad Basin and unify all French territories in West Africa. This expedition operated jointly with two other expeditions, the Foureau-Lamy and Gentil missions, which advanced from Algeria and Middle Congo respectively. With the death of the Muslim warlord Rabih az-Zubayr, the greatest ruler in the region, and the creation of the Military Territory of Chad in 1900, the Voulet-Chanoine Mission had accomplished all its goals. The ruthlessness of the mission provoked a scandal in Paris. As a part of the Scramble for Africa, France had the establishment of a continuous west-east axis of the continent as an objective, in contrast with the British north-south axis. This resulted in the Fashoda incident, were an expedition led by Jean-Baptiste Marchand was opposed by forces under Lord Kitchener's command. The resolution of the crisis had a part in the bringing forth of the Entente Cordiale. During the Agadir Crisis in 1911, Britain supported France and Morocco became a French protectorate.

At this time, the French also established colonies in the South Pacific, including New Caledonia, the various island groups which make up French Polynesia (including the Society Islands, the Marquesas, the Tuamotus), and established joint control of the New Hebrides with Britain.

The French made their last major colonial gains after the First World War, when they gained mandates over the former Turkish territories of the Ottoman Empire that make up what is now Syria and Lebanon, as well as most of the former German colonies of Togo and Cameroon. A hallmark of the French colonial project in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century was the civilizing mission (mission civilisatrice), the principle that it was Europe's duty to bring civilization to benighted peoples. As such, colonial officials undertook a policy of Franco-Europeanization in French colonies, most notably French West Africa. Africans who adopted French culture, including fluent use of the French language and conversion to Christianity, were granted equal French citizenship, including suffrage. Later, residents of the "Four Communes" in Senegal were granted citizenship in a program led by the Afro-French politician Blaise Diagne.

Collapse of the empire

The French colonial empire began to fall apart during the Second World War, when various parts of their empire were occupied by foreign powers (Japan in Indochina, Britain in Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, the U.S. and Britain in Morocco and Algeria, and Germany in Tunisia). However, control was gradually reestablished by Charles de Gaulle. The French Union, included in the 1946 Constitution, replaced the former colonial Empire.

However, France was immediately confronted with the beginnings of the decolonization movement. Paul Ramadier (SFIO)'s cabinet repressed the Malagasy insurrection in 1947. In Asia, Ho Chi Minh's Vietminh declared Vietnam's independence, starting the Franco-Vietnamese War. In Cameroun, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon's insurrection, started in 1955, and headed by Ruben Um Nyobé, was violently repressed.

When this ended with French defeat and withdrawal from Vietnam in 1954, the French almost immediately became involved in a new, and even harsher conflict in their oldest major colony, Algeria. Ferhat Abbas and Messali Hadj's movements had marked the period between the two wars, but both sides radicalized after the Second World War. In 1945, the Sétif massacre was carried on by the French army. The Algerian War started in 1954. Algeria was particularly problematic for the French, due to the large number of European settlers (or pieds-noirs) who had settled there in the 125 years of French rule. The conviction that Algeria was part of France was so strong that when the French colons left Algeria in 1962, "they saw themselves as political refugees fleeing from their own land, not as victims of decolonization."[3] Charles de Gaulle's accession to power in 1958, in the middle of the crisis ultimately led to independence for Algeria with the 1962 Evian Accords.

Legacy

Former colonies became part of the French Union, which was replaced in the new 1958 Constitution by the French Community. Only Guinea refused by referendum to take part to the new colonial organization. However, the French Community dissolved itself in the midst of the Algerian War; all of the other African colonies were granted independence in 1960, following local referendums. Some few colonies chose instead to remain part of France, under the statuses of overseas départements (territories). Critics of neocolonialism claimed that the Françafrique had replaced formal direct rule. They argued that while de Gaulle was granting independence on one hand, he was creating new ties through Jacques Foccart's help, his counselor for African matters. Foccart supported in particular the Biafra secession (or Nigerian civil war) during the late 1960s.

The legacy of empire to some degree enables France to pursue an independent foreign policy and to argue for continued permanent member status of the United National Security Council. The French empire has ensured that the French language remains one of the most widely spoken and that many former colonies maintain strong educational and cultural ties with France. French is an official language in 28 countries (including other European countries, Belgium, Luxembourg and Switzerland which were not part of the French empire). Some 10 percent of the population of France settled there from or are descended from people who settled there from former colonies. Race relations, immigration, and debate about assimilation are hotly debated in French politics but traditionally a willingness to adopt French culture has tended to minimize difference based on skin-color or ethnicity. What the French find problematic are practices that appear to be counter-cultural, such as the public display of religious identity in what has been a predominantly secular state since the French Revolution. This resulted in the controversial ban on wearing religious symbols which has impacted most visibly on Muslim women who choose to wear a head-scarf. The law concerns the application of the principle of secularism and has been effective since March 2004.

Notes

- â Samah Jabr, Colonialismâs Residual Legacy: The French Example, Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- â Jim Jones, The French in West Africa: French Motivations for Imperialism (West Chester, PA: West Chester University of Pennsylvania). Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- â Clinton Bennett, Muslim and Modernity (London: Continuum. ISBN 0826454828).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boucher, Philip P. The Shaping of the French Colonial Empire: A Bio-bibliography of the Careers of Richelieu, Fouquet, and Colbert. New York: Garland Pub., 1985. ISBN 978-1138549500

- Chafer, Tony, and Amanda Sackur. French Colonial Empire and the Popular Front: Hope and Disillusion. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0333729731

- Cohen, William B.Rulers of Empire: The French Colonial Service in Africa. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1971. ISBN 978-0817919511.

- Pakenham, Thomas. The Scramble for Africa. New York: Random House/Abacus, 1991. ISBN 0349104492.

- Petringa, Maria Brazza. A Life for Africa. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2006. ISBN 978-1425911980.

- Singer, Barnett, and John W. Langdon. Cultured Force: Makers and Defenders of the French Colonial Empire. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0299199005.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.