Difference between revisions of "Nonviolence" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (109 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

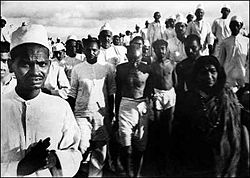

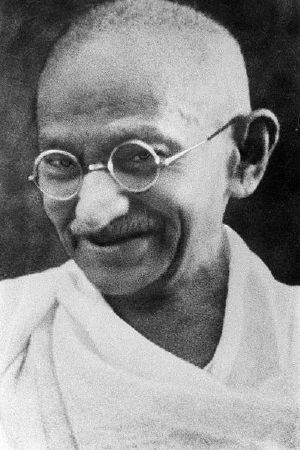

[[File:Portrait Gandhi.jpg|thumb|[[Mahatma Gandhi|Mohandas Gandhi]], often considered a founder of the nonviolence movement, spread the concept of [[ahimsa]] through his movements and writings, which then inspired other nonviolent activists.]] | [[File:Portrait Gandhi.jpg|thumb|[[Mahatma Gandhi|Mohandas Gandhi]], often considered a founder of the nonviolence movement, spread the concept of [[ahimsa]] through his movements and writings, which then inspired other nonviolent activists.]] | ||

| − | '''Nonviolence''' is the | + | '''Nonviolence''' is the practice of being harmless to self and others under every condition. It comes from the belief that hurting people, animals, or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and refers to a general philosophy of abstention from violence. This may be based on moral, religious, or spiritual principles, or it may be for purely strategic or pragmatic reasons. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Forms of nonviolence draw inspiration from both religious or ethical beliefs and political analysis. Religious or ethically based nonviolence is sometimes referred to as ''principled,'' ''philosophical,'' or ''ethical'' nonviolence, while nonviolence based on political analysis is often referred to as ''tactical,'' ''strategic,'' or ''pragmatic'' nonviolent action. Both of these dimensions may be present within the thinking of particular movements or individuals. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Nonviolence also has "active" or "activist" elements, in that believers generally accept the need for nonviolence as a means to achieve political and [[social change]]. Thus, for example, the nonviolence of [[Tolstoy]] and [[Gandhi]] is a philosophy and strategy for social change that rejects the use of [[violence]], but at the same time sees [[nonviolent action]] (also called [[civil resistance]]) as an alternative to passive acceptance of oppression or armed struggle against it. In general, advocates of an activist philosophy of nonviolence use diverse methods in their campaigns for social change, including critical forms of education and persuasion, mass noncooperation, [[civil disobedience]], nonviolent [[direct action]], and social, political, cultural, and economic forms of intervention. | ||

| − | + | ==History== | |

| + | Nonviolence or ''[[Ahimsa]]'' is one of the cardinal virtues<ref name=evpc/> and an important tenet of [[Jainism]], [[Hinduism]], and [[Buddhism]]. It is a multidimensional concept, inspired by the premise that all living beings have the spark of the divine spiritual energy.<ref name=arapura>K.R. Sundararajan and Bithika Mukerji (eds.), ''Hindu Spirituality: Postclassical and Modern'' (Herder & Herder, 1997, ISBN 978-0824516710).</ref> Therefore, to hurt another being is to hurt oneself. It has also been related to the notion that any violence has [[Karma|karmic]] consequences. | ||

| − | + | While ancient scholars of Hinduism pioneered and over time perfected the principles of ''Ahimsa'', the concept reached an extraordinary status in the ethical philosophy of Jainism.<ref name=evpc>Lester R. Kurtz (ed.), ''Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, and Conflict'' (Academic Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0123695031).</ref><ref name=Chapple> Christopher Chapple, ''Non-violence to Animals, Earth and Self in Asian Traditions'' (Sri Satguru Publications, 1995, ISBN 978-8170304265).</ref> According to Jain mythology, the first ''[[tirthankara]]'', [[Rishabhanatha|Rushabhdev]], originated the idea of nonviolence over a million years ago.<ref>Haresh Patel, ''Thoughts from the Cosmic Field in the Life of a Thinking Insect [A Latter-Day Saint]'' (Eloquent Books, 2009, ISBN 978-1606938461).</ref> Historically, [[Parsvanatha]], the twenty-third ''tirthankara'' of Jainism, advocated for and preached the concept of nonviolence in around the eighth century B.C.E. [[Mahavira]], the twenty-fourth and last ''tirthankara'', then further strengthened the idea in the sixth century B.C.E. | |

| − | + | The idea of using nonviolent methods to achieve social and political change has been expressed in Western society over the past several hundred years: [[Étienne de La Boétie]]'s ''[[Discourse on Voluntary Servitude]]'' (sixteenth century) and [[Percy Bysshe Shelley|P.B. Shelley's]] ''[[The Masque of Anarchy]]'' (1819) contain arguments for resisting tyranny without using violence, while in 1838, [[William Lloyd Garrison]] helped found the [[Non-Resistance Society|New England Non-Resistance Society]], a society devoted to achieving racial and gender equality through the rejection of all violent actions.<ref>Nicolas Walter, David Goodway (ed.), ''Damned Fools in Utopia and Other Writings on Anarchism and War Resistance'' (PM Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1604862225).</ref> | |

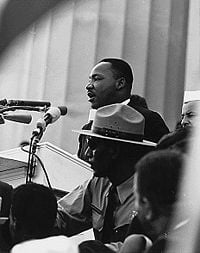

| − | [[ | + | In modern times, nonviolent methods of action have become a powerful tool for social protest and revolutionary social and political change.<ref name=evpc/><ref>Mark Kurlansky, ''Nonviolence: The History of a Dangerous Idea'' (Modern Library, 2008, ISBN 978-0812974478).</ref> For example, [[Mohandas K. Gandhi|Mahatma Gandhi]] led a successful decades-long nonviolent struggle against [[British Raj|British rule in India]]. [[Martin Luther King]] and [[James Bevel]] adopted Gandhi's nonviolent methods in their campaigns to win [[civil rights]] for [[African American]]s. [[César Chávez]] led campaigns of nonviolence in the 1960s to protest the treatment of farm workers in California. The 1989 "[[Velvet Revolution]]" in [[Czechoslovakia]] that saw the overthrow of the [[Communist]] government is considered one of the most important of the largely nonviolent [[Revolutions of 1989]]. |

| + | [[File:Non-Violence sculpture in front of UN headquarters NY.JPG|thumb|right|250px|The sculpture "Nonviolence" by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd in front of the [[United Nations]] Headquarters in [[New York City]]]] | ||

| + | Nonviolence has obtained a level of institutional recognition and endorsement at the global level. On November 10, 1998, the [[United Nations]] General Assembly proclaimed the first decade of the twenty-first century and the third millennium, the years 2001 to 2010, as the International Decade for the Promotion of a Culture of Peace and Non-Violence for the Children of the World].<ref>[https://www.un.org/en/ga/62/plenary/peaceculture/bkg.shtml Culture of peace] General Assembly of the United Nations, 62nd session. Retrieved January 8, 2020.</ref> | ||

==Ethical nonviolence== | ==Ethical nonviolence== | ||

| − | [[File:Semai - remaja.jpg|thumb|The Semai have | + | [[File:Semai - remaja.jpg|thumb|250px|The Semai people of [[Malaysia]] have a belief called ''[[punan]]'', which includes nonviolence]] |

| − | For many, practicing nonviolence goes deeper than abstaining from violent behavior or words. It means overriding the impulse to be hateful and holding love for everyone, even those with whom one strongly disagrees. In this view, because violence is learned, it is necessary to unlearn violence by practicing love and compassion at every possible opportunity. | + | For many, practicing nonviolence goes deeper than abstaining from [[violence|violent]] behavior or words. It means overriding the impulse to be hateful and holding [[love]] for everyone, even those with whom one strongly disagrees. In this view, because violence is learned, it is necessary to unlearn violence by practicing love and compassion at every possible opportunity. For some, the commitment to nonviolence entails a belief in restorative or [[transformative justice]] and the abolition of the [[death penalty]] and other harsh punishments. This may involve the necessity of caring for those who are violent. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Nonviolence, for many, involves a respect and reverence for all [[sentience|sentient]], and perhaps even non-sentient, beings. This might include the belief that all sentient beings share the basic right not to be treated as the [[property]] of others, the practice of not eating animal products or by-products ([[vegetarianism]] or [[veganism]]), spiritual practices of [[Ahimsa|non-harm]] to all beings, and caring for the rights of all beings. [[Mohandas Gandhi]], [[James Bevel]], and other nonviolent proponents advocated vegetarianism as part of their nonviolent philosophy. [[Buddhists]] extend this respect for [[life]] to [[animals]] and [[plants]], while [[Jains]] extend it to [[animals]], [[plants]], and even small organisms such as [[insects]]. | |

==Religious nonviolence== | ==Religious nonviolence== | ||

| − | ''[[Ahimsa]]'' is a Sanskrit term meaning "nonviolence" or "non-injury" (literally: the avoidance of himsa: violence). The principle of ahimsa is central to the religions of [[Hinduism]], [[Jainism]], and [[Buddhism]], being a key precept in their ethical codes. | + | ''[[Ahimsa]]'' is a Sanskrit term meaning "nonviolence" or "non-injury" (literally: the avoidance of himsa: violence). The principle of ahimsa is central to the religions of [[Hinduism]], [[Jainism]], and [[Buddhism]], being a key precept in their ethical codes.<ref> Claudia Eppert and Hongyu Wang (eds.), ''Cross-Cultural Studies in Curriculum: Eastern Thought, Educational Insights'' (Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-1843153665).</ref> It implies the total avoidance of harming of any kind of living creatures not only by deeds, but also by words and in thoughts. |

===Hinduism=== | ===Hinduism=== | ||

| − | The [[Hindu]] scriptures contain mixed messages on the necessity and scope of nonviolence in human affairs. Some texts insist that ahimsa is the highest duty while other texts make exceptions in the cases of | + | The [[Hindu]] scriptures contain mixed messages on the necessity and scope of nonviolence in human affairs. Some texts insist that ''[[ahimsa]]'' is the highest duty, while other texts make exceptions in the cases of [[war]], [[hunting]], ruling, [[law enforcement]], and [[capital punishment]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Ahimsa]] as an ethical concept evolved in the Vedic texts.<ref name=Chapple/><ref> Koshelya Walli, ''The Conception of Ahimsa in Indian Thought'' (Bharata Manisha, 1974).</ref> The oldest scripts, along with discussing ritual animal sacrifices, indirectly mention ahimsa, but do not emphasize it. Over time, the concept of ahimsa was increasingly refined and emphasized, ultimately becoming the highest virtue by the late Vedic era (about 500 B.C.). | |

| − | + | The [[Mahabharata]], one of the epics of Hinduism, has multiple mentions of the phrase ''Ahimsa Paramo Dharma'' (अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मः), which literally means: nonviolence is the highest moral virtue. For example, [[Mahaprasthanika Parva]] has the following verse emphasizes the cardinal importance of Ahimsa in Hinduism:<ref>[https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/mbs/mbs13117.htm Mahabharata 13.117.37–38] ''The Mahabharata in Sanskrit''. Retrieved January 2, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | + | <blockquote> | |

| − | + | :अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मस तथाहिंसा परॊ दमः। | |

| − | + | :अहिंसा परमं दानम अहिंसा परमस तपः। | |

| − | + | :अहिंसा परमॊ यज्ञस तथाहिस्मा परं बलम। | |

| − | + | :अहिंसा परमं मित्रम अहिंसा परमं सुखम। | |

| − | + | :अहिंसा परमं सत्यम अहिंसा परमं शरुतम॥ | |

| − | The [[Mahabharata]], one of the epics of Hinduism, has multiple mentions of the phrase ''Ahimsa Paramo Dharma'' (अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मः), which literally means: | + | </blockquote> |

| − | <blockquote | + | The literal translation is as follows: |

| − | अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मस तथाहिंसा परॊ दमः। | + | <blockquote> |

| − | अहिंसा परमं दानम अहिंसा परमस तपः। | + | :Ahimsa is the highest virtue, Ahimsa is the highest self-control, |

| − | अहिंसा परमॊ यज्ञस तथाहिस्मा परं बलम। | + | :Ahimsa is the greatest gift, Ahimsa is the best suffering, |

| − | अहिंसा परमं मित्रम अहिंसा परमं सुखम। | + | :Ahimsa is the highest sacrifice, Ahimsa is the finest strength, |

| − | अहिंसा परमं सत्यम अहिंसा परमं शरुतम॥ | + | :Ahimsa is the greatest friend, Ahimsa is the greatest happiness, |

| − | </ | + | :Ahimsa is the highest truth, and Ahimsa is the greatest teaching.<ref name=ecological>Christopher Chapple, "Ecological Nonviolence and the Hindu Tradition" In V.K. Kool, (ed.). ''Perspectives on Nonviolence'' (Springer New York, 2011, ISBN 978-1461287834).</ref></blockquote> |

| − | + | Some other examples where the phrase ''Ahimsa Paramo Dharma'' are discussed include [[Adi Parva]], [[Vana Parva]], and [[Anushasana Parva]]. The [[Bhagavad Gita]] discusses the doubts and questions about appropriate response when one faces systematic violence or war. These verses develop the concepts of lawful violence in self-defense and the [[Just war theory|theories of just war]]. However, there is no consensus on this interpretation. Gandhi, for example, considered this debate about nonviolence and lawful violence as a mere metaphor for the internal war within each human being, when he or she faces moral questions.<ref> | |

| + | Louis Fischer, ''Gandhi: His Life and Message to the World'' (Signet, 2010, ISBN 978-0451531704).</ref> | ||

====Self-defense, criminal law, and war==== | ====Self-defense, criminal law, and war==== | ||

| − | The classical texts of Hinduism devote numerous chapters | + | The classical texts of Hinduism devote numerous chapters to discussion of what people who practice the virtue of Ahimsa can and must do when they are faced with [[war]], violent threat, or need to sentence someone convicted of a [[crime]]. These discussions have led to theories of [[just war]], theories of reasonable [[self-defense]], and theories of proportionate punishment.<ref name=klos1996>Klaus K. Klostermaier, "Himsa and Ahimsa Traditions in Hinduism" in Harvey L. Dyck (ed.), ''The Pacifist Impulse in Historical Perspective'' (University of Toronto Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0802007773).</ref> [[Arthashastra]] discusses, among other things, why and what constitutes proportionate response and punishment.<ref name=robinson2003>Paul F. Robinson (ed.), ''Just War in Comparative Perspective'' (Routledge, 2003, ISBN 978-0754635871).</ref> |

;War | ;War | ||

| − | The precepts of Ahimsa | + | The precepts of Ahimsa in Hinduism require that war must be avoided if at all possible, with sincere and truthful dialogue. Force must be the last resort. If war becomes necessary, its cause must be just, its purpose virtuous, its objective to restrain the wicked, its aim peace, its method lawful.<ref name=robinson2003/> War can only be started and stopped by a legitimate authority. Weapons used must be proportionate to the opponent and the aim of war, not indiscriminate tools of destruction. All strategies and weapons used in the war must be to defeat the opponent, not designed to cause misery to them; for example, use of arrows is allowed, but use of arrows smeared with painful poison is not allowed. Warriors must use judgment in the battlefield. Cruelty to the opponent during war is forbidden. Wounded, unarmed opponent warriors must not be attacked or killed, they must be brought to safety and given medical treatment.<ref name=robinson2003/> Children, women and civilians must not be injured. While the war is in progress, sincere dialogue for peace must continue.<ref name=klos1996/> |

;Self-defense | ;Self-defense | ||

| − | In matters of self- | + | In matters of self-defense, different interpretations of ancient Hindu texts have been offered, such as that self-defense is appropriate, criminals are not protected by the rule of Ahimsa, and Hindu scriptures support the use of violence against an armed attacker.<ref name=Tahtinen> Unto Tähtinen, ''Ahimsa: Non-violence in Indian Tradition'' (Rider, 1976, ISBN 978-0091233402).</ref><ref>Mahabharata 12.15.55; Manu Smriti 8.349–350; Matsya Purana 226.116.</ref> Ahimsa does not imply [[pacifism]].<ref name=Tahtinen/> |

| − | + | Inspired by Ahimsa, principles of self-defense have been developed in the martial arts. [[Morihei Ueshiba]], the founder of [[Aikido]], described his inspiration as ahimsa.<ref>Nebojša Vasic, [http://www.sportspa.com.ba/images/dec2011/full/rad8.pdf The Role of Teachers in Martial Arts] ''Sport SPA'' 8(2) (2011): 47-51. Retrieved January 2, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | ; Criminal law | + | ;Criminal law |

| − | + | Some have concluded that Hindus have no misgivings about the [[death penalty]]. Their position is that evil-doers who deserve death should be killed, and that a king in particular is obliged to punish criminals and should not hesitate to kill them, even if they happen to be his own brothers and sons.<ref name=Tahtinen/> | |

| − | Other scholars | + | Other scholars have concluded that the scriptures of Hinduism suggest sentences for any crime must be fair, proportionate, and not cruel.<ref name=klos1996/><ref name=robinson2003/> |

====Non-human life==== | ====Non-human life==== | ||

| − | + | Across the texts of Hinduism, there is a profusion of ideas about the virtue of ahimsa when applied to non-human life, but without universal consensus. | |

| − | + | This precept is not found in the oldest verses of Vedas, but increasingly becomes one of the central ideas between 500 B.C.E. and 400 C.E.<ref name=Chapple/> In the oldest texts, numerous ritual sacrifices of animals, including cows and horses, are highlighted and hardly any mention is made of ahimsa in relation to non-human life.<ref>D.N. Jha, ''The Myth of the Holy Cow'' (Verso, 2004, ISBN 978-1859844243).</ref> However, the ancient Hindu texts discourage wanton destruction of nature, including wild and cultivated plants. Hermits ([[sannyasa|sannyasin]]s) were urged to live on a [[fruitarian]] diet so as to avoid the destruction of plants.<ref>Rod Preece, ''Animals and Nature: Cultural Myths, Cultural Realities'' (University of British Columbia Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0774807241).</ref> | |

| − | + | Hindu scriptures dated to between the fifth century and first century B.C.E., in discussing human diet, initially suggest ''kosher'' meat may be eaten, suggesting that only meat obtained through ritual sacrifice can be eaten. This evolved into the belief that one should eat no meat because it hurts animals, with verses describing the noble life as one that lives on flowers, roots, and fruits alone.<ref name=Chapple/> | |

| − | + | Later Hindu texts declare Ahimsa one of the primary [[virtue]]s, and that killing or harming any life to be against ''dharma'' (moral life). Finally, the discussion in the [[Upanishads]] and the Hindu epics shifts to whether a human being can ever live his or her life without harming animal and plant life in some way; which and when plants or animal meat may be eaten, whether violence against animals causes human beings to become less compassionate, and if and how one may exert least harm to non-human life consistent with ahimsa, given the constraints of life and human needs. | |

| − | Many of the arguments proposed in favor of | + | Many of the arguments proposed in favor of nonviolence to animals refer to the bliss one feels, the rewards it entails before or after death, the danger and harm it prevents, as well as to the karmic consequences of violence.<ref name=Tahtinen/> For example, ''[[Tirukkuṛaḷ]],'' written between 200 B.C. and 400 C.E., says that Ahimsa applies to all life forms. It dedicates several chapters to the virtue of ahimsa, namely, [[moral vegetarianism]], non-harming, and [[non-killing]], respectively.<ref> G.U. Pope, ''Tirukkural: English Translation and Commentary'' (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017, ISBN 978-1975616724).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Jainism=== | ===Jainism=== | ||

| + | [[file:Ahimsa Jainism Gradient.jpg|thumb|150px|The hand with a wheel on the palm symbolizes the Jain Vow of Ahimsa. The word in the middle is "Ahimsa." The wheel represents the [[dharmacakra]] which stands for the resolve to halt the cycle of reincarnation through relentless pursuit of truth and nonviolence.]] | ||

| + | In [[Jainism]], the understanding and implementation of ''Ahimsā'' is more radical, scrupulous, and comprehensive than in any other religion. The statement ''{{IAST|ahimsā paramo dharmaḥ}}'' is often found inscribed on the walls of the [[Jain temple]]s.<ref name=Dundas>Paul Dundas, ''The Jains'' (Routledge, 2002, ISBN 978-0415266062).</ref><ref> Peter Flugel (ed.), ''Studies in Jaina History and Culture'' (Routledge, 2006, ISBN 978-0415360999).</ref> Killing any living being out of passion is considered ''hiṃsā'' (to injure) and abstaining from such an act is ''ahimsā'' (noninjury).<ref name=Vijay>Vijay K. Jain, ''Acharya Amritchandra's Purusartha Siddhi Upaya'' (Vikalp Printers, 2012, ISBN 978-8190363945). </ref> Like in Hinduism, the aim is to prevent the accumulation of harmful karma. | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Mahatma Gandhi]] expressed the view: |

| − | + | <blockquote>No religion in the world has explained the principle of ''Ahimsa'' so deeply and systematically as is discussed with its applicability in every human life in Jainism. As and when the benevolent principle of ''Ahimsa'' or non-violence will be ascribed for practice by the people of the world to achieve their end of life in this world and beyond. Jainism is sure to have the uppermost status and Lord Mahavira is sure to be respected as the greatest authority on ''Ahimsa''.<ref> Janardan Pandey (ed.), ''Gandhi and 21st Century'' (Concept Publishing Company, 1998, ISBN 978-8170226727).</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | The | + | The vow of ahimsā is considered the foremost among the five vows of Jainism. Other vows like truth (Satya) are meant for safeguarding the vow of ahimsā.<ref name=Vijay/> In the practice of Ahimsa, the requirements are less strict for the lay persons ([[sravakas]]) who have undertaken ''anuvrata'' (Smaller Vows) than for the [[Jain monasticism|Jain monastics]] who are bound by the [[Mahavrata]] "Great Vows."<ref>Kerry S. Walters and Lisa Portmess (eds.). ''Religious Vegetarianism: From Hesiod to the Dalai Lama'' (SUNY Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0791449721).</ref> |

| − | Theoretically, all life forms are said to deserve full protection from all kinds of injury, but Jains | + | The Jain concept of Ahimsa is characterized by several aspects. Theoretically, all life forms are said to deserve full protection from all kinds of injury, but Jains recognize a hierarchy of life. Mobile beings are given higher protection than immobile ones. Among mobile beings, they distinguish between one-sensed, two-sensed, three-sensed, four-sensed, and five-sensed ones; a one-sensed animal having touch as its only sensory modality. The more senses a being has, the more care they receive. |

| − | Jains | + | Jains do not make any exception for ritual sacrifice and professional warrior-hunters. Killing of animals for food is absolutely ruled out.<ref name=Tahtinen/> Jains also make considerable efforts not to injure plants in everyday life as far as possible. Though they admit that plants must be destroyed for the sake of food, they accept such violence only inasmuch as it is indispensable for human survival, and there are special instructions for preventing unnecessary violence against plants. Jains go out of their way so as not to hurt even small insects and other minuscule animals. Some Jains abstain from farming because it inevitably entails unintentional killing or injuring of many small animals, such as worms and insects, but agriculture is not forbidden in general and there are Jain farmers.<ref name=Dundas/> |

===Buddhism=== | ===Buddhism=== | ||

| − | The traditional Buddhist understanding of nonviolence is not as rigid as the Jain one. | + | The traditional [[Buddhist]] understanding of nonviolence is not as rigid as the Jain one. In Buddhist texts ''Ahimsa'' (or its [[Pāli]] cognate {{IAST|avihiṃsā}}) is part of the [[Five Precepts]] ({{IAST|Pañcasīla}}), the first of which is to abstain from killing. This precept of Ahimsa is applicable to both the Buddhist layperson and the monk community.<ref>Paul Williams, ''Buddhism: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies'' (Routledge, 2006, ISBN 0415332265).</ref> |

| − | In Buddhist texts ''Ahimsa'' (or its [[Pāli]] cognate {{IAST|avihiṃsā}}) is part of the [[Five Precepts]] ({{IAST|Pañcasīla}}), the first of which | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Ahimsa precept is not a commandment and transgressions did not invite religious sanctions for laypersons, but its power is in the Buddhist belief in [[karma|karmic]] consequences and their impact in the [[afterlife]] during rebirth.<ref name=Harvey>Peter Harvey, ''An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices'' (Cambridge University Press, 2012, ISBN 0521676746).</ref> Killing, in Buddhist belief, could lead to rebirth in the hellish realm, and for a longer time in more severe conditions if the murder victim was a monk.<ref name=Harvey/> Saving animals from slaughter for meat is believed to be a way to acquire merit for better rebirth. These moral precepts have been voluntarily self-enforced in lay Buddhist culture through the associated belief in karma and rebirth.<ref name=Harvey/> The Buddhist texts not only recommend Ahimsa, but suggest avoiding trading goods that contribute to or are a result of violence: | |

| − | These five trades, O monks, should not be taken up by a lay follower: trading with weapons, trading in living beings, trading in meat, trading in intoxicants, trading in poison. | + | <blockquote>These five trades, O monks, should not be taken up by a lay follower: trading with weapons, trading in living beings, trading in meat, trading in intoxicants, trading in poison.<ref> Martine Batchelor, ''The Spirit of the Buddha'' (Yale University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0300164077).</ref></blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | Unlike lay Buddhists, transgressions by monks do invite sanctions. | + | Unlike lay Buddhists, transgressions by monks do invite sanctions. Full expulsion of a monk from ''sangha'' follows instances of killing, just like any other serious offense against the monastic ''nikaya'' code of conduct.<ref name=Harvey/> |

=====War===== | =====War===== | ||

| − | Violent ways of punishing criminals and prisoners of war | + | Violent ways of punishing criminals and [[prisoners of war]] are not explicitly condemned in Buddhism, but peaceful ways of conflict resolution and punishment with the least amount of injury are encouraged.<ref>Kurt A. Raaflaub, ''War and Peace in the Ancient World''] (Wiley-Blackwell, 2006, ISBN 978-1405145268).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | While the early texts condemn killing in the strongest terms, and portray the ideal king as a pacifist, such a king is nonetheless flanked by an army.<ref name=Bartholomeusz>Tessa J. Bartholomeusz, ''In Defense of Dharma'' (Routledge, 2002, ISBN 978-0700716821).</ref> It seems that the Buddha's teaching on nonviolence was not interpreted or put into practice in an uncompromisingly pacifist or anti-military-service way by early Buddhists. The early texts assume war to be a fact of life, and well-skilled warriors are viewed as necessary for defensive warfare.<ref name=Bartholomeusz/> In Pali texts, injunctions to abstain from violence and involvement with military affairs are directed at members of the [[Sangha (Buddhism)|sangha]]; later Mahayana texts, which often generalize monastic norms to laity, require this of lay people as well.<ref>Peter Harvey (ed.), ''Buddhism'' (Bloomsbury Academic, 2001, ISBN 978-0826453518).</ref> | |

| − | + | The early texts do not contain just-war ideology as such. Some argue that a [[suttas|sutta]] in the ''Gamani Samyuttam'' rules out all military service. In this passage, a soldier asks the Buddha if it is true that, as he has been told, soldiers slain in battle are reborn in a heavenly realm. The Buddha reluctantly replies that if he is killed in battle while his mind is seized with the intention to kill, he will undergo an unpleasant rebirth.<ref name=Bartholomeusz/> In the early texts, a person's mental state at the time of death is generally viewed as having a great impact on the next birth.<ref>Rune E.A. Johansson, ''The Dynamic Psychology of Early Buddhism'' (Curzon Press, 1979, ISBN 978-0700701148).</ref> | |

| − | + | Some Buddhists point to other early texts as justifying defensive war.<ref>Some examples are the ''Cakkavati Sihanada Sutta'', the ''Kosala Samyutta'', the ''Ratthapala Sutta'', and the ''Sinha Sutta''. </ref> In the ''Kosala Samyutta'', King [[Pasenadi]], a righteous king favored by the Buddha, learns of an impending attack on his kingdom. He arms himself in defense, and leads his army into battle to protect his kingdom from attack. He lost this battle but won the war. King Pasenadi eventually defeated King [[Ajatasattu]] and captured him alive. He thought that, although this King of [[Magadha]] had transgressed against his kingdom, he had not transgressed against him personally, and Ajatasattu was still his nephew. He released Ajatasattu and did not harm him.<ref> Bhikkhu Bodhi (trans.), ''The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya'' (Wisdom Publications, 2003, ISBN 978-0861713318).</ref> Upon his return, the Buddha said that Pasenadi "is a friend of virtue, acquainted with virtue, intimate with virtue," while the opposite is said of the aggressor, King Ajatasattu.<ref name=Bartholomeusz/> | |

| − | According to | + | According to Theravada commentaries, there are five requisite factors that must all be fulfilled for an act to be both an act of killing and to be karmically negative. These are: (1) the presence of a living being, human or animal; (2) the knowledge that the being is a living being; (3) the intent to kill; (4) the act of killing by some means; and (5) the resulting death.<ref>Hammalawa Saddhatissa, ''Buddhist Ethics'' (Wisdom Publications, 1997, ISBN 978-0861711246). </ref> Some Buddhists have argued on this basis that the act of killing is complicated, and its ethicization is predicated upon intent. In defensive postures, for example, the primary intention of a soldier is not to kill, but to defend against aggression, and the act of killing in that situation would have minimal negative karmic repercussions.<ref name=Bartholomeusz/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Pragmatic nonviolence== | ==Pragmatic nonviolence== | ||

| − | The fundamental concept of ''pragmatic'' (''tactical'' or ''strategic'') nonviolent action is to | + | The fundamental concept of '''pragmatic''' ('''tactical''' or '''strategic''') nonviolent action is to effect [[social change]] by mobilizing "people-power while at the same time limiting and restricting the ability of opponents to suppress the movement with violence and money-power."<ref> Bruce Hartford, [http://www.crmvet.org/info/nvpower.htm Nonviolent Resistance & Political Power] 2008. Retrieved January 5, 2020.</ref> |

| − | [[ | + | Social change is to be achieved through [[symbol]]ic [[protest]]s, [[civil disobedience]], economic or political noncooperation, [[satyagraha]], or other methods, while being nonviolent. This type of action highlights the desires of an individual or group that something needs to change to improve the current condition of the resisting person or group. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In modern industrial democracies, nonviolent action has been used extensively by political sectors | + | Advocates of nonviolent action believe cooperation and consent are the roots of civil or political power: all regimes, including bureaucratic institutions, financial institutions, and the armed segments of society (such as the [[military]] and [[police]]) depend on compliance from citizens.<ref name=SharpPolitics/> On a national level, the strategy of nonviolent action seeks to undermine the power of rulers by encouraging people to withdraw their consent and cooperation. |

| + | [[File:Gandhi at Dandi 5 April 1930.jpg|thumb|200px|Gandhi used the weapon of nonviolence against [[British Raj]] in the Salt March, 1930.]] | ||

| + | In modern industrial democracies, nonviolent action has been used extensively by political sectors lacking mainstream political power, such as labor, peace, environment, and women's movements. Examples of such movements are the [[Non-cooperation movement|non-cooperation campaign]] for [[Indian independence movement|Indian independence]] led by [[Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi]], the [[Civil Rights Movement]] in the [[United States]], and the [[People Power Revolution]] in the [[Philippines]]. In addition to Gandhi, major nonviolent resistance advocates include [[Henry David Thoreau]], [[Te Whiti o Rongomai]], [[Tohu Kākahi]], [[Leo Tolstoy]], [[Alice Paul]], [[Martin Luther King, Jr.|Martin Luther King, Jr]], [[Daniel Berrigan]], [[Philip Berrigan]], [[James Bevel]], [[Václav Havel]], [[Andrei Sakharov]], [[Lech Wałęsa]], [[Gene Sharp]], and [[Nelson Mandela]]. | ||

| − | + | Of primary significance in nonviolent action is the understanding that just means are the most likely to lead to just ends. Proponents of nonviolence reason that the actions taken in the present inevitably re-shape the social order in like form. They would argue, for instance, that it is fundamentally irrational to use violence to achieve a peaceful society. For instance, [[Gandhi]] wrote in 1908 that "The means may be likened to a seed, the end to a tree; and there is just the same inviolable connection between the means and the end as there is between the seed and the tree."<ref> Mohandas K. Gandhi, ''Hind Swaraj Or Indian Home Rule'' (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2009, ISBN 978-1449922214).</ref> [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]], a student of Gandhian nonviolent resistance, concurred with this tenet in his letter from the Birmingham jail, concluding that "nonviolence demands that the means we use must be as pure as the ends we seek."<ref>Martin Luther King, Jr., [https://genius.com/Martin-luther-king-jr-letter-from-birmingham-jail-annotated Letter From Birmingham Jail] Retrieved January 8, 2020.</ref> | |

| + | [[File:Martin Luther King - March on Washington.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Martin Luther King]] speaking at the 1963 "[[March on Washington]]".]] | ||

| − | + | The term "nonviolence" is often wrongly equated with passivity and [[pacifism]], but this is incorrect.<ref>Peter Ackerman and Jack DuVall, ''A Force More Powerful: A Century of Non-violent Conflict'' (St. Martin's Griffin, 2000, ISBN 978-0312240509).</ref> Nonviolence refers specifically to the absence of violence and is the choice to do no harm or the least harm, while passivity is the choice to do nothing. [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] explained that nonviolence is an active weapon: | |

| + | <blockquote>Nonviolence is a powerful and just weapon. Indeed, it is a weapon unique in history, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.<ref>Martin Luther King, Jr., [https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/lecture/ The Quest for Peace and Justice] The Nobel Peace Prize Lecture, 1964. Retrieved January 7, 2020.</ref> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Respect or love for opponents also has a pragmatic justification, in that the technique of separating the deeds from the doers allows for the possibility of the doers changing their behavior, and perhaps their beliefs. [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] wrote, "Nonviolent resistance... avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent, but he also refuses to hate him."<ref>Martin Luther King, Jr., ''Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story'' (Beacon Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0807000694).</ref> | |

| − | [[ | + | Finally, the notion of ''[[Satya]]'', or Truth, is central to the Gandhian conception of nonviolence. Gandhi saw Truth as something that is multifaceted and unable to be grasped in its entirety by any one individual. All carry pieces of the Truth, he believed, but all need the pieces of others’ truths in order to pursue the greater Truth. This led him to believe in the inherent worth of dialogue with opponents, in order to understand motivations. |

| − | + | Nonviolent action generally comprises three categories: Acts of Protest and Persuasion, Noncooperation, and Nonviolent Intervention.<ref>[https://www.un.org/en/events/nonviolenceday/background.shtml Background] ''International Day of Nonviolence'', United Nations. Retrieved January 8, 2020,</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Nonviolent action generally comprises three categories: | ||

| + | ===Acts of protest=== | ||

[[File:Gandhi Salt March.jpg|thumb|250px|right|The [[Salt Satyagraha|Salt March]] on March 12, 1930]] | [[File:Gandhi Salt March.jpg|thumb|250px|right|The [[Salt Satyagraha|Salt March]] on March 12, 1930]] | ||

| − | + | Nonviolent acts of protest and persuasion are symbolic actions performed by a group of people to show their support or disapproval of something. The goal of this kind of action is to bring public awareness to an issue, persuade or influence a particular group of people, or to facilitate future nonviolent action. The message can be directed toward the public, opponents, or people affected by the issue. Methods of protest and persuasion include speeches, public communications, [[petition]]s, symbolic acts, art, processions (marches), and other public assemblies.<ref name="sharp2005" >Gene Sharp, ''Waging Nonviolent Struggle: 20th Century Practice And 21st Century Potential'' (Extending Horizons Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0875581620).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Nonviolent acts of protest and persuasion are symbolic actions performed by a group of people to show their support or disapproval of something. The goal of this kind of action is to bring public awareness to an issue, persuade or influence a particular group of people, or to facilitate future nonviolent action. The message can be directed toward the public, opponents, or people affected by the issue. | ||

===Noncooperation=== | ===Noncooperation=== | ||

| − | + | Noncooperation involves the purposeful withholding of cooperation or the unwillingness to initiate in cooperation with an opponent. The goal of noncooperation is to halt or hinder an industry, political system, or economic process. Methods of noncooperation include labor [[strike]]s, [[boycott|economic boycotts]], [[civil disobedience]], [[Tax resistance|tax refusal]], and general disobedience.<ref name="sharp2005" /> | |

| − | Noncooperation involves the purposeful withholding of cooperation or the unwillingness to initiate in cooperation with an opponent. The goal of noncooperation is to halt or hinder an industry, political system, or economic process. Methods of noncooperation include [[ | ||

===Nonviolent intervention=== | ===Nonviolent intervention=== | ||

| + | Compared with protest and noncooperation, nonviolent intervention is a more direct method of nonviolent action. Nonviolent intervention can be used defensively—for example to maintain an institution or independent initiative—or offensively-for example, to drastically forward a nonviolent struggle into the opponent's territory. Intervention is often more immediate and effective than the other two methods, but is also harder to maintain and more taxing to the participants involved. Tactics must be carefully chosen, taking into account political and cultural circumstances, and form part of a larger plan or strategy. Methods of nonviolent intervention include occupations ([[sit-in]]s), [[blockade]]s, and fasting ([[hunger strikes]]), among others.<ref name="sharp2005" /> | ||

| − | + | Another powerful tactic of nonviolent intervention invokes public scrutiny of the oppressors as a result of the resisters remaining nonviolent in the face of violent repression. If the military or police attempt to repress nonviolent resisters violently, the power to act shifts from the hands of the oppressors to those of the resisters. If the resisters are persistent, the military or police will be forced to accept the fact that they no longer have any power over the resisters. Often, the willingness of the resisters to suffer has a profound effect on the mind and emotions of the oppressor, leaving them unable to commit such a violent act again.<ref name=SharpPolitics>Gene Sharp, ''The Politics of Nonviolent Action'' (P. Sargent Publisher, 1973, ISBN 978-0875580685).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Another powerful tactic of nonviolent intervention invokes public scrutiny of the oppressors as a result of the resisters remaining nonviolent in the face of violent repression. If the military or police attempt to repress nonviolent resisters violently, the power to act shifts from the hands of the oppressors to those of the resisters. If the resisters are persistent, the military or police will be forced to accept the fact that they no longer have any power over the resisters. Often, the willingness of the resisters to suffer has a profound effect on the mind and emotions of the oppressor, leaving them unable to commit such a violent act again.<ref> | ||

==Nonviolent Revolution== | ==Nonviolent Revolution== | ||

| − | + | A '''nonviolent revolution''' is a [[revolution]] using mostly campaigns with [[civil resistance]], including various forms of [[nonviolent resistance|nonviolent protest]], to bring about the departure of governments seen as entrenched and [[authoritarian]]. Such an approach has been advocated by various individuals (such as [[Barbara Deming]], [[Danilo Dolci]], and [[Devere Allen]]) and party groups (for instance, [[Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism]], [[Pacifist Socialist Party]], or [[War Resisters League]]). | |

| − | + | Generally a nonviolent revolution is characterized by simultaneous advocacy of [[democracy]], [[human rights]], and [[national independence]] in the country concerned. One theory of democracy is that its main purpose is to allow peaceful revolutions. The idea is that majorities voting in elections approximate the result of a coup. In 1962, [[John F. Kennedy]] famously said, "Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable."<ref>John F. Kennedy, [https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Address_on_the_First_Anniversary_of_the_Alliance_for_Progress Address on the First Anniversary of the Alliance for Progress] Delivered at The White House, Washington D.C. on March 13, 1962. Retrieved January 9, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The beginnings of the nonviolence movement lie in the [[satyagraha]] philosophy of [[Mahatma Gandhi]], who guided the people of [[British India|India]] to [[independence]] from [[United Kingdom|Britain]]. Despite the violence of the [[Partition of India]] following independence, and numerous revolutionary uprisings which were not under Gandhi's control, India's independence was achieved through legal processes after a period of national [[resistance movement|resistance]] rather than through a military revolution. | |

| − | In | + | In some cases a campaign of civil resistance with a revolutionary purpose may be able to bring about the defeat of a dictatorial regime only if it obtains a degree of support from the armed forces, or at least their benevolent neutrality. In fact, some have argued that a nonviolent revolution would require fraternization with military forces, like in the relatively nonviolent Portuguese [[Carnation Revolution]].<ref>Dan Jakopovich, [http://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article1555 Revolution and the Party in Gramsci's Thought: A Modern Application] ''International Viewpoint'', November 2008. Retrieved January 9, 2020. </ref> |

| − | + | ===Methods and Strategy=== | |

| + | [[Gene Sharp]] has documented and described over 198 different methods of nonviolent action that nonviolent revolutionaries might use in struggle. He argues that no government or institution can rule without the [[consent of the governed]] or oppressed as that is the source of nonviolent power.<ref name=SharpPolitics/> | ||

| − | + | George Lakey laid out a five-stage strategy for nonviolent revolution.<ref>George Lakey, ''Powerful Peacemaking: A Strategy For A Living Revolution'' (New Society Publishers, 1987, ISBN 978-0865710962).</ref> | |

| + | ;Stage 1 – Cultural Preparation or "Conscientization": Education, training and consciousness raising of why there is a need for a nonviolent revolution and how to conduct a nonviolent revolution. | ||

| + | ;Stage 2 – Building Organizations: As training, education and consciousness raising continues, the need to form organizations. Affinity groups or nonviolent revolutionary groups are organized to provide support, maintain nonviolent discipline, organize and train other people into similar affinity groups and networks. | ||

| − | + | ;Stage 3 – Confrontation: Organized and sustained campaigns of picketing, strikes, sit-ins, marches, boycotts, die-ins, blockades to disrupt business as usual in institutions and government. By putting one's body on the line nonviolently the rising movement stops the normal gears of government and business. | |

| − | + | ;Stage 4 – Mass Non Cooperation: Similar affinity groups and networks of affinity groups around the country and world, engage in similar actions to disrupt business as usual. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ;Stage 5 – Developing Parallel Institutions to take over functions and services of government and commerce: In order to create a new society without violence, oppression, environmental destruction, discrimination and one that is environmentally sustainable, nonviolent, democratic, equitable, tolerant, and fair, alternative organizations and structures including businesses must be created to provide the needed services and goods that citizens of a society need. | |

| − | + | ===Examples=== | |

| + | In the 1970s and 1980s, intellectuals in the [[Soviet Union]] and other [[Communist state]]s, and in some other countries, began to focus on [[civil resistance]] as the most promising means of opposing entrenched authoritarian regimes. The use of various forms of unofficial exchange of information, including by [[samizdat]], expanded. Two major revolutions during the 1980s strongly influenced [[political movement]]s that followed. The first was the 1986 [[People Power Revolution]], in the [[Philippines]] from which the term 'people power' came to be widely used, especially in [[Hispanic]] and [[Asia]]n nations.<ref>Hannah Beech, [http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1914872,00.html Corazon Aquino 1933–2009: The Saint of Democracy] ''TIME'', August 17, 2009. Retrieved January 9, 2020. </ref> | ||

| − | + | Three years later, the [[Revolutions of 1989]] that ousted [[communist]] regimes in the [[Eastern Bloc]] reinforced the concept, beginning with the victory of [[Solidarity (Polish trade union)|Solidarity]] in [[1989 Polish legislative elections|that year's Polish legislative elections]]. The Revolutions of 1989 (with the notable exception of the notoriously bloody [[Romanian Revolution of 1989|Romanian Revolution]]) provided the template for the so-called [[color revolution]]s in mainly [[post-communist]] states, which tended to use a [[color]] or [[flower]] as a [[symbol]], somewhat in the manner of the [[Velvet Revolution]] in [[Czechoslovakia]]. | |

| − | + | In December 1989, inspired by the anti-communist revolutions in Eastern Europe, the [[Mongolian Democratic Union]] (MDU) organized popular street protests and hunger strikes [[1990 Democratic Revolution in Mongolia|against the communist regime]]. In 1990, dissidents in the [[Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic]] started civil resistance against the government, but were initially crushed by [[Red Army]] in the [[Black January]] massacre. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Twenty-first century nonviolent revolutions include the Orange Revolution in [[Ukraine]], which took place in the immediate aftermath of the run-off vote of the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, which was claimed to be marred by massive corruption, voter intimidation and electoral fraud. The resulting series of protests and political events included acts of civil disobedience, sit-ins, and general strikes. These nationwide protests succeeded and the results of the original run-off were annulled, with a revote ordered by Ukraine's Supreme Court. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

==Criticism== | ==Criticism== | ||

| − | [[Ernesto Che Guevara]], [[Leon Trotsky]], [[Frantz Fanon]] and [[Subhas Chandra Bose]] were fervent critics of nonviolence, arguing variously that nonviolence and pacifism are an attempt to impose the morals of the [[bourgeoisie]] upon the [[proletariat]], that violence is a necessary accompaniment to revolutionary change or that the right to self-defense is fundamental. | + | [[Ernesto Che Guevara]], [[Leon Trotsky]], [[Frantz Fanon]], and [[Subhas Chandra Bose]] were fervent critics of nonviolence, arguing variously that nonviolence and pacifism are an attempt to impose the morals of the [[bourgeoisie]] upon the [[proletariat]], that violence is a necessary accompaniment to revolutionary change, or that the right to [[self-defense]] is fundamental. [[Malcolm X]] clashed with civil rights leaders over the issue of nonviolence, arguing that violence should not be ruled out if no option remained: "I believe it's a crime for anyone being brutalized to continue to accept that brutality without doing something to defend himself."<ref>Malcolm X and Alex Haley, ''The Autobiography of Malcolm X'' (Ballantine Books, 1992, ISBN 978-9990065169). </ref> |

| − | [[George | + | In the midst of repression of radical [[African American]] groups in the United States during the 1960s, [[Black Panther Party|Black Panther]] member [[George Jackson (Black Panther)|George Jackson]] said of the nonviolent tactics of [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]]: |

| + | <blockquote>The concept of nonviolence is a false ideal. It presupposes the existence of compassion and a sense of justice on the part of one's adversary. When this adversary has everything to lose and nothing to gain by exercising justice and compassion, his reaction can only be negative.<ref>George Jackson, ''Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson'' (Lawrence Hill Books, 1994, ISBN 978-1556522307).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[George Orwell]] argued that the nonviolent resistance strategy of Gandhi could be effective in countries with "a free press and the right of assembly," which make it possible "not merely to appeal to outside opinion, but to bring a mass movement into being, or even to make your intentions known to your adversary." However, he was skeptical of Gandhi's approach being effective in the opposite sort of circumstances.<ref>George Orwell, [https://www.orwell.ru/library/reviews/gandhi/english/e_gandhi.html Reflections on Gandhi] Retrieved January 9, 2020.</ref> |

| − | + | [[Reinhold Niebuhr]] similarly affirmed Gandhi's approach while criticizing certain aspects: "The advantage of non-violence as a method of expressing moral goodwill lies in the fact that it protects the agent against the resentments which violent conflict always creates in both parties to a conflict, and that it proves this freedom of resentment and ill-will to the contending party in the dispute by enduring more suffering than it causes."<ref>Reinhold Niebuhr, ''Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics'' (Wipf & Stock Pub, 2010, ISBN 978-1608998012).</ref> However, Niebuhr also noted that "The differences between violent and non-violent methods of coercion and resistance are not so absolute that it would be possible to regard violence as a morally impossible instrument of social change."<ref>Larry Rasmussen (ed.), ''Reinhold Niebuhr: Theologian of Public Life'' (Fortress Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0800634070).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Anarchist]] [[Peter Gelderloos]] has criticized nonviolence as being ineffective, racist, statist, patriarchal, tactically and strategically inferior to militant activism, and deluded.<ref name="Gelderloos">Peter Gelderloos, ''How Nonviolence Protects the State'' (Detritus Books, 2018, ISBN 978-1909798571).</ref> He claims that traditional histories whitewash the impact of nonviolence, ignoring the involvement of militants in such movements as the [[Indian independence movement]] and the [[Civil Rights Movement]] and falsely showing Gandhi and King as being their respective movement's most successful activists. He further argues that nonviolence is generally advocated by privileged white people who expect "oppressed people, many of whom are people of color, to suffer patiently under an inconceivably greater violence, until such time as the Great White Father is swayed by the movement's demands or the pacifists achieve that legendary 'critical mass.'"<ref name="Gelderloos"/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | *Ackerman, Peter, and Jack DuVall. ''A Force More Powerful: A Century of Non-violent Conflict''. St. Martin's Griffin, 2000. ISBN 978-0312240509 | ||

| + | *Bartholomeusz, Tessa J. ''In Defense of Dharma''. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0700716821 | ||

| + | *Batchelor, Martine. ''The Spirit of the Buddha''. Yale University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0300164077 | ||

| + | *Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.). ''The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya''. Wisdom Publications, 2003. ISBN 978-0861713318 | ||

| + | *Chapple, Christopher. ''Non-violence to Animals, Earth and Self in Asian Traditions''. Sri Satguru Publications, 1995. ISBN 978-8170304265 | ||

| + | *Dundas, Paul. ''The Jains''. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0415266062 | ||

| + | *Dyke, Harvey L. (ed.). ''The Pacifist Impulse in Historical Perspective''. University of Toronto Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0802007773 | ||

| + | *Eppert, Claudia, and Hongyu Wang (eds.). ''Cross-Cultural Studies in Curriculum: Eastern Thought, Educational Insights''. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-1843153665 | ||

| + | *Fischer, Louis. ''Gandhi: His Life and Message to the World''. Signet, 2010. ISBN 978-0451531704 | ||

| + | *Flugel, Peter (ed.). ''Studies in Jaina History and Culture''. Routledge, 2006. ISBN 978-0415360999 | ||

| + | *Gandhi, Mohandas K. ''Hind Swaraj Or Indian Home Rule''. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2009. ISBN 978-1449922214 | ||

| + | *Gelderloos, Peter. ''How Nonviolence Protects the State''. Detritus Books, 2018. ISBN 978-1909798571 | ||

| + | *Harvey, Peter (ed.). ''Buddhism''. Bloomsbury Academic, 2001. ISBN 978-0826453518 | ||

| + | *Harvey, Peter. ''An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices''. Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 0521676746 | ||

| + | *Jackson, George. ''Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson''. Lawrence Hill Books, 1994. ISBN 978-1556522307 | ||

| + | *Jain, Vijay K. ''Acharya Amritchandra's Purusartha Siddhi Upaya''. Vikalp Printers, 2012. ISBN 978-8190363945 | ||

| + | *Jha, D.N. ''The Myth of the Holy Cow''. Verso, 2004. ISBN 978-1859844243 | ||

| + | *Johansson, Rune E.A. ''The Dynamic Psychology of Early Buddhism''. Curzon Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0700701148 | ||

| + | *King, Martin Luther Jr. ''Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story''. Beacon Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0807000694 | ||

| + | *Kool, V.K. (ed.). ''Perspectives on Nonviolence''. Springer New York, 2011. ISBN 978-1461287834 | ||

| + | *Kurlansky, Mark. ''Nonviolence: The History of a Dangerous Idea''. Modern Library, 2008. ISBN 978-0812974478 | ||

| + | *Kurtz, Lester R. (ed.). ''Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, and Conflict''. Academic Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0123695031 | ||

| + | *Lakey, George. ''Powerful Peacemaking: A Strategy For A Living Revolution''. New Society Publishers, 1987. ISBN 978-0865710962 | ||

| + | *Niebuhr, Reinhold. ''Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics''. Wipf & Stock Pub, 2010. ISBN 978-1608998012 | ||

| + | *Pandey, Janardan (ed.). ''Gandhi and 21st Century''. Concept Publishing Company, 1998. ISBN 978-8170226727 | ||

| + | *Patel, Haresh. ''Thoughts from the Cosmic Field in the Life of a Thinking Insect [A Latter-Day Saint]''. Eloquent Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1606938461 | ||

| + | *Pope, G.U. ''Tirukkural: English Translation and Commentary''. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017. ISBN 978-1975616724 | ||

| + | *Preece, Rod. ''Animals and Nature: Cultural Myths, Cultural Realities''. University of British Columbia Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0774807241 | ||

| + | *Rasmussen, Larry (ed.). ''Reinhold Niebuhr: Theologian of Public Life''. Fortress Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0800634070 | ||

| + | *Roberts, Adam, and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.). ''Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present''. Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0199691456 | ||

| + | *Robinson, Paul F. (ed.). ''Just War in Comparative Perspective''. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 978-0754635871 | ||

| + | *Saddhatissa, Hammalawa. ''Buddhist Ethics''. Wisdom Publications, 1997. ISBN 978-0861711246 | ||

| + | *Sharp, Gene. ''The Politics of Nonviolent Action''. P. Sargent Publisher, 1973. ISBN 978-0875580685 | ||

| + | *Sharp, Gene. ''Waging Nonviolent Struggle: 20th Century Practice And 21st Century Potential''. Extending Horizons Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0875581620 | ||

*Sharp, Gene. ''Sharp's Dictionary of Power and Struggle: Language of Civil Resistance in Conflicts''. Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0199829880 | *Sharp, Gene. ''Sharp's Dictionary of Power and Struggle: Language of Civil Resistance in Conflicts''. Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0199829880 | ||

| − | + | *Sundararajan, K.R., and Bithika Mukerji (eds.). ''Hindu Spirituality: Postclassical and Modern''. Herder & Herder, 1997. ISBN 978-0824516710 | |

| − | * | + | *Walters, Kerry S., and Lisa Portmess (eds.). ''Religious Vegetarianism: From Hesiod to the Dalai Lama''. SUNY Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0791449721 |

| − | + | *Walli, Koshelya. ''The Conception of Ahimsa in Indian Thought''. Bharata Manisha, 1974. | |

| − | + | *Walter, Nicolas, David Goodway (ed.). ''Damned Fools in Utopia and Other Writings on Anarchism and War Resistance''. PM Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1604862225 | |

| − | + | *X, Malcolm, and Alex Haley. ''The Autobiography of Malcolm X''. Ballantine Books, 1992. ISBN 978-9990065169 | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 15, 2022. | |

* [https://www.crmvet.org/info/nv2.htm Two Kinds of Nonviolent Resistance] Bruce Hartford, 2004 | * [https://www.crmvet.org/info/nv2.htm Two Kinds of Nonviolent Resistance] Bruce Hartford, 2004 | ||

| − | + | * ''[https://www.howtostartarevolution.org/ How to Start a Revolution]'', documentary film directed by Ruaridh Arrow | |

| − | * ''[https://www.howtostartarevolution.org/ How to Start a Revolution]'', documentary directed by | + | *[http://www.crmvet.org//info/nvrrr.htm Nonviolent Resistance, Reform, & Revolution] Bruce Hartford, 2008 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.crmvet.org//info/nvrrr.htm Nonviolent Resistance, Reform, & Revolution] | ||

| − | |||

[[Category:Social sciences]] | [[Category:Social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Sociology]] | [[Category:Sociology]] | ||

{{Credits|Nonviolence|927403611|Nonviolent_resistance|928035752|Nonviolent_revolution|930517118}} | {{Credits|Nonviolence|927403611|Nonviolent_resistance|928035752|Nonviolent_revolution|930517118}} | ||

Latest revision as of 02:40, 16 November 2022

Nonviolence is the practice of being harmless to self and others under every condition. It comes from the belief that hurting people, animals, or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and refers to a general philosophy of abstention from violence. This may be based on moral, religious, or spiritual principles, or it may be for purely strategic or pragmatic reasons.

Forms of nonviolence draw inspiration from both religious or ethical beliefs and political analysis. Religious or ethically based nonviolence is sometimes referred to as principled, philosophical, or ethical nonviolence, while nonviolence based on political analysis is often referred to as tactical, strategic, or pragmatic nonviolent action. Both of these dimensions may be present within the thinking of particular movements or individuals.

Nonviolence also has "active" or "activist" elements, in that believers generally accept the need for nonviolence as a means to achieve political and social change. Thus, for example, the nonviolence of Tolstoy and Gandhi is a philosophy and strategy for social change that rejects the use of violence, but at the same time sees nonviolent action (also called civil resistance) as an alternative to passive acceptance of oppression or armed struggle against it. In general, advocates of an activist philosophy of nonviolence use diverse methods in their campaigns for social change, including critical forms of education and persuasion, mass noncooperation, civil disobedience, nonviolent direct action, and social, political, cultural, and economic forms of intervention.

History

Nonviolence or Ahimsa is one of the cardinal virtues[1] and an important tenet of Jainism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. It is a multidimensional concept, inspired by the premise that all living beings have the spark of the divine spiritual energy.[2] Therefore, to hurt another being is to hurt oneself. It has also been related to the notion that any violence has karmic consequences.

While ancient scholars of Hinduism pioneered and over time perfected the principles of Ahimsa, the concept reached an extraordinary status in the ethical philosophy of Jainism.[1][3] According to Jain mythology, the first tirthankara, Rushabhdev, originated the idea of nonviolence over a million years ago.[4] Historically, Parsvanatha, the twenty-third tirthankara of Jainism, advocated for and preached the concept of nonviolence in around the eighth century B.C.E. Mahavira, the twenty-fourth and last tirthankara, then further strengthened the idea in the sixth century B.C.E.

The idea of using nonviolent methods to achieve social and political change has been expressed in Western society over the past several hundred years: Étienne de La Boétie's Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (sixteenth century) and P.B. Shelley's The Masque of Anarchy (1819) contain arguments for resisting tyranny without using violence, while in 1838, William Lloyd Garrison helped found the New England Non-Resistance Society, a society devoted to achieving racial and gender equality through the rejection of all violent actions.[5]

In modern times, nonviolent methods of action have become a powerful tool for social protest and revolutionary social and political change.[1][6] For example, Mahatma Gandhi led a successful decades-long nonviolent struggle against British rule in India. Martin Luther King and James Bevel adopted Gandhi's nonviolent methods in their campaigns to win civil rights for African Americans. César Chávez led campaigns of nonviolence in the 1960s to protest the treatment of farm workers in California. The 1989 "Velvet Revolution" in Czechoslovakia that saw the overthrow of the Communist government is considered one of the most important of the largely nonviolent Revolutions of 1989.

Nonviolence has obtained a level of institutional recognition and endorsement at the global level. On November 10, 1998, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the first decade of the twenty-first century and the third millennium, the years 2001 to 2010, as the International Decade for the Promotion of a Culture of Peace and Non-Violence for the Children of the World].[7]

Ethical nonviolence

For many, practicing nonviolence goes deeper than abstaining from violent behavior or words. It means overriding the impulse to be hateful and holding love for everyone, even those with whom one strongly disagrees. In this view, because violence is learned, it is necessary to unlearn violence by practicing love and compassion at every possible opportunity. For some, the commitment to nonviolence entails a belief in restorative or transformative justice and the abolition of the death penalty and other harsh punishments. This may involve the necessity of caring for those who are violent.

Nonviolence, for many, involves a respect and reverence for all sentient, and perhaps even non-sentient, beings. This might include the belief that all sentient beings share the basic right not to be treated as the property of others, the practice of not eating animal products or by-products (vegetarianism or veganism), spiritual practices of non-harm to all beings, and caring for the rights of all beings. Mohandas Gandhi, James Bevel, and other nonviolent proponents advocated vegetarianism as part of their nonviolent philosophy. Buddhists extend this respect for life to animals and plants, while Jains extend it to animals, plants, and even small organisms such as insects.

Religious nonviolence

Ahimsa is a Sanskrit term meaning "nonviolence" or "non-injury" (literally: the avoidance of himsa: violence). The principle of ahimsa is central to the religions of Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, being a key precept in their ethical codes.[8] It implies the total avoidance of harming of any kind of living creatures not only by deeds, but also by words and in thoughts.

Hinduism

The Hindu scriptures contain mixed messages on the necessity and scope of nonviolence in human affairs. Some texts insist that ahimsa is the highest duty, while other texts make exceptions in the cases of war, hunting, ruling, law enforcement, and capital punishment.

Ahimsa as an ethical concept evolved in the Vedic texts.[3][9] The oldest scripts, along with discussing ritual animal sacrifices, indirectly mention ahimsa, but do not emphasize it. Over time, the concept of ahimsa was increasingly refined and emphasized, ultimately becoming the highest virtue by the late Vedic era (about 500 B.C.E.).

The Mahabharata, one of the epics of Hinduism, has multiple mentions of the phrase Ahimsa Paramo Dharma (अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मः), which literally means: nonviolence is the highest moral virtue. For example, Mahaprasthanika Parva has the following verse emphasizes the cardinal importance of Ahimsa in Hinduism:[10]

- अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मस तथाहिंसा परॊ दमः।

- अहिंसा परमं दानम अहिंसा परमस तपः।

- अहिंसा परमॊ यज्ञस तथाहिस्मा परं बलम।

- अहिंसा परमं मित्रम अहिंसा परमं सुखम।

- अहिंसा परमं सत्यम अहिंसा परमं शरुतम॥

The literal translation is as follows:

- Ahimsa is the highest virtue, Ahimsa is the highest self-control,

- Ahimsa is the greatest gift, Ahimsa is the best suffering,

- Ahimsa is the highest sacrifice, Ahimsa is the finest strength,

- Ahimsa is the greatest friend, Ahimsa is the greatest happiness,

- Ahimsa is the highest truth, and Ahimsa is the greatest teaching.[11]

Some other examples where the phrase Ahimsa Paramo Dharma are discussed include Adi Parva, Vana Parva, and Anushasana Parva. The Bhagavad Gita discusses the doubts and questions about appropriate response when one faces systematic violence or war. These verses develop the concepts of lawful violence in self-defense and the theories of just war. However, there is no consensus on this interpretation. Gandhi, for example, considered this debate about nonviolence and lawful violence as a mere metaphor for the internal war within each human being, when he or she faces moral questions.[12]

Self-defense, criminal law, and war

The classical texts of Hinduism devote numerous chapters to discussion of what people who practice the virtue of Ahimsa can and must do when they are faced with war, violent threat, or need to sentence someone convicted of a crime. These discussions have led to theories of just war, theories of reasonable self-defense, and theories of proportionate punishment.[13] Arthashastra discusses, among other things, why and what constitutes proportionate response and punishment.[14]

- War

The precepts of Ahimsa in Hinduism require that war must be avoided if at all possible, with sincere and truthful dialogue. Force must be the last resort. If war becomes necessary, its cause must be just, its purpose virtuous, its objective to restrain the wicked, its aim peace, its method lawful.[14] War can only be started and stopped by a legitimate authority. Weapons used must be proportionate to the opponent and the aim of war, not indiscriminate tools of destruction. All strategies and weapons used in the war must be to defeat the opponent, not designed to cause misery to them; for example, use of arrows is allowed, but use of arrows smeared with painful poison is not allowed. Warriors must use judgment in the battlefield. Cruelty to the opponent during war is forbidden. Wounded, unarmed opponent warriors must not be attacked or killed, they must be brought to safety and given medical treatment.[14] Children, women and civilians must not be injured. While the war is in progress, sincere dialogue for peace must continue.[13]

- Self-defense

In matters of self-defense, different interpretations of ancient Hindu texts have been offered, such as that self-defense is appropriate, criminals are not protected by the rule of Ahimsa, and Hindu scriptures support the use of violence against an armed attacker.[15][16] Ahimsa does not imply pacifism.[15]

Inspired by Ahimsa, principles of self-defense have been developed in the martial arts. Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido, described his inspiration as ahimsa.[17]

- Criminal law

Some have concluded that Hindus have no misgivings about the death penalty. Their position is that evil-doers who deserve death should be killed, and that a king in particular is obliged to punish criminals and should not hesitate to kill them, even if they happen to be his own brothers and sons.[15]

Other scholars have concluded that the scriptures of Hinduism suggest sentences for any crime must be fair, proportionate, and not cruel.[13][14]

Non-human life

Across the texts of Hinduism, there is a profusion of ideas about the virtue of ahimsa when applied to non-human life, but without universal consensus.

This precept is not found in the oldest verses of Vedas, but increasingly becomes one of the central ideas between 500 B.C.E. and 400 C.E.[3] In the oldest texts, numerous ritual sacrifices of animals, including cows and horses, are highlighted and hardly any mention is made of ahimsa in relation to non-human life.[18] However, the ancient Hindu texts discourage wanton destruction of nature, including wild and cultivated plants. Hermits (sannyasins) were urged to live on a fruitarian diet so as to avoid the destruction of plants.[19]

Hindu scriptures dated to between the fifth century and first century B.C.E., in discussing human diet, initially suggest kosher meat may be eaten, suggesting that only meat obtained through ritual sacrifice can be eaten. This evolved into the belief that one should eat no meat because it hurts animals, with verses describing the noble life as one that lives on flowers, roots, and fruits alone.[3]

Later Hindu texts declare Ahimsa one of the primary virtues, and that killing or harming any life to be against dharma (moral life). Finally, the discussion in the Upanishads and the Hindu epics shifts to whether a human being can ever live his or her life without harming animal and plant life in some way; which and when plants or animal meat may be eaten, whether violence against animals causes human beings to become less compassionate, and if and how one may exert least harm to non-human life consistent with ahimsa, given the constraints of life and human needs.

Many of the arguments proposed in favor of nonviolence to animals refer to the bliss one feels, the rewards it entails before or after death, the danger and harm it prevents, as well as to the karmic consequences of violence.[15] For example, Tirukkuṛaḷ, written between 200 B.C.E. and 400 C.E., says that Ahimsa applies to all life forms. It dedicates several chapters to the virtue of ahimsa, namely, moral vegetarianism, non-harming, and non-killing, respectively.[20]

Jainism

In Jainism, the understanding and implementation of Ahimsā is more radical, scrupulous, and comprehensive than in any other religion. The statement ahimsā paramo dharmaḥ is often found inscribed on the walls of the Jain temples.[21][22] Killing any living being out of passion is considered hiṃsā (to injure) and abstaining from such an act is ahimsā (noninjury).[23] Like in Hinduism, the aim is to prevent the accumulation of harmful karma.

Mahatma Gandhi expressed the view:

No religion in the world has explained the principle of Ahimsa so deeply and systematically as is discussed with its applicability in every human life in Jainism. As and when the benevolent principle of Ahimsa or non-violence will be ascribed for practice by the people of the world to achieve their end of life in this world and beyond. Jainism is sure to have the uppermost status and Lord Mahavira is sure to be respected as the greatest authority on Ahimsa.[24]

The vow of ahimsā is considered the foremost among the five vows of Jainism. Other vows like truth (Satya) are meant for safeguarding the vow of ahimsā.[23] In the practice of Ahimsa, the requirements are less strict for the lay persons (sravakas) who have undertaken anuvrata (Smaller Vows) than for the Jain monastics who are bound by the Mahavrata "Great Vows."[25]

The Jain concept of Ahimsa is characterized by several aspects. Theoretically, all life forms are said to deserve full protection from all kinds of injury, but Jains recognize a hierarchy of life. Mobile beings are given higher protection than immobile ones. Among mobile beings, they distinguish between one-sensed, two-sensed, three-sensed, four-sensed, and five-sensed ones; a one-sensed animal having touch as its only sensory modality. The more senses a being has, the more care they receive.

Jains do not make any exception for ritual sacrifice and professional warrior-hunters. Killing of animals for food is absolutely ruled out.[15] Jains also make considerable efforts not to injure plants in everyday life as far as possible. Though they admit that plants must be destroyed for the sake of food, they accept such violence only inasmuch as it is indispensable for human survival, and there are special instructions for preventing unnecessary violence against plants. Jains go out of their way so as not to hurt even small insects and other minuscule animals. Some Jains abstain from farming because it inevitably entails unintentional killing or injuring of many small animals, such as worms and insects, but agriculture is not forbidden in general and there are Jain farmers.[21]

Buddhism

The traditional Buddhist understanding of nonviolence is not as rigid as the Jain one. In Buddhist texts Ahimsa (or its Pāli cognate avihiṃsā) is part of the Five Precepts (Pañcasīla), the first of which is to abstain from killing. This precept of Ahimsa is applicable to both the Buddhist layperson and the monk community.[26]

The Ahimsa precept is not a commandment and transgressions did not invite religious sanctions for laypersons, but its power is in the Buddhist belief in karmic consequences and their impact in the afterlife during rebirth.[27] Killing, in Buddhist belief, could lead to rebirth in the hellish realm, and for a longer time in more severe conditions if the murder victim was a monk.[27] Saving animals from slaughter for meat is believed to be a way to acquire merit for better rebirth. These moral precepts have been voluntarily self-enforced in lay Buddhist culture through the associated belief in karma and rebirth.[27] The Buddhist texts not only recommend Ahimsa, but suggest avoiding trading goods that contribute to or are a result of violence:

These five trades, O monks, should not be taken up by a lay follower: trading with weapons, trading in living beings, trading in meat, trading in intoxicants, trading in poison.[28]

Unlike lay Buddhists, transgressions by monks do invite sanctions. Full expulsion of a monk from sangha follows instances of killing, just like any other serious offense against the monastic nikaya code of conduct.[27]

War

Violent ways of punishing criminals and prisoners of war are not explicitly condemned in Buddhism, but peaceful ways of conflict resolution and punishment with the least amount of injury are encouraged.[29]