Difference between revisions of "Moon" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 232: | Line 232: | ||

===Atmosphere=== | ===Atmosphere=== | ||

The Moon has a relatively insignificant and tenuous atmosphere. One source of this atmosphere is [[outgassing]] - the release of gases, for instance [[radon]], which originate deep within the Moon's interior. Another important source of gases is the [[solar wind]], which is briefly captured by the Moon's gravity. | The Moon has a relatively insignificant and tenuous atmosphere. One source of this atmosphere is [[outgassing]] - the release of gases, for instance [[radon]], which originate deep within the Moon's interior. Another important source of gases is the [[solar wind]], which is briefly captured by the Moon's gravity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Space weathering=== | ||

| + | Lunar samples returned by [[Apollo]] and [[Luna]] missions gave us the first evidence of [[space weathering]], which is a common phenomenon occurring on most airless bodies in our solar system. Space weathering makes the planetary surface darker and optically redder, making the remote compositional analysis difficult. Recent studies and exploration to the S-type [[asteroid]]s have been also revealing the mechanism of space weathering. | ||

==Astronomical effects== | ==Astronomical effects== | ||

Revision as of 10:49, 16 August 2006

|

The Moon as seen from Earth | |||||||

| Orbital characteristics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orbital circumference | 2,413,402 km (0.016 AU) | ||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0554 | ||||||

| Perigee | 363,104 km (0.0024 AU) | ||||||

| Apogee | 405,696 km (0.0027 AU) | ||||||

| Revolution period

(Sidereal period) |

27.321 66155 d (27 d 7 h 43.2 min) | ||||||

| Synodic period | 29.530 588 d (29 d 12 h 44.0 min) | ||||||

| Avg. Orbital Speed | 1.022 km/s | ||||||

| Max. Orbital Speed | 1.082 km/s | ||||||

| Min. Orbital Speed | 0.968 km/s | ||||||

| Inclination | varies between 28.60° and 18.30° (5.145 396° to ecliptic) | ||||||

| Longitude of the ascending node |

Regressing, 1 revolution in 18.6 years | ||||||

| Argument of perigee | Progressing, 1 revolution in 8.85 years | ||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||

| Equatorial diameter | 3,476.2 km[1] (0.273 Earths) | ||||||

| Polar diameter | 3,472.0 km (0.273 Earths) | ||||||

| Oblateness | 0.0012[2] | ||||||

| Surface area | 3.793×107 km2 (0.074 Earths) | ||||||

| Volume | 2.1958×1010 km3 (0.020 Earths) | ||||||

| Mass | 7.347 673×1022 kg (0.0123 Earths) | ||||||

| Mean density | 3,346.2 kg·m−3 | ||||||

| Equatorial gravity | 1.622 m·s−2 (0.1654 gee) | ||||||

| Escape velocity | 2.38 km·s−1 | ||||||

| Rotation period | 27.321 661 d (synchronous) | ||||||

| Rotation velocity | 16.655 km·h−1 (at the equator) | ||||||

| Axial tilt | 1.5424° to ecliptic | ||||||

| Albedo | 0.12 | ||||||

| Magnitude | -12.74 | ||||||

| Surface temperature |

| ||||||

| Bulk composition of the Moon's

mantle and crust (weight %, estimated) | |||||||

| Oxygen | 42.6 % | ||||||

| Magnesium | 20.8 % | ||||||

| Silicon | 20.5 % | ||||||

| Iron | 9.9 % | ||||||

| Calcium | 2.31 % | ||||||

| Aluminium | 2.04 % | ||||||

| Nickel | 0.472 % | ||||||

| Chromium | 0.314 % | ||||||

| Manganese | 0.131 % | ||||||

| Titanium | 0.122 % | ||||||

| Atmospheric characteristics | |||||||

| Atmospheric pressure | 3 × 10-13 kPa | ||||||

| Helium | 25 % | ||||||

| Neon | 25 % | ||||||

| Hydrogen | 23 % | ||||||

| Argon | 20 % | ||||||

| Methane, Ammonia |

trace | ||||||

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. Natural satellites of other planets are also called moons, although they usually have their own unique names (e.g., Phobos and Deimos which are satellites of Mars). The Moon's symbol is a crescent. The terms lunar, selene/seleno-, and -cynthion (from the Lunar deities Selene and Cynthia) refer to the Moon (aposelene, selenocentric, pericynthion, etc.).

The average distance from the Moon to the Earth is 384,403 kilometers (238,857 miles). The Moon's diameter is 3,476 kilometres (2,160 miles). Reflected sunlight from the Moon's surface reaches Earth in 1.3 seconds (at the speed of light).

The first man-made object to land on the Moon was Luna 2 in 1959, the first photographs of the otherwise occluded far side of the Moon were made by Luna 3 in the same year, and the first people to land on the Moon came aboard Apollo 11 in 1969.

The two sides of the Moon

The Moon is in synchronous rotation, meaning that it keeps nearly the same face turned toward Earth at all times (there is a small variation, called libration). The side of the Moon that faces Earth is called the near side, and the opposite side is called the far side. The far side is also sometimes called the "dark side", which means "unknown and hidden", and not "lacking light" as might seem to be implied by the name; in fact, the far side receives (on average) as much sunlight as the near side, but at opposite times. Spacecraft are cut off from direct radio communication with Earth when on the far side of the Moon due to line of sight. One distinguishing feature of the far side is its almost complete lack of maria (singular: mare), which are the dark albedo features.

| 90° W | Near side | 90° E | Far side | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Orbit and relationship to Earth

Orbit

Several ways to consider a complete orbit are detailed in the table below, but the two most familiar are: the sidereal month being the time it takes to make a complete orbit with respect to the stars, about 27.3 days; and the synodic month being the time it takes to reach the same phase, about 29.5 days. These differ because in the meantime the Earth and Moon have both orbited some distance around the Sun.

Tides on Earth

The gravitational attraction that the Moon exerts on Earth is the cause of tides in the sea. The tidal flow period, but not the phase, is synchronized to the Moon's orbit around Earth. The tidal bulges on Earth, caused by the Moon's gravity, are carried ahead of the apparent position of the Moon by the Earth's rotation, in part because of the friction of the water as it slides over the ocean bottom and into or out of bays and estuaries. As a result, some of the Earth's rotational momentum is gradually being transferred to the Moon's orbital momentum, resulting in the Moon slowly receding from Earth at the rate of approximately 38 millimetres per year. At the same time the Earth's rotation is gradually slowing, the Earth's day thus lengthens by about 15 µs every year.

Synchronous rotation

The Moon is in synchronous rotation, meaning that it keeps the same face turned to the Earth at all times. This synchronous rotation is only true on average because the Moon's orbit has definite eccentricity. When the Moon is at its perigee, its rotation is slower than its orbital motion, and this allows us to see up to an extra eight degrees of longitude of its East (right) side. Conversely, when the Moon reaches its apogee, its rotation is faster than its orbital motion and reveals another eight degrees of longitude of its West (left) side. This is called longitudinal libration.

Origin and history

Recently, the giant impact hypothesis has been considered the most plausible scientific hypothesis for the Moon's origin than other hypotheses such as coformation and condensation. The Giant Impact hypothesis holds that the Moon formed from the ejecta resulting from a collision between a very early, semi-molten Earth and a planet-like object the size of Mars. The material ejected from this impact would have gathered in orbit around Earth and formed the Moon. This hypothesis is bolstered by two main observations: First, the composition of the Moon resembles that of Earth's crust, whereas it has relatively few heavy elements that would have been present if it formed by itself out of the same material from which Earth formed. Second, through radiometric dating, it has been determined that the Moon's crust formed between 20 and 30 million years after that of Earth, despite its smallness and associated larger loss of internal heat, although it has been suggested that this hypothesis does not adequately address the abundance of volatile elements in the moon.[3] In addition, the fact that the Moon and the Earth have the same oxygen isotopic abundance trend confirmed with Apollo 11 samples supports this hypothesis.

At that time the Moon was much closer to the Earth and strong tidal forces deformed the once molten sphere into an ellipsoid, with the major axis pointed towards Earth. When the Moon started to cool, a solid crust was formed along its surface, but its molten interior remained displaced in the direction of the Earth. Said otherwise: the crust on the near side was much thinner than on the far side. Especially during the late heavy bombardment, around 3.8 to 4 billion years ago, many large meteorites were able to penetrate the thin crust of the near side but only very few could do so on the far side. Where the crust was perforated the hot lavas from the interior oozed out and spread over the surface, only to cool down later into the maria as we know them nowadays. This explains the paucity of maria on the far side.

The geological epochs of the Moon are defined based on the dating of various significant impact events in the Moon's history. The period of the late heavy bombardment is determined by analysis of craters and Moon rocks. In 2005, a team of scientists from Germany, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland measured the Moon's age at 4527 ± 10 million years, which would imply that it was formed only 30 to 50 million years after the origin of the solar system.[4]

Physical characteristics

Composition

More than 4.5 billion years ago, the surface of the Moon was a liquid magma ocean. Scientists think that one component of lunar rocks, called KREEP (potassium (K), rare earth elements (REE), and phosphorus (P)), represents the last chemical remnant of that magma ocean. KREEP is actually a composite of what scientists term "incompatible elements": those that cannot fit into a crystal structure and thus were left behind, floating to the surface of the magma. For researchers, KREEP is a convenient tracer, useful for reporting the story of the volcanic history of the lunar crust and chronicling the frequency of impacts by comets and other celestial bodies.

The lunar crust is composed of a variety of primary elements, including uranium, thorium, potassium, oxygen, silicon, magnesium, iron, titanium, calcium, aluminium, and hydrogen, as determined by spectroscopy.

A complete global mapping of the Moon for the abundance of these elements has never been performed. However, some spacecraft have done so for some of the elements over portions of the Moon; Galileo, Clementine, and Lunar Prospector to name a few. The overall composition of the Moon is believed to be similar to that of the upper parts of the Earth other than a depletion of volatile elements and of iron.

Selenography

When observed with earth-based telescopes, the Moon can be seen to have some 30,000 craters having a diameter of at least 1 km, but close up observation from lunar orbit reveals a multitude of ever smaller craters. Most are hundreds of millions or billions of years old; the lack of atmosphere, weather and recent geological processes ensures that most of them remain permanently preserved. There are place on the Moon where it is impossible to add a crater of any size without obliterating another; this is termed saturation.

The largest crater on the Moon, and indeed the largest known crater within the solar system, forms the South Pole-Aitken basin. This crater is located on the far side, near the South Pole, and is some 2,240 kilometres in diameter and 13 kilometres in depth.

The dark and relatively featureless lunar plains are called maria, Latin for seas, since they were believed by ancient astronomers to be water-filled seas. They are actually vast ancient basaltic lava flows that filled the basins of large impact craters. The lighter-colored highlands are called terrae. Maria are found almost exclusively on the Lunar nearside, with the Lunar far side having only a few scattered patches.

Blanketed atop the Moon's crust is a dusty outer rock layer called regolith, the result of rocks shattered by billions of years of impacts. Both the crust and regolith are unevenly distributed over the entire Moon. The crust ranges from 60 kilometres (38 mi) on the near side to 100 kilometres (63 mi) on the far side. The regolith varies from 3 to 5 metres (10 to 16 ft) in the maria to 10 to 20 metres (33 to 66 ft) in the highlands.

In 2004, a team led by Dr. Ben Bussey of Johns Hopkins University using images taken by the Clementine mission determined that four mountainous regions on the rim of the 73-km-wide Peary crater at the Moon's north pole appeared to remain illuminated for the entire Lunar day. These unnamed "mountains of eternal light" are possible due to the Moon's extremely small axial tilt, which also gives rise to permanent shadow at the bottoms of many polar craters. No similar regions of eternal light exist at the less mountainous south pole, although the rim of Shackleton crater is illuminated for 80% of the lunar day. Clementine's images were taken during the northern Lunar hemisphere's summer season, and it remains unknown whether these four mountains are shaded at any point during their local winter season.

Dating of the lunar impact events through 40Ar/39Ar isotope analysis of glass spherules, created during the impacts, showed a high impact number in early lunar history and in the last 400 million years.[5] [6]

Presence of water

Over time, comets and meteoroids continuously bombard the Moon. Many of these objects are water-rich. Energy from sunlight splits much of this water into its constituent elements hydrogen and oxygen, both of which usually fly off into space immediately. However, it has been hypothesized that significant traces of water remain on the Moon, either on the surface, or embedded within the crust. The results of the Clementine mission suggested that small, frozen pockets of water ice (remnants of water-rich comet impacts) may be embedded unmelted in the permanently shadowed regions of the lunar crust. Although the pockets are thought to be small, the overall amount of water was suggested to be quite significant — 1 km³.

Some water molecules, however, may have literally hopped along the surface and become trapped inside craters at the lunar poles. Due to the very slight "tilt" of the Moon's axis, only 1.5°, some of these deep craters never receive any light from the Sun — they are permanently shadowed. Clementine has mapped[7] craters at the lunar south pole[8] which are shadowed in this way. It is in such craters that scientists expect to find frozen water if it is there at all. If found, water ice could be mined and then split into hydrogen and oxygen by solar panel-equipped electric power stations or a nuclear generator. The presence of usable quantities of water on the Moon would be an important factor in rendering lunar habitation cost-effective, since transporting water (or hydrogen and oxygen) from Earth would be prohibitively expensive.

The equatorial Moon rock collected by Apollo astronauts contained no traces of water. Neither the Lunar Prospector[9] nor more recent surveys, such as those of the Smithsonian Institution, have found direct evidence of lunar water, ice, or water vapor. Lunar Prospector results, however, indicate the presence of hydrogen in the permanently shadowed regions, which could be in the form of water ice.

Magnetic field

Compared to that of Earth, the Moon has a very weak magnetic field. While some of the Moon's magnetism is thought to be intrinsic (such as a strip of the lunar crust called the Rima Sirsalis), collision with other celestial bodies might have imparted some of the Moon's magnetic properties. Indeed, a long-standing question in planetary science is whether an airless solar system body, such as the Moon, can obtain magnetism from impact processes such as comets and asteroids. Magnetic measurements can also supply information about the size and electrical conductivity of the lunar core - evidence that will help scientists better understand the Moon's origins. For instance, if the core contains more magnetic elements (such as iron) than Earth, then the impact theory loses some credibility (although there are alternate explanations for why the lunar core might contain less iron).

Atmosphere

The Moon has a relatively insignificant and tenuous atmosphere. One source of this atmosphere is outgassing - the release of gases, for instance radon, which originate deep within the Moon's interior. Another important source of gases is the solar wind, which is briefly captured by the Moon's gravity.

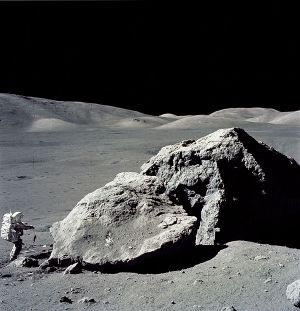

Space weathering

Lunar samples returned by Apollo and Luna missions gave us the first evidence of space weathering, which is a common phenomenon occurring on most airless bodies in our solar system. Space weathering makes the planetary surface darker and optically redder, making the remote compositional analysis difficult. Recent studies and exploration to the S-type asteroids have been also revealing the mechanism of space weathering.

Astronomical effects

Eclipses

Eclipses happen only if Sun, Earth, and Moon are lined up. Solar eclipses can only occur near a new moon; lunar eclipses can only occur near a full moon.

The angular diameters of the Moon and the Sun as seen from Earth overlap in their variation, so that both total and annular solar eclipses are possible. In a total eclipse, the Moon completely covers the disc of the Sun and the solar corona becomes visible to the naked eye.

Since the distance between the Moon and the Earth is very slightly increasing over time, the angular diameter of the Moon is decreasing. This means that hundreds of millions of years ago the Moon could always completely cover the Sun on solar eclipses so that no annular eclipses were possible. Likewise, about 600 million years from now, the Moon will no longer cover the Sun completely and no total eclipses will occur any more.

Solar eclipse was used for measuring the deviation of light from a star when the light passes very close to the Sun to check the validity of Albert Einstein's General Relativity.

Occultation of stars

The Moon is continuously blocking our view of the sky directly behind it. The Moon blocks about 1/2 degree wide circular area. When a bright star or planet passes behind the Moon it is occulted or hidden from view. A solar eclipse is an occultation of the Sun. Because the Moon is close to Earth, occultations of stars are not visible everywhere. Because of the moving nodes of the lunar orbit, each year different stars are occulted.

Appearance of the Moon

During the brightest full moons, the Moon can have an apparent magnitude of about −12.6. For comparison, the Sun has an apparent magnitude of −26.8. When the Moon is in a quarter phase, its brightness is not one half of a full Moon. It is only about 1/10 of that, because the amount of solar radiation reflected towards the Earth is highly reduced by the shadows projected by the higher parts of the Moon over the lower ones.

The Moon appears larger when close to the horizon. This is a purely psychological effect (see Moon illusion). The angular diameter of the Moon from Earth is about one half of one degree, and is actually about 1.5% smaller when the Moon is near the horizon than when it is high in the sky (because it is further away by up to 1 Earth radius).

Another quirk of the visual system causes us to see the Moon as almost pure white, when in fact it reflects only about 7% of the light falling on it (about as dark as a lump of coal). It has a very low albedo. Color constancy in the visual system recalibrates the relations between colors of an object and its surroundings; however, there is nothing next to the Moon to reflect the light falling on the Moon, therefore it is perceived as the brightest object visible. We have no standard to compare it to. An example of this is that, if you used a torch to illuminate a lump of coal in a dark room, it would look white. If you then broadened the beam of the torch to illuminate the surroundings, it would revert to black.

Various lighter and darker colored areas (primarily maria) create the patterns seen by different cultures as the Man in the Moon, the rabbit and the buffalo, amongst others. Craters and mountain chains are also prominent lunar features.

From any location on Earth, the highest altitude of the Moon on a day varies between the same limits as the Sun, and depends on season and lunar phase. For example, in winter the Moon is highest in the sky when it is full, and the full moon is highest in winter. The orientation of the Moon's crescent side also depends on the latitude of the observing site. Close to the equator an observer can see a boat Moon.[10]

We can use the Moon to visualize Earth's trajectory: When the Moon is its third quarter, it is moving in its orbit in front of the Earth. As the distance from the Earth to the Moon is about 384,404 km and the Earth's orbital speed is about 107,000 km/h, the Moon is at a point where the Earth will be about three and a half hours later. And when the Moon is in its first quarter, it is "where we were" about three and a half hours ago.

Like the Sun, the Moon can also give rise to the atmospheric effects including a 22 degree halo ring and the smaller coronal rings seen more often through thin clouds.

Exploration of the Moon

The first leap in lunar observation was caused by the invention of the telescope. Galileo Galilei made especially good use of this new instrument and observed mountains and craters on the Moon's surface.

The Cold War-inspired space race between the Soviet Union and the United States of America led to an acceleration. What was the next big step depends on the political viewpoint: In the US (and the West in general) the landing of the first humans on the Moon in 1969 is seen as the culmination of the space race. The first man to walk on the lunar surface was Neil Armstrong, commander of the American mission Apollo 11, first setting foot on the Moon at 02:56 UTC on July 21, 1969. The last man (as of 2006) to stand on the Moon was Eugene Cernan, who as part of the mission Apollo 17 walked on the Moon in December 1972. On the other hand, many scientifically important steps, such as the first photographs of the far side of the Moon in 1959, were first achieved by the Soviet Union. Lunar samples have been brought back to Earth by three Luna missions (Luna 16, 20, and 24) and the Apollo missions 11 through 17 (excepting Apollo 13, which aborted its planned lunar landing).

Multiple scientific instruments were installed during the Apollo missions; some of them still function today. Among those were seismic detectors and reflecting prisms for laser ranging.

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, there were 65 Moon landings (with 10 in 1971 alone), but after Luna 24 in 1976 they stopped. The Soviet Union started focusing on Venus and space stations and the US on Mars and beyond. In 1990 Japan visited the Moon with the Hiten spacecraft, becoming the third country to orbit the Moon. The spacecraft released the Hagormo probe into lunar orbit, but the transmitter failed rendering the mission scientifically useless.

In 1994, the U.S. finally returned to the Moon, robotically at least, sending Clementine, a Joint Defense Department/NASA mission which completed the first global multispectral data set for the Moon. This was followed by the Lunar Prospector mission in 1998, the third mission in the Discovery Program. The neutron spectrometer on Lunar Prospector confirmed the presence of excess hydrogen at the lunar poles, which some have speculated to be due to the presence of water.

On January 14 2004, US President George W. Bush called for a plan to return manned missions to the Moon by 2020. The European Space Agency has plans to launch probes to explore the Moon in the near future, too. European spacecraft Smart 1 was launched September 27, 2003 and entered lunar orbit on November 15 2004. The People's Republic of China has expressed ambitious plans for exploring the Moon and has started the Chang'e program for lunar exploration. Japan is launching the Selene mission in 2007, and a manned lunar base is planned by the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA). India is to launch an unmanned mission Chandrayaan-1 in 2008, carrying a notable US instrument, Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3).

Human understanding of the Moon

The Moon has been the subject of many works of art and literature and the inspiration for countless others. It is a motif in the visual arts, the performing arts, poetry, prose and music. A 5,000 year old rock carving at Knowth, Ireland may represent the Moon, which would be the earliest depiction discovered.

In many prehistoric and ancient cultures, the Moon was thought to be a deity or other supernatural phenomenon, and astrological views of the Moon continue to be propagated today. Among the first in the Western world to offer a scientific explanation for the Moon was the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras, who reasoned that the Sun and Moon were both giant spherical rocks, and that the latter reflected the light of the former. His atheistic view of the heavens was one cause for his imprisonment and eventual exile.

By the Middle Ages, before the invention of the telescope, more and more people began to recognize the Moon as a sphere, though they believed that it was "perfectly smooth". In 1609, Galileo Galilei drew one of the first telescopic drawings of the Moon in his book Sidereus Nuncius and noted that it was not smooth but had craters. Later in the 17th century, Giovanni Battista Riccioli and Francesco Maria Grimaldi drew a map of the Moon and gave many craters the names they still have today.

On maps, the dark parts of the Moon's surface were called maria (singular mare) or "seas", and the light parts were called terrae or continents. The possibility that the Moon could contain vegetation and be inhabited by "selenites" was seriously considered by some major astronomers even into the first decades of the 19th century.

In 1835, the Great Moon Hoax fooled some people into thinking that there were exotic animals living on the Moon. Almost at the same time however (during 1834-1836), Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich Mädler were publishing their four-volume Mappa Selenographica and the book Der Mond in 1837, which firmly established the conclusion that the Moon has no bodies of water nor any appreciable atmosphere.

There remained some controversy over whether features on the Moon could undergo changes. Some observers claimed that some small craters had appeared or disappeared, but in the 20th century it was determined that these claims were illusory, due to observing under different lighting conditions or due to the inadequacy of earlier drawings. It is however known that the phenomenon of outgassing occasionally occurs.

The far side of the Moon remained completely unknown until the Luna 3 probe was launched in 1959, and was extensively mapped by the Lunar Orbiter program in the 1960s.

From the 1950s through the 1990s, NASA aerodynamicist Dean Chapman and others advanced the "lunar origin" theory of tektites. Chapman used complex orbital computer models and extensive wind tunnel tests to support the theory that the so-called Australasian tektites originated from the Rosse ejecta ray of the large crater Tycho on the Moon's nearside. Until the Rosse ray is sampled, a lunar origin for these tektites cannot be ruled out.

In 1969 a concentration of [meteorite]s was found on Antarctica by a Japanese exploration team. Since then, tens of thousands of meteorites have been found, among which those from the Moon have been identified. Together with Apollo and Luna samples returned from the Moon, these lunar meteorites have been helping scientists study the origin and evolution of the Moon.

Legal status

Though several flags of the Soviet Union and the United States have been symbolically planted on the moon, the Russian and U.S. governments make no claims to any part of the Moon's surface. Russia and the US are party to the Outer Space Treaty, which places the Moon under the same jurisdiction as international waters (res communis). This treaty also restricts use of the Moon to peaceful purposes, explicitly banning weapons of mass destruction (including nuclear weapons) and military installations of any kind. A second treaty, the Moon Treaty, was proposed to restrict the exploitation of the Moon's resources by any single nation, but it has not been signed by any of the space-faring nations.

Several individuals have made claims to the Moon in whole or in part, though none of these claims are generally considered credible.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Onasch, Bernd (2006). Moon. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

- ↑ Moon Fact Sheet. NSSDC. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

- ↑ Jones, J H. Tests of the giant impact hypothesis. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ Kleine, Thorsten and Herbert Palme, Klaus Mezger, Alex N. Halliday (9 December 2005). Hf-W Chronometry of Lunar Metals and the Age and Early Differentiation of the Moon. Science 310 (5754): 1671 - 1674.

- ↑ J. Levine, T. A. Becker, R. A. Muller, P. R. Renne. 40Ar/39Ar dating of Apollo 12 impact spherules. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32,: L15201.

- ↑ T. S. Culler, T. A. Becker, R. A. Muller, P. R. Renne (2000). Lunar Impact History from 40Ar/39Ar Dating of Glas Spherules. Science 287: 1785-1788.

- ↑ Clementine Images on the Moon. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

- ↑ Lunar Polar Composites (GIF). Retrieved 2006-03-20.

- ↑ Moon Water. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ↑ Spekkens, Kristine (October 2002). Is the Moon seen as a crescent (and not a "boat") all over the world?. Curious About Astronomy. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

Additional references

- Ben Bussey and Paul Spudis, The Clementine Atlas of the Moon, Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0521815282.

- Patrick Moore, On the Moon, Sterling Publishing Co., 2001 edition, ISBN 0304354694.

- Paul D. Spudis, The Once and Future Moon, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996, ISBN 1-56098-634-4.

- Klein, T., Palme, H., Mezger, M., Halliday, A. N., 2005. Hf-W chronometry of lunar metals and the age and early differentiation of the moon. Science, v.310(5754) 1671-1674.

- Crust composition selected from Ahrens, Global Earth Physics : A Handbook of Physical Constants, American Geophysical Union (1995). ISBN 0875908519

External links

Moon phases

- Full Moon Names

- US Naval Observatory: phase of the Moon for any date and time 1800-2199 C.E.

- Current Moon Phase

- Display current moon phase as wallpaper in Windows

Space missions

- The Apollo Lunar Surface Journal (NASA) — Definitive history of Apollo lunar exploration programme.

- Assembled Panoramas from the Apollo Missions

- Digital Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon

- The Project Apollo Archive

- Clementine Lunar Image Browser

- 04/28/06: NASA Exploration Workshop: Strategy Development for Return to the Moon

- JAXA SELENE Mission

- Chandrayaan I Mission

Scientific

- The Moon – by Rosanna and Calvin Hamilton

- The Moon – by Bill Arnett

- Inconstant Moon – by Kevin Clarke

- Geologic History of the Moon by Don Wilhelms

- Origin of the Moon - computer model of accretion subsequent to computer model of collision

- Can you put the moon into orbit? An interactive (creationist) simulation (Requires Firefox 1.5)

- 10/19/05: Hubble Looks for Possible Moon Resources.

- NASA Chooses New Spacecraft to Search for Water on the Moon

Others

- The Moon Society (non-profit educational site)

- USGS Planetary GIS webserver – the Moon

- Why does the Moon appear bigger near the horizon? (from The Straight Dope)

- Bad Astronomy: Dr. Philip Plait, an astronomy professor at Sonoma State University, California, runs this site to explain the many cases of incorrect astronomy (and physics) available to the public, including astrology and the Apollo moon landing hoax accusations.

- The Lunar Navigator: Interactive Maps Of The Moon features free, interactive online access to maps of the Moon's surface

- A comprehensive guide to the Earth's Moon – moonpeople.com (Includes a discussion forum)

- 3D VRML Moon globe

- 3D maps of Moon in NASA World Wind

- Google Moon A view of the moon, including a reference to the myth that the moon is made of cheese.

- The Two Sides of the Moon An ABC Science online feature: Geoscientific debate about the origins of the Moon

- Lunar Photo of the Day Lunar scientist Charles A. Wood's lunar counterpart to the Astronomy Picture of the Day

- Corkscrew Asteroids (PhysOrg.com), Asteroid 2003 YN107 as Earth's "second moon"

- Space.com: All About the Moon Moon Reference and News

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.